Abstract

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), the accumulation of β-amyloid (Aβ) peptides in the walls of cerebral blood vessels, is observed in the majority of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) brains and is thought to be due to a failure of the aging brain to clear Aβ. Perivascular drainage of Aβ along cerebrovascular basement membranes (CVBMs) is one of the mechanisms by which Aβ is removed from the brain. CVBMs are specialized sheets of extracellular matrix that provide structural and functional support for cerebral blood vessels. Changes in CVBM composition and structure are observed in the aged and AD brain and may contribute to the development and progression of CAA. This review summarizes the properties of the CVBM, its role in mediating clearance of interstitial fluids and solutes from the brain, and evidence supporting a role for CVBM in the etiology of CAA.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, perivascular drainage, basement membrane, β-amyloid

Alzheimer’s Disease and Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic progressive neurodegenerative disease, currently estimated to affect 35.2 million people worldwide, making it the commonest form of dementia (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2014). Life expectancy after diagnosis ranges from 4 to 6 years (Larson et al., 2004). The main risk factor is age, with the chance of developing AD doubling every 5 years after the age of 65 years (Gao et al., 1998). Other non-modifiable risk factors include mutations in genes encoding the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and presenilin-1 and -2 in familial AD cases (Tanzi, 2012) and possession of the apolipoprotein E (ApoE) ε4 allele in sporadic AD (Tanzi, 2012). Midlife hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia are modifiable risk factors that increase the risk of developing AD in late life (Launer et al., 2000; Shah et al., 2012).

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized clinically by a slow and gradual deterioration in cognitive function as well as psychiatric symptoms and behavioral disturbances such as depression, delusions, and agitation (Burns, 1992; Bird and Miller, 2007). Neuropathologically, AD is associated with brain region-specific neuronal loss and synaptic degeneration (Bondareff et al., 1982; Whitehouse et al., 1982; Vogels et al., 1990; Aletrino et al., 1992), which begin in the entorhinal cortex and advance to the hippocampus and posterior temporal and parietal cortices (Begley et al., 1990; Braak and Braak, 1991). The end result of this degenerative neuronal loss is brain shrinkage and ventricular enlargement.

Two classical pathological features of AD are the accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and senile plaques (Braak and Braak, 1991; Alafuzoff et al., 2008). NFTs are formed predominantly of ubiquitinated hyperphosphorylated tau (Esiri et al., 2004). Tau is a microtubule-associated protein that is present in mature neurons. In AD, tau becomes hyperphosphorylated and aggregates into NFTs of paired helical filaments (Iqbal et al., 2010). These aggregated bundles are seen pathologically as intraneuronal tangles in dystrophic neurites surrounding senile plaques and in the neuropil as neuropil threads (Braak et al., 1986; Grundke-Iqbal et al., 1986). Senile plaques are formed predominantly of amyloid β (Aβ). Amyloidogenic Aβ is produced from the sequential cleavage of APP by two proteases, β- and γ-secretase.

In addition to its deposition in the parenchyma, Aβ accumulates in the walls of cerebral blood vessels as cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) (Miyakawa et al., 1982; Vinters, 1987; Weller et al., 2008). CAA is observed in 30–40% of non-demented elderly individuals and 60–95% of AD brains studied at autopsy (Vinters, 1987; Castano and Frangione, 1988; Haan et al., 1991; Jellinger, 2002). It affects predominantly leptomeningeal and cortical arteries but also occurs in cerebral capillaries (Vinters, 1987; Giannakopoulos et al., 1997; Roher et al., 2003). Unlike the parenchymal senile plaques that are composed principally of Aβ42 (Dickson et al., 1988), vascular Aβ deposits comprise predominantly Aβ40 (Suzuki et al., 1994). CAA is associated with capillary thinning and vessel tortuosity, inhibition of angiogenesis, and the death of pericytes, endothelial, and smooth muscle cells (Perlmutter et al., 1994; Miao et al., 2005; Haglund et al., 2006; Tian et al., 2006; Burger et al., 2009). Cerebral hypoperfusion, microhemorrhages, and cognitive impairment have also been shown to be associated with CAA severity (Natte et al., 2001; Pfeifer et al., 2002a,b; Shin et al., 2007; Chung et al., 2009).

The origin of the vascular Aβ deposits has been contested since the early twentieth century when it was first proposed that blood-borne Aβ was causing the phenomenon (Scholz, 1938). In the presiding half-century, other mechanisms were suggested, including the production of Aβ by vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) (Wisniewski and Wegiel, 1994; Vinters et al., 1996; Wisniewski et al., 1996). However, the dichotomy between the specific localization of CAA to cerebral blood vessels and the ubiquitous expression of VSMCs throughout the body, suggested a brain-based origin of vascular Aβ. This hypothesis was supported by findings that transgenic mice producing mutant human Aβ only in the brain develop CAA (Herzig et al., 2004, 2006).

Based in part on electron microscopy studies showing the deposition of Aβ within the cerebrovascular basement membrane (CVBM) of the arterial tunica media (Wisniewski and Wegiel, 1994), Weller et al. (1998) hypothesized that parenchymal Aβ is normally cleared from the brain along CVBM and that CAA results from the failure of this system in the aged brain.

This review will summarize the properties of the CVBM, its role in mediating clearance of interstitial fluid (ISF) and solutes from the brain, and evidence supporting a role for CVBM in the etiology of CAA.

The Basement Membrane of the Brain

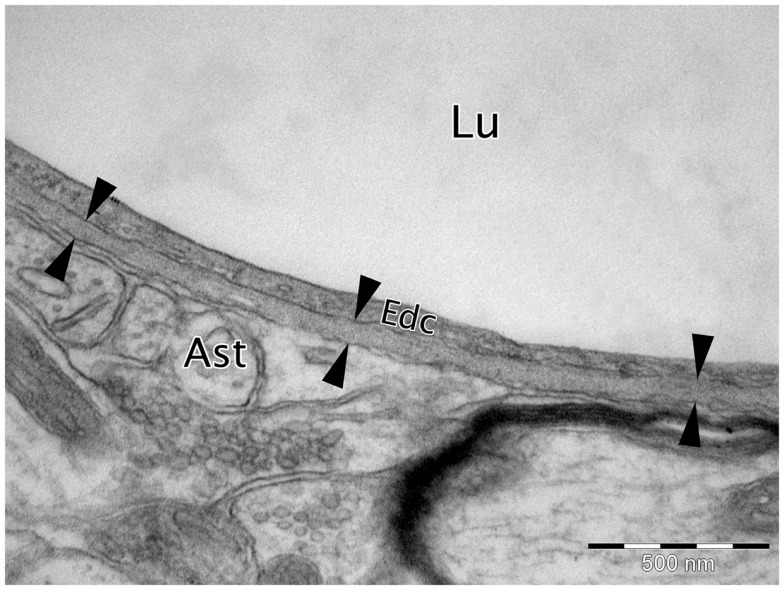

Basement membranes (BMs) are specialized extracellular matrices 50–100 nm in size when visualized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) that cover the basal aspect of all endothelial and epithelial cells and surround fat, muscle, and Schwann cells (Carlson et al., 1978; Yurchenco and Schittny, 1990; Weber, 1992; Timpl, 1996; Miner, 1999; Candiello et al., 2007; McKee et al., 2009; Rasi et al., 2010) (Figure 1). They are formed from a variety of intracellularly produced proteins that are secreted into the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM). BMs provide structural support to tissues, separate cells from connective tissue, and are important in modulating cellular signaling pathways (Yurchenco and Schittny, 1990; Timpl and Brown, 1996; Kalluri, 2003). The majority of BMs contain the following proteins; type IV collagen, laminins, nidogen, and the major heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) perlecan (Timpl and Brown, 1996; Halfter et al., 2013). Each of these core BM proteins has a subset of isoforms, there are 6 isoforms of type IV collagen, 2 nidogen isoforms, 2 major HSPGs (perlecan and agrin), and 16 different isoforms of laminin (Sorokin, 2010). Variation in the structural composition of the core BM proteins results in protein heterogeneity. For example, collagen IV comprises six distinct polypeptide α-chains [α1(IV)–α6(IV)], which assemble with high specificity to form three distinct isoforms, α1α1α2, α3α4α5, and α5α5α6 (Khoshnoodi et al., 2008). Laminins are composed of α, β, and γ polypeptide chain (Miner and Yurchenco, 2004). Currently 5 distinct α chains, 3 distinct β chains, and 3 distinct γ chains have been characterized and they assemble in various combinations to form 16 different laminin isoforms, which are classified as α1β1γ1, which is abbreviated to 111, depending on which chains make up the final molecule (Aumailley et al., 2005). Auxiliary BM proteins including, type XV collagen, type XVIII collagen, agrin, osteonectin [also known as secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) or BM protein 40 (BM40)], BM90, and fibulin contribute to the structural and functional diversity of the BM across different tissues (Timpl, 1996).

Figure 1.

Micrograph of cortical Wistar Kyoto rat capillary. The cerebrovascular basement membrane is the electron dense area between the six arrow heads. Lu, capillary lumen; Edc, endothelial cell; Ast, astrocyte end foot. TEM, 50,000×, scale bar, 500 nm.

In the brain, BM proteins are expressed in the ECM of the parenchyma and within multiple layers of the cerebral blood vessels. Collagen IV (Khoshnoodi et al., 2008), laminin (Hagg et al., 1989; Hunter et al., 1992; Jucker et al., 1996a,b; Hallmann et al., 2005), nidogen -1 and -2 (Bader et al., 2005), HSPGs perlecan (Noonan and Hassell, 1993), fibronectin (Caffo et al., 2008), and agrin (Barber and Lieth, 1997), are the predominant BM constituents of the brain. However, there are variations in the composition of individual cerebral BMs, especially with regards to laminin. For example, the BM of the glia limitans contains both laminin α1 and α2 (Hallmann et al., 2005), whereas only laminin α1 is expressed in the meningeal epithelium and the astrocytic endothelium contains only laminin α2 (Hallmann et al., 2005). The different protein composition within each cerebral BM influences numerous cellular functions such as neural stem cell differentiation and migration, axon formation, apoptosis, myelination, and glial scar formation (Perris, 1997; Goldbrunner et al., 1999; Thyboll et al., 2002).

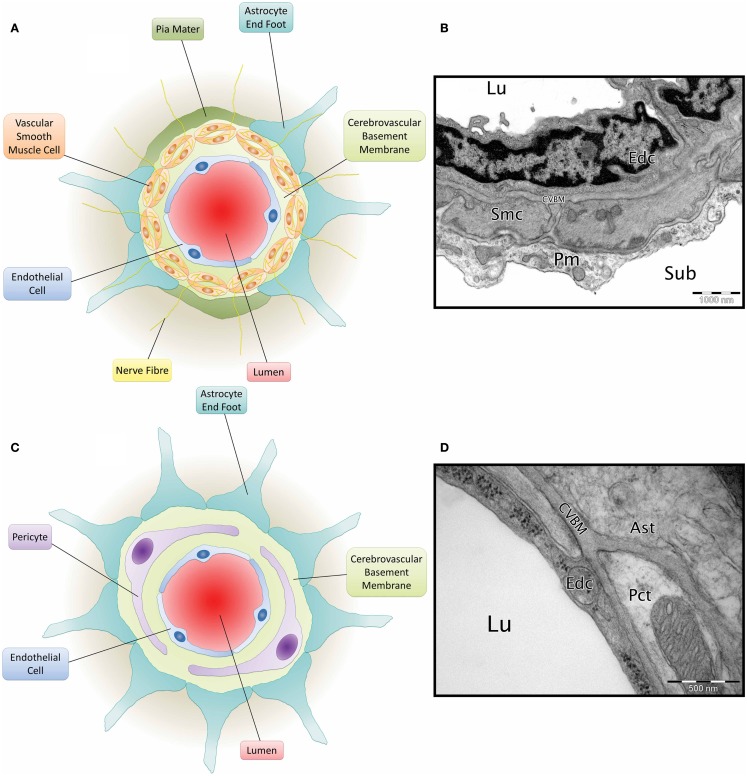

Cerebrovascular basement membranes play an important role in blood vessel development and health, formation and maintenance of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and migration of peripheral cells including leukocytes into the brain (Sixt et al., 2001; Zlokovic, 2008; Wu et al., 2009). Endothelial cells, astrocytes and smooth muscle cells (Zlokovic, 2008) all contribute to the composition of the CVBM (Yousif et al., 2013) and this also receives contributions from pericytes (Dohgu et al., 2005; Bell et al., 2010) (Figure 2). The CVBM comprises collagen IV, laminin, perlecan, and nidogen as well as several minor glycoproteins (Hallmann et al., 2005). There is, however, variation in the expression of laminin isoforms within the CVBM of different vessel types (Sorokin, 2010). At the capillary level, the BM is fused between the endothelial cells and astrocyte end feet and contains laminin α2, α4, and α5 (Hallmann et al., 2005). Cerebral arterioles and arteries contain an endothelial BM (containing laminin α4 and/or α5), a BM that surrounds the VSMCs within tunica media (containing laminin α1 and α2) and an astrocytic BM (containing laminin α1 and α2) (Sixt et al., 2001). Veins comprise an endothelial BM (containing laminin α4 and a patchy distribution of laminin α5), a smooth muscle BM (containing laminin α1 and α2), and an astrocytic BM (containing laminin α2, α4, and α5) (Sixt et al., 2001; Yousif et al., 2013).

Figure 2.

Composition of the neurovascular unit. (A) Diagram of leptomeningeal artery. Viewed from the center: arterial lumen (red), endothelial cell (blue), cerebrovascular basement membrane (light green), vascular smooth muscle cells (orange) have a cerebrovascular basement membrane running between them and are penetrated by nerve fibres (yellow), pia mater (dark green), and astrocyte end foot (teal). (B) Micrograph of C57BL/6 mouse cortical artery. Lu, lumen; Edc, endothelial cell; Smc, vascular smooth muscle cell; CVBM, cerebrovascular basement membrane; Pm, pia mater; sub, subarachnoid space. TEM, 25,000×, scale bar, 1000 nm, image credit: Matthew M. Sharp. (C) Diagram of a cerebral capillary. Viewed from the center; capillary lumen (red), endothelial cell (blue), cerebrovascular basement membrane (light green), pericyte (purple), and astrocyte end foot (teal). (D) Micrograph of Wistar Kyoto rat cerebral capillary. Lu, lumen; Edc, endothelial cell; Pct, pericyte; CVBM, cerebrovascular basement membrane; Ast, astrocyte end foot. TEM, 50,000×; scale bar, 500 nm.

Perivascular Elimination Pathway of ISF

The brain only accounts for around 2% of total body mass, but it is responsible for approximately a quarter of the body’s total oxygen and glucose consumption (Zlokovic, 2008). This metabolic output produces large quantities of waste neurotoxins that must be transported, along with other solutes, out of the brain for eventual excretion from the body. Unlike peripheral organs that communicate with the lymphatic system to remove ISF, the brain does not have conventional lymphatics. Solutes that cannot be eliminated across the BBB or into the CSF must therefore be removed via alternative routes.

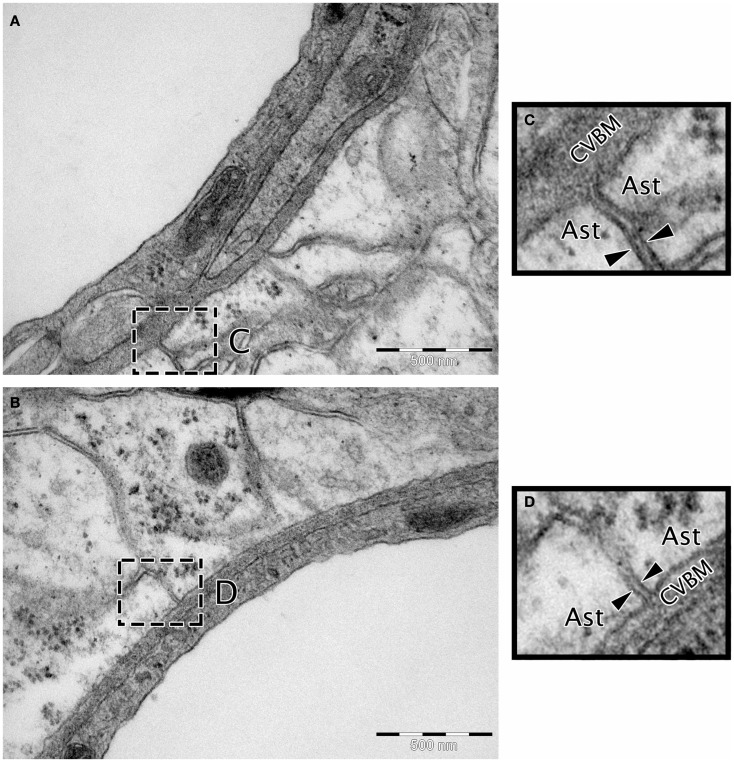

Transmission electron microscopy analyses indicate continuity between the extracellular spaces of the brain and the endothelial capillary BM (Figure 3), suggesting a putative pathway by which parenchymal ISF may be cleared. Results from early drainage studies found that large molecular weight compounds injected into the brain parenchyma spread along perivascular spaces and could be observed in the walls of leptomeningeal arteries and in cervical lymph nodes (Szentistvanyi et al., 1984). Further, the clearance of small and large molecules occurred at similar rates (Cserr et al., 1981), suggesting that movement of ISF was dependent on bulk flow rather than diffusion, with an estimated clearance rate of 0.15–0.29 μL/min/g in the rat brain and 0.10–0.15 μL/min/g in the rabbit (Szentistvanyi et al., 1984; Abbott, 2004; Carare et al., 2008).

Figure 3.

Micrographs showing the continuity between the extracellular matrix and the cerebrovascular basement membrane. (A,B) Wistar Kyoto rat cerebral capillary, TEM, 50,000× scale bar 500 nm. (C,D) Magnified insert highlighting continuity between the BM and extracellular matrix. The extracellular matrix is the electron dense area between the two arrow heads in (C,D). Ast, astrocyte end foot; CVBM, cerebrovascular basement membrane.

The role of the CVBM in the perivascular clearance of parenchymal solutes was shown experimentally by Carare et al., who found that fluorescent tracers were localized to the BM of both capillaries and arteries within 5 min of injection into the deep gray matter (Carare et al., 2008). In arterial walls, the tracers were specifically located in the BM of the tunica media, but not in the endothelial BM or the outer most BM between the arterial wall and brain parenchyma (Carare et al., 2008). At 3 h after injection, the tracer had cleared the CVBMs and tracers were only visible within perivascular macrophages (Carare et al., 2008). More recent studies using multiphoton imaging have confirmed the drainage of intracerebrally injected tracers along perivascular BMs (Arbel-Ornath et al., 2013). This pathway appears specific to small solutes, as large molecules, including immune complexes, Indian ink, and 20 nm fluorospheres are unable to enter the CVBM (Zhang et al., 1992; Barua et al., 2012; Teeling et al., 2012).

The motive force for the perivascular elimination pathway is still unclear. It has been hypothesized that cerebral blood flow plays a major role because clearance ceases immediately after cardiac arrest (Carare et al., 2008). Mathematical models have also provided insight into potential mechanisms by highlighting the potential for reflection wave driven flow (Schley et al., 2006; Wang and Olbricht, 2011). Each arterial pulsation is followed by a contrary (reflection) wave that passes along the vessel wall in the opposite direction to blood flow, which matches the observed pattern of distribution of solutes injected into the gray matter (Schley et al., 2006; Wang and Olbricht, 2011). This reflection wave could be aided by conformational changes in the CVBMs occurring during constriction and relaxation of the vessel wall in arteries (Carare et al., 2013) and of pericytes in capillaries. BM proteins may also adopt a valve-like configuration to prevent the ISF back flow (Schley et al., 2006).

Role of CVBM and Perivascular Drainage in CAA

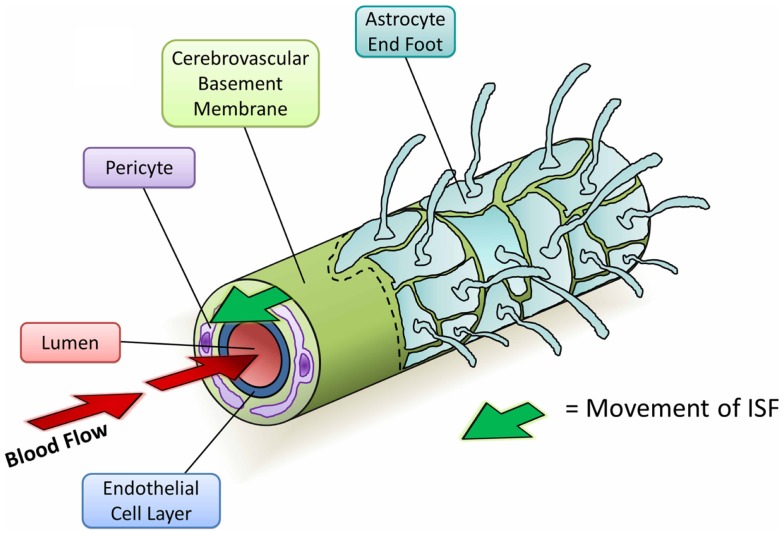

Since the initial studies into perivascular elimination of solutes, it has been shown that soluble Aβ follows the same route after injection (Figure 4) (Hawkes et al., 2011, 2012, 2013). The pattern of distribution closely matches with that of human CAA, supporting the hypothesis that CAA outlines the natural route of elimination of cerebral Aβ. Multiple additional lines of evidence suggest an important role for CVBMs in the clearance of Aβ and its failure in CAA:

Figure 4.

Diagram depicting the perivascular elimination of solutes along the cerebrovascular basement membrane of a cerebral capillary. The arterial pulsatile wave driving blood flow into the brain (red arrows) is followed by a refractory wave, which may drive the movement of interstitial fluid (ISF) out of the brain along the cerebrovascular basement membrane (green arrow). Conformational changes in cerebrovascular basement membranes during the refractory wave may provide a valve-like mechanism that promotes unidirectional flow of ISF. Viewed from the center: capillary lumen (red), endothelial cell layer (blue), cerebrovascular basement membrane (light green), pericyte (purple), and astrocyte end foot (teal) with a section removed beyond dotted line.

Morphologic changes in the cerebrovasculature and CVBM

Thickening, splitting, duplication, and the presence of abnormal inclusions in the CVBM have been reported in the brains of aged animals and humans and to a greater degree in the AD brain (Perlmutter, 1994; Kalaria, 1996; Farkas and Luiten, 2001; Shimizu et al., 2009). Thickening of the CVBM in both rodents and humans appears to be most predominant in brain areas that are susceptible to AD and CAA pathology (Zarow et al., 1997; Hawkes et al., 2013) and precedes CAA onset in TGF-β transgenic mice (Wyss-Coray et al., 2000). Further, increasing age is associated with arterial rigidity, elongation, and tortuosity, as well as a reduction in the vascular content of smooth muscle (Dahl, 1976). Such changes may diminish the force of arterial contraction and thereby diminish the driving force for perivascular clearance of Aβ.

Changes in the biochemical composition of the CVBM

Laminin, nidogens, and collagen IV inhibit the aggregation of Aβ and destabilize pre-formed fibrils of Aβ in vitro, while HSPG agrin and perlecan accelerate its aggregation (Aumailley and Krieg, 1996; Bronfman et al., 1996, 1998; Castillo et al., 1997; Cotman et al., 2000; Kiuchi et al., 2002a,b). Decreased amounts of collagen IV have been reported in small diameter vessels (<50 μm) from AD patients compared to aged-matched controls (Christov et al., 2008). Conversely, the levels of HSPGs were increased in AD brains (Berzin et al., 2000; Shimizu et al., 2009). Similar alterations have also been observed in the levels of collagen IV, laminin, nidogen 2, fibronectin, and perlecan in CAA-vulnerable brain regions of aged mice (Hawkes et al., 2013). These data suggest a change in the BM composition of the aged brain toward a pro-amyloidogenic environment. In addition, mice expressing the human ApoE ε4 allele show greater changes in CVBM expression over the lifecourse than mice expressing human Apo ε3 allele, in association with disrupted perivascular drainage of Aβ40 (Hawkes et al., 2012).

Relationship between parenchymal and vascular Aβ

Increased CAA severity has been noted in the brains of both mice and humans following anti-Aβ immunotherapy in association with decreased cerebral plaque load (Pfeifer et al., 2002b; Wilcock et al., 2004; Patton et al., 2006; Boche et al., 2008). These vascular Aβ deposits contained high levels of Aβ42, suggesting that following immunization, parenchymal Aβ became solubilized, drained along CVBMs, and became entrapped in the perivascular drainage pathways.

Collectively, these findings indicate that alterations in the composition, level of expression, or morphology of CVBMs may disturb perivascular drainage of Aβ from the parenchyma and initiate the deposition of Aβ within the walls of the cerebral vasculature, leading to a feed-forward mechanism of Aβ accumulation as CAA.

Conclusion

Increasing evidence supports a role for the cerebrovasculature in the development of AD. Preventative strategies targeting cardiovascular risk factors have been shown to be effective in reducing the incidence of AD (Guo et al., 1999; in’t Veld et al., 2001; Ohrui et al., 2004; Khachaturian et al., 2006; Haag et al., 2009a,b; Sink et al., 2009; Chuang et al., 2014), supporting the importance of maintaining cerebral vascular health across the lifespan in the prevention of disease. The CVBM plays an important role in cerebrovascular health, including mediating the clearance of Aβ. Therapeutic strategies targeted at improving and/or facilitating perivascular drainage of Aβ along the CVBM of the elderly brain may therefore represent a novel approach to the treatment of AD and CAA.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Age UK and the BBSRC for funding.

References

- Abbott N. J. (2004). Evidence for bulk flow of brain interstitial fluid: significance for physiology and pathology. Neurochem. Int. 45, 545–552 10.1016/j.neuint.2003.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alafuzoff I., Arzberger T., Al-Sarraj S., Bodi I., Bogdanovic N., Braak H., et al. (2008). Staging of neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer’s disease: a study of the BrainNet Europe Consortium. Brain Pathol. 18, 484–496 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00147.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aletrino M. A., Vogels O. J., Van Domburg P. H., Ten Donkelaar H. J. (1992). Cell loss in the nucleus raphes dorsalis in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 13, 461–468 10.1016/0197-4580(92)90073-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2014). Dementia Statistics. Available from: http://www.alz.co.uk/research/statistics

- Arbel-Ornath M., Hudry E., Eikermann-Haerter K., Hou S., Gregory J. L., Zhao L., et al. (2013). Interstitial fluid drainage is impaired in ischemic stroke and Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Acta Neuropathol. 126, 353–364 10.1007/s00401-013-1145-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumailley M., Bruckner-Tuderman L., Carter W. G., Deutzmann R., Edgar D., Ekblom P., et al. (2005). A simplified laminin nomenclature. Matrix Biol. 24, 326–332 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumailley M., Krieg T. (1996). Laminins: a family of diverse multifunctional molecules of basement membranes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 106, 209–214 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12340471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader B. L., Smyth N., Nedbal S., Miosge N., Baranowsky A., Mokkapati S., et al. (2005). Compound genetic ablation of nidogen 1 and 2 causes basement membrane defects and perinatal lethality in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 6846–6856 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6846-6856.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber A. J., Lieth E. (1997). Agrin accumulates in the brain microvascular basal lamina during development of the blood-brain barrier 23. Dev. Dyn. 208, 62–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barua N. U., Bienemann A. S., Hesketh S., Wyatt M. J., Castrique E., Love S., et al. (2012). Intrastriatal convection-enhanced delivery results in widespread perivascular distribution in a pre-clinical model. Fluids Barriers CNS 9, 2. 10.1186/2045-8118-9-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley D. J., Squires L. K., Zlokovic B. V., Mitrovic D. M., Hughes C. C., Revest P. A., et al. (1990). Permeability of the blood-brain barrier to the immunosuppressive cyclic peptide cyclosporin A. J. Neurochem. 55, 1222–1230 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb03128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell R. D., Winkler E. A., Sagare A. P., Singh I., LaRue B., Deane R., et al. (2010). Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging. Neuron 68, 409–427 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berzin T. M., Zipser B. D., Rafii M. S., Kuo-Leblanc V., Yancopoulos G. D., Glass D. J., et al. (2000). Agrin and microvascular damage in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 21, 349–355 10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00121-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird T. D., Miller B. L. (2007). Dementia, 17 Edn Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill [Google Scholar]

- Boche D., Zotova E., Weller R. O., Love S., Neal J. W., Pickering R. M., et al. (2008). Consequence of Abeta immunization on the vasculature of human Alzheimer’s disease brain. Brain 131(Pt 12), 3299–3310 10.1093/brain/awn261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondareff W., Mountjoy C. Q., Roth M. (1982). Loss of neurons of origin of the adrenergic projection to cerebral cortex (nucleus locus ceruleus) in senile dementia. Neurology 32, 164–168 10.1212/WNL.32.2.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Braak E. (1991). Neuropathological staging of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 82, 239–259 10.1007/BF00308809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Braak E., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K. (1986). Occurrence of neuropil threads in the senile human brain and in Alzheimer’s disease: a third location of paired helical filaments outside of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques. Neurosci. Lett. 65, 351–355 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90288-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfman F. C., Alvarez A., Morgan C., Inestrosa N. C. (1998). Laminin blocks the assembly of wild-type A beta and the Dutch variant peptide into Alzheimer’s fibrils. Amyloid 5, 16–23 10.3109/13506129809007285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfman F. C., Garrido J., Alvarez A., Morgan C., Inestrosa N. C. (1996). Laminin inhibits amyloid-beta-peptide fibrillation. Neurosci. Lett. 218, 201–203 10.1016/S0304-3940(96)13147-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger S., Noack M., Kirazov L. P., Kirazov E. P., Naydenov C. L., Kouznetsova E., et al. (2009). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) affects processing of amyloid precursor protein and beta-amyloidogenesis in brain slice cultures derived from transgenic Tg2576 mouse brain. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 27, 517–523 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2009.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns A. (1992). Psychiatric phenomena in dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int. Psychogeriatr. 4(Suppl. 1), 43–54 10.1017/S1041610292001145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffo M., Caruso G., Galatioto S., Meli F., Cacciola F., Germano A., et al. (2008). Immunohistochemical study of the extracellular matrix proteins laminin, fibronectin and type IV collagen in secretory meningiomas. J. Clin. Neurosci. 15, 806–811 10.1016/j.jocn.2007.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candiello J., Balasubramani M., Schreiber E. M., Cole G. J., Mayer U., Halfter W., et al. (2007). Biomechanical properties of native basement membranes. FEBS J. 274, 2897–2908 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05823.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carare R. O., Bernardes-Silva M., Newman T. A., Page A. M., Nicoll J. A., Perry V. H., et al. (2008). Solutes, but not cells, drain from the brain parenchyma along basement membranes of capillaries and arteries: significance for cerebral amyloid angiopathy and neuroimmunology. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 34, 131–144 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00926.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carare R. O., Hawkes C. A., Jeffrey M., Kalaria R. N., Weller R. O. (2013). Review: cerebral amyloid angiopathy, prion angiopathy, CADASIL and the spectrum of protein elimination failure angiopathies (PEFA) in neurodegenerative disease with a focus on therapy. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 39, 593–611 10.1111/nan.12042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson E. C., Brendel K., Hjelle J. T., Meezan E. (1978). Ultrastructural and biochemical analyses of isolated basement membranes from kidney glomeruli and tubules and brain and retinal microvessels. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 62, 26–53 10.1016/S0022-5320(78)80028-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castano E. M., Frangione B. (1988). Human amyloidosis, Alzheimer disease and related disorders. Lab. Invest. 58, 122–132 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo G. M., Ngo C., Cummings J., Wight T. N., Snow A. D. (1997). Perlecan binds to the beta-amyloid proteins (A beta) of Alzheimer’s disease, accelerates A beta fibril formation, and maintains A beta fibril stability. J. Neurochem. 69, 2452–2465 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69062452.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christov A., Ottman J., Hamdheydari L., Grammas P. (2008). Structural changes in Alzheimer’s disease brain microvessels. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 5, 392–395 10.2174/156720508785132334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang Y. F., Breitner J. C., Chiu Y. L., Khachaturian A., Hayden K., Corcoran C., et al. (2014). Use of diuretics is associated with reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease: the Cache County Study. Neurobiol. Aging. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Y. A., JH O., Kim J. Y., Kim K. J., Ahn K. J. (2009). Hypoperfusion and ischemia in cerebral amyloid angiopathy documented by 99mTc-ECD brain perfusion SPECT. J. Nucl. Med. 50, 1969–1974 10.2967/jnumed.109.062315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotman S. L., Halfter W., Cole G. J. (2000). Agrin binds to beta-amyloid (Abeta), accelerates abeta fibril formation, and is localized to Abeta deposits in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 15, 183–198 10.1006/mcne.1999.0816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cserr H. F., Cooper D. N., Suri P. K., Patlak C. S. (1981). Efflux of radiolabeled polyethylene glycols and albumin from rat brain. Am. J. Physiol. 240, F319–F328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl E. (1976). “Microscopic observations on cerebral arteries,” in The Cerebral Vessels Wall, eds Cervos-Navarro J., Betz E., Matakas F., Wüllenweber R. (New York: Raven Press; ), p. 15–21 [Google Scholar]

- Dickson D. W., Farlo J., Davies P., Crystal H., Fuld P., Yen S. H. (1988). Alzheimer’s disease. A double-labeling immunohistochemical study of senile plaques. Am. J. Pathol. 132, 86–101 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohgu S., Takata F., Yamauchi A., Nakagawa S., Egawa T., Naito M., et al. (2005). Brain pericytes contribute to the induction and up-regulation of blood-brain barrier functions through transforming growth factor-beta production 1. Brain Res. 1038, 208–215 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esiri M., Lee V. M.-Y., Trojanowski J. Q. (2004). The Neuropathology of Dementia, 2nd Edn Cambridge: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Farkas E., Luiten P. G. (2001). Cerebral microvascular pathology in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 64, 575–611 10.1016/S0301-0082(00)00068-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S., Hendrie H. C., Hall K. S., Hui S. (1998). The relationships between age, sex, and the incidence of dementia and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 55, 809–815 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannakopoulos P., Hof P. R., Michel J. P., Guimon J., Bouras C. (1997). Cerebral cortex pathology in aging and Alzheimer’s disease: a quantitative survey of large hospital-based geriatric and psychiatric cohorts. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 25, 217–245 10.1016/S0165-0173(97)00023-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbrunner R. H., Bernstein J. J., Tonn J. C. (1999). Cell-extracellular matrix interaction in glioma invasion. Acta Neurochir. 141, 295–305, discussion 4-5. 10.1007/s007010050301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Tung Y. C., Quinlan M., Wisniewski H. M., Binder L. I. (1986). Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 4913–4917 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z., Fratiglioni L., Zhu L., Fastbom J., Winblad B., Viitanen M. (1999). Occurrence and progression of dementia in a community population aged 75 years and older: relationship of antihypertensive medication use. Arch. Neurol. 56, 991–996 10.1001/archneur.56.8.991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag M. D., Hofman A., Koudstaal P. J., Breteler M. M., Stricker B. H. (2009a). Duration of antihypertensive drug use and risk of dementia: a prospective cohort study. Neurology 72, 1727–1734 10.1212/01.wnl.0000345062.86148.3f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag M. D., Hofman A., Koudstaal P. J., Stricker B. H., Breteler M. M. (2009b). Statins are associated with a reduced risk of Alzheimer disease regardless of lipophilicity. The Rotterdam Study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 80, 13–17 10.1136/jnnp.2008.150433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haan J., Hardy J. A., Roos R. A. (1991). Hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis – Dutch type: its importance for Alzheimer research. Trends Neurosci. 14, 231–234 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90120-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagg T., Muir D., Engvall E., Varon S., Manthorpe M. (1989). Laminin-like antigen in rat CNS neurons: distribution and changes upon brain injury and nerve growth factor treatment. Neuron 3, 721–732 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90241-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund M., Passant U., Sjobeck M., Ghebremedhin E., Englund E. (2006). Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cortical microinfarcts as putative substrates of vascular dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 21, 681–687 10.1002/gps.1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfter W., Candiello J., Hu H., Zhang P., Schreiber E., Balasubramani M. (2013). Protein composition and biomechanical properties of in vivo-derived basement membranes. Cell Adh. Migr. 7, 64–71 10.4161/cam.22479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallmann R., Horn N., Selg M., Wendler O., Pausch F., Sorokin L. M. (2005). Expression and function of laminins in the embryonic and mature vasculature. Physiol. Rev. 85, 979–1000 10.1152/physrev.00014.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes C. A., Gatherer M., Sharp M. M., Dorr A., Yuen H. M., Kalaria R., et al. (2013). Regional differences in the morphological and functional effects of aging on cerebral basement membranes and perivascular drainage of amyloid-beta from the mouse brain. Aging Cell 12, 224–236 10.1111/acel.12045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes C. A., Hartig W., Kacza J., Schliebs R., Weller R. O., Nicoll J. A., et al. (2011). Perivascular drainage of solutes is impaired in the ageing mouse brain and in the presence of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 121, 431–443 10.1007/s00401-011-0801-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes C. A., Sullivan P. M., Hands S., Weller R. O., Nicoll J. A., Carare R. O. (2012). Disruption of arterial perivascular drainage of amyloid-beta from the brains of mice expressing the human APOE epsilon4 allele. PLoS ONE 7:e41636. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzig M. C., Van Nostrand W. E., Jucker M. (2006). Mechanism of cerebral beta-amyloid angiopathy: murine and cellular models. Brain Pathol. 16, 40–54 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2006.tb00560.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzig M. C., Winkler D. T., Burgermeister P., Pfeifer M., Kohler E., Schmidt S. D., et al. (2004). Abeta is targeted to the vasculature in a mouse model of hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 954–960 10.1038/nn1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter D. D., Llinas R., Ard M., Merlie J. P., Sanes J. R. (1992). Expression of s-laminin and laminin in the developing rat central nervous system. J. Comp. Neurol. 323, 238–251 10.1002/cne.903230208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- in’t Veld B. A., Ruitenberg A., Hofman A., Stricker B. H., Breteler M. M. (2001). Antihypertensive drugs and incidence of dementia: the Rotterdam Study. Neurobiol. Aging 22, 407–412 10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00241-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal K., Liu F., Gong C. X., Grundke-Iqbal I. (2010). Tau in Alzheimer disease and related tauopathies. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 7, 656–664 10.2174/156720510793611592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinger K. A. (2002). Alzheimer disease and cerebrovascular pathology: an update. J. Neural Trans. 109, 813–836 10.1007/s007020200068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jucker M., Tian M., Ingram D. K. (1996a). Laminins in the adult and aged brain. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 28, 209–218 10.1007/BF02815224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jucker M., Tian M., Norton D. D., Sherman C., Kusiak J. W. (1996b). Laminin alpha 2 is a component of brain capillary basement membrane: reduced expression in dystrophic dy mice. Neuroscience 71, 1153–1161 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00496-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaria R. N. (1996). Cerebral vessels in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 72, 193–214 10.1016/S0163-7258(96)00116-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri R. (2003). Basement membranes: structure, assembly and role in tumour angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 422–433 10.1038/nrc1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khachaturian A. S., Zandi P. P., Lyketsos C. G., Hayden K. M., Skoog I., Norton M. C., et al. (2006). Antihypertensive medication use and incident Alzheimer disease: the Cache County Study. Arch. Neurol. 63, 686–692 10.1001/archneur.63.5.noc60013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshnoodi J., Pedchenko V., Hudson B. G. (2008). Mammalian collagen IV. Microsc. Res. Tech. 71, 357–370 10.1002/jemt.20564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiuchi Y., Isobe Y., Fukushima K., Kimura M. (2002a). Disassembly of amyloid beta-protein fibril by basement membrane components. Life Sci. 70, 2421–2431 10.1016/S0024-3205(02)01501-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiuchi Y., Isobe Y., Fukushima K. (2002b). Type IV collagen prevents amyloid beta-protein fibril formation. Life Sci. 70, 1555–1564 10.1016/S0024-3205(01)01528-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson E. B., Shadlen M. F., Wang L., McCormick W. C., Bowen J. D., Teri L., et al. (2004). Survival after initial diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 140, 501–509 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launer L. J., Ross G. W., Petrovitch H., Masaki K., Foley D., White L. R., et al. (2000). Midlife blood pressure and dementia: the Honolulu-Asia aging study. Neurobiol. Aging 21, 49–55 10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00096-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee K. K., Capizzi S., Yurchenco P. D. (2009). Scaffold-forming and adhesive contributions of synthetic laminin-binding proteins to basement membrane assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 8984–8994 10.1074/jbc.M809719200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao J., Xu F., Davis J., Otte-Holler I., Verbeek M. M., Van Nostrand W. E. (2005). Cerebral microvascular amyloid beta protein deposition induces vascular degeneration and neuroinflammation in transgenic mice expressing human vasculotropic mutant amyloid beta precursor protein. Am. J. Pathol. 167, 505–515 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62993-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner J. H. (1999). Renal basement membrane components. Kidney Int. 56, 2016–2024 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00785.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner J. H., Yurchenco P. D. (2004). Laminin functions in tissue morphogenesis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 255–284 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.094555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyakawa T., Shimoji A., Kuramoto R., Higuchi Y. (1982). The relationship between senile plaques and cerebral blood vessels in Alzheimer’s disease and senile dementia. Morphological mechanism of senile plaque production. Virchows Arch. B Cell Pathol. 40, 121–129 10.1007/BF02932857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natte R., Maat-Schieman M. L., Haan J., Bornebroek M., Roos R. A., van Duinen S. G. (2001). Dementia in hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis-Dutch type is associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy but is independent of plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Ann. Neurol. 50, 765–772 10.1002/ana.10040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan D. M., Hassell J. R. (1993). Perlecan, the large low-density proteoglycan of basement membranes: structure and variant forms. Kidney Int. 43, 53–60 10.1038/ki.1993.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohrui T., Matsui T., Yamaya M., Arai H., Ebihara S., Maruyama M., et al. (2004). Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in Japan. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 52, 649–650 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52178_7.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton R. L., Kalback W. M., Esh C. L., Kokjohn T. A., Van Vickle G. D., Luehrs D. C., et al. (2006). Amyloid-beta peptide remnants in AN-1792-immunized Alzheimer’s disease patients: a biochemical analysis. Am. J. Pathol. 169, 1048–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter L. S. (1994). Microvascular pathology and vascular basement membrane components in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 9, 33–40 10.1007/BF02816103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter L. S., Myers M. A., Barron E. (1994). Vascular basement membrane components and the lesions of Alzheimer’s disease: light and electron microscopic analyses. Microsc. Res. Tech. 28, 204–215 10.1002/jemt.1070280305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perris R. (1997). The extracellular matrix in neural crest-cell migration. Trends Neurosci. 20, 23–31 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10063-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer L. A., White L. R., Ross G. W., Petrovitch H., Launer L. J. (2002a). Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cognitive function: the HAAS autopsy study. Neurology 58, 1629–1634 10.1212/WNL.58.11.1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer M., Boncristiano S., Bondolfi L., Stalder A., Deller T., Staufenbiel M., et al. (2002b). Cerebral hemorrhage after passive anti-Abeta immunotherapy. Science 298, 1379. 10.1126/science.1078259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasi K., Hurskainen M., Kallio M., Staven S., Sormunen R., Heape A. M., et al. (2010). Lack of collagen XV impairs peripheral nerve maturation and, when combined with laminin-411 deficiency, leads to basement membrane abnormalities and sensorimotor dysfunction. J. Neurosci. 30, 14490–14501 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2644-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roher A. E., Kuo Y. M., Esh C., Knebel C., Weiss N., Kalback W., et al. (2003). Cortical and leptomeningeal cerebrovascular amyloid and white matter pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Med. 9, 112–122 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schley D., Carare-Nnadi R., Please C. P., Perry V. H., Weller R. O. (2006). Mechanisms to explain the reverse perivascular transport of solutes out of the brain. J. Theor. Biol. 238, 962–974 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz W. (1938). Studien zur pathologie der Hirgefässe. II. Die drusige entartung der Hirnarterien und capillaren. Z. Ges. Neurol. Psychiatr. 162, 694–715 10.1007/BF02890989 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shah N. S., Vidal J. S., Masaki K., Petrovitch H., Ross G. W., Tilley C., et al. (2012). Midlife blood pressure, plasma beta-amyloid, and the risk for Alzheimer disease: the Honolulu Asia Aging Study. Hypertension 59, 780–786 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.178962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu H., Ghazizadeh M., Sato S., Oguro T., Kawanami O. (2009). Interaction between beta-amyloid protein and heparan sulfate proteoglycans from the cerebral capillary basement membrane in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Clin. Neurosci. 16, 277–282 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H. K., Jones P. B., Garcia-Alloza M., Borrelli L., Greenberg S. M., Bacskai B. J., et al. (2007). Age-dependent cerebrovascular dysfunction in a transgenic mouse model of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain 130(Pt 9), 2310–2319 10.1093/brain/awm156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sink K. M., Leng X., Williamson J., Kritchevsky S. B., Yaffe K., Kuller L., et al. (2009). Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and cognitive decline in older adults with hypertension: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 169, 1195–1202 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sixt M., Engelhardt B., Pausch F., Hallmann R., Wendler O., Sorokin L. M. (2001). Endothelial cell laminin isoforms, laminins 8 and 10, play decisive roles in T cell recruitment across the blood-brain barrier in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Cell Biol. 153, 933–946 10.1083/jcb.153.5.933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin L. (2010). The impact of the extracellular matrix on inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 712–723 10.1038/nri2852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N., Iwatsubo T., Odaka A., Ishibashi Y., Kitada C., Ihara Y. (1994). High tissue content of soluble beta 1-40 is linked to cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Am J Pathol 145(2):452–460 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szentistvanyi I., Patlak C. S., Ellis R. A., Cserr H. F. (1984). Drainage of interstitial fluid from different regions of rat brain. Am. J. Physiol. 246(6 Pt 2), F835–F844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzi R. E. (2012). The genetics of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, a006296. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeling J. L., Carare R. O., Glennie M. J., Perry V. H. (2012). Intracerebral immune complex formation induces inflammation in the brain that depends on Fc receptor interaction. Acta Neuropathol. 124, 479–490 10.1007/s00401-012-0995-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyboll J., Kortesmaa J., Cao R., Soininen R., Wang L., Iivanainen A., et al. (2002). Deletion of the laminin alpha4 chain leads to impaired microvessel maturation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1194–1202 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1194-1202.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J., Shi J., Smallman R., Iwatsubo T., Mann D. M. (2006). Relationships in Alzheimer’s disease between the extent of Abeta deposition in cerebral blood vessel walls, as cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and the amount of cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells and collagen. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 32, 332–340 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2006.00732.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpl R. (1996). Macromolecular organization of basement membranes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 8, 618–624 10.1016/S0955-0674(96)80102-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpl R., Brown J. C. (1996). Supramolecular assembly of basement membranes. Bioessays 18, 123–132 10.1002/bies.950180208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinters H. V. (1987). Cerebral amyloid angiopathy. A critical review. Stroke 18, 311–324 10.1161/01.STR.18.2.311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinters H. V., Wang Z. Z., Secor D. L. (1996). Brain parenchymal and microvascular amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 6, 179–195 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00799.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogels O. J., Broere C. A., ter Laak H. J., ten Donkelaar H. J., Nieuwenhuys R., Schulte B. P. (1990). Cell loss and shrinkage in the nucleus basalis Meynert complex in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 11, 3–13 10.1016/0197-4580(90)90056-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Olbricht W. L. (2011). Fluid mechanics in the perivascular space. J. Theor. Biol. 274, 52–57 10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber M. (1992). Basement membrane proteins. Kidney Int. 41, 620–628 10.1038/ki.1992.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller R. O., Massey A., Newman T. A., Hutchings M., Kuo Y. M., Roher A. E. (1998). Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: amyloid beta accumulates in putative interstitial fluid drainage pathways in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Pathol. 153, 725–733 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65616-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller R. O., Subash M., Preston S. D., Mazanti I., Carare R. O. (2008). Perivascular drainage of amyloid-beta peptides from the brain and its failure in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 18, 253–266 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00133.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse P. J., Price D. L., Struble R. G., Clark A. W., Coyle J. T., Delon M. R. (1982). Alzheimer’s disease and senile dementia: loss of neurons in the basal forebrain. Science 215, 1237–1239 10.1126/science.7058341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcock D. M., Rojiani A., Rosenthal A., Subbarao S., Freeman M. J., Gordon M. N., et al. (2004). Passive immunotherapy against Abeta in aged APP-transgenic mice reverses cognitive deficits and depletes parenchymal amyloid deposits in spite of increased vascular amyloid and microhemorrhage. J. Neuroinflammation 1, 24. 10.1186/1742-2094-1-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski H. M., Wegiel J. (1994). Beta-amyloid formation by myocytes of leptomeningeal vessels. Acta Neuropathol. 87, 233–241 10.1007/BF00296738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski H. M., Wegiel J., Kotula L. (1996). Review. David Oppenheimer Memorial Lecture 1995: some neuropathological aspects of Alzheimer’s disease and its relevance to other disciplines. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 22, 3–11 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1996.tb00839.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C., Ivars F., Anderson P., Hallmann R., Vestweber D., Nilsson P., et al. (2009). Endothelial basement membrane laminin alpha5 selectively inhibits T lymphocyte extravasation into the brain. Nat. Med. 15, 519–527 10.1038/nm.1957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T., Lin C., Sanan D. A., Mucke L., Masliah E. (2000). Chronic overproduction of transforming growth factor-beta1 by astrocytes promotes Alzheimer’s disease-like microvascular degeneration in transgenic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 156, 139–150 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64713-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousif L. F., Di Russo J., Sorokin L. (2013). Laminin isoforms in endothelial and perivascular basement membranes. Cell Adh. Migr. 7, 101–110 10.4161/cam.22680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurchenco P. D., Schittny J. C. (1990). Molecular architecture of basement membranes. FASEB J. 4, 1577–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarow C., Barron E., Chui H. C., Perlmutter L. S. (1997). Vascular basement membrane pathology and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 826, 147–160 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang E. T., Richards H. K., Kida S., Weller R. O. (1992). Directional and compartmentalised drainage of interstitial fluid and cerebros- pinal fluid from the rat brain. Acta Neuropathol. 83, 233–239 10.1007/BF00296784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlokovic B. V. (2008). The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron 57, 178–201 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]