Abstract

Background

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is a serious, common condition associated with frequent hospitalisation. Several different disease management interventions (clinical service organisation interventions) for patients with CHF have been proposed.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of disease management interventions for patients with CHF.

Search methods

We searched: Cochrane CENTRAL Register of Controlled Trials (to June 2003); MEDLINE (January 1966 to July 2003); EMBASE (January 1980 to July 2003); CINAHL (January 1982 to July 2003); AMED (January 1985 to July 2003); Science Citation Index Expanded (searched January 1981 to March 2001); SIGLE (January 1980 to July 2003); DARE (July 2003); National Research Register (July 2003); NHS Economic Evaluations Database (March 2001); reference lists of articles and asked experts in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing disease management interventions specifically directed at patients with CHF to usual care.

Data collection and analysis

At least two reviewers independently extracted data information and assessed study quality. Study authors were contacted for further information where necessary.

Main results

Sixteen trials involving 1,627 people were included. We classified the interventions into three models: multidisciplinary interventions (a holistic approach bridging the gap between hospital admission and discharge home delivered by a team); case management interventions (intense monitoring of patients following discharge often involving telephone follow up and home visits); and clinic interventions (follow up in a CHF clinic). There was considerable overlap within these categories, however the components, intensity and duration of the interventions varied.

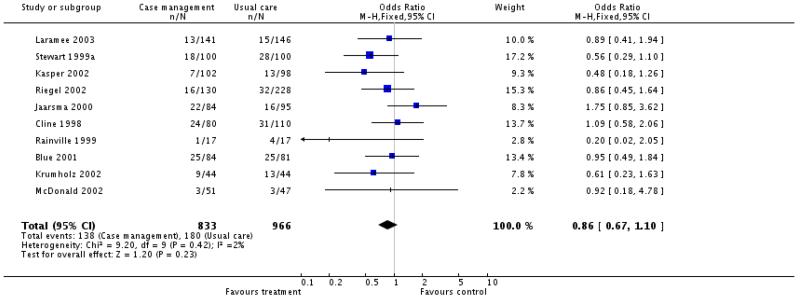

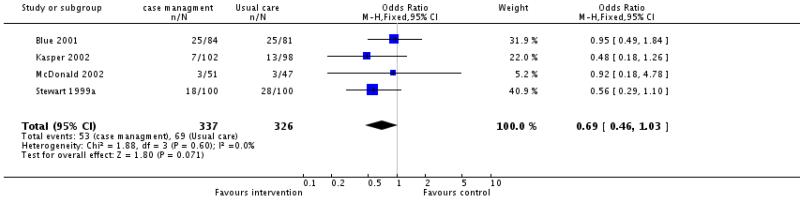

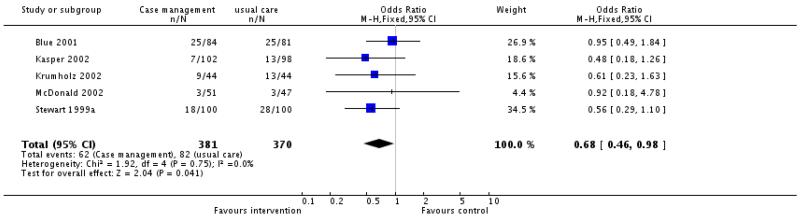

Case management interventions tended to be associated with reduced all cause mortality but these findings were not statistically significant (odds ratio 0.86, 95% confidence interval 0.67 to 1.10, P = 0.23), although the evidence was stronger when analysis was limited to the better quality studies (odds ratio 0.68, 95% confidence interval 0.46 to 0.98, P = 0.04). There was weak evidence that case management interventions may be associated with a reduction in admissions for heart failure. It is unclear what the effective components of the case management interventions are.

The single RCT of a multidisciplinary intervention showed reduced heart-failure related re-admissions in the short term. At present there is little available evidence to support clinic based interventions.

Authors’ conclusions

The data from this review are insufficient for forming recommendations. Further research should include adequately powered, multicentre studies. Future studies should also investigate the effect of interventions on patients’ and carers’ quality of life, their satisfaction with the interventions and cost effectiveness.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Case Management [*organization & administration], Chronic Disease, Heart Failure [*therapy], Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

MeSH check words: Humans

BACKGROUND

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is a serious and increasingly common condition (Cleland 1999; Cowie 1997; Eriksson 1995) with a crude prevalence of 3 to 20 per 1000 in the general population (Cowie 1999). Both the incidence and prevalence of CHF increase with age, from around one per cent of those aged 50-59 years to 10 per cent of those aged 80-89 years (Kannel 1991) and most patients with heart failure are elderly. In Scotland the mean age at first hospital admission for CHF is 74 years (Cleland 1999) and in the United States half of all patients over 65 years admitted with CHF are over 80 years old (Havranek 2002). The condition carries a substantial risk of death - in recent community studies between a quarter and a third of patients were dead one year after the onset of heart failure (Cowie 2000; Levy 2002), and around two thirds of men and half of women were dead after five years (Levy 2002). In a study of Scottish data the median survival time after a first hospital admission with CHF was sixteen months and the five year survival rate was 25% - worse than that for all common malignancies except lung and ovarian cancer (Stewart 2001b). A Canadian population based study of survival after a first hospital admission for heart failure reported a case fatality rate of 31% at one year follow up (Jong 2002). In addition to the risk of death the condition has a profound impact on patients’ quality of life (Stewart 1989).

Hospital admissions for heart failure have steadily increased and heart failure is now one of the most common reasons for admission in older people (AHA 2004; Cleland 1999; McMurray 1993). It has been estimated that in 2000 1.9% of the total budget of the National Health Service (£905 million) was spent on patients with heart failure and most of this cost was incurred by hospital admissions (Stewart 2002a). A community study from England found 55% of patients in primary care being treated with loop diuretics and with a clinical diagnosis CHF had an acute admission to hospital with heart failure (Clarke 1994). Early hospital readmission in patients with heart failure is extremely common. In Connecticut, USA, between 1991 and 1994, 44% of all patients admitted for congestive heart failure were re-admitted (all causes) within six months (Krumholz 1997). In the recent EuroHeart Failure survey, which included 24 countries, 24% of patients admitted with confirmed or suspected heart failure were readmitted to hospital within 12 weeks - heart failure was the principal cause of readmission (20% of readmissions) and contributed to a further 16% of readmissions (Cleland 2003). Studies suggest that many early re-admissions for heart failure are preventable (Feenstra 1998; Michalsen 1998; Vinson 1990).

Drug therapy is the mainstay of treatment for CHF, although invasive procedures are indicted for some patients, and patients are usually managed with a combination of medications and lifestyle advice (NICE 2003). The management of patients with heart failure has been described as evolving from the traditional model with its emphasis on crisis intervention towards more proactive, preventative disease management models. These emerging care models offer “aggressive care” in hospital, home or clinic (Riegel 2001). In view of the importance of heart failure both to patients and to health services as a whole, a systematic review of specific interventions aimed at reducing hospital re-admissions in heart failure is needed to help inform health care professionals in the provision of more effective care for these patients.

OBJECTIVES

Primary objective

To assess systematically the effects of different clinical service interventions, which are not primarily educational in focus, in preventing death and/or hospital re-admission in patients who have previously been admitted to secondary care with a diagnosis of heart failure. (Wherever possible examining event free survival: that is survival without hospital re-admission).

Secondary objective

To assess the effects of the different clinical service interventions in terms of other outcomes that may have been reported such as hospital bed days, health related quality of life and cost.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Only randomised controlled trials were included in the analyses.

Types of participants

Adults who had at least one admission to secondary care with a diagnosis of heart failure were the focus of this review. Studies dealing principally with patients with cardiac disorders other than heart failure, or with heart failure arising from congenital heart disease and/or valvular heart disease, were excluded.

Types of interventions

Clinical service interventions were defined as inpatient, outpatient or community based interventions or packages of care, excluding the simple prescription or administration of a pharmaceutical agent(s), which are applied to patients with heart failure and their relatives or carers. These interventions included enhanced or novel service provision for patients with heart failure. Interventions that were primarily educational in focus were not included in this review. Interventions that included an educational component as part of a broader programme of enhanced service provision were included in this review. These interventions were compared with ‘usual care’ for this patient group.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

deaths (all cause and heart failure related);

re-admission to secondary care;

total number of re-admissions and number of unplanned re-admissions;

total hospital bed days (all cause and heart failure related);

length of time between index hospital discharge and unplanned re-admission;

event free survival (with an event defined as death or hospital re-admission).

We intended to examine re-admissions at fixed time intervals from discharge if possible.

Secondary outcomes

health related quality of life;

cost analyses.

Search methods for identification of studies

The search strategy was developed before the Heart Cochrane Review Group search strategy was published and our search strategy was wider since we originally considered including non-randomised, prospective studies with concurrent control groups in secondary analyses. (This idea was abandoned because we had difficulty in identifying studies which met our quality criteria and the results of the very few non-randomised studies we considered including did not influence the conclusions of this review). The searches for the individual databases are shown in the additional studies table (Table 1). No language restrictions were applied.

Our search consisted of the following steps:

-

(1)The following electronic databases were searched:

- Cochrane CENTAL Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), The Cochrane Library, Issue 2 2003;

- MEDLINE January 1966 to July 2003;

- EMBASE January 1980 to July 2003;

- CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) January 1982 to July 2003;

- AMED (Allied and Alternative Medicine Database, covers occupational therapy, physiotherapy and complementary medicine) January 1985 to July 2003;

- Science Citation Index Expanded searched January 1981 to March 2001 (forward and backwards search, see below);

- SIGLE Jan 1980 to July 2003;

- Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) to July 2003;

- National Research Register to July 2003;

- NHS Economic Evaluations Database to March 2001;

- Cardio-Vascular Disease (CVD) Trials Registry at McMaster University (entire database searched on 7/2/2001);

- Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP) Library Catalogue to June 2001.

-

(2)

Citation tracking: reference lists of retrieved articles and published reviews on the topic were retrieved. In addition to a backward search of the Science Citation Index using key words (see below) we also conducted a forward search of articles using the five earliest eligible studies identified from electronic database searching.

-

(3)

Personal communication with the principal investigators of the identified RCTs and with national and international experts in the field.

Data collection and analysis

-

(1)

CENTRAL was searched by the Cochrane Heart Group. All other electronic searches were conducted by two members of the group working independently. A librarian with extensive expertise in electronic databases provided advice on searching;

-

(2)

Group training was conducted on the first 100 references retrieved from searches of two different databases to ensure that the group had a consistent approach to assessing titles and abstracts;

-

(3)

The title and abstract of each reference retrieved was assessed by two members working independently. Titles and abstracts of non-English language papers were translated into English;

-

(4)

The full texts of all potentially eligible papers were obtained and assessed for eligibility by two members of the group working independently. Non English language papers which appeared to be eligible for inclusion on the basis of the translation of title and abstract were fully translated in to English;

-

(5)

Any disagreements about eligibility were resolved by discussion between at least three members of the group;

-

(6)

A data abstraction form was developed and the group worked together on several papers to ensure that members had a consistent approach to data abstraction;

-

(7)

All eligible papers were formally abstracted by at least two members of the group working independently and using the data collection form. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion with another member of the group;

-

(8)

Where we were unclear about issues arising from their published papers we attempted to contact the authors for clarification.

Assessing the methodological quality and external validity of the trials

The quality of the studies was assessed in terms of allocation concealment and, not specified in our protocol but added in order to enhance our understand of the studies, we also considered the criteria for quality assessment of RCTs developed by Verhagen (Verhagen 1998). (We excluded two items “was the patient blinded?/masked” and “was the care provider masked?”, since these make less sense in the context of the type of interventions under study).

The quality items considered were:

-

(1)Treatment allocation

-

(a)Was a method of randomisation performed?

-

(b)Was the treatment allocation concealed?

-

(a)

-

(2)

Were the groups similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators?

-

(3)

Were the eligibility criteria specified?

-

(4)

Was the outcome assessor masked?

-

(5)

Were point estimates and measures of variability presented for the primary outcome measures?

-

(6)

Did the analysis include an intention to treat analysis?

We also commented on the risk of attrition bias. Statistical power and generalisability refer to the external validity of studies and we also commented on these. All included studies were examined by two medical statisticians working independently.

Categorising the interventions

Riegel has proposed three types of heart failure disease management models and, although we did not mention any categorisation in our protocol, we have used her typology to group the different interventions for synthesis (Riegel 2001). The models are described as follows:

Multidisciplinary models

Multidisciplinary models offer a holistic approach to the individuals’ medical, psychosocial, behavioural and financial circumstances and typically involve several different professions working in collaboration. “The gap between hospitalisation, other health care delivery systems (e.g. skilled nursing facilities, hospice) and home is bridged by a team of individuals knowledgeable about heart failure and committed to patient care.”

Case management models

Case management models consist of intense monitoring of the patients following discharge from hospital, this is usually done by a nurse and typically involves home visits and/or telephone calls.

Clinic models

Clinic models involve outpatient clinics for heart failure, they are usually run by cardiologists with a special interest in heart failure or by specialist nurses using agreed protocols to manage medication. Results of the individual studies were initially combined in a narrative review, weighted according to the methodological quality of each. Where possible and appropriate, the trial results were combined statistically using meta-analytic methods.

Data analysis

Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for dichotomous variables, such as death. In the absence of significant heterogeneity, using the Cochrane Q statistic (p>0.1), summary ORs and 95% CIs were calculated using a fixed-effects meta-analysis.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

The electronic searches retrieved a number of studies examining the effect of interventions directed at populations of older people and not exclusively aimed at patients with heart failure. We have excluded these studies from this review (See Excluded Studies Table). Inclusion of studies examining the effect of these sort of “generic” interventions would have necessitated a different search strategy.

Our search strategy identified 28,046 papers including very many duplicates and a number of reviews and guidelines. We excluded 27,840 references by removing duplicates and after screening titles and abstracts. Two hundred and six papers, including major review articles and guidelines, were retrieved. Examination of the full papers led to the exclusion of a further 185 papers. Excluded studies which relate to the area reviewed are described in the Excluded Studies Table.

We identified 21 publications for inclusion in the review; these described 16 individual RCT studies and 15 different interventions. Two of the RCTs identified were feasibility or pilot studies (Ekman 1998; Rich 1993), one (Rich 1993) informed a much larger study (Rich 1995) which is also included in the review. Control patients received unrestricted ‘usual’ or ‘routine’ care in all the studies except one where both control and intervention patients received a programme of ‘optimised’ medical care during the index hospitalisation (McDonald 2002).

All the included studies were conducted at a single centre with the exception of one which involved two centres (Kasper 2002). All the studies were led by professionals from secondary or tertiary care. As determined by scrutiny of the published accounts, none of the 15 different interventions were delivered in exactly the same way by the same type of personnel, although some were very similar and all the interventions had overlapping content (see Table 2) The interventions varied in site, intensity and duration (see Table 2, and Table of characteristics of included studies). Length of follow up ranged from 12 weeks to one year.

Content of the interventions as described in the published reports

Telephone follow up

Ten interventions included scheduled, pro active telephone follow up of patients at home and a two further studies involved a single telephone call following hospital discharge .

Education

Education aimed at patients, and in some cases carers, appears to have been a major component in at least twelve of the interventions. The education typically covered the diagnosis, symptoms and treatment of heart failure and when to seek expert help.

Self management

Many of the interventions actively sought to promote better patient self management and patients were sometimes given heart failure diaries or notebooks to aid self management.

Weight monitoring

Daily or regular weight monitoring, or the importance of weight monitoring, was mentioned in nine of the interventions, patients in these studies were often given charts or diaries in which to log their weights and in two cases some patients were supplied with weigh scales.

Sodium restriction and/or dietary advice

This was mentioned in seven interventions and ranged from a dietician’s visit and an individualised 1.5-2.0 g per day sodium diet to a list of dietary recommendations.

Exercise recommendations

These were specifically mentioned in six of the studies.

Medication review

Only two of the interventions specifically mentioned a review of the patients’ medications, in one this was conducted by a geriatric cardiologist and in the other by a hospital pharmacist.

Social support and psychological support

Social workers assessed patients’ needs in two interventions, outpatient support groups featured in one intervention and one study stated that the heart failure specialist nurse gave patients psychological support.

Table 2 lists the components of the interventions as described in the published papers against the studies.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All the studies differed in their inclusion and exclusion criteria. The age range for patients included in the studies varied from over 18 years (Jaarsma 2000; McDonald 2002) to over 70 years (Rich 1995); one study had an upper age limit of 84 years (Cline 1998). All the studies identified patients during an index hospital admission for CHF but several reports did not specify the criteria used for identifying CHF. One study required patients to have had at least one admission for acute heart failure prior to the index admission (Stewart 1999a) and three other interventions were targeted at patients the researchers considered to be at high risk for re-admission (Kasper 2002; Laramee 2003; Rich 1995). One study required that patients would be discharged home with nursing care (Harrison 2002). Only one study specifically excluded patients with diastolic heart failure (Blue 2001).

Five of the studies mentioned excluding patients with valvular heart disease requiring surgery (Doughty 2002; Jaarsma 2000; Kasper 2002; McDonald 2002; Stewart 1999a). Several studies specifically excluded CHF associated with acute myocardial infarction (Blue 2001; Ekman 1998; Kasper 2002; McDonald 2002) although CHF precipitated by acute MI was one of four independent risk factors in the inclusion criteria in one study (Rich 1995). The presence of serious co-morbidity or other terminal illness was a common exclusion criterion (Blue 2001; Cline 1998; Ekman 1998; Harrison 2002; Jaarsma 2000; Krumholz 2002; Laramee 2003; McDonald 2002; Rainville 1999; Riegel 2002) and most of the studies excluded patients discharged to long term care facilities such as nursing homes (Blue 2001; Ekman 1998; Harrison 2002, Jaarsma 2000; Kasper 2002; Krumholz 2002; Larame 2003; McDonald 2002; Rainville 1999; Rich 1995; Riegel 2002).

The patients enrolled in the studies

The mean or median age of the patients involved in the interventions lay between 70 and 80 years. However they were younger in Kasper’s study (median age 63.5 years, range 25-88) and the participants in Capomolla’s study were particularly young compared to the other studies (mean age 56 years, SD 10). The proportion of male study subjects varied from 86% (Capomolla 2002) to 23% (Rich 1995). The proportion of patients from different ethnic groups was rarely stated. Where it was reported this ranged from 45% white (Rich 1995) to 77% ‘European’ (Doughty 2002).

Categorising the interventions

The types of personnel involved in the interventions differed but specialist nurses were common to all studies, although the level of their involvement varied. We used Riegel’s classification (Riegel 2002, see Methods) to group the interventions based on the content and nature of the interventions as they were described in the papers. In practice there appears to be considerable overlap between these disease management models and it was not always easy to classify them, Table 2 summarises some of the similarities and differences between the interventions. One intervention involved a day hospital heart failure management programme (Capomolla 2002) and was difficult to categorise. We considered that the remaining interventions fell predominantly into the following groups:

One reflected a multidisciplinary approach (Rich 1993; Rich 1995).

Eleven RCTs appeared to involve variations on the case management approach (Cline 1998; Rainville 1999; Stewart 1999a; Jaarsma 2000; Blue 2001; Harrison 2002; Kasper 2002; Krumholz 2002; McDonald 2002; Riegel 2002; Laramee 2003). Two of these interventions were largely educational (Jaarsma 2000; Krumholz 2002), and three involved a combination of case management with follow up in a heart failure clinic (Cline 1998; Kasper 2002; McDonald 2002).

Two represented clinic models (Ekman 1998; Doughty 2002).

Risk of bias in included studies

We have noted in the Table results of included studies (Table 3) where there were concerns about the suitability or clarity of the particular statistical tests reported in the papers. Allocation concealment had been practiced in seven of the 16 studies (Blue 2001; Ekman 1998; Harrison 2002; Kasper 2002; McDonald 2002; Rich 1995; Stewart 1999a) and the outcome assessor was masked in five (Blue 2001; Harrison 2002; Kasper 2002; Krumholz 2002; Stewart 1999a) (see Table characteristics of included studies). Results of methodological quality assessment of the included RCTs using the Delphi criteria are shown in the Delphi Table (Table 4). Only one study met all the Delphi criteria we used (Stewart 1999a). Eight other studies (Blue 2001; Ekman 1998; Harrison 2002; Kasper 2002; Krumholz 2002; McDonald 2002; Rich 1993; Rich 1995) appeared to be of at least moderate quality using the Delphi criteria, although in half of these the outcome assessor was not masked. Three studies appeared to be of lower quality using these criteria (Jaarsma 2000; Laramee 2003; Rainville 1999) and there was insufficient information to assess the quality of the remaining four studies (Capomolla 2002; Cline 1998; Doughty 2002; Riegel 2002).

Statistical consideration of the studies

Even excluding the pilot and feasibility studies, most of the studies in the review had fairly small sample sizes. A power calculation shows that if the proportion of patients who are event free in the intervention arm is 0.3 and 0.5 in the control arm then 134 patients are needed in both arms to give 80% power of detecting the difference with the probability of a type 1 error of 0.05. Few of the included studies had samples of this size. There are a few cases where significant results are reported in very small studies (e.g. (Rainville) 17 in each arm; (Krumholz) 48 in each arm; (McDonald) 51 and 47 in the two arms). Here the studies are not underpowered because a significant result has been found, but when interpreting and attempting to synthesise these results we must be aware of the possibility of publication bias. Comments on statistical considerations for the individual studies are given in Table 3.

Effects of interventions

The Table of results of included studies (Table 3) documents results of primary and secondary endpoints and includes a comment on the statistical analyses used in each individual paper.

Synthesis of the findings from the included studies

Because of our concerns about the analysis of one study (Riegel 2001, see Table 3) we have excluded this study from the synthesis of all the outcomes except mortality. We have presented the results of Capomolla’s study separately because of the unique characteristics of both the intervention and the patients it was directed at (see Characteristics of Included Studies Table).

Mortality

All cause deaths

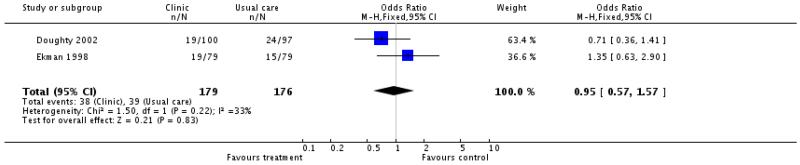

Thirteen of the 16 studies provided information on all cause mortality, none reported a significant difference in all cause mortality between intervention and control patients. Meta-analysis of the 10 case management interventions with data on mortality revealed a non-significant tendency for these interventions to be associated with reduced mortality, odds ratio 0.86 (95% confidence interval 0.67 to 1.10, P = 0.23) (Figure 01.01), however it must be emphasised that these interventions differed in content and that duration of the intervention and the length of follow up varied (see Table 5 and characteristics of included studies table). (We have ordered the studies by length of follow up in Figure 01.0, We rejected the idea of conducting separate analyses by duration of follow up because there would be very few studies in each group). When the meta-analysis was limited to the four case management studies with allocation concealment the odds ratio approached significance, odds ratio 0.69 (95% confidence interval 0.46 to 1.03, P = 0.07) (Figure 01.02) and when it was limited to those studies considered to be of at least moderate quality using the Delphi criteria there was a significant tendency for improved survival with the intervention, odds ratio 0.68 (95% confidence interval 0.46 to 0.98, P = 0.04) (Figure 01.03). Again it must be noted that the content and duration of these interventions, and the length of follow up varied. Our meta-analysis of the clinic intervention RCTs must be interpreted with extreme caution since there were only two studies and they had different follow up periods; no evidence of an effect on mortality was seen, odds ratio 0.95 (95% confidence interval 0.57 to 1.57, P = 0.83) (Figure 02.01). The single RCT of a multidisciplinary intervention found a greater proportion of deaths in the intervention group compared to the control group across the follow up period but the difference was not significant (Table 3).

Heart failure related mortality

Only one study reported on heart failure or cardiac related mortality: Capomolla’s study (Capomolla 2002) of a day hospital based heart failure management programme reported a highly significant reduction in cardiac related deaths in the intervention group. However total deaths were not reported, it is not clear how cardiac related deaths were identified, and the study population appears to be highly selected so the generalisability of this finding is unclear.

Event free survival

Information on event free survival (survival without all cause re-admission or death) was provided for nine of the 16 included RCTs. Event free survival was reported in a variety of ways. The most common way was as comparisons of proportions of patients who had experienced death or re-admission at different time points, sometimes survival curves and log-rank tests, hazard ratios or Cox’s proportional hazards regression analyses were presented. It was not feasible to conduct a statistical meta-analysis on these results.

Seven case management interventions reported event free survival, usually this meant the avoidance of both death from any cause and hospital readmission for heart failure. At three months follow up one moderate quality study reported a significant difference favouring case management (4 vs. 12, P = 0.04, Fisher’s exact test) (McDonald 2002). A study of unclear quality which considered death or readmission (probably all cause readmission) at three months reported no significant differences (Cline 1998). At six months follow up one high quality case management study (Stewart 1999a) found more patients survived without an unplanned readmission to hospital amongst the intervention group than the control group 51% vs. 38%, P = 0.04, (95% confidence intervals not given) whilst one moderate quality study reported no difference (P = 0.12 log-rank test) (Kasper 2002). At 12 months follow up two moderate quality studies reported hazard ratios for event free survival which favoured the case management intervention; Blue 2001, 31 vs. 43, hazard ratio 0.61 (95% confidence interval 0.38 to 0.96, P = 0.03); (Krumholz 2002, hazard ratio 0.5 (95% confidence interval 0.29 to 0.09, P = 0.02) as did another very small study judged to be of lower quality (P < 0.01 log rank test) (Rainville 1999). Cline reported no significant differences on event free survival at 12 months (56 patients (70%) vs. 79 (72%), Cline 1998).

Neither of the two studies of clinic interventions reported a significant difference in event free survival between intervention and control groups (Ekman 1998, moderate quality, 30 patients (30%) vs. 25 (32%) surviving at six months; Doughty 2002, unknown quality, event free survival at 12 months P = 0.33 kaplan meier survival curves). Both these studies may have lacked sufficient power Doughty’s was terminated early and Ekman’s was a smaller feasibility study (see Table 3). The single, large RCT of a multidisciplinary intervention found no significant difference in event free survival at three months between intervention and control groups (Rich 1995), this was the study’s primary outcome and the study was adequately powered.

Only one paper (McDonald 2002) reported on survival without heart failure related hospital admission. This found a significant reduction in the case managed group but the outcome assessors were not masked and it is not clear how heart failure related re-admissions were defined or identified.

Re-admissions to secondary care

Unplanned re-admissions

There is evidence from one high quality trial (Stewart 1999a) that case management may reduce the frequency of unplanned re-admissions (for all causes) at six months (mean re-admissions per month 0.14 (95% confidence interval 0.10 to 0.18); vs. 0.34 (95% confidence interval 0.19-0.49, P = 0.03, test not clear). This effect appears to have been sustained to 18 months; group mean re-admissions per month 0.15 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.19); vs. 0.37 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.55, P = 0.053). However it is not clear how unplanned re-admissions were defined or identified although outcome assessors were masked. None of the other included case management studies reported the frequency of unplanned re-admissions.

All cause re-admissions

Eleven of the 16 included studies provided some useable information on all cause hospital re-admissions. Information on all cause re-admissions was presented in a variety of ways by the individual studies (see Table 3) and it was not possible to perform any meaningful meta-analyses on these results. Seven of the eleven case management studies reported on all cause readmissions in some way at three (Harrison 2002; Laramee 2003), nine (Jaarsma 2000) and 12 months follow up (Blue 2001; Cline 1998; Krumholz 2002; Rainville 1999). Blue (Blue 2001) reported no difference in the number of patients admitted to hospital for all causes between the intervention and control groups but did report a reduction in the average number of admissions per month in the intervention group; hazard ratio 0.71 (95% confidence intervals 0.54 to 0.94, P = 0.02). In all but one of the other case management studies there appear to have been fewer readmissions in the case managed patients but the differences were not statistically significant in any of the studies.

Only one of the clinic studies reported on all cause readmissions: in Cline’s study there were fewer readmissions in the clinic managed group compared to the controls (re-admissions per patient per year 1.37 vs. 1.84, method of calculation not given, rate difference = 0.47 per patient per year (95% confidence interval 0.16 to 0.78) (Cline 1998). At three months follow up Rich found a significant reduction in the total number of all cause re-admissions in the multidisciplinary management group; total number of readmissions in 90 days 53 vs. 90, P = 0.02 Wilcoxon rank-sum test, patients with at least one re-admission in 90 days 41 (28.9%) vs. 59 (42.1%), absolute difference 13.2% (95% confidence interval 2.1 to 24.3, P = 0.03) but no significant difference in readmission rates after nine months (Rich 1995).

Capomolla (Capomolla 2002) noted a highly significant reduction in hospital readmissions in his intervention group (total number of hospital readmissions at mean 12 (SD 3) months follow up: 13 vs. 78, P<0.00001) but the generalisability and quality of this study are very unclear. It is also not clear if these are all cause readmissions or readmissions for haemodynamic instability.

Heart failure related re-admissions

Nine studies attempted to distinguish between heart failure, or cardiac, related events and events which were not related to heart failure or a cardiac illness. Such distinctions were necessary to determine the primary outcomes of some studies. Despite this only two RCTs provided any details in their publications on how they adjudicated whether events were heart failure related or not (Blue 2001; Kasper 2002) and none of the studies provided any information on the validation of these categorisations.

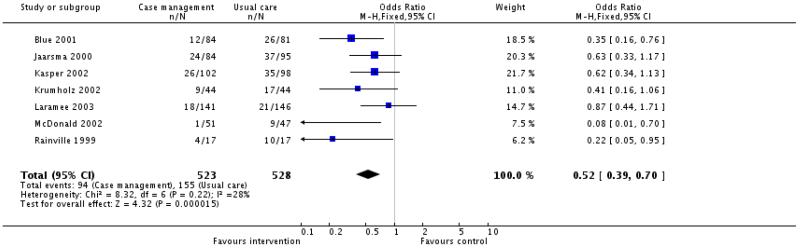

Only seven of the eleven case management studies reported the number of patients experiencing at least one hospital readmission for heart failure during follow up. Meta-analysis of these results suggests that case management may be associated with a reduction in heat failure readmissions during follow up; odds ratio 0.52 (95% confidence interval 0.39 to 0.70) (Figure 01.04). However it must be emphasised that these studies differed in their components, their duration, the length of follow up and their quality. Moreover the outcome assessor was masked in only three of these studies.

One clinic intervention study reported no differences in the number of hospital readmissions for heart failure or the number of patients experiencing a readmission at 12 months (Cline 1998). Rich (Rich 1995) reported significantly fewer heart failure related re-admissions in the multidisciplinary care group compared to the control group at three months but not at nine months.

Days spent in hospital during re-admissions

Eight studies (including Riegel 2002) reported on days spent in hospital during readmission. Stewart’s study of case management explored unplanned days in hospital and found a reduction in the intervention group at both at six months and 18 months; results at six months: 460 days vs. 1174, event rates per month 0.9 (95% confidence interval 0.6 to 1.2), vs. 2.9 (95% confidence interval 1.9 to 3.9, P = 0.01). However at six months there were similar proportions of unplanned re-admissions associated with a primary diagnosis of heart failure in each group (34 (50%) intervention vs. 58 (49%) controls) (Stewart 1999a). None of the other four case management studies reporting this outcome found a difference in all cause hospital bed days during follow up. Of the two moderate quality studies that examined days spent in hospital for readmissions associated with heart failure at 12 months, Blue 2001 reported significantly fewer bed days in the case managed groups (mean days spent in hospital with worsening HF 3.43, SD 12.2 vs. 7.46, SD 16.6 P = 0.005), whilst the second, Krumholz 2002 reported a reduction in bed days for cardiovascular readmissions including heart failure (mean days 6.3, SD 9.2, vs. 12.3, SD 14.3, P=0.03 test not given) but not for heart failure readmissions alone (mean days 4.1, SD 6.4 vs. 7.6, 12.1, P = 0.1, not significant).

Multidisciplinary management may also lead to a reduction in hospital bed days in the first 90 days after discharge: Rich 1995 found a significant reduction in total unplanned hospital bed days at six months in the intervention group compared to the control group. There is no evidence from the two studies to date that clinic models are associated with any reduction in days spent in hospital during follow up (Doughty 2002; Ekman 1998).

Length of time between index hospital discharge and unplanned re-admission

Three studies reported on the time between discharge and re-admission. Cline (Cline 1998, case management intervention, unclear quality) reported a significant increase in the mean length of time to re-admission in the intervention group in survivors at one year of follow up. Rainville’s extremely small case management study reported that time to re-admission or death was longer in the intervention group.

Doughty (Doughty 2002) noted no significant difference in mean time to re-admission in the clinic managed group compared to the control group.

Health Related Quality of Life

Health related quality of life (HRQL) was the principal outcome of two case management studies (Harrison 2002; Jaarsma 2000) and was mentioned as a secondary outcome in six other studies.

Harrison’s case management study (Harrison 2002, moderate quality) was powered to be able to detect a clinically significant difference in the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ), she found significant improvements in the total MLHFQ score in the intervention group compared to the control group at six and 12 weeks follow up. Jaarsma’s largely educational case management intervention study (Jaarsma 2000) suffered severe attrition and was assessed to be of lower quality - no difference in HRQL between intervention and control groups was noted. In a randomly selected sub-sample of 68 patients Stewart found a statistically significant difference in change in MLHFQ favouring the intervention group in survivors at three months but not at six months (Stewart 1999a). A fourth case management intervention study (Kasper 2002) found a clinically significant improvement in MLHFQ scores after six months follow up in intervention patients compared to controls. Cline reported no difference in Quality of Life in Heart Failure Questionnaire scores at 12 months between intervention and control groups (Cline 1998) and McDonald 2002 found no improvement in HRQL at three months follow up but the method of measurement was not described.

Rich noted greater improvements in quality of life using the Chronic Heart Failure Questionnaire in those who received his multidisciplinary intervention amongst a subset of 126 patients; it is not known how these patients were selected nor how similar the two groups were at baseline, nor is it clear whether this difference is clinically important, although this seems likely.

Only one study of a clinic model intervention reported HRQL (Doughty 2002). There was no difference in MLHFQ total scores between intervention and control patients at one year, although the physical score showed a significantly greater improvement in the clinic managed patients compared to the control group. Capomolla measured quality of life in his day hospital managed patients compared to his control group using the time trade off method and found that the intervention group had significantly higher quality of life (see Table 3).

Cost Analyses

Only one study included a formal economic evaluation (Capomolla 2002), this report of a day hospital based heart failure programme intervention found the intervention saved $1,068 with every quality adjusted life year (QALY) gained with the intervention (see Table 3). Six of the other studies presented some cost data although the type of cost data, and the way it was presented, varied (Cline 1998; Kasper 2002; Krumholz 2002; Laramee 2003; Rich 1995; Stewart 1999a). No studies reported significant differences between intervention and control groups in the costs examined however all but one study (Kasper) found that the type of cost they reported was lower in the intervention group.

Adverse Events

None of the studies noted any adverse events arising from their interventions.

Generalisability of the results

To estimate the generalisability of results to all patients with heart failure admitted to hospital we considered the proportion of patients who were eligible for the interventions out of those screened and the proportion of eligible patients who were entered into the trials. These data were not always available. Two different interventions deliberately targeted patients considered to be at high risk of re-admission (Kasper 2002; Rich 1993; Rich 1995). In Rich’s 1995 multidisciplinary study 70% of patients who fulfilled his diagnostic criteria for CHF were considered to be at moderate or high risk of re-admission. However, 57% of these subjects were excluded and only 31% of the eligible patients were included in the study (22% of all the patients with CHF). In Kasper’s case management study, 67% of heart failure patients screened were considered to be at high risk of re-admission; 70% of these had one or more exclusion criteria and 20% of the eligible patients participated in the study (14% of all the patients with CHF). Ekman’s feasibility study (Ekman 1998) found that only 17% of 1058 consecutively screened subjects with a diagnosis of CHF or cardiomyopathy met the study eligibility criteria and only 13% of the screened patients participated in the study. In the other studies the proportion of patients thought to have heart failure on admission and eligible for the study varied between 32% (Rainville 1999) and 77% (Laramee 2003) and the proportion of potentially eligible patients who participated varied between 33% (Jaarsma 2000) and 80% (McDonald 2002).

DISCUSSION

This review systematically evaluated 15 different disease management interventions targeted at patients who have already experienced one hospital admission for heart failure. We recognise that high quality and definitive evidence for service delivery interventions such as, disease management, has challenges beyond that of drug or device-based treatments and we found that attempting to synthesise the results of trials of complex interventions like these presents particular difficulties compared to the synthesis of trials of simple interventions. We attempted to divide the different interventions into three disease management models proposed by Reigel (Riegel 2001): multidisciplinary; case management; and clinic. We recognise that there may be some overlap between these models and that some interventions are difficult to classify. Our understanding of the nature of the interventions was limited to published accounts. Most of the studies concern case management type interventions, although the content, intensity and duration of these interventions varied considerably. Only two studies have examined clinic interventions and there is only one RCT of a multidisciplinary intervention as defined by Riegel.

Although nine of the 16 studies appeared to be of at least moderate quality only seven studies definitely practiced allocation concealment and the outcome assessor was known to have been masked in only five studies. Only two studies mentioned how deaths and readmissions associated with heart failure were determined and none reported how this assessment was validated. The studies reported a wide variety of different outcomes and where only a few of the studies report a particular outcome there is the possibility of publication bias. It should also be noted that all but one of the studies were conducted in a single centre and all involved a selected population and it is not clear whether the benefits seen in these trials can be extrapolated to the wider population of patients with heart failure in whom co-morbidity is common (Havranek 2002).

Case Management interventions

All but one of these interventions involved telephone follow up from a respiratory nurse to the patient at home and many had a major educational component but the interventions did vary in their other components and their duration. The proportion of patients admitted with CHF who were eligible for the studies varied between 32% and 77% and the proportion of eligible patients who participated varied between 33 and 80%. There is some evidence from pooling the data in the highest quality studies that all cause mortality may be reduced with case management. No information was available on whether or not deaths associated with heart failure are influenced by case mmanagement Survival at six months follow up without death or unplanned readmission to hospital was reported in only one study but was significantly greater in the case managed group. From the studies that have been reported it is not clear whether survival without readmission to hospital for heart failure is influenced by case management at three and six months follow up, but two moderate quality case management studies reported very similar hazard ratios in favour case management at twelve months follow up. To date there is little evidence that all cause readmissions are significantly reduced by case management. There is however, some evidence from pooling the data that readmissions for heart failure may be reduced by case management, however because of the reservations described earlier this conclusion is tentative. There is little evidence that case management reduced the days spent in hospital during readmissions for any cause, but evidence from one study that days spent in unplanned readmissions may be reduced and evidence from two other studies that days spent in readmissions associated with heart failure or other cardiovascular problems may be reduced. There is also evidence that health related quality of life, as measured by the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ) may be increased in patients receiving case management. The cost analyses are difficult to interpret and the data are sparse but suggest that case management interventions might be associated with cost reductions.

Clinic interventions

From the very scant evidence available, two studies both of which are likely to have lacked sufficient statistical power, there is almost no evidence of any benefit from clinic interventions. One of the two studies suggests that clinic based interventions are not feasible for elderly patients with a history of hospital admission for heart failure.

Multidisciplinary interventions

There is evidence from only one study on multidisciplinary type interventions. This suggests that a multidisciplinary type intervention may not improve event free survival, that is survival without admission to hospital for any reason, in the short term. This was the study’s primary endpoint and it appears to have had ssufficientstatistical power to examine this outcome. However the same study suggests that heart failure related re-admissions may be reduced in the short term (three months), but not the longer term (nine months), and hospital bed days may be reduced in the short term. It is not clear how generalisable these results might be - only 31% of the eligible patients were included in the study.

Day hospital Based Programme

The single study of a day hospital based heart failure programme directed at a very particular patient population (relatively young, male and many awaiting heart transplantation) showed a reduction in deaths from cardiac causes and hospital readmissions in the group receiving the intervention. A cost utility analysis suggested that over US$1000 would be saved with every quality adjusted life year (QALY) gained with the intervention, however the quality of this study is unclear and its results may not be generalisable.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

The data abstracted from this review form an insufficient basis for the formulation of firm recommendations for practice. Common components of most of the different disease management models appear to be the involvement of a specialist nurse, telephone follow up and patient education. Of the models examined most evidence concerns case management type interventions. There is some evidence that case management interventions may confer benefit in terms of overall survival and a tentative suggestion that they might be associated with a reduction in hospital readmissions for heart failure. Individual studies of case management interventions have shown some long term benefits in terms of unplanned hospital re-admissions or heart-failure related readmissions in single centre trials on selected study populations. There is also evidence that some case management interventions may be aassociatedwith improvements in health related quality of life. A single RCT of a multidisciplinary intervention showed evidence of benefits in terms of reduced heart-failure related re-admissions in the short term. There is at present insufficient evidence to support clinic based interventions and evidence from one feasibility study that they may not be feasible for heart failure patients.

Implications for research

Future studies of adequate sample size should include:

-

(1)

Multi centre RCTs looking at implementation of well-defined case management interventions or multidisciplinary interventions on study populations that are typical of patients admitted with CHF and which do not automatically exclude those patients living in residential care;

-

(2)

Comparisons between different interventions, particularly comparisons of interventions which have short duration (usually around discharge) and those which have a much longer duration;

-

(3)

The effect of interventions on patients’ and carers’ quality of life and their satisfaction with the interventions;

-

(4)

The cost effectiveness and cost-utility of interventions;

-

(5)

An examination of the core elements of these types of interventions.

There is a need establish sensitive and meaningful outcomes for these sort of disease management programmes.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Intense monitoring of patients with chronic heart failure following discharge from hospital - more studies needed

Patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) are often admitted to hospital as an emergency. The authors looked at 16 clinical trials that tested different ways of organising the care of CHF patients after they leave hospital. Only one of these trials was determined to be of high quality. There was some weak evidence that the intense monitoring of patients following discharge from hospital might improve survival and reduce the number of hospital readmissions. This type of care usually involved home visits and follow up telephone calls from specialist nurses. More research is needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to than the following authors and researchers for their assistance:

Avitall B, Doughty RN, Ekman I (Ekman 1998), Hardman S, Harrison MB (Harrison 2002), Jaarsma T (Jaarsma 2000), Kasper EK (Kasper 2002), Krumholz HM (Krumholz 2002), Laramee AS (Laramee 2003), Massie B, McDonald K (McDonald 2002), Moser D, Rainville EC (Rainville 1999), Rich MW (Rich 1993; Rich 1995), Thompson DR

We are also grateful to Library Services at Queen Mary, University of London and to the following individuals: D Ashby, statistician; F Benato (assistance with reports in Spanish and Italian); A Besson, librarian; F Cason (assistance with reports in German); S Eldridge, statistician; A Spenser, economist and S Das; J Formby; E Hallgarten; A Langdon for assistance with searches or administrative support.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

ELENOR (East London and Essex Network of Researchers), UK.

DoH (Department of Health) Public Health Career Scientist Award, UK.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT, single centre Recruiting: March 1997 to November 1998. Duration of follow up: 12 months (mean follow up) |

|

| Participants | Country: Scotland Participants: 81 patients (41 males, 51%) in comparison group, 84 (54 males, 64%) in intervention group Actual age of study subjects: usual care mean 75.6 years (SD 7.9), intervention 74.4 years (SD 8.6). Male sex: 58% Ethnicity: not given Actual severity of heart failure in study subjects at recruitment: NHYA class, n,: control group II 16 (20%), III 33 (42%), IV 30 (35%), intervention group II 19 (23%), III 28 (34%), IV 36 (43%) LVEF: not given Study inclusion criteria: Patients admitted as an emergency to the acute medical admissions unit at one hospital with HF due to LV systolic dysfunction Study exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Duration of intervention: up to 12 months Intervention Group: “Specialist nurse intervention” During index hospitalisation: Patients were seen by a HF nurse prior to discharge. After discharge: Home visit by HF nurse and within 48 hours of discharge Subsequent visits by HF nurse at 1, 3, and 6 weeks and at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. Scheduled phone calls at 2 weeks and at 1, 2,4,5,7,8,10 and 11 months after discharge. Patients and their families encouraged to contact nurses with problems or questions by phone during office hours (answering machine where they could leave messages after hours). Additional unscheduled home visits and telephone contacts as required Home visits covered: Patient education about HF and its Rx, self-monitoring and management (especially the early detection and treatment of decompensation). Patients were given a booklet about HF which included a list of their drugs, contact details for HF nurses, blood test results and clinic appointment times. The trained HF nurses used written drug protocols and aimed to optimise patient treatment (drugs, exercise and diet) and HF nurses also provided psychological support to the patient. HF nurses liaised with the cardiology team and other health care and social workers as required Comparison Group: usual care “Patients in the usual care group were managed as usual by the admitting physician and, subsequently, general practitioner. They were not seen by the specialist nurses after discharge.” |

|

| Outcomes | Primary endpoints: Unplanned re-admissions within 90 days of discharge. Total number of days hospitalised during follow up. Also looked at: Re-admission rates in the moderate risk subgroup compared to the high risk sub group Analysis done on intention to treat basis?: yes* |

|

| Notes | Data source: published data only Generalisability: 801 patients thought to have heart failure on admission were screened; 361 (45%) were eligible for the study and survived to have echocardiography; 12 (3%) refused consent; 184 (51% of 361) did not have LV systolic dysfunction; and 165 (46%, 21% of those screened) of these were randomised Consort flow chart: supplied. Rationale for sample size: given. Other points: Reasons for exclusions: proportions of patients with different reasons for exclusion not given Data on hospital admissions and deaths obtained both from the hospital records department and from the information and the statistics division of the Scottish NHS (admissions) and the Registrar General’s Office, Scotland (deaths) Generation of randomisation sequence and allocation concealment: “Study nurses phoned the Robertson Centre for Biostatistics and the patient was allocated to one or other randomisation group from a randomisation list.” Risk of care giver performance bias: possible, since HF nurses did not see control patients but hospital cardiology team may have been aware of randomisation group of patients. Risk of attrition bias: low. Risk of detection bias: low, “all hospital admissions were adjudicated blind to treatment” by a masked endpoint committee |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | RCT, single centre Recruitment: January 1999 to January 2000. Duration of follow up: mean follow up of 12 months |

|

| Participants | Country: Italy Participants: 122 patients (102 males, 84%) in comparison group, 112 (94 males, 84%) in intervention group Actual age of study subjects: mean age 56 years (SD 10) Male sex: 84% Ethnicity: not given. Actual severity of heart failure in study subjects at baseline: NYHA class I-II/III-IV: 158/81 (68% I-II) LVEF: 29% (SD 7) Study inclusion criteria:

Study exclusion criteria: None given. |

|

| Interventions | Duration of intervention: not clear. Intervention Group: Comprehensive Heart Failure Outpatient Management Program delivered by the day hospital During index hospitalisation: cardiac prognostic stratification and prescription of individual tailored therapy following guidelines and evidence After discharge: Attendance at day hospital staffed by a multidisciplinary team (cardiologist, nurse, physiotherapist, dietician, psychologist and social assistant). Patient access to the day hospital ’modulated according to demands of care process’. Care plan developed for each patient. Tailored interventions covering: cardiovascular risk stratification; tailored therapy; tailored physical training; counselling; checking clinical stability; correction of risk factors for haemodynamic instability; and health care education. Patients who deteriorate re-entered the day hospital through an open-access programme Day hospital also offered: intravenous therapy; laboratory examinations; and therapeutic changes as required The education given covered: knowledge about CHF and drug treatments and self management including daily weights, fluid restriction and nutrition Comparison Group: usual care During admission: cardiac prognostic stratification and prescription of individual tailored therapy following guidelines and evidence After discharge: ’The patient returned to the community and was followed up by a primary care physician with the support of a cardiologist’ |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: Readmissions because of haemodynamic instability. Deaths from cardiac causes. Cardiac mortality and urgent heart transplant Secondary outcomes: ‘Tailored therapy management’ QOL NYHA functional class Also looked at: Cost utility of the two strategies. Analysis done on intention to treat basis? Not clear |

|

| Notes | Data source: published data only Generalisability: 234 patients admitted the HFU with a diagnosis of CHF; 234 randomised (100%) Consort flow chart: not supplied Rationale for sample size: not given Other points: No patients excluded from study. Generation of randomisation sequence and allocation concealment: no information supplied Risk of care giver performance bias: unclear. Risk of attrition bias: unclear Risk of detection bias: likely because after 12 months all patients were re-evaluated in the Heart Failure Unit and the Day Hospital is part of this unit |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | B - Unclear |

| Methods | RCT, single centre Recruitment: December 1991 to October 1993. Duration of follow up: 12 months. |

|

| Participants | Country: Sweden Participants: 110 patients (57 males, 52%) in comparison group, 80 (44 males, 55%) in intervention group. Actual age of study subjects: mean 75.6 years (SD 5.3) Male sex: 53% Ethnicity: not given Actual severity of heart failure in study subjects at baseline: NYHA class, mean: controls 2.6 (SD 0.7), intervention group 2.6 (SD 0.7) LVEF: control group mean 35.7% (SD 12.3), intervention group 31.6% (SD 8.4). (75% LVEF <40%) Study inclusion criteria:

Study exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Duration of intervention: 12 months Intervention Group: “Management programme for heart failure” During index hospitalisation: Patients received an education programme from HF nurse consisting of two 30 minute visits After discharge: Two weeks after discharge patients and their families were invited to a one hour group education session led by the HF nurse which included an oral presentation by the nurse, and educational video and a question and answer session. Patients were also offered a seven day medication dispenser if deemed appropriate. Patients were followed up at a nurse directed o/p clinic and there was a single prescheduled visit by the nurse at 8 months after discharge. The HF nurse was available for phone contact during office hours. Patients encouraged to contact the study nurse at their discretion, if unsure, if diuretic adjustments did not ameliorate symptoms in 2-3 days, or if there were “profound changes in self management variables”. Patients were offered cardiology outpatient visits one and four months after discharge The inpatient and outpatient education programme covered: HF pathophysiology, pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment. Patients were also given guidelines for self-management of diuretics in the event of fluid overload or fluid depletion. Patients were given a “heart failure diary” containing information on HF, list of HF medications, names and contact phone numbers for the HF clinic and in which to regularly record bodyweight, ankle circumference and HF symptoms Comparison Group: usual care These patients were “followed up at the outpatient clinic in the department of cardiology by either cardiologists in private practice or by primary care physicians as considered appropriate by the discharging consultant.” |

|

| Outcomes | Primary endpoint: Not specified, abstract states that main outcome measures were: time to re-admission, days in hospital and health care costs during one year Other endpoints: Quality of life using The Quality of Life in Heart Failure Questionnaire, Nottingham Health Profile and patients’ global self assessment (all self-administered) Also looked at: Deaths at 90 days Event free (i.e. death or re-admission) survival at 90 days Analysis done on intention to treat basis?: unclear |

|

| Notes | Data source: published data only Generalisability: no information supplied on number of patients screened for entry to the study or on the number of patients excluded. 206 eligible patients were randomised before consenting, 16 patients (8%) randomised to the intervention group withheld their consent, no patient randomised to the control group withheld consent Consort flow chart: not supplied Rationale for sample size: not given Other points: Reasons for exclusions: proportions of patients with different reasons for exclusion not given Generation of randomisation sequence: computer generated random allocation. Allocation concealment: “Patients were invited to participate and informed consent was given on the basis of information relevant to the allocated study group. This procedure avoided bias arising from control patients being informed of the intervention strategy.” Risk of care giver performance bias: possible that some of the control patients were also seen by cardiologists involved in the study. Risk of attrition bias: low “all patients were accounted for”. Risk of detection bias: possible, not clear who collected data on patients and not clear if this data collection was masked |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | B - Unclear |

| Methods | Cluster RCT, GP as the unit of randomisation (but see note), single centre. Recruitment: during 1997 and 1998. Duration of follow up: 12 months. |

|

| Participants | Country: New Zealand Participants: 97 patients (54 males, 56%) in comparison group, 100 (64 males, 64%) in intervention group. Actual age of study subjects: mean 73 years (SD 10.8, range 34 to 92 years). Male sex: 60% Ethnicity: ‘NZ European’ 79% Severity of heart failure in study subjects: (At index admission) NYHA class, n (%): controls II 24 (25%), III 73 (75%), intervention group II 24 (24%), III 76 (76%). (At baseline) LVEF: control group mean 33.8% (SD 12.7), intervention group 30.6% (SD 12.7) Study inclusion criteria: Patients admitted to general medical wards with a primary diagnosis of heart failure Study exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Duration of intervention: 12 months Intervention Group: ‘integrated heart failure management programme’ After discharge: Outpatient review at heart failure clinic within 2/52 of discharge from hospital: clinical status reviewed, pharmacological treatment based on evidence based guidelines, one-to-one education with study nurse, education booklet provided. Patient diary for daily weights, Rx record & clinical notes provided. Detailed letter faxed to GP and follow up phone call to GP. GPs encouraged to discuss management with clinic team. Follow up plan aiming at 6 weekly visits alternating between GP and HF clinic. Group education sessions for patients run by cardiologist and study nurse: two sessions offered within 6 weeks of discharge and one at 6 months post d/c. Telephone access to study team for GPs or patients during office hours Group education sessions covered: education about disease; monitoring daily body weight and action plans for weight changes; medication; exercise; diet. Comparison Group: usual care |

|

| Outcomes | Primary endpoints: Time to first event i.e. death or hospital re-admission. HRQL measured using Minnesota Living With Heart Failure Q at baseline and 12 months Other endpoints: All cause hospital re-admissions. Heart failure related hospital re-admissions. All cause hospital bed-days Also looked at: Medications at 12 months Analysis done on intention to treat basis?: yes |

|

| Notes | Data source: published data only Generalisability: does not report how many patients were screened for eligibility to study, nor how many of those deemed eligible agreed to participate Consort flow chart: not supplied Rationale for sample size: given but sample size calculation not verifiable from information given and no mention of adjustment of sample size calculation from cluster randomised design. (Study terminated early before sample size achieved.) Other points: Reasons for exclusions: proportions of patients with different reasons for exclusion not given. Randomisation: GPs were randomised before participant recruitment - possibility that team were aware of assignment of GP before recruitment of patient into study. Generation of randomisation sequence and allocation concealment: “General practitioners were randomly allocated using computer generated random numbers…after consent was obtained the patient was informed of their group allocation based on the randomisation of their current general practitioner.” Care giver performance bias: unclear; primary care giver performance bias unlikely because to avoid contamination of GPs a cluster RCT design was employed. However, not clear whether hospital staff managed both intervention and control patients. Risk of attrition bias: low Risk of detection bias: possible, no mention of blinding of those assessing endpoints |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | B - Unclear |

| Methods | RCT, feasibility study, one centre Recruitment: November 1994 to January 1996. Duration of follow up: mean follow up time 5.0 months (SD 2.0) control group and 5.0 (2.3) in the intervention group |

|

| Participants | Country: Sweden Participants: 79 patients in comparison group, 79 in intervention group, males: females in each group not given. Actual age of study subjects: mean 80.3 years (SD 6.8) Male sex: 58% Ethnicity: not given Actual severity of heart failure in study subjects at recruitment: NYHA class: control group mean 3.2 (SD 0.5), intervention group 3.2 (SD 0.5) LVEF on 99 patients (63%): control group mean 38% (SD 25), intervention group 43% (SD 18) Study inclusion criteria:

Study exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Duration of intervention: 6 months? Intervention Group: ‘Structured care programme based on Nurse-monitored outpatient clinic’ After discharge: Pt and carers offered visit to specialist nurse monitored HF clinic one week after discharge, clinic run in collaboration with the study doctors (who were responsible for pharmacological Rx). Main aim of programme was patient education about their treatment and the symptoms of clinical deterioration. Tailored care plan with individualised treatment goals for each patient. Primary care team continually informed about patient’s situation by HF clinic nurses. Patients had access to clinic nurses during business hours. In emergencies patients seen by clinic nurses and attending doctor Patients given notebook for daily weight monitoring, treatment and information about clinical deterioration. Clinic nurses made regular follow up telephone calls to patients, those not seen regularly in clinic were called monthly Comparison Group: usual care. In general this was GP follow up. |

|

| Outcomes | Main endpoints: Proportion of patients aged > 65 years who were eligible for the study. Proportion of patients in the intervention group who did not visit the HF nurses. NYHA functional class. Hospitalisations and hospital days during six month follow up. Deaths. Analysis done on intention to treat basis?: yes |

|

| Notes | Data source: published data and information from author* Generalisability: Of 1058 consecutively screened patients with a diagnosis of heart failure and cardiomyopathy and aged 65 years or older, only 160 (17%) met criteria for participating in the study (2 later found not to be eligible) and 22 (12%) of these refused to participate Consort flow chart: not supplied Rationale for sample size: not given, feasibility study Other points: Reasons for exclusions (sub study of 454 excluded patients): 27% had serious communication problems or were otherwise too disabled to attend the out patient clinic, 25% had Boston criteria score <8, 18% NYHA class <III, 8% nursing home care, 7% specialist care, 5% acute MI Generation of randomisation sequence: “randomly permuted blocks with a size of 20 obtained from tables of random numbers.”. Allocation concealment: “consecutively numbered, sealed envelopes containing group assignments”. The envelopes were generated by a doctor but allocated by a nurse Risk of care giver performance bias: high; 20 care likely because the three specialist nurses who staffed the HF clinic also staffed the inpatient ward, 10 care both control and intervention patients’ general practitioners were aware their patients were in the study* and they must have known the allocation group of their patients. Risk of attrition bias: low Risk of detection bias: high, those collecting endpoint data were not masked to patients’ allocation status* |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | RCT, single centre Study recruitment: June 1996 to January 1998. Duration of follow up: 12 weeks. |

|

| Participants | Country: Canada Participants: 100 patients (56 males, 56%) in comparison group, 92 (49 males, 53%) in intervention group. Actual age of study subjects: mean age 76 years, median age 77 years (range 33-93 years). Male sex: 55% Ethnicity: not given. Severity of heart failure in study subjects: NYHA class, n (%) at baseline: controls: I 2 (2%), II 20 (20%), III 69 (69%), IV 8 (8%); intervention group: I 0, II 21 (23%), III 60 (65%), IV 11 (12%) LVEF: not given Study inclusion criteria:

Study exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Duration of intervention: 2 weeks following discharge. Intervention Group: Transitional care (TC) Before discharge: Standard discharge planning and care (see below). Comprehensive, evidence based education programme for heart failure self-management (PCCHF). A nursing transfer letter to the home care nurse detailing clinical status and self-management needs After discharge: Phone call from hospital nurse to patient within 24 hours of discharge. Minimum of two community nurse visits within two weeks of discharge Content of PCCHF: Patient workbook covering: the disease, self-monitoring, management of medication, diet, exercise, stress, support systems and community resources. Allowed tailoring for individual needs. Also contained an education plan and served as a patient held documentation tool Comparison Group: usual care discharge planning and ‘optimal’ usual post discharge care. Before discharge: Ideally a multidisciplinary discharge plan within 24 hours of admission and weekly discharge planning meetings. Regional home care co-coordinator consults with hospital team as required and may meet patients and their families. Immediately before discharge physician completes referral form for home care and necessary services and supplies are communicated with the home nursing agency After discharge: Number of home visits scheduled to match those received by TC group |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: HRQL measured by the MLHFQ 6 and 12 weeks post discharge. Secondary outcomes: QOL measured with SF-36. Number of all-cause emergency room visits. Number of all-cause hospital re-admissions. Analysis done on intention to treat basis?: no “Eleven individuals were readmitted to hospital during the intervention period. Timing for outcome measures then began on second discharge and followed for 3 months. ” Also, eight patients who dropped out after randomisation were not included in the study |

|

| Notes | Data source: published data and information from author*. Generalisability: 483 patients thought to have heart failure admitted; 212 (44%) were eligible for the study; 12 (6%) refused consent. After randomisation 8 more patients (5 TC and 3 usual care) did not enter the study: four died or became too ill; two refused home care; one changed diagnosis and one was discharged to long term care. 192 patients (40% of admissions) were entered into the study, of these only 157 (82% of those considered entered into study, 78% of those randomised) were followed up Consort flow chart: not supplied Rationale for sample size: given Other points: Reasons for exclusions (271 patients): coming from/ being discharge to long term care (38%); living outside the catchment area (23%); too ill or deceased shortly after admission (15%); first language not French or English (12%); discharged with in 24 hours (6%); diagnosis changed (3%); other (3%) Not clear whether, or how many of, the eleven readmitted and re-entered patients were in intervention or control groups. Generation of randomisation sequence: computer generated schedule. Allocation concealment: “pre-packaged, consecutively numbered, sealed opaque envelopes containing the group allocation were prepared for each nursing unit and administered from the research office. Neither the patients nor the members of the study team were aware of treatment assignment until after randomisation.” Care giver performance bias comment: bias possible since hospital nurses provided both experimental and control interventions and all care givers in the community were informed that patients were in the intervention or control groups after randomisation*. Risk of attrition bias: likely. Only 157 patients (82% of those considered entered into study, 78% of those randomised) were followed up. 23 UC patients and 12 TC patients not followed up, reasons: died or too ill (11 UC, 9TC); withdrew (7 UC, 1 TC); lost to follow up (5 UC, 2 TC). Risk of detection bias: low, outcome assessors masked*. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | RCT Recruitment: May 1994 to March 1997. Duration of follow up: 9 months. |

|