Abstract

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is an inflammatory, usually monophasic, immune mediate, demyelinating disease of the central nervous system which involves the white matter. ADEM is more frequent in children and usually occurs after viral infections, but may follow vaccinations, bacterial infections, or may occur without previous events. Only 5% of cases of ADEM are preceded by vaccination within one month prior to symptoms onset.

The diagnosis of ADEM requires both multifocal involvement and encephalopathy and specific demyelinating lesions of white matter.

Overall prognosis of ADEM patients is often favorable, with full recovery reported in 23% to 100% of patients from pediatric cohorts, and more severe outcome in adult patients.

We describe the first case of ADEM occurred few days after administration of virosomal seasonal influenza vaccine. The patient, a 59-year-old caucasic man with unremarkable past medical history presented at admission decreased alertness, 10 days after flu vaccination. During the 2 days following hospitalization, his clinical conditions deteriorated with drowsiness and fever until coma. The magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed multiple and symmetrical white matter lesions in both cerebellar and cerebral hemispheres, suggesting demyelinating disease with inflammatory activity, compatible with ADEM.

The patient was treated with high dose of steroids and intravenous immunoglobulin with relevant sequelae and severe neurological outcomes.

Keywords: acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, ADEM, influenza vaccination, adverse event, virosomal vaccine

Introduction

Influenza, commonly known as “the flu,” is one of the most relevant infectious diseases worldwide, resulting in about 3 to 5 million cases of severe illness, and about 250 000 to 500 000 deaths every year.1 The etiological agents of influenza are RNA viruses belonging to the family Orthomyxoviridae. The influenza viruses evolve continuously with new strains rapidly replacing the previous ones through both the accumulation of mutations within the genes coding for the surface glycoproteins hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, a phenomenon known as antigenic drift, and the re-assortment of genome segments between viruses.2 In particular, antigenic drift causes the constant and gradual evolution of the viruses resulting in seasonal influenza epidemics.

Annual vaccination is universally considered as the primary tool for control and protection against seasonal influenza.3,4 Currently, most of the vaccines against seasonal influenza used worldwide are inactivated, trivalent, intramuscular injected vaccines. The efficacy of these preparations against influenza symptoms in healthy adults varies between 44–73% depending on the grade of match between circulating and vaccine strains.4,5 Moreover, the efficacy of current inactivated influenza vaccines is lower within elderly, ranging between 17 and 53% depending on the viruses circulating in the community;6 because of this reason, a strategy to enhance the immunogenicity of inactivated vaccines have been investigated. Influenza virosomes are an efficient antigen carrier and adjuvant system: this technology enhances antigen presentation thus inducing both B- and T-cell responses and stimulating a broader immune response.7 Inflexal V® (Berna-Crucell) is a virosomal, subunit vaccine licensed in Italy since 1997 for all subjects aged ≥6 mo.

The virosomal influenza vaccines have been demonstrated safe and well tolerated both in children and adults.7 The common adverse events that have been reported following the administration of these vaccines include local reactions, as local pain, erythema, swelling, and systemic reactions, as fever, headache, sweating, myalgia, and asthenia.7 Most adverse reactions are mild and transient, disappearing spontaneously within 24–28 h without medical treatment. Severe neurological adverse events following the administration of virosomal influenza vaccines have been reported very rarely both in clinical trials and during the large post-marketing surveillance.7

Patient Presentation

A 59-y-old caucasic male was admitted to the emergency department of the and I.R.C.C.S. University Hospital San Martino—IST National Institute for Cancer Research, Genoa, Italy, in December 2011, for decreased alertness. On admission, he was partially oriented, with increased latency in responses and slowed mental processes. On neurological examination, strength and sensibility were normal, deep tendon reflexes were normally evoked and meningeal signs were absent. The patient did not report headache, nausea, or fever, but only of severe asthenia. His past medical history and recent anamnesis were unremarkable.

Ten days before the onset of neurological symptoms, the patient received one shot of virosomal influenza vaccine (Inflexal V®, Berna-Crucell) containing, according to World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations, 15 μg of hemagglutinin per viral strains A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)-like, A/Perth/16/2009 (H3N2)-like, and B/Brisbane/60/2008/like. During the last 10 y the patient usually received seasonal influenza immunization, but precise information on the specific type of vaccination administrated, were unavailable. The patient did not usually take any medication and, in particular, he did not report the administration of any drug in the days before the onset of neurological symptoms.

A cerebral CT (CT) scan performed at admittance was unremarkable. Routine blood tests were also normal. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis performed the day after, showed 32 leukocytes/mm3 (mainly lymphocytes), normal protein and glucose levels, and no oligoclonal bands.

On the basis of the clinical picture, a presumptive diagnosis of infectious meningoencephalitis was made and empirical broad spectrum antiviral and antibacterial therapies with intravenous acyclovir and cephalosporin (ceftriaxone 2 g/day intravenous) were prescribed for 1 wk.

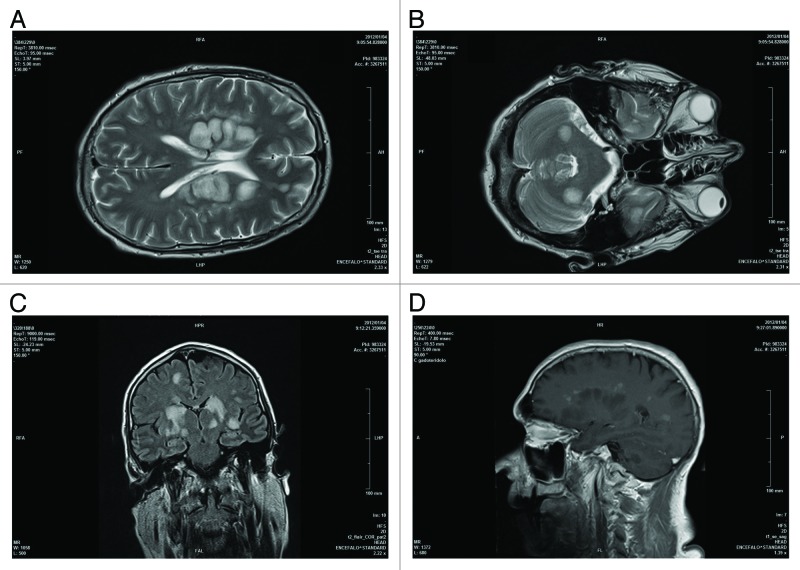

During the first 2 d following hospitalization, the patient’s clinical conditions deteriorated with drowsiness and fever until coma. The first magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed multiple and symmetrical white matter lesions, hyperintense in FLAIR, T2, and DWI sequences, in both cerebellar and cerebral hemispheres, with positive contrast enhancement, suggesting active demyelinating lesions (Fig. 1). Further tests performed on the CSF, including PCR for neurotropic viruses (herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus, JC virus, and cytomegalovirus), tuberculosis test, and research for fungal and bacterial antigens resulted negative. On the basis of the results of MRI and CSF analysis, suggesting an inflammatory immune-mediated disease, the patient started high dose of intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g/day for several days); however, 1 wk after admittance, his conditions suddenly worsened and he was emergently intubated and transferred to intensive care unit (ICU). At admittance in ICU, the patient was in coma state (Glasgow Coma Scale = 4/15), with decerebrate rigidity (also evoked by slight stimulations), deep hyperreflexia, bilateral Babinski sign and divergent deviation of eyes with miotic pupils. A 5-d course of intravenous immunoglobulin was administrated with clinical stabilization of the patient. After 3 wk the patient received a second course of intravenous immunoglobulin, while oral prednisone was gradually tapered, without further modification of the clinical status.

Figure 1. Axial T2 encephalic magnetic resonance (A and B), coronal FLAIR (C), and sagittal T1 post Gd (D) sequences demonstrated: multiple white matter focal lesions located in cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres, predominantly symmetric and cortico-medullary. These lesions are hyperintense on FLAIR, DWI sequences (some of them with increased ADC) with contrast enhancement of larger lesions.

A second CSF analysis was performed 24 d after admittance, during the hospitalization in ICU, showing 0.3 leukocytes/mm3, without further variations compared with the previous exam. The presence of antibodies against influenza viruses (A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and B), both in serum and in CSF, was also tested, with positive results only in serum. During the hospitalization, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, bladder catheter, tracheostomy, central venous catheter were placed, and the patient was treated with antibiotics for healthcare-associated infections.

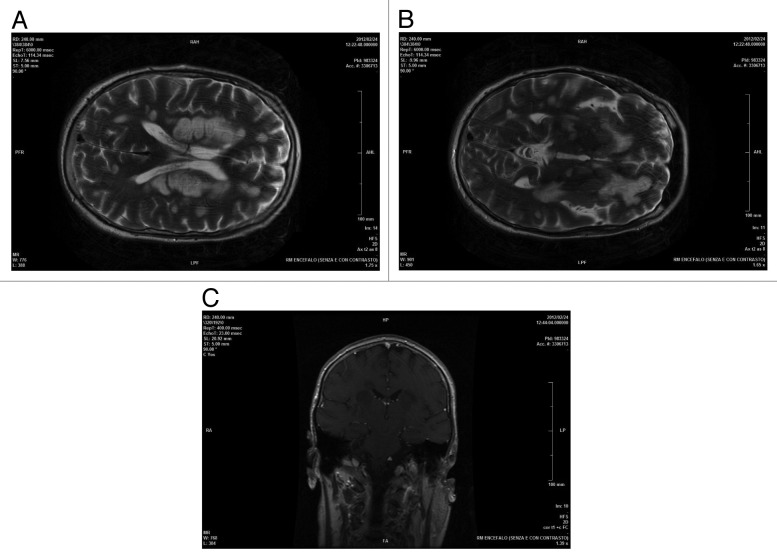

Control brain MRI, 1 mo after the clinical onset, showed a decrease of contrast enhancement., while the extension of the demyelinating lesions was unchanged (Fig. 2). He was extubated at the end of January 2012, but remained unconscious.

Figure 2. AxialT2encephalic magnetic resonance (A and B), coronal T1 post Gd (C) sequences performed about 1 mo after clinical onset of symptoms and after therapy: supratentorial and infratentorial demyelinating lesions were unchanged with overall dimensions slightly reduced and negative enhancement.

At discharge from Neurological Department after 90 d from admission, when the patient was transferred to Rehabilitation Department for Severe Brain Injuries, he was in persistent coma state with no purposeful responses to stimuli, miotic reactive pupils, and flaccid areflexic tetraplegia due to a superimposed critical illness polyneuropathy, demonstrated with electroneurografric examinations.

After 1 y from the onset of the neurological disease, the neurological condition of the patient partially improved; he was able to open his eyes in response to pain and sometimes in response to voice, without any verbal response to stimuli, while flaccid tetraplegia persisted. There was no further relapse of neurological symptoms in this time interval.

The presence of multifocal findings referable to central nervous system, MRI findings displaying diffuse or multifocal white matter lesions and the monophasic pattern to illness suggested a pattern of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) with level 1 of diagnostic certainty according to Brighton Collaboration.8 The onset of the neurological presentation with a plausible time-relationship to influenza vaccination, together with the absence of any other concurrent disease or risk-factor, including drugs assumption and chemicals exposure, suggested a “very likely/certain” causality relationship with the administration of vaccine according to WHO causality assessment criteria for adverse events following immunization.9

Discussion

ADEM is an inflammatory, monophasic, immune mediate, demyelinating disease of the central nervous system.10 The highest incidence of ADEM is observed during childhood, with an annual rate of 0.8 per 100 000, and decreases in young and elderly adults.11 Most cases of ADEM occur after bacterial or viral infectious diseases but approximately 5% of cases of ADEM are preceded by the administration of vaccines (inactivated or live vaccine) within 1 mo prior to symptom onset, thus representing a rare, but severe complication of vaccinations.12

In particular, post vaccination ADEM has been repeatedly reported in association with several vaccines, including those against rabies, diphtheria-tetanus-polio, smallpox, measles-mumps-rubella (live formulation), Japanese B encephalitis.13 Incidence rate of post-vaccination ADEM was estimated to 0.1–0.2/100 000 vaccinated individuals.11

Only few cases of ADEM following parenteral or intranasal seasonal influenza vaccination have been reported in the literature. A review has identified 15 case reports of ADEM occurred in patients ranging from 2 to 64 y following seasonal influenza vaccination since 1982, reporting that patients usually presented neurological symptoms within 3 wk of vaccination and most of them had a complete recovery. Three patients received trivalent not-adjuvanted inactivated influenza vaccination, while in other reports the type of vaccine was not reported.13 Recently, the case of an elderly woman with ADEM, completely recovered after plasma exchange, was reported 8 d after the administration of an inactivated seasonal influenza vaccine.14 Since the limited number of cases, no large population studies on ADEM following seasonal influenza vaccine or estimated incidence rates reporting have been published. Post-marketing surveillance of the Japanese Kitasato Institute reported 3 cases of ADEM among 38.02 million doses of influenza vaccine, with an estimated incidence of approximately 1 in 10 million doses.15

More data are available from the surveillance of adverse events following vaccination with monovalent A/H1N1 pandemic influenza formulations. The results of passive surveillance in China, where 89.6 million doses of non-adjuvant split-virion A/H1N1 pandemic influenza vaccines were administered, reported 2 cases of ADEM corresponding to a reporting rate of 0.02 cases/1 million doses of vaccine administered.16 The European post-marketing safety surveillance system (EudraVigilance) reported 10 cases of ADEM following administration of A/H1N1 monovalent influenza pandemic vaccines notified between October 2009 and December 2010. Seven and three cases occurred following vaccination with adjuvanted and non-adjuvanted formulation, respectively.17 During the time period from 2009 to March 2010, 8 ADEM reports following immunization with H1N1 monovalent influenza vaccine were referred to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the United States national spontaneous vaccine safety surveillance system. According to WHO causality assessment criteria, 4 out of the 8 notified cases were possibly related to immunization by the Center for Disease Control and prevention (CDC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) physicians.18

In this report, we have described a patient affected with ADEM occurred 10 d after the administration of a seasonal trivalent virosomal subunit influenza vaccine: to the best of our knowledge, this is the first case following the administration of this formulation of influenza vaccine.

The clinical presentation and neuroimaging findings fulfilled published criteria for level 1 of diagnostic certainty of ADEM according to Brighton Collaboration.8 Furthermore, the plausible time relationship of the clinical event with the administration of the vaccine, in the absence of other possible etiology, make “very likely/certain” the causality relation according to WHO criteria.9

Based on the presumed autoimmune etiology, the first line treatment for the acute phase is high dose intravenous methylprednisolone (maximum 1 g/day) for 3–5 d, followed by oral corticosteroid tapering of 4 to 6 wk (level IV evidence); in case of insufficient response or contraindication to corticosteroids, the therapeutic option is intravenous immunoglobulin (class IV evidence). According to this evidence, we treated our patient with high dose of steroids and intravenous immunoglobulin.19

Prognosis of ADEM is often favorable. Full recovery is reported in 50% to 75% of the patients and the mean time to recovery ranges from 1 and 6 mo.11 Some studies have associated an unfavorable prognosis to a sudden onset, an unusually high severity of the neurological symptoms, unresponsiveness to steroid treatment, older age, and female gender.11 Our patient had an unfavorable outcomes with severe neurological sequelae and minimal improvement after 1 y.

The pathogenesis of ADEM following administration of inactivated vaccines remains unclear. Different pathological mechanisms have been proposed, including a direct damage of myelin membranes from vaccine-derived products, an immune response to vaccine antigens that cross-reacts with central nervous system myelin proteins (molecular mimicry) resulting in a distant autoimmune reaction, and the unbalance of immune-regulatory mechanisms, due to immunization, that interferes with self-tolerance of host myelin proteins.8

In conclusion, we illustrate a very rare case of ADEM with severe neurological outcome following the administration of a virosomal seasonal influenza vaccine in a subject without any relevant clinical condition before immunization. Despite the rare occurrence of this neurological complication after influenza vaccination, physicians should be aware of the rare possibility of this adverse event.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Acknowledgments

The work was not funded.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ADEM

acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

- CT

computed tomography

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- ICU

intensive care unit

- WHO

World Health Organization

- VAERS

Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System

- CDC

Center for Disease Control and prevention

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

References

- 1.World Health Organization: Fact sheet Number 211 Influenza [Internet]; updated March 2014. Available from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs211.

- 2.Rambaut A, Pybus OG, Nelson MI, Viboud C, Taubenberger JK, Holmes EC. The genomic and epidemiological dynamics of human influenza A virus. Nature. 2008;453:615–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) Influenza vaccines. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2005;80:279–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices–United States, 2013-2014. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62:1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jefferson T, Di Pietrantonj C, Rivetti A, Bawazeer GA, Al-Ansary LA, Ferroni E. Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;7:CD001269. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001269.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodwin K, Viboud C, Simonsen L. Antibody response to influenza vaccination in the elderly: a quantitative review. Vaccine. 2006;24:1159–69. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herzog C, Hartmann K, Künzi V, Kürsteiner O, Mischler R, Lazar H, Glück R. Eleven years of Inflexal V-a virosomal adjuvanted influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2009;27:4381–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sejvar JJ, Kohl KS, Bilynsky R, Blumberg D, Cvetkovich T, Galama J, Gidudu J, Katikaneni L, Khuri-Bulos N, Oleske J, et al. Brighton Collaboration Encephalitis Working Group Encephalitis, myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM): case definitions and guidelines for collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2007;25:5771–92. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collet JP, MacDonald N, Cashman N, Pless R, Advisory Committee on Causality Assessment Monitoring signals for vaccine safety: the assessment of individual adverse event reports by an expert advisory committee. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:178–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alper G. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. J Child Neurol. 2012;27:1408–25. doi: 10.1177/0883073812455104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menge T, Kieseier BC, Nessler S, Hemmer B, Hartung HP, Stüve O. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: an acute hit against the brain. Curr Opin Neurol. 2007;20:247–54. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3280f31b45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennetto L, Scolding N. Inflammatory/post-infectious encephalomyelitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(Suppl 1):i22–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.034256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shoamanesh A, Traboulsee A. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following influenza vaccination. Vaccine. 2011;29:8182–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Machicado JD, Bhagya-Rao B, Davogustto G, McKelvy BJ. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following seasonal influenza vaccination in an elderly patient. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013;20:1485–6. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00307-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakayama T, Onoda K. Vaccine adverse events reported in post-marketing study of the Kitasato Institute from 1994 to 2004. Vaccine. 2007;25:570–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang XF, Li L, Liu DW, Li KL, Wu WD, Zhu BP, Wang HQ, Luo HM, Cao LS, Zheng JS, et al. Safety of influenza A (H1N1) vaccine in postmarketing surveillance in China. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:638–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isai A, Durand J, Le Meur S, Hidalgo-Simon A, Kurz X. Autoimmune disorders after immunisation with Influenza A/H1N1 vaccines with and without adjuvant: EudraVigilance data and literature review. Vaccine. 2012;30:7123–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams SE, Pahud BA, Vellozzi C, Donofrio PD, Dekker CL, Halsey N, Klein NP, Baxter RP, Marchant CD, Larussa PS, et al. Causality assessment of serious neurologic adverse events following 2009 H1N1 vaccination. Vaccine. 2011;29:8302–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pohl D, Tenembaum S. Treatment of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2012;14:264–75. doi: 10.1007/s11940-012-0170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]