Abstract

Pneumothorax is a frequent cause of admission in an emergency department. It can be due to a leakage of air from an air-filled lung cavitation into the pleural space. We report the unusual case of pneumothorax in a patient with a pulmonary cavitary infectious process mimicking tuberculosis. A 30-year-old asthmatic man, treated for several years with low-dose inhaled corticosteroids, presented a complete left tension pneumothorax and chronic necrotising pulmonary aspergillosis that mimicked initial pulmonary tuberculosis. Antifungal treatment by voriconazole was started and continued for 1 year, with a favourable outcome. This case highlights that chronic necrotising pulmonary aspergillosis is a diagnosis that should be considered in patients with a clinical presentation of pulmonary tuberculosis or in patients experiencing pneumothorax, especially in the context of corticosteroid treatment.

Background

Pneumothorax is a frequent cause of admission in an emergency department. There are many aetiologies, some benign and others life-threatening. Pneumothorax can be due to a leakage of air from an air-filled lung cavitation into the pleural space. This case highlights that emergency physicians should be aware that chronic necrotising pulmonary aspergillosis (CNPA) is a diagnosis that should be considered in patients experiencing pneumothorax and presenting a pulmonary cavitary infectious process that mimicks pulmonary tuberculosis.

Case presentation

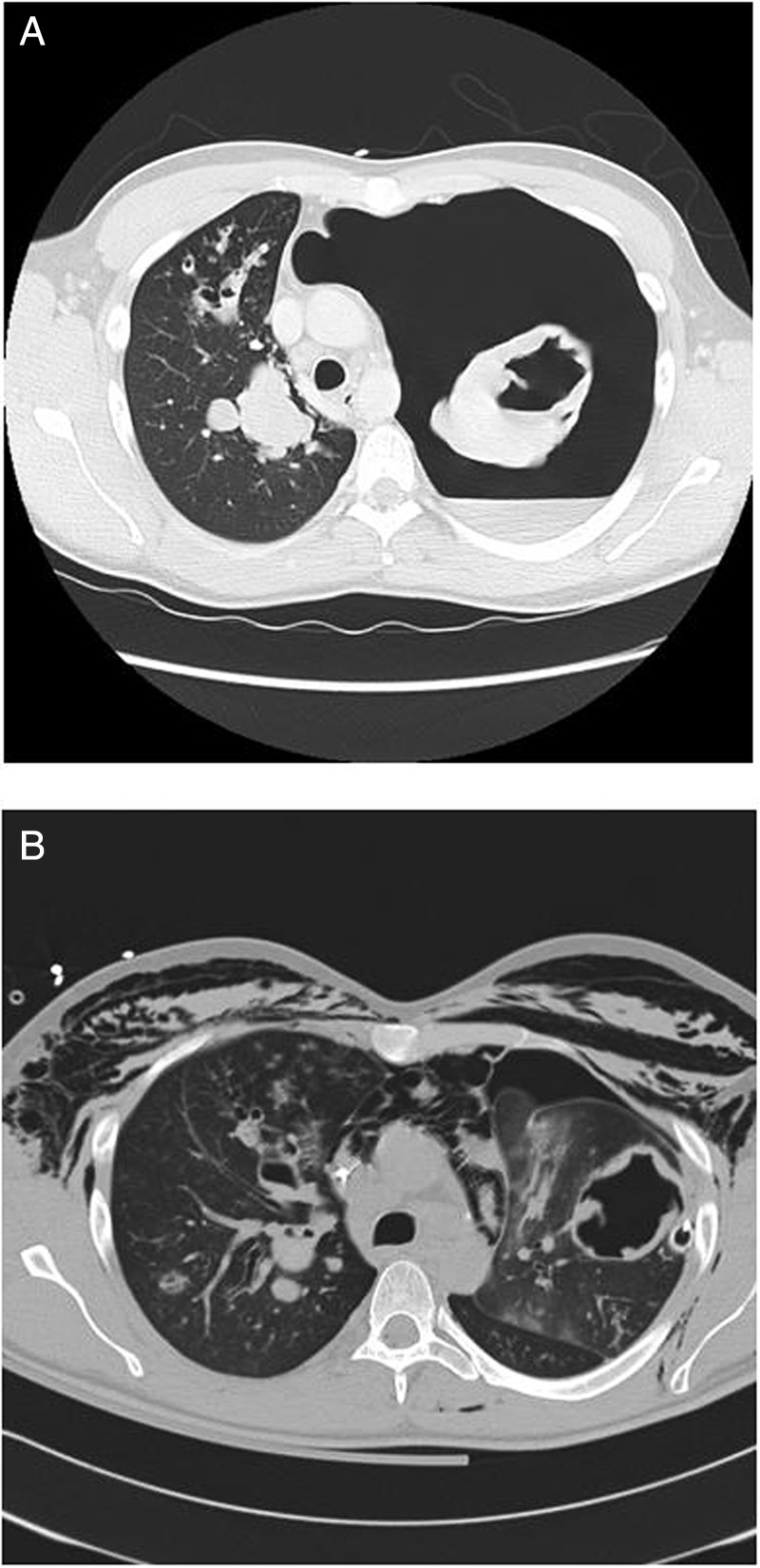

A 30-year-old man with childhood asthma, who had been treated for several years with low-dose inhaled corticosteroids, came to our emergency department (day 0) with a chronic productive cough, acute left chest pain associated with moderate dyspnoea, fever and weight loss. The history included frequent travels to Rwanda (Africa). However, he did not have any history of tuberculosis. The chest CT scan revealed a complete left tension pneumothorax associated with voluminous cavitary lesions in the left lung and parenchymal infiltrates in the right lung (figure 1A). A left chest drain was inserted and continuous low negative pressure drainage of the pleural space was started. Based on a high clinical and radiological suspicion of pulmonary tuberculosis, a quadri-antituberculosis therapy was initiated. Another chest CT scan (day 7) revealed bilateral nodular opacities and cystic bronchiectasis with mucoid impactions, and persistent voluminous cavitations in the left lung (figure 1B). Owing to an intense bubbling in the underwater seal, a thoracotomy was performed at day 10, with resection of a bronchopleural fistula, left pleural decortication and lung biopsies. The diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis was definitely eliminated following multiple negative mycobacterial cultures (bronchial and pleural samples) and by the absence of granuloma with caseation on lung biopsies. In addition, the PCR results for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the bronchoalveolar lavage, as well as the tuberculin test results, were negative. The patient was also tested negative for HIV, cystic fibrosis and diabetes. CNPA, suspected since the second chest CT, was confirmed with the isolation of Aspergillus fumigatus in bronchoalveolar lavage cultures and on histological examination of lung biopsies. ELISA tests were positive for serum immunoglobulin (IgG) and for the specific catalase antigen of A. fumigatus. Thereafter, we retained the contribution of an allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) complicating the asthma history of this patient, colonised with Aspergillus. An antifungal treatment by voriconazole was initiated (day 7) and continued for 1 year, with a favourable outcome.

Figure 1.

(A) Initial chest CT demonstrating a complete left tension pneumothorax with an air-fluid level and a mediastinal shift, voluminous cavitations in the left lung, parenchymal infiltration in the right lung and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. (B) Chest CT 7 days after admission showing bilateral cystic bronchiectasis with mucoid impactions, multiple bilateral nodular opacities, mediastinal lymphadenopathy and persistence of voluminous cavitations in the left lung.

Outcome and follow-up

The outcome was favourable, without recurrence, with a 2-year follow-up.

Discussion

CNPA (ie, semi-invasive aspergillosis) is an indolent cavitary infectious process of the lung parenchyma secondary to local invasion by a fungus of Aspergillus sp.1 This disease is most commonly seen in patients with altered local defences from pre-existing pulmonary disease, as well as in patients with mild immunosupression.1 2 Asthma, treated with a low-dose long-term inhaled corticosteroid therapy, is a common risk factor for this clinical entity.2 3 As in our case, CNPA can also complicate an underlying ABPA, that is, the pulmonary Aspergillus overlap syndrome.3 The clinical symptoms, the history of frequent travels to Africa, and initial CT features (multifocal consolidation in multiple lobes, cavitary pulmonary nodular shadows) led to an initial diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis.4 However, clinical manifestations of CNPA, such as chronic productive cough, fever and weight loss can mimic tuberculosis.5 Moreover, the chest CT usually shows infiltrates and cavitary lesions in the upper lung lobes.5 6 Diagnostic confirmation requires histological evidence of local lung tissue invasion by Aspergillus sp. without vascular invasion, as was seen in this case. If histopathological confirmation of CNPA cannot be obtained, confirmation of the diagnosis requires the isolation of Aspergillus sp. by mycological examination of a bronchopulmonary sample.2

To the best of our knowledge there is only one case of pneumothorax secondary to semi-invasive aspergillosis published in English scientific literature.7 The occurrence of pneumothorax in our patient can be explained by a leakage of air into the pleural space from an air-filled lung cavitation, which are lesions usually encountered in CNPA.

CNPA is considered to be a formal indication for antifungal treatment.1 5 Unfortunately, there is no widely accepted standard for antifungal therapy in this disease and different treatment regimens have been suggested, such as amphotericin B and triazoles. Such drugs are usually used in patients with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.1 2 8 We chose to use voriconazole, as it appeared to be a good alternative, with an acceptable safety profile, for the treatment of CNPA in non-immunocompromised participants.2 Therapy duration should be based on clinical response, and consequently prolonged for several months if required.1 Resection of pulmonary lesions was not performed in this case because surgical treatment is not appropriate for multicavity lesions and appears to be considered only for patients who do not respond to medical therapy.1 9

In summary, this case highlights that CNPA is a diagnosis that should be considered in patients with a clinical presentation of pulmonary tuberculosis or in participants experiencing pneumothorax, especially in the context of corticosteroid treatment.

Learning points.

Chronic necrotising pulmonary aspergillosis is a rare cause of pneumothorax.

This diagnosis should be considered in patients experiencing pneumothorax with symptoms suggestive of tuberculosis and cavitary changes especially in the upper lobes.

Mild immunosuppression or inhaled corticosteroid treatment are significant contributing factors to this pathology.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors collected data, drafted the manuscript or revised it critically for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the submitted manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Saraceno JL, Phelps DT, Ferro TJ, et al. Chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis: approach to management. Chest 1997;112:541–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camuset J, Nunes H, Dombret MC, et al. Treatment of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis by voriconazole in nonimmunocompromised patients. Chest 2007;131:1435–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khousha M, Tadi R, Soubani AO. Pulmonary aspergillosis: a clinical review. Eur Respir Rev 2011;20:156–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei CJ, Tiu CM, Chen JD, et al. Computed tomography features of acute pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Emerg Med 2004;22:171–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato T, Usami I, Morita H, et al. Chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis in pneumoconiosis: clinical and radiologic findings in 10 patients. Chest 2002;121:118–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoon SH, Park CM, Goo JM, et al. Pulmonary aspergillosis in immunocompetent patients without air-meniscus sign and underlying lung disease: CT findings and histopathologic features. Acta Radiol 2011;52:756–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thurnheer R, Moll C, Rothlin M, et al. Chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis complicated by pneumothorax. Infection 2004;32:239–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trof RJ, Beishuizen A, Debets-Ossenkopp YJ, et al. Management of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in non-neutropenic critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 2007;33:1694–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denning DW. Chronic forms of pulmonary aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2001;7:25–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]