Abstract

In 2008, at the request of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Institute of Medicine (IOM) prepared a report identifying knowledge gaps in public health systems preparedness and emergency response and recommending near-term priority research areas. In accordance with the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act mandating new public health systems research for preparedness and emergency response, CDC provided competitive awards establishing nine Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Centers (PERRCs) in accredited U.S. schools of public health. The PERRCs conducted research in four IOM-recommended priority areas: (1) enhancing the usefulness of public health preparedness and response (PHPR) training, (2) creating and maintaining sustainable preparedness and response systems, (3) improving PHPR communications, and (4) identifying evaluation criteria and metrics to improve PHPR for all hazards. The PERRCs worked closely with state and local public health, community partners, and advisory committees to produce practice-relevant research findings. PERRC research has generated more than 130 peer-reviewed publications and nearly 80 practice and policy tools and recommendations with the potential to significantly enhance our nation's PHPR to all hazards and that highlight the need for further improvements in public health systems.

Strengthening the preparedness of the United States to prevent, protect against, respond to, and recover from threatened or actual terrorist attacks, major disasters, and other emergencies is a shared responsibility of public and private organizations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) plays a leading role in preparedness and response activities as well as building and strengthening our national health security. CDC's Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response (OPHPR) works with state, tribal, local, territorial, national, and international public health partners to create the expertise, information, trainings, and tools that public health practitioners, people in communities, and partner organizations need to protect their health from natural and manmade threats. This article provides an overview of the OPHPR's Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Centers (PERRCs) program, the first and only program of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to use a public health systems research approach to investigate and improve the complex public health preparedness and response (PHPR) system.

Public health systems research is a relatively new field that OPHPR defined operationally for this program as the development and use of methodologies to understand, model, and measure the influence of change in a complex entity comprising interrelated constituent parts. The 2002 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report “The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century” conceptualizes a public health system as “a complex network of individuals and organizations that have the potential to play critical roles in creating the conditions for health.”1 The 2008 IOM letter report on public health preparedness (PHP) research priorities emphasized six key public health system actors, or sectors, that critically interact with each other and with the governmental public health infrastructure: the health-care delivery system, homeland security and public safety, employers and business, the media, academia, and communities (Figure 1).2 Accordingly, the PERRC program used the public health systems research approach to examine and identify strategies to improve the organization, function, capacity, and performance of various public health system -components in preparing for and responding to any and all potential threats and hazards.

Figure 1.

Main components of the Public Health Emergency Preparedness Systema

aThe filled areas represent the key actors and the empty circles represent the overlap between the key factors, as well as the many less obvious actors that play a significant role in integrating the public health preparedness system. Reprinted with permission from: Institute of Medicine. Research priorities in emergency preparedness and response for public health systems: a letter report. Washington: National Academies Press; 2008.

GAPS IN PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE KNOWLEDGE

The Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act (PAHPA) of 2006 stated the need to define the existing knowledge base for PHPR systems and establish a research agenda based on federal, state, local, and tribal PHP priorities.3 At CDC's request, IOM conducted a study to identify gaps in knowledge about public health systems preparedness and emergency response and articulated recommendations for near-term priority areas for research.2 IOM recommended four priority areas for research to (1) enhance the usefulness of PHP training, (2) improve communications in preparedness and response, (3) create and maintain sustainable preparedness and response systems, and (4) generate criteria for evaluating public health emergency preparedness, response, and recovery, and metrics to measure their effectiveness and efficiency. The report also emphasized the need for the research to address the unique needs of at-risk populations, workforce development, behavioral health, legal and ethical issues, and the use and integration of new technologies.

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE PERRCS

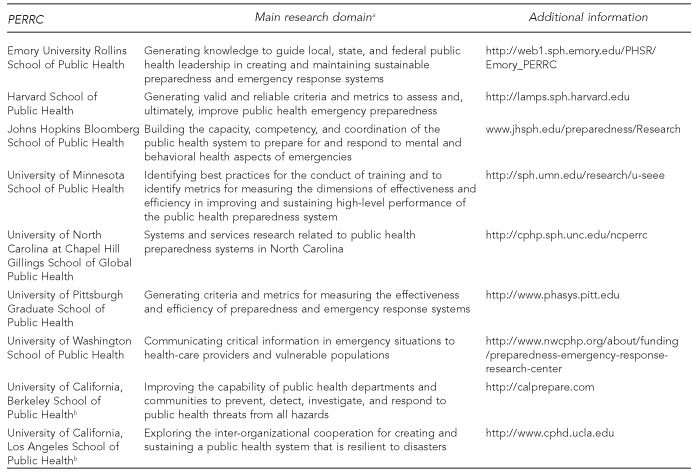

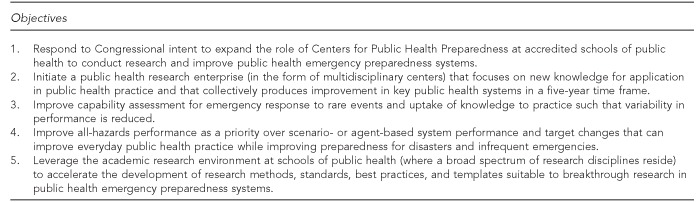

To support the goals of PAHPA, CDC invited applications from accredited U.S. schools of public health to establish the PERRCs.4 Broadly defined in PAHPA-authorizing legislation and guided by the IOM letter report on research priorities, the PERRC program goal and objectives were further specified by CDC OPHPR. The funding announcement initiating the PERRCs stated that the goal of the program was to use a public health systems research approach to strengthen and improve PHP and emergency response capabilities with five specific objectives (Figure 2). Meritorious applications were identified by an external peer-review process to establish nine PERRCs (seven in September 2008 and two a year later) at accredited schools of public health ($57 million was awarded during a period of six years) to conduct research on preparedness and response capabilities and improvements to federal, state, local, and tribal PHPR systems. An integral part of these centers' work is to help translate study results to public health practice, to directly strengthen federal, state, local, and tribal PHPR activities. Figure 3 lists the awarded schools and the IOM research priority addressed by each PERRC. The PERRC research portfolio covered a variety of geographic and at-risk populations.

Figure 2.

OPHPR-defined PERRC program objectives to strengthen and improve public health preparedness and emergency response capabilities using a public health systems research approach

OPHPR = Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response

PERRC = Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Center

Figure 3.

CDC-funded PERRCs and their primary research priorities

aPERRCs addressed some other Institute of Medicine priorities as well. Source: Institute of Medicine. Research priorities in emergency preparedness and response for public health systems: a letter report. Washington: National Academies Press; 2008.

bPERRCs at the University of California, Berkeley, and University of California, Los Angeles, were funded in September 2009, a year after the other seven PERRCS were funded.

CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

PERRC = Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Center

PERRC configuration and management

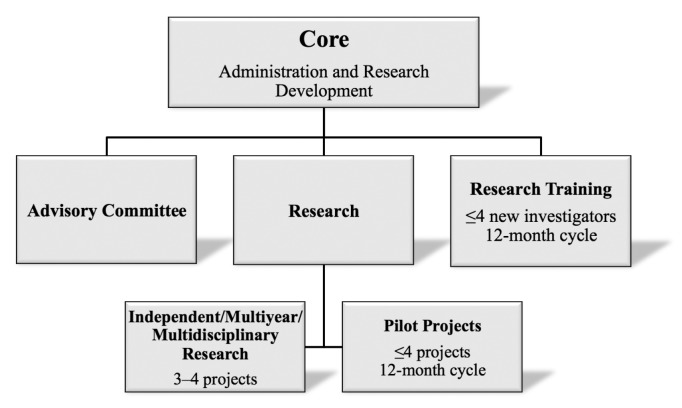

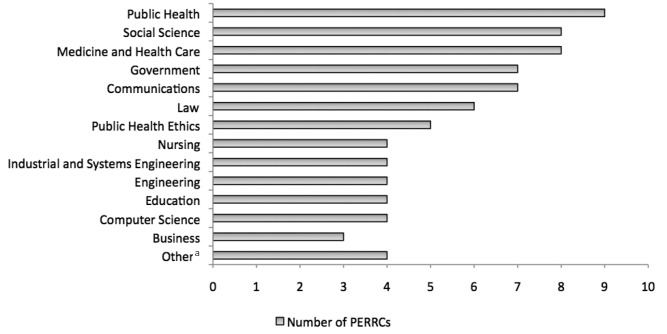

The Extramural Research Program in OPHPR provides programmatic, scientific, and technical assistance to the PERRCs. Each PERRC constitutes an administrative and research development core component and 3–4 investigator-initiated, interrelated, multi-year research projects for a total of 34 major research projects across all PERRCs (Figure 4). In keeping with the Funding Opportunity Announcement requirement for multidisciplinary research projects in each center, the PERRCs' research projects collectively involved investigators from 22 different disciplines, including medicine, health care, social science, government, public health ethics, law, engineering, modeling, and communications (Figure 5). The core component, in addition to providing centralized scientific guidance and financial administration, supported a range of research coordination and translation activities, and managed the PERRC Advisory Committee. The PERRCs funded 30 innovative pilot research projects addressing public health systems preparedness and emergency response capabilities and trained more than 30 new investigators. Each core's fiscal oversight helped ensure research productivity and integration of projects, and enabled the successful leveraging of available resources to address unanticipated research challenges and opportunities, such as fluctuations in research funding and the occurrence of the 2009–2010 H1N1 influenza pandemic.

Figure 4.

PERRC organizational components and activities

PERRC = Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Center

Figure 5.

Disciplines engaged in PERRCs

aOther disciplines that were represented in up to three PERRCs included information and library science, city and regional planning, law enforcement/public safety, emergency medical services, pharmacy, dentistry, veterinary medicine, evaluation science, and psychometrics.

PERRC = Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Center

Throughout the research process, the Advisory Committee for each PERRC provided a critical link to the public health practice community as well as recommendations and guidance on specific research projects. Regularly convened committee meetings provided a venue to validate research objectives and test approaches for communicating research findings in terms that practitioners and the public can understand. The Advisory Committees included members from various sectors and disciplines, including state, local, and/or tribal organizations involved in preparedness and emergency response activities; community liaisons; technical experts; and other stakeholders. These representatives helped ensure that the research was relevant and the results were of practical use for PHPR activities. In many of the research projects, state and local public health practitioners actively collaborated on study activities or served as Advisory Committee members. Some PERRCs also constituted project-specific Advisory Boards to provide more focused subject-matter expertise to the research. For example, the University of California, Berkeley, PERRC Project “Emergency Preparedness Communication” developed a National Advisory Board with subject-matter experts who were knowledgeable of the preparedness needs of people with impairments in hearing or seeing, and a Community Advisory Board in the local San Francisco Bay Area, whose hearing-impaired members provided firsthand knowledge of the functional and access needs of hearing-impaired communities. The Advisory Boards guided investigators in their research to develop practical recommendations relevant to specific at-risk communities.

Key research partners

In addition to state and local public health departments, the PERRCs engaged research partners from various sectors including government, academia, communities, schools, hospitals, public safety, media, and faith-based organizations. These partners served in a number of different roles including providing suggestions about improving research methods, developing research surveys, and working with communities. These important partnerships, totaling about 500 across the PERRCs, helped ensure that research results are relevant to policy and practice in PHPR systems.5

Pilot projects and mentoring of new investigators

The PERRCs supported more than 30 pilot or exploratory projects focused on different IOM research topics and varied in the types of research partners engaged and populations addressed. The PERRCs also engaged in informal new investigator training through the employment of about 200 junior research personnel (primarily students) in PERRC research projects and trained more than 30 new investigators (e.g., post-graduate fellows and faculty members with no prior experience in PHPR research). The PERRC-associated training and mentoring of researchers contributed to the development of a group of future public health systems scientists.

Mid-project evaluation

As a requirement for continued funding, OPHPR organized a comprehensive mid-course evaluation of the PERRCs. OPHPR's Board of Scientific Counselors, which oversees OPHPR's research, scientific, and -programmatic activities, created an ad hoc workgroup to conduct the review in summer 2012. The workgroup assessed the program's relevance, effectiveness, impact, and significance in relation to in-progress research activities and findings addressing the IOM priorities and crosscutting themes, and OPHPR's objectives for the PERRCs (Figure 2). The review also included input from key partner organizations (i.e., Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, National Association of County and City Health Officials, and Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health) to provide the ad hoc workgroup with a practice-oriented view of the PERRC research work. Evaluation results indicated that the PERRC program has helped to build a scientific evidence base for preparedness and response practice. The workgroup noted that PERRCs in general had shown excellent progress, as indicated by the ever-growing list of PERRC publications (available at www.cdc.gov/phpr/science/updates.htm) and evidence-based tools. The workgroup also provided several recommendations, including a call for continued active support of this relatively new research field.5

Realization of the PERRC program objectives

There is evidence that PERRC research objectives (Figure 2) to strengthen and improve PHP and emergency response capabilities have been realized.5 Following are a few examples.

The nine academic centers established by the PERRC program launched a PHP research enterprise. Figure 5 shows the variety of disciplines that have been engaged in the PERRCs to bring diverse perspectives and innovative approaches to the research. Public health, clinical medicine, health-care services, law, engineering, mathematics, and other expertise contributed to a robust systems research approach across all the PERRCs that has resulted in practical insights concerning, for example, PHP communication systems,6–11 cross-sector partnerships and collaboration,12–16 the preparedness policy and legal environment,17–19 workforce challenges,20–25 and performance evaluation and improvement.26–28

Responding to the H1N1 pandemic that emerged within the first year of funding for these new research centers, several of the PERRCs pursued research that contributed to the pandemic response. The H1N1 pandemic-related studies yielded numerous outcomes that can be used to guide future responses to pandemics and other public health emergencies, including enhanced local health department surveillance capabilities,29,30 models to assist local decisions about school closures,31 strategies to address barriers to vaccine uptake among ethnic and minority populations,32 and a Web-based gaming application to educate teens about disease spread and preventive measures.33 These and other timely studies illustrate the program's responsiveness to the second PERRC program objective (Figure 2) of providing new applied knowledge for public health practice, available for uptake to improve public health systems within the five-year project time frame.

The PERRCs addressed the third program objective by conducting critical research to develop evaluation methods, metrics, and modeling approaches that can be used to support capability assessment and reduce system performance variability. Examples of capability assessment strategies developed by the PERRCs included a toolkit to evaluate Medical Reserve Corps performance34 and studies examining how to better use after-action reports35–37 and exercises38–42 for performance improvement. PERRC research pursued modeling of various PHP system phenomena, including mass evacuation,43 the impact of different vaccine distribution strategies,44,45 infectious disease progression in a population,46,47 and effects of variation in mitigation strategies, such as the impact of different school closure approaches.31,45–50 Broad incorporation of modeling findings into policy and practice could reduce system performance variability by helping to standardize guidance for preparedness planning.

Relative to the fourth program objective, findings from PERRC research indicate correlations between improvements in all-hazards preparedness performance and improvements in everyday public health practice. One study found that public health department accreditation and other performance improvement programs have a significant and positive effect on preparedness capacities.51 In another study, research to enhance emergency operations center staff performance yielded more effective teams that enabled a state health department to maintain operations when staffing was severely reduced for a short period.52,53 Yet another study provided evidence that a state could use a regional preparedness and response team to provide effective training and support to local health departments and save costs.29 The many PERRC research outcomes addressing community resilience provide clear examples of outcomes that not only have the potential to improve all-hazards performance and target preparedness enhancements, but can also improve everyday public health practice by boosting local capacity to deliver an array of public health services. For example, findings from an investigation to build faith-based organizations' capacity to perform psychological first aid and disaster planning indicated that the intervention enhanced mental health services provisions for everyday personal and family crises as well as during disasters.54–56 Elsewhere, -findings from an assessment of vaccine-associated adverse event reporting were applied to improve vaccine safety communication during both routine and pandemic vaccination activities.57

The multidisciplinary research conducted by the PERRCs addressed the fifth program objective by yielding innovative approaches to support breakthrough research in PHP systems. Examples of innovative PHPR research include the use of social network analysis to examine the relationships among public health system actors as defined by state-level statutes, regulations, and policies for emergency events;58 an examination of characteristics of effective collaboration in academic-community partnerships for preparedness and response;59,60 and a novel approach to building capacity for public mental health emergency planning and response through collaboration between health departments and faith-based organizations.54,56

These examples and other findings described in this supplemental issue of Public Health Reports demonstrate that the goals and objectives of the PERRC program have been realized by the funding of nine newly formed schools of public health-based research centers during a six-year period. The new knowledge resulting from PERRC research that can be applied to PHPR practice is described in several articles in this supplement and elsewhere.61 The research findings generated by these centers support ongoing efforts to strengthen national health security and the nation's response to and recovery from acts of terrorism, natural disasters, infectious disease outbreaks, and other threats to public health.

PROGRAM OUTCOMES: FROM RESEARCH TO PRACTICE

The 34 individual research projects conducted by the PERRCs during the program's first four years generated more than 130 peer-reviewed publications and nearly 80 practice tools for use in PHP practice to date. The PERRC grant program defines an evidence-based PHP “practice tool” as a practical and usable instrument, intervention, program, policy, strategy, messaging, or practice that facilitates the incorporation of science-based knowledge into PHP practice or policy-making for the improvement of PHP system capabilities or performance. Each tool is supported by specific research evidence indicating its effectiveness. Information regarding these PHP practice tools has been regularly presented at PHP conferences, published in the scientific literature, and shared on PERRC or other websites. These tools have been developed and tested in collaboration with health departments and other PHP system partners, including input from respective PERRC Advisory Committees.

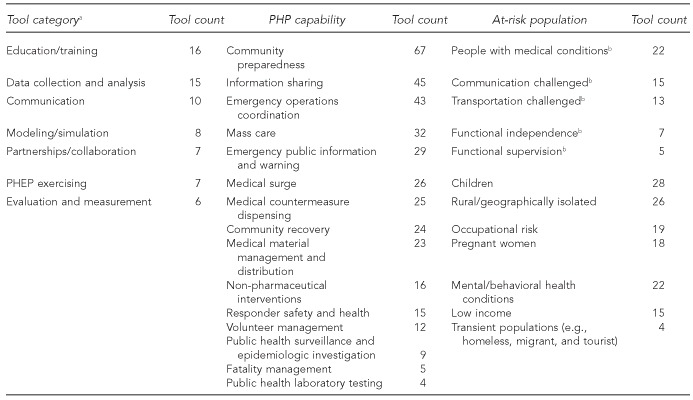

Figure 6 displays the number of PERRC tools that address each of the 15 PHP capabilities62 and each at-risk population (defined by the HHS Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response).63 Figure 6 also presents a list of categories most frequently associated with the PERRC tools. Many of the PERRC tools address two or more capabilities, with each of the 15 capabilities addressed by at least four (e.g., laboratory testing) and up to 67 (e.g., community preparedness) PERRC tools. The tools generated by the five PERRCs could be used to address the needs or improve the preparedness and response of all five categories of at-risk -individuals.63 PERRC practice tools also focus on specific at-risk populations, such as pregnant women and workers with occupational risks. The most frequently noted tool categories suggest that the PERRC tools represent a variety of assistive approaches, including training, data collection/analysis, modeling/simulation, and evaluation and measurement aids. Overall, the nine PERRCs have collectively generated a diverse portfolio of evidence-based interventions for PHP practice that provide at least some coverage of the full range of PHP capabilities and at-risk populations.

Figure 6.

Types of tools developed by the PERRC program, by selected category, targeted PHP capability, and at-risk populations

aExtramural Research Program personnel coded tools by category. Categories focused on type or delivery mode of tools. Tools represent once or more in the different categories within each column.

bDepartment of Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response at-risk functional areas

PERRC = Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Center

PHP = public health preparedness

PHEP = public health emergency preparedness

True achievement of the five PERRC program objectives rests upon the more fundamental aim of creating new knowledge for application in public health practice that will produce PHP system improvements in the near term. CDC explicitly shaped and focused the PERRCs' research activities in the program's fifth and sixth years to foster translation of the research findings to PHP practice.

In the program's fifth year, PERRCs were directed to focus on translation strategies in their research. The nine PERRCs elected to pursue translation-focused activities on 22 of their original 34 individual research projects. Most PERRCs collaborated with practice partners to pilot a research outcome in one or more additional PHP practice settings, and evaluated the effectiveness of the research outcome's application. Five PERRC projects investigated extending the reach of their research outcomes by developing and implementing approaches that generalize or transfer research findings to a broader community. Investigators on two additional projects chose to further elaborate on an innovative outcome or aspect of their completed research findings to add impact or value to preparedness and response practice expected beyond outcomes of the original research effort.

In the sixth and final year of the PERRC program, grantees were asked to extend the PERRC research outcomes to other jurisdictions or populations through the use of technological or other innovative strategies to enable widespread dissemination and uptake of PERRC research products by state and local health departments. The PERRCs are primarily developing Web-based applications, training, portals, and/or dissemination strategies to make research findings broadly accessible; two PERRCs are also examining mobile device applications to deliver public health communication interventions and tools.

Grants supporting 34 multidisciplinary PHP research projects, research translation, and other PERRC activities yielded dozens of evidence-based tools and outcomes, many of which were refined, elaborated, and further tested in collaboration with additional public health practice organizations. In the future, many of these preparedness and response tools will be available via Internet- and mobile-based technologies for public health program access and adoption. Additional systematic effort will be needed to promote further translation and adoption of the PERRC program's research findings into practice.

CONCLUSIONS

Significant investments by government agencies, including CDC, in core PHPR capabilities have improved our nation's ability to successfully prevent, mitigate, respond to, and recover from incidents with potentially negative health consequences. The PERRC program represents the first major federal investment in public health systems research to address preparedness and response knowledge and performance gaps. The PERRCs established a strong foundation for all-hazards PHPR-related research and embody a network of preparedness-focused researchers and practitioners. The PERRC programs fostered a research infrastructure that supported the training of a new generation of public health systems investigators and developed evidence-based knowledge that can improve preparedness and response program performance. As noted in the mid-project evaluation report, the PERRCs have contributed to the scientific body of evidence for preparedness and response practice.5 By design, the PERRCs established multidisciplinary Advisory Committees and worked closely with state and local public health partners, community organizations, and other public health system partners to identify and conduct public health practice-relevant research intended to improve system performance. Following this investment of time, intellect, and energy, it is now necessary to ensure the translation and application of the PERRC program's research findings to improve our nation's health security.

Footnotes

The authors thank Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) colleagues Geraldina Villalobos-Quezada and Tara Strine for their contributions to analysis of data from the Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Centers program, and Sam Groseclose for providing comments on the draft.

The contents, findings, and views contained in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official programs and policies of CDC, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Washington: National Academies Press; 2002. The future of the public's health in the 21st century. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Washington: National Academies Press; 2008. Research priorities in emergency preparedness and response for public health systems: a letter report. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pub. L. No. 109–417, §101 et seq. (2006)

- 4.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Coordinating Office for Terrorism Preparedness and Emergency Response (US) Funding opportunity announcement RFA-TP-08-001: preparedness and emergency response research centers: a public health systems approach (P01) 2008. [cited 2014 Jul 23]. Available from: URL: http://www.federalgrants.com/Preparedness-and-Emergency-Response-Research-Research-Centers-A-Public-Health-Systems-Approach-P01-12028.html.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response. Preparedness and emergency response research centers (PERRC) mid-project review: a report from the Board of Scientific Counselors (BSC). 2012 [cited 2014 Jul 23] Available from: URL: www.cdc.gov/phpr/science/documents/ERPO_Review_PERRC_Program_Review_Workgroup_Report_Final2.pdf.

- 6.Karasz H, Bogan S. What 2 know b4 u text: short message service opportunities for local health departments. Wash State J Public Health Pract. 2011;4:20–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirchhoff K, Turner AM, Axelrod A, Saavedra F. Application of statistical machine translation to public health information: a feasibility study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:473–8. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagassé LP, Rimal RN, Smith KC, Storey JD, Rhoades E, Barnett DJ, et al. How accessible was information about H1N1 flu? Literacy assessments of CDC guidance documents for different audiences. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeder B, Turner AM. Scenario-based design: a method for connecting information system design with public health operations and emergency management. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44:978–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yip MP, Ong BN, Meischke HW, Feng SX, Calhoun R, Painter I, et al. The role of self-efficacy in communication and emergency response in Chinese limited English proficiency (LEP) populations. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14:400–7. doi: 10.1177/1524839911399427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magee M, Isakov A, Paradise HT, Sullivan P. Mobile phones and short message service texts to collect situational awareness data during simulated public health critical events. Am J Disaster Med. 2011;6:379–85. doi: 10.5055/ajdm.2011.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stajura M, Glik D, Eisenman D, Prelip M, Martel A, Sammartinova J. Perspectives of community- and faith-based organizations about partnering with local health departments for disasters. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:2293–311. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9072293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gamboa-Maldonado T, Marshak HH, Sinclair R, Montgomery S, Dyjack DT. Building capacity for community disaster preparedness: a call for collaboration between public environmental health and emergency preparedness and response programs. J Environ Health. 2012;75:24–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engelman A, Ivey SL, Tseng W, Dahrouge D, Brune J, Neuhauser L. Responding to the deaf in disasters: establishing the need for systematic training for state-level emergency management agencies and community organizations. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:84. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seib K, Gleason C, Richards JL, Chamberlain A, Andrews T, Watson L, et al. Partners in immunization: 2010 survey examining differences among H1N1 vaccine providers in Washington State. Public Health Rep. 2013;128:198–211. doi: 10.1177/003335491312800310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markiewicz M, Bevc CA, Hegle J, Horney JA, Davies M, MacDonald PD. Linking public health agencies and hospitals for improved emergency preparedness: North Carolina's public health epidemiologist program. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:141. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karasz HN, Eiden A, Bogan S. Text messaging to communicate with public health audiences: how the HIPAA Security Rule affects practice. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:617–22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodge JG, Jr, Rutkow L, Corcoran AJ. Mental and behavioral health legal preparedness in major emergencies. Public Health Rep. 2010;125:759–62. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vernick JS, Gakh M, Rutkow L. Emergency detention of persons with certain mental disorders during public health disasters: legal and policy issues. Am J Disaster Med. 2012;7:295–302. doi: 10.5055/ajdm.2012.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnett DJ, Thompson CB, Errett NA, Semon NL, Anderson MK, Ferrell JL, et al. Determinants of emergency response willingness in the local public health workforce by jurisdictional and scenario patterns: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:164. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lempel H, Epstein JM, Hammond RA. Economic cost and health care workforce effects of school closures in the U.S. PLoS Curr. 2009;1:RRN1051. doi: 10.1371/currents.RRN1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Keefe KA, Shafir SC, Shoaf KI. Local health department epidemiologic capacity: a stratified cross-sectional assessment describing the quantity, education, training, and perceived competencies of epidemiologic staff. Front Public Health. 2013;1:64. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2013.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watson CM, Barnett DJ, Thompson CB, Hsu EB, Catlett CL, Gwon HS, et al. Characterizing public health emergency perceptions and influential modifiers of willingness to respond among pediatric healthcare staff. Am J Disaster Med. 2011;6:299–308. doi: 10.5055/ajdm.2011.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balicer RD, Barnett DJ, Thompson CB, Hsu EB, Catlett CL, Watson CM, et al. Characterizing hospital workers' willingness to report to duty in an influenza pandemic through threat- and efficacy-based assessment. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:436. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar S, Quinn SC, Kim KH, Daniel LH, Freimuth VS. The impact of workplace policies and other social factors on self-reported influenza-like illness incidence during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:134–40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Araz OM, Jehn M. Improving public health emergency preparedness through enhanced decision-making environments: a simulation and survey based evaluation. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2013;80:1775–81. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samoff E, MacDonald PD, Fangman MT, Waller AE. Local surveillance practice evaluation in North Carolina and value of new national accreditation measures. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;19:146–52. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318252ee21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, May L, Stoto MA. Evaluating syndromic surveillance systems at institutions of higher education (IHEs): a retrospective analysis of the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic at two universities. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:591. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horney JA, Markiewicz M, Meyer AM, MacDonald PD. Support and services provided by public health regional surveillance teams to local health departments in North Carolina. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2011;17:E7–13. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181d6f7fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samoff E, Waller A, Fleischauer A, Ising A, Davis MK, Park M, et al. Integration of syndromic surveillance data into public health practice at state and local levels. Public Health Rep. 2012;127:310–7. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potter MA, Brown ST, Cooley PC, Sweeney PM, Hershey TB, Gleason SM, et al. School closure as an influenza mitigation strategy: how variations in legal authority and plan criteria can alter the impact. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:977. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quinn SC, Kumar S, Freimuth VS, Musa D, Casteneda-Angarita N, Kidwell K. Racial disparities in exposure, susceptibility, and access to health care in the US H1N1 influenza pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:285–93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.188029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larson RC, Hashmi S, Perches M. Flu math games [cited 2014 Jul 24] Available from: URL: http://blossoms.mit.edu/video/larson2.html.

- 34.Savoia E, Massin-Short S, Higdon MA, Tallon L, Matechi E, Stoto MA. A toolkit to assess Medical Reserve Corps units' performance. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2010;4:213–9. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2010.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savoia E, Agboola F, Biddinger PD. Use of after action reports (AARs) to promote organizational and systems learning in emergency preparedness. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:2949–63. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9082949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stoto MA, Nelson C, Higdon MA, Kraemer J, Hites L, Singleton CM. Lessons about the state and local public health system response to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic: a workshop summary. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;19:428–35. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182751d3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stoto MA, Nelson C, Higdon MA, Kraemer J, Singleton CM. Learning about after action reporting from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic: a workshop summary. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;19:420–7. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182751d57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agboola F, McCarthy T, Biddinger PD. Impact of emergency preparedness exercise on performance. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;19(Suppl 2):S77–83. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e31828ecd84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Savoia E, Preston J, Biddinger PD. A consensus process on the use of exercises and after action reports to assess and improve public health emergency preparedness and response. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2013;28:305–8. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X13000289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunter JC, Yang JE, Petrie M, Aragon TJ. Integrating a framework for conducting public health systems research into statewide operations-based exercises to improve emergency preparedness. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:680. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hegle J, Markiewicz M, Benson P, Horney J, Rosselli R, MacDonald P. Lessons learned from North Carolina public health regional surveillance teams' regional exercises. Biosecur Bioterror. 2011;9:41–7. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2010.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biddinger PD, Savoia E, Massin-Short SB, Preston J, Stoto MA. Public health emergency preparedness exercises: lessons learned. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 5):100–6. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Epstein JM, Pankajakshan R, Hammond RA. Combining computational fluid dynamics and agent-based modeling: a new approach to evacuation planning. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larson RC, Teytelman A. Modeling the effects of H1N1 influenza vaccine distribution in the United States. Value Health. 2012;15:158–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yarmand H, Ivy JS, Denton B, Lloyd AL. Optimal two-phase vaccine allocation to geographically different regions under uncertainty. Eur J Oper Res. 2014;233:208–19. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teytelman A, Larson RC. Modeling influenza progression within a continuous-attribute heterogeneous population. Eur J Oper Res. 2012;220:238–50. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yarmand H, Ivy JS. Analytic solution of the susceptible-infective epidemic model with state-dependent contact rates and different intervention policies. Simulation. 2013;89:703–21. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown ST, Tai JHY, Bailey RR, Cooley PC, Wheaton WD, Potter MA, et al. Would school closure for the 2009 H1N1 influenza epidemic have been worth the cost?: a computational simulation of Pennsylvania. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:353. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yarmand H, Ivy JS, Roberts SD. Identifying optimal mitigation strategies for responding to a mild influenza epidemic. Simulation. 2013;89:1400–15. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee BY, Brown ST, Cooley P, Grefenstette JJ, Zimmerman RK, Zimmer SM, et al. Vaccination deep into a pandemic wave: potential mechanisms for a “third wave” and the impact of vaccination. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:e21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davis MV, Bevc CA, Schenck AP. Effects of performance improvement programs on preparedness capacities. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(Suppl 4):19–27. doi: 10.1177/00333549141296S404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riley W, Bowen PA, Scullard M, Petersen-Kroeber C. Methodologies to study and improve team performance, decision-making, and training in a DOC. Presentation at the 2012 AcademyHealth Public Health Systems Research (PHSR) Interest Group Meeting; 2012 Jun 26–27; Orlando, Florida. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riley W, Bowen PA, Scullard M, Petersen-Kroeber C. Methodologies to study and improve team performance, decision-making, and training in a DOC. Presentation at the 2012 AcademyHealth Public Health Systems Research (PHSR) Interest Group Meeting; 2012 Jun 26–27; Orlando, Florida. Also available from: URL: http://www.academyhealth.org/files/phsr/3-Bowen.pdf [cited 2014 Jul 24] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCabe OL, Perry C, Azur M, Taylor HG, Bailey M, Links JM. Psychological first-aid training for paraprofessionals: a systems-based model for enhancing capacity of rural emergency responses. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2011;26:251–8. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X11006297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCabe OL, Marum F, Semon N, Mosley A, Gwon H, Perry C, et al. Participatory public health systems research: value of community involvement in a study series in mental health emergency preparedness. Am J Disaster Med. 2012;7:303–12. doi: 10.5055/ajdm.2012.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCabe OL, Perry C, Azur M, Taylor HG, Gwon H, Mosley A, et al. Guided preparedness planning with lay communities: enhancing capacity of rural emergency response through a systems-based partnership. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2013;28:8–15. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X12001483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meranus D, Stergachis A, Arnold J, Duchin J. Assessing vaccine safety communication with healthcare providers in a large urban county. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:269–75. doi: 10.1002/pds.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sweeney PM, Bjerke EF, Guclu H, Keane CR, Galvan J, Gleason SM, et al. Social network analysis: a novel approach to legal research on emergency public health systems. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;19:E38–40. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e31829fc013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dunlop AL, Logue KM, Beltran G, Isakov AP. Role of academic institutions in community disaster response since September 11, 2001. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2011;5:218–26. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2011.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dunlop AL, Logue KM, Vaidyanathan L, Isakov AP. Facilitators and barriers for effective academic-community collaboration for disaster preparedness and response. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2012 doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182205087. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response. ERP Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Centers (PERRCs)—program updates [cited 2014 Jul 24] Available from: URL: www.cdc.gov/phpr/science/updates.htm.

- 62.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Public health preparedness capabilities: national standards for state and local planning. March 2011 [cited 2014 Jul 24] Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/capabilities/DSLR_capabilities_July.pdf.

- 63.Department of Health and Human Services (US) At-risk individuals [cited 2014 Jul 23] Available from: URL: www.phe.gov/preparedness/planning/abc/pages/at-risk.aspx.