Abstract

Objective To assess the incidence of early stage and advanced stage breast cancer before and after the implementation of mass screening in women aged 70-75 years in the Netherlands in 1998.

Design Prospective nationwide population based study.

Setting National cancer registry, the Netherlands.

Participants Patients aged 70-75 years with a diagnosis of invasive or ductal carcinoma in situ breast cancer between 1995 and 2011 (n=25 414). Incidence rates were calculated using population data from Statistics Netherlands.

Main outcome measure Incidence rates of early stage (I, II, or ductal carcinoma in situ) and advanced stage (III and IV) breast cancer before and after implementation of screening. Hypotheses were formulated before data collection.

Results The incidence of early stage tumours significantly increased after the extension for implementation of screening (248.7 cases per 100 000 women before screening up to 362.9 cases per 100 000 women after implementation of screening, incidence rate ratio 1.46, 95% confidence interval 1.40 to 1.52, P<0.001). However, the incidence of advanced stage breast cancers decreased to a far lesser extent (58.6 cases per 100 000 women before screening to 51.8 cases per 100 000 women after implementation of screening, incidence rate ratio 0.88, 0.81 to 0.97, P<0.001).

Conclusions The extension of the upper age limit to 75 years has only led to a small decrease in incidence of advanced stage breast cancer, while that of early stage tumours has strongly increased.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the largest contributor to cancer incidence and cancer mortality in women worldwide.1 As people in Western societies are living longer, there will be an increase in the proportion of older women with breast cancer in upcoming years.2 Older women with breast cancer often have comorbidities and functional limitations,3 4 resulting in an increased risk of adverse outcomes and side effects from breast cancer treatment.5 6 7 Also, previous studies have shown that breast cancer specific mortality increases with age.8 It has been assumed that diagnosis at an earlier stage through screening programmes could improve the prognosis of breast cancer and may therefore be beneficial for older women.9 Several current guidelines recommend breast cancer screening with mammography for women aged up to 75 years,10 11 and in the Netherlands in 1998, the upper age limit of the mass screening programme was extended from 69 to 75 years.12

However, no strong evidence exists for the beneficial effects of breast cancer screening in older women, as randomised trials on such screening rarely included women over the age of 60 years.9 Although trial data on screening in older women are lacking, some observational studies hint at a beneficial effect on mortality rates in this age group.12 13 14 However, several confounding factors might influence outcomes of population based studies on mortality rates in the older population. For example, it is known that interval detected tumours are generally more aggressive than screen detected tumours,15 which can result in bias. Furthermore, comorbidity and poor physical functioning in older women lead to poor attendance to the screening programme and can therefore result in biased outcomes of these observational studies.16

A more appropriate way to investigate the efficacy of a screening programme in population based data would be to investigate the incidence rates of advanced stage cancers after implementation of a screening programme.17 If a screening programme is effective, it can be expected that the incidence of advanced stage cancer decreases, while the incidence of early stage breast cancer increases.17 This approach is not affected by confounding factors that are often present in observational studies on the effects of screening on mortality rates.17 We assessed the incidence of early stage and advanced stage breast cancer before and after implementation of the mass screening programme in women aged 70-75 years in the Netherlands.

Methods

Study population

This study was designed as a prospective nationwide population based study. From the Netherlands cancer registry we selected all patients aged 70-75 with a diagnosis of invasive and ductal carcinoma in situ breast cancer between 1995 and 2011. The registry contains information on all newly diagnosed malignancies in the Netherlands. Patients are detected through the central pathology database. Trained staff review the charts of all patients with a pathologically confirmed malignancy. To compare changes in incidence rates with incidence rates of breast cancer in the Dutch population in general, we additionally assessed the incidence of breast cancer in patients aged 76-80 years, as they did not undergo routine screening and could therefore be used as a reference population.

Since the Netherlands cancer registry registers anonymous population data, no written informed consent was required.

We used the tumour-node-metastasis (TNM) classification at year of diagnosis to describe tumour stage, with disease T, N, and M stage used. If the disease stage was missing, we used clinical stage for the analyses. We defined early tumour stage as stages I and II and ductal carcinoma in situ disease. Advanced tumour stage was defined as stages III and IV disease.

Statistical analyses

For all analyses we used Stata version 10.0. All statistical tests were two sided and we considered P values <0.05 to be significant.

We calculated national incidence rates by using population data from Statistics Netherlands.18 For each year we derived person years by using the number of women living in the Netherlands. We calculated national incidence rates by dividing the number of incident tumours by the number of female residents of the same age in the Netherlands in the year of diagnosis. Time trends in the incidence of different tumour stages were presented graphically, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

The screening programme was implemented in the Netherlands between 1998 and 2001. In these four years, all eligible women were invited for mammography screening.19 Hence we divided the included years into three periods: a period before screening (1995-97), a screening uptake period of five years to prevent bias from a too short definition of this period (1998-2002), and a period after implementation of screening (2003-11, defined as active screening). We assessed the changes in incidence rates over these three periods by calculating incidence rate ratios using Poisson regression analyses. Additionally, we assessed the change in incidence rates over time in patients aged 76-80 years, to take into account changes in incidence rates in the general older population with breast cancer independent of screening. By dividing the incidence rate ratio of patients aged 70-75 by the incidence rate ratio in the reference population (76-80 years), we calculated the ratio of these two incidence rate ratios, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

To estimate the number of “extra” early stage tumours that were found per “prevented” advanced stage tumour, we calculated the ratio between the observed changes in early stage and advanced stage breast cancer in patients aged 70-75 years.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed several sensitivity analyses. Firstly, to assess the impact of our definition of the screening uptake period on the outcomes we both shortened and lengthened this period (1998-2001 and 1998-2003, respectively). Secondly, to assess the impact of different definitions of early stage breast cancer we excluded from the analyses all patients with stage II disease. Finally, to ensure that we did not miss small changes in incidence rates as a result of loss of power from use of three periods we performed the analyses with year of diagnosis as a continuous variable (starting from 1998) instead of using all three periods.

Results

Patient characteristics

Overall, 25 414 patients aged 70-75 and 13 028 patients aged 76-80 were included from the Dutch cancer registry (table 1). In both age groups most patients had a diagnosis of stage I or stage II breast cancer.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women with a diagnosis of breast cancer in the Netherlands during implementation of screening in women aged 70-75 years, presented per age group. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Diagnosis by age group | Period | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prescreening (1995-97) | Screening uptake (1998-2002) | Active screening (2003-11) | |

| 70-75 years (n=25 414) | |||

| Stage at diagnosis: | |||

| Carcinoma in situ | 156 (4.6) | 718 (9.1) | 1477 (10.5) |

| I | 986 (28.8) | 3346 (42.3) | 6824 (48.5) |

| II | 1632 (47.6) | 2994 (37.8) | 4015 (28.5) |

| III | 371 (10.8) | 472 (6.0) | 1206 (8.6) |

| IV | 283 (8.3) | 381 (4.8) | 553 (3.9) |

| Source population (person years) | 1 115 508 | 1 842 139 | 3 394 055 |

| 76-80 years (n=13 028) | |||

| Stage at diagnosis: | |||

| Carcinoma in situ | 121 (5.5) | 207 (5.0) | 436 (6.5) |

| I | 584 (26.6) | 1058 (25.4) | 1851 (27.7) |

| II | 1038 (47.3) | 2013 (48.4) | 2781 (41.7) |

| III | 243 (11.1) | 434 (10.4) | 1041 (15.2) |

| IV | 210 (9.6) | 449 (10.8) | 589 (8.8) |

| Source population (person years) | 686 507 | 1 282 037 | 2 386 061 |

Time trends in tumour stages

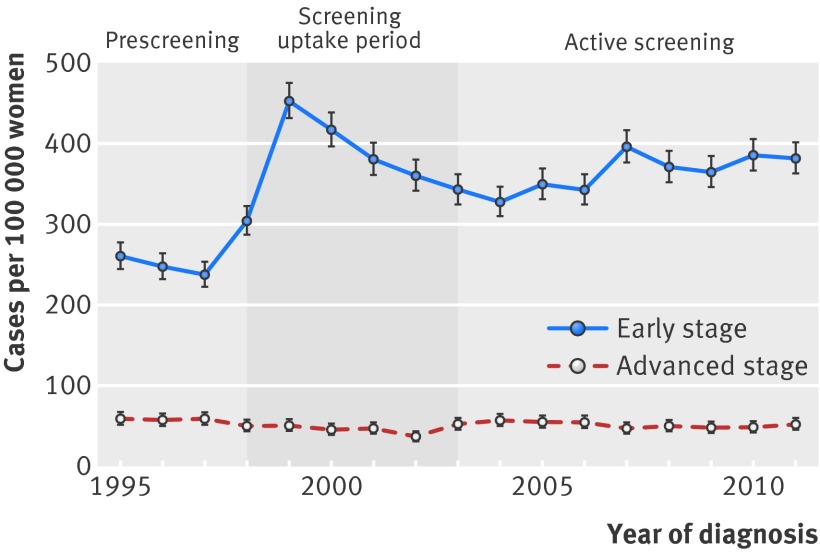

The figure shows the incidence rates of different tumour stages in women aged 70-75 before and during active screening. Table 2 presents the corresponding Poisson regression analyses. The incidence of early stage breast cancer significantly increased after extension of the upper age limit to 75 in 1998 and decreased slightly after 2002, after which the increase of early stage disease continued (248.7 cases per 100 000 women before screening up to 362.9 cases per 100 000 women during active screening, incidence rate ratio 1.46, 95% confidence interval 1.40 to 1.52, P<0.001). This increase was explained by a statistically significant increase in the incidence of ductal carcinoma in situ and stage I tumours; the incidence of both tumour types (combined) more than doubled, from 107 per 100 000 women in 1995 to 274 per 100 000 women in 2011. This increase in incidence rate was not accompanied by a similar decline in stage II tumours, as the incidence of such tumours declined from 154 per 100 000 women in 1995 to 108 per 100 000 women in 2011. Although the incidence of advanced stage breast cancers significantly decreased, the absolute decrease was small (58.6 cases per 100 000 women before screening to 51.8 cases per 100 000 women in the active screening period, incidence rate ratio 0.88, 95% confidence interval 0.81 to 0.97, P<0.001).

Breast cancer incidence in women aged 70-75 years, the Netherlands

Table 2.

Breast cancer incidence before and after implementation of screening in the Netherlands

| Time period | 70-75 years | 76-80 years | Relative ratio (95% CI)† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence* | IRR (95% CI) | P value | Incidence* | IRR (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Early stage: | ||||||||

| Prescreening (1995-97) | 248.7 | 1.0 (ref) | <0.001 | 253.9 | 1.0 (ref) | <0.001 | 1.0 | |

| Screening uptake period (1998-2002) | 383.1 | 1.54 (1.47 to 1.61) | <0.001 | 255.7 | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.06) | 0.81 | 1.52 (1.41 to 1.65) | |

| Active screening (2003-11) | 362.9 | 1.46 (1.40 to 1.52) | <0.001 | 212.4 | 0.84 (0.79 to 0.88) | <0.001 | 1.73 (1.61 to 1.87) | |

| Advanced stage: | ||||||||

| Period: | ||||||||

| Prescreening (1995-97) | 58.6 | 1.0 (ref) | <0.001 | 66.0 | 1.0 (ref) | 0.73 | 1.0 | |

| Screening uptake period (1998-2002) | 46.3 | 0.79 (0.71 to 0.87) | <0.001 | 68.9 | 1.04 (0.94 to 1.17) | 0.46 | 0.76 (0.66 to 0.88) | |

| Active screening (2003-11) | 51.8 | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.97) | 0.007 | 67.2 | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.13) | 0.74 | 0.86 (0.76 to 0.98) | |

IRR=incidence rate ratio.

*Cases per 100 000 women per year.

†Calculated by dividing incidence rate ratio for age 70-75 by incidence rate ratio for age 76-80

In women aged 76-80, the incidence of early stage breast cancer slightly decreased (253.9 cases per 100 000 women before 1998 to 212.4 cases per 100 000 women after 2003, incidence rate ratio 0.84, 0.79 to 0.88, P<0.001). In contrast, the incidence rate of advanced stage breast cancer did not significantly change in the evaluated time frame (66.0 cases per 100 000 women before 1998 to 67.2 cases per 100 000 women after 2003, incidence rate ratio 1.02, 0.92 to 1.13, P=0.74). Consequently, the relative ratios of the incidence rate ratios in both age groups were almost similar to those in women aged 70-75 years (table 2).

Ratio between early stage and advanced stage tumours

We calculated the ratio between early stage and advanced stage tumours. The incidence rate of early stage tumours increased by 114.2 cases per 100 000 women (362.9 to 248.7), whereas the incidence rate of advanced stage tumours decreased by 6.8 cases per 100 000 women (58.6 to 51.8). Hence, the ratio of advanced and early stage tumours was 114.2/6.8=19.7 cases per 100 000 women per year. This means that for every advanced stage tumour that was prevented by screening, 19.7 “extra” early stage tumours were diagnosed.

Sensitivity analyses

Supplementary table 1 presents additional sensitivity analyses. The results were not altered by changing the length of the screening uptake period. However, the exclusion of patients with stage II disease resulted in a stronger increase of early stage breast cancer in women aged 70-75 years (see supplementary table 1, incidence rate ratio 2.39, 95% confidence interval 2.25 to 2.54, P<0.001 during active screening compared with the prescreening period). Finally, by analysing the year of diagnosis as a continuous variable, starting from 1998, we observed no change in incidence rates over time (1.00, 1.00 to 1.00, P<0.88 per year for early stage tumours, and 1.00, 1.00 to 1.01, P=0.37 per year for advanced stage tumours).

Discussion

The extension of the upper age limit for the mass breast cancer screening programme in the Netherlands to 75 years has not resulted in a strong decrease in incidence of advanced breast cancer, whereas the incidence of early stage breast cancer strongly increased in patients aged 70 to 75 years.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The main strength of this study is the well registered and detailed information from a national cancer registry of a large number of unselected older women with breast cancer over a long period. This made it possible to evaluate time trends of incidence rates of tumour stages after extension of the age limit for the screening programme to 75 years in 1998. Using this methodology, we were able to assess the benefits of screening older women without inducing several forms of bias. Furthermore, we were able to adjust the observed changes in incidence rates for changes in incidence rates in the general population using a cohort of women aged 76-80 years during the same period. Also, the breast cancer screening programme in the Netherlands is accessible for all citizens and the attendance rate was as high as 73% in women aged 70-75 years between 1998 and 2007.19

This study also has its limitations. The length of follow-up after implementation of the screening programme was possibly not long enough to result in a decrease in incidence of advanced tumours. However, a previous study assessed the incidence rates of localised, regional and metastatic breast cancer after implementation of screening in the United States. A (small) decline in metastatic breast cancer occurred around three years after implementation of screening.17 Hence it is likely that any decline in diagnosis of advanced stage tumours would have occurred after three years, and we extended this so called screening uptake period to five years to ensure that we did not miss a reduction as a result of the definition of our screening uptake period. In addition, we lengthened the period to six years in our sensitivity analyses, which did not alter the results. Furthermore, the incidence rate of early stage breast cancer in the age group 76-80 years was likely to be influenced by breast cancer screening as well, as early stage tumours in patients aged 75 years were not diagnosed the year these patients turned 76 years. Finally, it may seem strange that the incidence rates of both early and advanced stage tumours did not significantly change over time when the year of diagnosis was handled as a continuous variable. This is most likely explained by the observed changes in incidence rates not being linear (figure).

Comparison with other studies

Current guidelines on breast cancer screening are mostly based on randomised clinical trials that were performed in the 1970s and 80s.9 However, these trials rarely included patients aged more than 70 years, and no patients over the age of 74 years were included.9 Therefore we can only compare our findings with those of previous observational studies. Although some previous observational studies investigated the incidence of advanced stage cancer after implementation of a breast cancer screening programme,20 21 they did not report specific incidence rates in older women. For example, a recent study evaluated three decades of screening mammography in women aged 40 years and older in the United States, and concluded that screening has only marginally reduced the rate at which women present with advanced cancer.20 In contrast, a recent study assessed the incidence of advanced breast cancer after implementation of mammography screening in the United States using the same data, but with adjustments for prescreening incidence trends.22 This study did find a decline in the incidence of advanced breast cancer. However, it is difficult to adjust for changes in breast cancer incidence using data from another time frame, as many other circumstances may have changed since that period and it is therefore unclear if this is a reliable method. Therefore, in the current study we chose to use a control group that did not have access to mammography screening in the same time frame.

Another study that investigated the incidence of advanced stage tumours in the south eastern part of the Netherlands in women aged 40-75 years from 1980 to 2009 found no decrease in advanced stage tumours in women aged 50-75 years.21 In addition, a systematic review from 2011 evaluated the incidence rates of advanced breast cancer after implementation of mass screening in several European countries. Again, this study concluded that, in general, incidence rates of advanced breast cancer did not change much despite good participation (7-15 years) in mammographic screening.23 Finally, a recent Norwegian study showed that the incidence of advanced stage breast cancer in women aged 50-69 years did not increase after implementation of mass screening.24 Hence our findings are mostly in line with these studies that included younger women and may suggest that the capacity for screening to impact the incidence of advanced breast cancer may be limited.

In contrast, several studies that investigated the effects of the breast cancer screening programme on survival, concluded that the screening programme contributed to an increase in breast cancer survival rates in the Netherlands.25 26 27 These contradictory results can be explained by the fact that studying survival rates as an indicator for the effect of screening programmes is notoriously difficult because of the several forms of bias present in such studies.16 Firstly, as a result of increased detection of early stage tumours, possible favourable effects of screening on survival are generally overestimated since a large percentage of early stage screen detected tumours are indolent and have an excellent prognosis.17 Consequently, interval detected tumours are generally more aggressive.15 By comparing screen detected tumours with interval detected tumours, observed survival differences are often attributed to favourable effects of breast cancer screening, whereas the observed survival difference can be (partly) explained by differences in tumour biology. This phenomenon is called length-time bias.28 Secondly, lead-time bias is usually present: breast cancer diagnosis is confirmed at an earlier stage, which means that patients live longer knowing that they have breast cancer while the actual cancer survival is not higher.28 Thirdly, women who attend a screening programme are generally healthier than those who do not,29 30 31 which leads to a self selection bias. This was shown in a recent study, which concluded that patients aged 80 years and older with a screen detected breast cancer had a lower a risk of breast cancer mortality than non-screen detected patients of similar age, but also had a lower risk of mortality from other causes than breast cancer. This suggests that the results were strongly biased by the fact that healthier women more often attend the mass screening programme.29

As a result of these types of bias, several studies state that the most appropriate way to study the benefits of a screening programme on incidence rates of advanced tumours in population based studies is to investigate the effects of the screening programme.17 20 32 Esserman et al proposed three hypothetical scenarios after implementation of a breast cancer screening programme in the overall population, independent of age.17 In the most ideal scenario, the incidence of early stage tumours increases while the incidence of advanced stage tumours decreases and the total number of cases remains equal. In the worst case scenario, the incidence of early stage tumours increases without a decrease in incidence of advanced stage tumours. The third, intermediate case scenario is between these two scenarios. The results of our study mostly resemble either the intermediate case scenario or even the worst case scenario according to Esserman et al, as the strong decrease in advanced stage breast cancer that should be observed in a successful screening programme remained absent in our data. Since we have shown that each “prevented” advanced stage tumour resulted in 19.7 “extra” and therefore overdiagnosed early stage tumours, this implies that mass screening in women aged 70-75 years leads to a considerable proportion of tumours that are overdiagnosed.

Conclusions and policy implications

Overdiagnosis and overtreatment could have a great impact on quality of life and physical function of older women with breast cancer, as they are at increased risk of adverse outcomes of breast cancer treatment.5 6 7 Consequently, from a certain age the unfavourable effects of screening may outweigh the benefits.12 Moreover, the additional costs of treating overdiagnosed tumours could result in a tremendous increase in health expenditure as a result of the screening programme, with no actual health benefits. Interestingly, Cancer Research UK is currently undertaking a large randomised controlled trial (clinical trials register NCT01081288) within the UK National Health Service breast cancer screening programme in women aged 71-73 years in which an age extension from 70 to 73 years is randomly phased in, allowing the investigators to evaluate the effects of screening on breast cancer incidence and mortality.33 Until the results of this trial become available, we propose that routine breast cancer screening in women aged more than 70 years should not be performed on a large scale. Instead, the harms and benefits of screening should be weighed on a personalised basis, taking remaining life expectancy, breast cancer risk, functional status, and patients’ preferences into account.34 35

In conclusion, the extension of the upper age limit for breast cancer screening to 75 years has not led to a strong decrease in incidence of advanced stage breast cancer, whereas the incidence of early stage tumours has strongly increased. This implies that the effect of the screening programme in older women is limited and may lead to overdiagnosis.

What is already known on this topic

The benefit of breast cancer screening in older women has not been proved, as randomised trials have rarely included women aged more than 60

Some observational studies have hinted at a beneficial effect of screening in older women, but these generally contained several forms of bias

The risk of adverse events of breast cancer treatment strongly increases with age and comorbidity status, which puts older patients at risk for negative effects of overtreatment

What this study adds

The implementation of mass breast screening in women aged 69-75 years in the Netherlands has not led to a strong decrease in incidence of advanced stage breast cancer

The incidence of early stage tumours, however, has strongly increased

The effect of the screening programme in older women is limited and may lead to overdiagnosis

We thank the registration teams of the comprehensive cancer centres for the collection of data for the Netherlands cancer registry and the scientific staff of the Netherlands cancer registry. This paper was orally presented at the European Breast Cancer Conference, Glasgow, 21 March 2014.

Contributors: NdG and AdC performed all data analyses. NdG provided the figures. NdG, EB, AdC, and GL contributed to the study design. All authors were responsible for interpretation of the data and writing and editing the manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. NdG is guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by the Alpe d’Huzes Foundation (UL-2011-5263). The funding source was not involved in any part of the study design, data collection, analyses or drafting of the manuscript.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Netherlands cancer registry. Patient consent was not obtained but the presented data are anonymised and risk of identification is low.

Data sharing: Patient level data are available from the corresponding author at G.J.Liefers@lumc.nl.

Transparency: The lead author (NdG) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;349:g5410

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Results of sensitivity analyses

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeSantis C, Siegel R, Bandi P, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2011. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:409-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braithwaite D, Satariano WA, Sternfeld B, Hiatt RA, Ganz PA, Kerlikowske K, et al. Long-term prognostic role of functional limitations among women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1468-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patnaik JL, Byers T, Diguiseppi C, Denberg TD, Dabelea D. The influence of comorbidities on overall survival among older women diagnosed with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:1101-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Glas NA, Kiderlen M, Bastiaannet E, de Craen AJ, van de Water W, van de Velde CJ, et al. Postoperative complications and survival of elderly breast cancer patients: a FOCUS study analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013;138:561-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van de Water W, Bastiaannet E, Hille ET, Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg EM, Putter H, Seynaeve CM, et al. Age-specific nonpersistence of endocrine therapy in postmenopausal patients diagnosed with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: a TEAM study analysis. Oncologist 2012;17:55-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurria A, Brogan K, Panageas KS, Pearce C, Norton L, Jakubowski A, et al. Patterns of toxicity in older patients with breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2005;92:151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van de Water W, Markopoulos C, van de Velde CJ, Seynaeve C, Hasenburg A, Rea D, et al. Association between age at diagnosis and disease-specific mortality among postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. JAMA 2012;307:590-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paesmans M, Ameye L, Moreau M, Rozenberg S. Breast cancer screening in the older woman: an effective way to reduce mortality? Maturitas 2010;66:263-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:716-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NABON. Richtlijn Mammacarcinoom versie 2.0. 2012. www.oncoline.nl/mammacarcinoom.

- 12.Fracheboud J, Groenewoud JH, Boer R, Draisma G, de Bruijn AE, Verbeek AL, et al. Seventy-five years is an appropriate upper age limit for population-based mammography screening. Int J Cancer 2006;118:2020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badgwell BD, Giordano SH, Duan ZZ, Fang S, Bedrosian I, Kuerer HM, et al. Mammography before diagnosis among women age 80 years and older with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galit W, Green MS, Lital KB. Routine screening mammography in women older than 74 years: a review of the available data. Maturitas 2007;57:109-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esserman LJ, Shieh Y, Rutgers EJ, Knauer M, Retel VP, Mook S, et al. Impact of mammographic screening on the detection of good and poor prognosis breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;130:725-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox B, Sneyd MJ. Bias in breast cancer research in the screening era. Breast 2013;22:1041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esserman L, Shieh Y, Thompson I. Rethinking screening for breast cancer and prostate cancer. JAMA 2009;302:1685-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Statistics Netherlands. 2013. www.statline.nl.

- 19.Fracheboud J, Ineveld D, Bruijn M. National evaluation of breast cancer screening in the Netherlands. 1990-2007 (XII), 12th evaluation report. 2009, 1-106.

- 20.Bleyer A, Welch HG. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1998-2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nederend J, Duijm LE, Voogd AC, Groenewoud JH, Jansen FH, Louwman MW. Trends in incidence and detection of advanced breast cancer at biennial screening mammography in The Netherlands: a population based study. Breast Cancer Res 2012;14:R10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helvie MA, Chang JT, Hendrick RE, Banerjee M. Reduction in late-stage breast cancer incidence in the mammography era: implications for overdiagnosis of invasive cancer. Cancer 2014;120:2649-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Autier P, Boniol M, Middleton R, Dore JF, Hery C, Zheng T, et al. Advanced breast cancer incidence following population-based mammographic screening. Ann Oncol 2011;22:1726-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lousdal ML, Kristiansen IS, Moller B, Stovring H. Trends in breast cancer stage distribution before, during and after introduction of a screening programme in Norway. Eur J Public Health 2014; published online 4 Mar. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Otto SJ, Fracheboud J, Looman CW, Broeders MJ, Boer R, Hendriks JH, et al. Initiation of population-based mammography screening in Dutch municipalities and effect on breast-cancer mortality: a systematic review. Lancet 2003;361:1411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otto SJ, Fracheboud J, Verbeek AL, Boer R, Reijerink-Verheij JC, Otten JD, et al. Mammography screening and risk of breast cancer death: a population-based case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012;21:66-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Broeders MJ, Verbeek AL, Straatman H, Peer PG, Jong PC, Beex LV, et al. Repeated mammographic screening reduces breast cancer mortality along the continuum of age. J Med Screen 2002;9:163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pelikan S, Moskowitz M. Effects of lead time, length bias, and false-negative assurance on screening for breast cancer. Cancer 1993;71:1998-2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Badgwell BD, Giordano SH, Duan ZZ, Fang S, Bedrosian I, Kuerer HM, et al. Mammography before diagnosis among women age 80 years and older with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aarts MJ, Voogd AC, Duijm LE, Coebergh JW, Louwman WJ. Socioeconomic inequalities in attending the mass screening for breast cancer in the south of the Netherlands—associations with stage at diagnosis and survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;128:517-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zackrisson S, Lindstrom M, Moghaddassi M, Andersson I, Janzon L. Social predictors of non-attendance in an urban mammographic screening programme: a multilevel analysis. Scand J Public Health 2007;35:548-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Autier P, Boniol M. Breast cancer screening: evidence of benefit depends on the method used. BMC Med 2012;10:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.NHS Breast Screening Programme. Evaluating the age extension of the NHS Breast Screening Programme. 2012. www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-help/trials/a-study-to-evaluate-an-age-extension-of-the-nhs-breast-screening-programme.

- 34.Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: a framework for individualized decision making. JAMA 2001;285:2750-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walter LC, Schonberg MA. Screening mammography in older women: a review. JAMA 2014;311:1336-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Results of sensitivity analyses