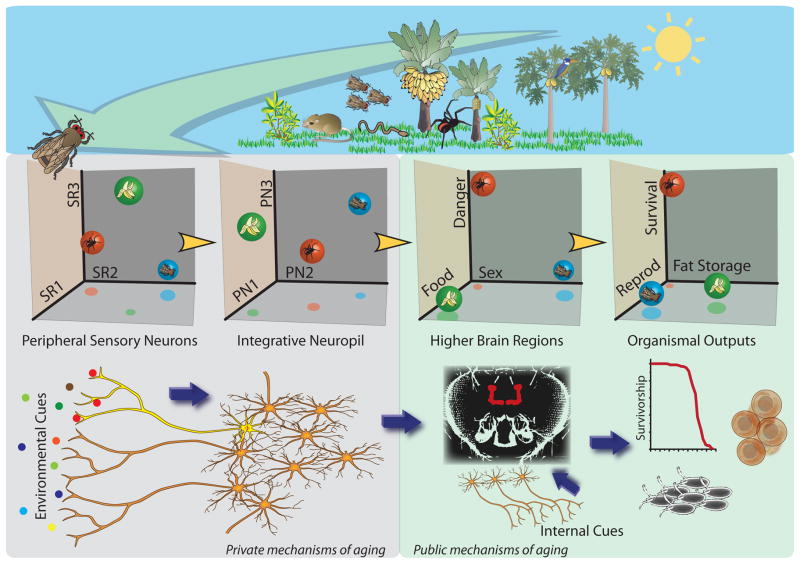

Figure 2. Detecting, decoding and interpreting sensory input to modulate aging and physiology.

Organisms are exposed to a wide-range of sensory stimuli from the environment. These inputs are detected by one or more peripheral sensory receptors that are tuned to specific ligands and that generate a characteristic set of neural responses in peripheral sensory neurons. Here, using the fly to illustrate phenomena that we believe are more general, we depict the processing of three hypothetical odorants (spider, fly, and banana) following their activation of three arbitrary sensory receptors (SR1, SR2, and SR3) to different degrees. The actual dimension of these spaces is much larger; flies, for example, express over sixty odorant receptors, while mice express over one-thousand. Neural signals from peripheral sensory neurons are processed in various types of integrative neuropil (e.g., the antennal lobe in flies, ring gland in worms, and olfactory bulb in mammals) to improve signal to noise ratio, maximize sensitivity, and enhance signal discrimination. Second-order neurons then pass the refined signals to higher regions of the brain (e.g., the mushroom bodies in flies and hypothalamus in mammals) where they are interpreted and perceived as ecologically relevant cues. From here, the cues may be integrated further with previous experience or with information about the nutritional and metabolic status of the organism, perhaps through internal sensory receptors. Very similar to behavior, the result may be to generate rapid and long-lasting effects on various aspects of organism physiology, including those that promote survival, reproductive output, and/or fat storage. We postulate that the mechanisms that are recruited to respond to perceived cues are evolutionary conserved “public” mechanisms, while those that are highly tuned to process specific signals are “private” and unique to each organism. Three-dimensional odor space diagrams are based on and expanded from ideas presented in Masse, Turner, and Jefferis (Masse et al 2009).