Figure 1.

Simulation of Ascertainment Bias Due to Year of Onset Windowing

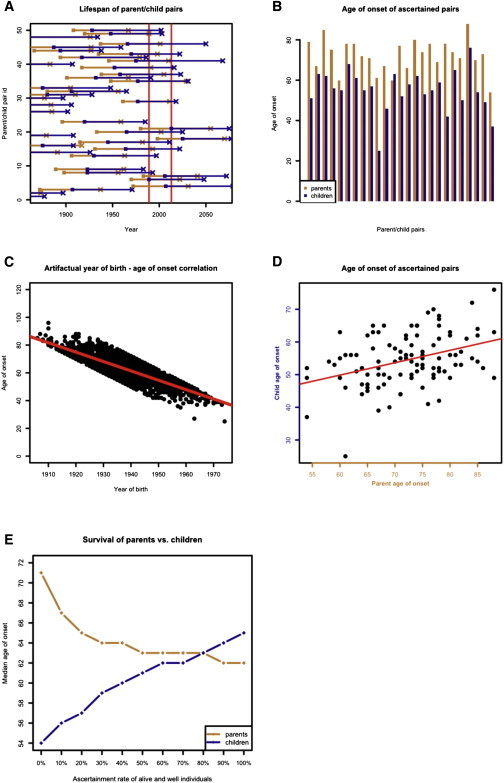

(A) Visual representation of a subset of simulated data. Parent-child pairs are arranged along the y axis. Parent is born on orange square and has disease onset on orange X; child is born on blue square and has disease onset on blue X. Age of onset distributions are identical, but in Simulation 1, only those pairs in which both individuals have onset between 1989 and 2013 inclusive (red vertical lines) can be ascertained. In the above example, only one pair (#49) meets these criteria.

(B) Among ascertained pairs in Simulation 1, children have almost categorically younger onset than their parents, leading to 17 years of observed anticipation (p < 0.0001, two-tailed paired t test). For visibility, a subset of simulated points is shown.

(C) Ascertainment windowing introduces an artifactual correlation between year of birth and age of onset, slope = −0.67 (p < 0.0001, linear regression).

(D) Ascertainment windowing also leads to a correlation between parent and child age of onset and thus a false signal of heritability (slope = 0.48, p < 0.0001, linear regression).

(E) Ascertained pairs are supplemented with those pairs where one individual’s onset occurs in 1989–2013 and the other is alive and well as of 2013. The plot shows that the median survival of parents and children in Kaplan-Meier curves depends upon what proportion of alive and well individuals are included. If 0% are included, then 17 years anticipation are observed, just as in (B). As ascertainment increases, the anticipation is reduced. As inclusion of alive and well individuals approaches 100%, children have longer survival than parents. This is because more of the children are censored, so their age of onset distribution better reflects the hypothetical distribution of age of onset without the influence of competing risks.