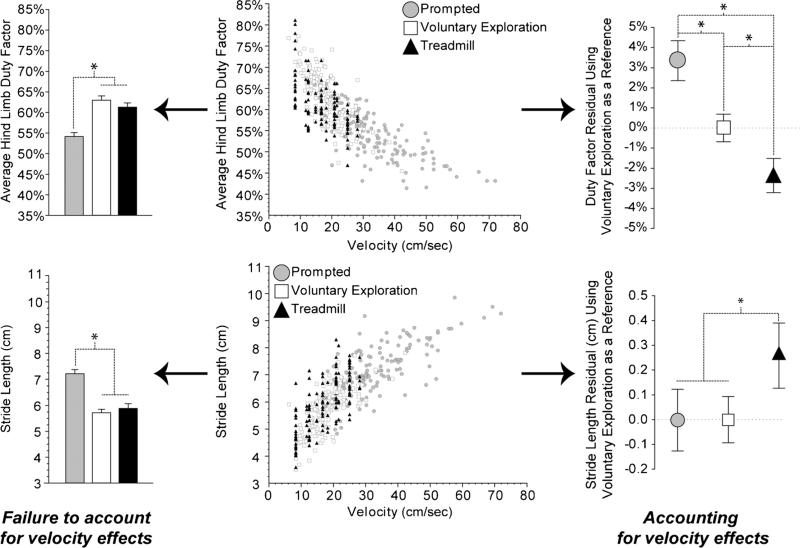

Fig. 3.

The effect of velocity on the spatiotemporal gait characteristics of rodents. The vast majority of gait variables correlate to velocity, and failure to account for velocity effects can significantly affect the statistical analysis of data. Shown are the average hind limb duty factor and stride length for naïve, healthy C57Bl/6 mice (n=25, 5 trials per animal per gait environment). Data were collected at Duke University in 2008–2009 on IACUC-approved protocols with techniques adhering to AAALAC ethical guidelines . The center graphs indicate that both duty factor and stride length have strong correlations to velocity. Statistical analyses ignoring this covariate are shown on the left, whereas statistical analyses that account for velocity are shown on the right. As can be seen from this demonstration, prompted gaits would appear to be very different from those of voluntary exploration or the treadmill if the velocity covariate was ignored, but this difference is largely due to the fact that prompted gaits occurred at higher velocities. If velocity effects are accounted for in the analysis, the stride length is very similar between prompted gait and voluntary exploration, but tends to be slightly longer on treadmills (≈0.3 cm longer at a given velocity). Similarly, duty factor differences among all three groups occur if velocity effects are considered. Here, duty factor tended to be shorter on the treadmill and longer for prompted gaits relative to voluntary exploration. Closer inspection of the raw data reveals a deviation from a linear correlate near duty factors of 50 %. Since a duty factor of less than 50 % would be defined as running, this implies that a transition between walking and running gaits is likely the driver of duty factor differences between voluntary exploration and prompted gaits (walking-to-running transition)