Abstract

Background

A large proportion of all emergency department (ED) visits in the U.S. are for non-urgent conditions. Use of the ED for non-urgent conditions may lead to excessive healthcare spending, unnecessary testing and treatment, and weaker patient-primary care provider relationships.

Objectives

To understand the factors influencing an individual’s decision to visit an ED for a non-urgent condition

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature review of the U.S. literature. Multiple databases were searched for studies published after 1990, conducted in the U.S., and which assessed factors associated with non-urgent ED use. Based on those results we developed a conceptual framework.

Results

Twenty-six articles met inclusion criteria. No two articles used the same exact definition of non-urgent visits. Across the relevant articles, the average fraction of all ED visits that were judged to be non-urgent (whether prospectively at triage or retrospectively following ED evaluation) was 37% (range: 8–62%). Articles were very heterogeneous with respect to study design, population, comparison, group, and non-urgent definition. The limited evidence suggests that younger age, convenience of the ED compared to alternatives, referral to the ED by a physician, and negative perceptions about alternatives such as primary care providers all play a role in driving nonurgent ED use.

Conclusion

Our structured overview of the literature and conceptual framework can help to inform future research and the development of evidence-based interventions to reduce non-urgent ED use.

INTRODUCTION

Background

Non-urgent Emergency Department (ED) visits are typically defined as visits for conditions for which a delay of several hours would not increase the likelihood of an adverse outcome.1,2 Most studies find that at least 30% of all ED visits in the US are non-urgent, although select studies such as those using National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Survey data report lower percentages (<10%).3–8 Visiting the ED instead of another care site (e.g. physician’s office, retail clinic, urgent care) for a non-urgent condition may lead to excessive healthcare spending, unnecessary testing and treatment, and represent a missed opportunity to promote longitudinal relationships with primary care physicians.4–6,9–12 A recent study projected $4.4 billion in annual savings if non-urgent ED visits were cared for in retail clinics or urgent care centers during the hours these facilities are open.13 With increasing demand and a shortage of primary care providers, non-urgent ED use will likely increase in the near future. Recent predictions suggest that implementation of the Affordable Care Act and resulting expansions of insurance coverage will contribute to even higher levels of ED usage.14,15

There is widespread interest in interventions to discourage non-urgent ED visits. A 2006 survey found that 30% of emergency physicians work in hospitals that have implemented practices to discourage non-urgent visits.16 Interventions by health systems and payers have included patient education on what is appropriate ED use, financial disincentives such as higher-copayments for ED visits, and encouraging primary care physicians (PCPs) to provide care in the evenings and weekends.17–19 Despite these efforts, non-urgent ED visits have continued to rise.20 One explanation could be that prior interventions have not adequately addressed the underlying issues that lead patients to visit EDs for non-urgent conditions.21 Moreover, policies to deter ED use can have negative, unintended consequences. For example, enrollees in high-deductible health plans, who bear a higher share of the costs of an ED visit, are less likely to seek care for a true emergency.22 Non-urgent ED use has been discussed in the peer-reviewed literature for the last three decades;23 however, no systematic review of non-urgent ED use in the U.S. has been published to date.

We conducted a systematic review of the literature and developed a conceptual framework to understand why individuals visit the ED for non-urgent conditions. Our goal was to highlight gaps in knowledge, inform future research on this topic, and empirically inform future interventions that attempt to decrease the number of non-urgent ED visits.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a systematic review of the peer-reviewed and grey literature to identify factors associated with non-urgent ED use by adults in the U.S. Studies outside the US were excluded because they may not generalize to the unique features of the U.S. healthcare system.24 A health sciences research librarian worked with the study team to develop our search strategy. We searched multiple databases including: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), OAISTER, ISI Web of Science, New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature Database, PsychInfo, and PubMed. Searches used the following free text and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms: ("Emergency Service, Hospital" OR "emergency room" OR "emergency department") AND ("nonurgent" OR "non-urgent" OR "unnecessary" OR “inappropriate”). We also used the “related citations” function in PubMed to identify any articles determined to be similar to articles selected for inclusion, and we hand-searched the reference lists of all included articles. The search for abstracts was conducted in January 2011.

Data Processing

Two reviewers (L.U.P. and E.G.) independently examined each abstract returned by the PubMed search, and one reviewer (L.U.P) reviewed the abstracts returned by the other search engines (less than 10% of the total abstracts reviewed). If either or both reviewers determined that an abstract met inclusion criteria, it underwent a more thorough full-text review. One reviewer (L.U.P) evaluated the full-text articles on whether they met inclusion criteria and extracted data on all included articles. To meet inclusion criteria, articles had to be published after January 1990, be written in English, and present some quantitative data (including descriptive data) on non-urgent ED use. We excluded dissertations, articles without abstracts, and articles exclusively focused on pediatric or non-U.S. populations. Articles that presented qualitative data only or reviewed existing literature were not formally included in the review, but were used to inform the creation of a conceptual framework.24–35

To facilitate data extraction, we created a standardized data form to collect information from included articles. Information gathered, as available, included: study population, sample size, setting, design, comparison group, response rate, definition of a non-urgent visit, independent and dependent variables, key findings, and use of a conceptual framework. A variety of terms were used to describe non-urgent visits including “inappropriate visits,”36 “avoidable visits,”16 “nonemergency visits,”37 and “minor illness visits.”38 In this article we chose the most prevalent term, “non-urgent visits”. The research team elected not to rate the quality of articles because all the studies were observational in nature and the majority did not use multivariate statistics.

RESULTS

Identification of Relevant Articles

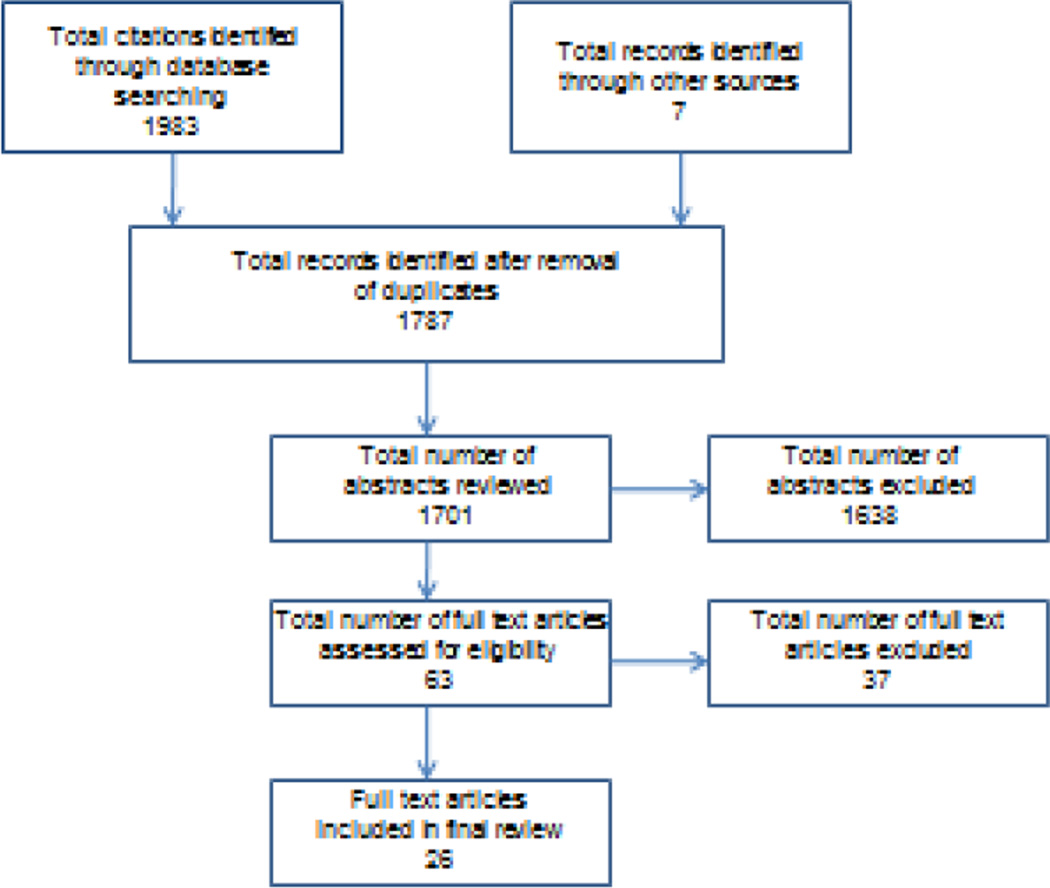

The initial search strategy generated 1,983 abstracts. An additional seven abstracts were obtained by hand-searching the reference lists of full text articles and using the “related citations” feature in Pubmed. From this list, the reviewers identified 63 articles for full text review, of which 26 satisfied criteria for inclusion (Figure 1). The primary reasons for exclusion included lack of quantitative data and an exclusive focus on non-U.S. patients.

Figure 1.

Study Selection Flow Diagram

Overview of Articles and Definition of Non-Urgent

Six studies (23%) described only visits for non-urgent conditions (Table 1). Of those, four articles (16%) described non-urgent visits to the ED and two articles (8%) compared non-urgent ED visits to PCP visits for similar conditions.37,39 The other 20 articles (77%) compared nonurgent ED visits to other types of ED visits, including urgent visits, urgent and emergent visits,40,41 and all ED visits.16,38 (Table 2)

Table 1.

Design Features and Results of Studies of Non-Urgent Visits (n=6)

| Reference | Study Design | Non-urgent Definition | Sample Description and Setting | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brim (2008)41 | Cross-sectional survey | Determined prospectively at triage (based on vital signs and expectations of procedures and treatments) | Convenience sample of adults presenting during business hours to one ED in Washington State | 64 ED patients |

| Butler (1998)36 | Cross-sectional survey and review of health plan administrative data | Determined retrospectively from review of medical record (based on diagnosis). Also used alternate definitions from the literature to test the sensitivity of the logistic regression model | Enrollees of one Medicaid HMO in Colorado who had a non-urgent visit to an ED or PCP | 581 patients with 1943 visits (outcome of interest was whether a particular nonemergency visit was to the ED or primary care provider) |

| Gill (1996)52 | Cross-sectional survey and medical records review | Determined prospectively at triage (based on ability to wait several hours or more for an evaluation) | Convenience sample in one ED in an unspecified location | 268 ED patients |

| Northington (2005)53 | Cross-sectional survey | Determined prospectively at triage (based on vital signs, responsiveness, level of distress, and expectations of testing) | Convenience sample of adult self-referred patients in one ED in North Carolina | 279 ED patients |

| Redstone (2008)54 | Cross-sectional survey | Determined prospectively at triage (based on symptoms, vital signs and expectations of resource use) | Convenience sample of adults with an established primary care provider presenting with a non-urgent condition to one ED in Colorado. | 240 ED patients |

| Schwartz (1995)38 | Cross-sectional survey | Not clearly defined: Patients with conditions that were not life threatening such as flu, cold, or sprains | Patients who had a non-urgent visit to either one ED in Georgia or to a family practice clinic (FPC) | 52 ED patients and 42 FPC patients |

Table 2.

Design Features of Studies Comparing Non-Urgent ED visits to Other ED visits (n=20)

| Reference | Study Design | Non-urgent Definition | % Non-urgent | Sample Description and Setting | Sample Size | Covariates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker (1995)55 | Cross-sectional survey and chart review | Determined prospectively by physician rating at triage (based on whether patients needed to be seen within 24 hours) | 43% | Adult ambulatory ED patients in a Los Angeles public hospital | 1190 | None-Descriptive statistics only |

| Bond (1999)58 | Retrospective chart review | Determined prospectively by nurse at triage (based on whether patient required a physician assessment in under two hours) | 62% | Northern Virginia ED patients with seven or more visits within 12 months | 122 patients with 1,185 visits | None-Bivariate only |

| Campbelll (1998)35 | Retrospective medical record review | Determined retrospectively by medical record review (based on vital signs, admission to the hospital, chief complaint, presence of acute exacerbation of chronic condition, timing of visit) | 37% | ED patients with a PCP seen on weekends or evenings | 332 | None-Bivariate only |

| Coleman (2002)57 | Cross sectional survey and review of health plan administrative data | Determined retrospectively by medical record review. Compared four distinct definitions based on 1) Diagnosis at discharge 2) Whether patient was admitted to the hospital 3) Whether the patient walked to the ED 4)Whether the patient presented during clinic hours | 1) 38% 2) 55% 3) 43% 4) 38% |

Patients enrolled in a Colorado HMO outpatient care management program. Program included older patients with multiple chronic illnesses, high utilization history or PCP referral. | 104 | Age, gender, chronic conditions, co-morbidity, functional status, caregiver support, use of skilled home health nursing services, prior ED use |

| Cunningham (1995)22 | Cross-sectional survey | Determined retrospectively by patient self-report (based on whether visit resulted in admission, whether the visit was associated with an accident or injury, whether a surgical procedure was performed, whether the patient was referred to the ED, whether the patient arrived by ambulance, and whether the patient reported their condition to be very serious) | 40% | Adults across the U.S who participated in the National Medical Expenditure Survey | 14,000 households with 9,461 household-reported ED visits | Health status, insurance coverage, demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status, number of physicians and EDs in county of residence, per capita income |

| Davis (2010)43 | Retrospective review of administrative and claims data | Determine d retrospectively based on administrative and claims data (based on procedure ordered and ICD-9 codes) | 24% of visits by Medicaid patients and 16% of visits by non-Medicaid patients | Members of the largest insurer in Hawaii who had an ED visit that did not result in a hospitalization | 650,000 enrollees | Age, gender, chronic diseases, and having a weekend or weekday visit |

| Doty (2005)48 | Cross-sectional survey | Determined retrospectively by patient self-report (based on whether patient reported that the condition could have been treated by a regular physician if one had been available) | 23% | Adults across the U.S. (ages 19–64) who responded to the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey | 4,350 adults | Poverty status and insurance coverage |

| Garcia (2010)50 | Retrospective review of medical records | Determined retrospectively based on medical record review (based on whether patient should be seen within 2–24 hours) | 10% | National sample of ED visits by persons under 64 years of age (National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey) | Not described | None-Bivariate only |

| Harris Interactive (2005)15 | Cross-sectional survey | Determined retrospectively by patient self-report (based on whether visit occurred during business hours and could have been treated by a PCP or could have waited 24 hours for care) | 21% | General public (oversample of recent ED users) | 1000 patients who used the ED in the last year | None-Bivariate only |

| Gooding (1996)51 | Retrospective review of medical records | Determined retrospectively by medical record review (based on medical provider classification patient record form and whether non-routine diagnostic procedure were performed | 19% (with another 40% potentially non-urgent) | National sample of ED visits by persons under 65 years of age (National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey) | 25,509 ED patient records | Age, sex, race, ethnicity, region, urban location, hospital ownership |

| Han (2003)47 | Cross-sectional survey and retrospective review of medical records | Determined retrospectively from medical record review (based on complaint, presence of high risk condition, vital signs, and hospitalization) | 73% of patients had at least one non-urgent visit in a six month time frame | Homeless adults attending soup kitchens in 8 U.S. cities | 241 adults with 688 ED records | Age, gender, race, marital status, and education |

| Liu (1999)42 | Retrospective review of medical records | Determined retrospectively from medical record review (based on whether the patient requires medical attention immediately or within a few hours) | 54% | National sample of ED visits by adults (National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey) | 135, 723 ED patient records | Disease category, age, sex, race, region, MSA, hospital ownership, insurance |

| Maclean (1999)40 | Retrospective review of medical records | Determined prospectively at triage (definition not precisely defined) | 52% | Random sample of patients presenting to 89 hospital EDs in 35 states | 7,934 | None-Descriptive statistics only |

| Niska (2010)2 | Retrospective review of medical records | Determined prospectively at triage (definition not precisely defined) | 8% | National sample of ED visits by adults (National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey) | 35,490 ED patient records | None-Descriptive statistics only |

| Petersen (1998)44 | Cross sectional survey | Determined prospectively at triage (based on vital signs, history, age, symptoms, and duration of symptoms) | 50% | Adult patients who presented to one of five urban teaching hospitals in the Northeast with the chief complaint of abdominal pain, chest pain, or asthma | 1696 | Age, sex, race, insurance, education, marital status, employment, English speaking, regular physician, comorbidities, health status |

| Rubin (1995)49 | Cross-sectional survey and chart review | Determined prospectively at triage (based on referral, symptoms, complaint, and vital signs) | 37% | Patients presenting to one urban ED | 507 | None-Bivariate only |

| Sarver (2002)46 | Cross-sectional survey and medical record review | Determined retrospectively from medical record review (based on whether visit resulted in admission, procedure/tests were conducted, whether the visit was for an accident or injury) | 40% | Adults across the U.S who participated in the National Medical Expenditure Survey and had a usual source of care other than the ED and who had a least one healthcare contact during 1996 or could not obtain needed care | 9146 | age, sex, race, education, health status, employment status, income, insurance, region of residence, and rural vs. urban residence |

| Schappert (1995)45 | Retrospective review of medical records | Determined retrospectively by medical record review (based on initial triage evaluation and diagnosis of presenting condition and whether patient required attention within several hours) | 55% | National sample of ED visits by adults (National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey) | Not described | None-Bivariate only |

| Shesser (1991)37 | Cross-sectional survey | Determined retrospectively by medical record review (based on vital signs, referral, hospital admission, chief complaint, arrival by ambulance) | 15% | Patients presenting to one urban ED during business hours | 549 | None-Bivariate only |

| Young (1996)39 | Cross-sectional survey | Determined prospectively at triage (based on whether patient could wait 12–24 hours for treatment) | 49% of ambulatory ED patients: 39% of all ED patients | Ambulatory patients ho presented to 56 hospital EDs across the U.S. | 6187 | None-Bivariate only |

No two studies used the same exact definition of non-urgent visits. Eleven articles (42%) identified non-urgent visits through retrospective review of medical records, 11 (42%) identified non-urgent visits prospectively at triage, and three articles (12%) used retrospective patient self-report (See appendix for additional detail on definitions). Across the relevant articles, the average fraction of all ED visits that were judged to be non-urgent (whether prospectively at triage or retrospectively following ED evaluation) was 37% (range: 8–62%). Four articles (15%) presented a conceptual framework to guide the study design and interpretation of results. Three articles used the Anderson model of healthcare utilization23,37,42 and one article used Mechanic’s model of illness behavior.41

In the reminder of this article, we summarize findings from the subset of articles (n=16) which included a comparison group of either urgent ED patients or all ED patients AND examined whether differences among these groups were statistically significant. We also include illustrative examples from the remaining studies (n=10) regarding self-reported reasons for non-urgent ED use and barriers to use of alternative locations.

Factors Associated with Non-Urgent ED Use

Age

Among the nine articles that examined age, six found that younger adults were more likely to have non-urgent visits compared to older adults.36,43–47 Effect sizes were generally large (OR>2). Three articles found no association between non-urgent ED use and age.23,38,48

Race

Among the nine articles that examined race, four articles found that Blacks were more likely than Whites to have a non-urgent visit.23,43,46,49 However, five articles reported no association;16,38,45,47,48 One study pointed out that Blacks had higher rates of non-urgent ED visits despite the fact that they were less likely to utilize healthcare in general.23

Gender

Findings were inconsistent across the 10 articles that examined gender. Four articles found that women were more likely than men to have a non-urgent visit,36,43,45,47 and two articles concluded the opposite (i.e., men were more likely than women to have a non-urgent visit).38,44 Four articles found no association.16,23,46,48

Income

Among the four articles that assessed income, 16,23,38,47 two reported that persons with low incomes were more likely to make non-urgent ED visits.23,47 Effect sizes were generally moderate (OR<2).

Insurance

Among the 13 articles that examined the uninsured, two found that uninsured patients were less likely to use the ED for non-urgent visits,23,50 two found that the uninsured were more likely,36,38 and five identified no association.16,40,45,48,51 One study found that the uninsured were more likely than Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) patients but less likely than Medicaid patients to have a non-urgent ED visit.52 Articles that looked at Medicaid patients found that either Medicaid was predictive of non-urgent ED use23,36,43,46,52 or there was no association.16,38,50,51 Effect sizes were generally moderate (OR<2).

Social Support

The only social support measure reported in the literature was marital status. Among the four articles that looked at the relationship between non-urgent ED use and marital status, no article identified an association.16,38,45,48

Health Status

Among the four articles that examined health status, two found that persons with poor health were more likely to have non-urgent visits,23,47 and two identified no association.16,45

Previous Healthcare Experiences

Previous healthcare experiences refer to an individual’s utilization history both within and outside of the ED. Two articles examined previous healthcare experiences. One article found that a recent hospitalization was associated with lower odds of having a non-urgent visit, more frequent ED visits was associated with higher odds of having a non-urgent visit, and the number of primary care visits had no association with having a non-urgent visit.48 In contrast, another article found that the average number of physician visits in an outpatient setting other than the ED was higher for persons with non-urgent ED visits.23

Culture/Community Norms and Personality

Culture/Community norms refers to the practices of others within one’s community (e.g., the propensity of neighbors to use the ED.) Personality factors are those related to an individual’s emotional, attitudinal, and behavioral response patterns. Examples of relevant traits include decision-making style and risk aversion. No article that compared non-urgent to urgent patients assessed culture or community norms or personality factors; however, one study of non-urgent patients found that personality factors such as coping mechanisms were not associated with going to the ED vs. PCP for a non-urgent condition.39

Perceived severity

Perceived severity refers to the patient’s perception of the urgency of his/her illness, which is a function of both personal beliefs and knowledge on what is an emergency. No article that compared non-urgent to urgent patients explored perceived severity; however four articles that focused only on non-urgent ED visits described patients’ perceptions of the urgency of their conditions. In these cases, the vast majority of patients (>80%) felt that their condition was urgent/could not wait for treatment.53–56

Convenience

Convenience refers to the ease with which a patient can seek care including travel, timing, and location. Among the three articles that discussed convenience,16,38,47 all found that convenience factors played a role in driving non-urgent ED use. For example, one study reported that the leading reason why the non-urgent group used the ED was “ease of use.”38 A descriptive study of non-urgent ED users found that 60% of non-urgent ED patients felt that the ED was more convenient than their PCP.55

Cost

Cost refers to the financial burden incurred by the patient. While no article that compared non-urgent to urgent patients assessed cost, one study of just non-urgent ED patients found that 42% chose the ED because of payment flexibility (i.e., no requirement to pay at the time of care.)54

Access

Access refers to the ability of the patient to obtain timely care outside the ED. Four articles found an association between poor access (e.g. difficulty in obtaining healthcare, not having a regular physician) and non-urgent ED use.16,40,45,47 Only one article identified no association between poor access and likelihood of having a non-urgent visit.48 Furthermore, a Harris Interactive survey reported that ED physicians felt that waiting times for appointments with PCPs and limited access to physicians on weekends were the leading reasons for non-urgent ED use.16 In a descriptive study of non-urgent ED patients, authors reported that the most significant barrier to getting care outside the ED was inability to get an appointment at a clinic.42

Referral/Advice

Referral/Advice refers to being counseled to go to the ED by a provider. Two articles (one with a comparison group and one of only non-urgent ED users) suggested that healthcare provider referral may be a substantial driving force in non-urgent attendance.38,55 One article found that about half of the non-urgent patients who presented during business hours were advised to go there by a PCP.55

Beliefs and knowledge about alternatives

Three articles (two with comparison groups and one of only non-urgent ED users) directly addressed beliefs about alternatives. One article reported that 76% of non-urgent ED users chose the ED because they felt they would receive better care there.54 A Harris Interactive survey reported that non-urgent ED users were more likely to think that other places were more expensive than the ED.16 Finally, another article found that persons who were not satisfied with their regular source of care were more likely to make a non-urgent visit to an ED.47

DISCUSSION

Due to the heterogeneity and limitations of the articles, it is challenging to summarize what drives the decision to seek ED care for non-urgent conditions. The limited evidence suggests that younger age, greater convenience of the ED compared to other ambulatory care alternatives, referral to the ED by a healthcare provider, and negative perceptions of non-ED care sites all play a role in decisions to seek care in the ED for non-urgent problems. Other factors appear unrelated to non-urgent ED use or more commonly, the results are inconclusive due to inconsistent results or because they have been studied rarely. Because of the weak evidence base, we argue that all of the factors assessed in the literature are candidates for future research.

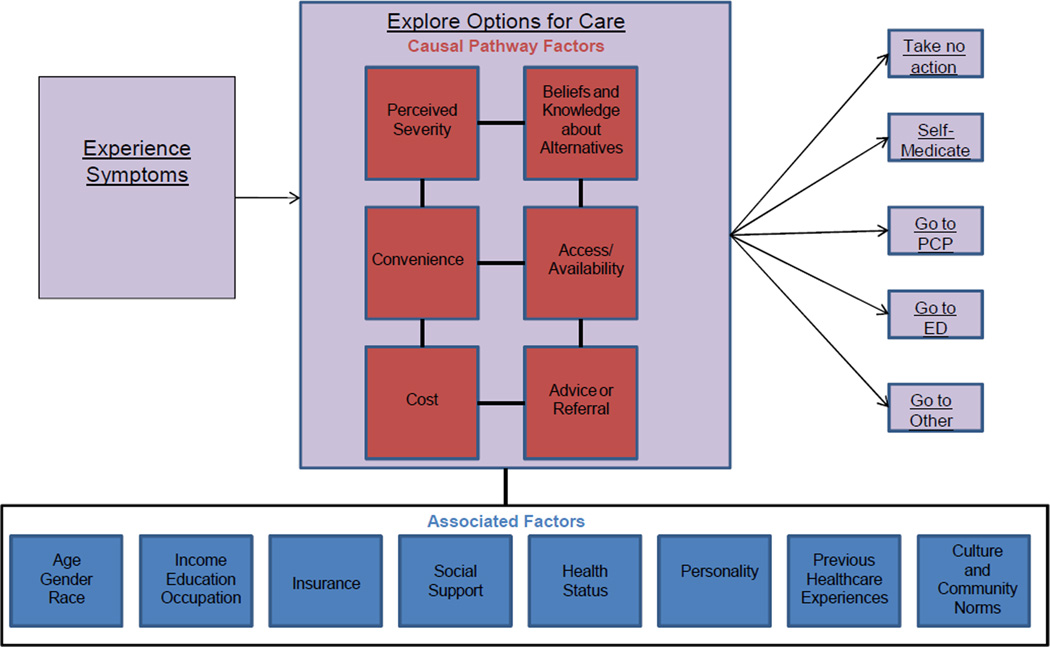

We believe a key limitation of these prior studies is the lack of a robust theoretical framework on what drives non-urgent ED use. To potentially guide future work, we created a theoretical model of the decision making process and factors that may influence a patient’s decision to visit the ED for a non-urgent condition. We based the model on review of included studies, as well as qualitative studies and commentaries.21,24,26,28,29,31,33,35,57 Qualitative studies which used patient interviews and focus groups were important to include because they generate hypotheses regarding reasons for use that can be probed in future empirical work.

The model depicted in Figure 2 suggests that a patient arrives at a decision to seek care in an ED by consciously or unconsciously weighing several considerations. First, the patient experiences acute symptoms – either a new problem or a flare-up of a chronic condition that is not immediately debilitating or clearly emergent (e.g. chest pain, signs of stroke). The patient then considers various options including going to the ED, going to another location, or not seeking care.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Model of Non-Urgent ED Use

In our model the decision to go the ED is influenced by an array of causal pathway factors and associated factors. While ALL of the factors depicted in the model likely influence non-urgent ED use, the causal pathway factors act as independent predictors. In contrast, we believe associated factors influence ED use via one of the causal pathway factors. For example, while certain models suggest that gender may be associated with non-urgent use, there is no a priori explanation as to why gender would be influential. We believe that gender, an associated factor, could possibly impact the decision to seek care in the ED for a non-urgent condition by affecting the perceived severity of the condition and beliefs and knowledge about alternatives (both causal pathway factors). In our review, the distinction between causal pathway and associated factors is also important as almost all interventions to decrease non-urgent ED use focus on causal pathway factors.

Although our model does not directly address healthcare supply because we focus on the perspective of the individual patient, one could imagine that the availability (or lack thereof) of options, including a limited supply of providers or an extended wait to be seen, could raise or lower the threshold for seeking care. In addition, while features of the healthcare system such as overall access to care or societal context are not the focus of our framework, they play a role in an individual’s decision-making by influencing their knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes about alternative locations for care.

The literature we reviewed on non-urgent ED use has several key limitations. First, descriptive studies of just non-urgent ED visits are hard to interpret. For example, although the self-perceived severity of their problem was high among patients who visited the ED for what others judged to be non-urgent, we do not know if perceived severity is similar among those who go to other care sites. Second, the comparison of urgent vs. non-urgent ED visits used in the vast majority of studies may be flawed. Urgent problems (e.g. chest pain) are qualitatively different than non-urgent problems (e.g. sore throat). The more relevant question is: why does the patient with a self-recognized non-urgent problem choose the ED rather than seek care at an alternative location or simply stay home? Only two studies compared non-urgent ED visits to non-urgent PCP visits; 37,39 however, we cannot draw conclusions based on these papers because they did not evaluate similar independent variables. Ideally, future studies would also include patients who became ill with a time-limited condition but chose not to seek care. Third, studies disproportionately focus on associated factors (e.g., age, gender) which are easy to measure and classify but do not provide a causal mechanism for driving non-urgent ED use and are difficult or impossible to modify. We hope that our theoretical model can guide future work to assess the frequency and relative importance of different causal factors.37,39 Fourth, there are problems in clarifying the relationship between predictors of non-urgent ED use and the definition of non-urgent use itself. For example, based on current research it is unclear whether older adults are in fact less likely to go to the ED for minor conditions or whether their visits are more likely to be deemed “urgent” because they are frail or have multiple co-morbid conditions. Lastly, health services research often makes broad generalizations about populations. Because non-urgent ED users are likely a diverse group, the better approach might be to try and break up non-urgent ED users into different strata.38 For example, some individuals may be using the ED due to habit, preference, or lack of education regarding alternatives. The intervention chosen might vary by the different strata. Prior to applying them, the precise issues or challenges need be identified so that the correct intervention(s) is applied to encourage or enable desired behavior by patients.

It is widely presumed that redirecting non-urgent visits to alternate settings is a desirable policy goal, if for no other reasons than to reduce healthcare spending and enable EDs to focus their efforts on more acutely ill and injured patients. However, efforts to deter non-urgent ED use could produce unintended consequences. Imposition of steep copayments and deductibles to discourage ED use may deter some patients from timely care-seeking for serious or even life-threatening problems. Even steering patients to alternate settings from the ED triage desk is not without risk. Some studies have shown that as many as 3–5% of patients triaged as “non-urgent” require immediate hospitalization after further evaluation in the ED.40 Another unintended consequence to consider is increased utilization; efforts to encourage alternatives to the ED, such as retail clinics, may induce patients who previously would have stayed at home to seek care. Likewise, it is only acceptable to discourage non-urgent use in communities where patients have real alternatives such as accessible primary care providers. High rates of non-urgent ED visits can in fact be an indicator of poor primary care access, as suggested by the ED Use Profiling Algorithm which classifies ED visits by whether they could be treated elsewhere or although emergent, could have been prevented by earlier access to primary care.58

LIMITATIONS

The major limitation of this review is that the validity of findings is limited by the quality of included articles. Few studied used multivariate statistics so we are unsure whether the identified factors are associated with non-urgent ED use controlling for other factors. Also, the diverse (and controversial) criteria used to define non-urgent visits limits the comparability of findings.

CONCLUSION

Despite the significant policy interest in deterring non-urgent ED use, our literature review highlights both the limited understanding of what drives non-urgent ED use and flaws in most of the published studies. If health plans, policy makers and providers want to reduce use of the ED for non-urgent problems, they must ensure that their interventions are evidence-based and tailored to address the needs and concerns of the populations they are designed to serve.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Socio-Demographic Factors Associated with Non-Urgent Use (n=16)**

| Factors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Age | Gender | Race | Income | Education | Employment tatus |

Insurance |

| Bond (1999)58 | Uninsured/public aid more likely (71%) than insured (53%) | ||||||

| Campbelll (1998)35 | Younger age groups (37–42%) more likely than older adults (11%) | Females (41%) more likely than males (28%) | No association | Medicaid (42%) or uninsured (44%) more likely than private insurance (25%) or Medicare (12%) | |||

| Cunningham (1995)22 | No association | No association | Blacks greater likelihood than Whites (OR: 1.68) | Lower income Greater likelihood than high income (OR: 1.38) | Lower education greater likelihood than higher education (OR: 1.03) | Medicaid greater likelihood than uninsured (OR: 1.47) Medicare greater likelihood than uninsured (OR: 1.61) | |

| Davis (2010)43 | Adults age 18–49 greater likelihood than older adults (OR: 5.0) | Males greater likelihood than females (OR: 1.25) | |||||

| Doty (2005)48 | Blacks (35%) more likely than Whites (20%) or Hispanics (17%) No association Whites vs. Hispanics | ||||||

| Garcia (2010)50 | No association comparing Medicaid, private insurance, and uninsured | ||||||

| Harris Interactive (2005)15 | No association | No association | No association | No association | No association | ||

| Gooding (1996)51 | Uninsured greater likelihood than HMO (OR: 1.12) Medicaid greater likelihood than uninsured (OR: 1.15) | ||||||

| Han (2003)47 | No association | No association | No association | No association | No association | ||

| Liu (1999)42 | Younger age greater likelihood than older age (OR: 1.79) | Females greater likelihood than males (OR: 1.12) | Blacks greater likelihood than hites (OR: 1.08) | Medicaid greater likelihood than private insurance (OR: 1.14) Private insurance greater Likelihood than Medicare (OR: 1.33) | |||

| Petersen (1998)44 | Adults age 16–30 greater likelihood than >60 (OR: 4.8) Adults age 31–40 greater likelihood than >60 (OR: 6.5) | Females greater likelihood than males (OR 1.3) | No association | No association | No association | ||

| Rubin (1995)49 | Higher % of the urgent group self pay (33%) vs. non-urgent group (22%) Higher % of non-urgent group commercial/HMO (38%) vs. urgent group (25%) No association between level of urgency and Medicare and Medicaid | ||||||

| Sarver (2002)46 | Females greater likelihood than males (OR: 1.44) | No association | Low income greater likelihood than higher income (OR: 1.70) | No association | |||

| Schappert (1995)45 | Adults 15–24 higher rate of non-urgent visits (26.3 visits per 100 persons per year) vs. all other age groups | No association | Blacks higher rate of non-urgent visits (31.8 visits per 100 persons per year) vs. Whites (18.3 visits per person per year) | Medicaid patients made up a larger % of all non-urgent visits (25%) as compared to urgent visits (20%) | |||

| Shesser (1991)37 | No association | Non-urgent group higher % of males (53% vs. 42%) than group of all ED patients | No association | No association | No association | Non-urgent group higher % of self-pay (23% vs.15%) and a lower % of Medicare (2% vs. 9%) than group of all ED patients No association between level of urgency and commercial insurance, HMO, and Medicaid | |

| Young (1996)39 | No association | ||||||

The majority of finding in the table are completed by adding the phrase “to have a non-urgent ED visit.”

If an article (n=16) did not contain any of the factors listed in the table, it was not included in the table.

Only statistically significant findings are reported (p<.05). Non-significant findings are reported as “no association.”

Table 4.

Miscellaneous Factors Associated with Non-Urgent Use (n=16)**

| Factors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Marital Status | Health Status | Previous Healthcare Experiences | Convenience | Access | Referral/ Advice |

Beliefs and knowledge about alternatives |

| Cunningham (1995)22 | Poor health greater likelihood than excellent health (OR: 2.17) | Average number of visits in an outpatient setting other than the ED higher for persons with non-urgent ED visits versus persons with only outpatient physician visits (5.6 vs. 4.8) | |||||

| Davis (2010)43 | Adult without chronic conditions greater likelihood than those with a chronic condition (ORs: 1.11–1.67) | ||||||

| Harris Interactive (2005)15 | No association | No association | Non-urgent ED users (27%) more likely to not want to miss work than all ED users (15%) | Having a regular physician higher among non-urgent ED users vs. all ED users (35% vs. 27%) | Non-urgent ED users (20%) more likely than all ED users to think other places are more expensive than the ED (12%) | ||

| Han (2003)47 | No association | No recent hospitalization associated with higher odds of non-urgent ED visit (OR: 1.85) More frequent ED visits associated with increased odds of non-urgent ED visit (OR: 1.16) No association (number of primary care visits) | No association (self-reported difficulty getting healthcare) | ||||

| Petersen 1998)44 | No association | No association | Persons without a regular physician greater likelihood than those with one (OR: 1.6) | ||||

| Sarver (2002)46 | Poor health greater likelihood than good health (OR: 2.94) | Persons who said it was difficult to obtain an appt with their usual source of care more likely (9%) than not difficult (5%) Persons with a wait time of more than an hour at their usual source of care more likely (9%) than no appt needed (5%) | Dissatisfaction with regular source of care associated with non-urgent visit (OR: 1.13) | ||||

| Shesser (1991)37 | No association | ||||||

| Young (1996)39 | Patients with a usual source of care more likely to be assessed as urgent (55%) compared to those without (46%) | Referred to the ED more likely to be assessed as urgent (61%) than not referred (49%) | |||||

The majority of finding in the table are completed by adding the phrase “to have a non-urgent ED visit.”

If an article (n=16) did not contain any of the factors listed in the table, it was not included in the table

Only statistically significant findings are reported (p<.05). Non-significant findings are reported as “no association.”

Take-Away Points.

Articles on the topic of non-urgent ED use were very heterogeneous with respect to study design, population, comparison, group, and non-urgent definition.

The limited evidence suggests that younger age, convenience of the ED compared to alternatives, referral to the ED by a physician, and negative perceptions about alternatives such as primary care providers all play a role in driving non-urgent ED use.

Efforts to deter non-urgent ED use can produce unintended consequences that must be considered.

Future studies would benefit from the use of a robust theoretical framework on what drives non-urgent ED use.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by the California Healthcare Foundation

Appendix

Definitions of Non-Urgent Visits

Among articles that reviewed medical records retrospectively, criteria used to define non-urgent visits included admission to hospital,36,38,47,48,59 diagnoses,37,44,46,59 vital signs,36,38,48 complaint,36,38,48 timing of visit,36,59 arrival to ED (e.g., non-ambulance),38,59 procedures and/or tests ordered,44,47,52 patient’s ability to wait for evaluation or care,43,46,51 co-morbidities,36,48 whether visit was for an accident/injury,47 triage evaluation,46 and referral.38 Among articles that determined level of urgency at triage, criteria included: vital signs,42,45,50,54,55 ability of patient to wait for evaluation or care,40,53,56,60, expectations of procedures/treatments/resources,42,54,55 symptoms,45,50,55 age,45 responsiveness,54 level of distress,54 medical history,45 duration of symptoms,45 referral,50 and complaint.50 Among articles that asked patients to retrospectively self-report the urgency of their visit, criteria included whether patient could have been seen by a primary care provider,16,49 admission to hospital,23 whether visit was for an accident/injury,23 procedures performed,23 referral,23 arrival to ED,23 perceived seriousness of condition,23 ability of patient to wait for evaluation or care,16 and timing of visit.16

References

- 1.Young G, Wagner M, Kellermann A, Bouley E. Ambulatory visits to hospital emergency departments. Patterns and reasons for use. 24 Hours in the ED Study Group. JAMA. 1996;276(6):460–465. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.6.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niska R, Bhuiya F, Xu J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 Emergency Department Summary. National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Northington W, Brice J, Zou B. Use of an emergency department by nonurgent patients. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2005;23:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carret M, Fassa A, Domingues M. Inappropriate use of emergency services: a systematic review of prevalence and associated factors. Cad. Saúde Pública. 2009;25(1):7–28. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durand A, Gentile S, Devictor B, et al. ED patients: how nonurgent are they? Systematic review of the emergency medicine literature. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guttman N, Zimmerman D, Nelson M. The Many Faces of Access: Reasons for Medically Nonurgent Emergency Department Visits. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2003;28(6) doi: 10.1215/03616878-28-6-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kellerman A. Nonurgent emergency department visits. JAMA. 1994;271:1953–1955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Center for Health Statistics. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2008 Emergency Department Summary Tables. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redstone P, Vancura J, Barry D, Kutner J. Nonurgent Use of the Emergency Department. J Ambulatory Care Manage. 2008;31(4):370–376. doi: 10.1097/01.JAC.0000336555.54460.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phelps K, Taylor C, Kimmel S, Nagel R, Klein W, Puczynski S. Factors Associated With Emergency Department Utilization for Nonurgent Pediatric Problems. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1086–1092. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carret M, Fassa A, Kawachi I. Demand for emergency health service: factors associated with inappropriate use. BMC Health Services Research. 2007;7:131. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham P, Clancy C, Cohen J, Wilets M. The use of hospital emergency departmetns for nonurgent health problesm. Medical Cae Research and Review. 1995;52(4):453–474. doi: 10.1177/107755879505200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinick R, Burns R, Mehrotra A. Many Emergency Department Visits Could Be Managed At Urgent Care Centers And Retail Clinics. Health Affairs. 2010;29(9):1630–1636. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosseini N, Weinberg S. The Effect of the Massachusetts Healthcare Reform on Emergency Department Use. Association for Public Policy and Management. Boston. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pitts S, Carrier E, Rich E, Kellermann A. Where Americans Get Acute Care: Increasingly, It’s Not At Their Doctor’s Office. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(9):1620–1629. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris Interactive. Emergency Department Utilization in California: Survey of Consumer Data and Physician Data. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Washington D, Stevens C, Paul C, Henneman P, Brook R. Next-Day Care for Emergency Department Users with Nonacute Conditions: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2002;137:707–714. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-9-200211050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grumbach K, Keane D, Bindman A. Primary care and public emergency department overcrowding. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(3):372–378. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mortensen K. Copayments Did Not Reduce Medicaid Enrollees’ Nonemergency Use Of Emergency Departments. HEALTH AFFAIRS. 29(9):1643–1650. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0906. 210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nawar E, Niska R, Xu J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2005 Emergency Department Summary. Hyattsville National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kellermann AL. Nonurgent emergency department visits. Jama. 1994 Jun 22–29;271(24):1953–1954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wharam J, Landon B, Galbraith A, Kleinman K, Soumerai S, Ross-Degnan D. Emergency department use and subsequent hospitalizations among members of a high-deductible health plan. Jama. 2008;297(10):1093–1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cunningham PJ, Clancy CM, Cohen JW, Wilets M. The use of hospital emergency departments for nonurgent health problems: a national perspective. Med Care Res Rev. 1995 Nov;52(4):453–474. doi: 10.1177/107755879505200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carret ML, Fassa AC, Domingues MR. Inappropriate use of emergency services: a systematic review of prevalence and associated factors. Cad Saude Publica. 2009 Jan;25(1):7–28. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richardson L, Hwang U. Access to care: a review of the emergency medicine literature. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2001;8(11):1030–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Felland LE, Hurley RE, Kemper NM. Safety net hospital emergency departments: creating safety valves for non-urgent care. Issue Brief Cent Stud Health Syst Change. 2008 May;(120):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodgins MJ, Wuest J. Uncovering factors affecting use of the emergency department for less urgent health problems in urban and rural areas. Can J Nurs Res. 2007 Sep;39(3):78–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howard MS, Davis BA, Anderson C, Cherry D, Koller P, Shelton D. Patients' perspective on choosing the emergency department for nonurgent medical care: a qualitative study exploring one reason for overcrowding. J Emerg Nurs. 2005 Oct;31(5):429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koziol-McLain J, Price DW, Weiss B, Quinn AA, Honigman B. Seeking care for nonurgent medical conditions in the emergency department: through the eyes of the patient. J Emerg Nurs. 2000 Dec;26(6):554–563. doi: 10.1067/men.2000.110904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simonet D. Cost reduction strategies for emergency services: insurance role, practice changes and patients accountability. Health Care Anal. 2009 Mar;17(1):1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10728-008-0081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guttman N, Zimmerman DR, Nelson MS. The many faces of access: reasons for medically nonurgent emergency department visits. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2003 Dec;28(6):1089–1120. doi: 10.1215/03616878-28-6-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liggins K. Inappropriate attendance at accident and emergency departments: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 1993 Jul;18(7):1141–1145. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18071141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoot NR, Aronsky D. Systematic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Emerg Med. 2008 Aug;52(2):126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Durand AC, Gentile S, Devictor B, et al. ED patients: how nonurgent are they? Systematic review of the emergency medicine literature. Am J Emerg Med. 2011 Mar;29(3):333–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Padgett DK, Brodsky B. Psychosocial factors influencing non-urgent use of the emergency room: a review of the literature and recommendations for research and improved service delivery. Soc Sci Med. 1992 Nov;35(9):1189–1197. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90231-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell PA, Pai RK, Derksen DJ, Skipper B. Emergency department use by family practice patients in an academic health center. Fam Med. 1998 Apr;30(4):272–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Butler PA. Medicaid HMO enrollees in the emergency room: use of nonemergency care. Med Care Res Rev. 1998 Mar;55(1):78–98. doi: 10.1177/107755879805500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shesser R, Kirsch T, Smith J, Hirsch R. An analysis of emergency department use by patients with minor illness. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(7):743–748. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)80835-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz MP. Office or emergency department: what’s the difference? South Med J. 1995 Oct;88(10):1020–1024. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199510000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young GP, Wagner MB, Kellermann AL, Ellis J, Bouley D. Ambulatory visits to hospital emergency departments. Patterns and reasons for use. 24 Hours in the ED Study Group. Jama. 1996 Aug 14;276(6):460–465. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.6.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacLean SL, Bayley EW, Cole FL, Bernardo L, Lenaghan P, Manton A. The LUNAR project: A description of the population of individuals who seek health care at emergency departments. J Emerg Nurs. 1999 Aug;25(4):269–282. doi: 10.1016/s0099-1767(99)70052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brim C. A descriptive analysis of the non-urgent use of emergency departments. Nurse Res. 2008;15(3):72–88. doi: 10.7748/nr2008.04.15.3.72.c6458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu T, Sayre MR, Carleton SC. Emergency medical care: types, trends, and factors related to nonurgent visits. Acad Emerg Med. 1999 Nov;6(11):1147–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davis JW, Fujimoto RY, Chan H, Juarez DT. Identifying characteristics of patients with low urgency emergency department visits in a managed care setting. Manag Care. 2010 Oct;19(10):38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petersen L, Burstin H, O’Neil A, Orav E, Brennan T. Nonurgent emergency department visits: the effect of having a regular doctor. Med Care. 1998;36(8):1249–1255. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199808000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schappert SM. The urgency of visits to hospital emergency departments: data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS), 1992. Stat Bull Metrop Insur Co. 1995 Oct-Dec;76(4):10–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarver JH, Cydulka RK, Baker DW. Usual source of care and nonurgent emergency department use. Acad Emerg Med. 2002 Sep;9(9):916–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb02193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han B, Wells BL. Inappropriate emergency department visits and use of the Health Care for the Homeless Program services by Homeless adults in the northeastern United States. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2003 Nov-Dec;9(6):530–537. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200311000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Doty MM, Holmgren AL. Health care disconnect: gaps in coverage and care for minority adults. Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey (2005) Issue Brief Cent Stud Health Syst Change. 2006 Aug;21:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rubin MA, Bonnin MJ. Utilization of the emergency department by patients with minor complaints. J Emerg Med. 1995 Nov-Dec;13(6):839–842. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(95)02013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garcia TC, Bernstein AB, Bush MA. Emergency department visitors and visits: who used the emergency room in 2007? NCHS Data Brief. 2010 May;38):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gooding SS, Smith DB, Peyrot M. Insurance coverage and the appropriate utilization of emergency departments. J Public Policy Mark. 1996 Spr;15(1):76–86. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gill JM, Riley AW. Nonurgent use of hospital emergency departments: urgency from the patient’s perspective. J Fam Pract. 1996 May;42(5):491–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Northington WE, Brice JH, Zou B. Use of an emergency department by nonurgent patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2005 Mar;23(2):131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Redstone P, Vancura JL, Barry D, Kutner JS. Nonurgent use of the emergency department. J Ambul Care Manage. 2008 Oct-Dec;31(4):370–376. doi: 10.1097/01.JAC.0000336555.54460.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baker DW, Stevens CD, Brook RH. Determinants of emergency department use by ambulatory patients at an urban public hospital. Ann Emerg Med. 1995 Mar;25(3):311–316. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Resar R, Griffin F. Rethinking Emergency Department Visits. J Ambulatory Care Manage. 2010;33:290–295. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e3181f53424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.DeLia D, Cantor J. Emergency department utilization and capacity: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coleman EA, Eilertsen TB, Magid DJ, Conner DA, Beck A, Kramer AM. The association between care co-ordination and emergency department use in older managed care enrollees. Int J Integr Care. 2002;2:pe03. doi: 10.5334/ijic.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bond T, Stearns S, Peters M. Analysis of chronic emergency department use. Nurs Econ. 1999;17(4):207–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.