Abstract

Strict maternal transmission creates an “asymmetric sieve” favoring the spread of mutations in organelle genomes that increase female fitness, but diminish male fitness. This phenomenon, called “Mother's Curse,” can be viewed as an asymmetrical case of intralocus sexual conflict. The evolutionary logic of Mother's Curse applies to each member of the offspring microbiome, the community of maternally provisioned microbes, believed to number in the hundreds, if not thousands, of species for host vertebrates, including humans. Taken together, these observations pose a compelling evolutionary paradox: How has maternal transmission of an offspring microbiome become a near universal characteristic of the animal kingdom when the genome of each member of that community poses a potential evolutionary threat to the fitness of host males? I review features that limit or reverse Mother's Curse and contribute to resolving this paradox. I suggest that the evolution of vertical symbiont transmission requires conditions that mitigate the evolutionary threat to host males.

Maternal transmission favors the spread of mutations that favor female fitness. Tens to hundreds of microbes are transmitted maternally, posing a serious evolutionary threat to males. What limits this “Mother’s Curse?”

The genomes of mitochondria, chloroplasts, and many symbiotic microbes are transmitted maternally by host females to their offspring. Maternal transmission can be transovariole (intracellular, within the egg) or contagious, during gestation, birth, or feeding (Sonneborn 1950; Smith and Dunn 1991; Gillham 1994; O’Neill et al. 1997). Vertically transmitted (VT) symbiont lineages tend to be genetically homogeneous within hosts (Birky et al. 1983, 1989; Funk et al. 2000). Maternal uniparental transmission creates an “asymmetric sieve” wherein mutations advantageous for females, but harmful for males, can spread through a population (Cosmides and Tooby 1981; Frank and Hurst 1996; Zeh and Zeh 2005; Burt and Trivers 2006). Such mutations spread because deleterious male-specific fitness effects do not affect the response to natural selection of the maternally transmitted entities. This adaptive process favoring the transmitting sex is called Mother's Curse (MC) (Gemmell et al. 2004) and it has been referred to as an irreconcilable instance of intralocus conflict: “… exclusively maternal transmission of cytoplasmic genes (e.g., in mitochondria) can result in suboptimal mitochondrial function in males … a form of [intralocus sexual conflict] that apparently cannot be resolved, because selection on mitochondria in males cannot produce a response” (Bonduriansky and Chenoweth 2009, p. 285).

Mitochondria are ubiquitous in animals and despite the indisputable evolutionary logic of MC (Frank and Hurst 1996) there are no reported cases of sperm-killing or son-killing mitochondria (Burt and Trivers 2006). Moreover, many species of animals possess an offspring microbiome, a community of microbes transmitted uniparentally from mother to offspring at some point in development, whether prefertilization, postfertilization, or postnatal (Funkhouser and Bordenstein 2013). In some vertebrates, including humans, this community is believed to number in the hundreds of species (Funkhouser and Bordenstein 2013). Prolonged periods of maternal care, as in mammals and birds, as well as kin-structured sociality, afford many opportunities for maternal provisioning of microbes to developing offspring. The social insects, in particular, show obligate mutualisms with a microbiome that confers important nutritional benefits for its host (Baumann 2005; Engel and Moran 2013), the termites being a classic example (Ikeda-Ohtsubo and Brune 2009).

Together, the evolutionary logic of MC and the widespread existence of maternally transmitted hereditary symbioses pose a paradox for evolutionary biology. The maternally provisioned microbiome (MC) consists of tens to hundreds of genomes affording ample opportunity, along with mitochondrial and organelle genomes, for the occurrence of mutations that benefit females while harming host males. Assembling a VT community as a host nutritional or defensive adaptation requires evading MC not once, but from a continuous siege over evolutionary time. This is the Mother's Curse–microbiome (MC–MB) paradox. It conceptually affiliated with the “paradox of mutualism,” the persistence of interspecific mutualisms despite the advantages of cheating by one or the other member of the mutualism (Heath and Stinchcombe 2014). Symbiont “cheating” on only half the members of a host species, the males, might offer marginal benefits relative to wholesale cheating on both host sexes. Nevertheless, the MC–MB paradox deserves research attention.

In this review, I discuss inbreeding, kin selection, compensatory evolution, and defensive advantages against more virulent pathogens (or predators and herbivores) as means for resolving the MC–MB paradox. First, I review the simple population genetics of MC. I discuss how host inbreeding and kin selection (Unckless and Herren 2009; Wade and Brandvain 2009), alone or in concert, allow for a response to selection on male fertility and viability fitness effects of maternally transmitted genomes. As a result, inbreeding and kin selection can limit or prevent the spread of mutations in a hereditary symbiosis (Cowles 1915) that are harmful to males. I will show that, for both inbreeding and kin selection, there exist conditions that “favor the spread of maternally transmitted mutations harmful to females”; a situation that is the reverse of MC. However, many outbreeding, asocial species harbor maternally provisioned microbiomes and these solutions cannot be applied to them.

I also consider the evolution of compensatory nuclear mutations that mitigate or eliminate the harm to males of organelles or symbionts, spreading via MC dynamics. However, I find that the relative rate of compensatory evolution is only 1/4 the rate of evolution of male-harming symbionts. Thus, an evolutionary rescue of host males via compensatory host nuclear mutations requires that there be fourfold or more opportunities for compensation offered by a larger host nuclear genome. The larger the number of species in a host microbiome, the more difficult it is to entertain host nuclear compensatory mutations as a resolution of the MC–MB paradox.

Next, I consider the situation in which a deleterious, VT symbiont harms its host but prevents host infection by a more severely deleterious contagiously transmitted pathogen (Lively et al. 2005; see also Clay 1988). This is a case in which absolute harm to a host by a maternally provisioned symbiont becomes a “relative” fitness advantage. This is a scenario that may be common in hosts with speciose microbial communities, especially if each microbial species increases host resistance or outright immunity to infectious, virulent pathogens.

Finally, I discuss models of symbiont domestication and capture via the evolution of vertical transmission from an ancestral state of horizontal transmission (Drown et al. 2013). I show that the evolution of vertical transmission requires conditions that tend to restrict the capacity for male harming by symbionts. Each of these scenarios significantly expands the range of evolutionary possibilities permitted for the coevolution of host–symbiont assemblages, especially those microbial communities that are maternally, uniparentally transmitted across host generations. Unfortunately, current data do not permit discriminating among these various evolutionary responses to MC, so none can be definitively considered a resolution of the MC–MB paradox.

MC

Viability Fitness

Consider a species with alternative, maternally inherited, cytoplasmic alleles, C1 and C2, in frequencies P and Q at birth before selection in both males and females. The alleles can be haploid genes of either organelles or symbionts. Let the C1 allele have sex-specific fitness effects, s♂ and s♀, on the viability of males and females, respectively (Table 1). I assume there is no effect on fitness, positive or negative for either sex of allele C2. In males, the change from birth to adult in P is ΔP♂ = PQs♂/W♂, in which mean male fitness W♂ = 1 + s♂P. Similarly, the change in C1 allele frequency in females is ΔP♀ = PQs♀/W♀, in which W♀ = 1 + s♀P. Owing to maternal transmission, offspring receive the cytoplasmic allele of their mothers, so change in the frequency of C1 across generations is simply, ΔP♀ = PQs♀/W♀. Thus, the allele spreads as long as s♀ > 0. (Both sons and daughters receive mother’s allele, justifying the assumption of equal frequencies in both sexes at birth.) The parameter s♂ does not appear in the equation for allele frequency change, making cytoplasmic evolution blind to fitness effects on males.

Table 1.

The fundamental viability and fertility fitness models of MC

| Sire | Dam | Frequency | Sons | Daughters | Family |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Viability fitness | ||||

| C1 | C1 | P♂P♀ | 1 + s♂ | 1 + s♀ | |

| C1 | C2 | P♂Q♀ | 1 | 1 | |

| C2 | C1 | Q♂P♀ | 1 + s♂ | 1 + s♀ | |

| C2 | C2 | Q♂Q♀ | 1 | 1 | |

| Fertility fitness | |||||

| C1 | C1 | P♂P♀ | 1 | 1 | 1 + s♂ + s♀ |

| C1 | C2 | P♂Q♀ | 1 | 1 | 1 + s♂ |

| C2 | C1 | Q♂P♀ | 1 | 1 | 1 + s♀ |

| C2 | C2 | Q♂Q♀ | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Less than perfect maternal transmission or the paternal leakage of mitochondria has only a small effect on these equations. Let L be the probability that an offspring inherits the paternal mitochondria and (1 – L) be the probability that it inherits the maternal mitochondria. Then, we have P♀' = (1 + s♀)(P♀ + LX)/W♀, in which W♀ becomes (1 + P♀s♀ + LXs♀) and X is (P♂Q♀ – P♀Q♂). Here, ΔP♀ = {P♀Q♀s♀/W♀}+{LX(1 + Qs♀)/W♀}. Note that, when L = 0, we return to the equations above. The second term, added to ΔP♀ by paternal leakage, will tend to be small as long as L is small because X tends to be much less than 1. Thus, small amounts of paternal leakage do not rescue MC.

Fertility Fitness

Again, consider a species with alternative, maternally inherited, cytoplasmic alleles, C1 and C2, in frequencies P and Q in both sexes at birth. The alleles can be genes of either organelles or symbionts. Let the C1 allele have sex-specific fitness effects, s♂ and s♀, on the fertility of males and females, respectively (Table 1) and assume, again, no effect of the C2 allele. The change in C1 frequency equals ΔP = PQs♀/W, in which mean family fitness, W, equals (1 + P[s♂ + s♀]). As for the viability fitness model, the C1 allele spreads as long as s♀ > 0 and evolution is blind to this allele’s fertility effects on males. If mean fertility of the C1 × C1 family was multiplicatively determined, that is, (1 + s♂)(1 + s♀), then ΔP = PQs♀(1 + Ps♂)/W, in which W = (1 + P[s♂ + s♀] + P2s♂s♀). Although Ps♂ appears in the numerator of the ΔP expression, the term [1 + Ps♂] is always positive. Moreover, with 0 ≤ (1 + Ps♂) ≤ 1, multiplicative fertility effects impede, but do not prohibit, MC relative to the additive effects model.

For both models, MC is the case in which s♂ < 0 < s♀, wherein mutations beneficial to female fitness (0 < s♀) spread despite impairing male fitness (s♂ < 0).

MC WITH INBREEDING

Viability Fitness

For viability effects of C1 (Table 2, upper), the change in C1 allele frequency in females is ΔP♀ = PQs♀/W♀, in which W♀ = (1 + s♀P) as before. Owing to maternal transmission, offspring receive the cytoplasmic allele of their mothers, so change in the frequency of C1 across generations is also ΔP♀ = PQs♀/W♀. Thus, the allele spreads as long as s♀ > 0, and, with effects only on viability, inbreeding has no effect at all on the rate of spread of C1. Neither f nor s♂ appears in the equation for allele frequency change, making cytoplasmic evolution blind to viability fitness effects on males and inbreeding.

Table 2.

Inbreeding and the viability and fertility fitness models of MC

| Sire | Dam | Frequency | Sons | Daughters | Family |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Viability fitness | ||||

| C1 | C1 | P♂P♀ + Q♂P♀f | 1 + s♂ | 1 + s♀ | |

| C1 | C2 | P♂Q♀(1 – f) | 1 | 1 | |

| C2 | C1 | Q♂P♀(1 – f) | 1 + s♂ | 1 + s♀ | |

| C2 | C2 | Q♂Q♀ + P♂Q♀f | 1 | 1 | |

| Fertility fitness | |||||

| C1 | C1 | P♂P♀ + Q♂P♀f | 1 | 1 | 1 + s♂ + s♀ |

| C1 | C2 | P♂Q♀(1 – f) | 1 | 1 | 1 + s♂ |

| C2 | C1 | Q♂P♀(1 – f) | 1 | 1 | 1 + s♀ |

| C2 | C2 | Q♂Q♀ + P♂Q♀f | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Fertility Fitness

For this case (Table 2, lower), we find the change in C1 frequency to be ΔP♀ = PQ(s♀ + fs♂)/W♀, in which W♀ = 1 + (s♀ + s♂)P. Whenever there is inbreeding (f > 0), the effect of the C1 allele on sons’ fertility “differentially” affects the fertility of their C1 sisters. (Note that, when there is no inbreeding [f = 0], I recover the earlier equation.) Change in C1 frequency will be positive as long as the quantity (s♀ + fs♂) is positive. Earlier, Wade and Brandvain (2009) remarked on the relationship between this condition and Hamilton’s rule (Hamilton 1967) when the effects on female fertility are positive, but those on males are negative. Recall that, MC is the case in which s♂ < 0 < s♀. For gene frequency change to be positive in this case, the fitness benefit of C1 to a female, s♀, must exceed the product of the relatedness to her mate, f, times the fitness cost of C1 to her mate, s♂. Thus, inbreeding sets limits on MC. There are clear parallels between the restrictions on cytoplasmic male effects of MC with inbreeding and Hamilton’s (1967) discovery that inbreeding limits X-linked or Y-linked selfish, sex ratio distorters.

In fact, there are conditions in which inbreeding favors maternally inherited cytoplasmic alleles with “deleterious” effects on females, but positive effects on males. Change in C1 frequency is positive when s♀ < 0 < s♂, as long as fs♂ exceeds s♀, which is the reverse of MC.

NUCLEAR COMPENSATORY MUTATIONS

Consider alternative host nuclear alleles, A1 and A2, such that the A1 allele acts additively to restore the fitness of C1 males from (1 + s♂) to 1, in which s♂ < 0. More specifically, the A1A1C1 homozygotes have fitness equal to 1, A1A2C1 heterozygotes have fitness of (1 + [s♂/2]), and A2A2C1 homozygotes have fitness equal to (1 + s♂). The rate of evolution of the compensatory A1 allele is ΔPA1 = PC1PA1 PA2 s♂/4W♂, in which W♂ = (1 + PA1s♂). The rate of compensatory evolution relative to the evolution of male-harming organelles or symbionts depends on the relative values of s♀ and s♂. If the benefit to females from C1 equaled the harm to males, then the rate of compensatory evolution is only (¼PC1) that of the organelle or symbiont. The rate of evolution of the A1 allele is diminished for three reasons. First, because its fitness advantage is only in the male sex, copies of A1 in females are not screened by natural selection. All else being equal, this reduces the rate of evolution by a factor of ½ (Wade 1998; Demuth and Wade 2005; van Demuth and Wade 2007; Cruickshank and Wade 2008). Second, only those copies of the A1 allele in males that occur on the C1 background enjoy a fitness benefit. This reduces the rate of evolution by a factor of PC1. And, third, the fitness difference between A1A1C1 and A2A2C1 homozygotes is s♂, a scale set by the haploid-harming organelle or symbiont. Although the scale of the fitness difference between nuclear homozygotes can be either s or 2s without affecting ΔP, the scale is fixed by fitness effects caused by the other genome. This reduces the rate of evolution by another factor of 1/2.

Although nothing is known about the rate of mutation of organelles and symbionts to male-harming, female-beneficial states, it is unlikely that differential mutation rates, in which µnuclear > µsymbiont, can offset the large reduction in rate (¼PC1) of host nuclear compensatory evolution. In most animals, the mutation-rate differential runs in the opposite direction (i.e., µmitochondria > µnuclear), and it is likely that the same is true for most symbionts. Moreover, if initially µnuclear = K(µsymbiont), in which K is the number of symbionts in the microbiome, once the maternally provisioned microbiome reached (K/4)-species, the initial advantage of nuclear compensatory evolution over male-harming organelle and symbiont evolution would be eroded.

MC AND KIN SELECTION

Consider a species living in matrilineal family groups in which sons make essential contributions to the viability of their female relatives. Let C1 and C2 be alternative, maternally inherited, cytoplasmic alleles, in frequencies P and Q, and let f be the inbreeding parameter. The C1 allele has two viability fitness effects, s♂ and s♀, one on the viability of C1 males and the other on that of C1 females, respectively. Additionally, let sF♂ be the effect of viable C1 males on the fitness of their sisters; thus, sF♂ is a kin selection or family effect. We assume that only surviving males influence the fitness of their sisters, so that the effect on family fitness is modulated by the survival of C1 males and becomes {1 + sF♂(1 + s♂)} (see Table 3). We further assume that family and individual female viability fitnesses are multiplicative.

Table 3.

Model I: Kin selection in which sons assist sisters

| Sire | Dam | Frequency | Family fitness | Sons | Daughters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | |||||

| C1 | C1 | P♂P♀ +Q♂P♀ f | 1 + sF♂(1 + s♂) | 1 + s♂ | 1 + s♀ |

| C1 | C2 | P♂Q♀(1 – f) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| C2 | C1 | Q♂P♀(1 – f) | 1 + sF♂(1 + s♂) | 1 + s♂ | 1 + s♀ |

| C2 | C2 | Q♂Q♀ + P♂Q♀f | 1 | 1 | 1 |

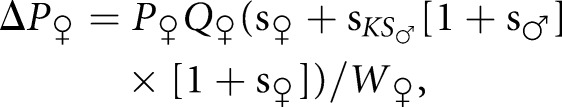

With these assumptions, the general equation describing the one-generation change in allele frequency caused by selection is

|

(1) |

in which mean female fitness W♀ = 1 + P♀[s♀ + sKS♂{1 + s♂}{1 + s♀}]. This is also the change in frequency of C1 between generations because the frequency of the C1 allele in daughters of the next generation equals the frequency in the surviving females.

Here, inbreeding has no effect on the rate of evolution because the frequency of helpful sons born to C1 mothers is not affected by the mating system. When sKS♂ is 0, ΔP♀ reduces to the classic formula P♀Q♀s♀/W♀ (Wright 1969, p. 163, Equation [6.1]; or Hedrick 2000, p. 105). The direct effects of C1 on male viability, s♂, have no effect on the evolution of C1 unless males are helping (sKS♂ > 0) or harming (sKS♂ < 0) their sisters. In the absence of the indirect effect on sisters (sKS♂ = 0), maternal transmission precludes an evolutionary response to male-specific viability selection (Frank and Hurst 1996; Burt and Trivers 2006).

Some taxa with mutualistic microbiomes have both inbreeding and male-helping behavior, for example, termites (Reilly 1987), but there are also taxa with microbiomes that are neither social nor inbreeding (Funkhouser and Bordenstein 2013). Resolving the MC–MB paradox in these taxa may be more difficult. I discuss two additional possibilities in the next two sections.

COMPETITIVE COEXISTENCE OF SYMBIONTS AND PATHOGENS

Members of the maternally provisioned microbiome are believed to be derived from free-living forms by a process sometimes referred to as “symbiont capture” or “symbiont domestication” (Maynard Smith and Szathmáry 1998). Importantly, vertical transmission favors decreased symbiont virulence because it aligns the evolutionary interests of host and symbiont (Smith 2007). For this reason, VT symbionts must enhance host fitness or they will be lost from the host population in the same manner as a deleterious mitochondrial gene (Fine 1975; Ewald 1987; Lipsitch et al. 1995, 1996). The nutritional benefits of the maternally provisioned microbiome have long been considered (reviewed in Funkhouser and Bordenstein 2013). Defensive benefits to the offspring provided by maternal symbiont transmission are also well known (Clay 1988; Clay and Schardl 2002). There is one such defensive benefit that increases host relative fitness that may be quite general, namely, a host fitness benefit that derives from possessing a VT symbiont, which prevents host infection by another free-living and more virulent member of the same or a similar taxon (Lively et al. 2005).

Free-living, virulent parasites often adapt to the most frequently encountered host genotypes, and they are believed to be one of the evolutionary forces driving the maintenance of sexual reproduction (Lively 2010). Although some such parasites encounter one host sex more than the other and, subsequently, specialize on that host sex (Duneau et al. 2010), many free-living, virulent parasites are host generalists and not host sex-specific in their incidence or fitness effects. The presence of infectious free-living virulent parasites can allow a VT symbiont, which prevents host infection by the free-living virulent form, to increase in frequency. Moreover, the rate of its spread increases as the fidelity of maternal transmission increases (Lively 2010). Importantly, in the models explored by Lively (2010), not only does the virulent form persist in the host population (albeit at very low frequency), but its virulence is also increased.

Once a symbiont species becomes a member of the maternally provisioned microbiome, the origin in its genome of male-specific harmful mutations benefiting host females becomes a possibility. However, the spread of such a male-harming mutation allows the coexisting, virulent species to specialize on host females (Duneau et al. 2010), which become the more abundant host sex as the male-harming mutation spreads. This results in a diminishing fitness advantage to host females of the male-harming symbiont. Once the fitness benefit to host females is lost, the male-harming mutation stops spreading. The enhanced virulence of the free-living pathogen (Lively 2010) may accelerate this process.

Overall, the harmful effects of the endosymbiont on host males are counterbalanced by the harmful effects of the free-living pathogen on host females. Thus, restriction of male-harming mutations, originating in the genomes of members of the maternally provisioned microbiome, may depend on the female-biased, sex-specific counteradaptations of the free-living virulent species, excluded from the host by its prior occupancy by the VT defensive symbiont.

This scenario accounts for both the high species diversity of the maternally provisioned microbiome and the restriction of the male-harming mutations arising from it. Like models for the evolution of sex, however, it depends on the virulence of a free-living pathogen relative to that of the VT symbiont. It requires a careful balance of sex-specific, deleterious effects on host fitness. The plausibility of establishing such an evolutionary balance for each member of the maternally provisioned microbiome remains to be explored in both theory and experiment.

EVOLUTION OF TRANSMISSION MODE IN OBLIGATE SYMBIONTS

Special conditions appear to be necessary to evolve from an ancestral state of horizontal transmission to a derived state of vertical transmission (Drown et al. 2013). These conditions are relevant to understanding the evolutionary origins of the maternally transmitted microbiome, and they may contribute to resolving the MC–MB paradox by reducing the capacity of a VT symbiont to generate male-harming, but female-beneficial mutations.

One necessary condition is transgenomic epistasis for fitness between host and symbiont genes, like that characteristic of matching allele models in host-pathogen models (Agrawal and Lively 2002) and additive-by-additive classical epistasis for fitness in population genetic models (Drown et al. 2013). Unless there are gene combinations that enhance the fitness of both host and symbiont, vertical transmission does not evolve from an ancestral state of horizontal transmission. It is selection favoring the mutually advantageous combinations that generates the indirect selection on mode of transmission.

A second necessary condition is repeated mutation in the genomes of both host and symbiont. Without repeated mutation, advantageous transgenomic combinations are quickly fixed and indirect selection favoring vertical transmission ceases. Repeated mutation is necessary for maintaining an influx of advantageous, transgenomic gene combinations in much the same way that rapid adaptation of virulent parasite genotypes to common host genotypes is required for the maintenance of sex. With a continuous influx of such mutations, vertical transmission is a stable evolutionary endpoint for a matching alleles model (Drown et al. 2013).

With regard to host-harming mutations, this mutational phase acts as an evolutionary sieve, removing deleterious transgenomic combinations and preserving favorable ones. Vertical transmission evolves only to the extent that mutational combinations arise and successfully pass through this sieve. This period in the evolution of maternally transmitted symbiont communities can be fairly long, so that many mutational combinations, in both host and symbiont, are screened. This sieve may represent such a significant barrier to admission of a species to the VT symbiont community of its host that very few species with a capacity for host male-harming mutations are admitted. Conversely, many species with a capacity for host-harming mutations are excluded.

This theory proposes a mutational sieve that occurs earlier in the process of the evolution of vertical transmission that leaves little, if any, genetic material for the “asymmetric sieve” of MC. The study of symbionts with both modes of transmission (Lipsitch et al. 1996) will be necessary to determine whether or not membership in the maternally provisioned biome is exclusive to only a few symbiont species. It will also help determine whether or not the reduction in genome size, often observed in such symbionts (Sloan and Moran 2012), restricts their capacity for generating host male-harming mutations.

CONCLUSIONS

The evolutionary logic of MC and the widespread existence of maternally provisioned symbioses pose a paradox for evolutionary biology. The high species diversity of the microbiome affords ample opportunity for the occurrence of mutations that benefit host females while harming host males. Host nuclear compensatory mutations that mitigate the male-specific fitness effects of VT symbionts may exist and spread, but their rate of evolution is less than 1/4 that of the male-harming symbiont mutations they are meant to counter.

Recent theory (Unckless and Herren 2009; Wade and Brandvain 2009) has shown that, whenever host males affect the fitness of female relatives or whenever there is inbreeding, there are evolutionary restrictions placed on MC. However, the existence of these effects alone cannot resolve the MC–MB paradox because many host species with a maternally provisioned microbiome are neither social nor inbreeding.

In this review, I have proposed two possible evolutionary scenarios that may contribute to the resolution of the MC–MB paradox: (1) the competitive coexistence of symbionts and pathogens, and (2) the mutational exclusivity of membership in the maternally provisioned microbiome. Although each is plausible, both proposals are speculative and require additional theoretical and empirical investigation. Each makes different empirical predictions. For example, the competitive coexistence hypothesis predicts that some members of the maternally provisioned community exclude infection by more virulent free-living pathogens. This could be tested by comparing the susceptibility of hosts with and without a specific VT symbiont. This is not sufficient, however, to establish the competitive coexistence hypothesis as true. A VT symbiont and one or more free-living pathogens must show sexually antagonistic effects on their host, with the VT symbiont differentially harming host males and the free-living pathogens differentially harming host females. The eradication of a free-living pathogen may result in the loss of a less virulent symbiont and, at least in some instances, should result in the spread of male-harming mutations caused by its VT counterpart.

Experimentally establishing the mutational exclusivity of membership in the microbiome may well be more difficult. But, the study of symbionts with both modes of transmission (Lipsitch et al. 1996) may offer the best opportunity. Those with higher levels of vertical transmission should be farther along in the evolutionary process than those with lower levels. The former should be capable of fewer host-harming mutations than the latter and such a difference might be revealed with replicated, mutation-accumulation experiments. On the other hand, if membership in the maternally provisioned biome is not exclusive, many member species will be of recent origin. Comparison of the communities of taxonomically related hosts may be useful in addressing this possibility.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank the members of the Wade laboratory, Devin Drown, Amy Dapper, Doug Drury, and Jeff Adrion, and my colleagues Yaniv Brandvain, Curt Lively, and David E. McCauley for their thoughtful feedback on these ideas. I gratefully acknowledge the support of National Institutes of Health grant R01GM084238.

Footnotes

Editors: William R. Rice and Sergey Gavrilets

Additional Perspectives on The Genetics and Biology of Sexual Conflict available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Agrawal A, Lively CM 2002. Infection genetics: Gene-for-gene versus matching-alleles models and all points in between. Ecol Evol Res 4: 79–90 [Google Scholar]

- Baumann P 2005. Biology bacteriocyte-associated endosymbionts of plant sap-sucking insects. Annu Rev Microbiol 59: 155–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birky CW, Maruyama T, Fuerst 1983. An approach to population and evolutionary genetic theory for genes in mitochondria and chloroplasts, and some results. Genetics 103: 513–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birky CW, Fuerst P, Maruyama T 1989. Organelle diversity under migration, mutation, and drift: Equilibrium expectations, approach to equilibrium, effects of heteroplasmic cells, and comparison to nuclear genes. Genetics 121: 613–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonduriansky R, Chenweth SF 2009. Intralocus sexual conflict. Trends Ecol Evol 24: 280–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt A, Trivers R 2006. Genes in conflict. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA [Google Scholar]

- Clay K 1988. Fungal endophytes of grasses: A defensive mutualism between plants and fungi. Ecology 69: 10–16 [Google Scholar]

- Clay K, Schardl CL 2002. Evolutionary origins and ecological consequences of endophyte symbiosis with grasses. Am Nat 160: S99–S127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmides LM, Tooby J 1981. Cytoplasmic inheritance and intragenomic conflict. J Theor Biol 89: 83–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles HC 1915. Hereditary symbiosis. Bot Gaz 59: 61–63 [Google Scholar]

- Cruickshank T, Wade MJ 2008. Microevolutionary support for a developmental hourglass: Gene expression patterns shape sequence variation and divergence in Drosophila. Evol Dev 10: 583–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuth J, Wade MJ 2007. Maternal expression increases the rate of bicoid evolution by relaxing selective constraint. Genetica 129: 37–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieter D 2013. The epidemiology and evolution of symbionts with mixed-mode transmission. Annu Rev Ecol Evol System 44: 623–643 [Google Scholar]

- Drown DM, Zee PC, Brandvain Y, Wade MJ 2013. Evolution of transmission mode in obligate symbionts. Ecol Evol Res 15: 43–59 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duneau D, Luijckx P, Ruder LF, Ebert D 2010. Sex-specific effects of a parasite evolving in a female-biased host population. BMC Biol 10: 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel P, Moran NA 2013. The gut microbiota of insects—Diversity in structure and function. Microbiol Rev 37: 699–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald PW 1987. Transmission modes and the evolution of the parasitism–mutualism continuum. Ann NY Acad Sci 503: 295–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine PEM 1975. Vectors and vertical transmission: An epidemiological perspective. Ann NY Acad Sci 266: 173–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank SA, Hurst LD 1996. Mitochondria and male disease. Nature 383: 224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk DJ, Helbling L, Wernegreen JJ, Moran NA 2000. Intraspecific phylogenetic congruence among multiple symbiont genomes. Proc R Soc Lond B 267: 2517–2521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funkhouser LJ, Bordenstein SR 2013. Mom knows best: The universality of maternal microbiome transmission. PLoS Biol 11: e1001631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemmell NJ, Metcalf VJ, Allendorf FW 2004. Mother’s curse: The effect of mtDNA on individual fitness and population viability. Trends Ecol Evol 19: 238–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillham MW 1994. Organelle genes and genomes. Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton WD 1967. Extraordinary sex ratios. A sex-ratio theory for sex linkage and inbreeding has new implications in cytogenetics and entomology. Science 156: 477–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath KD, Stinchcombe JR 2014. Explaining mutualism variation: A new evolutionary paradox? Evolution 68: 309–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick PW 2000. Genetics of populations. Jones and Bartlett, Sudbury, MA [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda-Ohtsubo W, Brune A 2009. Cospeciation of termite gut flagellates and their bacterial endosymbionts: Trichonympha species and “Candidatus Endomicrobium trichonymphae.” Mol Ecol 18: 332–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitch M, Nowak MA, Ebert D, May R 1995. The population dynamics of vertically and horizontal transmitted parasites. Proc R Soc Lond B 260: 321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitch M, Siller S, Nowak MA 1996. The evolution of virulence in pathogens with vertical and horizontal transmission. Evolution 50: 1729–1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lively CM 2010. A review of Red Queen models for the persistence of obligate sexual reproduction. Heredity 101: S13–S20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lively CM, Clay K, Wade MJ, Fuqua C 2005. Competitive coexistence of vertically and horizontally transmitted parasites. Ecol Evol Res 8: 1183–1190 [Google Scholar]

- Maynard Smith J, Szathmáry E 1998. The major transitions in evolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill SL, Hoffmann AA, Werren JH 1997. Influential passengers: Inherited microorganisms and arthropod reproduction. Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly LM 1987. Measurements of inbreeding and average relatedness in a termite population. Am Nat 130: 339–349 [Google Scholar]

- Sloan JE, Moran NA 2012. Genome reduction and co-evolution between the primary and secondary bacterial symbionts of psyllids. Mol Biol Evol 29: 3781–3792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J 2007. A gene’s-eye view of symbiont transmission. Am Nat 170: 542–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JE, Dunn AM 1991. Transovariol transmission. Parasitol Today 7: 146–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonneborn TM 1950. Partner of the genes. Sci Am 183: 30–39 [Google Scholar]

- Unckless RL, Herren JK 2009. Population genetics of sexually antagonistic mitochondrial mutants under inbreeding. J Theor Biol 260: 132–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dyken JP, Wade MJ 2010. Quantifying the evolutionary consequences of conditional gene expression in time and space. Genetics 184: 557–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade MJ 1998. The evolutionary genetics of maternal effects. In Maternal effects (Mousseau J, Fox C, eds.), pp 5–21 Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Wade MJ, Brandvain Y 2009. Reversing mother’s curse: Selection on male mitochondrial fitness effects. Evolution 63: 1084–1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S 1969. Evolution and genetics of populations. Vol. II. University of Chicago Press, Chicago [Google Scholar]

- Zeh JA, Zeh DW 2005. Maternal inheritance, sexual conflict and the maladapted male. Trends Genet 21: 281–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]