Abstract

A hydroxybenzohydrazide-based Schiff base ligand was conveniently synthesized. Upon addition of Zn2+ cation, the ligand exhibited a high tendency to form a binuclear structure with a 2:2 ligand-to-zinc ratio, which was accompanied with a large fluorescence turn-on (λem = 507 nm, ϕfl ≈ 0.28). The reactivity of zinc complex was examined by using different phosphate anions, which reveals a higher response to acid pyrophosphate anion. Detailed spectroscopic studies revealed that the pyrophosphate response is based on the ligand displacement mechanism.

Pyrophosphate ion (PPi) is an important anion, as it is the product of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis under cellular conditions.1 Real-time detection of PPi can be achieved by using the enzymatic method to give bioluminescence,2 which has been used in the commercial pyrosequence for DNA sequence.3 The enzymatic detection of PPi, however, involves a complicate detection scheme by converting PPi to ATP that is then used to generate bioluminescence signal.4 In an effort to search for a simpler detection method, there are significant interests to develop fluorescent chemosensors for PPi in recent years.5,6.

A binuclear core is formed when a chelating ligand holds two metal ions in close distance. Such binuclear cores are commonly found in metallenzymes,7 which are known to play an active role to catalyze the hydrolysis of esters such as phosphates.8 In the binuclear core, two metal centers are positioned closely to each other (with M–M distance of 3–5Ǻ). As a result, the two metal centers in the binuclear core work synergistically to bind a substrate, and the reactivity of one metal center is influenced by the other. The binuclear complexes consisting of Zn(II)–Zn(II) core is also the most commonly used strategy for selective recognition of PPi anion.9–18 Among the known examples, most binuclear complexs have a 1:2 ligand-to-metal ratio. Previous study has demonstrated that the benzoxazole ligand 1 (HL, (λem ~550 nm) tends to form binuclear complex 2 with the Zn(II)–Zn(II) distance of 3.16 Å (λem ~459–478 nm).19 In this study, we report the synthesis of Schiff base 3 which has a similar array of chelating atoms (i.e. N–O–N) as 1 (seen from its complex 2), providing a suitable binding environment for the formation of binuclear Zn(II)–Zn(II) core with a 2:2 ligand-to-metal ratio. In comparison with 1, the ligand 3 contained additional phenolic and carbonyl groups, which provide additional zinc binding strength. Herein we report that the ligand 3 exhibits high tendency to form binuclear Zn(II)–Zn(II) complex 4, giving strong green fluorescence. We then further examined the reactivity of 4 to different phosphate anions, which exhibited good selectivity for hydrogen pyrophosphate H2PPi anion (H2P2O72−), giving large response by turning-off the fluorescence.

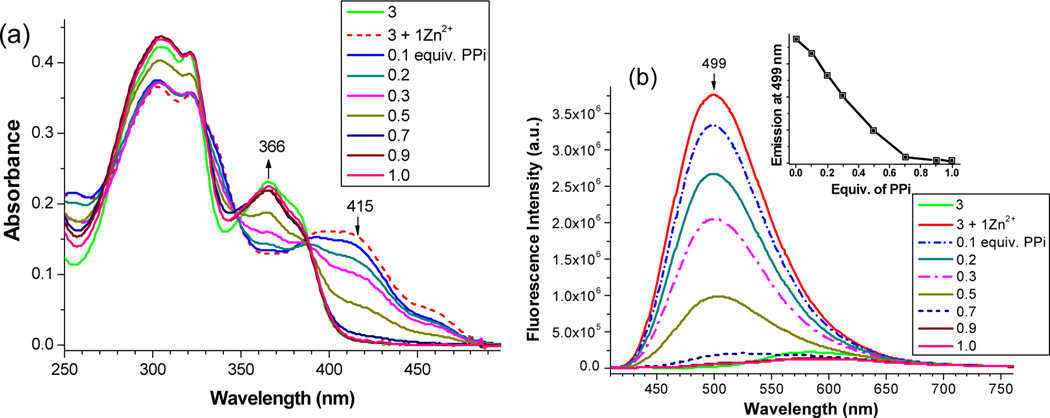

Schiff base ligand 3 was conveniently synthesized by reaction of 2-hydroxy-5-methylisophthalaldehyde with the 2-hydroxybenzohydrazide Ar–CO–NHNH2 in 90% yield by refluxing in ethanol for 2 hrs. In ethanol, the absorption peaks of ligand 3 (at 367 and 382 nm) were gradually decreased upon addition of Zn(NO3)2, which was accompanied with the formation of a new peak at 417 nm (Figure 1a). The observed bathochromic shift, in addition to a clear isobastic point (at 390 nm), indicated the formation of a zinc complex, as a consequence of removing the phenolic proton in 3. Ligand 3 in ethanol was weakly fluorescent (orange in ethanol, λem~576 nm, ϕfl = 0.02). Addition of Zn(OAc)2 (or Zn(NO3)2) to 3 shifted the emission peak to λem = 507 nm (Figure 1b), which was accompanied with a remarkable increase in fluorescence intensity (ϕfl = 0.28). The fluorescence signal was saturated when about 1.2 equiv of Zn2+ was added, suggesting the formation of 1:1 complex. The same crystalline product could be obtained by mixing ligand 3 and Zn(NO3)2 in either 1:1 or 1:2 ratio in DMSO/EtOH (5:1 by volume) solvent, showing the ligand’s strong tendency to form the zinc complex 4 (ESI, Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

UV-vis (a) and fluorescence spectra (b) of ligand 3 (10 µM) in EtOH upon addition of different equiv. of Zn(NO3)2. The inset in (b) shows the fluorescence response to the equiv. of zinc cation.

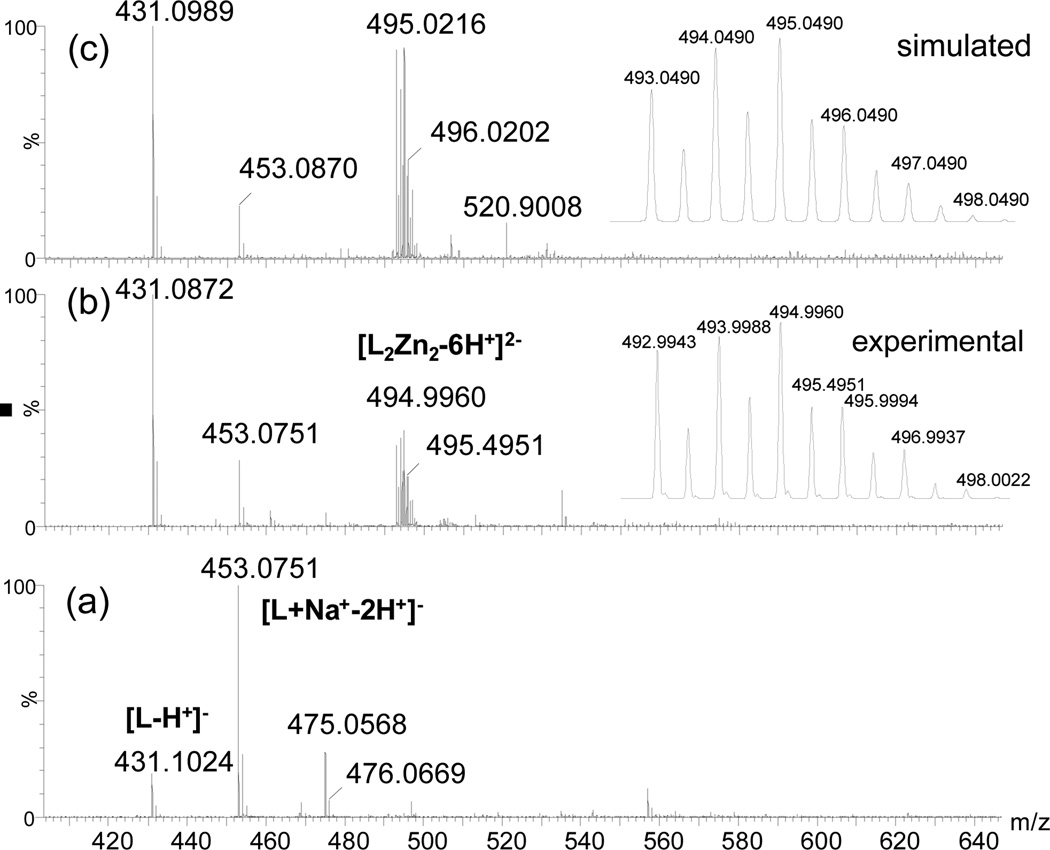

Electronspray mass spectrometry showed that the reaction instantly formed the zinc complex, upon addition of Zn2+ cation to the solution of 3 in anhydrous ethanol (concentration at ~10 µM). The dimer-like complex L2Zn2 was found to be the major product (Figure 2b), whose isotope pattern matched the calculated spectrum for the dianion 4 (C46H34N8O10Zn2, exact mass 986.0981). The crystal sample from “3+Zn” revealed nearly the same mass spectrum pattern (Figure 2c), where the detection of trace ligand indicated that the complexation was reversible. On the basis of detected 2:2 ligand-to-metal ratio, the structure of complex 4 was assumed to be similar to the structure of 2.19 The results clearly indicated that ligand 3 had a high tendency to form the binuclear zinc complex 4. Since the fluorescence response of 3 was saturated when about one equiv. Zn2+ cation was added (Figure 1b), the results consistently suggest that zinc complex 4 (2:2 ligand-to-zinc ratio) was predominant in the solution.

Fig. 2.

ESI-MS spectra of ligand HL 3 (a) in EtOH, upon addition of 0.5 equiv Zn(OAc)2 (b), and crystalline 4 (c). The inset in spectra (b) and (c) are experimental and simulated isotope pattern for mass peak [L2Zn2–6H]2−.

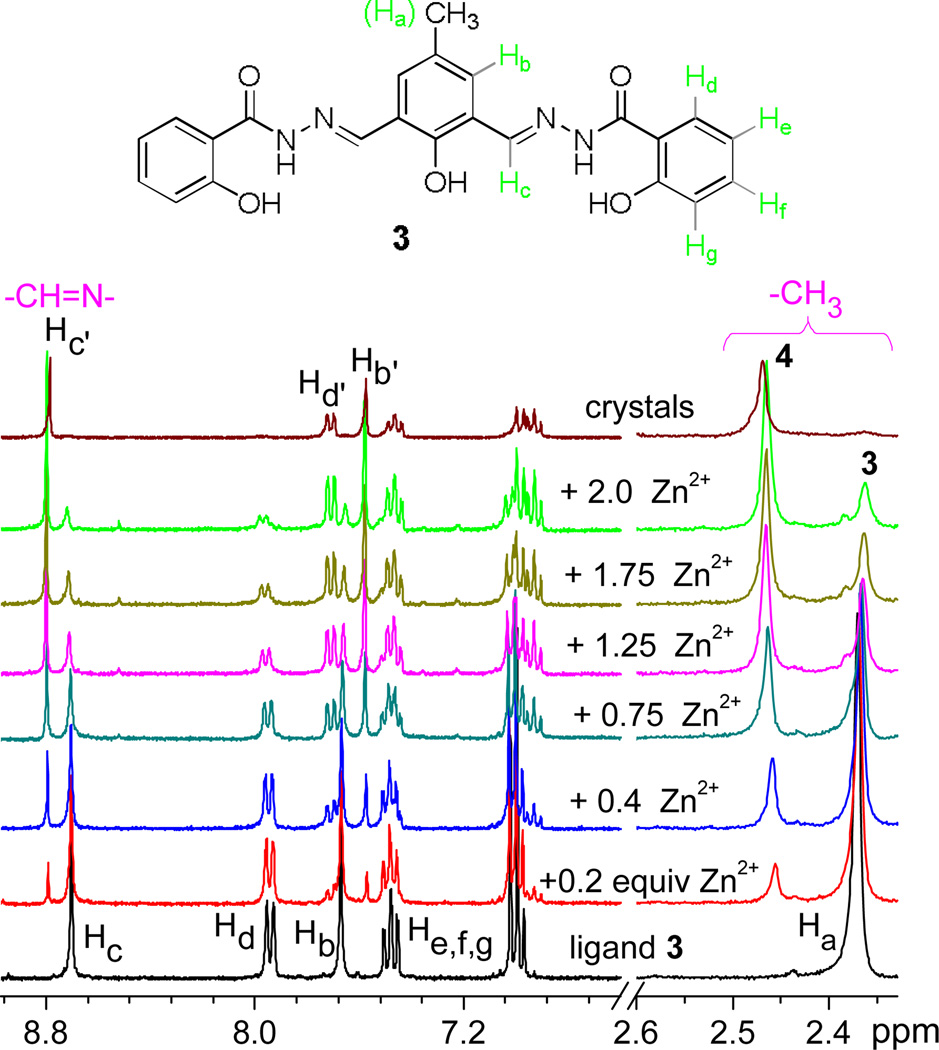

1H NMR titration revealed additional information (Figure 3). When Zn2+ was added, the methyl proton at 2.36 ppm was gradually decreased, which was accompanied with a new signal at 2.46 ppm that was assigned to 4. It appeared that some free ligand 3 was present in the solution even in excess Zn2+ cation at room temperature. The complex 4, however, was relatively stable once it was formed in methanol, as the spectrum of crystal sample of 4 did not show any detectable amount of free 3. Small amount of 3 could be observed when the crystal sample 4 was in DMSO (ESI Figure S2). The observation thus indicated that 4 was predominant in the ethanol solution at room temperature, which is consistent with the finding from the mass study (Figure 2).

Fig. 3.

1H NMR titration of ligand 3 with different equiv. of Zn(NO3)2 in CD3OD/DMSO (5:1 by volume).

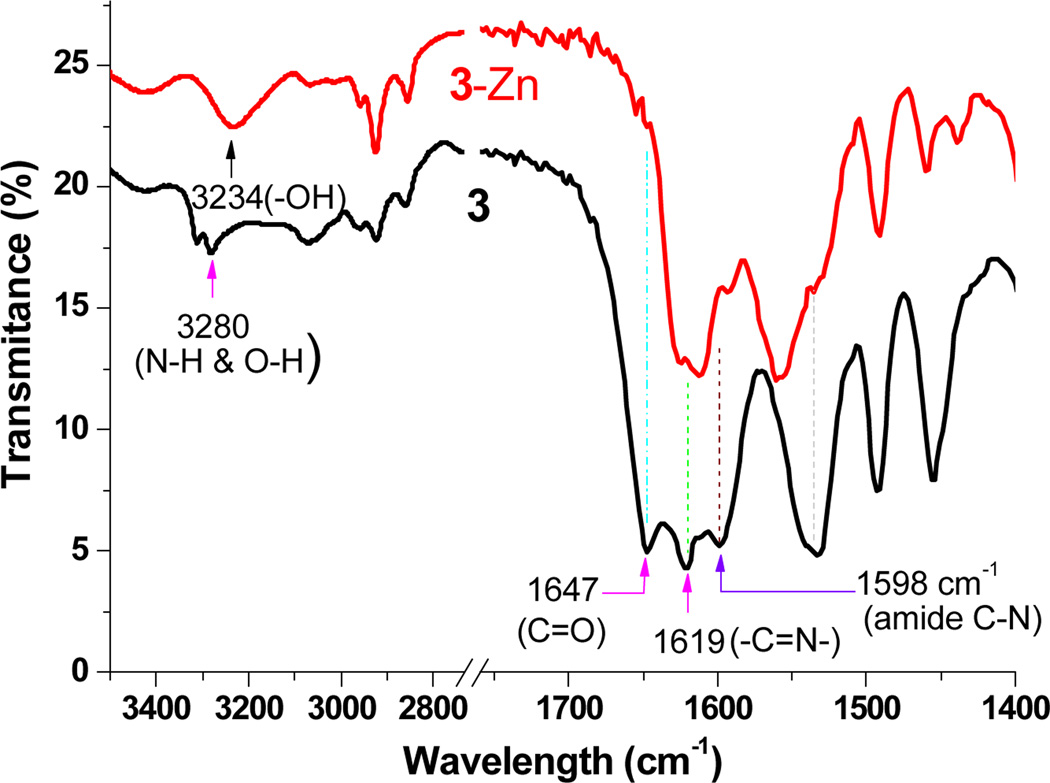

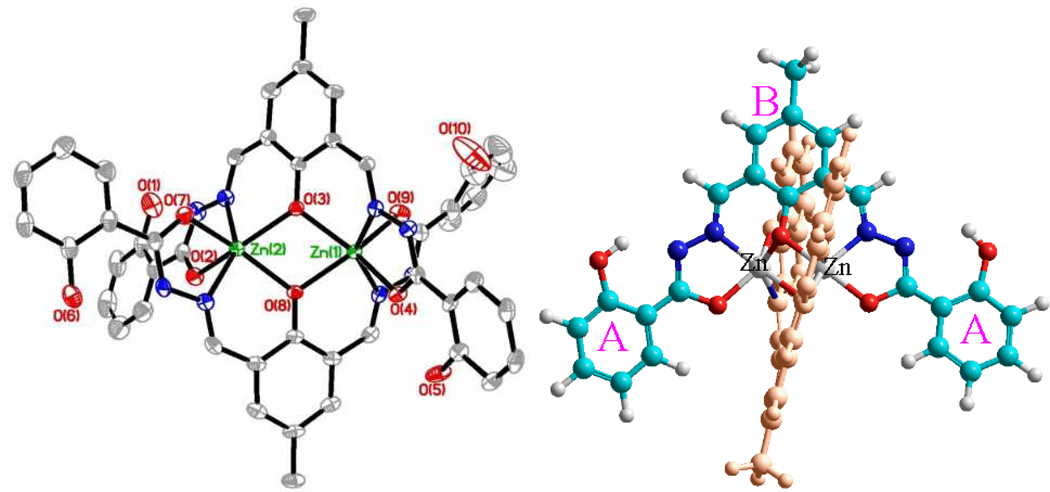

IR spectra for 3 detected the absorption peak at 1619 cm−1 (Figure 4), which is within the stretching frequency (1644-1610 cm−1) for C=N of substituted hydrozone.20 The IR peak at 1647 cm−1 was assigned to aromatic C=O stretching. Complete disappearance of C=O groups in 3-Zn complex indicated the absence of carbonyl group, as a consequence of Zn2+ binding. The observation strongly indicated that the participation of carbonyl in the cation binding, which led us to propose the structure of complex 4, where the amide –C(=O)–NH– group was tautomerized to –C(OH)=N– group. The assumption was supported by disappearance of the strong band at ~1530 cm−1 (from 3), which was characteristic C–N–H stretch-bend for noncyclic monosubstituted amide. IR spectrum of 4 exhibited two C=N bands at 1611 and 1626 cm−1, in agreement with the formation of –C(OH)=N– group. The assumption was also consistent with the 1H NMR, where the doublet signal Hd of 3 at 7.9 ppm was shifted upfield to 7.7 ppm (Figure 3), as a consequence of zinc binding (to carbonyl) that would decrease the electron density of the aromatic ring (less aromatic deshielding effect). Molecular modeling study revealed that the Zn(II)–Zn(II) core in 4 was sandwiched between two ligands and was shielded by two pairs of “end phenols” (marked by A and A’ in Figure 5 & ESI Fig. S18). Following repeated attempts, we finally obtained a good quality crystal whose structure verified that the carbonyl oxygen was connected to the zinc center as proposed in 4. All the evidences thus convincingly pointed to that the binuclear compound 4 with L2Zn2 configuration was formed almost exclusively when ligand 3 reacted with Zn2+ cation. The finding is in sharp contrast to a structural very similar ligand18 where the phenol (not carbonyl) is reported to bind to the zinc cation to give L•Zn2 complex.

Fig. 4.

IR spectra of ligand 3 and 3-Zn complex in KBr. The peak at 1619 cm−1 is attributed to –CH=N– stretching (associated with the substituted hydrozone), while the peak at 1647 cm−1 is to C=O stretching. The strong band at ~1530 cm−1 (from 3) was attributed to characteristic C–N–H stretch-bend for noncyclic monosubstituted amide.

Fig. 5.

Left: Crystal structure of zinc complex 4 shows that the carbonyl oxygen atoms are bonding to zinc. Right: Geometry-optimized structure of 4 by using HyperChem software (molecular mechanics force field MM+), where the C, N, O and Zn atoms are in cyan, blue, red and grey colors, respectively. For clarity, one of the ligand is shown in orange color. The end and central phenyl rings are indicated by letters A and B, respectively.

Response of L2Zn2 Complexes to PPi. Although the zinc complex was formed immediately in alcohol solution, the complex 4 was not stable in pure HEPES buffer (pH = 7.2) (ESI, Figure S3). The sensor response to anions, therefore, was examined in EtOH (Fig. 6 and ESI, Figure S5). UV-vis revealed that the absorption peak at 413 nm was gradually decreasing upon addition of H2PPi (Figure 6a), indicating that the zinc complex was decomposed in ethanol solution. The fluorescence intensity of 4 at ~500 nm was also decreasing upon addition of H2PPi (Figure 6b). The resulting absorption and fluorescence spectra matched the spectra for 3, indicating the release of free ligand 3 from the zinc complex.

Fig. 6.

Fluorescence spectra of zinc complex 4 [prepared from 3 (10 µM) + Zn2+ (10 µM)] in EtOH upon addition of different equivalent of H2PPi.

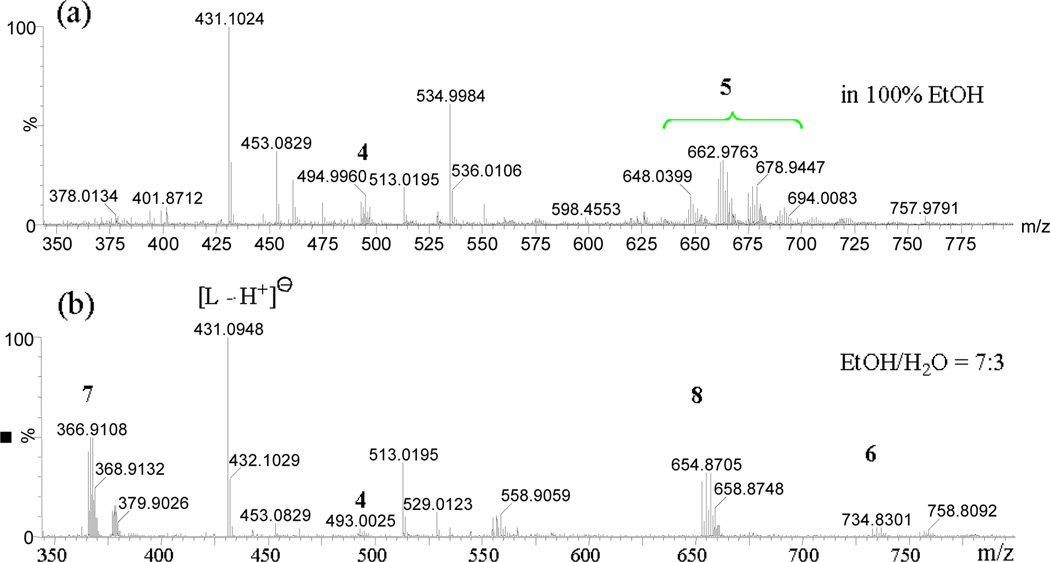

Mass spectrum from the reaction mixture {“3 + Zn(OAc)2” + PPi} in ethanol showed a complicate pattern, which detected not only the free ligand 3, but also zinc complexes 4 and 5 (Figure 7a). It was possible that the reaction of 4 with PPi in ethanol could initially form 6, which could then react with EtOH solvent to give 5. The observed mass isotope patterns 5a (for C27H27N4O7Zn2, exact mass 647.0306), 5b (for C27H25N4O8Zn2, exact mass 661.0255), and 5c (for C27H23N4O9Zn2, exact mass 675.0048) matched the calculated corresponding isotope patterns (ESI Figure S7). The detected 5 was assumed to occur via PPi adduct 6 (Scheme 2), as the binuclear complex 4 was stable in ethanol in the absence of PPi. Interestingly, the presence of 30% water in the reaction mixture greatly simplified the pattern, showing that the zinc complex 4 was almost completely consumed upon addition of one equiv. PPi. The adduct “3 -Zn-PPi” was detected at m/z 732.9058, which matched the isotope pattern of 6 (for C23H19N4O12P2Zn2, exact mass m/z 732.9058) (Figure 7b). The related adduct, dianion 7 (Calcd for C23H18N4O12P2Zn2, exact mass 731.8979), was also observed at m/z 365.9115. In addition, the mass spectrum detected a large peak at m/z 652.8777, which was attributed to 8 (for C23H18N4O9PZn2, exact mass m/z 652.9400) that could be formed via hydrolysis of 6 or 7.

Fig. 7.

ESI-MS spectrum of {“3 +Zn(OAc)2” + H2PPi} in EtOH (a) and EtOH/H2O (7:3 by volume) (b). The anion at m/z 652.8777 was attributed to negatively charged species 8, while the anion at m/z 732.8384 was assigned to 6 (see also ESI, Fig S8–11).

Scheme 2.

A plausible mechanism for the PPi sensor, where interaction of PPi with zinc centers frees the ligand 3 from the complexes.

On the basis of the spectral evidences, a plausible mechanism for the H2PPi sensing, therefore, could be based on the ligand releasing mechanism (Scheme 3). Since the addition of PPi to 4 ca H2used immediate spectral change, we assume that the binding of PPi to 4 released ligand 3 which was weakly fluorescent. Further interaction of 6 with PPi could also release 3, accompanied with formation of Zn2(PPi)2. The assumption was consistent with the detection of 3 and related species 6–8 (Figure 7b).

1H NMR revealed the consistent evidence to support the proposed ligand-releasing mechanism.Addition of two equivalents of Zn2+ shifted most of the imine proton to ~7.80 ppm, indicating that majority of free ligand (at 7.71 ppm) was used to form the zinc complex 3-2Zn (Figure 8). Subsequent addition of H2PPi to the solution of 3-2Zn reduced the population of the Zn2+-bound imine (at ~7.80 ppm), while the population of imine in the free ligand (7.71 ppm) was increasing, clearly indicating that the H2PPi binding event was associated with the release of free ligand. In contrast, addition of ATP to 3-2Zn solution did not cause notable release of ligand 3 (see ESI Figure S13), showing that the complex 3-2Zn was responding selectively to H2PPi.

Fig. 8.

1H NMR titration of [3 + 2Zn2+] in CD3OD with different equiv. of H2PPi.

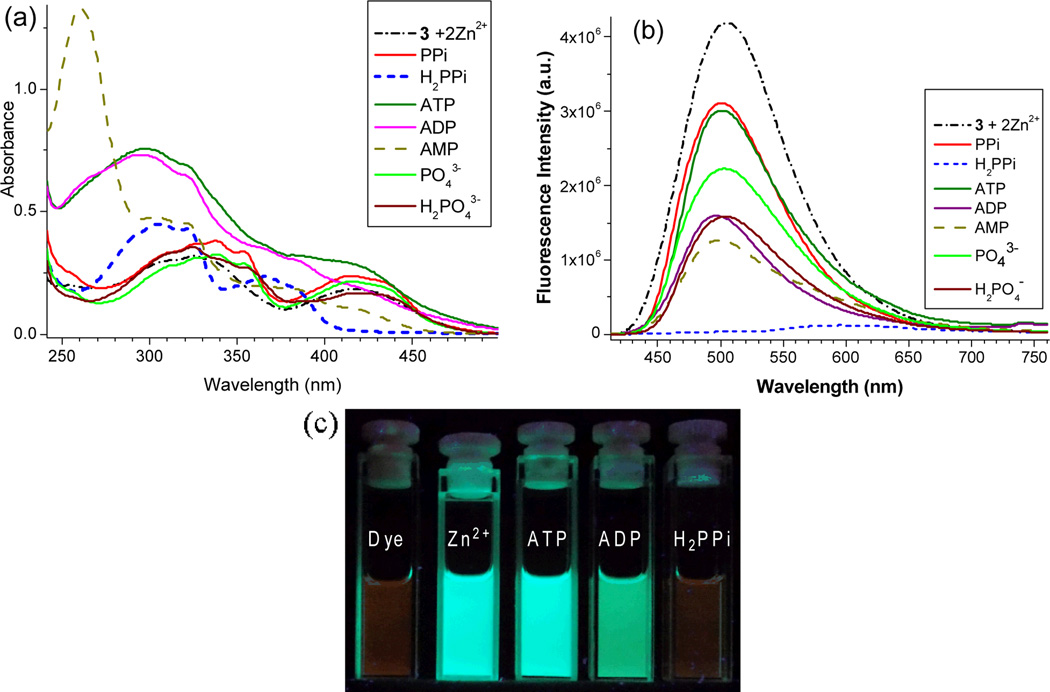

The selective response of sensor was examined by addition of different phosphate anions to the zinc complexes. Among the different phosphate anions used, only H2PPi could completely quench the fluorescence of the zinc complexes (Figure 9). The remarkable selectivity to H2PPi was not simply due to its acidity, as phosphoric acid KH2PO4 did not exhibit the same effect. It appeared that the sensing of H2PPi involves a synergistic interaction of H2PPi with two Zn2+ centers in 4, where two protons are needed to produce each neutral non-fluorescent ligand 3. The sensor’s detection limit for H2PPi was determined to be 2.7×10−9 M (2.7 nM) using D = 3N/S (ESI Figures S14). The fluorescence intensity of 4 exhibited good linear response to H2PPi over a wide concentration range (20 nM – 500 nM) (ESI Figures S15), indicating its potential application.

Fig. 9.

UV-vis (a) and Fluorescence spectra (b) of zinc complex 4 [prepared from 3 (10 µM) + Zn2+ (20 µM)] in EtOH upon addition of different anions (5 equiv). The image (c) shows the fluorescence color changes upon addition of ATP, ADP and H2PPi to the zinc complex (excitation 365 nm).

In conclusion, Schiff base ligand 3 could readily react with Zn2+ to form a binuclear Zn(II)–Zn(II) complexes, giving product 4 (with 2:2 ligand-to-Zn ratio) in solution. Evidences from 1H NMR, IR, and mass spectroscopy are constantly pointing to that the carbonyl of the amide group in the ligand 3 was binding to Zn(II). In the ethanol solution, ligand 3 in ethanol was weakly fluorescent (orange in ethanol, λem~576 nm, ϕfl = 0.02). Addition of Zn(OAc)2 to 3 led to strong green emission (λem = 507 nm, ϕfl = 0.28), which was accompanied with notable spectral shift. The resulting zinc complexes showed intriguing selectively to hydrogen pyrophosphate to turn-off the fluorescence, illustrating its potential for sensor applications. With the aid of mass spectroscopic study, the sensing mechanism was determined to be based on the reaction of complex 4 with pyrophosphate, which led to the release of ligand 3. The study thus provides a simple template and valuable guide for future PPi sensor design.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Structure of ligand 1 and 3, and their zinc complexes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute of Health (Grant No: 1R15EB014546-01A1). We also thank NSF (CHE-1308307) and the Coleman endowment from the University of Akron for partial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Experimental details for synthesis of 3, its 1H and 13C NMR data, and additional absorption and fluorescence spectra for 3 and its zinc complex. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

Notes and references

- 1.Heinonen JK. Biological Role of Inorganic Pyrophosphate. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ronaghi M, Uhlen M, Nyren P. Science. 1998;281:363. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pyrosequencing Protocols. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun Y, Jacobson KB, Golovlev V. Anal. Biochem. 2007;367 doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Neil EJ, Smith BD. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006;250:3068. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ngo HT, Liu X, Jollife KA. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:4928. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35087d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gavrilova AL, Bosnich B. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:349. doi: 10.1021/cr020604g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weston J. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2151. doi: 10.1021/cr020057z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ojida A, Nonaka H, Miyahara Y, Tamaru S, Sada K, Hamachi I. Angew. Chem, Int. Ed. 2006;45:5518. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ojida A, Mito-oka Y, Inoue M, Hamachi I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:6256. doi: 10.1021/ja025761b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee DH, Im JH, Son SU, Chung YK, Hong JI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:7752. doi: 10.1021/ja034689u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ojida A, Mito-oka Y, Sada K, Hamachi I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:2454. doi: 10.1021/ja038277x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonough MJ, Reynolds AJ, Lee WYG, Jolliffe KA. Chem. Commun. 2006;28:2971. doi: 10.1039/b606917g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HN, Xu Z, Kim SK, Swamy KMK, Kim Y, Kim SJ, Yoon J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:3828. doi: 10.1021/ja0700294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhee HW, Lee CR, Cho SH, Song MR, Cashel M, Choy HE, Seok YJ, Hong JI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:784. doi: 10.1021/ja0759139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shin I, Bae SW, Kim H, Hong JI. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:8259. doi: 10.1021/ac1017293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen W, Xing Y, Pang Y. Org. Lett. 2011;13:1262. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anbu S, Kamalraj S, Jayabaskaran C, Mukherjee PS. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:8294. doi: 10.1021/ic4011696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu Q, Medvetz DA, Panzner MJ, Pang Y. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:5254. doi: 10.1039/c000989j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin-Vien D, Colthup NB, Fateley WG, Grasselli JG. The Handbook of Infrared and Raman Characteristic Frequencies of Organic Molecules. Boston: Academic Press, Inc.; 1991. pp. 199–202.pp. 144pp. 208 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.