Abstract

Introduction

Post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS) is a serious complication of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of the leg that affects 20–50% of patients. Once a patient experiences PTS there is no treatment that effectively reduces the debilitating complaints. Two randomised controlled trials showed that elastic compression stocking (ECS) therapy after DVT for 24 months can reduce the incidence of PTS by 50%. However, it is unclear whether all patients benefit to the same extent from ECS therapy or what the optimal duration of therapy for individual patients should be. ECS therapy is costly, inconvenient, demanding and sometimes even debilitating. Tailoring therapy to individual needs could save substantial costs. The objective of the IDEAL DVT study, therefore, is to evaluate whether tailoring the duration of ECS therapy on signs and symptoms of the individual patient is a safe and effective method to prevent PTS, compared with standard ECS therapy.

Methods and analysis

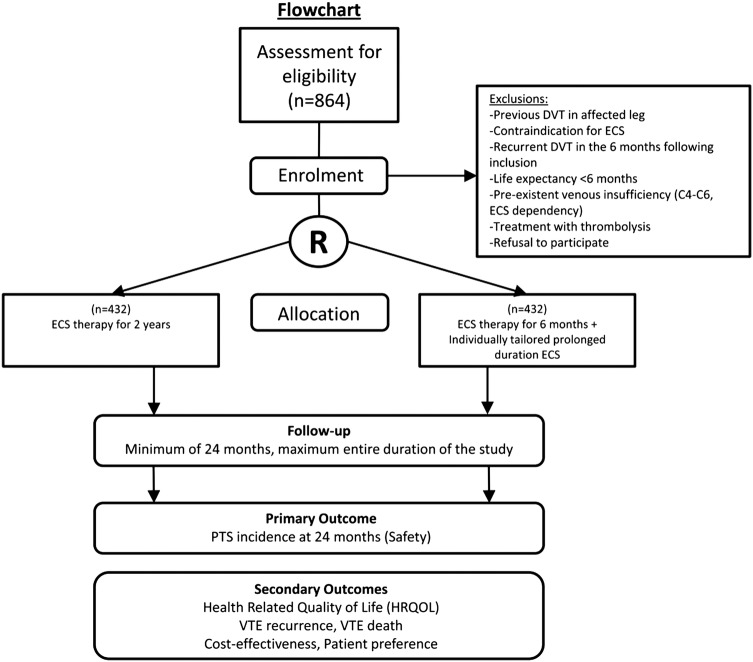

A multicentre, single-blinded, allocation concealed, randomised, non-inferiority trial. A total of 864 consecutive patients with acute objectively documented proximal DVT of the leg are randomised to either standard duration of 24 months or tailored duration of ECS therapy following an initial therapeutic period of 6 months. Signs and symptoms of PTS are recorded at regular clinic visits. Furthermore, quality of life, costs, patient preferences and compliance are measured. The primary outcome is the proportion of patients with PTS at 24 months.

Ethics and dissemination

Based on current knowledge the standard application of ECS therapy is questioned. The IDEAL DVT study will address the central questions that remain unanswered: Which individual patients benefit from ECS therapy and what is the optimal individual treatment duration? Primary ethics approval was received from the Maastricht University Medical Centre.

Results

Results of the study will be disseminated via peer-reviewed publications and presentations at scientific conferences.

Trial registration number

NCT01429714 and NTR 2597.

Keywords: Post thrombotic syndrome, Deep vein thrombosis, Elastic compression stocking therapy, Protocol, RCT

Background

After deep vein thrombosis (DVT) 20–50% of patients develop post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS). PTS is a chronic condition characterised by leg complaints such as pain, heaviness, cramps, aching, tingling and leg signs due to venous insufficiency, evolving, in severe cases, to venous ulceration of the DVT-affected leg.1–4 PTS is a serious affliction with substantial impact on quality of life and costs.1 5 Because an effective therapy is lacking, prevention of PTS is of major importance.

Until now, elastic compression stocking (ECS) therapy after DVT has been the mainstay of PTS prevention. The evidence sustaining the value of ECS therapy following acute DVT is derived from two randomised clinical trials, which showed that incidences of PTS were reduced by approximately 50% with application of ECS therapy for 24 months.6 7 However, based on these trials it is still undecided whether all patients benefit to the same extent from ECS therapy or what the optimal duration of ECS therapy for individual patients should be. We have previously assessed the safety of a shortened duration of ECS therapy based on individual patient clinical scores in a management study of 125 patients, and we have shown that tailoring the duration of ECS therapy based on the signs and symptoms of the individual patient after an initial treatment period of 6 months is a safe strategy to prevent PTS. We found that 50% of our patients did not need ECS therapy for as long as 2 years, while the overall incidence of PTS was 21.1% (95% CI 13.5% to 28.7%).8 This incidence is comparable to published incidences after 24 months of ECS therapy.6 7 While this was a prospective management cohort study with an open character and therefore prone to bias, the results of this study need to be confirmed by an adequately powered randomised controlled trial.

There have been other studies that highlighted different aspects of ECS therapy. ECS therapy may not be indicated for all patients, as shown by a study that assessed whether ECS therapy initiated 1 year after the event of DVT would lower the incidence of PTS in patients without complaints but with reflux on duplex testing. No significant benefit of ECS therapy at this late time of onset was found. The incidence of PTS was low in both groups.9 One study so far assessed whether prolonged duration of ECS therapy was superior to 6 months of ECS therapy following an event of proximal DVT. In this study, no significant difference in the incidence of PTS according to the Clinical-Etiology-Anatomy-Pathophysiology (CEAP) classification was observed between the two treatment groups.10

The proposed IDEAL (individually tailored elastic compression against (=vs) long-term therapy) DVT study is a non-inferiority trial and aims to demonstrate that the assessed alternative therapy based on ECS for 6 months followed by individually prolonged ECS therapy based on Villalta scores is non-inferior to the comparator ECS therapy for a standard duration of 24 months. In addition, we are interested in studying the cost-effectiveness of individual tailoring of the duration of ECS therapy via a cost-utility analysis (CUA) and we want to retrieve information on the patient's motivations for compliance or non-compliance to therapy. Because compliance to therapy is one of the most important prerequisites for successful ECS therapy, a discrete choice experiment (DCE) will be performed in which patient preferences towards ECS therapy will be assessed, in order to reveal the main obstacles for compliance to therapy. For this purpose, a DCE questionnaire will be sent to a subset of the population (300 patients) approximately 3 months after DVT.

The results of a recently published placebo-controlled trial performed by Kahn et al11 refuted the routine wearing of ECS after DVT altogether. This study showed no treatment effect at all from ECS therapy in contrast to the large treatment effects found in previous non-placebo-controlled trials.6 7 The unexpected lack of effectiveness cannot be dismissed solely as a placebo effect. The compliance to ECS therapy, a major determinant of effectiveness, was 55.6% after 24 months. This was less in comparison to the previous trials by Brandjes et al 6 and Prandoni et al,7 where compliance was up to 90%.11 Although a per protocol analysis of the patients reporting regular stocking use yielded the same outcome, this subanalysis may not be adequately powered to dismiss lack of compliance as an important determinant of non-effectiveness.

Based on current knowledge, it is therefore understood that the standard application of ECS therapy is questioned. Especially the benefit to individual patients and the optimal duration of ECS therapy were never studied properly and as a result it is unclear which individual patients require therapy and for how long.

The IDEAL DVT study aims to address these topics. In addition, quality of life, patient preference towards ECS therapy, compliance to therapy as well as cost-effectiveness of ECS therapy will be assessed.

The primary outcome of the IDEAL DVT study will be PTS at 24 months after the event. The secondary outcomes will be: (1) health-related quality of life (HRQOL), measured by questionnaires (Short Form (SF)-36,12 EuroQOL (EQ)-5D,13 Dutch translated Veines-Qol14); (2) costs;15 (3) recurrent thrombosis, according to criteria as published16 and assessed by objective tests; (4) venous thromboembolism (VTE)-related death during follow-up, assessed by an independent and blinded adjudication committee; (5) patient preferences, assessed with a DCE.17

The scope of the problem in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, each year, around 25 000 patients experience a new event of DVT. To prevent PTS, the common practice is to prescribe custom fitted ECS therapy for 2 years for all patients.18 19 ECS therapy is costly, demanding and sometimes even debilitating. Elderly patients can often not apply the ECS by themselves but need help from family or they even need home care visits (7.5%).20–22 Total annual costs of ECS therapy roughly amounts to €2.5 million for stockings (25 000 patients×€100) and €21 million for home care (7.5%×25 000 patients×500 visits×€20).20–22 Moreover, the majority of patients do not experience any post-thrombotic symptoms.9 In the Netherlands, over €10 million each year could be saved if ECS treatment could be individualised.

Methods/design

A multicentre, single-blinded, allocation concealed, randomised, non-inferiority trial comparing individually tailored duration of ECS therapy (intervention) with standard duration of 24 months ECS therapy (control), for the prevention of PTS. Randomisation will guarantee a balanced distribution of patients within each patient group. Stratification will be performed on centre and potentially confounding effects such as age, sex and body mass index (BMI). The study will be a multicentre study in order to get a good representation of patients and to achieve sufficient patient numbers. The primary outcome will be PTS at 24 months after the event; the observers will be blinded to the allocated treatment arm. The allocation will be concealed from study personnel involved in assessing the leg symptoms and rating the PTS scores. Both randomisation and allocation concealment are used as strategies against bias. The study is not double blinded; no inactive stockings will be used in the comparator group. The use of sham stockings will very likely interfere with the quality of life and will complicate the assessment of perceived differences between groups. Patients will be followed for the entire study duration; incidence of recurrent DVT and VTE-related death during the follow-up period will be documented.

Patients and treatment

Consecutive, consenting adults with an acute objectively documented proximal DVT of the leg, adequately treated with anticoagulant treatment and initial compression therapy according to a prespecified protocol are included in the study. Patients are included and randomised in the IDEAL DVT study within 2–6 weeks after DVT.

Exclusion criteria are:

Previous DVT in the affected leg. Patients with a previous ipsilateral DVT might already have developed PTS after the first DVT.

Recurrent DVT in the 6 months following inclusion, as it cannot be justified to advise these patients to discontinue ECS therapy 6 months after DVT.

Pre-existent venous insufficiency (skin signs C3–C6 on CEAP score or requiring ECS therapy). Pre-existent venous insufficiency increases the risk of developing PTS and the majority of patients with venous insufficiency already chronically wear ECSs. In addition, venous insufficiency is closely related to PTS and is therefore difficult to differentiate from PTS.

Contraindication for ECS therapy, such as intermittent claudication or clinical signs of leg ischaemia or asymptomatic arterial insufficiency (a pulse deficit or bruit at sites of narrowing at physical examination).

Active thrombolysis, as thrombolysis reduces the risk of PTS.

Limited life expectancy (<6 months), as the follow-up period is 2 years.

Patients are recruited from 12 hospitals in the Netherlands and 2 hospitals in Italy.

There is a prespecified protocol for the management of DVT in all participating centres.

In the initial acute phase after DVT, until the acute oedema has disappeared, one of three strategies will be applied. The leg is either bandaged with short stretch bandages to a compression of 30–40 mm Hg, worn day and night and redressed twice per week; or a bandage stocking with 35 mm Hg compression is prescribed (Mediven Struva 35, Medi, Breda, the Netherlands), and worn day and night; or no initial compression therapy is applied, according to the prespecified strategy of the hospital protocol. After the initial phase, a custom-fitted, flat-knitted, knee length graduated ECS class III (ankle pressure 40 mm Hg) is prescribed for all patients. The same brand and type (Mediven 550) of compression stocking is prescribed to all patients in all participating centres. Compression therapy with the ECS is started immediately after the initial phase, so there is no period without compression in between, with exception of the patients who do not receive compression in the initial phase. Patients receive two new stockings every year. Patients are advised to wear the stockings during the daytime.

Procedures

After obtaining written informed consent, randomisation is performed centrally at the coordinating study centre, the Maastricht University Medical centre. Patients are included and randomised within 2–6 weeks after diagnosis of DVT. Patients are randomised to one of the two treatment arms (figure 1). A web-based randomisation programme (TENALEA (Trans European Network for Clinical Trials Services)) is used that executes blocked randomisation with stratification on centre-level and on possible confounding patient characteristics such as age, sex and BMI (<26 to ≥26 kg/m2). Permuted blocks of randomly varying size are used to maintain balance of numbers in each treatment group and to ensure allocation concealment.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram (DVT, deep vein thrombosis; ECS, elastic compression stocking; PTS, post-thrombotic syndrome).

Information on allocation is only accessible to the study personnel at the coordinating study centre in Maastricht; patients will receive information about their allocation via the coordinating study centre. The allocation will be concealed from study personnel involved in assessing the leg symptoms and rating the PTS scores. Patients are not blinded by the use of sham stockings, because they may influence quality of life, complicating the assessment of perceived differences between groups. Patients are asked not to reveal their treatment allocation to their own physician, and not to wear the ECS at the day of their outpatient clinic visits.

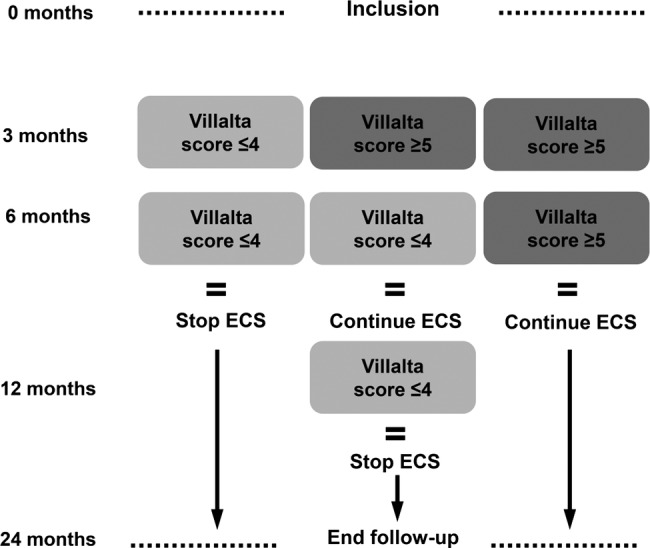

All patients are advised to wear the ECS during the first 6 months after DVT. In the control group, all patients are instructed to wear the ECS daily for a total duration of 2 years. In the intervention group, duration of ECS therapy is individually tailored based on Villalta scores.23 After the first 6 months, therefore, there are three scenarios:

The Villalta score at both the 3-month and 6-month follow-up visit is ≤4, in which case the patient is advised to discontinue ECS therapy.

The Villalta score at the 3-month follow-up visit is ≥5 and at the 6-month follow-up visit is ≤4. The patient is advised to continue the ECS therapy for another 6 months. If the Villalta score at the 12-month follow-up visit is ≤4, the patient is allowed to discontinue the ECS therapy.

The Villalta score is ≥5 at both the 3-month and 6-month follow-up visits. The patient is advised to continue the ECS therapy for a total duration of 24 months (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Algorithm individually tailored elastic compression stocking (ECS) therapy.

Using this algorithm the duration of ECS therapy is individually tailored to each patient. The decision on the duration of ECS therapy in patients in the intervention group is made centrally at the coordinating study centre, as the information on treatment allocation is available only there. The patient is informed about the decisions on the (dis) continuation of the ECS therapy by the coordinating centre.

When a patient develops symptoms and signs of PTS after discontinuation of ECS therapy, a predefined protocol is followed. If necessary, ECS treatment will be reinstated.

Follow-up

All patients are followed for 24 months after DVT. During these 24 months they visit the outpatient clinic four times: at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months after the DVT. At each follow-up visit the signs of PTS will be recorded and scored by the study nurse or the treating physician using the objective part of the Villalta clinical scale for PTS.23 In case of intermittent leg complaints or signs or symptoms suspected to be recurrent VTE, patients are instructed to visit their treating physician. Study documentation will be filled out and adverse events will be recorded. The CCMO (central committee human-related research) will be notified in case of serious adverse events or death.

The patient is asked to fill out five questionnaires: at baseline, and 3, 6, 12 and 24 months later. All questionnaires will be offered as a web-based application; each patient will have a unique personal entry code. For patients who are not able or willing to use the electronic questionnaires, a paper version will be available. The first questionnaire is filled out shortly after inclusion (4–6 weeks after DVT) and the subsequent questionnaires are filled out the day before each follow-up visit. All questionnaires contain the subjective part of the Villalta clinical scale for PTS,23 questions on ECS compliance, a cost questionnaire15 and three HRQOL questionnaires: the Dutch translated Veines-Qol,14 the SF-3612 and the EQ-5D.13 In a subset of the study population patient preferences regarding elastic compression therapy will be analysed by conducting a DCE. For this purpose, a DCE questionnaire will be sent to a subset of the population at approximately 3 months after DVT.

Compliance to ECS therapy is monitored in two ways. Each questionnaire contains a question on compliance to the advised version of ECS therapy. Because compliance and adherence to therapy is of crucial importance the number of contact moments for the assessment of compliance with ECS therapy will be increased by adding telephone contacts to the regular clinical visits. Study-supporting staff will make computer-assisted random telephone calls during the entire follow-up period to the patients in the group with the 2-year ECS intervention as well as to patients in the group with individualised ECS therapy. The telephone calls will be made randomly to create a surprise effect (patients are off guard) and to allow for a distribution of contacts over the entire study period. Per patient three extra contact moments will be created. A standard questionnaire will be used to assess compliance and to address reasons for non-compliance. Crossover to another therapy arm will be discussed and discouraged.

Outcomes

The primary outcome is the proportion of patients with PTS at the end of follow-up, 24 months after DVT. PTS is defined as a Villalta score of ≥5 at two consecutive visits that are at least 3 months apart. The time point of the second Villalta score of ≥5 will be considered the time point of PTS diagnosis. Although the consensus is to diagnose PTS at the 6-month visit or later based on one single Villalta score ≥5,24 we modelled this study after the preceding management study in which two consecutive Villalta scores ≥5 were needed for the diagnosis of PTS. We observed that a proportion of patients (about 12%) had fluctuating Villalta scores beyond 6 months after the acute event of DVT.8 Assigning the diagnosis based on one single score ≥5 would therefore lead to misclassification and overestimation of the PTS incidence. The Villalta scores at 6 months will be available; therefore, the proportion of patients with PTS according to the consensus scoring method will also be presented.

Secondary outcomes include: (1) HRQOL, measured by questionnaires (SF-36,12 EQ-5D,13 Dutch translated Veines-Qol14); (2) costs;15 (3) recurrent thrombosis, according to criteria as published16 and assessed by objective tests; (4) VTE-related death during follow-up, assessed by an independent and blinded adjudication committee; (5) patient preferences, assessed with a DCE.17

Since effects on costs as well as generic HRQOL are to be expected, the method of economic evaluation is a CUA. The analysis will be from a societal perspective. The primary effect parameter is generic HRQOL, measured in quality-adjusted life years. We will perform two analyses: a trial-based CUA with a time horizon of 2 years (identical to the duration of follow-up in the clinical study), and a model-based CUA with a lifelong time horizon. For the latter, we will follow the guidelines of good modelling.25 We will be able to adapt a Markov model for diagnostic strategies in DVT, which was developed by our group earlier.26 Costs in the economic analyses include direct healthcare costs (medical costs for prevention, diagnostics, therapy, rehabilitation and care), direct non-healthcare costs (travel costs) and indirect costs (productivity loss). Utilities will be calculated from the responses on the EQ-5D and SF-36 classification systems using the available multiattribute utility functions.27 28 Incremental cost-utility ratios will be calculated, and non-parametric bootstrap analyses will be used to quantify the uncertainty surrounding the cost-utility ratio of the trial-based analysis. Sensitivity analyses and subgroup analyses will be performed to assess the impact of variation in parameters and heterogeneity of the patient population.

ECS therapy has several disadvantages for the patients (stockings are uncomfortable, ugly and difficult to put on and take off), while duration and effectiveness are uncertain. A DCE will be conducted to assess the patient preferences regarding ECS therapy, providing insight to the trade-offs patients make between characteristics of the therapy when deciding to wear the stocking or not. Duration of ECS therapy is one of the characteristics. Data will be analysed using multinomial logit models and mixed logit models (Nlogit, Econometric Software).

Sample size calculation

The proposed study is a non-inferiority trial and aims to demonstrate that the assessed alternative therapy based on ECS for 6 months followed by individually prolonged ECS therapy based on Villalta scores is not worse than the comparator ECS therapy for a standard duration of 24 months, by more than the prespecified amount of 7.5% (the non-inferiority margin). The published incidence of PTS following 2 years of ECS lies between 20% and 30% (Prandoni et al7 24.5% (95% CI 15.6% to 33.4%) and Brandjes et al 6 20% (95% CI 12.4% to 29.2%). As it is statistically impossible to demonstrate equivalence (prove the H0 of no difference), Blackwelder29 proposed a one-sided significance test to reject the null hypothesis by a clinically acceptable amount. If we allow a difference of 7.5% in the outcome PTS between the group with ECS for 2 years and the group with the alternative therapy, 70% of the effect will be preserved. This proportion of loss in efficacy is customarily accepted in controlled randomised clinical trials. At a one-sided significance level of 0.05 and a power of 80%, with a ratio of 1, a total of 847 patients is needed to provide sufficient numbers for an adequately powered trial.29 30 Loss to follow-up of patients is expected to be less than 2% since the intervention does not have an invasive nature. Therefore, a total of 864 patients are needed (432 patients per treatment arm).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of the total population and of the two treatment groups separately will be computed to provide baseline characteristics of the patients in both treatment arms.

For the primary outcome PTS, univariate analysis of all proportions will be performed with logistic regression (χ2) analysis. Kaplan-Meier method will be used to calculate the cumulative incidences of PTS, adjusted for centre to compare incidence rates between the two treatment arms. Patients who die or are lost to follow-up will be censored at their last visit. Analysis of variance will be applied to assess changes over time by comparing different outcome measures at different time points of follow-up.

HRs and 95% CIs for both treatment arms will be calculated using Cox regression models. HRs will be stratified for centre and adjusted for age, sex, BMI, clinical presentation of DVT and extent of the index DVT.

Interim analysis (safety)

A prespecified safety analysis will be performed when 50% of the participants have completed the 2-year follow-up. The analysis will be performed by the coordinating centre, and supervised by the principal investigators. The safety analysis will be performed to assess significant enhanced risk of PTS or excess morbidity/mortality in the intervention arm of the study population. Fisher's exact test will be performed to compare incidence of PTS at a significance level of 0.05 (two-sided). The study can be stopped in case of significant excess morbidity/mortality in the alternative treatment arm.

Ethical considerations

All patients are extensively informed about the study and written informed consent is obtained from all participating patients.

The IDEAL DVT study started including patients on 11 March 2011 and inclusion is currently ongoing. Recruitment is expected to be terminated in January 2015. As the follow-up is 2 years, the results are expected within 3 years, in January 2017.

Discussion

Based on current knowledge, the standard application of ECS therapy after DVT is questioned. The definitive answer on the usefulness of ECS therapy for the prevention of PTS is not yet provided. Therefore, the need for the IDEAL DVT study remains unchanged. The benefit to individual patients and the optimal duration of ECS therapy were never studied properly and as a result it is unclear which individual patients require therapy and for how long. The IDEAL DVT study will address the central questions that remain unanswered: Which individual patients benefit from ECS therapy and what is the optimal individual treatment duration? The study that we plan to perform is not only innovative, for the first time individual tailoring of duration of ECS therapy will be investigated, but it will provide unique additional knowledge on the safety, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of this approach as well.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors especially acknowledge the participating investigators.

Footnotes

Collaborators : The IDEAL DVT investigators: The Netherlands: Maastricht, Maastricht University Medical Centre: AJtC-H, MD, PhD (principal investigator); HtC, MD, PhD; MJ, PhD; ACB, MD. Groningen, University Medical Centre Groningen: Karina Meijer, MD PhD. Amsterdam, Academic Medical Centre: Saskia Middeldorp, MD, PhD; Michiel Coppens, MD, PhD; Mandy N Lauw, MD; Y Whitney Cheung, MD. Heerlen, Atrium Medical Centre: Guy JM Mostard, MD; Asiong Jie, MD, PhD. Hoorn, Westfriesgasthuis: Simone M van den Heiligenberg, MD. Eindhoven, Maxima Medical Centre: Lidwine W Tick, MD, PhD; Marten R Nijziel, MD, PhD. Almere, Flevohospital: Marije ten Wolde, MD, PhD; Y Whitney Cheung, MD. Amsterdam, OLVG: Sanne van Wissen, MD, PhD; Wim E Terpstra, MD, PhD. Roermond, Laurentius hospital: Marlène HW van de Poel, MD. Amsterdam, Slotervaart hospital: Hans-Martin Otten, MD, PhD. Amsterdam, VU Medical Centre: Erik H Serné, MD, PhD. Nijmegen, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre: Edith H Klappe, MD, PhD; Mirian CH Janssen, MD, PhD; Tjerk de Nijs, MD. Italy: Padua, Aziende Ospedaliera di Padova: Paolo Prandoni, MD, PhD. Treviso, Aziende ULSS: Sabina Villalta, MD.

Contributors: AJtC-H wrote the protocol and designed the study. The other authors MJ (cost-effectiveness research), MP (study design/statistics) and HtC (study design) contributed. ACB is a PhD student and coordinator of the trial.

Funding: This work was supported by Zon-mW the Netherlands grant number 171102007.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The medical ethical committees of all participating hospitals in the Netherlands and Italy approved this study. Maastricht University Medical Centre.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Trial status: The IDEAL DVT study is currently in progress. Patient recruitment started 15 March 2011 and is still ongoing.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Karina Meijer, Saskia Middeldorp, Michiel Coppens, Mandy N Lauw, Y Whitney Cheung, Guy JM Mostard, Asiong Jie, Simone M van den Heiligenberg, Lidwine W Tick, Marten R Nijziel, Marije ten Wolde, Sanne van Wissen, Wim E Terpstra, Marlène HW van de Poel, Hans-Martin Otten, Erik H Serné, Edith H Klappe, Mirian CH Janssen, Tjerk de Nijs, Paolo Prandoni, and Sabina Villalta

References

- 1.Kahn SR, Shrier I, Julian JA, et al. Determinants and time course of the postthrombotic syndrome after acute deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:698–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pesavento R, Villalta S, Prandoni P. The postthrombotic syndrome. Intern Emerg Med 2010;5:185–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prandoni P, Kahn SR. Post-thrombotic syndrome: prevalence, prognostication and need for progress. Br J Haematol 2009;145:286–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prandoni P, Villalta S, Bagatella P, et al. The clinical course of deep-vein thrombosis. Prospective long-term follow-up of 528 symptomatic patients. Haematologica 1997;82:423–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergqvist D, Jendteg S, Johansen L, et al. Cost of long-term complications of deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremities: an analysis of a defined patient population in Sweden. Ann Intern Med 1997;126:454–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandjes DP, Buller HR, Heijboer H, et al. Randomised trial of effect of compression stockings in patients with symptomatic proximal-vein thrombosis. Lancet 1997;349:759–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al. Below-knee elastic compression stockings to prevent the post-thrombotic syndrome: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2004;141: 249–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ten Cate-Hoek AJ, Ten Cate H, Tordoir J, et al. Individually tailored duration of elastic compression therapy in relation to incidence of the postthrombotic syndrome. J Vasc Surg 2010;52:132–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ginsberg JS, Hirsh J, Julian J, et al. Prevention and treatment of postphlebitic syndrome: results of a 3-part study. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:2105–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aschwanden M, Jeanneret C, Koller MT, et al. Effect of prolonged treatment with compression stockings to prevent post-thrombotic sequelae: a randomized controlled trial. J Vasc Surg 2008;47:1015–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn SR, Shapiro S, Wells PS, et al. Compression stockings to prevent post-thrombotic syndrome: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:880–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, et al. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1055–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 1996;37:53–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahn SR, Lamping DL, Ducruet T, et al. VEINES-QOL/Sym questionnaire was a reliable and valid disease-specific quality of life measure for deep venous thrombosis. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:1049–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brouwer W. Handleiding voor het gebruik van PRODISQ versie 2.1 (PROductivity and DISease Questionnaire). Een modulaire vragenlijst over de relatie tussen ziekte en productiviteitskosten. Toepasbaar bij economische evaluaties van gezondheidszorgprogramma's voor patiënten en werknemers. Rotterdam/Maastricht 2004.

- 16.Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Bernardi E, et al. The diagnostic value of compression ultrasonography in patients with suspected recurrent deep vein thrombosis. Thromb Haemost 2002;88:402–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lancaster K. A new approach to consumer theory. J Polit Econ 1966(74):132–57 [Google Scholar]

- 18.CBO. CBO Richtlijn Diagnostiek, preventie en behandeling van veneuze trombo-embolie en secundaire preventie van arteriele trombose. Utrecht: Kwaliteitsinstituut voor de Gezondheidszorg CBO, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirsh J, Guyatt G, Albers GW, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th edition). Chest 2008;133(6 Suppl):110S–12S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blattler W. Aspects of cost effectiveness in therapy of acute leg/pelvic vein thrombosis. Wien Med Wochenschr 1999;149:61–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelderblom GJ, Hagedoorn-Meuwissen EAV. Kousen uittrekhulpmiddel Easy-Lever. Een onderzoek naar bruikbaarheid, effecten en belemmeringen, in opdracht van ZonMw. 2005(juni)

- 22.Raju S, Hollis K, Neglen P. Use of compression stockings in chronic venous disease: patient compliance and efficacy. Ann Vasc Surg 2007;21:790–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villalta S, Bagatella P, Picolli A, et al. Assessment of validity and reproducibility of a clinical scale for the post thrombotic syndrome. Haemostasis 1994(24):158a [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahn SR, Partsch H, Vedantham S, et al. Definition of post-thrombotic syndrome of the leg for use in clinical investigations: a recommendation for standardization. J Thromb Haemost 2009;7:879–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinstein MC, O'Brien B, Hornberger J, et al. Principles of good practice for decision analytic modeling in health-care evaluation: report of the ISPOR Task Force on Good Research Practices—modeling studies. Value Health 2003;6:9–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ten Cate-Hoek AJ, Toll DB, Buller HR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of ruling out deep venous thrombosis in primary care versus care as usual. J Thromb Haemost 2009;7:2042–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ 2002;21:271–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care 1997;35:1095–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blackwelder WC. “Proving the null hypothesis” in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1982;3:345–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laster LL, Johnson MF. Non-inferiority trials: the ‘at least as good as’ criterion. Stat Med 2003;22:187–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.