Abstract

Purpose

To compare the risks of re-admission, reoperation, and mortality within 90 days of surgery in orthopedic departments with well-documented fast-track arthroplasty programs with those in all other orthopedic departments in Denmark from 2005 to 2011.

Methods

We used the Danish hip and knee arthroplasty registers to identify patients with primary total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty. Information about re-admission, reoperation, and mortality within 90 days of surgery was obtained from administrative databases. The fast-track cohort consisted of 6 departments. The national comparison cohort consisted of all other orthopedic departments. Regression methods were used to calculate relative risk (RR) of adverse events, adjusting for age, sex, type of fixation, and comorbidity. Cohorts were divided into 3 time periods: 2005–2007, 2008–2009, and 2010–2011.

Results

79,098 arthroplasties were included: 17,284 in the fast-track cohort and 61,814 in the national cohort. Median length of stay (LOS) was less for the fast-track cohort in all 3 time periods (4, 3, and 3 days as opposed to 6, 4, and 3 days). RR of re-admission due to infection was higher in the fast-track cohort in 2005–2007 (1.3, 95% CI: 1.1–1.6) than in the national cohort in the same time period. This was mainly due to urinary tract infections. RR of re-admission due to a thromboembolic event was lower in the fast-track cohort in 2010–2011 (0.7, CI: 0.6–0.9) than in the national cohort in the same time period. No differences were seen in the risk of reoperation and mortality between the 2 cohorts during any time period.

Interpretation

The general reduction in LOS indicates that fast-track arthroplasty programs have been widely implemented in Denmark. At the same time, it appears that dedicated fast-track departments have been able to optimize the fast-track program further without any rise in re-admission, reoperation, and mortality rates.

Even though the main principles of total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) have been unchanged for years, the clinical pathways for patients have been changed in many respects during the past decade, to enhance recovery, reduce morbidity, increase patient satisfaction, and reduce length of stay (LOS). These principles—often known as fast-track surgical programs, enhanced recovery programs, or rapid recovery protocols (they are known by many names)—have been widely adopted today for THA and TKA in Denmark (Kehlet 2013).

Clinical studies have shown that the risks of thromboembolic complications (Husted et al. 2010a) and mortality (Malviya et al. 2011) have become reduced in THA and TKA when comparing the same department before and after implementation of fast-track programs. Also, patient-related outcomes such as pain, quality of life (Larsen et al. 2008, Raphael et al. 2011, den Hertog et al. 2012), and patient satisfaction are positively associated with fast-track surgery (Larsen et al. 2008, Machin et al. 2013). Thus, the implementation of fast-track programs reduces LOS in patients who have undergone THA and TKA (Husted and Holm 2006, Larsen et al. 2008, Malviya et al. 2011, Raphael et al. 2011, den Hertog et al. 2012, Hartog et al. 2013). In Denmark, LOS for both THA and TKA was reduced from 10–11 days in 2000 to 4 days in 2009 (Husted et al. 2012), indicating a general trend towards use of fast-track surgery in most or all of the orthopedic departments in Denmark.

Today, 10 Danish orthopedic departments, supported by the Lundbeck Foundation Center for Fast-track Hip and Knee Replacement, have described their fast-track programs and results in detail (www.fthk.dk, Kehlet and Søballe 2010, Husted et al. 2010b). A common denominator for these departments is their compliance to well-documented interdisciplinary logistic and clinical instructions— all of which are known to be significant factors for improved and accelerated recovery (Barberi et al. 2009, Bozic et al. 2010). We hypothesized that results regarding morbidity and mortality from the fast-track departments would be comparable to or even better than results from other departments that use standard, less systematically described treatment regimes after THA and TKA.

We therefore investigated whether orthopedic departments with well-documented fast-track THA and TKA programs had lower short-term risk of re-admission, reoperation, and mortality than all other orthopedic departments in Denmark during different stages of implementation of the fast-track programs in the period 2005–2011.

Patients and methods

Setting

All citizens in Denmark have access to a tax-supported healthcare system, which allows free access to public hospitals and general practitioners, as well as private hospitals. At birth, citizens are assigned a unique 10-digit personal identification number (CPR) encoding their date of birth and sex. This allows unambiguous linkage between all the Danish medical databases and the administrative registers, which individuals in the Danish healthcare system must be part of (Frank 2000).

We used the Danish Hip Arthroplasty Register (DHR) and the Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register (DKR) to identify all the primary THA and TKA procedures performed at public and private hospitals in Denmark. The primary procedures were then linked to the Danish Civil Registration System (CRS) which contains all CPR numbers. The CRS has records on vital statistics for all Danish citizens (from April 1968 to the present), and is updated on a daily basis. The primary procedures have also been linked to the Danish National Patient Register (NPR), which has held data on all inpatient admissions to Danish hospitals since 1977 and outpatient visits since 1995. Each record in the NRP contains the patient’s CPR number and information on treatment procedures, surgical procedures, primary discharge diagnosis, and up to 20 secondary discharge diagnoses. Diagnoses have been coded according to ICD-8 from 1977 to 1994, and ICD-10 thereafter.

Fast-track cohort

The fast-track cohort consisted of all patients who had undergone THA or TKA for osteoarthritis and who had been treated in the original 6 orthopedic departments participating in the Lundbeck Foundation Center for Fast-track Hip and Knee Replacement collaboration (www.fthk.dk) and registered in the DHR and DKR from January 2005 to September 2011 (Figure 1). The fast-track cohort was divided into 3 time periods: an early period from January 1, 2005 to December 31, 2007, when the fast-track program (or part of it) was launched but still in its infancy; an intermediate period from January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2009, when the 6 departments had implemented a full-scale fast-track program; and a recent period from January 1, 2010 to September 30, 2011, when the 6 departments improved the fast-track program by optimizing the different parts of it. Patients with no primary diagnosis and patients who had emigrated during the follow-up period were excluded (455 in total).

Figure 1.

The 6 orthopedic departments supported by the Lundbeck Foundation Center for Fast-track Hip and Knee Replacement that formed the fast-track cohort.

Fast-track program

All 6 departments developed a fast-track program for THA and TKA and implemented it for all patients (Husted et al. 2010b, Kehlet and Søballe 2010). The program consisted of (1) logistic elements, such as preoperative information including information on intended LOS and admission on the day of surgery; (2) perioperative elements: spinal anesthesia, local infiltration analgesia, plans for fluid therapy, small standard incisions, blood-sparing strategies, no drains, compression bandages, and cooling; and (3) postoperative elements, consisting of deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis starting 6–8 h postoperatively and continuing until discharge, multimodal opioid-sparing analgesia, mobilization 2-4 h postoperatively, and discharge when functional criteria were met. In addition, during their ongoing research, the departments strive for continued optimization of different aspects of the fast-track total hip and knee arthroplasty program.

National comparison cohort

The fast-track cohort was compared with a national comparison cohort consisting of patients who had been treated at any other orthopedic department in Denmark during the same period, and registered in the DHR and DKR. The inclusion and exclusion criteria in the national comparison cohort were identical to those in the fast-track cohort. The national comparison cohort consisted of patients treated at public or private hospitals.

The orthopedic departments in the national comparison cohort had undoubtedly implemented fast-track treatment to some extent during the period of interest, but not in the same systematic and consistent way as the departments in the fast-track cohort. There was no systematic information on which fast-track components had been implemented and when.

Outcome

The outcome of interest was re-admission due to infection, re-admission due to thromboembolic event, reoperation, and death—all within 90 days of the primary procedure. Information about death was collected from the CRS. Information regarding the remaining outcomes was collected using the NRP. Re-admissions due to infection involved infections related to surgery (DT845 in relation to surgery), urinary tract infection (DN30.0, DN30.8, and DN30.9), and pneumonia (DJ12–DJ18). Re-admissions due to a thromboembolic event involved stroke (DI60–DI64), myocardial infarction (DI21, DI24), deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (DI801, DI802, DI803, DI808, DI809, DI822, DI823, DI828, and DI829), and pulmonary embolism (DI26). Reoperation was defined as any new hip- or knee-related surgical procedure (DT845 in relation to surgery). For codes in relation to surgery, see Supplementary data, Appendix 1.

Statistics

The descriptive statistics included mean age at primary procedure, sex, median LOS, type of fixation, and comorbidity. Differences in descriptive parameters were tested with Student’s t-test, Wilcoxon signed rank test, and chi-square test; results are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values. A LOS of more than 30 days (421 cases in total, 0.5%) was mainly considered to be registration error and was recoded as 31-day LOS. Differences in the absolute risk of re-admission, reoperation, and mortality between the fast-track cohort and the national comparison cohort were tested with chi-square test. All risk estimates are presented with CI and p-values.

We used logistic regression to access the odds ratio (OR) as a measure of RR when comparing risk of re-admission and reoperation between the fast-track cohort and the national comparison cohort. Difference in mortality risk between the fast-track cohort and the national comparison cohort was examined using Cox regression in order to calculate hazard ratios as a measure of RR. The proportionality was validated with log-log plots. Both regression models were presented with 95% CI and p-values relative to the national comparison cohort.

The following variables were considered as confounders: age at primary procedure (in categories 10–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and 80+), sex, type of fixation (in the categories cemented, uncemented, or hybrid) and comorbidity measured with the Charlson comorbidity index. All diagnoses and procedures from 1977 to primary procedure registered in the NRP formed the basis of the calculation of Charlson comorbidity index. Comorbidity was divided into 3 categorical groups: weighted index of comorbidity = 0, weighted index of comorbidity = 1–2, and weighted index of comorbidity ≥ 3.

All analyses were done on THAs, TKAs, and both combined. Only the combined results are described in this article. Separate results for THA and TKA on specific causes are shown in Supplementary data, Appendix 2, and are reported in the text where appropriate. If more than one re-admission or reoperation occurred, only the first contributed to the analysis. The analysis was done using Stata 12 software.

Ethics

Permission was obtained from the Danish Data Protection Agency (reference number: 2012-41-0636). No permission was needed from the Danish Ethics Committee.

Results

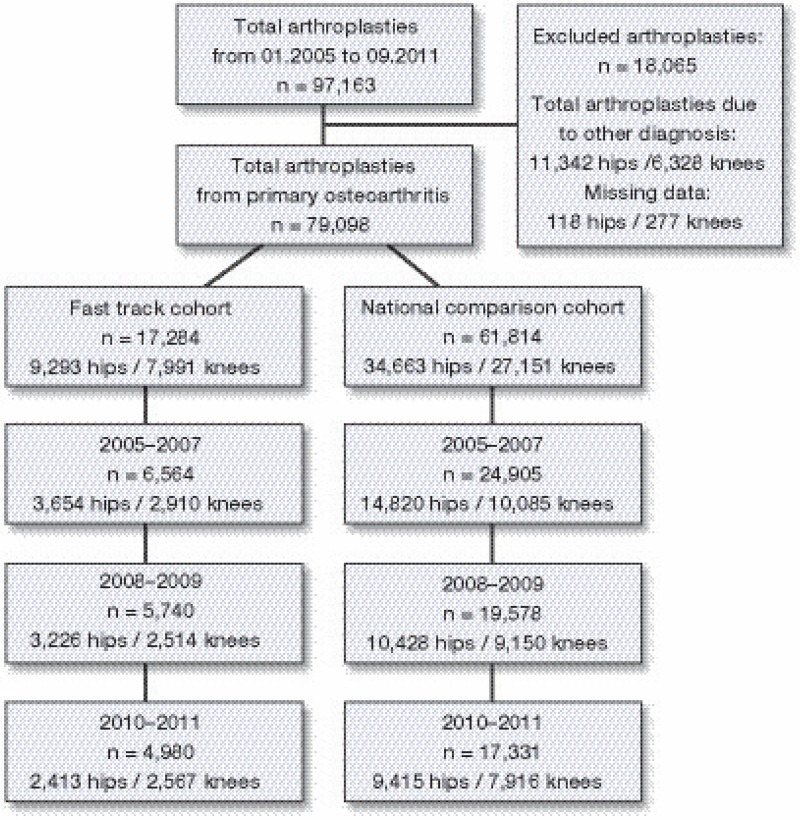

79,098 joint arthroplasties in 66,733 patients were included in the study (Figure 2). THA accounted for 43,956 procedures in 37,716 patients. TKA accounted for 35,142 procedures in 29,017 patients. Of the total cohort, 54,866 patients underwent 1 procedure, 11,421 had 2 procedures, 394 had 3 procedures, and 52 had 4 procedures. The fast-track cohort involved 17,284 procedures whereas the national comparison cohort involved 61,814 procedures.

Figure 2.

79,098 total hip and knee arthroplasties were included in the study. The fast-track cohort consisted of 17,284 arthroplasties. The national comparison cohort consisted of 61,814 arthroplasties.

Patients included in the early and intermediate fast-track cohort were slightly younger than the patients in the national cohort, whereas no significant difference in age was observed between the 2 cohorts in the recent period (Table 1a). The fast-track cohort included a higher proportion of men in both the early period and the recent period. LOS was shorter for the fast-track cohort in all 3 periods. In the fast-track cohort, median LOS was reduced from 4 days to 3 days. In the national cohort, the median LOS was reduced from 6 days to 3 days. There were no significant differences in the distribution of comorbidity index groups between the fast-track cohort and the national cohort (Table 1b).

Table 1a.

Patient characteristics according to cohort and time period

| Age |

Sex |

LOS |

Type of fixation a

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | p-value | Female % | p-value | Median (10–90%) | p-value | THA % | p-value | TKA % | p-value | |

| 2005–2007 | ||||||||||

| Fast-track | 69 (10) | < 0.001 | 58 | 0.02 | 4 (2–8) | < 0.001 | 19/59/22 | < 0.001 | 91/0/9 | < 0.001 |

| National | 69 (10) | 60 | 6 (3–10) | 32/47/22 | 76/10/14 | |||||

| 2008–2009 | ||||||||||

| Fast-track | 68 (10) | < 0.001 | 58 | 0.1 | 3 (2–9) | < 0.001 | 10/65/25 | < 0.001 | 89/3/8 | < 0.001 |

| National | 69 (10) | 59 | 4 (2–7) | 19/66/15 | 81/6/13 | |||||

| 2010–Sept. 2011 | ||||||||||

| Fast-track | 69 (10) | 0.1 | 57 | 0.01 | 3 (2–5) | < 0.001 | 5/66/29 | < 0.001 | 91/5/4 | < 0.001 |

| National | 69 (9) | 59 | 3 (2–7) | 18/71/11 | 77/4/19 | |||||

cemented/uncemented/hybrid

Table 1b.

Charlson comorbidity index distribution (percent) in fast-track and national comparison cohorts according to time period

| Comorbidity index |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1–2 | ≥ 3 | p-value | |

| 2005–2007 | ||||

| Fast-track | 61 | 31 | 8 | 0.1 |

| National | 62 | 30 | 8 | |

| 2008–2009 | ||||

| Fast-track | 59 | 31 | 10 | 0.2 |

| National | 60 | 31 | 9 | |

| 2010–Sept. 2011 | ||||

| Fast-track | 57 | 33 | 10 | 0.2 |

| National | 57 | 33 | 10 | |

The fast-track cohort showed a different pattern of type of fixation than the national cohort, especially regarding THA (Table 1a). In general, the use of cemented hip implants was reduced in favor of uncemented or hybrid implants, but the distribution of fixation types was very diverse between the cohorts. The fast-track cohort and the national cohort had reduced use of cemented hip implants over the 3 periods—from 19% to 5% and from 32% to 18%, respectively. The use of uncemented hip implants increased in both cohorts during all 3 periods, but was more pronounced in the national cohort. The use of hybrid implants increased in the fast-track cohort and decreased in the national cohort through the intermediate and recent time periods. For TKA, the main fixation type in all 3 periods was cemented (approximately 90% in the fast-track cohort and 80% in the national cohort), followed by hybrid fixation.

Risk of re-admission due to infection

The risk of re-admission due to infection was higher in the fast-track cohort than in the national comparison cohort during all 3 periods, but particularly in the early period (Table 2). The fast-track cohort had a 32% (CI: 1.1–1.6) higher adjusted RR of re-admission due to infection compared to the national cohort in the early period (Table 3). The most crucial contributory factor to the increased risk of re-admission due to infection in the early period was an increased risk of urinary tract infection (UTI), especially in TKA patients (Supplementary data, Appendix 2). For both THA and TKA, the risk in the fast-track cohort in the early period was approximately twice that in the national cohort: for hips, 1.4% (CI: 1.1–1.9) vs. 0.7% (CI: 0.6–0.8) (p < 0.001) and for knees, 1.0% (CI: 0.7–1.5) vs. 0.7% (CI: 0.5–0.9) (p = 0.07). This increased risk of urinary tract infections in THA in the fast-track cohort was again apparent in the most recent period, even though it was reduced in size (0.9% (CI: 0.6–1.4) vs. 0.4% (CI: 0.3–0.6) (p < 0.001). The risk of re-admission due to infection for specific causes is given in Supplementary data, Appendix 2.

Table 2.

Absolute risk of mortality, reoperation, and re-admission due to infection or thromboembolic event according to cohort and time period. All 90 days postoperatively

| n | Risk % (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Re-admission due to infection | |||

| 2005–2007 | |||

| Fast-track | 168 | 2.6 (2.2–3.0) | 0.01 |

| National | 500 | 2.0 (1.8–2.2) | |

| 2008–2009 | |||

| Fast-track | 119 | 2.1 (1.7–2.5) | 0.4 |

| National | 368 | 1.9 (1.7–2.1) | |

| 2010–Sept. 2011 | |||

| Fast-track | 102 | 2.0 (1.7–2.5) | 0.6 |

| National | 336 | 1.9 (1.7–2.2) | |

| Re-admission due to thromboembolic event | |||

| 2005–2007 | |||

| Fast-track | 131 | 2.0 (1.7–2.4) | 0.2 |

| National | 557 | 2.2 (2.1–2.4) | |

| 2008–2009 | |||

| Fast-track | 120 | 2.1 (1.7–2.5) | 0.8 |

| National | 397 | 2.0 (1.8–2.2) | |

| 2010–Sept. 2011 | |||

| Fast-track | 82 | 1.7 (1.3–2.0) | 0.01 |

| National | 385 | 2.2 (2.0–2.5) | |

| Reoperation | |||

| 2005–2007 | |||

| Fast-track | 111 | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | 0.8 |

| National | 407 | 1.6 (1.5–1.8) | |

| 2008–2009 | |||

| Fast-track | 117 | 2.0 (1.7–2.4) | 0.3 |

| National | 354 | 1.8 (1.6–2.0) | |

| 2010–Sept. 2011 | |||

| Fast-track | 69 | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.5 |

| National | 261 | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | |

| Mortality | |||

| 2005–2007 | |||

| Fast-track | 33 | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 0.6 |

| National | 114 | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | |

| 2008–2009 | |||

| Fast-track | 31 | 0.5 (0.4–0.8) | 0.2 |

| National | 79 | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | |

| 2010–Sept. 2011 | |||

| Fast-track | 19 | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | 0.4 |

| National | 81 | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) |

Table 3.

Relative risk of mortality, reoperation, and re-admission due to infection or thromboembolic event in the fast-track cohort according to time period. All 90 days postoperatively

| Adjusted RR a | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Re-admission due to infection | ||

| 2005–2007 | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | < 0.01 |

| 2008–2009 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.3 |

| 2010–Sept. 2011 | 1.1 (0.8–1.3) | 0.7 |

| Re-admission due to thromboembolic event | ||

| 2005–2007 | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.3 |

| 2008–2009 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.7 |

| 2010–Sept. 2011 | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) | 0.01 |

| Reoperation | ||

| 2005–2007 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.7 |

| 2008–2009 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.3 |

| 2010–Sept. 2011 | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.5 |

| Mortality | ||

| 2005–2007 | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 0.5 |

| 2008–2009 | 1.3 (0.8–2.0) | 0.3 |

| 2010–Sept. 2011 | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 0.4 |

OR for re-admission and reoperation, HR for mortality.

Risk of re-admission due to a thromboembolic event

While there were no differences in the risk of re-admission due to a thromboembolic event between the fast-track cohort and the national cohort in the early and intermediate periods, there was a reduced risk for the fast-track cohort in the most recent period (Table 2). Patients included in the fast-track cohort in the recent period had a 27% (CI: 0.6–0.9) lower adjusted RR of sustaining a thromboembolic event within 90 days of surgery than patients included in the national comparison cohort (Table 3). The main contributor to the significant difference in thromboembolic events in the recent period was reduced risk of DVT (Supplementary data, Appendix 2). For THA, the risk was 0.5% (CI: 0.3–0.9) in the fast-track cohort and it was 1.1% (CI: 0.9–1.3) in the national cohort (p = 0.02). For TKA, the risk was also reduced—although not significantly (1.1%, CI: 0.7–1.6 vs. 1.5%, CI: 1.3–1.8; p = 0.1). The risk of re-admission for specific causes of thromboembolic events is given in Supplementary data, Appendix 2.

Risk of reoperation

There were no significant differences between the fast-track cohort and the national cohort regarding reoperation in either the early, the intermediate, or the recent time period (Tables 2 and 3).

Mortality risk

No significant differences were seen in 90-day mortality risk between the fast-track cohort and the national cohort during the 3 different periods of the study. The absolute 90-day mortality risks were almost identical (from 0.4 to 0.5) for both cohorts during all 3 periods (Table 2) and the adjusted RR did not differ from 1 in any of the 3 periods (Table 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate implementation of fast-track programs in THA and TKA in a population-based cohort. For our fast-track cohort, we found an increased risk of re-admission due to infection while the fast-track programs were being launched and a reduced risk of re-admission due to a thromboembolic event after the fast-track programs were fully implemented, compared to a national cohort.

A major limitation in this study was the extent to which fast-track programs had been implemented in departments corresponding to the national comparison cohort. The reduction in median LOS from 6 days to 3 days in the national cohort indicates that fast-track programs had been gradually implemented during the entire study period, but we have no information about which fast-track components were involved and when. Furthermore, we do not know whether fast-track programs had been introduced to all patients or to selected patients only. This weakness was especially evident in the most recent time period, from 2010 to 2011. It complicated the comparison of cohorts and because of this, impeded the attribution of findings from this time period to use of the fast-track program.

Re-admission due to infection was more common in the fast-track cohort in the early period. The increase was mainly caused by an increased risk of UTI. An equivalent finding regarding UTI in THA in the recent period suggests that increased risk of re-admission due to UTI may be linked to the fast-track program. In the early time period, this link can be explained. The shift from general anesthesia to regional analgesia in the fast-track cohort in the early time period may have driven the fast-track departments to routine use of indwelling urinary catheter because of fear of urinary retention. A fear that is unfounded (Balderi and Carli 2010). The difference in LOS could also explain the difference in RR of re-admission due to infection in the early period. Severe infections—including urinary tract infections—that call for re-admission would be recorded in the fast-track cohort, while an analogous infection in the national comparison cohort while the patient was still in hospital might not be. These explanations may hold for the early time period, but they would be inconclusive for THA in the most recent time period. Here, explanations such as differences in prophylactic antibiotics or differences in blood transfusion strategies might be valid, but they still need to be investigated further. We know from a study by Jans et al. (2011) that the transfusion rates in orthopedic departments in Denmark varied from 7% to 71% in 2008. If the fast-track departments had less restrictive use of blood transfusions—using more blood transfusions in order to mobilize patients early—an increased risk of UTI may have been a consequence. On the other hand, we have no reason to believe that there was a difference in blood transfusion strategies. The annual reports of the DHR have quoted hospital transfusion rates since 2006. The reports show an overall reduction in blood transfusions (from 21% in 2006 to 13% in 2011), and that the variation in fast-track departments was no more pronounced than the variation in departments corresponding to the national cohort (www.dhr.dk).

A large contributor to a reduced risk of re-admission due to a thromboembolic event in the fast-track cohort in the most recent period was a reduction in DVT. The risk of re-admission due to DVT in the fast-track cohort was less than the risk in the national comparison cohort and less than that found in 2 earlier Danish studies from 1995–2007, where the incidence of DVT leading to re-admission after total hip and knee replacement was 1.1% (Pedersen et al. 2010, 2011). In a clinical trial by Malviya et al. (2011), these workers found a comparable risk of re-admission due to DVT of 0.6% in an enhanced recovery program group 60 days postoperatively. The shorter follow-up time in the British study might lead to slightly higher incidence of DVT at 90 days, and by that give preference to our finding. The reduced risk of DVT in the most recent period indicates that the fast-track departments were able to optimize the fast-track program even more relative to other departments in Denmark. Although the departments in the national cohort have implemented fast-track programs and reaped the benefits in terms of reduced LOS, the original fast-track departments still contribute to the development of fast-track programs.

Use of pharmacological DVT prophylaxis is routine in THA and TKA in Denmark (Pedersen et al. 2010, 2011). Pharmacological prophylaxis was prescribed in 99% of the procedures in both cohorts. The Danish guidelines for THA and TKA recommend low-molecular-weight heparin, and from the annual reports of the DHR, we know that this is the most commonly used agent in THA (www.dhr.dk). Even though evidence-based guidelines, including the Danish guidelines, recommend pharmacological prophylaxis for DVT for a minimum of 7–10 days and as long as 35 days in THA and 5–10 days in TKA (www.ortopaedi.dk), the use of pharmacological prophylaxis in the fast-track cohort in this study was shorter—from a maximum of 7 days in the early period to about 3 days in the intermediate and most recent periods. DVT prophylaxis in the fast-track departments starts 6–8 h postoperatively and continues until discharge (Husted et al 2010a, b). In studies involving procedures included in this study, both Husted et al. (2010a) and Jørgensen et al. (2013) demonstrated that short-duration pharmacological prophylaxis together with early mobilization did not increase the risk of DVT in both fast-track THA and fast-track TKA. Our findings strengthen these results, but more information about short duration of pharmacological DVT prophylaxis together with early mobilization is needed.

Large cohort studies have found re-admission risks after THA and TKA ranging from 3.4% to 5.3% (Zmistowski et al. 2011, Wolf et al. 2012). In a recent study that evaluated a fast-track program in the Netherlands, Hartog et al. (2013) found an identical re-admission risk (of 4.5% and 4.4%) 90 days postoperatively before and after implementing a rapid recovery protocol. In a British clinical trial evaluating an enhanced program for hip and knee replacement, identical risks of re-admission were also found in an enhanced recovery program cohort and in a control cohort: 4.8% and 4.7%, respectively (Malviya et al. 2011). The findings by Hartog et al. (2013) and Malviya et al. (2011) where total risk of re-admission was examined after implementing fast-track programs are similar to our results, even though we studied re-admission by looking at risk of re-admission due to infection and risk of re-admission due to thromboembolic events separately. The findings indicate that the risk of re-admission in fast-track settings is at least comparable to what is found in conventional settings, and comparable to that found internationally.

The lack of any difference in the risk of reoperation between the 2 cohorts in all 3 periods found in the present study agrees with the results of 2 clinical trials evaluating implementation of enhanced recovery programs (Malviya et al. 2011, Hartog et al. 2013).

Death within 90 days of joint arthroplasty is rare. The overall risk of less than 0.5% found in our study is comparable to that found in large cohort studies (Wolf et al. 2012, Hunt et al. 2013). In a systematic review, Singh et al. (2011) found a mortality risk in primary THA and TKA of 0.86% and 0.65%, respectively. When comparing risk of mortality, Malviya et al. (2011) found that the 90-day risk of mortality declined from 0.8% to 0.2% after implementation of an enhanced recovery program. Our population-based study could not match such a distinct result, but the RR observed in the recent period (0.82%) in favor of the fast-track cohort is interesting. Future studies will have to show whether this reduced RR of death after implementing a fast-track program is a lasting trend.

We used a population-based design and registries that have been proven valuable for quality development and research (Pedersen et al. 2004, 2012). We are, however, aware of several limitations in our study. We selected the fast-track cohort based on work of the Lundbeck Foundation Center for Fast-track Hip and Knee Replacement and previous publications by Husted et al. (2010b) describing the fast-track program. Although 1 co-writer is affiliated to the Lundbeck Foundation Center for Fast-track Hip and Knee Replacement and to 1 of the 6 departments selected, we do not know if all patients in the fast-track cohort were treated as described in the fast-track program. Our results are dependent on the validity of the ICD codes used in defining the outcome. We have no reason to believe that the completeness of ICD codes depends on the exposure.Also, the validity of the majority of the diagnoses that form the basis of the outcome in this study has been examined in a Danish context. The positive predictive values for the discharge diagnoses of stroke, pneumonia, DVT, PE, urinary tract infection, and AMI have been found to be moderate to high (Johnsen et al. 2002, Thomsen et al. 2006, Ingeman et al. 2010, Severinsen et al. 2010, Thygesen et al. 2011).

The general reduction in LOS indicates that fast-track programs in the treatment of THA and TKA have been widely implemented in Denmark. In this context, the 6 selected fast-track departments can be looked upon as pioneers. This characteristic can also be seen in the different patterns in implant fixation and short duration of pharmacological prophylaxis for DVT. At the same time, it appears that dedicated fast-track departments have been able to optimize the fast-track programs further without any rise in rates of re-admission, reoperation, and mortality. Our results indicate that there is a need for further studies on the influence of fast-track programs on UTI and thromboembolic events.

Supplementary data

Appendix 1 and 2 are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 7096.

Acknowledgments

ENG contributed to the study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of data, and drafting and revision of the article. ABP was the originator of the study. In addition, she contributed to study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, and revision of the manuscript. TBH contributed to the study design, interpretation of data, and revision.

The study was funded by the Health Research Fund of Central Denmark Region. This funding did not lead to any conflicts of interests. One co-writer is affiliated to the Lundbeck Foundation Center for Fast-track Hip and Knee Replacement and to 1 of the 6 selected departments. This affiliation was of no importance to the findings.

References

- Balderi T, Carli F. Urinary retention after total hip and knee arthroplasty . Minerva Anestesiol. 2010;76(2):120–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri A, Vanhaecht K, Van HP, Sermeus W, Faggiano F, Marchisio S, Panella M. Effects of clinical pathways in the joint replacement: a meta-analysis . BMC Med. 2009;7:32. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozic KJ, Maselli J, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK, Vail TP, Auerbach AD. The influence of procedure volumes and standardization of care on quality and efficiency in total joint replacement surgery . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2010;92(16):2643–52. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Online Source 2014 www.dhr.dk

- den Hertog A, Gliesche K, Timm J, Muhlbauer B, Zebrowski S. Pathway-controlled fast-track rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized prospective clinical study evaluating the recovery pattern, drug consumption, and length of stay . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(8):1153–63. doi: 10.1007/s00402-012-1528-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank L. Epidemiology. When an entire country is a cohort . Science. 2000;287(5462):2398–9. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5462.2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartog YM, Mathijssen NM, Vehmeijer SB. Reduced length of hospital stay after the introduction of a rapid recovery protocol for primary THA procedures . Acta Orthop. 2013;84(5):444–7. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.838657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt LP, Ben-Shlomo Y, Clark EM, Dieppe P, Judge A, MacGregor AJ, Tobias JH, Vernon K, Blom AW. 90-day mortality after 409,096 total hip replacements for osteoarthritis, from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales: a retrospective analysis . Lancet. 2013;382(9898):1097–104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61749-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Holm G. Fast track in total hip and knee arthroplasty - experiences from Hvidovre University Hospital . Denmark. Injury (Suppl 5) 2006;37:S31–S35. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(07)70009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Otte KS, Kristensen BB, Orsnes T, Wong C, Kehlet H. Low risk of thromboembolic complications after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty . Acta Orthop. 2010a;81(5):599–605. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.525196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Solgaard S, Hansen TB, Soballe K, Kehlet H. Care principles at four fast-track arthroplasty departments in Denmark . Dan Med Bull. 2010b;57(7):A4166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Jensen CM, Solgaard S, Kehlet H. Reduced length of stay following hip and knee arthroplasty in Denmark 2000-2009 : from research to implementation . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(1):101–4. doi: 10.1007/s00402-011-1396-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingeman A, Andersen G, Hundborg HH, Johnsen SP. Medical complications in patients with stroke: data validity in a stroke registry and a hospital discharge registry . Clin Epidemiol. 2010;2:5–13. doi: 10.2147/clep.s8908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jans O, Kehlet H, Hussain Z, Johansson PI. Transfusion practice in hip arthroplasty—a nationwide study . Vox Sang. 2011;100(4):374–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2010.01428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen SP, Overvad K, Sorensen HT, Tjonneland A, Husted SE. Predictive value of stroke and transient ischemic attack discharge diagnoses in The Danish National Registry of Patients . J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(6):602–7. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00391-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen CC, Jacobsen MK, Soeballe K, Hansen TB, Husted H, Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Hansen LT, Laursen MB, Kehlet H. Thromboprophylaxis only during hospitalisation in fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty, a prospective cohort study . BMJ Open. 2013;3(12):e003965. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlet H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty . Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1600–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlet H, Soballe K. Fast-track hip and knee replacement - what are the issues? . Acta Orthop. 2010;81(3):271–2. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.487237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen K, Sorensen OG, Hansen TB, Thomsen PB, Soballe K. Accelerated perioperative care and rehabilitation intervention for hip and knee replacement is effective: a randomized clinical trial involving 87 patients with 3 months of follow-up . Acta Orthop. 2008;79(2):149–59. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundbeck Foundation Centre for Fast-track Hip and Knee Replacement. Online Source 2003 www.fthk.dk

- Machin JT, Phillips S, Parker M, Carrannante J, Hearth MW. Patient satisfaction with the use of an enhanced recovery programme for primary arthroplasty . Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013;95(8):577–81. doi: 10.1308/003588413X13781990150293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malviya A, Martin K, Harper I, Muller SD, Emmerson KP, Partington PF, Reed MR. Enhanced recovery program for hip and knee replacement reduces death rate . Acta Orthop. 2011;82(5):577–81. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.618911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen A, Johnsen S, Overgaard S, Soballe K, Sorensen HT, Lucht U. Registration in the danish hip arthroplasty registry: completeness of total hip arthroplasties and positive predictive value of registered diagnosis and postoperative complications . Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75(4):434–41. doi: 10.1080/00016470410001213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen AB, Sorensen HT, Mehnert F, Overgaard S, Johnsen SP. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing total hip replacement and receiving routine thromboprophylaxis . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2010;92(12):2156–64. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen AB, Mehnert F, Johnsen SP, Husted S, Sorensen HT. Venous thromboembolism in patients having knee replacement and receiving thromboprophylaxis: a Danish population-based follow-up study . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2011;93(14):1281–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen AB, Mehnert F, Odgaard A, Schroder HM. Existing data sources for clinical epidemiology: The Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register . Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:125–35. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S30050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael M, Jaeger M, van VJ. Easily adoptable total joint arthroplasty program allows discharge home in two days . Can J Anaesth. 2011;58(10):902–10. doi: 10.1007/s12630-011-9565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severinsen MT, Kristensen SR, Overvad K, Dethlefsen C, Tjonneland A, Johnsen SP. Venous thromboembolism discharge diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry should be used with caution . J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(2):223–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh JA, Kundukulam J, Riddle DL, Strand V, Tugwell P. Early postoperative mortality following joint arthroplasty: a systematic review . J Rheumatol. 2011;38(7):1507–13. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Societas Ortopaedica Danica. Online Source 2013 www.ortopaedi.dk

- Thomsen RW, Riis A, Norgaard M, Jacobsen J, Christensen S, McDonald CJ, Sorensen HT. Rising incidence and persistently high mortality of hospitalized pneumonia: a 10-year population-based study in Denmark . J Intern Med. 2006;259(4):410–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, Lash TL, Sorensen HT. The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of Patients. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(83) doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf BR, Lu X, Li Y, Callaghan JJ, Cram P. Adverse outcomes in hip arthroplasty: long-term trends . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2012;94(14):e103. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zmistowski B, Hozack WJ, Parvizi J. Readmission rates after total hip arthroplasty . JAMA. 2011;306(8):825–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.