Abstract

Background:

A few reports demonstrate the comorbidity of food allergy and allergic march in adult patients.

Aims and Objectives:

To evaluate, if there is some relation in atopic dermatitis patients at the age 14 years and older who suffer from food allergy to common food allergens to other allergic diseases and parameters as bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, duration of atopic dermatitis, family history and onset of atopic dermatitis.

Materials and Methods:

Complete dermatological and allergological examination was performed; these parameters were examined: food allergy (to wheat flour, cow milk, egg, peanuts and soy), the occurrence of bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, duration of atopic dermatitis, family history and onset of atopic dermatitis. The statistical evaluation of the relations among individual parameters monitored was performed.

Results:

Food allergy was altogether confirmed in 65 patients (29%) and these patients suffer significantly more often from bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis. Persistent atopic dermatitis lesions and positive data in family history about atopy are recorded significantly more often in patients with confirmed food allergy to examined foods as well. On the other hand, the onset of atopic dermatitis under 5 year of age is not recorded significantly more often in patients suffering from allergy to examined foods.

Conclusion:

Atopic dermatitis patients suffering from food allergy suffer significantly more often from allergic rhinitis, bronchial asthma, persistent eczematous lesions and have positive data about atopy in their family history.

Keywords: Bronchial asthma, atopic dermatitis, family history, food allergy, onset of atopic dermatitis, persistent eczematous lesions, allergic rhinitis

What was known?

Allergic march refers to a subset of allergic disorders that commonly begin in early childhood, such as food allergies, bronchial asthma, allergic allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis. Approximately one-third of children with severe atopic dermatitis were reported to suffer from IgE-mediated food allergy as well. There is a lack of reports focusing on long-term studies of the clinical and allergometric evaluations observed during the course of atopic dermatitis in respect to its evolution and association with allergic responses in affected patients.

Introduction

Increase in allergic diseases, including atopic dermatitis, bronchial asthma and allergic allergic rhinitis over the last 30-40 years has been well documented worldwide.[1] Allergic diseases are also an important public health problem because they significantly increase socioeconomic burden by lowering the quality of life and work productivity of affected patients and their families.[2,3,4] However, a few reports demonstrate the comorbidity of food allergy and allergic march in adults. Approximately one-third of children with severe atopic dermatitis were reported to suffer from IgE-mediated food allergy as well.[5,6] In addition, food allergy that developed at a young age increased the risk for atopic dermatitis, bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis at 8 years of age,[7] in 9-11-year-old children food allergy was highly associated with bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis.[8] Two prospective studies show that cow's milk allergy is associated with subsequent development of either bronchial asthma or allergic allergic rhinitis.[9,10] There is a lack of reports focusing on long-term studies of the clinical and allergometric evaluations observed during the course of atopic dermatitis in respect to its evolution and association with allergic responses in affected patients.

Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to evaluate, if there is some relation in atopic dermatitis patients aged 14 years and older who suffer from food allergy to common food allergens (wheat flour, cow milk, egg, peanuts and soy) to other allergic diseases and parameters as bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, duration of atopic dermatitis, family history and onset of atopic dermatitis.

Materials and Methods

In the period from January 2005 to May 2012, 224 patients suffering from atopic dermatitis aged 14 years and older were examined. Complete dermatological and allergological examination was performed at the Department of Dermatology and Venereology Faculty Hospital and Medical Faculty of Charles University, Hradec Králové, Czech Republic. These parameters were examined: food allergy (to wheat flour, cow milk, egg, peanuts and soy), bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, duration of atopic dermatitis, family history and onset of atopic dermatitis. The statistical evaluation of the relations among individual parameters monitored was performed; it was evaluated, if there is some relation in patients, who suffer from food allergy to the occurrence of bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, to the duration of atopic dermatitis lesions (persistent or occasionally), occurrence of positive family history about atopy and the onset of atopic dermatitis.

This study was approved by Ethics committee. There is no conflict of interest. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials and Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines were followed.[11] This study was supported by financial support from Charles University.

Evaluation of parameters monitored

The diagnosis of food allergy was made according to the results of specific IgE (sIgE), skin prick tests (SPT), atopy patch test (APT) and open exposure tests. Patients with a positive result in the open exposure test (early and/or late reactions) with the examined food and with a positive result at least in one of the diagnostic methods (sIgE, APT, SPT) to this food were considered as the patients with food allergy. Patients with an early reaction after the ingestion of examined food repeatedly in their history from their childhood were considered as patients with food allergy also; the open exposure test was not performed in these patients because of risk of anaphylactic reaction. Sensitisation to examined food was confirmed in patients with the negative results in the open exposure test, but with the positive results in sIgE and/or SPT and/or APT.

The diagnosis of bronchial asthma was made according to the results of spirometry at allergological outpatients department.

The evaluation of rhinitis (seasonal or perennial) was made according to the anamnestical data.

The evaluation of duration of atopic dermatitis-was made as persistent or occasionally according to the dermatologist examination during one last year and according to the patients information.

The onset of atopic dermatitis was evaluated according to the patients history.

The family history was evaluated according to the patients information (the occurrence of allergy, atopic dermatitis, asthma bronchiale, rhinoconjunctivitis in parents, brothers, sisters, children).

Statistical analysis

The evaluation, if there is some association in patients who suffer from food allergy to common food allergens (wheat flour, cow milk, egg, peanuts and soy) to other allergic diseases and parameters as bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, duration of atopic dermatitis, family history, and onset of atopic dermatitis. Pairs of these categories were entered in contingency tables and the Chi-square test for independence of these variables was performed with the level of significance set to 5%. The results were processed in the Department of Medical Biophysics of Medical Faculty of Charles University in Hradec Králové.

Results

Altogether 224 persons suffering from atopic dermatitis were included in the study: 70 men and 154 women entered the study with the average age 26.4 years (s.d. 9.1 years), min. 14 max. 63 years; with the median SCORAD[12] 13.3 ± 13.1 (range 79.5-12.5) at the beginning of the study.

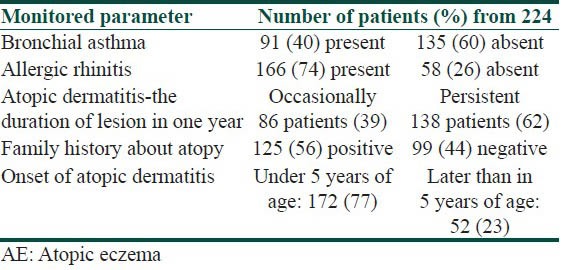

Table 1 indicates the occurrence of the parameters observed in patients with atopic dermatitis-the number of patients suffering from bronchial asthma and from allergic rhinitis, the number of patients with persistent or occasional lesions of atopic dermatitis, the data about atopy in family history, the number of patients with the onset of atopic dermatitis under 5 years of age. From 224 patients, 91 suffer from bronchial asthma and 166 patients suffer from allergic rhinitis. Persistent lesions of atopic dermatitis in one last year were recorded in 138 patients, only occasionally lesions were recorded in 86 patients. Positive findings about atopy in family history were recorded in 125 patients, no data about atopy in family history were recorded in 99 patients. The onset of atopic dermatitis under 5 years of age was recorded in 172 patients, later onset of atopic dermatitis was recorded in 52 patients.

Table 1.

Occurrence of monitored parameters in percents in patients with AE (from 224 patients)

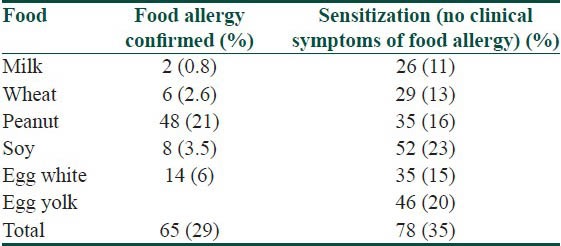

The number of patients with food allergy and food sensitisation is recorded in Table 2. Food allergy was altogether confirmed in 65 patients (29%); from these patients 54 patients suffer from allergy to one food, 11 patients allergy to two and more foods The food allergy was confirmed to milk in 2 patients (0.8%) to wheat flour in 6 patients (2.6%), to peanuts in 48 patients (21%), to soy in 8 patients (3.5%) and to egg in 14 patients (6%). Sensitisation was altogether confirmed in 78 patients (35%), 36 patients are sensitised to one food, 42 patients were sensitised to two or to more foods. Sensitisation to milk was confirmed in 26 patients (11%), to wheat flour in 29 patients (13%), to peanuts in 35 patients (16%), to soy in 52 patients (23%) and to egg in 46 patients (20%).

Table 2.

Number of patients with confirmed food allergy and with sensitisation to examined foods from 224 patients included in the study

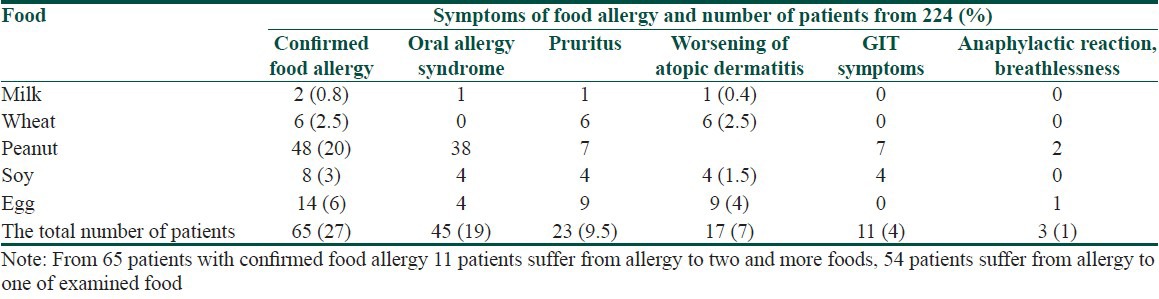

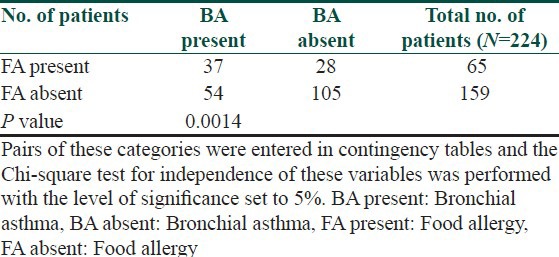

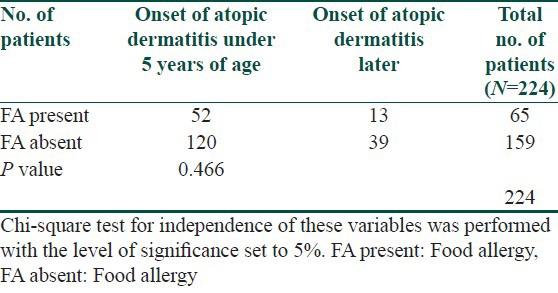

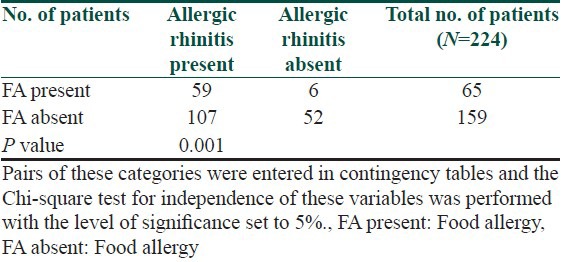

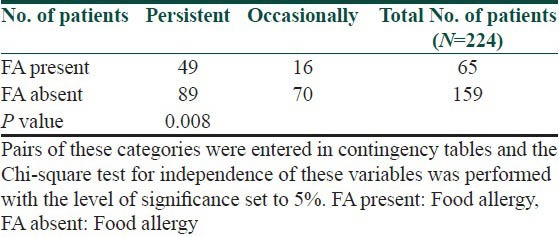

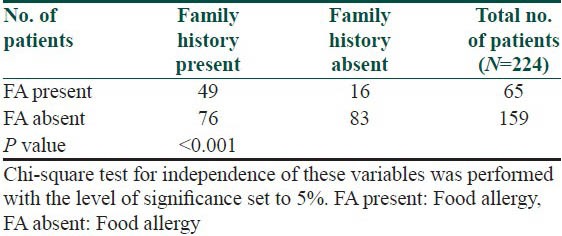

The symptoms of food allergy are recorded in Table 3. The sequence of recorded symptoms of food allergy is: oral allergy syndrome in 45 patients (19%), pruritus in 23 patients (9.5%), worsening of atopic dermatitis in 17 patients (7%), gastrointestinal problems as abdominal pain and cramps in 11 patients (5%) and anaphylactic reaction after egg and peanuts in 3 patients (1%). The results of the occurrence in follow-up categories and their statistical analysis are summarized in Tables 4–8. The occurrence of bronchial asthma in patients suffering from allergy and in patients without allergy to examined foods is recorded in Table 4. Data shows a statistically significant relation; patients suffering from allergy to examined food suffer significantly more often from bronchial asthma. The occurrence of allergic rhinitis in patients suffering from allergy and in patients without allergy to examined foods is recorded in Table 5. Data show the statistically significant relation; patients suffering from allergy to examined food suffered significantly more often from allergic rhinitis. The occurrence of persistent or occasionally lesions of atopic dermatitis in last year in patients suffering from allergy and in patients without allergy to examined foods is recorded in Table 6. Data show a statistically significant relation; patients suffering from allergy to examined food suffer significantly more often from persistent lesions of atopic dermatitis. The evaluation of family history in patients suffering from allergy and in patients without allergy to examined foods is recorded in Table 7. Data show a statistically significant relation; the occuremce of atopy in family history is recorded significanrly more often in patients suffering from allergy to examined foods. The evaluation of onset of atopic dermatitis in patients suffering from allergy and in patients without allergy to examined foods is recorded in Table 8. Data show no statistically significant relation; the onset of atopic dermatitis under 5 years of age is not recorded significantly more often in patients suffering from allergy to examined food than in patients without food allergy.

Table 3.

Symptoms of food allergy

Table 4.

Occurrence of bronchial asthma in patients suffering from allergy and in patients without allergy to examined foods in %

Table 8.

Evaluation of onset of atopic dermatitis in patients suffering from allergy and in patients without allergy to examined foods

Table 5.

Occurrence of allergic rhinitis in patients suffering from allergy and in patients without allergy to examined foods

Table 6.

Occurrence of persistent or occasionally atopic dermatitis in patients suffering from allergy and in patients without allergy to examined foods

Table 7.

Evaluation of family history in patients suffering from allergy and in patients without allergy to examined foods

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate, if there is some relation in atopic dermatitis patients who suffer from food allergy to common food allergens (wheat flour, cow milk, egg, peanuts and soy) to other allergic diseases and parameters as bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, duration of atopic dermatitis, family history and onset of atopic dermatitis. Many studies demonstrate the prevalence of allergic diseases; however, most analyzed a limited period from infancy to later childhood and/or to early adolescence. Allergic march refers to a subset of allergic disorders that commonly begin in early childhood, such as food allergies, bronchial asthma, allergic allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis. Patients diagnosed with a certain allergic disease have a greater likelihood of developing other allergic diseases. The sequence of foods responsible for food allergy at our study with recorded early and/or late allergic reactions is: peanuts in 48 patients (20%), egg in 14 patients (6%), soy in 8 patients (3%), wheat in 6 patients (2.6%) and milk in 2 patients (0.8%). According to our results, patients suffering from atopic dermatitis and allergy to one or more of examined foods suffer significantly more often from bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis. Persistent atopic dermatitis lesions and positive data in family history about atopy are recorded significantly more often in patients with confirmed food allergy to examined foods as well. On the other hand, the onset of atopic dermatitis under 5 years of age is not in correlation to allergy to examined foods; the onset of atopic dermatitis under 5 year of age is not recorded significantly more often in patients suffering from allergy to examined food in comparison to patients without allergy to examined foods. Recent modern theories suggest that the most important factor that precipitates allergic march is an impaired epidermal barrier. There is a clear evidence of a relationship between filaggrin gene (FLG) mutations and atopic dermatitis. FLG also increased the risk for bronchial asthma with atopic dermatitis and the risk for allergic allergic rhinitis with/without atopic dermatitis.[13] Moreover, the presence of an FLG mutation in infants with early onset food sensitization and atopic dermatitis increases the risk for bronchial asthma.[14,15] In adult patients with atopic dermatitis, studies investigating the co-prevalence of atopic dermatitis and food allergy are still scarce and exact data are not available.[16,17] The results of a population-based study in Germany involving 1,739 unselected patients who had completed questionnaires confirmed that food allergy in adult atopic dermatitis patients is rare.[18] We have confirmed that in atopic dermatitis patients who suffer from food allergy is greater likelihood of developing other allergic diseases, but we have not confirmed that there is the relation to the onset of atopic dermatitis. The explanation of this result may be the fact, that allergy only to basic foods was examined and that the other kinds of food allergy were not evaluated at our study; other explanation may be, that we examined adolescent and adults suffering from atopic dermatitis. In sensitised infants to three years of age with atopic dermatitis, food, such as cow milk or hen's egg, can directly cause flares of atopic dermatitis, but 80% of them outgrow their food allergy. According to some studies, early onset of atopic dermatitis was found to be associated with high-risk IgE levels in food sensitization; many epidemiological investigations have suggested that food allergy is a risk factor for the appearance of other allergic disease in later childhood.[7,19,20,21,22,23] In another study dealing with atopic march[24] was suggested that atopic dermatitis co-morbid with food allergyin early childhood plays an important role in subsequent development of allergic march. Early childhood is thought to be a key period for the prevention of allergic march, and adolescence is another key period for the prevention of recurrence. The prevention of recurrence would decrease allergic disease in adulthood. Further prospective studies using large cohorts are necessary to assess this issue.[24] Furthermore, Ricci et al., reported that the integrated management of atopic dermatitis decreases the likelihood that affected children would progress toward respiratory allergic disease.[25] Thus, prompt management of atopic dermatitis and food allergy that develop in early infancy may be a successful method for preventing allergic march. According to summary of key findings from 24 systematic reviews of atopic dermatitis about the primary prevention of atopic dermatitis, epidemiological evidence points to the protective effects of early daycare, endotoxin exposure, consumption of unpasteurized milk, and early exposure to dogs, but antibiotic use in early life may increase the risk for atopic dermatitis. With regard to prevention of atopic dermatitis, there is currently no strong evidence of benefit for exclusive breastfeeding, hydrolysed protein formulas, soy formulas, maternal antigen avoidance, omega-3 or omega-6 fatty-acid supplementation, or use of prebiotics or probiotics.[26]

Various studies evaluating the course of atopic dermatitis were performed in India too, authors as Dhar, Kanwar, Sarkar and Sarasvat performed studies dealing with prevalence of atopic dermatitis, personal and family history, with the occurrence of bronchial asthma and with the degree of growth retardation. Although the prevalence of atopic dermatitis is considered to be increasing, it still remains low in India in comparison to developed countries. Clinical manifestations largely remain the same, though the relevance of minor features of Hanifin and Rajka's criteria for diagnosis of atopic dermatitis has been questioned in some Indian studies. This may be due to differences in the clinical manifestation, or generally milder disease severity in Indian patients.[27] Personal and family history of atopy in children with atopic dermatitis in North India was evaluated in Dhar et al. study. Personal and/or family history are evaluated in 130 children, 83 boys and 47 girls, with atopic dermatitis in the age group of 3 months to 1.5 years, with mean age 2.2 + 1.93 years at onset of atopic dermatitis. The data have been compared with those obtained from 130 age and sex matched controls.[28] Both atopic dermatitis and bronchial asthma has been known to cause retarded growth. In India, the degree of growth retardation in atopic dermatitis patients has been correlated with extensive eczema, more potent topical corticosteroid use, and more severe coexisting asthma. In a study of 108 children with ‘pure atopic dermatitis’ (atopic dermatitis without associated bronchial asthma) between 1 and 5 years of age, 54% weighed below 10th percentile while height of 28% were below 10th percentile according to National Center for Health Statistics standards.[29,30] In India, various epidemiologic factors and clinical patterns of the same were evaluated in 125 patients out of 418 attending the pediatric dermatology clinic over a period of 11/2 years. Of these, 26 were infants (upto 1 year of age) and 99 were children. Mean duration of the disease in the infantile group was 3 months while in the childhood group it was 6 years. In the infantile group, family history of atopy was found in 11 patients (42.3%), while in the childhood group 35 (35.35%) had family history of atopy, 7 (7.07%) had personal history of atopy and 2 (2.02%) had both personal and family history of atopy. The infantile group had more frequent facial involvement and acute type of eczema, while in the childhood type, site involvement was less specific and chronic type of eczema was more frequent. Most of the patients had mild to moderate degree of severity of the disease.[31]

Conclusion

The occurrence of bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis is recorded more often in in adolescent and adults atopic dermatitis patients who suffer from food allergy; these patients also suffer more often from persistent eczematous lesions and have positive data about atopy in their family history.

What is new?

Atopic dermatitis patients suffering from food allergy suffer significantly more often from allergic rhinitis, bronchial asthma, persistent eczematous lesions and have positive data about atopy in their family history.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368:733–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murota H, Kitaba S, Tani M, Wataya-Kaneda M, Azukizawa H, Tanemura A, et al. Impact of sedative and non-sedative antihistamines on the impaired productivity and quality of life in patients with pruritic skin diseases. Allergol Int. 2010;59:345–54. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.10-OA-0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murota H, Kitaba S, Tani M, Wataya-Kaneda M, Katayama I. Effects of nonsedative antihistamines on productivity of patients with pruritic skin diseases. Allergy. 2010;65:929–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suh DC, Sung J, Gause D, Raut M, Huang J, Choi IS. Economic burden of atopic manifestations in patients with atopic dermatitis-analysis of administrative claims. J Manag Care Pharm. 2007;13:778–89. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2007.13.9.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werfel T, Ballmer-Weber B, Eigenmann PA, Niggemann B, Rancé F, Turjanmaa K, et al. Eczematous reactions to food in atopic eczema: position paper of the EAACI and GA2LEN. Allergy. 2007;62:723–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hauk PJ. The role of food allergy in atopic dermatitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2008;8:188–94. doi: 10.1007/s11882-008-0032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostblom E, Lilja G, Pershagen G, van Hage M, Wickman M. Phenotypes of food hypersensitivity and development of allergic diseases during the first 8 years of life. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:1325–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pénard-Morand C, Raherison C, Kopferschmitt C, Caillaud D, Lavaud F, Charpin D, et al. Prevalence of food allergy and its relationship to asthma and allergic allergic rhinitis in schoolchildren. Allergy. 2005;60:1165–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Host A, Halken S. A prospective study of cow milk allergy in Danish infants during the first 3 years of life. Clinical course in relation to clinical and immunological type of hypersensitivity reaction. Allergy. 1990;45:587–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1990.tb00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Host A, Halken S, Jacobsen HP, Christensen AE, Herskind AM, Plesner K. Clinical course of cow's milk protein allergy/intolerance and atopic diseases in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;(13 Suppl 15):S23–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3038.13.s.15.7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. for the CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trial. BMJ. 2010;340:869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: The SCORAD Index (consensus report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis) Dermatology. 1993;186:23–31. doi: 10.1159/000247298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van den Oord RA, Sheikh A. Filaggrin gene defects and risk of developing allergic sensitisation and allergic disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b2433. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marenholz I, Kerscher T, Bauerfeind A, Esparza-Gordillo J, Nickel R, Keil T, et al. An interaction between filaggrin mutations and early food sensitization improves the prediction of childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:911–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filipiak-Pittroff B, Schnopp C, Berdel D, Naumann A, Sedlmeier S, Onken A, et al. GINIplus and LISAplus study groups. Predictive value of food sensitization and filaggrin mutations in children with eczema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.014. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werfel T, Breuer K. Role of food allergy in atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4:379–85. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200410000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heratizadeh A, Wichmann K, Werfel T. Food allergy and atopic dermatitis: How are they connected? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:284–91. doi: 10.1007/s11882-011-0202-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Worm M, Forschner K, Lee HH, Roehr CC, Edenharter G, Niggemann B, et al. Frequency of atopic dermatitis and relevance of food allergy in adults in Germany. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:119–2. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Punekar YS, Sheikh A. Establishing the sequential progression of multiple allergic diagnoses in a UK birth cohort using the General Practice Research Database. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:1889–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Hammadi S, Zoubeidi T, Al-Maskari F. Predictors of childhood food allergy: Significance and implications. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2011;29:313–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill DJ, Hosking CS, de Benedictis FM, Oranje AP, Diepgen TL, Bauchau V. Confirmation of the association between high levels of immunoglobulin E food sensitization and eczema in infancy: An international study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:161–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novembre E, Cianferoni A, Lombardi E, Bernardini R, Pucci N, Vierucci A. Natural history of “intrinsic” atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2001;56:452–3. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.056005452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wuthrich B, Schmid-Grendelmeier P. Natural course of AEDS. Allergy. 2002;57:267–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.1n3572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kijima A, Murota H, Takahashi A, Arase N, Yang L, Nishioka M, et al. Prevalence and Impact of Past History of Food Allergy in Atopic Dermatitis. Allergol Int. 2013;62:105–12. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.12-OA-0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricci G, Patrizi A, Giannetti A, Dondi A, Bendandi B, Masi M. Does improvement management of atopic dermatitis influence the appearance of respiratory allergic diseases? A follow-up study. Clin Mol Allergy. 2010;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1476-7961-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torley D, Futamura M, Williams HC, Thomas KS. What's new in atopic eczema? An analysis of systematic reviews published in 2010-1. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:449–56. doi: 10.1111/ced.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanwar AJ, De D. Epidemiology and clinical features of atopic dermatitis in India. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:471–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.87112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhar S, Kanwar AJ. Personal and family history of atopy in children with atopic dermatitis in north India. Indian J Dermatol. 1997;42:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dhar S, Mondal B, Malakar R, Ghosh A, Gupta AB. Correlation of the severity of atopic dermatitis with growth retardation in pediatric age group. Indian J Dermatol. 2005;50:125–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saraswat A, Handa S, Bhalla AK, Kumar B. Growth pattern in ‘pure’ atopic dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol. 2002;47:205–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarkar R, Kanwar AJ. Clinico-Epidemiological profile and factors affecting severity of atopic dermatitis in north Indian children. Indian J Dermatol. 2004;49:117–22. [Google Scholar]