Introduction

Difficulties in recruiting, engaging, and retaining minority participants in prevention strategies are a serious challenge to efforts to reduce health disparities (Yancy, Ortega, & Kumanyika, 2006). Interventions that can successfully access hard-to-reach and socially disadvantaged groups; as well as demonstrate effectiveness, engagement, and adoption by diverse participants are needed (Barrera, Castro, & Steiker, 2011). However, participants may find a program's content, delivery approach, setting, and other factors culturally mismatched (Harachi, Catalano, & Hawkins, 1997; Castro, Barrera, & Martinez, 2004).

Cultural adaptations of health promotion prevention programs modify both surface structures (social and behavioral characteristics) and deep structural levels (worldview, norms, beliefs and values) to promote their acceptance and comprehension (Castro et al., 2004). By becoming linguistically and culturally appropriate, participants are more engaged and satisfied, and better outcomes may be produced (Castro et al., 2004; Solomon, Card, & Malow, 2006; Dillman-Carpentier et al., 2007; Lau, 2006).

Stage models outline steps for cultural adaptation (Barrera, Castro, Strycker, & Toobert, 2012a; Card, Solomon, & Cunningham, 2011; Wingood & DiClemente, 2008), and assist in making systematic decisions on adaptation-related activities (Barrera et al., 2012a). These steps may include: (1) performing literature searches, and collecting data from representative members; (2) integrating findings into the original intervention and translating materials; (3) testing with the cultural group for appropriateness; (4) revising based upon feedback received; and (5) conducting a trial to determine its efficacy (Barrera et al., 2012a).

Missing, however, is the critical step of developing a conceptual framework to guide the process to address the deep structural level. The use of theory has been noted as significant (Castro et al., 2004; Barrera, Castro, Strycker, & Toobert, 2013; Wilson & Miller, 2004), but a lack of guidance exists on how theory can be used to: (1) identify relevant deep structural factors for their influences on behaviors; and (2) explore the relationships of these cultural factors to the original theory of an intervention.

This paper asserts that prior to the cultural adaptation of prevention programs, it is necessary to first develop a conceptual framework. We propose a multi-phase approach to address key challenges in adaptation by first identifying and exploring relevant cultural factors that may affect the targeted health-related behavior before proceeding through a stage model. Phase I develops a conceptual framework for a health promotion prevention program that integrates cultural factors to ground the process. Phase II employs stage model steps. For phase I, we offer four key steps, and use our research study as an example of how these steps were applied to build a framework for the cultural adaptation of a family-based intervention, Guiding Good Choices (GGC) (Hawkins & Catalano, 1987) to Chinese American families. Lastly, we provide a summary of the preliminary evidence from a few key relationships that were tested among our sample with the greater purpose of discussing how these findings might be used to culturally adapt GGC. The aim is to link research to practice to provide strategic and applicable information for professionals engaged in developing culturally responsive health promotion prevention interventions for minority groups.

The conceptual framework guided the research questions asked in the second phase of our proposed multi-phase approach. Data were collected from Chinese American parent-child dyads from three elementary schools in Chicago's Chinatown. To assess the theoretical constructs, scales with strong reliability and validity within similar populations were used. This process set the stage for culturally adapting GGC.

Surface and Deep Structural Levels

Fit of an intervention to the culture can facilitate recruitment of ethnic minorities (Harachi et al., 1997) and other cultural groups (Marek, Brock, & Sullivan, 2006), and encourage their participation (Resnicow, Soler, Braithwaite, Ahluwalia, & Butler, 2000; Castro et al., 2004). Adaptations at a surface level involve knowledge of the social and behavioral characteristics of a behavior among a cultural group to improve its outward appeal. For example, alterations to the language, such as through translation or including vernacular phrases and relevant sounds (e.g. voices, music) may enhance engagement. Surface changes can also occur through the images and visual representations in the program. For example, role models that represent the targeted group can alter the appearance of an intervention and make the program more acceptable. Cultural adaptation may also involve identifying suitable media channels and settings for recruitment (Harachi et al., 1997), and employing racially/ethnically matched staff to administer the program (Resnicow et al., 2000).

Adaptation at the deep structure addresses core values, beliefs, norms, and worldviews of the targeted cultural group to provide context and give saliency to the problem (Resnicow et al., 2000; Castro et al., 2004). Examples of “deep structure” factors are two significant and opposing dimensions of culture, collectivism and individualism (Triandis & Suh, 2002), a source of fundamental differences between two societies by defining the individual's role versus the group's (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, 2010). East Asian countries are largely collectivist, whereas Western societies like the United States are more individualistic (Kagitcibasi, 2005). These dimensions may be especially relevant to immigrant families struggling to meld two cultures (Phalet & Schönpflug, 2001).

Collectivistic cultures emphasize interpersonal and interdependent relationships, and view them as important to sustaining underlying cultural norms, values, and beliefs. Individualistic cultures are concerned with individuality and achieving independence from others (Triandis & Suh, 2002). Shared norms in a group significantly shape behaviors among collectivistic cultures, while attitudes and anticipated consequences from behaviors drive individualists’ actions (Triandis & Suh, 2002).

Key Challenges to Cultural Adaptation

Cultural adaptations encounter challenges to preserving an intervention's effectiveness (Solomon et al., 2006; Castro, Barrera, & Steiker, 2010), and distinguishing and understanding the influences of different cultural factors on the desired outcome to merit their incorporation (Mier, Ory, & Medina, 2010). Firstly, adaptations can inadvertently remove and/or dilute an intervention's core components that are theoretically based, resulting in decreased effectiveness (Solomon et al., 2006; Kumpfer, Alvarado, Smith, & Bellamy, 2002). Castro et al., (2004) calls this the fidelity-adaptation tension issue, which describes a struggle between implementing a universal intervention with fidelity as designed by the developer against adapting it to the cultural context of the local community. For example, Harachi, et al. (1997) found that facilitators for GGC, previously known as Preparing for the Drug Free Years, conducting workshops in Samoan or Spanish failed to incorporate provided videotapes because of their perceptions that participants would not be able to relate to the actors. A review of the effectiveness of adapted versions of Strengthening Families Program to African Americans, Hispanics, Asian Pacific Islanders, and American Indian families revealed that although the culturally adapted versions increased recruitment and engagement, the original intervention resulted in slightly better outcomes. Eliminating core elements of the program were among the researchers’ hypothesized reasons (Kumpfer et al., 2002).

Secondly, Resnicow et al. (2000) argues that while many programs have included culturally-based values, for example, prominence of the family within Hispanic populations, the separate impact of each value on the behavior is unclear because they have seldom been isolated and investigated experimentally. A commonly used method involves making alterations based on the discretion of program facilitators (Harachi, Catalano, Hawkins, 1997; Marek, Brock, and Sullivan, 2006) or gathering qualitative data through focus groups to guide the fit or match to the surface and deep structural roots of a culture (Resnicow et al., 2000; Dumka, Gonzales, Wood, and Formoso, 1998). Focus groups are potentially valuable for developing culturally sensitive messaging for interventions (Resnicow et al., 2000) and in examining the knowledge, beliefs and practices of a phenomenon (Pasick et al., 2009).

Absent from this type of research, however, is incorporating the knowledge gained from cultural experts and inductive research to systematically explore culturally-based constructs existing beyond the conscious awareness of lay participants (Pasick, et al., 2009). Building a conceptual framework first to guide these modifications can address these key challenges. It establishes an intervention's core components; and delineates the culturally-based constructs and their relationships to the behavior so the saliency, strength, and directions of their distinct outcomes among a cultural group can be revealed.

Guiding Good Choices

Guided by the Social Development Model (SDM), GGC addresses risk and protective precursors for preventing alcohol use through developing parenting practices that increase positive parent-child bonding (Kosterman, Hawkins, Haggerty, Spoth, & Redmond, 2001; Catalano, Kosterman, Haggerty, Hawkins, & Spoth, 1998). Developed by J.D. Hawkins and R.F. Catalano (1987), this program targets parents of children between ages 9 and 14. Bonding within the family, proposed by SDM, develops when children are socialized through opportunities, skills, and rewards for involvement. Positive bonding to parents can protect adolescents from alcohol use (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996).

Its five sessions seek to instruct parents on the following practices: (1) create opportunities for involvement and interactions, and reward their children's participation; (2) set clear expectations, monitor behaviors, and practice appropriate discipline; (3) teach children to resist peer pressure to engage in problem behaviors; (4) manage and reduce family conflict; and (5) express positive feelings and love (Kosterman et al., 2001).

Building a Conceptual Framework

We argue that just as it is necessary for interventions to be grounded in theory, a conceptual framework provides the foundation for cultural adaptation of a health promotion prevention program. The overarching or main theory we used to develop our conceptual framework is the Theory of Triadic Influence (TTI) (Flay & Petraitis, 1994).

TTI is a comprehensive macro-level theory that furthermore integrates individual-level theories of health-related behavior, such as the Health Belief Model, Theory of Planned Behavior, and Social Learning Theory. The purpose of this theory in our framework is to identify cultural factors at the deep structural level, which influence family-based risk and protective factors that encourage or prevent adolescent alcohol use. TTI proposes three major streams of influence that flow from the beginning at the deep structural level to the last tier of decision making or intention to perform a behavior. These streams are called cultural environmental, social situational, and intrapersonal influences (Flay & Petraitis, 1994).

The cultural environmental stream provides information that influences the knowledge of and expectations from performing a health-related behavior, as well as transmits broader cultural values to affect attitudes toward that behavior. Social situational addresses the immediate social settings of a behavior. Normative beliefs regarding the behavior of others (e.g. peers and family members), and social motivations to mirror these behaviors are further reinforced through social bonding. Intrapersonal influences include inherited characteristics of a person which shape a sense of self and degree of social competence, and ultimately, determine his/her self-efficacy for performing the behavior (Flay & Petraitis, 1994).

To build the conceptual framework for GGC's cultural adaptation, we explored deep structural factors within TTI's cultural stream. We developed four key steps to build this framework: (1) examine the original theory underlying the intervention to determine the constructs relevant to the program's core components; (2) use a macro-level theory to identify and select key constructs most likely to be culturally dependent; (3) review the literature to specify how culture might influence these constructs; and (4) incorporate culturally-based constructs and their relationships to the core constructs to direct in-depth exploratory research.

Step 1: Examine theory of original intervention to identify core constructs

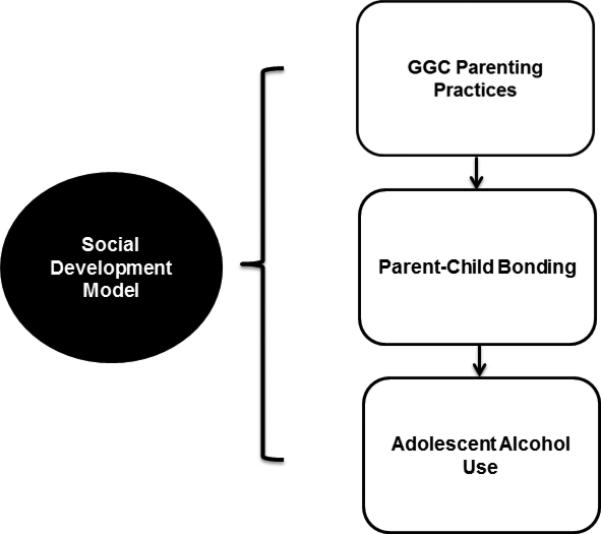

While GGC aims to prevent adolescent alcohol use, the behavior targeted for change is parenting practices. Key constructs of the underlying theory are parenting practices, parent-child bonding, and adolescent alcohol use. Together they serve as the intervention's core components (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Core constructs of original intervention from Social Development Model.

Step 2: Use a macro-level theory to identify and select culturally-based factors

Rather than selecting culturally-based factors without a clear understanding of their relationships to changing a behavior targeted by an intervention, TTI guides the selection of factors that may prove relevant. This in turn guides the research questions to pose to representatives of the cultural group for exploration.

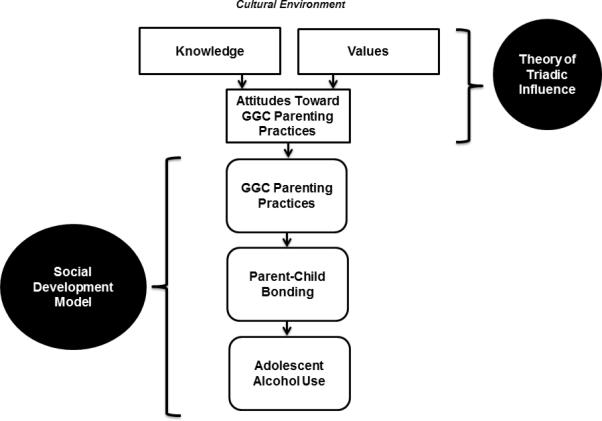

For instance, TTI can identify culturally-based factors at the deep structural level that affect parents’ willingness to employ GGC practices. It takes an ambiguous construct such as culture, and makes possible quantifiable measurement through identifying constructs and delineating their relationships to the behavior. Culture influences knowledge and personal values, which together affect the attitudes toward parenting practices. Attitudes determine the intention to perform the parenting practices, subsequently influencing the parent-child bond. The strength of this bond protects adolescents from alcohol use.

It is possible to empirically measure each component in this model and their relationships to each other: knowledge, values, attitudes toward GGC parenting practices, parent-child bond, and child's risk and behaviors with alcohol. Figure 2 expands the original theory to include constructs through which culture influences the outcome variable, parenting practices.

Figure 2.

Use of a macro-level theory to incorporate culturally-based constructs

Step 3: Review literature on culturally important constructs

Support exists for unique culturally-based processes within this group concerning the parenting practices of this intervention. Literature on Chinese family values, knowledge, and attitudes uncover some key concepts. This step serves the dual purpose of gaining greater information about relevant constructs within the targeted cultural group or a similar population due to limitations in the literature, as well as to identify possible scales that may be appropriate to use to measure these same constructs for testing the conceptual framework. Below contains the findings from our literature review of constructs within the conceptual framework that we had developed so far.

Values

Asian cultural values such as emotional self-control (Kim, Atkinson, & Yang, 1999) may hinder Chinese American parents’ attitudes toward and exercise of GGC parenting practices such as expressing warm approval and affection to their children to foster bonding. Unquestioning authority of elders may make it difficult for Chinese American parents to involve their children in the decision-making around family activities. The Asian Values Scale (AVS) assesses individual adherence to traditional Asian cultural values in broad cultural dimensions (Kim et al., 1999). Conforming to family norms and several others have been found to be positively related to parent-child conflict (Tsai-Chae & Nagata, 2008). Conformity to family norms refers to expectations of children to obey and conform to the family's child- and gender-related roles and obligations. This collectivist value clashes with the predominantly individualistic culture of the United States, and can negatively affect interactions between immigrant parents and their more Western acculturated children (Tsai-Chae & Nagata, 2008).

Knowledge

This construct points to Chinese American parents’ knowledge that specific parenting practices taught by GGC can promote parent-child bonding to prevent adolescent alcohol use. It was hypothesized that the greater the beliefs held among parents about the problem of underage drinking and importance of parent-child bonding, the more willing they would be to learn and employ these practices. Due to limited research regarding both Chinese American parents’ knowledge and performance of GGC parenting practices, we mirrored past research studies (Fleming, Catalano, Oxford, & Harachi, 2002; Deng & Roosa, 2007) whose purpose was to test the generalizability of SDM, the original theory behind the family-based program. We included survey questions that they had developed based upon SDM to assess performance of GGC parenting practices (e.g. providing opportunities for family involvement, giving rewards such as money and privileges, etc.); and measured bonding using questions from these same studies. Lastly, we included several questions to determine degree of awareness of underage drinking.

Attitudes

This refers to attitudes Chinese American parents hold toward GGC's parenting practices, which may also be described as parenting styles as posited by the Contextual Model of Parenting Style (CMPS) (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). CMPS defines parenting style as “a constellation of attitudes toward the child that are communicated to the child and that taken together, create an emotional climate in which the parent's behaviors are expressed” (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Parenting styles can influence the effectiveness of parenting practices to socialize their children. CMPS proposes that a parenting style is shaped by values parents hold and goals parents have for socializing their children, and in turn, influences the parenting practices employed (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). It further posits that parenting practices directly affect a child's developmental outcomes, which is bonding to his/her parent in this context. Parenting styles based upon its definition within CMPS was therefore included to determine its interactions with parenting practices to promote parent-child bonding.

Chao (1994) proposes Chinese-based parenting styles called guan, a Chinese term representing the idea that parents train and direct their children to behave appropriately, and act according to expectations and standards of conduct through teaching and education. Along with the aspect of control by setting expectations, always monitoring and correcting behaviors, guan includes high levels of devotion, involvement, commitment, and sacrifice (Chao, 1994).

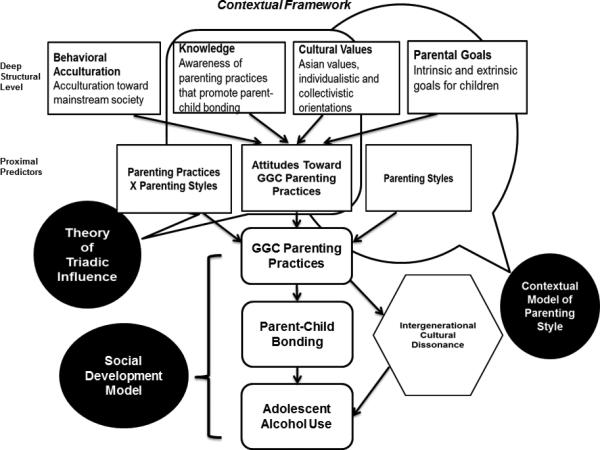

Step 4: Add constructs for in-depth exploration and finalize the conceptual framework

The core theory was expanded by adding several constructs mentioned above, including parental goals. Cultural variables such as intergenerational cultural dissonance (ICD), otherwise referred to here as acculturation-based conflict, were added as well given their relevance to adolescent problem behaviors among Asian American families (Choi, He, & Harachi, 2008).

Acculturation gaps develop over time between parents and children of immigrant families from dissonant acculturation, defined as a pattern of varying rates of assimilation to mainstream society (Portes, 1997). It is a conceptual and empirical way to assess parent-child differing acculturation rates (Lee, Choe, Kim, & Ngo, 2000). After migration, children often embrace the majority culture more rapidly, resulting in an acculturation gap at home (Portes, 1997). This gap can lead to acculturation-based conflict between parents and children over differences in their fidelity to cultural values (Choi, et al., 2008). For example, Tsai-Chae and Nagata (2008) found that among Asian American college students, perceptions that parents more strongly adhered to traditional cultural values predicted parent-child conflict. Moreover, ICD has been found to increase risk for problem behaviors, including alcohol use, among adolescents from immigrant families (Choi et al., 2008; Buchanan & Smokowski, 2009).

ICD was thus added to: (1) determine the association between parenting practices and acculturation-based conflict; and (2) investigate the precursors to adolescent alcohol use among Chinese American families. It allowed for exploration of how bonding between parent and child serves as a protective factor, as well as how ICD acts as a risk factor. Results can inform the cultural adaptation to target both. Additionally, ICD was examined at greater depth to understand how it results from acculturation gaps within Chinese American families. Acculturation was included due to the largely immigrant population under study. Barrera, Toobert, Strycker, & Osuna (2012b) maintain that for cultural adaptations to immigrant populations, exploring acculturation effects is critical.

Lastly, social norms are culturally founded, and may be important to examine (Castro et al., 2004). Norms here are related to the priority group's perceptions of other Chinese parents engaging in parenting practices similar to those taught in GGC in the community. However, actual norms of the community may or may not engage in similar practices so influencing participants’ perceptions would not prove helpful. This presents an important example of including culturally-based constructs that can feasibly be addressed in the adaptation and implementation of the chosen intervention. Figure 3 presents the final conceptual framework.

Figure 3.

Conceptual framework for a deep structural level cultural adaptation of GGC

Summary of Preliminary Evidence of Key Relationships from the Conceptual Framework

We present a summary of preliminary evidence from a few key relationships that were tested from our conceptual framework with the primary purpose of discussing how these findings might be used to culturally adapt GGC. Data were collected from 191 Chinese American parent-child dyads through self-administered questionnaires from students in the 6th through 8th grades and their parents from three elementary schools in Chicago's Chinatown. Nonprobability sampling was chosen for this research study due to the hard-to-reach and unique population targeted.

Bonding and ICD on adolescent alcohol use

Results from this research study revealed that child's perceived degree bonding with his/her parent served as a protective factor against alcohol use among adolescents. Child's perceived level of acculturation-based conflict with his/her parent, on the other hand, was positively associated with risk for alcohol use. ICD is separate and distinct from the normative parent-child conflict that often occurs during adolescence. It may therefore be necessary for a culturally adapted GGC to address this distinct type of conflict, while concurrently encouraging practices for bonding among immigrant families.

GGC parenting practices and ICD

Positive GGC parenting practices were inversely related to ICD, revealing that as parents engaged in these practices to a greater degree, children perceived less acculturation-based conflict. The finding that parenting practices that promote parent-child bonding according to SDM may also decrease ICD within Chinese American families is noteworthy. It indicates that Western-based theories such as SDM may be appropriate to use among racial/ethnic minority and immigrant populations as well.

Interaction of guan and GGC parenting practices

Guan interacted with child's report of parenting practices to increase the effect of parenting practices on reducing acculturation-based conflict. Further research is needed to explore this finding, and to determine the reasons such as potentially positive attitudes held toward guan by Chinese American adolescents or that an aspect of guan encompasses parental warmth. Instructing Chinese American parents on parenting practices that promote parent-child bonding, and recognizing and expanding them to build upon the strength of guan as a protective factor against conflict, may prove an effective and culturally-adapted strategy.

Acculturation gaps and ICD

Acculturation gaps, measured in this study by taking the difference between self-reported scores of acculturation between parent and child within dyads, were positively related to child perceived level of ICD within families. ICD occurred mainly from the differences between parent and child in Chinese-oriented behaviors and collectivistic values. The parent-child acculturation gap toward American-oriented behaviors and individualistic values were not significant in predicting conflict. Adolescents generally scored lower than their parents on both Asian-oriented behaviors and values so that parents may be attempting to socialize and reinforce their children to maintain their cultural and traditional heritage.

Perhaps the threat that parents perceive is not from their children's adoption of Western behaviors and values, but rather it may arise from their children's loss of cultural values, traditional customs and behaviors, and use of their ethnic language from the country of origin. Chuang and Su (2009) hypothesize that as immigrant parents assimilate to the host country, they view the adoption of Western values as necessary for their children to achieve success in school and in the workplace. Consideration of acculturation-based conflict and its sources within immigrant families may be necessary in a culturally-adapted GGC for this population. By culturally adapting GGC to increase Chinese American parents’ awareness of acculturation-based conflict and its sources such as from the perceived threat of their children losing their ethnic culture and heritage, GGC may prove more effective in both engaging Chinese American parents into the program and enhancing their self-efficacy to implement parenting practices that promote bonding.

Discussion

An overarching framework with steps for achieving deep structural changes has been set forward to demonstrate how a macro-level theory can be used to guide consideration of culturally-based constructs for cultural adaptation of an intervention. The four steps discussed was our attempt to demonstrate how we carefully selected culturally-based constructs at the deep structural level. We then tested several key relationships in our conceptual framework. We plan to continue to test other significant relationships, and gather qualitative data to better understand the salient cultural constructs from our findings with Chinese American families.

While we recognize that this is certainly not the only approach to building a conceptual framework, we believe that these steps may be applied to culturally adapt other types of interventions that are theory-based. Other theories or models that consider the cultural context from outside the behavioral sciences, such as cultural value orientations from cross-cultural psychology (Schwartz et al., 2010), may be used and assessed. Appreciating dimensions of culture from the field of organizational cultures such as relationship to authority and approaches to conflict resolution might also prove useful (Hofstede et al., 2010).

Culture is too complex for us to claim that all relevant constructs have been captured entirely in our framework. However, this paper contributes to the literature by making explicit how culturally-based constructs may be incorporated into a family-based program, and by hypothesizing the mechanisms by which they may improve adoption of parenting practices through theory (Barrera et al., 2013). Without directly assessing cultural dimensions, it remains unclear whether culture takes part in shaping health behaviors (Pasick, D'Onofrio, & Otero-Sabogal, 1996). Until theoretically-based and rigorous adaptations are made, gaps remain in the research on the need for culturally-adapted interventions, as well as how a cultural group might be defined for a health promotion prevention program. Moreover, Pasick et al. (2009) argue that individual-level health behavior theories themselves may require adaptation so its constructs achieve greater validity with a given population. This raises the question if a framework is developed first or should adaptation begin by revealing the cultural dimensions of the constructs from an intervention's original theory.

Questions will also remain about the effectiveness of this strategy on health-related outcomes until randomized control trials are conducted to compare culturally adapted versions against original versions (Kumpfer et al., 2002). Debate will continue to weigh the costs and benefits of cultural adaptation against building entirely new and culturally sensitive interventions (Barrera et al., 2011).

Conclusions and Recommendations

Use of a conceptual framework in cultural adaptation may help to select those members of a group most in need, and assist program developers and facilitators to identify components to add or adapt, and those requiring greater emphasis. It may help identify strengths within a culture to build upon, in addition to risk factors. It may move the science forward from adapting programs to specific racial/ethnic populations, and allow for adaptations to focus on commonly shared experiences such as immigration to define a cultural group. Such health promotion prevention interventions are necessary to provide meaningful support to ethnic minority and immigrant families who utilize available services and resources the least (Harachi et al.,1997).

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Jr., Castro FG, Strycker LA, Toobert DJ. Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: A progress report. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(2):196–205. doi: 10.1037/a0027085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Jr., Castro FG, Steiker LKH. A critical analysis of approaches to the development of preventive interventions for subcultural groups. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48:439–454. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9422-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Jr., Toobert D, Strycker L, Osuna D. Effects of acculturation on a culturally adapted diabetes intervention for Latinas. Health Psychology. 2012b;31(1):51–54. doi: 10.1037/a0025205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan RL, Smokowski PR. Pathways from acculturation stress to substance use among Latino adolescents. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:740–762. doi: 10.1080/10826080802544216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card JJ, Solomon J, Cunningham S. How to adapt effective programs for use in new contexts. Health Promotion Practice. 2011;12(1):25–35. doi: 10.1177/1524839909348592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Jr, Martinez CR., Jr. The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: Resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevention Science. 2004;5(1):41–45. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013980.12412.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Jr., Steiker LKH. Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:213–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The Social Development Model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and crime: Current theories. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Kosterman R, Haggerty K, Hawkins JD, Spoth RL. A universal intervention for the prevention of substance abuse: Preparing for the Drug Free Years. In: Ashery RS, Robertson EB, Kumpfer KL, editors. Drug abuse prevention through family interventions (NIDA Research Monograph 177. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Rockville, MD: 1998. pp. 130–159. NIH Publication No. 97–4135. Available [On-line]: www.nida.nih.gov/pdf/monographs/monograph177/download177.html. [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development. 1994;65(4):1111–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, He M, Harachi TW. Intergenerational cultural dissonance, parent-child conflict and bonding, and youth problem behaviors among Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:85–96. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9217-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang SS, Su Y. Do we see eye to eye? Chinese Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting beliefs and values for toddlers in Canada and China. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23(3):331–341. doi: 10.1037/a0016015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113(3):487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Deng S, Roosa MW. Family influences on adolescent delinquent behaviors: Applying the Social Development Model to a Chinese sample. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;40:333–344. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Wood JL, Formoso D. Using qualitative methods to develop contextually relevant measures and preventive interventions: An illustration. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1998;26(4):605–637. doi: 10.1023/a:1022145022830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman-Carpentier FR, Mauricio AM, Gonzales NA, Millsap RE, Meza CM, Dumka LE, Genalo MT. Engaging Mexican origin families in a school-based preventive intervention. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2007;28:521–546. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0110-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Petraitis J. The Theory of Triadic Influence: A new theory of health behavior with implications for preventive interventions. In: Albrecht GS, editor. Advances in medical sociology, Vol. IV: A reconsideration of models of health behavior change. JAI Press; Greenwich, CT: 1994. pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, Catalano RF, Oxford ML, Harachi TW. Test of generalizability of the Social Development Model across gender and income groups with longitudinal data from the elementary school developmental period. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2002;18(4):423–439. [Google Scholar]

- Harachi TW, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. Effective recruitment for parenting programs within ethnic minority communities. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 1997;14(1):23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ, Minkov M. Cultures and organizations: Intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival. McGraw Hill; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF. The Seattle Social Development Project: Progress report on a longitudinal prevention study; Presented at the National Institute on Drug Abuse press seminar; Rockville, MD. 1987, March. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Weis JG. The social development model: An integrated approach to delinquency prevention. Journal of Primary Prevention. 1985;6:73–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01325432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz NK, Champion VL, Strecher VJ. The health belief model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2002. pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kagitcibasi C. Autonomy and relatedness in cultural context: Implications for self and family. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2005;36(4):403–422. [Google Scholar]

- Kim BSK, Atkinson DR, Yang PH. The Asian Values Scale: Development, factor analysis, validation, and reliability. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46(3):342–352. [Google Scholar]

- Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Haggerty KP, Spoth R, Redmond C. Preparing for the Drug Free Years: Session-specific effects of a universal parent-training intervention with rural families. Journal of Drug Education. 2001;31(1):47–68. doi: 10.2190/3KP9-V42V-V38L-6G0Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R, Smith P, Bellamy N. Cultural sensitivity and adaptation in family-based prevention interventions. Prevention Science. 2002;3(3):241–246. doi: 10.1023/a:1019902902119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS. Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Sciences and Practice. 2006;13(4):295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Choe J, Kim G, Ngo V. Construction of the Asian American Family Conflicts Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2000;47:211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Marek LI, Brock DJP, Sullivan R. Cultural adaptations to a family life skills program: Implementation in rural Appalachia. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2006;27(2):113–133. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-0017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mier N, Ory MG, Medina AA. Anatomy of culturally sensitive interventions promoting nutrition and exercise in Hispanics: A critical examination of existing literature. Health Promotion Practice. 2010;11(4):541–554. doi: 10.1177/1524839908328991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ, Burke NJ, Barker JC, Joseph G, Bird JA, Otero-Sabogal R, Tuason N, Stewart SL, Rakowski W, Clark MA, Washington PK, Guerra C. Behavioral theory in a diverse society: Like a compass on Mars. Health Education and Behavior. 2009;36(Suppl. 1):11S–35S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ, D'Onofrio CN, Otero-Sabogal R. Similarities and differences across cultures: Questions to inform a third generation for health promotion research. Health Education Quarterly. 1996;23(Supplement):S142–S161. [Google Scholar]

- Phalet K, Schönpflug U. Intergenerational transmission of collectivism and achievement values in two acculturation contexts: The case of Turkish families in Germany and Turkish and Moroccan families in the Netherlands. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2001;32(2):186–201. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A. Immigration theory for a new century: Some problems and opportunities. International Migration Review. 1997;31(4):799–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Soler R, Braithwaite RL, Ahluwalia JS, Butler J. Cultural sensitivity in substance abuse prevention. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(3):271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Weisskirch RS, Hurley EA, Zamboanga BL, Park IJK, Kim SY, Umaña-Taylor A, et al. Communalism, familism, and filial piety: Are they birds of a collectivist feather? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16(4):548–560. doi: 10.1037/a0021370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon J, Card JJ, Malow RM. Adapting efficacious interventions: Advancing translational research in HIV prevention. Evaluation and the Health Professions. 2006;29:162–194. doi: 10.1177/0163278706287344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, Suh EM. Cultural influences on personality. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:133–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai-Chae AH, Nagata DK. Asian values and perceptions of intergenerational family conflict among Asian American students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14(3):205–214. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BDM, Miller RL. Examining strategies for culturally grounded HIV prevention: A review. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2003;15(2):184–292. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.3.184.23838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The ADAPT-ITT Model: A novel method of adapting evidence-based HIV interventions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;47:S40–S46. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605df1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancy AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annual Review of Public Health. 2006;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]