Abstract

Treatment of left ventricle wall rupture is very challenging, ruptured myocardial tissue is usually of poor quality and has a high risk of total rupture when being sutured. Furthermore, rapid decision-making is needed under stressful conditions. We present a series of three cases demonstrating the feasibility of using only hemostatic collagen sponges for the management of left ventricle wall rupture. All patients we Caucasian males, two patients were 65 years and one patient was 67 years old at the time of surgery. This report contains the first video images of solely use of hemostatic collagen sponges to seal a left ventricle wall rupture. Implication of our case series could be that the indication to use hemostatic collagen sponges, could be broadened towards other surgical specialties where suturing ruptured tissue can be difficult.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13019-014-0136-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Left ventricle wall rupture, Sutureless, Collagen sponges

Background

Left ventricular free wall rupture (FWR) can be found in 26 percent of the cases in which patients die of acute myocardial infarction [1]. Overall incidence of FWR ranges from 4-6% [2]. Clinical course of FWR is highly variable but in most circumstances, it is a medical emergency mandating immediate treatment. Majority of patients surviving FWR had a contained ventricular wall rupture. Tissue surrounding the injury site is usually in poor condition and vulnerable to manipulation. Surgical techniques, such as suture or ligature can be sometimes ineffective in cases of poor tissue quality, increasing the risk of enlargement of the rupture. Short-term survival secondary to surgery can be as high as 76%, in patients with sub-acute FWR, long-term survival, however, is still poor in the end only 48.5% survive hospital stay [3].

Case presentation

We present three patients who presented for emergency surgery for pericardial tamponade due to FWR. In two cases, FWR occurred secondary to a myocardial infarction. In both cases, diagnosis was confirmed by both trans-thoracic echocardiography (TTE) and pericardiocentesis. Our third case had an FWR as a complication during minimally invasive surgery, which was converted to a median sternotomy.

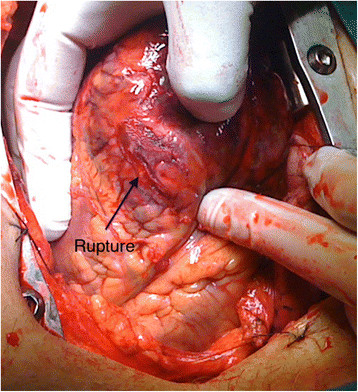

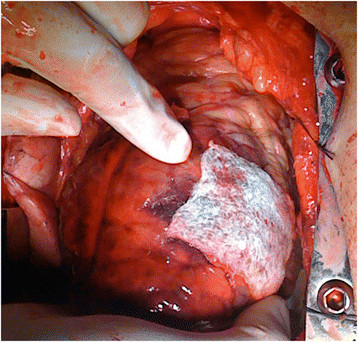

Patient 1, a 67-year-old Caucasian male was operated under clinical conditions of a tamponade. He was referred for surgery after dissection of his left anterior descending (LAD) artery during a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Indication for PCI was acute anterior wall infarction. Tissue quality in the injured area was deemed inadequate for suturing (Figure 1). Decision was made to use a collagen sponge (Tachosil®) to adhere the ruptured tissue and achieve hemostasis (Figure 2, Additional file 1).

Figure 1.

A left ventricle wall rupture (arrow) can be seen, injury site is surrounded by bruised tissue.

Figure 2.

Hemostasis in the injured area is achieved after application of the collagen sponge.

Patient 2, a 65-year-old Caucasian male presented one week after a large anterior myocardial infarction with clinical signs of a cardiac tamponade. There was extensive infarcted tissue seen in the mid-range area of the LAD. A hemostatic collagen sponge (Tachosil®) was applied on the damaged tissue to stop bleeding. Subsequently, a fibrin sealant (Tissucol®) was used to adhere the injured area to the pericardium.

Patient 3, a 65-year-old Caucasian male underwent minimally invasive surgery for mitral valve repair. At the end of surgery after weaning off bypass severe bleeding from the pericardial region was noticed. The area of bleeding could not be clearly localized, a sternotomy was deemed necessary. Cardiac inspection revealed a rupture in the inferolateral wall. We used a hemostatic matrix sealant (Floseal®) to effectively stop bleeding and a collagen sponge (Tachosil®) to adhere the epicardium onto the injured area.

All patients survived treatment and in hospital stay, no reoperation was needed for bleeding. Routine transthoracic echocardiography months after surgery did not reveal any ventricle aneurysm formation.

Conclusions

Our cases demonstrated the feasibility of using collagen sponges and hemostatic matrix sealant, for effective hemostatic sealing of ventricular free wall ruptures, even if tissue quality is poor.

Collagen sponges have been used in different surgical specialties ranging from urology, gynecology and liver surgery [4]-[6]. The use of collagen sponges in cardiac surgery is not new, its safety has been assessed in different cardiothoracic procedures [7]-[9]. However, the indication for using collagen sponges in ventricle wall rupture is becoming more common now, with similar good results using Tachosil®, for FWR [10]-[12]. The novelty in our case series was that one of our patients has an acute left ventricle wall rupture during a minimal invasive procedure not related to myocardial infarction. In this case time was of essence and the patch could be placed very rapidly with good results. Unlike other reports we did not encounter any complications within the first few months of follow-up [13],[14]. There are several issues associated with patients presenting with ventricular free wall rupture. First, these patients are usually presented as cardiac emergencies requiring immediate treatment. Second, the underlying culprit is most likely myocardial infarction implying poor ventricle function and third, emergency anticoagulation therapy is normally commenced on the base of an infarction before these patients arrive at a hospital, which further complicates intra-operative hemostasis. Free wall ruptures, especially in the occurrence of myocardial infarction, implies poor tissue quality, suturing infarction tissue makes it prone for further rupture.

The American Food and Drug Administration approved collagen sponges for use as an adjunct to hemostasis in cardiovascular surgery when control of bleeding by standard surgical techniques, such as suture, ligature or cautery, is ineffective or impractical. However, the sole use of collagen sponges and other hemostatic compounds for ventricular wall repair is an off-label use. Although other options exist to treat ventricle wall rupture, such as bioglue® or bovine pericardial patch, collagen sponges may be alternative in those centers where it is available.

Care should be taken to understand the caveats associated with the surgical approach emergency cases. When using bioglue® or bovine patches the patient should be on cardiopulmonary bypass with total decompression of the heart. The patch is then applied to a bloodless, motionless operative site and a “time to set” is needed before the heart is filled and ventricular contraction resumed. These extra minutes will ensure that the patch is firmly attached to the myocardial surface. In our cases the Tachosil® patch was applied directly on a beating heart, while two of the patients were not even on by-pass. The collagen sponge coated surface ensured direct attachment to the ventricle wall. Application of local pressure was of short duration, with good outcome results. Post-operative echocardiography demonstrated wall motion abnormality around the area of the rupture; however it did not demonstrate myocardial constriction related to the patch.

In case of ventricular free wall rupture, it is up to the surgeon to judge if repair can be undertaken using more conservative methods. However, if tissue quality makes a repair seem unlikely this new treatment method introduces a new option in operative management. Our cases have demonstrated that collagen sponges together with other hemostatic adjuncts can be a viable option as sole treatment for left ventricular bleeding, in patients with poor tissue quality, especially when there is limited time.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of the journal of cardiothoracic surgery.

No Ethical approval was required, we used collagen patches in an emergency setting. The decision to use the patch was made on the spot.

Our patients were not part of any clinical trial, hence no ethical committee approval was required. The patches we used have CE markings and are approved for medical/surgical use in Europe and USA.

Additional file

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: The video shows application of wound inspection of a LV rupture (patient 1) after application of a Tachosil® hemostatic sponge on a beating heart. The sponge is firmly adhered to the LV wall and no bleeding is seen. (mp4 358 KB)

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Abbreviations

- FWR

Left ventricular free wall rupture

- TTE

Trans-thoracic Echocardiography

- PCI

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- LAD

Left anterior descending coronary artery

Footnotes

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors have substantially contributed to the design of the paper, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting and critical revision. Every author gave his or her final approval for submission of this manuscript. RB and JJ prepared the manuscript, performed literature search and provided the basis of the article, BD and IH have been involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, EH and IH performed the surgeries, provided intellectual input and gave final approval for publication of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Remco Bergman, Email: r.bergman@umcg.nl.

Jayant S Jainandunsing, Email: j.s.jainandunsing@umcg.nl.

Bozena D Woltersom, Email: b.d.woltersom@umcg.nl.

Inez J den Hamer, Email: i.j.den.hamer@umcg.nl.

Ehsan Natour, Email: e.natour@umcg.nl.

References

- 1.Stevenson WG, Linssen GC, Havenith MG, Brugada P, Wellens HJ. The spectrum of death after myocardial infarction: a necropsy study. Am Heart J. 1989;118:1182–1188. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(89)90007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Figueras J, Alcalde O, Barrabes JA, Serra V, Alguersuari J, Cortadellas J, Lidon RM. Changes in hospital mortality rates in 425 patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction and cardiac rupture over a 30-year period. Circulation. 2008;118:2783–2789. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.776690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez-Sendon J, Gonzalez A, Lopez de Sa E, Coma-Canella I, Roldan I, Dominguez F, Maqueda I, Martin Jadraque L. Diagnosis of subacute ventricular wall rupture after acute myocardial infarction: sensitivity and specificity of clinical, hemodynamic and echocardiographic criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:1145–1153. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90315-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simo KA, Hanna EM, Imagawa DK, Iannitti DA. Hemostatic agents in hepatobiliary and pancreas surgery: a review of the literature and critical evaluation of a novel carrier-bound fibrin sealant (TachoSil) ISRN Surg. 2012;2012:729086. doi: 10.5402/2012/729086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mele E, Ceccanti S, Schiavetti A, Bosco S, Masselli G, Cozzi DA. The use of Tachosil as hemostatic sealant in nephron sparing surgery for Wilms tumor: preliminary observations. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:689–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuglsang K, Dueholm M, Staehr-Hansen E, Petersen LK. Uterine healing after therapeutic intrauterine administration of TachoSil (hemostatic fleece) in cesarean section with postpartum hemorrhage caused by placenta previa. J Pregnancy. 2012;2012:635683. doi: 10.1155/2012/635683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rousou JA. Use of fibrin sealants in cardiovascular surgery: a systematic review. J Card Surg. 2013;28:238–247. doi: 10.1111/jocs.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maisano F, Kjaergard HK, Bauernschmitt R, Pavie A, Rabago G, Laskar M, Marstein JP, Falk V. TachoSil surgical patch versus conventional haemostatic fleece material for control of bleeding in cardiovascular surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;36:708–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuschel TJ, Gruszka A, Hermanns-Sachweh B, Elyakoubi J, Sachweh JS, Vazquez-Jimenez JF, Schnoering H. Prevention of postoperative pericardial adhesions with TachoSil. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pocar M, Passolunghi D, Bregasi A, Donatelli F. TachoSil for postinfarction ventricular free wall rupture. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;14(6):866–867. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivs085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raffa GM, Tarelli G, Patrini D, Settepani F. Sutureless repair for postinfarction cardiac rupture: a simple approach with a tissue-adhering patch. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145(2):598–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishizaki K, Seki T, Fujii A, Nishida Y, Funabiki M, Morikawa Y. Sutureless patch repair for small blowout rupture of the left ventricle after myocardial infarction. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;52(5):268–271. doi: 10.1007/s11748-004-0123-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aoyagi S, Tayama K, Otsuka H, Okazaki T, Shintani Y, Wada K, Kosuga K. Sutureless repair for left ventricular free wall rupture after acute myocardial infarction. J Card Surg. 2014;29(2):178–180. doi: 10.1111/jocs.12286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakaguchi G, Komiya T, Tamura N, Kobayashi T. Surgical treatment for postinfarction left ventricular free wall rupture. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85(4):1344–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: The video shows application of wound inspection of a LV rupture (patient 1) after application of a Tachosil® hemostatic sponge on a beating heart. The sponge is firmly adhered to the LV wall and no bleeding is seen. (mp4 358 KB)