Abstract

Francisella tularensis is a Gram-negative bacterium responsible for the human disease tularemia. The Francisella pathogenicity island (FPI) encodes a secretion system related to type VI secretion systems (T6SS) which allows F. tularensis to escape the phagosome and replicate within the cytosol of infected macrophages and ultimately cause disease. A lipoprotein is typically found encoded within T6SS gene clusters and is believed to anchor portions of the secretion apparatus to the outer membrane. We show that the FPI protein IglE is a lipoprotein that incorporates 3H-palmitate and localizes to the outer membrane. A C22G IglE mutant failed to be lipidated and failed to localize to the outer membrane, consistent with C22 being the site of lipidation. Francisella tularensis ssp. novicida expressing IglE C22G is defective for replication in macrophages and unable to cause disease in mice. Bacterial two-hybrid analysis demonstrated that IglE interacts with the C-terminal portion of the FPI inner membrane protein PdpB, and PhoA fusion analysis indicated the PdpB C-terminus is located within the periplasm. We predict this interaction facilitates channel formation to allow secretion through this system.

Keywords: tularemia, lipoprotein, intramacrophage, virulence

Introduction

Francisella tularensis is a Gram-negative facultative intracellular bacterium that causes the disease tularemia in humans (Oyston, 2008). Tularemia is usually spread by blood-sucking vectors or is acquired through contact with an infected animal, but it can also be acquired through inhalation. Francisella tularensis has a low infectious dose and high morbidity/mortality associated with pulmonary infections, which has led to its designation as a category A biothreat agent. Different subspecies of F tularensis exhibit different levels of virulence in humans, with F tularensis ssp. tularensis causing the most serious infections and F tularensis ssp. novicida being considered avirulent in healthy humans [depending on classification, F tularensis ssp. novicida is also classified as a separate species, F novicida] (Sjostedt, 2007; Titball & Petrosino, 2007). Francisella tularensis ssp. tularensis has two identical copies of the Francisella pathogenicity island (FPI), whereas F tularensis ssp. novicida has only a single copy of the FPI (Nano et al., 2004; Larsson et al., 2005), but it is not clear whether this difference in FPI copy number contributes to the difference in virulence between these two subspecies.

The FPI is a cluster of 17 genes that are critical for F. tularensis virulence (Nano et al., 2004). The FPI is required for phagosomal escape and replication within the cytosol of infected cells (Golovliov et al., 2003a; Lindgren et al., 2004; Santic et al., 2005). Most of the FPI genes are essential for the virulence of the different subspecies of F. tularensis in mice by various inoculation routes (Golovliov et al., 2003b; Lauriano et al., 2004; Weiss et al., 2007). The FPI encodes a Type VI-like Secretion System (T6SS) that facilitates F. tularensis phagosome escape (Barker et al., 2009; de Bruin et al., 2011;Broms et al., 2012a). T6SS use a phage tail-like injectisome to secrete effector proteins from the bacterial cytoplasm into the cytosol of host cells or other bacteria (Mougous et al., 2006; Pukatzki et al., 2006; Hood et al., 2010; MacIntyre et al., 2010; Basler et al., 2012). In the best-studied T6SS in Vibrio cholerae, a dynamic tubular structure attached to the membrane has been visualized that assembles, contracts, and disassembles within the bacterial cytoplasm to facilitate translocation of proteins out of the cell (Basler et al., 2012).

The secretion system encoded within the FPI has a number of similarities with other T6SS, including the following: (1) IglA and IglB, two interacting proteins that are homologues of the components that constitute the contractile sheath (VipA and VipB) (Bonemann et al., 2009; Broms et al., 2009; Karna et al., 2010); (2). PdpB (IcmF) and DotU, homologues of inner membrane proteins that are required for T6S (Barker et al., 2009; de Bruin et al., 2011; Zheng et al., 2011); and (3). VgrG, a trimeric protein proposed to be loaded onto the tip of the puncturing device and delivered into target cells (Pukatzki et al., 2007; Barker et al., 2009;Broms et al., 2012a). However, the FPI secretion system is also different from well-characterized T6SS in a number of ways, mainly because it appears to be missing components that are considered predictive for a functional T6SS (Boyer et al., 2009). Also, the VgrG protein is significantly smaller and lacks an effector domain typically found in other VgrG proteins, and PdpB/IcmF lacks the Walker A box normally found in these proteins (Zheng & Leung, 2007; Barker et al., 2009), although evidence suggests that the Walker A box is not always critical for T6S (Zheng & Leung, 2007).

Another conserved element of T6SS gene clusters is the presence of a lipoprotein that localizes to the outer membrane (Aschtgen et al., 2008; Boyer et al., 2009). The T6S lipoprotein from Edwardsiella tarda interacts with the C-ter-minus of the inner membrane protein IcmF (Zheng & Leung, 2007), and it has been proposed that this interaction between IcmF in the inner membrane and the lipoprotein in the outer membrane forms a continuous channel spanning the periplasmic space (Leiman et al., 2009). In the current report, we show that the FPI protein IglE is a lipoprotein that localizes to the outer membrane and interacts with PdpB/IcmF. IglE lipidation is required for outer membrane localization, intramacrophage replication, and virulence in mice, consistent with a conserved role of IglE in the T6-like secretion system.

Materials and methods

Strains and media

Francisella tularensis ssp. novicida strains are isogenic with strain U112 (ATCC 15482) and listed in Supporting Information, Table S1. F. tularensis ssp. novicida mutants KKF194 (ΔiglE::ermC) and KKF177 (ΔdotU::ermC) were created using the ‘splicing by overlap extension’ (SOE) method described by Liu et al. (Liu et al., 2007). Escherichia coli strain DH5α was used for cloning (Hanahan, 1983), and KDZif1ΔZ was used for bacterial two-hybrid assays (Vallet-Gely et al., 2005). Luria broth (LB) was used for both liquid medium and agar plates for growth of E. coli strains. F. tularensis ssp. novicida strains were grown on TSAP broth/agar (Liu et al., 2007) or Chamberlain's defined medium (CDM) (Chamberlain, 1965) supplemented with antibiotics, as appropriate. The concentrations of antibiotics used were as follows: ampicillin 100 μg mL−1; tetracycline 15 μg mL−1; kanamycin 50 μg mL−1; erythromycin 150 μg mL−1.

Plasmid construction

A list of plasmids and oligonucleotide primers used in this study can be found in Tables S1 and S2. Restriction sites used in cloning are underlined, and the FLAG tag, C22G mutation, and universal priming sites are noted in bold. Francisella tularensis ssp. novicida U112 genomic DNA was used as template in PCRs. Sequences coding for aa 23–125 of IglE and aa 590–1093 of PdpB were cloned into the bacterial two-hybrid plasmids pKEK1286 and pKEK1287 to form pKEK1542 and pKEK1613, respectively. IglE-FLAG was cloned into pKEK996 (Rodriguez et al., 2008) to form pKEK1355, using primers IglEPciIF and IglEFLAGEcoRIR, and then, site-directed mutagenesis (Novagen) was performed on pKEK1355 with primers IglEC22GF and IglEC22GR to create pKEK1368. The SOE reaction that amplified the ΔiglE::ermC construct in pKEK1063 and the ΔdotU::ermC construct in pKEK1003 used the FTT1346 and FTT1351 primers listed in Table S1 along with the universal primers, as described in (Liu et al., 2007); these plasmids were subsequently transformed into U112 to construct KKF194 (ΔiglE::ermC) and KKF177 (ΔdotU::ermC).

The cyaA sequence in pKEK1069 and pKEK1072 (Barker et al., 2009) was replaced with phoA PCR-amplified with primers PhoAFNdeI and PhoARPstI, to form pKEK1762 (bla-phoA) and ΔN-bla-phoA (pKEK1763), respectively. Sequences coding for aa 1–272 and aa 1–312 of PdpB were cloned into pKEK1762 to construct pKEK1764 and pKEK1765, respectively.

β-galactosidase and alkaline phosphatase assays

For the bacterial two-hybrid assays, plasmids expressing -Zif and -ω fusions were cotransformed into KDZif1ΔZ. Overnight cultures of these strains were diluted 1 : 100 into LB containing 0.3 mM IPTG, grown at 37 °C to OD600 nm 0.2–0.4, and assayed for β-galactosidase activity (Miller, 1992). For alkaline phosphatase assays, F tularensis ssp. novicida strains were transformed with plasmids containing protein phoA fusions listed in Table S1, grown in TSAP supplemented with appropriate antibiotics at 37 °C, and harvested at an optical density of 600 nm of c. 0.3–0.4. Bacterial cells were permeabilized with chloroform and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and assayed for alkaline phosphatase activity by the method described by Michaelis (Michaelis et al., 1983). Statistical significance was determined using Student's t-test.

Protein detection

Fractionation of F tularensis ssp. novicida whole-cell lysates into outer membrane, inner membrane, and cytoplasmic fractions was accomplished using the Sarkosyl membrane fractionation method as adapted by de Bruin et al. (2007). Proteins were detected by separation on a 15% SDS polyacrylamide gel, followed by Western immunoblot using anti-FLAG M2 (Sigma) monoclonal antibody, rabbit polyclonal anti-Tul4 antisera, rabbit polyclonal anti-VgrG, or rabbit polyclonal anti-PdpB [gift from F. Nano; (Ludu et al., 2008)], and ECL detection reagent (Amersham-Pharmacia).

For detection of lipid incorporation into IglE, strains were grown at 37 °C in CDM with [3H]palmitic acid (Moravek Biochemicals) to a final concentration of 20 μCi mL−1. Overnight cultures were pelleted, washed once with PBS, and then resuspended in 1X sample buffer and boiled. Samples were separated by 15% SDS-PAGE and then fixed with 5% glacial acetic acid, 5% isopropanol, and water. The gel was then treated with Autoflour (National Diagnostics) and imaged by autoradiography. Measurement of the labeled protein at 13.2 kD normalized to the label incorporated into a constant band at c. 16 kD in every lane was used to quantitate the relative labeled IglE levels by densitometry of the autoradiograph.

In vivo co-immunoprecipitation

Co-immunoprecipitation experiments were performed similar to those described previously (Felisberto-Rodrigues et al., 2011), with the following modifications. We utilized 250 mL F novicida culture at an OD600 nm of 0.7 as starting material, and the solubilized supernatant was incubated with anti-FLAG antibody coupled to magnetic beads (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at 4 °C.

Intramacrophage assay

Francisella tularensis ssp. novicida strains were used to infect the J774.1 macrophage cell line at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 : 1. The intramacrophage assay was performed as previously described (Lauriano et al., 2003). Statistical significance was determined using Student's t-test.

Mouse virulence assays

Groups of five female 4- to 6-week-old BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories) were inoculated intranasally with F tularensis ssp. novicida strains in 20 μL PBS. Actual bacterial numbers delivered were determined by plate count from inocula, and an c. LD50 nm was determined from surviving mice. Mice were monitored for 30 days after infection. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at UT San Antonio approved all animal procedures.

Results

IglE is a lipoprotein

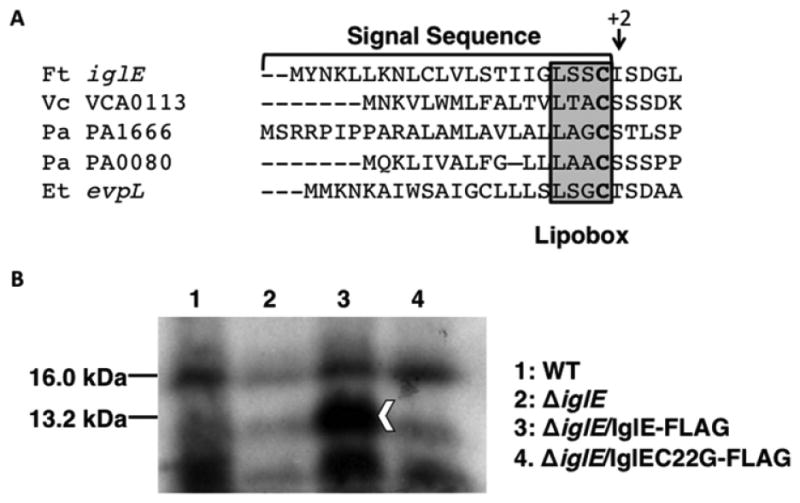

Lipoproteins are synthesized in the cytosol as prolipoproteins with a characteristic leader signal sequence containing a ‘lipobox’ that directs it to the cytoplasmic membrane into the lipoprotein processing pathway. (Okuda & Tokuda, 2011). Processing of the prolipoprotein occurs in three steps in the cytoplasmic membrane, where a cysteine residue immediately downstream of the signal sequence is first modified with diacylglycerol, then the signal sequence is cleaved by signal peptidase II, and finally, the processed protein is N-acylated on the liberated N-terminal cysteine residue (Sankaran & Wu, 1994, 1995). Lipoproteins that subsequently localize to the outer membrane are transported across the periplasmic space by the LolABCDE complex (Okuda & Tokuda, 2011). The LipoP 1.0 Server predicts IglE is cleaved by signal peptidase II between aa 21 and 22 (Juncker et al., 2003), resulting in a mature protein with C22 at the N-terminus available for lipidation, similar to T6SS lipoprotein components found in other bacteria (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

IglE is a lipoprotein. (a) N-terminal sequence of IglE and other T6SS lipoproteins, showing putative lipobox, N-terminal Cys (bold), and +2 residues of mature lipoproteins. (b) 3H-palmitate incorporation into IglE-FLAG. Francisella tularensis ssp. novicida strains U112 (WT; lane 1), KKF194 (ΔiglE; lane 2), and KKF194 carrying pKEK1355 (expresses IglE-FLAG; lane 3) and pKEK1368 (expresses IglEC22G-FLAG; lane 4) were grown in the presence of 3H-palmitate for 24 h. Whole-cell lysates were separated by 15% SDS-PAGE and imaged via autoradiography. Arrowhead indicates location of 3H-labeled IglE-FLAG; 16 kD protein indicated was used for normalization. Quantitation and normalization indicated similar background levels of labeled 13.2-kD protein in lanes 2 and 4, 1.4-fold more labeled protein in lane 1, and 2.9-fold more labeled protein in lane 3.

To determine whether IglE is a lipoprotein, we first created an F. tularensis ssp. novicida strain lacking IglE by deleting the corresponding gene (FTN1311; ΔiglE::ermC; Materials & Methods). Western immunoblot detected expression of the immediate downstream gene product, VgrG, in the iglE mutant strain [Fig. S1; VgrG expression appeared slightly higher in the iglE mutant strain, which may be due to the promoter driving ermC expression (Liu et al., 2007)]. This demonstrates that the ΔiglE::ermC mutation does not prevent expression of the downstream gene within this strain. The ΔiglE F. tularensis ssp. novicida strain was transformed with plasmids expressing either IglE-FLAG, or IglEC22G-FLAG, in which the putative site of lipidation was altered by site-directed mutagenesis to prevent lipidation (C22G). To determine whether IglE is a lipoprotein, the ΔiglE strain alone, or expressing IglE-FLAG or IglE C22G-FLAG was grown in the presence of 3H palmitic acid; the wild-type U112 strain was also grown under similar conditions. Incorporation of 3H palmitic acid is a frequently used technique to identify bacterial lipoproteins and has been used previously to identify F. tularensis Tul4 as an outer membrane lipoprotein (Sjostedt et al., 1991). Whole-cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE, and incorporation of 3H palmitate was visualized by autoradiography (Fig. 1b). Processed IglE-FLAG is predicted to have a molecular mass of 13.2 kD, which corresponds well with the band seen in lane 3, indicating that the IglE-FLAG protein incorporated 3H palmitate. The iglE strain expressing IglE C22G-FLAG protein (lane 4) shows only background labeling, similar to the level seen in the iglE strain without plasmid (lane 2). A very low level of 3H-labeled IglE slightly above background level (1.36-fold) could be detected in the wild-type strain (lane 1); this is likely due to the low natural levels of IglE found in the wild-type strain.

Western immunoblot of these strains with FLAG antibody (Fig. S2) indicated detectable levels of IglEC22G-FLAG expression, and this protein appeared slightly larger than the wild-type IglE-FLAG, consistent with a lack of processing. Prolipoproteins with a Cys residue substitution are localized to the cytoplasmic membrane, but fail to be modified with diacylglycerol, and thus, the signal peptide fails to be cleaved (Sankaran & Wu, 1994); we have seen this phenomenon previously with prolipoproteins from V. cholerae (Morris et al., 2008). This suggests that the lack of palmitate incorporation into IglEC22G is not due to the absence of IglE protein, although there are also lower levels of the unprocessed IglEC22G protein. These results are consistent with IglE being a lipoprotein that is lipidated at C22.

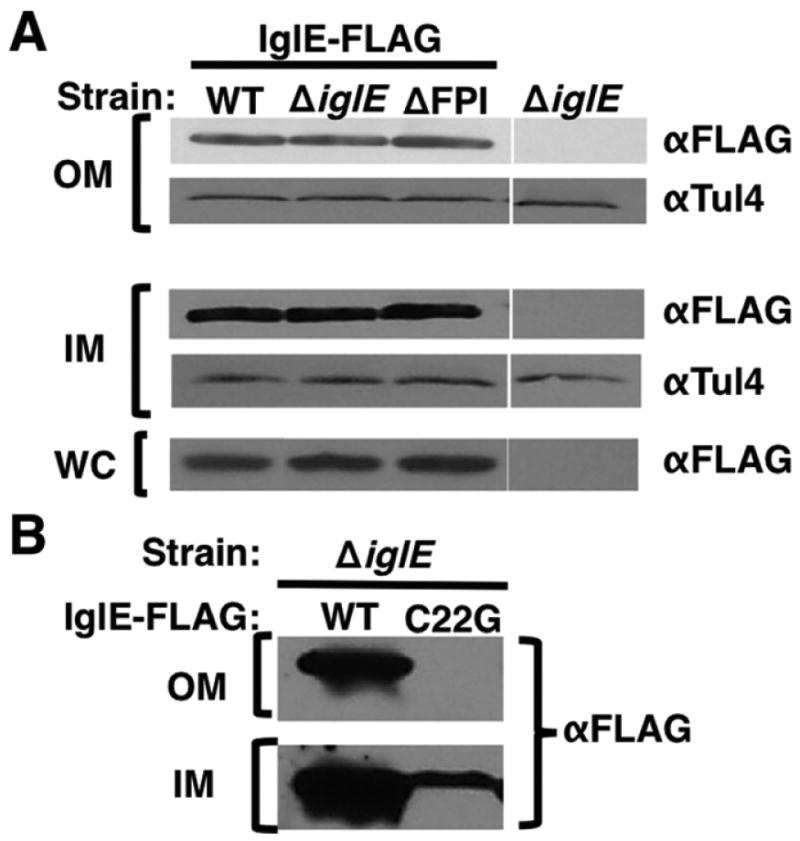

IglE localizes to the outer membrane

IglE is predicted to localize to the OM, because it lacks an Asp at the +2 position (Fig. 1a); an Asp at +2 usually dictates IM rather than OM localization (Okuda & Tokuda, 2011). We examined the localization of IglE by cell fractionation, using F. tularensis ssp. novicida strains expressing IglE-FLAG (Fig. 2a). We utilized both wild type and ΔiglE strains, as well as a strain lacking the entire FPI (ΔFPI), to determine whether other gene products within the FPI affected the localization of IglE. Inner membrane (IM), outer membrane (OM), and whole-cell (WC) samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed by Western immunoblot using anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma), as well as antisera against the F. tularensis lipoprotein Tul4, which is known to localize to the OM (Sjostedt et al., 1990). WC samples were matched to equivalent protein levels, and OM samples were matched to equivalent protein levels. IglE-FLAG could be detected in the OM and IM samples of the wild type and ΔiglE strains, similar to the localization pattern of the known lipoprotein Tul4; because the lipoprotein processing pathway proceeds through the IM, OM lipoproteins can be detected in the IM as well. These results are consistent with IglE localizing to the OM. Also, the fractionation pattern of IglE-FLAG was the same in the strain lacking the entire FPI, indicating that IglE OM localization does not require any of the other FPI proteins.

Fig. 2.

IglE localizes to the outer membrane. (a) Fractionation of IglE-FLAG. Bacterial pellets (‘WC’) and enriched inner membrane (‘IM’) and outer membrane (‘OM’) fractions were prepared from Francisella tularensis ssp. novicida strain U112 (WT), KKF194 (ΔiglE), and KKF219 (ΔFPI) carrying pKEK1355 (expresses IglE-FLAG), or without plasmid. Samples were separated by PAGE and subjected to Western immunoblot analysis with anti-FLAG (‘α-FLAG’) and anti-Tul4 (‘α-Tul4’) antibodies. (b) IglEC22G fails to localize to OM. Enriched inner membrane (‘IM’) and outer membrane (‘OM’) fractions were prepared from F. tularensis ssp. novicida strain KKF194 (ΔiglE) carrying pKEK1355 (expresses IglE-FLAG; ‘WT’) or pKEK1368 (expresses IglEC22G-FLAG; ‘C22G’). Samples were separated by PAGE and subjected to Western immunoblot analysis with anti-FLAG (‘α-FLAG’) antibodies. These are representative blots from at least three independent experiments.

As shown above, the IglEC22G-FLAG protein is not lipidated. To determine whether lipidation of IglE is required for OM localization, we fractionated the ΔiglE strain expressing IglE-FLAG or IglEC22G-FLAG and performed Western immunoblot on the OM and IM fractions using anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 2b). As expected, the IglEC22G-FLAG protein failed to localize to the OM, unlike the IglE-FLAG protein, consistent with lipidation being required for IglE OM localization. Less IglEC22G-FLAG was detected in the IM fraction, compared to the IglE-FLAG protein, and the IM-localized IglEC22G-FLAG protein appeared slightly larger than IglE-FLAG. These results can be explained by the lack of lipoprotein processing caused by the C22G mutation resulting in the pro-lipoprotein being trapped in the IM and degraded (Morris et al., 2008).

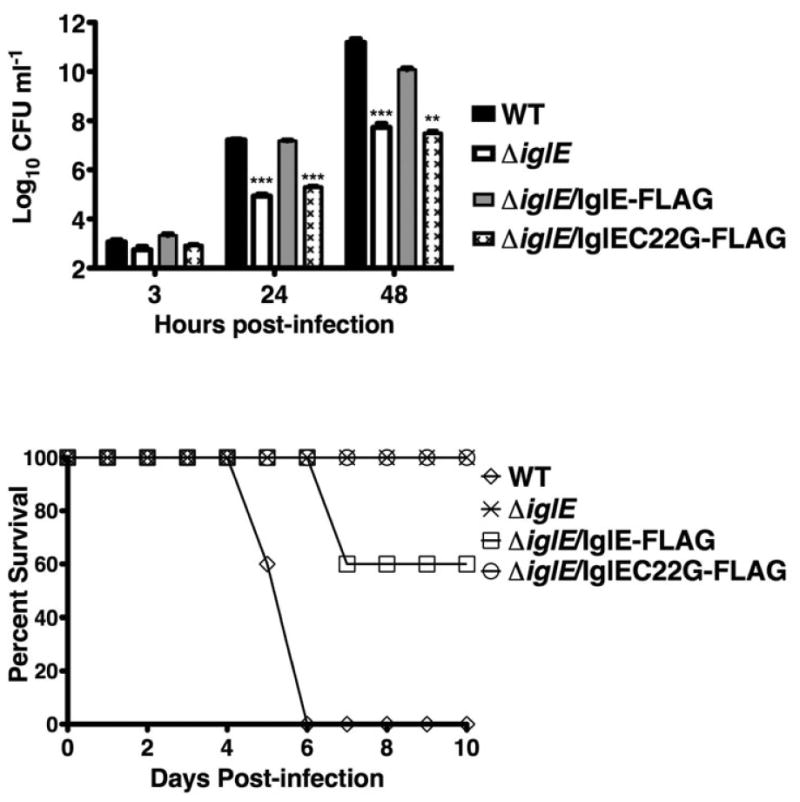

Lipidation of IglE contributes to intramacrophage replication

Intramacrophage replication is a critical virulence attribute of F. tularensis and is dependent upon phagosomal escape. To determine the role of IglE in F. tularensis intramacrophage replication, the ΔiglE strain was examined for growth within the J774 macrophage cell line (Fig. 3). The ΔiglE strain was defective for intramacrophage replication, exhibiting lower levels of intracellular bacteria 24 and 48 h postinfection, in comparison with the wild-type strain U112, which replicates to high intracellular levels during this time period. Notably, the ΔiglE strain was not completely unable to replicate within macrophages, but rather showed a 2–3 log decrease in intracellular bacteria at 24 and 48 h postinfection. This limited intramacrophage growth phenotype is in contrast to other FPI mutants (e.g. vgrG, iglC) that show no intracellular replication over the same time course (Barker et al., 2009). The intracellular growth defect of the iglE strain was overcome by expression of IglE-FLAG in trans, indicating that FLAG-tagged IglE maintains its normal function. However, the intracellular growth defect of the iglE strain was not overcome by expression of IglEC22G-FLAG in trans. These results demonstrate that lipidation of IglE is critical for intramacrophage growth.

Fig. 3.

iglE Francisella tularensis ssp. novicida is defective for intra-macrophage replication. Francisella tularensis ssp. novicida strains U112 (WT) and KKF194 (ΔiglE) either without plasmid or carrying plasmids pKEK1355 (expresses IglE-FLAG) or pKEK1368 (expresses IglEC22G-FLAG) were inoculated at an MOI of c. 10 : 1 into J774 cells, and intracellular bacteria were enumerated at 3, 24, and 48 h. The assay was performed in triplicate. **P < 0.01;***P < 0.001.

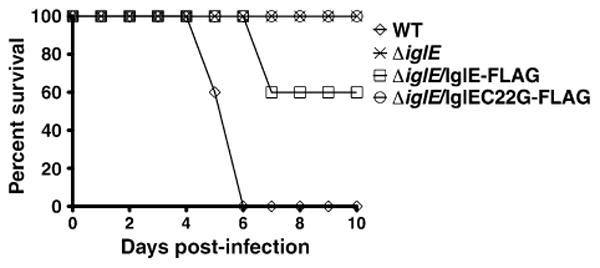

Lipidation of IglE is required for virulence in mice

Previously, transposon mutants with insertions in iglE were identified as being defective for virulence using assays screening for organ dissemination following subcutaneous injection in mice (Weiss et al., 2007) or disease in fruit flies (Ahlund et al., 2010). To determine the role of IglE in F. tularensis virulence in mice via the pulmonary route, the ΔiglE F. tularensis ssp. novicida strain and the ΔiglE strain expressing either IglE-FLAG or IglEC22G-FLAG were inoculated into BALB/c mice intranasally at a relatively high inoculum (c. 105 CFU) and survival monitored (Fig. 4). The wild-type U112 strain was also inoculated into BALB/c mice for comparison. A relatively low inoculum (c. 102 CFU) was utilized for the wild-type strain, due to the low LD50 nm for the wild-type strain via this route. The ΔiglE strain was highly attenuated, causing no mortality at this inoculum. The ΔiglE strain expressing IglE-FLAG showed some restoration of virulence, causing 40% mortality at this inoculum. In contrast, the ΔiglE strain expressing IglEC22G-FLAG was highly attenuated, causing no mortality at this inoculum.

Fig. 4.

iglE Francisella tularensis ssp. novicida is attenuated for virulence in mice. Francisella tularensis ssp. novicida strains U112 (WT) or KKF194 (ΔiglE) either without plasmid or carrying plasmids pKEK1355 (expresses IglE-FLAG) or pKEK1368 (expresses IglEC22G-FLAG) were inoculated intranasally into groups of 5 female BALB/C mice and survival monitored. Inocula used were WT (120 CFU), ΔiglE (1.1 × 105 CFU), ΔiglE/IglE-FLAG (1.2 Δ 105 CFU), and ΔiglE/IglEC22G-FLAG (1.2 × 105 CFU).

The fact that IglE-FLAG expression from the plasmid was able to completely restore intramacrophage replication (above), but not mouse virulence is likely due to the heterologous promoter driving IglE expression, and/or the high copy nature of the complementing plasmid, both of which can lead to incorrect IglE stoichiometry. Nonoptimal amounts of IglE may compromise some aspect of virulence outside of macrophages. Still, the restoration of virulence by IglE-FLAG demonstrates that the attenuated virulence of the ΔiglE strain is specifically due to lack of IglE. As a comparison, the wild-type strain caused the death of all animals at relatively low inoculum by 6 days postinoculation. These results demonstrate a requirement for IglE lipidation for F. tularensis virulence.

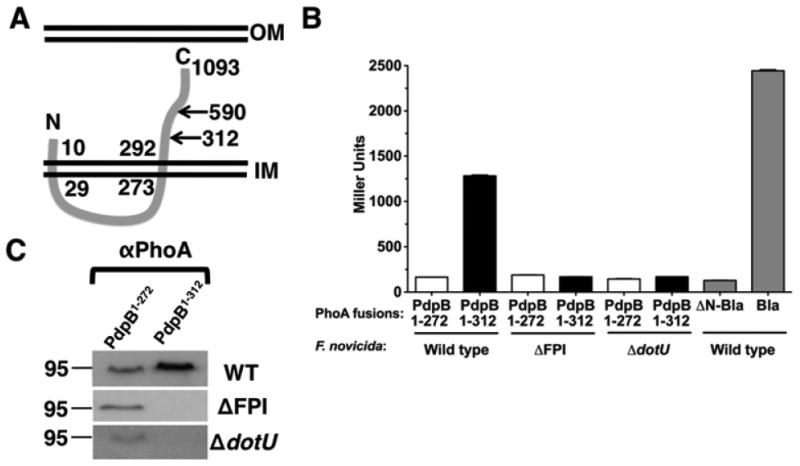

The C-terminus of PdpB is localized in the periplasm

PdpB (IcmF) has previously been shown to be an IM protein (de Bruin et al., 2011), consistent with the localization of IcmF homologues in T6SS. The transmembrane prediction algorithm TMHMM (Krogh et al., 2001) predicts two trans-membrane segments of PdpB, aa 10–29 and aa 273–292 (Fig. 5a). The orientation of the second transmembrane segment determines whether the PdpB C-terminus (aa 293– 1093) is located within the cytoplasm or the periplasm. To determine the orientation of the PdpB second trans-membrane segment, we utilized PhoA fusion analysis. Protein fusions of PhoA to bacterial IM proteins have been used extensively to determine membrane topology, based on the ability of PhoA to be enzymatically active only in the periplasm and not in the cytoplasm (Manoil & Beckwith, 1986). We fused two different N-terminal portions of PdpB to PhoA, either lacking (aa 1–272) or possessing (aa 1–312) the putative second transmembrane segment. As controls, we used secreted (periplasmic; Bla) and nonsecreted (cytoplasmic; ΔN-Bla) forms of beta-lactamase [i.e. possessing or lacking the N-terminal signal sequence; (Barker et al., 2009)].

Fig. 5.

The PdpB C-terminus is localized to the periplasm. (a) The putative transmembrane domains of PdpB as predicted by TMHMM (aa 10–29 and 273–292). The locations of PhoA fusions and the C-terminal fragment used in two-hybrid analyses are indicated. (b) Francisella tularensis ssp. novicida strains U112 (wild type), KKF219 (DFPI), and KKF177 (ΔdotU) were transformed with pKEK1764 (expresses PdpB1–272-PhoA), pKEK1765 (expresses PdpB1–312-PhoA), pKEK1763 (expresses ΔN-Bla-PhoA), and/or pKEK1762 (expresses Bla-PhoA) and assayed for alkaline phosphatase activity. The assay was performed in triplicate. C. Whole-cell lysates from strains used in (b) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western immunoblot analysis with anti-PhoA (‘α-PhoA’) antibodies.

Expression of aa 1–312 of PdpB fused to PhoA in F. tularensis ssp. novicida (‘wild type’) led to high levels of alkaline phosphatase activity (Fig. 5b), similar to levels seen with the (periplasmic) Bla-PhoA fusion. In contrast, expression of aa 1–272 of PdpB fused to PhoA only resulted in background levels of alkaline phosphatase activity, equivalent to the levels seen with the (cytoplasmic) ΔN-Bla fused to PhoA. These results are consistent with an ‘inside-to-outside’-oriented transmembrane segment (aa 273–292) that localizes the PdpB C-terminus in the periplasm. To determine whether any of the other FPI proteins are important for PdpB localization, the PdpB-PhoA fusions were also expressed in a strain lacking the FPI (ΔFPI). This resulted in a loss of activity of the PdpB1–312-PhoA fusion, suggesting that another FPI protein(s) facilitates PdpB stability and/or localization. It has previously been shown that the FPI inner membrane protein DotU is required for the stability of PdpB (de Bruin et al., 2011), similar to DotU and IcmF homologues found in other T6SS (Ma et al., 2009). The PdpB-PhoA fusions were expressed in a ΔdotU strain, which also resulted in a loss of activity of the PdpB1–312-PhoA fusion, consistent with the stabilizing role of DotU on PdpB.

Western immunoblot analyses confirmed a lack of PdpB1–312-PhoA protein in the strains lacking either DotU or the entire FPI (Fig. 5c). Interestingly, the PdpB1–272-PhoA protein was unaffected by the lack of either DotU or the entire FPI, suggesting that the transmembrane region (aa 272–312) is the target of proteolytic degradation in the absence of DotU.

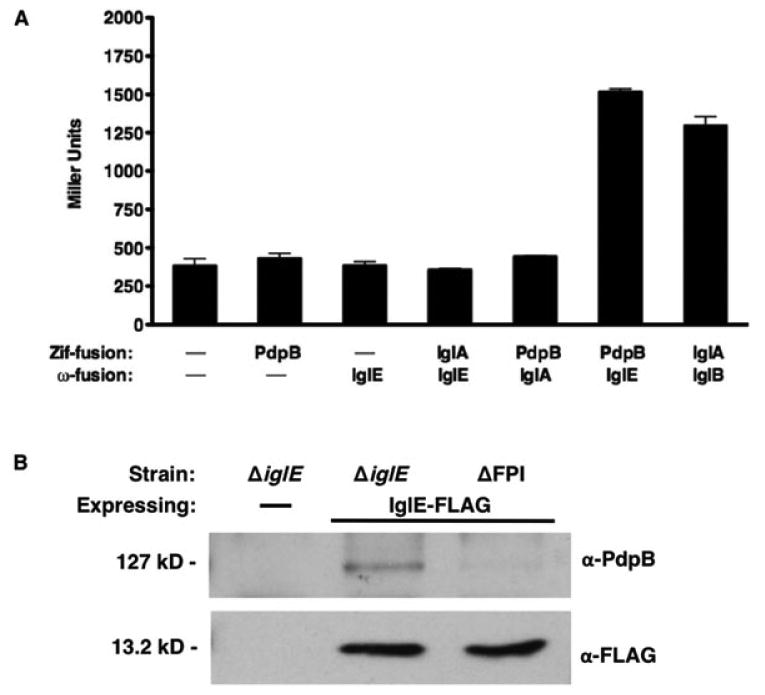

IglE interacts with the C-terminus of PdpB

It has been proposed that interaction between an OM lipoprotein and IcmF in the IM forms a channel spanning the periplasm that is a conserved aspect of T6SS (Leiman et al., 2009; Felisberto-Rodrigues et al., 2011). As determined above, the C-terminal portion of PdpB (IcmF) is located within the periplasm, which would allow for interaction with IglE. To determine whether IglE interacts with the C-terminus of PdpB, we utilized a bacterial two-hybrid system (Dove & Hochschild, 2004; Karna et al., 2010), in which interactions between proteins fused to Zif and ω drive transcription of a lacZ reporter in the E. coli reporter strain KDZif1ΔZ. To prevent secretion outside the cytoplasm, IglE lacking the signal sequence (aa 23–125) was fused to ω, and the C-terminus of PdpB (aa 590–1093) was fused to Zif.

IglE-ω and PdpB-Zif interact and stimulate transcription from the engineered promoter-lacZ fusion present in the KDZif1ΔZ E. coli reporter strain (Fig. 6a). The level of beta-galactosidase activity is higher than that stimulated by the known interaction of IglA-Zif and IglB-ω (Karna et al., 2010), the two FPI proteins that likely compose the contractile sheath. Either plasmid alone is insufficient to stimulate beta-galactosidase activity above background, or neither IglE-ω nor PdpB-Zif interact with another FPI protein, IglA, demonstrating the specificity of interaction.

Fig. 6.

IglE interacts with the PdpB C-terminus. (a) Escherichia coli reporter strain KDZif1ΔZ was transformed with either empty vectors pACTR-AP-Zif and/or pBRGPω (Karna et al., 2010), plasmids pKEK1613 (PdpB590–1093-Zif), pKEK1254 (IglE23–125-ω), pKEK1416 (IglA-Zif), and pKEK1415 (IglB-ω), and assayed for beta-galactosidase activity. All values are result of triplicate samples, **P < 0.01. (b) Whole-cell lysates from Francisella tularensis ssp. novicida strain KKF194 (ΔiglE) or KKF219 (ΔFPI) either with no plasmid (‘–’) or carrying pKEK1355 (expresses IglE-FLAG) were subjected to immunoprecipitation as described in Materials & Methods with α-FLAG. Samples were separated by PAGE and subjected to Western immunoblot analysis with anti-PdpB or anti-FLAG antibodies.

To confirm the interaction of IglE and PdpB in F. tularensis ssp. novicida in vivo, we expressed IglE-FLAG in either the ΔiglE strain or a ΔFPI strain (lacking PdpB) and subjected the cell lysates to immunoprecipitation with α-FLAG. We utilized conditions similar to a previous study that demonstrated the interaction of the T6SS OM lipoprotein TssJ with the IM IcmF homologue TssM of E. coli (Felisberto-Rodrigues et al., 2011). Immunoprecipitation of IglE-FLAG in the presence of PdpB led to co-precipitation of PdpB (Fig. 6b). Control immunoprecipitations of either IglE-FLAG in the absence of PdpB, or in the presence of PdpB and the absence of IglE-FLAG, did not result in detection of PdpB, demonstrating the specificity of this interaction. Our results are consistent with IglE interacting with the C-terminus of PdpB (IcmF) to facilitate channel formation across the periplasm.

Discussion

The ability of F. tularensis to escape the phagosomal compartment within macrophages is central to the virulence of this bacterium (Golovliov et al., 2003a). The FPI is a cluster of 17 genes that are required for phagosomal escape, intramacrophage replication, and virulence (Nano et al., 2004). The FPI genes encode a secretion system that is clearly related to Type VI secretion systems (T6SS), because of several conserved elements discussed below (Barker et al., 2009). However, there are also a number of differences with other T6SS, making the FPI-encoded secretion system unique among T6SS. In fact, it has been suggested that the FPI does not encode a T6SS, based on homology searches which failed to identify several ‘signature’ proteins normally found in T6SS (Boyer et al., 2009). Our results shown here suggest that a conserved element of T6SS, the periplasm-spanning IcmF-DotU-lipoprotein complex, is maintained in the FPI-encoded secretion system, providing further evidence that the FPI encodes a T6SS, albeit an unusual one.

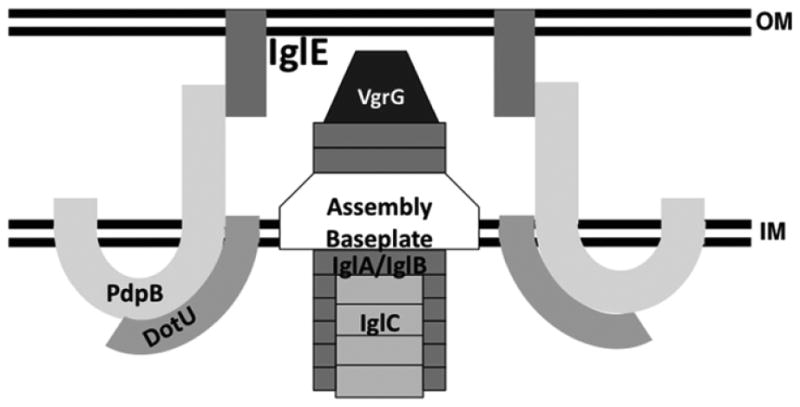

The current model of the ‘typical’ T6SS consists of two subassemblies: an inner- and outer-membrane spanning segment and a contractile bacteriophage tail-like structure (Silverman et al., 2012). The membrane-associated subassembly consists of two integral cytoplasmic membrane proteins, IcmF and DotU. DotU interacts with and stabilizes IcmF, which has a long C-terminal portion that is localized within the periplasm (Ma et al., 2009). The C-terminus of IcmF interacts with a lipoprotein localized to the outer membrane, and it has been proposed that this interaction forms a periplasm-spanning channel that facilitates secretion through the T6SS (Zheng & Leung, 2007; Aschtgen et al., 2008; Felisberto-Rodrigues et al., 2011). The results shown here, along with previous published results, suggest this architecture is conserved in the FPI-encoded secretion system (Fig. 7). The FPI proteins PdpB (IcmF) and DotU are integral inner membrane proteins, and DotU is required for the stability of PdpB (de Bruin et al., 2011). We confirmed this here and further localized the PdpB region targeted for degradation in the absence of DotU to the transmembrane region (aa 272–312). We also showed that the FPI protein IglE is a lipoprotein that localizes to the outer membrane. PhoA fusion analyses demonstrated that the PdpB C-terminus is localized within the periplasm, and two-hybrid and in vivo co-immunoprecipitation analyses showed that the PdpB C-terminus interacts with IglE. Lack of IglE lipidation attenuates intramacrophage replication and virulence, indicating that IglE must be lipidated and anchored in the outer membrane to function. Thus, these interacting FPI components are capable of forming a periplasm-spanning channel that is considered a core component of T6SS.

Fig. 7.

Model of the T6SS encoded by the Francisella tularensis FPI.

The other subassembly present in T6SS is the contractile bacteriophage tail-like structure. The contractile portion within the cytoplasm is a dynamic structure with a sheath composed of two interacting proteins (VipA and VipB in V. cholerae) (Basler et al., 2012) The FPI proteins IglA and IglB are VipA and VipB homologues that have been demonstrated to interact with each other (de Bruin et al., 2007; Broms et al., 2009; Karna et al., 2010). Contraction of the T6SS sheath drives the translocation of a polymer of Hcp loaded with VgrG on its tip across the outer membrane and into either host cells or other bacteria (Pukatzki et al., 2007). The FPI VgrG protein shares homology with other VgrG proteins but is significantly smaller and lacks any associated effector domain normally found in VgrG proteins (Barker et al., 2009). Moreover, no clear homologue of Hcp has been identified within the FPI, although it has been suggested that IglC may serve this function (de Bruin et al., 2011). One of the other differences that distinguishes the FPI secretion system from other T6SS is the lack of any apparent ATPase capability in the ClpV homologue (Barker et al., 2009), which is normally needed for recycling of the VipA/VipB (IglA/IglB) components of the sheath after contraction (Bonemann et al., 2009). Still, evidence has accumulated that the FPI encodes a secretion system (Barker et al., 2009;Broms et al., 2012b) that is related to and shares many characteristics/components with T6SS (de Bruin et al., 2011), and thus, the FPI represents an unusual variant of T6SS, rather than a secretion system distinct from T6SS.

The FPI T6SS is essential for Francisella virulence because it facilitates disruption of the phagosomal membrane and subsequent escape of the bacteria into the cytosol of infected host cells (Lindgren et al., 2004). There is currently no evidence that the FPI T6SS is used for antibacterial interactions, unlike other T6SS (MacIntyre et al., 2010). Perhaps, the unique nature of the FPI T6SS evolved due to its very specific function in phagosomal escape. How phagosome escape is mediated by secretion through the FPI T6SS remains unknown; several potential effectors have been identified, including VgrG, IglC, IglI, and PdpA (Barker et al., 2009;Broms et al., 2012b). Interestingly, IglE was also identified as a secreted protein utilizing a cytosolic β-lactamase reporter assay (Broms et al., 2012b); given that IglE is a lipoprotein localized to the outer membrane, either this localization allows direct access to the reporter in the macrophage cytosol, or this lipoprotein is translocated during the secretion process out of the bacterial outer membrane.

During the preparation of this manuscript, another report was published that confirmed the lipidation and outer membrane localization of IglE in F. tularensis ssp. tularensis and F. tularensis ssp. holarctica LVS (Robertson et al., 2013). These authors suggested that the C-terminus of IglE interacts with some other unidentified protein; our studies extend these observations by demonstrating that IglE interacts with the C-terminus of PdpB. This IglE (lipoprotein)–PdpB/IcmF interaction provides further evidence of the FPI encoding a T6SS.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. The ΔiglE::ermC mutation is not polar on downstream gene expression.

Fig. S2. Detection of IglEC22G-FLAG expression.

Table S1. Plasmids and bacterial strains.

Table S2. Oligonucleotides.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH AI AI57986 and the Army Research Office of the Department of Defense under Contract No. W911NF-11-1-0136.

Footnotes

This article describes an interesting modification of a Francisella virulence protein that contributes to replication within macrophages. They found that lipidation of the Francisella pathogenicity island protein IglE anchors it to the outer membrane where it is involved in facilitating channel formation and thus allowing secretion of other virulence factors.

Supporting Information: Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

References

- Ahlund MK, Ryden P, Sjostedt A, Stoven S. Directed screen of Francisella novicida virulence determinants using Drosophila melanogaster. Infect Immun. 2010;78:3118–3128. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00146-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschtgen MS, Bernard CS, Bentzmann SD, Lloubes R, Cascales E. SciN is an outer membrane lipoprotein required for type VI secretion in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:7523–7531. doi: 10.1128/JB.00945-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker JR, Chong A, Wehrly TD, Yu JJ, Rodriguez SA, Liu J, Celli J, Arulanandam BP, Klose KE. The Francisella tularensis pathogenicity island encodes a secretion system that is required for phagosome escape and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2009;74:1459–1470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06947.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler M, Pilhofer M, Henderson GP, Jensen GJ, Mekalanos JJ. Type VI secretion requires a dynamic contractile phage tail-like structure. Nature. 2012;483:182–186. doi: 10.1038/nature10846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonemann G, Pietrosiuk A, Diemand A, Zentgraf H, Mogk A. Remodelling of VipA/VipB tubules by ClpV-mediated threading is crucial for type VI protein secretion. EMBO J. 2009;28:315–325. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer F, Fichant G, Berthod J, Vandenbrouck Y, Attree I. Dissecting the bacterial type VI secretion system by a genome wide in silico analysis: what can be learned from available microbial genomic resources? BMC Genomics. 2009;10:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broms JE, Lavander M, Sjostedt A. A conserved alpha-helix essential for a type VI secretion-like system of Francisella tularensis. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:2431–2446. doi: 10.1128/JB.01759-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broms JE, Meyer L, Lavander M, Larsson P, Sjostedt A. DotU and VgrG, core components of type VI secretion systems, are essential for Francisella LVS pathogenicity. PLoS One. 2012a;7:e34639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broms JE, Meyer L, Sun K, Lavander M, Sjostedt A. Unique substrates secreted by the Type VI secretion system of Francisella tularensis during intramacrophage infection. PLoS One. 2012b;7:e50473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain RE. Evaluation of live tularemia vaccine prepared in a chemically defined medium. Appl Microbiol. 1965;13:232–235. doi: 10.1128/am.13.2.232-235.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin OM, Ludu JS, Nano FE. The Francisella pathogenicity island protein IglA localizes to the bacterial cytoplasm and is needed for intracellular growth. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin OM, Duplantis BN, Ludu JS, Hare RF, Nix EB, Schmerk CL, Robb CS, Boraston AB, Hueffer K, Nano FE. The biochemical properties of the Francisella pathogenicity island (FPI)-encoded proteins IglA, IglB, IglC, PdpB and DotU suggest roles in type VI secretion. Microbiology. 2011;157:3483–3491. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.052308-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dove SL, Hochschild A. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on transcription activation. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;261:231–246. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-762-9:231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felisberto-Rodrigues C, Durand E, Aschtgen MS, Blangy S, Ortiz-Lombardia M, Douzi B, Cambillau C, Cascales E. Towards a structural comprehension of bacterial type VI secretion systems: characterization of the TssJ-TssM complex of an Escherichia coli pathovar. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002386. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovliov I, Baranov V, Krocova Z, Kovarova H, Sjostedt A. An attenuated strain of the facultative intracellular bacterium Francisella tularensis can escape the phagosome of monocytic cells. Infect Immun. 2003a;71:5940–5950. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5940-5950.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovliov I, Sjostedt A, Mokrievich AN, Pavlov VM. A method for allelic replacement in Francisella tularensis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003b;222:273–280. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:577–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood RD, Singh P, Hsu F, et al. A type VI secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa targets a toxin to bacteria. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juncker AS, Willenbrock H, Von Heijne G, Brunak S, Nielsen H, Krogh A. Prediction of lipoprotein signal peptides in Gram-negative bacteria. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1652–1662. doi: 10.1110/ps.0303703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karna SLR, Zogaj X, Barker JR, Seshu J, Dove SL, Klose KE. A bacterial two-hybrid system that utilizes Gateway cloning for rapid screening of protein-protein interactions. Bio-techniques. 2010;49:831–833. doi: 10.2144/000113539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson P, Oyston PC, Chain P, et al. The complete genome sequence of Francisella tularensis, the causative agent of tularemia. Nat Genet. 2005;37:153–159. doi: 10.1038/ng1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauriano CM, Barker JR, Nano FE, Arulanandam BP, Klose KE. Allelic exchange in Francisella tularensis using PCR products. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;229:195–202. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00820-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauriano CM, Barker JR, Yoon SS, Nano FE, Arulanandam BP, Hassett DJ, Klose KE. MglA regulates transcription of virulence factors necessary for Francisella tularensis intra-amoebae and intra-macrophage survival. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4246–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307690101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiman PG, Basler M, Ramagopal UA, Bonanno JB, Sauder JM, Pukatzki S, Burley SK, Almo SC, Mekalanos JJ. Type VI secretion apparatus and phage tail-associated protein complexes share a common evolutionary origin. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4154–4159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813360106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren H, Golovliov I, Baranov V, Ernst RK, Telepnev M, Sjostedt A. Factors affecting the escape of Francisella tularensis from the phagolysosome. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:953–958. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zogaj X, Barker JR, Klose KE. Construction of targeted insertion mutations in Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida. Biotechniques. 2007;43:487–490. doi: 10.2144/000112574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludu JS, de Bruin OM, Duplantis BN, Schmerk CL, Chou AY, Elkins KL, Nano FE. The Francisella pathogenicity island protein PdpD is required for full virulence and associates with homo-logues of the type VI secretion system. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:4584–4595. doi: 10.1128/JB.00198-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma LS, Lin JS, Lai EM. An IcmF family protein, ImpLM, is an integral inner membrane protein interacting with ImpKL, and its walker a motif is required for type VI Secretion system-mediated Hcp secretion in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:4316–4329. doi: 10.1128/JB.00029-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre DL, Miyata ST, Kitaoka M, Pukatzki S. The Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion system displays antimicrobial properties. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:19520–19524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012931107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoil C, Beckwith J. A Genetic approach to analyzing membrane protein topology. Science. 1986;233:1403–1408. doi: 10.1126/science.3529391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis S, Inouye H, Oliver D, Beckwith J. Mutations that alter the signal sequence of alkaline phosphatase in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:366–374. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.366-374.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JH. A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics. 2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Plainview, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Morris DC, Peng F, Barker JR, Klose KE. Lipidation of an FlrC-dependent protein is required for enhanced intestinal colonization by Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:231–239. doi: 10.1128/JB.00924-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mougous JD, Cuff ME, Raunser S, et al. A virulence locus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a protein secretion apparatus. Science. 2006;312:1526–1530. doi: 10.1126/science.1128393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nano FE, Zhang N, Cowley SC, et al. A Francisella tularensis pathogenicity island required for intramacrophage growth. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:6430–6436. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.19.6430-6436.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda S, Tokuda H. Lipoprotein sorting in bacteria. Ann Rev Microbiol. 2011;65:239–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyston PC. Francisella tularensis: unravelling the secrets of an intracellular pathogen. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:1183–1192. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.2008/000653-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Sturtevant D, Krastins B, Sarracino D, Nelson WC, Heidelberg JF, Mekalanos JJ. Identification of a conserved bacterial protein secretion system in Vibrio cholerae using the Dictyostelium host model system. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1528–1533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510322103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Revel AT, Sturtevant D, Mekalanos JJ. Type VI secretion system translocates a phage tail spike-like protein into target cells where it cross-links actin. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15508–15513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706532104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson GT, Child R, Ingle C, Celli J, Norgard MV. IglE is an outer membrane-associated lipoprotein essential for intracellular survival and murine virulence of type A Francisella tularensis. Infect Immun. 2013;81:4026–4040. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00595-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez SA, Yu JJ, Davis G, Arulanandam BP, Klose KE. Targeted inactivation of Francisella tularensis genes by group II introns. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:2619–2626. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02905-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaran K, Wu HC. Lipid modification of bacterial prolipoprotein. Transfer of diacylglyceryl moiety from phosphatidylglycerol. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19701–19706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaran K, Wu HC. Bacterial prolipoprotein signal peptidase. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santic M, Molmeret M, Klose KE, Jones S, Kwaik YA. The Francisella tularensis pathogenicity island protein IglC and its regulator MglA are essential for modulating phagosome biogenesis and subsequent bacterial escape into the cytoplasm. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:969–979. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JM, Brunet YR, Cascales E, Mougous JD. Structure and regulation of the type VI secretion system. Ann Rev Microbiol. 2012;66:453–472. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-121809-151619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjostedt A. Tularemia: history, epidemiology, pathogen physiology, and clinical manifestations. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1105:1–29. doi: 10.1196/annals.1409.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjostedt A, Sandstrom G, Tarnvik A, Jaurin B. Nucleotide sequence and T cell epitopes of a membrane protein of Francisella tularensis. J Immunol. 1990;145:311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjostedt A, Tarnvik A, Sandstrom G. The T-cell-stimulating 17-kilodalton protein of Francisella tularensis LVS is a lipoprotein. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3163–3168. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3163-3168.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titball R, Petrosino J. Francisella tularensis genomics and proteomics. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1105:98–121. doi: 10.1196/annals.1409.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallet-Gely I, Donovan KE, Fang R, Joung JK, Dove SL. Repression of phase-variable cup gene expression by H-NS-like proteins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11082–11087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502663102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss DS, Brotcke A, Henry T, Margolis JJ, Chan K, Monack DM. In vivo negative selection screen identifies genes required for Francisella virulence. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6037–6042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609675104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Leung KY. Dissection of a type VI secretion system in Edwardsiella tarda. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:1192–1206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Ho B, Mekalanos JJ. Genetic analysis of anti-amoebae and anti-bacterial activities of the type VI secretion system in Vibrio cholerae. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zogaj X, Chakraborty S, Liu J, Thanassi DG, Klose KE. Characterization of the Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida type IV pilus. Microbiology. 2008;154:2139–2150. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/018077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. The ΔiglE::ermC mutation is not polar on downstream gene expression.

Fig. S2. Detection of IglEC22G-FLAG expression.

Table S1. Plasmids and bacterial strains.

Table S2. Oligonucleotides.