Abstract

This work has considered the intrinsic influence of bond energy on the macroscopic, thermodynamic, and mechanical properties of crystalline materials. A general criterion is proposed to evaluate the properties of nanocrystalline materials. The interrelation between the thermodynamic and mechanical properties of nanomaterials is presented and the relationship between the variation of these properties and the size of the nanomaterials is explained. The results of our work agree well with thermodynamics, molecular dynamics simulations, and experimental results. This method is of significance in investigating the size effects of nanomaterials and provides a new approach for studying their thermodynamic and mechanical properties.

Keywords: Size effects, Nanocrystalline materials, Thermodynamic, Mechanical, Bond energy

Background

Nanocrystalline materials exhibit novel physical and chemical properties which are different from the bulk behavior [1-5]. There are a great many theoretical and experimental investigations showing the size-dependent properties of nanomaterials. The typical trend is that the values of the thermodynamic and mechanical parameters fall with decreasing size of nanoparticles and nanostructure. These parameters include melting entropy and melting point [6-15], Debye temperature [10,16,17], cohesive energy [6,18-23], diffusion activation energy [24,25], amplitude of the thermal vibration [26,27], thermal expansion coefficient [28-30], specific heat [31,32], Young’s modulus [33-36], and mass density [37,38]. All these behaviors are generally explained as a result of the high surface-to-volume ratio of nanomaterials. The proportion of atoms at the surface is no longer negligible and they possess higher energies than atoms in the interior of the particle. Over many decades, a huge volume of data has been established by experiments. However, the mechanism of the size effect is not clear because of the variation of these experimental results. Some excellent models have been developed using classical thermodynamics and modern molecular dynamics. However, most of them focus on only one or two parameters and give different explanations. As a result, there is no common understanding of the mechanism of size effects on nanomaterials. In particular, the question of whether it is possible to correlate the variation of the properties of nanomaterials has rarely received attention.

It is well known that the macroscopic thermodynamic and mechanical properties of crystalline materials are intrinsically determined by the binding energy. Therefore, the change of binding energy is the key to explaining the variation of the thermodynamic and mechanical properties of nanomaterials. In this paper, we present a model based on bond energy. By investigating the energy variation of a nanoparticle, an intrinsic interrelation between the thermodynamic and mechanical properties is achieved, revealing the effects of the size of nanocrystalline materials.

Theoretical model

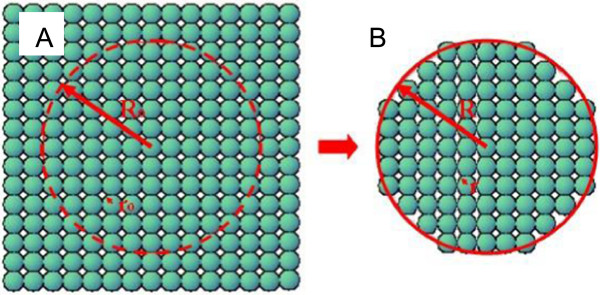

Figure 1 is a physical model used for the description of the energy change of a nanoparticle. In a perfect crystal (Figure 1A), there are no defects and all the atoms are located at their equilibrium lattice positions. The atomic radius is r 0 and the density of the crystal is ρ 0 . A nanoscale spherical particle, with radius R 0 is taken out of the perfect crystal, as shown in Figure 1B. As bond cleavage of surface atoms takes place, the atoms on the outside of the particle depart from their equilibrium positions, resulting in compression of the particle. The radius of the outside particle decreases to R. The average gyration radius is r and the average density is ρ R . Since mass is conserved in the above process, the mass of the sphere in the perfect crystal is equal to the mass of the outside particle. Therefore we have

Figure 1.

A perfect crystal (A) and a nanoparticle taken out of it (B). (A) All the atoms are located at their equilibrium lattice positions. The atomic radius is r0 and the density is ρ0. (B) The particle radius is compressed from R0 to R, the average gyration radius reduces to r, and the average density increases to ρR.

| (1) |

and

| (2) |

where N is the overall number of atoms in the sphere. η is the atomic packing factor and can be determined by calculating the volume of the overall atoms in a unit cell Vatoms, and dividing this by the volume of the unit cell Vcell as follows, . The values of η are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The values of the atomic packing factor ( η) for different crystal structures

| No. | Crystal structure | η (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Body-centered cubic (bcc) |

0.68 |

| 2 |

Face-centered cubic (fcc) |

0.74 |

| 3 |

Close-packed hexagonal (hcp) |

0.74 |

| 4 | Diamond structure (bct) | 0.74 |

In the above process, the energy of the outside particle would increase by an amount ΔW, including the surface energy W1 induced by the bond cleavage of the surface atoms and the lattice distortion energy W2 induced by the compression, due to the surface tension of the outside particle. This is summarized by

| (3) |

According to thermodynamics, the surface energy of the outside particle is equivalent to the increase of the Gibbs free energy. Therefore, the surface energy W1 can be calculated from σ ⋅ ΔS. ΔS is the surface area of the outside particle and σ is the surface tension. That is

| (4) |

In addition, the lattice distortion energy W2 can be calculated by considering the area change of one atom, namely Nσ(4πr02 - 4πr2), where N is the overall number of atoms in the particle. This can be expressed by

| (5) |

Combining Equations 4 and 5, Equation 3 becomes

| (6) |

where W0 is defined as W0 = N ⋅ σ ⋅ 4 ⋅ π ⋅ r02, referring to the overall bond energy or the standard cohesive energy of the spherical particle in the perfect crystal.

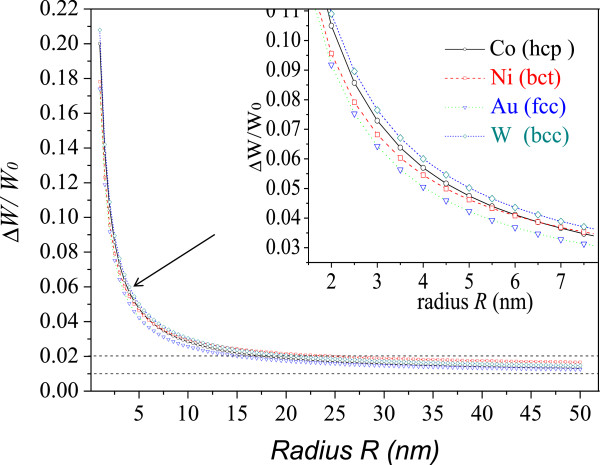

We define the term ΔW/W0 in Equation 6 as the energy variation rate of a nanoscale system. Thus, Equation 6 represents a size-dependent expression of the energy of the nanoparticle. Because ΔW/W0 is based on the bond energy, which intrinsically influences the macroscopic thermodynamic and mechanical properties of crystal materials, it is reasonable that ΔW/W0 is used as a general criterion to evaluate the properties of nanomaterials and to predict all those parameters related to bond energy.From Equation 6, it is clear that the energy is in inverse proportion to the radius of the spherical particle. Figure 2 plots the energy of Au, Co, W, and Ni as a function of the radius of the spherical particles. In each case, the rate of change of the energy gradually increases as the radius decreases, for radii greater than 15 nm. When the radius is around 5 to 15 nm, the rate of change of energy apparently increases with the decrease of the radius, being around 2.2% for Co, 2.43% for Ni, 2.03% for Au, and 2.39% for W, respectively, for radii around 15 nm. Sharp increases occur for radii less than 5 nm. The rates of change of energy for Co, Ni, Au, and W are 10.5%, 9.56%, 9.18%, and 10.9%, respectively, for radii around 2 nm.

Figure 2.

The change of energy of Co, Ni, Au, and W as a function of the radius of spherical particles. (r0Co = 0.1253 nm, σCo = 1.889 N/m; r0Ni = 0.1246 nm, σNi = 1.823 N/m; r0Au = 0.1442 nm, σAu = 1.331 N/m; r0W = 0.1370 nm, σW = 2.534 N/m [39,40]).

Based on the principle of conservation of energy, the change of energy of the spherical particle is equal to the increase of the Gibbs free energy and the decrease of the cohesive energy when the spherical particle is removed from the perfect crystal. Therefore Equation 6 can be written as

| (7) |

where ΔE and E0 are the variational and standard cohesive energy of the nanomaterial, respectively. ΔG and G0 are the variational and standard Gibbs free energy, respectively, for a given value of Δ.

By using thermodynamic investigations, molecular dynamics simulations, and experimental methods, considerable research has been carried out in order to investigate the thermodynamic and mechanical properties of nanomaterials. There is much evidence to suggest that some parameters, such as melting point T m , diffusion activation energy Q d , heat of sublimation L s , square Debye temperature Θ D , and Young’s modulus Y, can be regarded as being directly proportional to the cohesive energy [1,6,8-30]. Heat capacity 1/C m is proportional to square Debye temperature Θ D [10]. It is well known that all these properties of crystalline materials are related to the bond energy. Therefore, a general expression can be used to describe the interrelation of the thermodynamic and mechanical parameters of nanomaterials, as follows:

| (8) |

Combining Equations 7 and 8, this general expression can be simplified to give

| (9) |

where, ΔX and X0 are the variational and standard thermodynamic and mechanical parameters, as determined by the bond energy, respectively.

Discussion

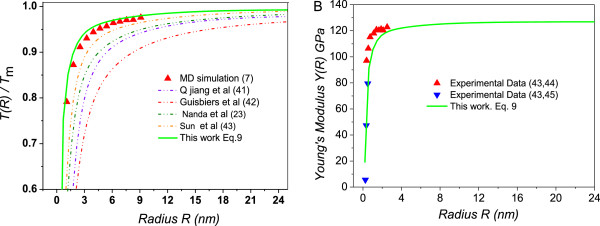

In Figure 3A, our model (Equation 9) is compared to the result of a molecular dynamics simulation and other models, illustrated using the melting points of copper (Cu) nanoparticles. The best agreement is obtained between our model and the results of molecular dynamics simulation, as the particle radius is increased from 1.08 to 9.10 nm. Other models apparently underestimate the melting points of the copper nanoparticles. The ratio of T(R)/T m in our model is slightly higher than the molecular dynamics simulation results, where the size-dependent melting points are lower than those of the experimental data [7]. Figure 3B shows a comparison of the Young’s modulus of copper nanoparticles obtained using Equation 9, with experimental results. Our model predicts the experimental data quite well.

Figure 3.

Size dependence of (A) melting points T( R )/Tm and (B) Young’s modulus for Cu nanoparticles. (A) The solid lines denote predictions from our model of T(R)/Tm in terms of Equation 9, while the black triangles show the molecular dynamics simulation data. Other models [41-43] are also plotted for comparison. (B) Agreement between predictions (solid lines) and experimental observations of the size dependence of the Young’s modulus for Cu particles [43-45]. Parameters are given as r0Cu = 0.1228 nm, σCu = 1.534 N/m, YCu = 128 GPa [39,40].

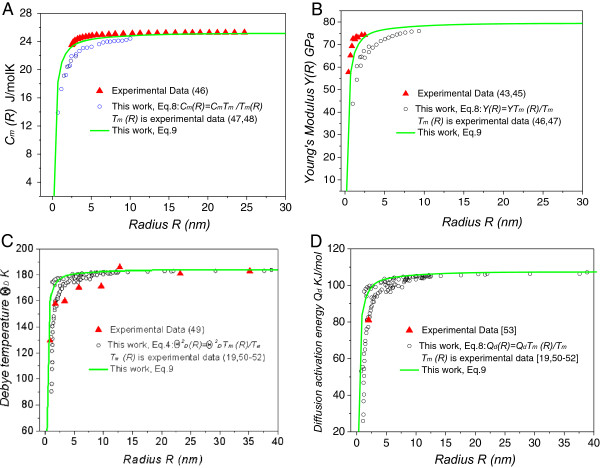

Equations 8 and 9 reveal the essential relationships between the thermodynamic and mechanical properties of nanomaterials. With Equation 8, we can calculate the thermodynamic and mechanical parameters of nanomaterials using data obtained from either experiments or thermodynamic models. The size dependence of the heat capacity C m and Young’s modulus Y for Ag, the Debye temperature Θ D and diffusion activation energy Q d for Au, calculated from Equation 8 using experimental melting point data T m , are plotted in Figure 4. The prediction of our model (Equation 9) and the experimental results are also plotted for comparison. Good agreement is obtained between them.

Figure 4.

Effects of size on the mechanical and thermodynamic properties of nanocrystalline materials. Size dependence of (A) heat capacity Cm[46-48] and (B) Young’s modulus Y for Ag [43,45-47], (C) Debye temperature ΘD, [49,19-52] and (D) diffusion activation energy Qd for Au [53,19,50-52]. Solid lines refer to parameters calculated from Equation 9 (our model prediction). The white circle is plotted using Equation 4 and experimental data for the melting points Tm. The solid triangles show the experimental data (r0Ag = 0.1444 nm, σAg = 1.998 N/m, CmAg = 25.36 J/mol · K, YAg = 80 GPa; r0Au = 0.1442 nm, σAu = 1.331 N/m, ΘDAu = 184.59 K, QdAu = 108 KJ/mol [39,40,48,54]).

Conclusions

In summary, we have demonstrated the intrinsic interrelations between the thermodynamic and mechanical properties of nanomaterials using our bond energy model and previous results to characterize aspects of the size effects on nanocrystalline materials. Equation 9 not only presents a new model to better describe the thermodynamic and mechanical properties of nanomaterials, but also provides a new approach to obtain these parameters from others without requiring the formulation and proof of new models. In other words, most of the thermodynamic and mechanical properties of nanomaterials can be predicted by using either experimental data or results of a theoretical analysis. In this way, all factors, such as shape, crystal structure, defects and fabrication processes of nanomaterials, which must be considered when predicting the physical parameters of nanomaterials, can be obtained from experimental data. This is a significant advancement in the investigation and application of nanomaterials.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

XH proposed the theoretical conception and drafted the manuscript. ZL participated in the theoretical design and helped to draft the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Xiaohua Yu, Email: xiaohua_y@163.com.

Zhaolin Zhan, Email: zl_zhan@sohu.com.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 51165016).

References

- Gleite H. Nanocrystalline materials. Prog Mater Sci. 1989;33:223–315. doi: 10.1016/0079-6425(89)90001-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein AS, Murday JS, Rath BB. Challenges in nanomaterials design. Prog Mater Sci. 1997;42:5–21. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6425(97)00005-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giebultowicz T. Nanothermodynamics: breathing life into an old model. Nature. 2000;408:299–301. doi: 10.1038/35042654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong WP, Tao NR, Wang ZB, Lu J, Lu K. Nitriding iron at lower temperatures. Science. 2003;299:686–688. doi: 10.1126/science.1080216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers MA, Mishra A, Benson DJ. Mechanical properties of nanocrystalline materials. Prog Mater Sci. 2006;51:427–556. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2005.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun CQ, Wang Y, Tay BK, Li S, Huang H, Zhang YB. Correlation between the melting point of a nanosolid and the cohesive energy of a surface atom. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:10701–10705. doi: 10.1021/jp025868l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delogu F. Structural and energetic properties of unsupported Cu nanoparticles from room temperature to the melting point: molecular dynamics simulations. Phys Rev B. 2005;72:205418. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Li JC, Jiang Q. Size effect on the freezing temperature of lead particles. J Mater Sci Lett. 2000;19:1893–1895. doi: 10.1023/A:1006778426038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guisbiers G, Buchaillot L. Modeling the melting enthalpy of nanomaterials. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:3566–3568. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YF, Lian JS, Jiang Q. Modeling of the melting point, Debye temperature, thermal expansion coefficient, and the specific heat of nanostructured materials. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:16896–16900. doi: 10.1021/jp902097f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li YJ, Qi WH, Huang BY, Wang MP, Xiong SY. Modeling the thermodynamic properties of bimetallic nanosolids. J Phys Chem Solids. 2010;71:810–817. doi: 10.1016/j.jpcs.2010.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guisbiers G, Buchaillot L. Universal size/shape-dependent law for characteristic temperatures. Phys Lett A. 2009;374:305–308. doi: 10.1016/j.physleta.2009.10.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guisbiers G. Size-dependent materials properties towards a universal equation. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2010;5:1132–1136. doi: 10.1007/s11671-010-9614-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guisbiers G. Review on the analytical models describing melting at the nanoscale. J Nanoscience Lett. 2012;2:8. doi: 10.4236/snl.2012.21002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli D. Size effect in melting: a historical overview. T Indian Ceramsoc. 2008;67:49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sadaiyandi K. Size dependent Debye temperature and mean square displacements of nanocrystalline Au, Ag and Al. Mater Chem Phys. 2009;115:703–706. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2009.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jasiukiewicza C, Karpusb V. Debye temperature of cubic crystals. Solid State Commun. 2003;128:167–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ssc.2003.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qi WH, Wang MP, Xu GY. The particle size dependence of cohesive energy of metallic nanoparticles. Chem Phys Lett. 2003;372:632–634. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2614(03)00470-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Safaei A. Shape, structural, and energetic effects on the cohesive energy and melting point of nanocrystals. J Phys Chem C. 2010;114:13482–13496. doi: 10.1021/jp1037365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Li JC, Chi BQ. Size-dependent cohesive energy of nanocrystals. Chem Phys Lett. 2002;366:551–554. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2614(02)01641-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CC, Li S. Investigation of cohesive energy effects on size-dependent physical and chemical properties of nanocrystals. Phys Rev B. 2007;75:165413. [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Liu D, Zheng WT, Jiang Q. Size and structural dependence of cohesive energy in Cu. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112:18840–18845. doi: 10.1021/jp7114143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vanithakumari SC, Nanda KK. A universal relation for the cohesive energy of nanoparticles. Phys Lett A. 2008;372:6930–6934. doi: 10.1016/j.physleta.2008.09.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo WH, Deng L, Su KL, Li KM, Liao GH, Xiao SF. Gibbs free energy approach to calculate the thermodynamic properties of copper nanocrystals. Phys B. 2011;406:859–863. doi: 10.1016/j.physb.2010.12.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu XH, Zhan ZL, Rong J, Liu Z, Li L, Liu JX. Vacancy formation energy and size effects. Chem Phys Lett. 2014;600:43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hou M, Azzaoui ME, Pattyn H, Verheyden J, Koops G, Zhang G. Growth and lattice dynamics of Co nanoparticles embedded in Ag: a combined molecular-dynamics simulation and Mössbauer study. Phys Rev B. 2000;62:5117–5128. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.62.5117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Ao ZM, Zheng WT. Temperature and size effects on the amplitude of atomic vibration of Co nanocrystals embedded in Ag matrix. Chem Phys Lett. 2007;439:102–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2007.03.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gleiter H. Nanostructured materials: basic concepts and microstructure. Acta Mater. 2000;48:1–29. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6454(99)00285-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YH, Lu K. Grain-size dependence of thermal properties of nanocrystalline elemental selenium studied by X-ray diffraction. Phys Rev B. 1997;56:14330–14337. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.56.14330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CC, Xiao MX, Li W, Jiang Q. Size effects on Debye temperature, Einstein temperature, and volume thermal expansion coefficient of nanocrystals. Solid State Commun. 2006;139:148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ssc.2006.05.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp J, Birringer R. Enhanced specific-heat-capacity (cp) measurements (150–300 K) of nanometer-sized crystalline materials. Phys Rev B. 1987;36:7888–7890. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.36.7888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstern E, Fecht HJ, Fu Z, Johnson WL. Structural and thermodynamic properties of heavily mechanically deformed Ru and AlRu. J Appl Phys. 1989;65:305–310. doi: 10.1063/1.342541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas M, Mai W, Yang R, Wang ZL, Riedo E. Aspect ratio dependence of the elastic properties of ZnO nanobelts. Nano Lett. 2007;7:1314–1317. doi: 10.1021/nl070310g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni AJ, Zhou M, Ke FJ. Orientation and size dependence of the elastic properties of zinc oxide nanobelts. Nanotechnology. 2005;16:2749–2756. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/16/12/001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LX, Huang HC. Young’s moduli of ZnO nanoplates: ab initio determinations. Appl Phys Lett. 2006;89:183111. doi: 10.1063/1.2374856. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RE, Shenoy VB. Size-dependent elastic properties of nanosized structural elements. Nanotechnology. 2000;11:139–147. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/11/3/301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Safaei A. Size-dependent mass density of nanocrystals. Nano. 2012;71:250009. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda KK. Size-dependent density of nanoparticles and nanostructured materials. Phys Lett A. 2012;376:3301–3302. doi: 10.1016/j.physleta.2012.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warlimont M. Springer Handbook of Condensed Matter and Materials Data. New York: Spinger Berlin Heidelberg; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Keene BJ. Review of data for the surface tension of pure metals. Int Mater Views. 1993;38:157–192. [Google Scholar]

- Jing Q, Yang CC. Size effect on the phase stability of nanostructures. Curr Nanoscience. 2008;4:179–200. doi: 10.2174/157341308784340949. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guisbiers G, Kazan M, Overschelde OV, Wautelet M, Pereira S. Mechanical and thermal properties of metallic and semiconductive nanostructures. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112:4097–4103. doi: 10.1021/jp077371n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun CQ, Tay BK, Zeng XT, Li S, Chen TP, Zhou J, Bai HL, Jiang EY. Bond-order–bond-length–bond-strength (bond-OLS) correlation mechanism for the shape-and-size dependence of a nanosolid. J Phys Cond Matter. 2002;14:7781–7795. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/14/34/301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Streitz FH, Cammarata RC, Sieradzki K. Surface-stress effects on elastic properties. I. Thin metal films. Phys Rev B. 1994;49:10699–10706. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.49.10699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong EW, Sheehan PE, Lieber CM. Nanobeam mechanics: elasticity, strength, and toughness of nanorods and nanotubes. Science. 1997;277:1971–1975. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.1971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong SY, Qi WH, Cheng YJ, Huang BY, Wang MP, Li YJ. Universal relation for size dependent thermodynamic properties of metallic nanoparticles. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13:10652–10660. doi: 10.1039/c0cp90161j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao SF, Hu WY, Yang JY. Melting temperature: from nanocrystalline to amorphous. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:184504. doi: 10.1063/1.2371112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo WH, Hu WY, Xiao SF. Size Effect on the thermodynamic properties of silver nanoparticles. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112:2359–2369. doi: 10.1021/jp0770155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kästle G, Boyen HG, Schröder A, Plettl A, Ziemann P. Size effect of the resistivity of thin epitaxial gold films. Phys Rev B. 2004;70:165414. [Google Scholar]

- Buffat P, Borel JP. Size effect on the melting temperature of gold particles. Phys Rev A. 1976;13:2287–2298. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.13.2287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dick K, Dhanasekaran T, Zhang ZY, Meisel D. Size-dependent melting of silica-encapsulated gold nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2312–2317. doi: 10.1021/ja017281a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambles JR. An electron microscope study of evaporating gold particles: the Kelvin equation for liquid and the lowering of the melting point of solid gold particles. Proc R Soc London A. 1971;324:339–351. doi: 10.1098/rspa.1971.0143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata T, Bunker BA, Zhang ZY, Meisel D, Vardeman CF, Gezelter JD. Size-dependent spontaneous alloying of Au-Ag nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:11989–11996. doi: 10.1021/ja026764r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edalati K, Horita Z. Correlations between hardness and atomic bond parameters of pure metals and semi-metals after processing by high-pressure torsion. Scr Mater. 2011;64:161–164. doi: 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2010.09.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]