Abstract

This study investigates the dynamic interplay between teacher-child relationship quality and children’s behaviors across kindergarten and first grade to predict academic competence in first grade. Using a sample of 338 ethnically diverse 5-year-old children, nested path analytic models were conducted to examine bidirectional pathways between children’s behaviors and teacher-child relationship quality. Low self-regulation in kindergarten fall, as indexed by inattention and impulsive behaviors, predicted more conflict with teachers in kindergarten spring and this effect persisted into first grade. Conflict and low self-regulation jointly predicted decreases in school engagement which in turn predicted first grade academic competence. Findings illustrate the importance of considering transactions between self-regulation, teacher-child relationship quality, and school engagement in predicting academic competence.

Keywords: Self-regulation, school engagement, teacher-child relationship quality, academic competence, transactions

The transition into formal schooling entails a period when children shift from predominately interacting with parents and begin interacting with other children and teachers. As such, children are exposed to new influences and settings that shape later experiences, marking this transition a sensitive period for later school success (Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2000). These complex social settings place considerable demands on young children: kindergarteners need to form new relationships, control their impulses, focus and pay attention, communicate their needs appropriately, and engage with learning material. The dynamic interplay between all these key ingredients is critical in determining children’s school readiness. While many studies have examined relations among some of these elements of children’s early schooling to predict future academic achievement, few have investigated these together both concurrently and over time. This study aims to fill this gap by rigorously investigating the dynamic interplay between teacher-child relationship quality and children’s behaviors across the kindergarten and first grade years to predict academic competence in first grade.

Teacher-child relationships

For many young children, kindergarten presents a time for developing bonds with other adults. Although teachers may appear to be transient figures in children’s lives as they progress from grade to grade, teachers play an important role in shaping children’s adjustment to the school context. Teacher-child relationships that exhibit high closeness are characterized by warmth and respect, with children seeing their teachers as a source for security. Conversely, negative teacher-child relationships that are characterized by high conflict appear to pose risks to children’s school success (Pianta, 1999). While teacher-child closeness and conflict are related constructs, they are only moderately correlated, assessing unique aspects of relationship quality as opposed to falling along an underlying continuum.

It is increasingly evident that the quality of the teacher-child relationship matters for children’s social and academic performance in school. Children who are able to successfully navigate early social environments in school and form close bonds with teachers can be set on positive developmental trajectories. Close teacher-child relationships have been positively linked to children’s school engagement (Birch & Ladd, 1997), academic performance, and good work habits (Baker, 2006; Birch & Ladd, 1997; Graziano, Reavis, Keane, & Calkins, 2007; Hamre & Pianta, 2001), and these associations are shown to persist across the elementary school grades (Baker, 2006). Teachers who exhibit strong emotional support in their classrooms have been shown to improve children’s reading achievement from preschool to fifth grade (Pianta, Belsky, Vandergrift, Houts, & Morrison, 2008) and increase phonological awareness from kindergarten to first grade (Curby, Rimm-Kaufman, & Ponitz, 2009). At school entry, highly sensitive teachers have been found to buffer the effects of a negative family context for children who have insecure attachments with their mothers by reducing children’s risk for aggressive behavior (Buyse, Verschueren, & Doumen, 2011). Furthermore, positive interactions with teachers may benefit children who exhibit the highest levels of problematic behaviors at the start of kindergarten (Silver, Measelle, Armstrong, & Essex, 2005). These benefits appear to extend to other domains of adaptive functioning. When comparing a group of children who displayed high levels of aggression, those who experienced warm relationships with their teachers performed better in reading achievement than those who did not (Baker, Grant, & Morlock, 2008).

However, children differ in their ability to connect with teachers and capitalize on these experiences that promote school success. In particular, conflict with teachers may negatively impact children’s sense of belonging and perception of academic competence, as well as the motivation or engagement necessary to excel in school (Spilt, Hughes, Wu, & Kwok, 2012). In fact, relationships characterized by conflict have been associated with greater school avoidance, lower school engagement, less self-directedness, and less cooperative participation (Birch & Ladd, 1997). Teachers who perceive young children to be aggressive, argumentative or clingy are more likely to be referred for special services or be retained (Pianta, Steinberg, & Rollins, 1995); this provides more evidence of the deleterious consequences for children that experience conflictual relationships with their teachers. Furthermore, kindergarten teacher-child relationships characterized by relational negativity predicted lower student grades, standardized test scores and work habits through elementary school, and continued to uniquely predict behavioral difficulty through middle school (Hamre & Pianta, 2001). Hamre & Pianta’s (2001) findings highlight the long reach early teacher-child relationship conflict may have on children’s future academic success.

Bidirectional transactions between teacher-child relationship quality and child functioning

Extending a transactional model of development (Sameroff & MacKenzie, 2003) to a school context, it is theorized that children’s behaviors and the classroom environment, indexed in this study by relationship quality with teachers, interact through bidirectional processes. Over time, the interplay between teacher-child relationship quality and children’s behaviors may form patterns that serve as both inputs and outcomes to children’s development (Arnold, McWilliams, & Arnold, 1998; Downer, Sabol, & Hamre, 2010). To illustrate, Doumen and colleagues (2008) found empirical evidence that children’s aggressive behavior displayed at kindergarten onset led to greater teacher-child conflict by the middle of the school year, which in turn led to more aggressive behavior by those children at the end of the year. Some researchers argue that negative child characteristics largely drive conflict with teachers since conflict tends to be measured by teachers’ perceptions of relationship quality and is comprised of reactive teacher behavior resulting from dealing with challenging behavior (Silver, et al., 2005).

Children who perceive their teachers to be accepting and caring are more likely to internalize learning and prosocial goals valued by their teachers (Wentzel, 1999). By displaying expected behavior in the classroom, positive interactions with teachers are theorized to further reinforce acceptable behavior. Yet, empirical evidence suggests that teacher-child closeness is only moderately associated with child characteristics (Jerome, Hamre, & Pianta, 2009). The degree to which children and teachers can connect may be more indicative of a dynamic pattern building on strengths of both teacher and child, rather than a reactive pattern to child characteristics as is conceptualized for teacher-child conflict (Spilt, et al., 2012).

Predictors of teacher-child relationship quality and school readiness

There is general consensus that early experiences in school are critical for shaping children’s future academic careers. Children who achieve academically early on continue to show achievement gains; those who encounter learning problems face continuing negative consequences that persist over time (Perry, Donohue, & Weinstein, 2007). To enhance children’s early school experiences, it is essential to better understand competencies that promote learning and positive relationship quality with teachers. In particular, two areas of children’s functioning that are thought to predict school readiness and academic achievement are children’s self-regulation skills (Blair & Razza, 2007; Duncan et al., 2007; McClelland et al., 2007) and school engagement (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004; Ladd & Dinella, 2009).

Self-regulation

Self-regulation is a broad, multi-dimensional construct consisting of cognitive and behavioral processes that allow individuals to maintain optimal levels of emotional, motivational, and cognitive arousal for positive adjustment and adaptation (Blair & Diamond, 2008). Self-regulatory capacities are implicated in the ability to control impulses and pay attention, behaviors that are relevant for school success. Upon entering kindergarten, children are faced with a new set of challenges in the classroom: they need to learn how to be independent from their caregivers, navigate social interactions with other children, pay attention for longer periods of time, and adhere to a classroom routine (Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2000).

Difficulties with self-regulation may be most easily observed as impulsive and inattentive behavior in the classroom setting. Both of these behaviors may be seen as markers of low inhibitory control, particularly response inhibition in the context of impulsive behaviors and interference suppression in the context of inattention. Furthermore, Barkley (1997) theorized that inattention and impulsivity emerge when children face challenges with emotional self-regulation and working memory. Low performance on laboratory tasks measuring self-regulation have been associated with higher incidence of inattention and impulsivity in young children (Olson, Sameroff, Kerr, Lopez, & Wellman, 2005). Moreover, children who lack the attentional and inhibitory control processes necessary to focus on educational material tend to exhibit challenges learning and engaging with classroom activities. These challenges potentially place them at risk for reduced academic achievement as they progress through school (Blair, 2002). Such an association was evidence from six longitudinal studies suggesting that children’s attentional skills in kindergarten, such as task persistence, predicted math and reading achievement in third grade (Duncan, et al., 2007).

However, inattention and impulsive behaviors do not only reflect low levels of self-regulation skills. They are multiply determined and can be socially constructed. Indeed, research shows that relationship quality is important and children’s ability to self-regulate contributes to how they are viewed by others, particularly teachers (Myers & Pianta, 2008). Recent empirical studies provide evidence that both parent and teacher survey measures of self-regulation skills predict greater teacher-child closeness (Liew, Chen, & Hughes, 2010; Rudasill & Rimm-Kaufman, 2009; Valiente, Swanson, & Lemery-Chalfant, 2012) and parent reported self-regulation skills predict less teacher-child conflict (Myers & Morris, 2009). Conversely, children who display inattention and impulsivity may experience difficulties engaging in positive relationships with teachers (Barkley, 1998). Teachers may view children who lack self-regulatory capacities as intentionally misbehaving, causing teachers to react in a disciplinary fashion and engage in more conflict with these children. Beyond disciplining, teachers may only engage with these children in an instructional format, affording fewer opportunities for mutual exchange and positive interaction (Silva et al., 2011). Furthermore, the presence of challenging behaviors may be more salient and consuming to teachers, disrupting learning opportunities for all children within the classroom.

School engagement

School engagement has often been studied as a possible antecedent of academic achievement. This construct has been broadly conceptualized in three domains: behavioral (i.e., participation in extracurricular activities), emotional (i.e., positive and negative feelings and reactions towards school, teachers, peers), or cognitive (i.e., willingness to invest in learning difficult skills and comprehension of complex ideas) (Fredricks, et al., 2004). Young children’s school engagement may be most manifested through an examination of emotional school engagement. A significant body of evidence supports the idea that emotional school engagement is an important predictor for academic functioning (Ladd, Buhs, & Seid, 2000; Ladd & Dinella, 2009). When children exhibit positive attitudes toward school, they are more likely to engage in classroom activities that are designed to promote academic and social competencies (Ladd, et al., 2000). Similarly, children who demonstrate an orientation toward learning and respond to classroom challenges in a mastery-oriented fashion tend to display patterns of motivation that predict positive school adjustment (Heyman & Dweck, 1992).

Teachers play a role in enhancing children’s school enjoyment. Within a context of positive teacher-child relationships, children likely feel more confident in their abilities and motivated to participate in classroom activities (Silva, et al., 2011). Further, school engagement has been seen as mediating the association between teacher-child relationships and academic success in young children (Hughes, Luo, Kwok, & Loyd, 2008). Applying a transactional framework, children’s school engagement may also predict subsequent teacher-child relationship quality. However, in a recent large-scale study, school engagement in first grade was unrelated to teacher-child relationship quality in fourth grade (Archambault, Pagani, & Fitzpatrick, 2013).

Children’s school engagement is thought to be supported by self-regulation. Children who are able to control their emotions and behaviors tend to feel more comfortable in school (Valiente, Lemery-Chalfant, & Swanson, 2010). In contrast, children who lack self-regulation may feel socially alienated and withdraw from classroom participation (Valiente, et al., 2012). Thus, children who display better self-regulation skills may elicit more positive interactions with teachers which in turn promote their enjoyment in school and other learning-related activities, indicating that teacher-child relationship quality may serve as a mediator in this association (Silva, et al., 2011). Examining how teacher-child relationship quality and children’s self-regulation may promote school engagement is therefore critical in understanding possible antecedents to academic competence and is a central aim of this study.

Gender differences

A large body of literature has documented gender differences in how teachers perceive relations with children: teachers report more closeness with girls and more conflict with boys (Birch & Ladd, 1998; Hamre & Pianta, 2001). Boys have also been found to be more distractible and active (Mendez, McDermott, & Fantuzzo, 2002; Walker, Berthelsen, & Irving, 2001) and less persistent on tasks than girls (Walker, et al., 2001), indicating that, on average, boys tend to experience more issues with self-regulatory skills. Research has also shown that girls exhibit more school engagement and boys exhibit more school avoidance (Roorda, Koomen, Spilt, & Oort, 2011; Silva, et al., 2011). All of this evidence suggests the importance of controlling for gender differences at kindergarten entry.

An integrative view of children’s school functioning

While making significant conceptual and empirical advancements to our understanding of how teacher-child conflict and closeness predict children’s concurrent and prospective behavioral and academic functioning, much of the extant literature has not examined the unique contribution of conflict over and above teacher-child closeness (Arnold, et al., 1998; Doumen, et al., 2008; Hamre & Pianta, 2001) or vice versa (Buyse, et al., 2011). Some studies have examined the joint contributions of both teacher-child closeness and conflict by aggregating both constructs into one measure of overall relationship quality (Baker, 2006; Hughes, et al., 2008; O’Connor & McCartney, 2007) but this methodology does not allow for an examination of whether underachievement or behavior problems are a result of conflict, deterioration of closeness, or both (Spilt, et al., 2012). Notably, Silver et al. (2005) accounted for both when predicting growth in behavior problems from kindergarten to third grade, but did not control for concurrent relations between child behavior and relationship quality in first and third grade. The current study addressed these limitations by accounting for bidirectional influences of both conflict and closeness on children’s school adjustment over time.

Given the interplay between teachers and children during this rich period of development, studies examining the effect of teacher-child relationship quality on children’s functioning must also consider the individual attributes that a child brings into the school environment and how these attributes shape transactions between teacher-child relationship quality and the child. Recent literature has acknowledged this, but the majority of studies have only investigated children’s externalizing behavior as an outcome (Leflot, van Lier, Verschueren, Onghena, & Colpin, 2011; Stipek & Miles, 2008) while others have only examined transactions within the course of one school year (Doumen, et al., 2008). Building on this research, the current study examined indices of both positive and negative behavior longitudinally, investigating the importance of children’s self-regulation and school engagement in predicting teacher-child relationship quality and later academic competence.

Relevant for this study, Eisenberg, Valiente, & Eggum (2010) proposed a conceptual model linking children’s self-regulation and academic achievement. They posit that self-regulatory skills predict relationship quality with others (e.g., teachers, peers) and adjustment (e.g., problem behaviors, social competence). These two pathways are theorized to affect children’s school engagement, such that issues with relationship quality or maladjustment will lead to reduced school engagement. This, in turn, predicts lower academic achievement. Thus, relationship quality, appropriate behavior, and school engagement are conceptualized as accounting for indirect pathways between self-regulation and academic functioning. The current study provided an opportunity to empirically test these theorized linkages and to expand beyond this conceptual framework by examining relations among self-regulation, teacher-child relationship quality, school engagement, and academic competence concurrently and over time to tease apart dynamic processes during this sensitive period of development.

The current study

Extending prior work investigating transactional processes between children and teacher-child relationship quality (Doumen, et al., 2008; Leflot, et al., 2011; Rudasill & Rimm-Kaufman, 2009), this study had three goals: (1) To examine how child gender predicts initial levels of children’s functioning (as indexed by inattention and impulsive behaviors, school engagement, and teacher-child relationship quality) at school entry; (2) To investigate whether children and the teacher-child relationship quality engage in bidirectional transactions across the kindergarten year to influence later relationship quality and children’s functioning; and (3) To explore how kindergarten children’s functioning and relationships with their teachers predict later behavior, teacher-child relationship quality, and academic competence in first grade.

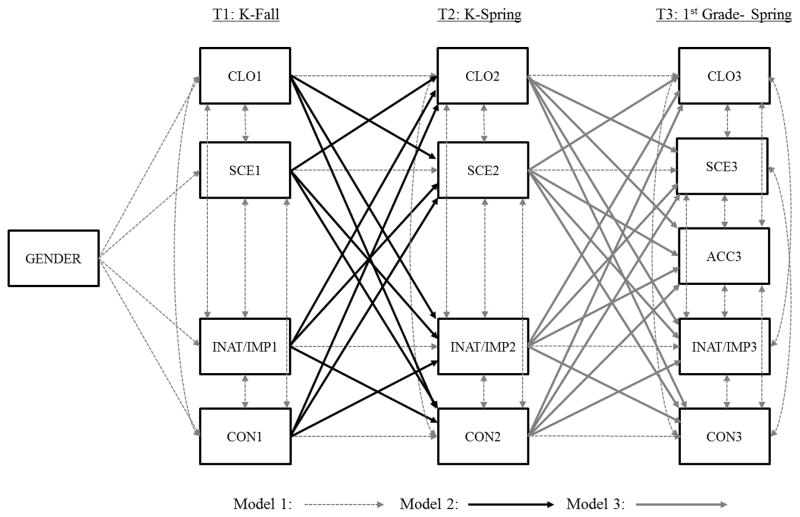

Central hypotheses were systematically evaluated using a series of nested path analytic models and successive nested model comparisons (see Figure 1). Model 1 depicts a continuity model which examines the stability of each construct across time, with gender predicting children’s behavior and teacher-child relationship quality at kindergarten entry. We hypothesized that gender at the start of kindergarten would relate to teacher-child relationship quality and children’s inattention and impulsive behaviors and school engagement in the classroom. Specifically, it was expected that boys might experience more conflict with teachers whereas girls might experience more closeness. We also hypothesized that girls would be more engaged in school and that boys would exhibit more inattention and impulsive behaviors.

Figure 1.

A summary of the freely estimated paths in hierarchically nested path analytic models. Notes. Numbers denote time point of data collection (1 = kindergarten fall, 2 = kindergarten spring, 3 = first grade spring). Model 1 represents a baseline comparison model of longitudinal stability with gender predicting this stability, after accounting for within-time point, cross-domain covariation. Model 2 represents diagonal pathways from T1 to T2. Model 3 adds diagonal pathways from T2 to T3. All models include paths from prior models in sequence.

CLO= closeness; CON= conflict; SCE= school engagement; INAT/IMP= inattention/impulsivity; ACC= academic competence

Across three time points, each construct was assessed using the same measures. However, children were exposed to different teachers in kindergarten and first grade. Despite changes in informants for teacher-reported domains, it was expected that significant longitudinal stability would emerge. Considering recent work by Jerome and colleagues (2009), we hypothesized that the stability of teacher-child conflict would be stronger than closeness. Since extant research indicates that children’s inattention and impulsive behaviors, school engagement, and teacher-child closeness and conflict are all related concurrently, this model also accounted for within time point covariation in order to detect longitudinal spillover effects. Cross-sectional research reviewed earlier provides robust evidence for significant within-time covariation among these different domains of adaptation.

Model 2 examined cross-domain transactions across kindergarten to investigate whether there are bidirectional transactions between teacher-child relationship quality and children’s behaviors. Given theoretical and empirical evidence suggesting teacher-child relationship quality and children’s behavior influence each other to predict later child outcomes, we expected to find reciprocally influential relations from teacher-child relationship quality to children’s functioning and vice versa. In particular, we hypothesized bidirectional transactions between children’s school engagement and teacher-child closeness, and bidirectional transactions between teacher-child conflict and children’s inattention and impulsive behaviors.

Finally, Model 3 examined cross-domain transactions to understand whether kindergarten processes affected children’s functioning and teacher-child relationship quality in first grade. We hypothesized that school engagement at the end of kindergarten would predict academic competence in first grade given the mediating pathways that Eisenberg and colleagues (2010) have posited. Also, given the empirical evidence linking both teacher-child relationship quality and behavior problems with academic achievement, we expected to find a relation from closeness and conflict, as well as inattention and impulsivity, to academic competence.

This investigation extended the current literature on school readiness and teacher-child relationship quality. Importantly, it combined research in the areas of self-regulation, teacher-child interactions, and school engagement, and examined how these domains predict child academic competence in an empirically rigorous way. Prior work has examined different elements of this model; this study included variables that were theoretically linked in order to provide a more holistic picture of child school functioning at the transition to elementary school.

Nested path analytic comparisons offered the best available method to empirically evaluate whether or not there were bidirectional transactions of child behaviors and teacher-child relationship quality across the kindergarten year (Model 2) and into first grade (Model 3). The rigor of this methodology is due to the fact that these pathways are examined after accounting for longitudinal stability and within-time point covariation (Model 1). As such, pathways linking domains across time can be attributed to longitudinal processes because the cross-sectional cross-domain associations are already controlled for, allowing us to select a model that most parsimoniously fit the data. This extends prior research that finds a significant association between earlier teacher-child relationship quality and later academic achievement, but fails to examine whether this association is due to longitudinal processes or the processes that are happening concurrently at the beginning or the end of the study period.

Method

Participants

The sample was comprised of 338 kindergarten children (M age at kindergarten entry = 5.31 years; SD = 0.32; range = 4.75 – 6.28 years; 175 males, 163 females) who participated in a longitudinal study examining child mental and physical health, school functioning, biological responses to adversity, and social dominance. Participants were recruited from 29 classrooms in 6 public schools in the Bay Area, California and data were collected across three waves in 2004, 2005, and 2006. The sample of children was highly diverse, with 43% being identified as Caucasian, 19% as African American, 11% as Asian, 4% as Latino, 22% as multi-ethnic, and 2% being described as “other”. Ten percent of primary caregivers described themselves as single parents and 28% of children had at least one immigrant parent. Total annual household income varied greatly, ranging from 4% of the sample earning less than $10,000 to 0.3% earning more than $400,000 (M = $60,000 – $79,000; Median = $80,000 – $99,999) which is representative of the population in the Bay Area. Primary caregivers’ education level also varied greatly, with 8% obtaining a high school degree or less and 45% having earned a graduate or professional degree.

Participating teachers from the 29 classrooms were predominately female (76%) and Caucasian (82%). Teachers identified themselves as 11% Asian, 4% African American, and 4% self-described as “other”. Mean age was 52 years (SD = 10.5) and most of the teachers were veteran teachers with 62% having taught kindergarten for more than three years. Fifty-five percent had a Bachelor’s degree, 31% had a Master’s degree, and 14% had some other type of credentialing.

Procedures

Data were collected from participants at three time points: T1- kindergarten fall, T2- kindergarten spring, and T3- first grade spring. Before collecting any data, parents provided informed consent to participate in the study. Parents were asked to provide information concerning their demographics, family functioning, and child functioning through a series of questionnaires that were mailed to their home. Compensation consisted of $50 per completed parent survey. Teachers were asked to fill out questionnaires about each participating child’s functioning and were compensated $15 per child for each completed survey. At Time 1, teachers completed responses between October and December, providing sufficient time to get to know the children.

Measures

For this study, both parents and teachers reported on children’s levels of impulsivity and inattention, school engagement, and academic competence to capture multiple perspectives of children’s behavior across two different contexts (i.e., home and school) (Kraemer et al., 2003) and teachers reported on the teacher-child relationship quality. Table 1 provides descriptive and reliability statistics for the current sample (e.g., means, standard deviations, number of items, Cronbach’s alpha) for all measures by informant and across all time periods.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Predictors and Outcomes

| Domains/Scales | Scale | # of Items | Kindergarten Fall

|

Kindergarten Spring

|

First Grade Spring

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | % Missing | α | r | M | SD | % Missing | α | r | M | SD | % Missing | α | r | |||

| Teacher-child relationship quality | |||||||||||||||||

| Closeness | 1–5 | 5 | 4.17 | 0.85 | 0.0 | 0.89 | 4.28 | 0.81 | 3.0 | 0.91 | 4.18 | 0.81 | 12.4 | 0.90 | |||

| Conflict | 1–5 | 5 | 1.51 | 0.84 | 0.0 | 0.89 | 1.59 | 0.92 | 3.0 | 0.91 | 1.62 | 0.88 | 12.7 | 0.88 | 0.37 *** | ||

| Self-regulation | 0.39 *** | 0.49 *** | |||||||||||||||

| P-HBQ | |||||||||||||||||

| Inattention | 0–2 | 6 | 0.52 | 0.40 | 13.3 | 0.81 | 0.56 | 0.41 | 16.9 | 0.80 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 35.8 | 0.82 | |||

| Impulsivity | 0–2 | 9 | 0.58 | 0.36 | 13.3 | 0.79 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 16.9 | 0.83 | 0.6 | 0.38 | 35.8 | 0.82 | |||

| T-HBQ | |||||||||||||||||

| Inattention | 0–2 | 6 | 0.32 | 0.44 | 0.0 | 0.88 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 3.0 | 0.88 | 0.4 | 0.53 | 12.4 | 0.92 | |||

| Impulsivity | 0–2 | 9 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.0 | 0.91 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 3.0 | 0.91 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 12.4 | 0.92 | 0.37 *** | ||

| School engagement | 0.17 ** | 0.27 *** | |||||||||||||||

| P-HBQ | 1–4 | 8 | 3.73 | 0.37 | 13.6 | 0.83 | 3.66 | 0.44 | 16.9 | 0.87 | 3.59 | 0.48 | 35.5 | 0.87 | |||

| T-HBQ | 0–2 | 8 | 1.80 | 0.28 | 0.0 | 0.81 | 1.79 | 0.30 | 3.0 | 0.84 | 1.75 | 0.33 | 12.4 | 0.86 | |||

| Academic competence | 0.66 *** | ||||||||||||||||

| P-HBQ | 1–7 | 8 | 5.44 | 1.07 | 35.8 | 0.91 | |||||||||||

| T-HBQ | 1–5 | 5 | 3.49 | 0.97 | 12.7 | 0.96 | |||||||||||

Notes. α = Cronbach’s alpha; r = correlation between scales used to create parent & teacher composite ratings; P-HBQ: parent report on the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire; T-HBQ: teacher report on the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire.

Teacher-child relationship quality

Teacher-child relationship quality was reported at all three time points by teachers using a shortened version of the Student-Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS; Pianta, 1996). The 10-item version of the STRS assessed teachers’ perceptions of the level of closeness and conflict they experienced with individual children using a 5-point Likert-style rating scale (1 = definitely does not apply and 5 = definitely applies). The 5-item closeness subscale included items such as “You share an affectionate, warm relationship with this child” and “This child openly shares his/her feelings and experiences with you.” The 5-item conflict subscale included items such as “You and this child always seem to be struggling with each other” and “This child easily becomes angry with you.”

Child functioning

Children’s functioning was assessed in three domains: inattention and impulsivity, school engagement, and academic competence. Parents and teachers reported on these domains using scales from the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ; Armstrong, 2003). The HBQ contains parallel measures to assess children in a multi-informant, multi-domain approach. Parent and teacher scores were re-scaled and averaged to create composites for each domain at each time point in order to capture assessments of children’s behaviors both at home and in school and equally weight both contexts.

Inattention and impulsive behaviors were reported at all three time points by parents and teachers via a composite of the mean of the inattention and impulsivity subscales from the HBQ (Armstrong, 2003). Both subscales were rated using the following categories (0 = never/not true, 1 = sometimes or somewhat true, 2 = often or very true). Examples of items for the inattention subscale included “Distractible, has trouble sticking to one activity”, “Can’t concentrate, can’t pay attention for long”, and “Has difficulty following directions or instructions.” The impulsivity subscale included items such as “Can’t stay seated when required to do so”, “Has difficulty awaiting turn in games or groups”, and “Interrupts, blurts out answers to questions too soon.”

School engagement was reported at all three time points by parents and teachers using the school engagement subscale from the HBQ (Armstrong, 2003) which assessed both intrinsic motivation and school liking. Parents reported on an 8-item scale that was rated using the following categories (1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = somewhat, 4 = quite a bit). Parent items captured attitudes and emotions toward school and included items such as “Is excited about school”, “Is frustrated about school”, and “Is interested in school.”

Teachers reported on a slightly different 8-item scale that was rated using the following categories (0= doesn’t apply, 1= sometimes applies, 2= certainly applies). In addition to school liking, teacher items included behaviors towards school specifically observed in the classroom. Examples of items included “Is cheerful at school” and “Seems bored at school.”

Academic competence was assessed by parents and teachers using the academic competence subscale from the HBQ used to assess school functioning. This scale taps into children’s abilities in math and reading. Research suggests that parents utilize relative comparisons to evaluate children’s ability levels (Miller, 1995); therefore, parents reported on an 8-item scale using a Likert-style rating scale that compared their children’s abilities with other children (1 = not at all/much worse than other children and 7 = very good/much better than other children). Example of items included “In comparison to other children, how difficult is it for your child to read?” and “In comparison to other children, how would you rate your child in math?” Teachers reported on a slightly different 5-item scale that read more like a report card asking teachers to rate children in different subject areas, using a Likert-style rating scale (1 = poor/well below grade level and 5 = excellent, well above grade level). Teacher rated academic competence was assessed with items such as “How would you evaluate this child’s current school performance in math-related skills/reading-related skills/spelling/overall?” Given that academic competence is an emerging domain in early schooling with children’s skills becoming more differentiated once the classroom activities become more academic, measurement of academic competence was included only at the end of first grade in order to both detect variability on this global measure of children’s ability and maintain a more parsimonious model.

Data analytic plan

Data preparation

The rate of missing cases varied across variables (range = 3% – 35.8%). Due to the longitudinal nature of the study, response rates decreased over time, particularly as children transitioned from kindergarten to first grade (see Table 1 for percent of missing cases by measure and informant). Missing values in this data were considered to be ignorable (i.e., missing at random). As such, path analyses were conducted using maximum likelihood estimation which permitted statistical inference to use all available data for the 338 participants (Schafer, 1997; Schafer & Graham, 2002).

Analytic Plan

Analyses were conducted using nested path analysis models in Mplus 5.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007). In the conceptual model, gender was proposed as an exogeneous, observed variable predicting child functioning and teacher-child relationship quality in the fall of kindergarten and is included as a control. Child gender was reported by parents as part of a demographic questionnaire completed in the fall of the kindergarten year. To account for non-normality of some variables, we used robust maximum likelihood estimator to account for this (MLR option in Mplus). All models accounted for clustering of children within classrooms by specifying the TYPE= COMPLEX analysis command in Mplus.

To evaluate absolute model fit between the data and the models, we used the following fit indices: comparative fit index (CFI; values ≥ .95 indicate good model fit), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; values ≥ .95), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; values ≤ .06). Failure to meet one of these fit indices indicates poor model fit although there is considerable debate in the field as to how to evaluate model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Marsh, Hau, & Wen, 2004) with the above guidelines perhaps being too stringent to strictly evaluate goodness of fit.

Relative model fit was evaluated using chi-square difference tests between sequential models. A scaling constant, c coefficient, was applied to determine whether a model with more estimated parameters (i.e., less parsimonious) resulted in a better relative fit to the data than the more parsimonious one. If the chi-square difference test was significant indicating that additional pathways improved the model fit, the more complex model was selected (Satorra, 1999).

Results

Bivariate relations

Bivariate relations revealed associations between the gender predictor at kindergarten entry and domains across time (see Table 2). At kindergarten entry, girls experienced closer relationships with teachers and more school engagement across all three time points; boys experienced more conflict with teachers and more impulsive behavior and inattention. Gender was not correlated with first grade academic competence.

Table 2.

Zero-order Correlations Between Variables Included in the Path Analyses

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gender | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 2 CLO1 | 0.17*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 3 CON1 | −0.17*** | −0.23*** | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 4 INAT/IMP1 | −0.37*** | −0.14* | 0.57*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 5 SCE1 | 0.19*** | 0.33*** | −0.41*** | −0.38*** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 6 CLO2 | 0.19*** | 0.63*** | −0.14** | −0.10 | 0.22*** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 7 CON2 | −0.22*** | −0.18*** | 0.72*** | 0.52*** | −0.31*** | −0.32*** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 8 INAT/IMP2 | −0.38*** | −0.14* | 0.52*** | 0.84*** | −0.33*** | −0.20*** | 0.61*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 9 SCE2 | 0.20*** | 0.28*** | −0.43*** | −0.46*** | 0.57*** | 0.44*** | −0.57*** | −0.46*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 10 CLO3 | 0.28*** | 0.29*** | −0.09 | −0.12* | 0.17*** | 0.25*** | −0.03 | −0.11 | 0.18*** | 1.00 | ||||

| 11 CON3 | −0.24*** | −0.16** | 0.59*** | 0.48*** | −0.27*** | −0.19*** | 0.61*** | 0.54*** | −0.41*** | −0.27*** | 1.00 | |||

| 12 INAT/IMP3 | −0.28*** | −0.12 | 0.48*** | 0.69*** | −0.22*** | −0.14* | 0.49*** | 0.74*** | −0.32*** | −0.11 | 0.62*** | 1.00 | ||

| 13 SCE3 | 0.24*** | 0.15* | −0.28*** | −0.24*** | 0.31*** | 0.17** | −0.27*** | −0.23*** | 0.50*** | 0.41*** | −0.53*** | −0.45*** | 1.00 | |

| 14 ACC3 | 0.01 | 0.13* | −0.17** | −0.17* | 0.26*** | 0.15* | −0.11 | −0.16* | 0.27*** | 0.13 | −0.12 | −0.30*** | 0.37*** | 1.00 |

| N | 338 |

Notes: Numbers denote time point of data collection (1 = kindergarten fall, 2 = kindergarten spring, 3 = first grade spring). Gender is coded: 1= girls, 0= boys. CLO = teacher-child closeness; CON = teacher-child conflict; INAT/IMP = inattention/impulsivity; SCE = school engagement; ACC = academic competence.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Teacher-child closeness was negatively correlated with conflict at all three time points, albeit moderately, signifying that this measure was tapping into different aspects of the relationship. Those children that experienced more closeness with teachers in kindergarten also demonstrated more school engagement across all waves, fewer issues with impulsivity and inattention across the kindergarten year, and more academic competence in first grade. Interestingly, more closeness with first grade teachers was positively correlated with school engagement in first grade but not correlated with inattention and impulsivity or academic competence in first grade. More conflict in first grade was related to greater levels of inattention and impulsivity, and less school engagement. More conflict with teachers was associated with less school engagement and more inattention and impulsivity across all waves of data collection, but was not associated with academic competence in first grade.

Nested path analyses

Fit statistics and model comparisons for hierarchically nested path analysis models are presented in Table 3. The continuity and within time covariation model (Model 1), which included gender as a predictor at the start of kindergarten, evidenced relatively good fit to the data (CFI = .933; TLI = .893; RMSEA = .069). The addition of cross-domain pathways from kindergarten fall to kindergarten spring (Model 2) further improved the overall model fit (CFI = .953; TLI = .905; RMSEA = .064). The difference test of relative fit indicated this was a significant difference: Δ χ2 (45) = 108.05, p < .001. Model 3 added cross-domain pathways to predict outcomes in first grade and indicated even better overall model fit (CFI = .974; TLI = .919; RMSEA = .060) indicating excellent model fit on two of the three fit indices and good model fit on the TLI. As this was significantly better than Model 2, Δ χ2(29) = 63.84, p < .001, we deemed Model 3 to be the best fit model to this data.

Table 3.

Fit Statistics and Model Comparisons for Hierarchically Nested Path Analyses

| Path analyses

|

Difference test of relative fit

|

Absolute fit statistics

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | # cross domain paths | df | c | chi-sq | Model comparison | cd | Chi-sq(Diff) | df(Diff) | p-value | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

| 1 | 4 | 57 | 1.197 | 147.535 | 0.933 | 0.893 | 0.069 | |||||

| 2 | 16 | 45 | 1.162 | 108.054 | 1 vs. 2 | 1.328 | 38.43 | 12 | 0.000 | 0.953 | 0.905 | 0.064 |

| 3 | 32 | 29 | 1.088 | 63.844 | 2 vs. 3 | 1.296 | 43.28 | 16 | 0.000 | 0.974 | 0.919 | 0.060 |

Notes: c = weighting constant for computing the chi-square statistic using robust estimation method; cd = weighting constant for the difference between two chi-square values using robust estimation method. CFI = comparative fix index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index; RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation.

Model 1: Continuity across 3 time points, within time correlations at each time point, with gender predicting T1

Model 2: Adds diagonal pathways from T1 to T2, with gender predicting T1

Model 3: Adds diagonal pathways from T2 to T3, with gender predicting T1

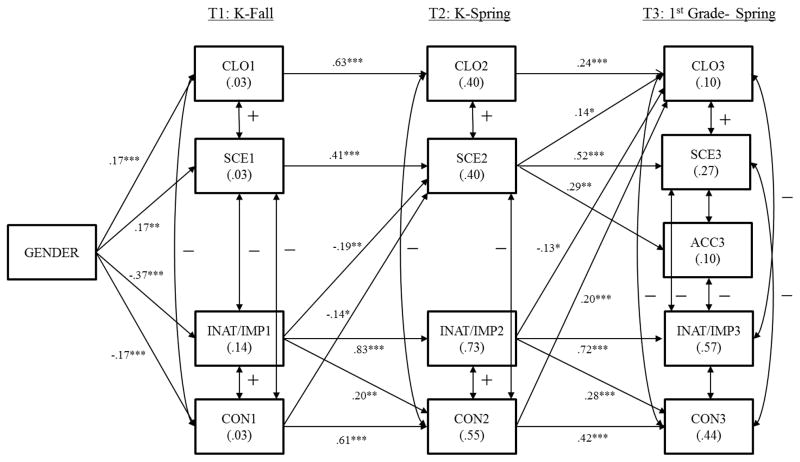

Standardized path coefficients for the best fitting model (Model 3) are presented in Figure 2. Standardized, as well as unstandardized, path coefficients are shown below, with the p-values presented from the standardized model results. Results show that child gender predicted both child behaviors and teacher-child relationship quality. Boys experienced more conflict with teachers (B = −.29, β = −.17, p < .001) and more inattention and impulsivity (B = −.24, β = −.37, p < .001). Girls experienced closer relationships with teachers (B = .29, β = .17, p < .001) and more school engagement (B = .13, β = .17, p < .01). The stability coefficients were consistently positive and significant across all domains.

Figure 2.

Standardized path coefficients for significant paths of final model (Model 3). Notes. R2 values are denoted in parentheses. Numbers denote time point of data collection. Within-time associations are represented by +/− (please refer to Table 4 for coefficients). CLO= closeness; CON= conflict; SCE= school engagement; INAT/IMP= inattention/impulsivity; ACC= academic competence. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

χ2 (29) = 63.84; CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.06

There was significant within-time covariation between all domains (standardized coefficients are presented in Table 4). At all three time points, significant covariation emerged across domains in the same pattern with one exception: closeness was positively related to school engagement at all three time points (kindergarten fall: B = .10, β = .32, p < .001; kindergarten spring: B = .10, β = .42, p < .001; 1st grade: B = .14, β = .38, p < .001) but negatively related to inattention and impulsivity only at the end of 1st grade (B = −.02, β = −.11, p < .05). Conflict was negatively related to school engagement (kindergarten fall: B = −.13, β = −.40, p < .001; kindergarten spring: B = −.10, β = −.42, p < .001; 1st grade: B = −.15, β = −.47, p < .001) and positively related to inattention and impulsivity (kindergarten fall: B = .15, β = .60, p < .001; kindergarten spring: B = .05, β = .40, p < .001; 1st grade: B = .06, β = .42, p < .001). School engagement was negatively related to inattention and impulsivity, but not at the end of kindergarten (kindergarten fall: B = −.04, β = −.36, p < .001; 1st grade: B = −.05, β = −.45, p < .001). As expected, teacher-child closeness and conflict were negatively related (kindergarten fall: B = −.14, β = −.21, p < .001; kindergarten spring: B = −.16, β = −.40, p < .01; 1st grade: B = −.15, β = −.29, p < .001). Academic competence in first grade was positively related to school engagement (B = .09, β = .27, p < .001) and negatively related to inattention and impulsivity (B = −.05, β = −.28, p < .001). Notably, there was no significant within-time covariation between first grade teacher-child relationship quality and academic competence.

Table 4.

Within Time Associations for Model 3

| Time | Estimated Path | β SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| K-Fall | Clo1 ↔ Sce1 | 0.316 (0.074) *** | 0.000 |

| Clo1 ↔ Inat/Imp1 | −0.060 (0.067) | 0.373 | |

| Clo1 ↔ Con1 | −0.205 (0.047) *** | 0.000 | |

| Sce1 ↔ Inat/Imp1 | −0.358 (0.067) *** | 0.000 | |

| Sce1 ↔ Con1 | −0.401 (0.055) *** | 0.000 | |

| Inat/Imp1 ↔ Con1 | 0.602 (0.052) *** | 0.000 | |

| K-Spring | Clo2 ↔ Sce2 | 0.415 (0.086) *** | 0.000 |

| Clo2 ↔ Inat/Imp2 | −0.239 (0.128) † | 0.061 | |

| Clo2 ↔ Con2 | −0.396 (0.137) ** | 0.004 | |

| Sce2 ↔ Inat/Imp2 | −0.217 (0.136) | 0.109 | |

| Sce2 ↔ Con2 | −0.420 (0.093) *** | 0.000 | |

| Inat/Imp2 ↔ Con2 | 0.399 (0.092) *** | 0.000 | |

| 1st grade-Spring | Clo3 ↔ Sce3 | 0.378 (0.064) *** | 0.000 |

| Clo3 ↔ Inat/Imp3 | −0.105 (0.052) * | 0.044 | |

| Clo3 ↔ Acc3 | 0.046 (0.060) | 0.445 | |

| Clo3 ↔ Con3 | −0.294 (0.059) *** | 0.000 | |

| Sce3 ↔ Inat/Imp3 | −0.453 (0.079) *** | 0.000 | |

| Sce3 ↔ Acc3 | 0.273 (0.062) *** | 0.000 | |

| Sce3 ↔ Con3 | −0.466 (0.057) *** | 0.000 | |

| Inat/Imp3 ↔ Acc3 | −0.278 (0.064) *** | 0.000 | |

| Inat/Imp3 ↔ Con3 | 0.424 (0.061) *** | 0.000 | |

| Con2 ↔ Acc3 | −0.023 (0.057) | 0.689 |

Notes: β = standardized path coefficient. Standard errors are in parentheses. Numbers denote time point of data collection (1 = kindergarten fall, 2 = kindergarten spring, 3 = first grade spring). Clo = closeness; Sce = school engagement; Inat/Imp = inattention/impulsivity; Acc = academic competence; Con = conflict.

Examining transactional patterns across the kindergarten year, key significant findings emerged after controlling for continuity and within time correlation. Those children who exhibited more inattention and impulsivity in the fall had lower levels of school engagement by the end of the school year (B = −.27, β = −.19, p < .01), as well as greater teacher-child conflict (B = .56, β = .20, p < .01). Further, greater conflict between teacher and child in the fall was associated with a similar reduction in school engagement by spring (B = −.08, β = −.14, p < .05).

The pattern between inattention and impulsivity, and teacher-conflict, persisted from kindergarten to first grade: children who had higher levels of inattention and impulsivity at the end of kindergarten experienced more conflict with their first grade teachers (B = .70, β = .28, p < .001). These children also experienced reduced closeness with their first grade teachers (B = −.30, β = −.13, p < .05). School engagement at the end of kindergarten positively predicted teacher-child closeness (B = .25, β = .14, p < .05) and academic competence in first grade (B = .48, β = .29, p < .01).

Given that the pathways from inattention/impulsivity and conflict in fall were negatively related to school engagement in spring of kindergarten, which in turn was positively related to academic competence in the first grade, we conducted post-hoc analyses to examine the strength of the indirect effect of these variables across time using MODEL INDIRECT in Mplus. These supplemental analyses found a significant indirect effect (B = −.13, β = −.06, p < .01) from inattention/impulsivity to academic competence through school engagement. The indirect effect from conflict to academic competence was only marginally significant (B = −.04, β = −.04, p < .10).

Surprisingly, teacher-child conflict at the end of kindergarten was positively related to teacher-child closeness in first grade (B = .18, β = .20, p < .001), though these variables were not associated in the bivariate correlations. To probe this counterintuitive finding, we ran partial pairwise correlations between these variables, controlling for conflict in first grade. We examined how these correlations differ in children who experience high versus low conflict at the end of kindergarten, splitting the sample at the mean. The results showed that a positive correlation emerged for children who experienced high conflict at kindergarten spring (r = .25, p < .05), whereas the association was nonsignificant for children who experienced low conflict.

Discussion

Using nested path analytic models, this study examined transactional relations among teacher-child relationship quality, children’s behavior, and academic functioning. Importantly, this study employed independent measures across multiple informants and time points, and examined bidirectional pathways after accounting for longitudinal stability of each construct and within-time covariation between constructs.

After controlling for strong continuity across domains of children’s functioning and teacher-child relationship quality, children who exhibited inattention and impulsivity at school entry experienced an increase in conflict with teachers at the end of kindergarten and notably, this effect persisted into first grade. This relation was significant after accounting for the fact that inattention and impulsivity were strongly positively correlated with conflict at each time point. The strong effect of inattention and impulsive behaviors on teacher-child relationship quality began at the transition to elementary school, pointing to a need for strategies to help young children develop strong self-regulatory skills in preschool and earlier. Furthermore, inattention and impulsivity at the end of kindergarten predicted less closeness with first grade teachers, highlighting that these children may not receive the benefits of positive relationship quality due to their behavioral issues.

In contrast, conflict with teachers did not predict increases in inattention and impulsive behaviors across time. This ran counter to our original hypothesis that we would observe bidirectional transactions between teacher-child relationship quality and children’s behaviors, as has been found in other work (Arnold, et al., 1998; Doumen, et al., 2008; Leflot, et al., 2011). Instead, it appears that self-regulation skills have a unidirectional longitudinal effect on teacher-child conflict.

Although we did not find bidirectional transactions between self-regulation and teacher-child conflict, this study provides evidence that bidirectional transactions may work along different, yet interrelated, domains of children’s functioning. Specifically, initial levels of conflict with teachers predicted decreases in school engagement at the end of kindergarten after accounting for a strong negative correlation within each time point. Additionally, the theorized benefits of teacher-child closeness did not spillover to other domains of children’s functioning beyond the concurrent benefits at each time point. Prior evidence showing that closeness predicts prospective child functioning may be due to not controlling for the covariation between teacher-child closeness and conflict, which this study did account for. This study is one of the first to empirically examine transactional effects across multiple aspects of both teacher-child relationships and children’s functioning, thus, future research should continue to tease apart these relations.

The final model also resulted in a counterintuitive positive association between teacher-child conflict at the end of kindergarten and closeness reported at first grade spring. It appears that this result is being driven by children who experience high conflict at kindergarten spring. This indicates that some children who experience conflict with teachers in kindergarten may have an opportunity to establish new relationships with their teachers in first grade, over and above their concurrent conflict at each time point, highlighting a possible point of intervention. This is a noteworthy finding considering that both closeness and conflict exhibited strong stability across the three time points, particularly teacher-child conflict, consistent with work by Jerome and colleagues (2009).

In addition, inattention and impulsive behaviors were longitudinally associated with less school engagement at the end of kindergarten, over and above their strong, negative concurrent association. Thus, children who had more conflict with teachers or exhibited lower self-regulation experienced lower enthusiasm for school related activities, which subsequently undermined academic competence and closeness with teachers in first grade. This evidence is consistent with ideas put forth by Eisenberg et al. (2010) that school engagement mediates the relation between self-regulation and relationship quality with academic competence. Indeed, post-hoc analyses found a significant indirect effect of self-regulation on academic competence through school engagement, highlighting that future empirical studies should continue to test for mediation among these constructs.

Taken together, these findings suggest that challenges with self-regulation place young children at risk for negative relationships with teachers and lower academic functioning, particularly for boys. However, we do see some evidence of children getting a fresh start to develop new relationships with their later teachers, signifying the need to further examine characteristics of teachers who are able to competently manage and connect with children who display challenging behaviors.

Limitations and future directions

While this study provided a rigorous examination of children’s behavior and classroom processes to understand the link between self-regulation and academic competence, it is not without its limitations. First, this study could be strengthened by including measures of inattention and impulsivity through direct child assessment or observational methods to provide unbiased assessments of children’s self-regulatory behaviors. Further, direct observation of children’s school engagement or surveying children directly about their motivation and school liking would also triangulate the construct of school engagement with parent and teacher reports. However, it is notable that the current survey measure is comprised of both parent and teachers’ perspectives, strengthening the claims that can be made, particularly since new teachers were introduced in first grade. While some constructs have low correlation between parent and teacher informants in fall of kindergarten, potentially limiting the interpretation of the findings, it is important to note that orthogonal perspectives on behavior in the home and school contexts can correct for deficiencies in each informants’ data (Kraemer, et al., 2003).

We focused our research questions on measures of inattention and impulsivity because they are markers of low self-regulation and children who exhibit these behaviors tend to experience difficulty with learning and engagement, issues that may place them at risk for reduced academic achievement as they progress through school (Blair, 2002). However, these behaviors are multiply determined and are also related to externalizing problems. Due to model complexity, we were not able to control for concurrent aggressive-disruptive behaviors and isolate the unique effect of inattention and impulsivity; future studies should aim to do so.

This study could also be strengthened by including other measures of the classroom context. Analyses were limited by only using teacher-rated perspectives on the degree of closeness and conflict with any particular child. Classroom observations would provide an unbiased perspective of overall classroom climate yet may not capture the degree of closeness and conflict between individual teacher-child dyads. Incorporating children’s report on the relationship would provide another perspective, but questions remain whether five year olds can validly report on the relationship particularly if adult researchers interview them.

This study did not include any measure of teacher’s own social emotional competence or psychological attributes, qualities that may permit teachers to be better at reading children’s cues and supporting their social-emotional and cognitive needs (Downer, et al., 2010). Future research must incorporate both child and teacher characteristics to further illuminate how these interpersonal bonds develop in early schooling. Finally, while this study implemented multiple measures and multiple informants across time and examined transactional pathways in a stringent manner, ascertaining causality is not possible due to omitted variable bias, such as variables related to teacher’s own beliefs and competencies.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence of the key role that self-regulation plays in children’s early schooling. Findings highlight the need to provide teachers of young children with professional development to improve overall classroom climate and engage with dysregulated children in non-reactive ways as conflictual relationships can persist over time and impact these children’s academic trajectories. While it is easier to nurture closeness with children that do not exhibit problematic behaviors, supportive classroom environments may afford opportunities for all children, providing the maximum benefit for children experiencing higher degrees of behavior problems at school entry (Silver, et al., 2005). These children are precisely the ones who desperately need to have positive, supportive relationships with teachers to encourage their engagement with educational content. Interventions that promote emotionally supportive classrooms and learner-centered practices may allow these children to feel safe, reduce the risk for mental health problems (Boyce et al., 2012), and allow for academic risk taking necessary to foster stronger academic skills (Downer, et al., 2010). Further, supportive classrooms that increase the quality of experience for all children may have long term effects on individual earnings and educational outcomes (Chetty et al., 2011), highlighting the importance of early learning environments for societal savings. Finally, identifying strategies for promoting self-regulatory skills before children enter kindergarten is crucial in order to ensure that children start school on a positive academic trajectory.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant award R01 MH62320 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Preparation of this manuscript by Ximena A. Portilla was supported in part by the Institute of Education Sciences (IES), U.S. Department of Education, through Grant #R305B090016 to Stanford University and a research grant from the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR) to Jelena Obradović. The authors acknowledge the substantive contributions made by Juliet Stamperdahl and Nicole R. Bush in collecting and processing the data. The authors also thank the teachers, children, and families who participated and made this research possible. The findings, conclusions, and opinions here are those of the authors and do not represent views of the NIMH, IES, the U.S. Department of Education, or CIFAR.

Contributor Information

Ximena A. Portilla, Stanford Graduate School of Education

Parissa J. Ballard, University of California, San Francisco and University of California, Berkeley

Nancy E. Adler, University of California, San Francisco

W. Thomas Boyce, University of California, San Francisco.

Jelena Obradović, Stanford Graduate School of Education.

References

- Archambault I, Pagani L, Fitzpatrick C. Transactional associations between classroom engagement and relations with teachers from first through fourth grade. Learning and Instruction. 2013;23:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JM, Goldstein LH The MacArthur Working Group on Outcome Assessment. In: Manual for the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ 1.0) Kupfer David J., Chair, editor. University of Pittsburgh: MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Psychopathology and Development; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold DH, McWilliams L, Arnold EH. Teacher Discipline and Child Misbehavior in Day Care: Untangling Causality With Correlational Data. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:276–287. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JA. Contributions of teacher–child relationships to positive school adjustment during elementary school. Journal of School Psychology. 2006;44:211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Baker JA, Grant S, Morlock L. The teacher-student relationship as a developmental context for children with internalizing or externalizing behavior problems. School Psychology Quarterly. 2008;23:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:65–94. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Mash EJ, Terdal LG, editors. Assessment of childhood disorders. 3. New York: Guilford; 1998. pp. 71–129. [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, Ladd GW. The teacher-child relationship and children’s early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology. 1997;35:61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, Ladd GW. Children’s interpersonal behaviors and the teacher–child relationship. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:934–946. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of children’s functioning at school entry. American Psychologist. 2002;57:111. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Diamond A. Biological processes in prevention and intervention: The promotion of self-regulation as a means of preventing school failure. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20 doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Razza RP. Relating Effortful Control, Executive Function, and False Belief Understanding to Emerging Math and Literacy Ability in Kindergarten. Child Development. 2007;78:647–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Obradović J, Bush NR, Stamperdahl J, Kim YS, Adler N. Social stratification, classroom climate, and the behavioral adaptation of kindergarten children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:17168–17173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201730109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buyse E, Verschueren K, Doumen S. Preschoolers’ Attachment to Mother and Risk for Adjustment Problems in Kindergarten: Can Teachers Make a Difference? Social Development. 2011;20:33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R, Friedman JN, Hilger N, Saez E, Schanzenbach DW, Yagan D. How Does Your Kindergarten Classroom Affect Your Earnings? Evidence from Project STAR. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2011;126:1593–1660. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjr041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curby TW, Rimm-Kaufman SE, Ponitz CC. Teacher-Child Interactions and Children’s Achievement Trajectories Across Kindergarten and First Grade. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2009;101:912–925. [Google Scholar]

- Doumen S, Verschueren K, Buyse E, Germeijs V, Luyckx K, Soenens B. Reciprocal Relations Between Teacher–Child Conflict and Aggressive Behavior in Kindergarten: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:588– 599. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downer JT, Sabol TJ, Hamre B. Teacher–Child Interactions in the Classroom: Toward a Theory of Within- and Cross-Domain Links to Children’s Developmental Outcomes. Early Education & Development. 2010;21:699– 723. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan G, Dowsett C, Claessens A, Magnuson K, Huston A, Klebanov P, et al. School readiness and later achievement. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1428–1446. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Eggum ND. Self-Regulation and School Readiness. Early Education & Development. 2010;21:681– 698. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2010.497451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH. School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence. Review of Educational Research. 2004;74:59–109. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano PA, Reavis RD, Keane SP, Calkins SD. The role of emotion regulation in children’s early academic success. Journal of School Psychology. 2007;45:3–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC. Early Teacher–Child Relationships and the Trajectory of Children’s School Outcomes through Eighth Grade. Child Development. 2001;72:625–638. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GD, Dweck CS. Achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: Their relation and their role in adaptive motivation. Motivation and Emotion. 1992;16:231–247. [Google Scholar]

- Hu Lt, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Luo W, Kwok OM, Loyd LK. Teacher-student support, effortful engagement, and achievement: A 3-year longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2008;100:1–14. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.100.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerome EM, Hamre BK, Pianta RC. Teacher–Child Relationships from Kindergarten to Sixth Grade: Early Childhood Predictors of Teacher-perceived Conflict and Closeness. Social Development. 2009;18:915–945. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Measelle JR, Ablow JC, Essex MJ, Boyce WT, Kupfer DJ. A New Approach to Integrating Data From Multiple Informants in Psychiatric Assessment and Research: Mixing and Matching Contexts and Perspectives. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1566–1577. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Buhs ES, Seid M. Children’s initial sentiments about kindergarten: Is school liking an antecedent of early classroom participation and achievement? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2000;46:255–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Dinella LM. Continuity and change in early school engagement: Predictive of children’s achievement trajectories from first to eighth grade? Journal of Educational Psychology. 2009;101:190–206. doi: 10.1037/a0013153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leflot G, van Lier PAC, Verschueren K, Onghena P, Colpin H. Transactional Associations Among Teacher Support, Peer Social Preference, and Child Externalizing Behavior: A Four-Wave Longitudinal Study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40:87–99. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.533409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew J, Chen Q, Hughes JN. Child effortful control, teacher–student relationships, and achievement in academically at-risk children: Additive and interactive effects. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2010;25:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Hau KT, Wen Z. In Search of Golden Rules: Comment on Hypothesis-Testing Approaches to Setting Cutoff Values for Fit Indexes and Dangers in Overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) Findings. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2004;11:320–341. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland MM, Cameron CE, Connor CM, Farris CL, Jewkes AM, Morrison FJ. Links Between Behavioral Regulation and Preschoolers’ Literacy, Vocabulary, and Math Skills. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:947–959. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez JL, McDermott P, Fantuzzo J. Identifying and promoting social competence with African American preschool children: Developmental and contextual considerations. Psychology in the Schools. 2002;39:111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Miller SA. Parents’ Attributions for Their Children’s Behavior. Child Development. 1995;66:1557–1584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 5. Los Angeles: Author; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Myers SS, Morris AS. Examining Associations Between Effortful Control and Teacher–Child Relationships in Relation to Head Start Children’s Socioemotional Adjustment. Early Education & Development. 2009;20:756–774. doi: 10.1080/10409280802571244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers SS, Pianta RC. Developmental Commentary: Individual and Contextual Influences on Student–Teacher Relationships and Children’s Early Problem Behaviors. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:600–608. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor E, McCartney K. Examining Teacher–Child Relationships and Achievement as Part of an Ecological Model of Development. American Educational Research Journal. 2007;44:340–369. [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Sameroff AJ, Kerr DCR, Lopez NL, Wellman HM. Developmental foundations of externalizing problems in young children: The role of effortful control. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:25–45. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry KE, Donohue KM, Weinstein RS. Teaching practices and the promotion of achievement and adjustment in first grade. Journal of School Psychology. 2007;45:269–292. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC. Enhancing relationships between children and teachers. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 1999. Assessing child-teacher relationships; pp. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Belsky J, Vandergrift N, Houts R, Morrison FJ. Classroom Effects on Children’s Achievement Trajectories in Elementary School. American Educational Research Journal. 2008;45:365–397. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Steinberg MS, Rollins KB. The first two years of school: Teacher-child relationships and deflections in children’s classroom adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Rimm-Kaufman SE, Pianta RC. An Ecological Perspective on the Transition to Kindergarten: A Theoretical Framework to Guide Empirical Research. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2000;21:491–511. [Google Scholar]

- Roorda DL, Koomen HMY, Spilt JL, Oort FJ. The Influence of Affective Teacher–Student Relationships on Students’ School Engagement and Achievement. Review of Educational Research. 2011;81:493–529. [Google Scholar]

- Rudasill KM, Rimm-Kaufman SE. Teacher–child relationship quality: The roles of child temperament and teacher–child interactions. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2009;24:107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, MacKenzie MJ. Research strategies for capturing transactional models of development: The limits of the possible. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:613–640. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A. Scaled and Adjusted Restricted Tests in Multi Sample Analysis of Moment Structures. UPF Economics & Business Working Paper, No. 395 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. Vol. 72. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva KM, Spinrad TL, Eisenberg N, Sulik MJ, Valiente C, Huerta S, et al. Relations of Children’s Effortful Control and Teacher–Child Relationship Quality to School Attitudes in a Low-Income Sample. Early Education & Development. 2011;22:434–460. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2011.578046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver RB, Measelle JR, Armstrong JM, Essex MJ. Trajectories of classroom externalizing behavior: Contributions of child characteristics, family characteristics, and the teacher–child relationship during the school transition. Journal of School Psychology. 2005;43:39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Spilt JL, Hughes JN, Wu JY, Kwok OM. Dynamics of Teacher–Student Relationships: Stability and Change Across Elementary School and the Influence on Children’s Academic Success. Child Development. 2012;83:1180–1195. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01761.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipek D, Miles S. Effects of aggression on achievement: Does conflict with the teacher make it worse? Child Development. 2008;79:1721–1735. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente C, Lemery-Chalfant K, Swanson J. Prediction of kindergartners’ academic achievement from their effortful control and emotionality: Evidence for direct and moderated relations. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2010;102:550–560. [Google Scholar]

- Valiente C, Swanson J, Lemery-Chalfant K. Kindergartners’ Temperament, Classroom Engagement, and Student–teacher Relationship: Moderation by Effortful Control. Social Development. 2012;21:558–576. [Google Scholar]

- Walker S, Berthelsen DC, Irving KA. Temperament and peer acceptance in early childhood: Sex and social status differences. Child Study Journal. 2001;31:177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR. Social-motivational processes and interpersonal relationships: Implications for understanding motivation at school. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1999;91:76–97. [Google Scholar]