Abstract

Introduction

Late obstetric emergencies are time critical presentations in the emergency department. Evaluation to ensure the safety of mother and child includes rapid assessment of fetal viability, fetal heart rate (FHR), fetal lie, and estimated gestational age (EGA). Point-of-care (POC) obstetric ultrasound (OBUS) offers the advantage of being able to provide all these measurements. We studied the impact of POC OBUS training on emergency physician (EP) confidence, knowledge, and OBUS skill performance on a live model.

Methods

This is a prospective observational study evaluating an educational intervention we designed, called the BE-SAFE curriculum (BEdside Sonography for the Assessment of the Fetus in Emergencies). Subjects were a convenience sample of EP attendings (N=17) and residents (N=14). Prior to the educational intervention, participants completed a self-assessment survey on their confidence regarding OBUS, and took a pre-test to assess their baseline knowledge of OBUS. They then completed a 3-hour training session consisting of didactic and hands-on education in OBUS. After training, each subject’s time and accuracy of performance of FHR, EGA, and fetal lie was recorded. Post-intervention knowledge tests and confidence surveys were administered. Results were compared with non-parametric t-tests.

Results

Pre- and post-test knowledge assessment scores for previously untrained EPs improved from 65.7% [SD=20.8] to 90% [SD=8.2] (p<0.0007). Self-confidence on a scale of 1–6 improved significantly for identification of FHR, fetal lie, and EGA. After training, the average times for completion of OBUS critical skills were as follows: cardiac activity (9s), FHR (68.6s), fetal lie (28.1s), and EGA (158.1 sec). EGA estimates averaged 28w0d (25w0d-30w6d) for the model’s true gestational age of 27w0d.

Conclusion

After a focused POC OBUS training intervention, the BE-SAFE educational intervention, EPs can accurately and rapidly use ultrasound to determine FHR, fetal lie, and estimate gestational age in mid-late pregnancy.

INTRODUCTION

Goal-directed, focused obstetrical ultrasound (OBUS) is one of the core applications in emergency ultrasound (US). Emergency physician- (EP) performed OBUS is highly accurate in confirming a live intrauterine pregnancy and determining the estimated gestational age (EGA) in the first trimester.1 Additionally, EP- performed early pregnancy OBUS expedites care by decreasing patient length of stay.2,3 While EPs perform first trimester OBUS regularly, third trimester OBUS is performed less often because third trimester emergencies are less frequently encountered in the emergency department.

The rapid evaluation of fetal heart rate (FHR), EGA and fetal lie in third trimester pregnancy is critically important to ensure the well being of both mother and fetus after traumatic injury or during emergent delivery. Historical dating and physical examination of fundal height for gestational age and fetal lie are prone to error.4,5 Point of care US offers the advantage of being able provide the necessary fetal measurements quickly and accurately at the bedside.

Shah et al previously investigated EP-performed OBUS for fetal dating in the third trimester. While EPs are accurate in determining the gestational age in late pregnancy, little is known about the training requirements needed for EPs to achieve competency.6 To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effect of a brief training intervention on the performance by EPs of third trimester OBUS for gestational age, fetal heart rate and fetal lie.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a prospective, observational study of EP accuracy and confidence to perform late pregnancy US after an educational intervention in 2012. Study subjects (EPs) were blinded to the true gestational age and fetal heart rate of the live models used in the training. The study waived informed consent from the university’s institutional review board.

Setting and Subjects

Subjects were a convenience sample of core faculty attending physicians (17) and residents (N=14) from a new academic emergency medicine program in a large urban area in the northwestern United States. 14 of the total 18 residents in the program were present at the didactic session and participated in our study. Resident physicians were grouped into “experienced” residents who had completed a 2 week emergency ultrasound rotation, and “inexperienced” interns who had not yet completed their initial ultrasound rotation. There was also a range of experience with OBUS among the attending faculty, including some who had minimal or no prior training in OBUS, either in residency or subsequently. The study was conducted within a simulation center used for interdisciplinary training.

Intervention

The study intervention was a 3 hour educational module consisting of both lecture and hands-on didactics as part of the resident core curriculum outlined in Table 1. Specifically, 30 minutes of lecture didactics covered a general review of first trimester ultrasound including finding fetal heart rate using M-mode, measurement of crown rump length, and ectopic pregnancy. Lecture didactics in the second 30 minute session covered late pregnancy ultrasound including fetal lie and identification of the fetal head, and fetal biometry including measurement of biparietal diameter (BPD), femur length (FL), head circumference (HC) and abdominal circumference (AC). Emphasis was placed on methods of measuring BPD, highlighting proper landmarks and planes of imaging. The proctored hands-on session was 2 hours long, and subjects received individual instruction from ultrasound fellowship trained EPs at two practice stations with live models in the 2nd and 3rd trimester of pregnancy. Subjects practiced determining fetal biometry, fetal lie, and fetal heart rate using ultrasound. This educational module is called the BE-SAFE curriculum (BEdside Sonography for the Asessment of the Fetus in Emergencies).

Table 1.

Details of the OBUS training course.

| Didactic curriculum for OBUS educational module | Time |

|---|---|

| Mechanics of transabdominal and transvaginal OBUS | 5 minutes |

| Normal US findings in 1st trimester pregnancy | 10 minutes |

| US findings in ectopic pregnancy | 10 minutes |

| Other abnormal US findings in early pregnancy (fetal demise, molar pregnancy) | 10 minutes |

| Determining EGA by CRL | 5 minutes |

| Measuring FHR using M-mode | 5 minutes |

| Fetal biometry in later pregnancy (biparietal diameter, head circumference, abdominal circumference, femur length) | 10 minutes |

| Determination of fetal lie | 5 minutes |

| Hands-on US practice with live models | 120 minutes |

| 1 station TV, non-pregnant | |

| 1 station TA, non-pregnant | |

| 1 station TA, pregnant | |

| 1 testing station TA, pregnant |

OBUS, obstetrical ultrasound; US, ultrasound; EGA, estimated gestational age; CRL, crown-rump length; FHR, fetal heart rate; TV, transvaginal; TA, transabdominal

Study Protocol

Prior to the educational initiative, participating subjects took the obstetric ultrasound quiz at www.emsono.com/acep online and submitted scores to the research assistant. After the BE-SAFE educational initiative, subjects repeated the exam with different questions online using the same website, and submitted their scores for comparison. Before and after the training session, participants also completed an online self-assessment survey of their attitudes regarding, and comfort level with, obstetric ultrasound. They were asked to rate their level of comfort on a scale from 1 (not at all confident) to 6 (very confident) for assessing each of the following using OBUS: FHR, fetal head position (HP), and estimation of gestational age (EGA). Pre- and post- test scores and survey results were compared with descriptive statistics and non-parametric t-tests.

During the hands-on training session after completion of the proctored sessions, each subject was assessed at a final test station where time and accuracy for determining fetal heart rate, BPD, and fetal lie was recorded. Subjects presented individually to the test station and were blind to the fetal lie and true gestational age of a live pregnant model at 27 weeks gestation. Time measures were recorded from probe placement on skin to exact moment of identification of cardiac activity, completion of fetal heart rate measurement using M-mode, and again from probe placement to identification of fetal head and presentation, and to measurement of the biparietal diameter. The research assistant also recorded whether the subject needed verbal cues to complete the required measurements.

Ultrasound Measurements

At the testing and training stations, 3.5MHz curved abdominal transducers and Sonosite Edge US machines (Sonosite Inc., Bothell WA) were used for measurements. M-mode was used for measurement of the fetal heart rate. B-mode imaging was used to measure the fetal biparietal diameter as per standard convention at the level of the falx cerebri and thalamus in an axial plane with calipers placed at the outer aspect of the skull in the near field and the inner aspect of the skull in the far field.

Data Analysis

We conducted an online survey of confidence level, experience, and attitude regarding OBUS for participants both before and after the training, using the Catalyst online web survey tool (Catalyst Web Tools, Solstice Program, University of Washington IT Department, Seattle WA). We analyzed the confidence level results, as well as the pre- and post-knowledge assessment scores from www.emsono.com/acep, using both Kruskal-Wallis Analysis of Variance and Mann-Whitney U tests run using Statistica software (Statistica, StatSoft, Tulsa OK).

RESULTS

31 physicians completed the didactic BE-SAFE training session and a portion of these completed the pre and post tests (N=16) and the pre and post course self assessment survey (N=22). Of the 31 physicians, 14 were residents and 17 were attendings. Pre and post test scores on the knowledge exam provided online by EM Sono and ACEP (www.emsono.com/acep) are shown in Table 2. There was significant improvement (p=0.0007) for untrained physicians from 65.7% (SD=20.8) to an average of 90% (SD=8.16). Previously trained residents had a high pre-test average score of 95% (SD=5), which was maintained with an average post-test score of 95% (SD=7.07). The attending physician group had an average pre-test score of 75.7% (SD=19.89), which improved to an average post-test score of 92.6% (SD=9.78) (p=0.168).

Table 2.

ACEP obstetrical ultrasound test scores.

| Inexperienced residents (SD) | Experienced residents (SD) | Attendings (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-training | 65.71% (20.83) | 95% (5.00) | 75.71% (19.89) |

| Post-training | 90% (8.16) | 95% (7.07) | 92.61% (9.78) |

| p-value | 0.007 | n/a | 0.168 |

ACEP, American College of Emergency Physicians

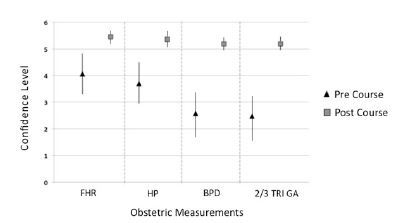

There was significant improvement in physician confidence and overall perception of skill in the self-assessment survey given after the training course. Self-confidence scores for determination of FHR, HP, and EGA, respectively, increased from 4.06 (SD=1.51), 3.69 (SD=1.53), and 2.47 (SD=1.56, to an average of 5.45 (SD=0.51), 5.36 (SD=0.66) and 5.19 (SD=0.6). The self-assessment score change is shown in the Figure.

Figure.

Pre and post course ultrasound confidence assessment. Improvement in confidence levels after the obstetrical ultrasound training course. FHR (fetal heart rate), HP (head position), BPD (biparietal diameter), 2/3 Tri GA (overall use of ultrasound to estimate gestational age in 2nd and 3rd trimester).

During the hands-on testing station, the average times for completion of OBUS critical skills are shown in Table 3. Estimates of gestational age were performed using BPD in 29/31 cases and femur length in 2/31 cases when the fetal head was obscured by the model’s pubic bone. Estimates of gestational age based on obtained measurements averaged 28w0d (25w0d-30w6d, SD 1.36) for the patients’ true gestational age of 27w0d, which is within the conventional +/− 3 week window of error for US measures of gestational age in the third trimester. All participants correctly identified fetal lie as vertex, and accurately measured the FHR at the test station.

Table 3.

Average time to completion of critical OBUS tasks.

| OBUS task | Time |

|---|---|

| Identification of cardiac activity | 9 s |

| FHR measurement by M-mode | 68.6 s |

| Determination of fetal lie | 28.1 s |

| Assessment of gestational age | 158.1 s |

OBUS, obstetrical ultrasound; FHR, fetal heart rate

DISCUSSION

Emergencies in late pregnancy can jeopardize the health of the patient and her fetus, and much of the information needed for optimal patient care may be quickly ascertained using bedside US. Despite this, there is limited published literature regarding EP performance of point-of-care sonography in second- and third-trimester pregnancy. Shah and colleagues6 showed that EPs can accurately estimate late-term gestational age, a finding supported by our results. However, evidence-based guidelines to identify the optimal length and intensity of training in OBUS necessary for EPs to achieve competence are lacking. Our study showed that a brief training module increased EP knowledge of OBUS and improved confidence for the determination of EGA, as well as for the assessment of two additional important clinical data points: fetal lie and heart rate.

Although the utility of US for the detection of maternal injury during pregnancy has been previously demonstrated,7 most of the literature regarding the ability of EPs has been focused on first-trimester complaints. Use of emergency US in pelvic disorders tends to focus on detection of intrauterine pregnancy to rule out ectopic pregnancy. In this setting, EP-performed US has been shown to have high sensitivity and specificity.8,9

Late-term fetal dating and position assessment may be of utility in the setting of shock or trauma, where the patient in extremis may not be able to provide accurate information and the decision for aggressive intervention could be determined by the gestational age of the fetus. Fetal viability begins at a gestational age of approximately 24 weeks,10,11 often estimated by determination of fundal height. Physical diagnosis of fundal height, however, may be limited by body habitus and in the setting of trauma, by uterine rupture, making estimation of age difficult to achieve. Our training module also taught EPs to assess the fundal height by US, though the accuracy of this method was not assessed in our study and warrants future investigation.

Additionally, our study demonstrated that the entire US assessment of FHR, HP, and EGA was completed in under five minutes. When peri-mortem or crash cesarean delivery is being considered, rapid and accurate assessment of gestational age is critical for physicians facing time-sensitive decisions.

LIMITATIONS

Our study has several limitations that we have identified. We note that while a range of both resident and attending physicians with varying levels of ultrasound skills participated in the study, because this is a small convenience sample of physician subjects, the results may not be generalizable to larger audiences of EPs.

In addition, this is a live simulation-based training model, and while physician subjects were largely successful in accurate and rapid ultrasound measurements in this environment, the challenges of ultrasound use in an actual ED environment may affect the performance of these ultrasound exams.

Ultrasound measurements of gestational age in the second and third trimester may be within a 2–3 week range of the true gestational age of a fetus, even when measurements are done perfectly. In light of this fact, any study that seeks to assess accuracy of fetal biometry measurements will need to allow for normal variations in ultrasound measurements.

CONCLUSION

To conclude, we found that EPs can accurately and rapidly estimate gestational age, fetal heart rate and fetal lie in the second and third trimester after the brief BE-SAFE training intervention. This information is of value in the setting of shock or injury during late pregnancy, when the patient cannot communicate their gestational age or in the event of precipitous delivery.

Footnotes

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The preparation of this manuscript was partially supported by W81XWH-10-2-0023 from the Department of Defense U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command to Drs. Fernandez and Shah and 1R18HS020295 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to Dr. Fernandez. The authors disclosed no other potential source of bias.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saul T, Lewiss RE, Rivera MDR. Accuracy of emergency department bedside ultrasound in determining gestational age in first trimester pregnancy. Critical Ultrasound Journal. 2012;4(1):22. doi: 10.1186/2036-7902-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaivas M, Sierzenski P, et al. Do emergency physicians save time when locating a live intrauterine pregnancy with bedside ultrasonography? Academic Emergency Medicine. 2000;7:988–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shih CH. Effect of emergency physician-performed pelvic sonography on length of stay in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29:348–352. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietz PM, et al. A comparison of LMP-based and ultrasound-based estimates of gestational age using linked California livebirth and prenatal screening records. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007;21(Suppl 2):62–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gabbe S, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 5th ed. Chapter 5 Churchill Livingstone; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah S, Teismann N, et al. Accuracy of emergency physicians using ultrasound to determine gestational age in pregnant women. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010;28:834–838. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards JR, Ormsby EL, et al. Blunt abdominal injury in the pregnant patient: detection with US. Radiology. 2004;233(2):463–70. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2332031671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durham B, Lane B, et al. Pelvic ultrasound performed by emergency physicians for the detection of ectopic pregnancy in complicated first-trimester pregnancies. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29(3):338–47. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saul T, Lewiss RE, et al. Accuracy of emergency physician performed bedside ultrasound in determining gestational age in first trimester pregnancy. Crit Ultrasound J. 2012;4(1):22. doi: 10.1186/2036-7902-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grossman NB. Blunt trauma in pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70(7):1303–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown HL. Trauma in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(1):147–60. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ab6014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]