ABSTRACT

Purpose

To describe a case of uveal melanoma in the peripheral choroid masquerading as chronic uveitis and to raise awareness about malignant masquerade syndromes.

Case Report

A 36-year-old Chinese woman presented from an outside ophthalmologist with a 6-month history of unilateral chronic uveitis unresponsive to medical therapy in the left eye. She was found to have a uveal melanoma in the retinal periphery and underwent successful enucleation of her left eye. The histopathological diagnosis confirmed the clinical diagnosis.

Conclusions

When uveal melanoma presents in an atypical way, the diagnosis is more difficult. This case highlights the uncommon presentations of malignant melanoma of the choroid. It provides valuable information on how peripheral uveal melanoma can present with clinical signs consistent with an anterior uveitis.

Key Words: uveal melanoma, masquerade syndromes, uveitis, pathology, treatment

Conjunctival injection, blurred vision, presence of cells and flare in the anterior chamber, and iris depigmentation are typical features of uveitis. However, there are also several other ocular conditions that are associated with those features.1,2 Rothova et al.3 point out that masquerade syndromes that include uveal melanoma are diagnosed in 5% of patients with uveitis. Uveitis masquerade syndromes are a group of ocular diseases that present as acute or chronic intraocular inflammation but are not secondary to the typical underlying immune-mediated causes.4 Masquerade syndromes that can be misinterpreted as uveitis include ischemic retinal vascular disease, intraocular foreign bodies, primary vitreal or retinal disorders, and intraocular malignancies.

Here, a case of uveal melanoma of the peripheral choroid that masqueraded as chronic uveitis and resulted in delayed diagnosis is reported. Thorough initial examination is critical to the correct diagnosis, and treatment-resistant ocular inflammation should raise the suspicion of malignant masquerade syndromes.

CASE REPORT

A 36-year-old Chinese woman presented from an outside ophthalmologist with a history of unilateral chronic uveitis unresponsive to medical therapy in the left eye. The patient was first seen for conjunctival redness and blurred vision in the left eye 6 months prior. Clinical records from the initial examination indicated ciliary injection and mild anterior chamber reaction of the left eye. No posterior segment findings were seen and the patient was diagnosed as having unilateral anterior uveitis. She was treated with prednisolone acetate 1% and tropicamide 1% four times a day. Her vision worsened over time. Six months later, the best-corrected visual acuity of the right eye had deteriorated from 20/20 to 20/100.

Upon referral from the initial treating physician, her best-corrected vision was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/100 in the left eye. Intraocular pressures were 13.7 mm Hg in the right eye and 38.7 mm Hg in the left eye. Slit lamp examination of the right eye was unremarkable. Ciliary injection, moderate cells and flare in the anterior segment, iris depigmentation, and powdery keratic precipitates on the posterior surface of the cornea were observed in the left eye (Fig. 1A, B). Heavy pigment deposition was seen on both the anterior and posterior lens capsule and the fundus could not be observed in the left eye. The previous medical history of the patient was normal and no family history of cancer was found.

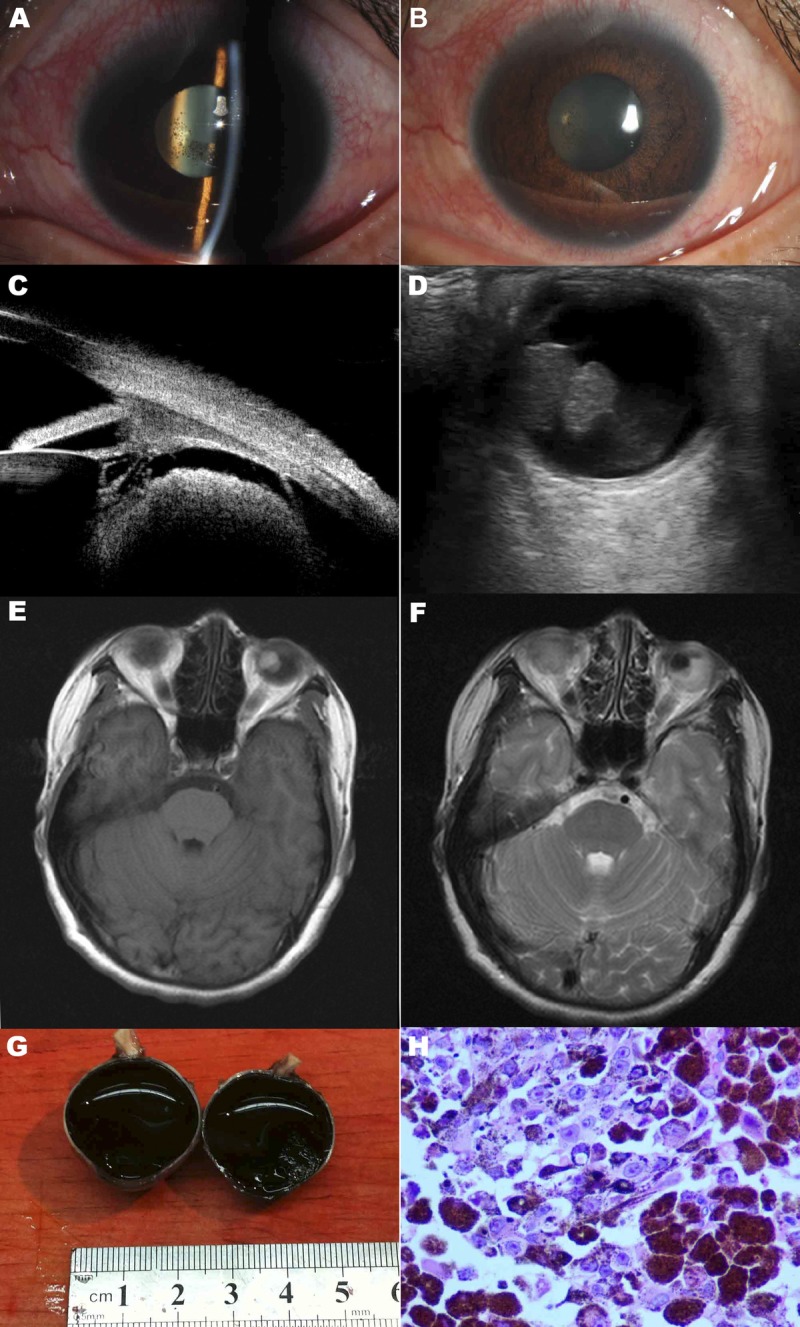

FIGURE 1.

Ophthalmologic findings of the left eye. (A, B) Slit lamp photography of the left eye showing ciliary injection, anterior chamber reaction, and keratic precipitates. (C) A tumor located behind the iris shown on UBM. (D) A large tumor in the peripheral choroid shown on B-scan ultrasonography. (E) T1-weighted contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image of the brain and orbits showing a large mass in the left globe. (F) T2-weighted contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image of the brain and orbits showing a large mass in the left globe. (G) Gross appearance of the tumor. (H) Pathologic section showing large round tumor cells with an epithelioid appearance. The cells contained abundant pink cytoplasm and dusty melanin. Single prominent eosinophilic nucleoli were seen in some melanocytes.

Ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM), B-scan ultrasonography, chest radiography, and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging scan were then performed for further evaluation after appropriate informed consent was obtained from the patient. With the UBM, a tumor located behind the iris was observed (Fig. 1C). B-scan ultrasonography showed a mushroom-shaped mass that was acoustically hollow with reflectivity that was lower than the adjacent choroid. The tumor configuration indicated that the lesion had broken through the Bruch membrane (Fig. 1D). The size of the tumor measured by ultrasonography was 11 mm in height and 9 mm in diameter. To rule out metastases, a full systemic workup was ordered. Ultrasound results of the liver, kidney, and abdomen as well as chest radiography results were all normal. Central nervous system malignancy was ruled out with magnetic resonance imaging. The choroidal melanoma was visualized as a hyper-enhancing mass compared with the adjacent vitreous with T1-weighted imaging and hypo-enhancing with T2-weighted sequences (Fig. 1E, F).

Based on ocular findings, choroidal malignant melanoma with secondary intraocular inflammation and ocular hypertension was diagnosed. The patient underwent enucleation of her left eye. Gross examination of the enucleated globe showed the tumor to be 1.3 cm by 1.0 cm. There was extension to involve a large section of the adjacent choroid, retina, and vitreous (Fig. 1G). Consistent with the clinical diagnosis, the pathologic examination of the mass confirmed it as a melanoma with epithelioid cell type, necrosis, and papillary configuration (Fig. 1H). No invasion of scleral tissues was seen.

At the time of this publication, the patient has remained metastasis free over a half-year follow-up period.

DISCUSSION

Uveal melanoma is the most common tumor of the eye in adults.5 The disease is not only vision threatening but also potentially fatal. The incidence of uveal melanoma is about 1200 to 1500 new cases per year in the United States, and it accounts for about 5% of all melanomas.6 Male sex, being older than 65 years, and rural location of residence are established risk factors.7 There is a wide range of therapeutic options such as radiotherapy, transpupillary thermotherapy, and surgical resection, each with its own risks and benefits.8,9 The recommended treatment depends on many factors, chief among them being the size of the tumor. Size of the tumor at diagnosis is also strongly correlated with survival.10 Choroidal melanoma can be classified by size into small (<3 mm in height and <10 mm in diameter), medium (<15 mm in diameter), and large (>15 mm in diameter or >5 mm in height).11 Based on the results of the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study, medium-sized melanomas may be treated with either iodine plaque brachytherapy or enucleation. Large tumors are usually enucleated with or without pre-enucleation radiation.12 Treatments for small tumors are more variable and evolving with a goal of preserving useful vision. Early diagnosis at a time when the melanoma is small affords a greater likelihood of retention of vision and decreased risk of systemic metastasis. Small melanomas of the peripheral choroid can be clinically missed because of their location behind the iris. Rarely, they can masquerade as an anterior uveitis leading to a delay in diagnosis until their growth makes them visible during fundoscopy.

The type of melanoma cells seen during pathologic examination is also a prognostic factor. First proposed by Callender in 1931 and modified by McLean in 1983, the classification divides melanomas into spindle cell, epithelioid, and mixed cell type based on the morphology of the cells, their nuclei, and nucleoli.13,14 Epithelioid cell type is associated with a far worse prognosis because of higher rates of systemic metastases.15

Nearly one-third of all uveal melanoma cases present asymptomatically. The early detection of small uveal melanoma is a challenge for clinicians. The diagnosis is based on clinical examination with the slit lamp and ophthalmoscope along with ultrasonography. Once diagnosed, systemic investigation to rule out metastatic disease should be undertaken including imaging of the liver, lungs, and central nervous system.

Rarely, cells in the anterior chamber may be the first clinical sign in uveal melanoma. The anterior chamber reaction is a mixture of tumor cells, pigment cells, and inflammatory cells, unlike in immune-mediated anterior uveitis where T-cells predominate. Lentz et al.16 found uveal invasion by mononuclear cells and melanocyte destruction in eyes enucleated with uveal melanoma. High levels of tumor macrophage infiltration, called the inflammatory phenotype, occur more frequently in melanomas of the epithelioid cell type and is associated with lower survival.17 Shields et al.18 pointed out that symptoms of flashes and floaters are high-risk clinical factors predictive of tumor growth. In the presented case, the uveal melanoma in the periphery was small initially and therefore difficult to detect by fundoscopy. The fact that associated symptoms and signs were consistent with chronic uveitis resulted in misdiagnosis. Malignant masquerade uveitis syndromes are typically unilateral and resistant to steroid therapy.19 A uveitis that is nonresponsive to steroids should lead to suspicion of a masquerade syndrome and consideration of imaging technologies including ultrasonography of the peripheral uveal tract. This case highlights an uncommon presentation of malignant melanoma of the peripheral choroid initially manifesting as an anterior uveitis.

It is well known that uveal melanomas often metastasize.20 Although melanoma can metastasize to any location, common sites of metastatic spread are to the liver, lung, bone, and central nervous system. Metastasis is the leading cause of death among uveal melanoma patients. A meta-analysis showed that the 5-year mortality varied by size with a rate of 16% for small, 32% for medium, and 53% for large tumors.11 The results indicated that the tumor size at time of enucleation is a major prognostic factor. Even after successful treatment of uveal melanoma, close follow-up is necessary to monitor for recurrence and metastasis. Recently, gene expression profiling has been suggested to provide a more highly accurate prognosis of metastasis risk.21

Yabo Yang

No. 88, Jiefang Road

Hangzhou, China

e-mail: yabyang@hotmail.com

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kafkala C, Daoud YJ, Paredes I, Foster CS. Masquerade scleritis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2005; 13: 479– 82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tugal-Tutkun I. Pediatric uveitis. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2011; 6: 259– 69 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rothova A, Ooijman F, Kerkhoff F, Van Der Lelij A, Lokhorst HM. Uveitis masquerade syndromes. Ophthalmology 2001; 108: 386– 99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grange LK, Kouchouk A, Dalal MD, Vitale S, Nussenblatt RB, Chan CC, Sen HN.Neoplastic masquerade syndromes in patients with uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2014; 157: 526– 31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bell DJ, Wilson MW. Choroidal melanoma: natural history and management options. Cancer Control 2004; 11: 296– 303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Egan KM, Seddon JM, Glynn RJ, Gragoudas ES, Albert DM. Epidemiologic aspects of uveal melanoma. Surv Ophthalmol 1988; 32: 239– 51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vajdic CM, Kricker A, Giblin M, McKenzie J, Aitken J, Giles GG, Armstrong BK.Incidence of ocular melanoma in Australia from 1990 to 1998. Int J Cancer 2003; 105: 117– 22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shields CL, Cater J, Shields JA, Chao A, Krema H, Materin M, Brady LW.Combined plaque radiotherapy and transpupillary thermotherapy for choroidal melanoma: tumor control and treatment complications in 270 consecutive patients. Arch Ophthalmol 2002; 120: 933– 40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harbour JW, Meredith TA, Thompson PA, Gordon ME. Transpupillary thermotherapy versus plaque radiotherapy for suspected choroidal melanomas. Ophthalmology 2003; 110: 2207– 14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coleman K, Baak JP, Van Diest P, Mullaney J, Farrell M, Fenton M. Prognostic factors following enucleation of 111 uveal melanomas. Br J Ophthalmol 1993; 77: 688– 92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Diener-West M, Hawkins BS, Markowitz JA, Schachat AP. A review of mortality from choroidal melanoma. II. A meta-analysis of 5-year mortality rates following enucleation, 1966 through 1988. Arch Ophthalmol 1992; 110: 245– 50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Singh AD, Kivela T. The collaborative ocular melanoma study. Ophthalmol Clin North Am 2005; 18: 129– 42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Callender GR. Malignant melanotic tumors of the eye: a study of histologic types in 111 cases. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1931; 36: 131– 42 [Google Scholar]

- 14. McLean IW, Foster WD, Zimmerman LE, Gamel JW. Modifications of Callender’s classification of uveal melanoma at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Am J Ophthalmol 1983; 96: 502– 9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gill HS, Char DH. Uveal melanoma prognostication: from lesion size and cell type to molecular class. Can J Ophthalmol 2012; 47: 246– 53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lentz KJ, Burns RP, Loeffler K, Feeney-Burns L, Berkelhammer J, Hook RR., Jr Uveitis caused by cytotoxic immune response to cutaneous malignant melanoma in swine: destruction of uveal melanocytes during tumor regression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1983; 24: 1063– 9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maat W, Ly LV, Jordanova ES, de Wolff-Rouendaal D, Schalij-Delfos NE, Jager MJ. Monosomy of chromosome 3 and an inflammatory phenotype occur together in uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008; 49: 505– 10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shields GL, Shields JA, Kiratli H, De Potter P, Cater JR. Risk factors for growth and metastasis of small choroidal melanocytic lesions. Ophthalmology 1995; 102: 1351– 61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tsai T, O’Brien JM. Masquerade syndromes: malignancies mimicking inflammation in the eye. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2002; 42: 115– 31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kujala E, Makitie T, Kivela T. Very long-term prognosis of patients with malignant uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003; 44: 4651– 9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Field MG, Harbour JW. Recent developments in prognostic and predictive testing in uveal melanoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2014; 25: 234– 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]