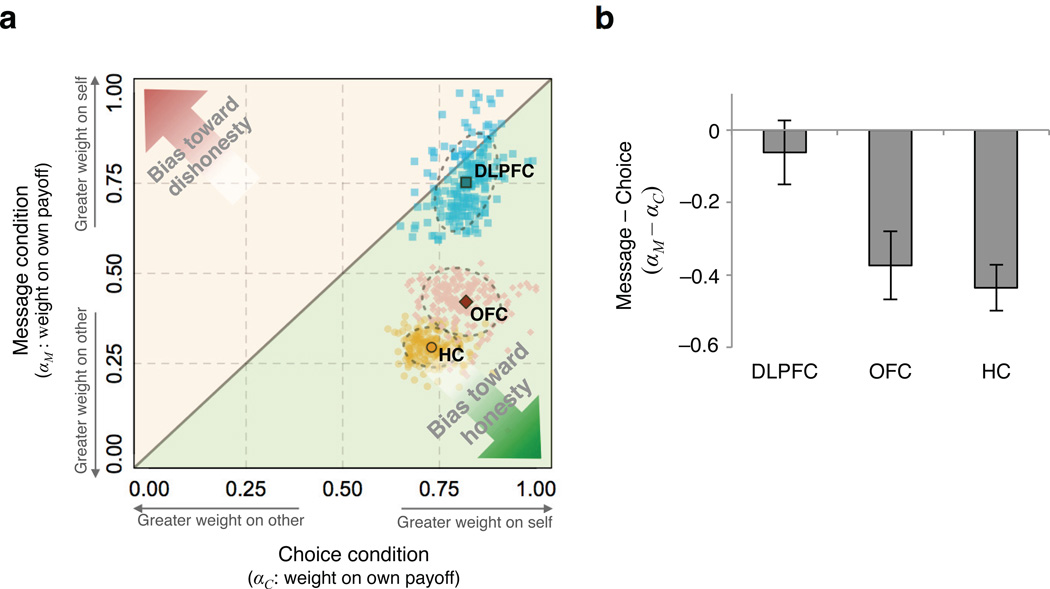

Figure 3.

Computational modeling. (a) Green shaded region captures willingness to sacrifice own payoffs to send the true message, i.e., bias toward honesty, where weight on self-interest in the Message condition (αM) is reduced relative to the Choice condition (αC). Conversely, red shaded region captures willingness to sacrifice own payoffs to send the false message, i.e., bias toward dishonesty, where αM is greater than αC. All cohorts placed similar weights on one’s own payoff in the Choice condition (DLPFC: . 82 ± .05, OFC: . 79 ± .07 and healthy comparison: . 73 ± .05). In the Message condition, OFC and healthy participants showed a significant reduction in weight on own payoff, whereas DLPFC participants did not differ significantly between the two conditions (DLPFC: . 75 ± .09; OFC: .43 ± .06; and healthy comparison:. 29 ± .04). Solid points represent parameter estimates and smaller points represent bootstrap pseudo-sample estimates. Dashed ellipses correspond to bootstrapped standard errors. (b) Taking paired-wise differences in pseudo-sample estimates of αM and αC, OFC and healthy participants showed significantly lower weight on own payoff in the Message condition as compared to the Choice condition (p < .01, two-tailed), whereas the DLPFC cohort did not exhibit a significant difference (p > .05, two-tailed; all error bars indicate bootstrap standard errors).