Abstract

Objective

In response to public health systems and services research priorities, we examined the extent to which participation in accreditation and performance improvement programs can be expected to enhance preparedness capacities.

Methods

Using data collected by the Local Health Department Preparedness Capacities Assessment Survey, we applied a series of weighted least-squares models to examine the effect of program participation on each of the eight preparedness domain scores. Participation was differentiated across four groups: North Carolina (NC) accredited local health departments (LHDs), NC non-accredited LHDs, national comparison LHDs that participated in performance or preparedness programs, and national comparison LHDs that did not participate in any program.

Results

Domain scores varied among the four groups. Statistically significant positive participation effects were observed on six of eight preparedness domains for NC accreditation programs, on seven domains for national comparison group LHDs that participated in performance programs, and on four domains for NC non-accredited LHDs.

Conclusions

Overall, accreditation and other performance improvement programs have a significant and positive effect on preparedness capacities. While we found no differences among accredited and non-accredited NC LHDs, this lack of significant difference in preparedness scores among NC LHDs is attributed to NC's robust statewide preparedness program, as well as a likely exposure effect among non-accredited NC LHDs to the accreditation program.

Understanding the influence of accreditation and performance improvement programs is among the priorities of the public health systems and services research agenda.1 This study advances this research priority by examining the relationship between performance improvement programs and preparedness capacities.

The now 25-year-old Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, “The Future of Public Health,”2 proposed that national, state, and local government agencies work together to improve the public health infrastructure. Foundational initiatives to address that proposal include Turning Point,3 Mobilizing Action through Planning and Partnerships,4 the National Public Health Performance Standards Program (NPHPSP),5 the Exploring Accreditation Project,6 and the Multi-State Learning Collaborative.7 These initiatives resulted in frameworks for performance management, approaches to improving infrastructure through assessment against the 10 Essential Services,8 state-based and national voluntary public health department accreditation programs, and adoption and application of quality improvement practices in health departments.5–9

Within this context, public health preparedness (PHP) became central to the public health mission in response to the 2001 anthrax attacks and subsequent events.10 Since 2002, Congress has appropriated more than $9 billion to state and local public health agencies to develop and implement all-hazards PHP.11 Local health departments (LHDs) are essential to emergency preparedness and response activities. They have the statutory authority to perform key functions including community health assessments and epidemiologic investigations, enforcement of health laws and regulations, and coordination of the local public health system.12

Despite the considerable investment in PHP, there are still gaps and variations in the performance of preparedness activities.13,14 Heterogeneity in the composition and structure of public health systems is an important source of variation in preparedness, as it is in other aspects of public health practice. Further, performance standards for preparedness have been developed by various agencies and organizations, resulting in overlapping and sometimes inconsistent recommendations and program requirements.15 As recently as 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released the Public Health Preparedness Capabilities, which consisted of 15 capabilities designed to serve as national PHP standards to assist state health departments and LHDs with strategic planning.16

An IOM report noted that systems of preparedness should be accountable for achieving performance expectations and proposed that an accreditation program could be a performance monitoring and accountability system for agency preparedness.17,18 Moreover, accreditation can encourage LHD participation in other beneficial performance improvement strategies.19,20

The Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB) is charged with developing and managing national voluntary public health accreditation for tribal, state, local, and territorial health departments. The goal of national accreditation is to improve and protect the health of every community by advancing the quality and performance of public health departments. The PHAB standards 1.0, released in 2011, included a specific Emergency Preparedness Standard as well as additional standards that are linked to preparedness measures.21 There has been considerable interest, including a PHAB Think Tank, in the extent to which PHAB standards and measures are well aligned with22 public health emergency preparedness capabilities.18 In 2009, PHAB conducted a beta test to pilot processes as well as draft standards and measures, which included 19 LHDs.23 As part of their participation, health departments were required to conduct a quality improvement project to address gaps identified in the self-assessment against the PHAB standards.24

Among several state programs that informed PHAB development is the legislatively mandated North Carolina Local Health Department Accreditation (NCLHDA) program. NCLHDA program objectives are to increase the capacity, accountability, and consistency of the policies and practices of all North Carolina (NC) LHDs.25 On an annual basis, 10 LHDs participate in the program for the first time, with all LHDs required to participate by 2014. Reaccreditation is required every four years.25,26 The NCLHDA includes activities that directly measure 12 preparedness capacities, such as surveillance and investigation. An additional 60 activities indirectly or potentially measure preparedness capacities. As of December 2013, 82 of the 85 NC LHDs had achieved accreditation status.

The NPHPSP, also a precursor to national accreditation, provides a framework to assess the capacity and performance of public health systems and public health governing bodies and identify areas for system improvement. LHDs and their partners use tailored instruments to assess the performance of their public health systems against model standards, including preparedness standards, which are based on the 10 Essential Services, NPHPSP version 2.0.5,8 The second version of the assessment instruments and the related program materials strengthened the program's -quality improvement aspect.5 More than 400 public health systems and governing entities used the version 2 assessment instruments.27

In addition, several initiatives are designed to specifically improve PHP functioning. Among these initiatives is Project Public Health Ready (PPHR), a competency-based training and recognition program that assesses local preparedness and helps LHDs, or LHDs working collaboratively as a region, respond to emergencies.28 To achieve PPHR recognition, LHDs must meet nationally recognized standards in all-hazards preparedness planning, workforce capacity development, and demonstration of readiness through exercises or real events. Since 2004, 300 LHDs in 27 states have been recognized as meeting all PPHR requirements individually or working collaboratively as a region.

To understand the impact of these performance improvement and accountability strategies, we examined the effect of participation in these initiatives on LHD preparedness capacities.

METHODS

We used a natural experiment design for this study to examine differences in preparedness domain scores between a state with LHDs exposed to an accreditation program (NC) and a national comparison group of LHDs in states without accreditation programs. NC LHDs, which have all been exposed to the NCLHDA program and must go through it by 2014, were divided into two groups: accredited participants and non-accredited participants. National comparison group LHDs were divided into program participants and non-participants. Previous research indicates that LHDs that participate in at least performance improvement efforts can enhance performance throughout the LHD.29 We accounted for this potential effect by identifying performance improvement efforts that could affect preparedness capacities in the comparison group where program records were available at the LHD level. These efforts included the PHAB beta-test, the NPHPSP, and PPHR. Our analyses examined four groups: (1) NCLHDA accredited participants, (2) NCLHDA non-accredited participants, (3) national comparison group program participants, and (4) national comparison group non-program participants.

Sample

The sample included 85 NC LHDs and 248 LHDs distributed across 39 states, selected using a propensity score matching methodology.14 Propensity score matching selection criteria were based on a set of representative public health agency and system characteristics obtained from the National Association of County and City Health Officials 2010 Profile (n=2,151)13 and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Area Health Resource File (ARF)28 (n=3,225), including scope of services delivered, annual agency expenditures per capita, population size served, socioeconomic characteristics of the community (e.g., percent living in poverty, percent nonwhite, and rural/urban composition), and other health resources within the community.14,30–32 NC LHDs that had achieved accreditation through the NCLHDA program from 2005 through 2010 were designated as NC Accredited; all other NC LHDs were designated as NC Not Accredited. PPHR participation was designated through PPHR recognition from 2004 to 2010. PHAB participation was determined from the list of 19 LHDs that participated as beta test sites.23 NPHPSP participation was determined through a review of the cumulative report of all local public health systems that completed the NPHPSP Version 2 survey from October 21, 2007, to June 10, 2010. Participation was denoted by engagement with one or more programs prior to completion of the Local Health Department Preparedness Capacity Survey (PCAS).14 National comparison LHDs that had not participated in a preparedness program were used as the referent category. We examined the performance of these four groups on the eight preparedness domains.

Variables

Information on the preparedness characteristics of this sample was collected using the 2010 PCAS. The PCAS instrument contains a set of 58 questions with 211 sub-questions that ask LHDs to report if they have a specific preparedness or response capacity (yes/no), with related sub-questions to determine if they have specific elements associated with the particular capacity. The instrument was developed through a Delphi and pilot test process and has undergone extensive validity and reliability testing. Kappa statistics and z-scores indicated substantial-to-moderate agreement among respondents within an LHD. Cronbach's alpha coefficients ranged from 0.6 to 0.9 across the domains.14

Rather than report a single index measure, these capacities measure the following preparedness domains:

Surveillance and Investigation (20 measures): management of urgent case reports, access to a specimen transportation system, electronic storage of local case report data, and access to a public health surveillance system;

Plans and Protocols (25 measures): surge capacity, formal case investigations, and updates and implementations to an all-hazards emergency preparedness and response plan;

Workforce and Volunteers (17 measures): volunteer registry, emergency preparedness staff, preparedness coordinator, public information officer, and the assessment and training of an emergency preparedness workforce;

Communication and Information Dissemination (33 measures): local emergency communications plan, capacity and assessment of communication technologies, and the ability and use of a health alert network;

Incident Command (five measures): access and use of emergency operations center and local incident command structure;

Legal Preparedness (eight measures): extent of legal power and authority in emergency preparedness and response, and access and use of legal counsel;

Emergency Events and Exercises (four measures): LHD engagement in emergency events and exercises in the previous year; and

Corrective Action Activities (28 measures): debriefing, evaluation, and reporting activities following exercises and real events.

LHD capacity was assessed across the eight domains with a range of individual capacity measures (4–33 per domain). Due to the embedded nature of the questions, responses to sub-questions were coded as not applicable if the parent question response was “no.” Within each domain, capacities reported were nested relative to the question and sub-question structure, where the proportion of capacities within each domain's sub-questions were averaged across each domain, thus creating an equally weighted proportion (range: 0–1) of aggregate reported capacities (accounting for the parent/child relationships).

To control for background covariates (i.e., LHD characteristics), the propensity scores added to the model allowed us to more accurately determine whether or not participation in an accreditation or other performance improvement program had a significant effect on local preparedness, by reducing the potential noise associated with program participation.29 Using quantiles of the estimated propensity score, LHDs were stratified into four dummy variables for each group. LHDs assigned to the upper fourth quantile (n=82) represented those health departments whose characteristics were most similar to those in NC.

Analysis

We calculated means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each domain for each of the four groups. To provide an initial comparison, we conducted an analysis of variance to determine if there were any significant differences in domain scores across the participation groups. Program participation and the upper propensity score quantile group were coded as a fixed binary variable to help determine if program participation has a significant effect on levels of preparedness capacity. Using weighted least-squares analyses, we then regressed the composite measure of the eight preparedness domains onto program participation and the control characteristics. In our model, after weighting relative to program participation, the control characteristics variable was used to help balance the covariates among the LHDs and, thus, reduce this confounding and selection bias for the effects of NC. The resulting estimates generated from the model, for the propensity-score matched quantile variable, provided additional protection against this potential bias.

RESULTS

In total, 264 LHDs responded to the PCAS (response rate = 79.3%). A majority (61.6%) were governed by a local board of health. The sample was evenly distributed between LHDs within metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) (51.7%) and those in non-metro areas (48.3%). Responding LHDs reported an average of 96 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees (median = 54; range: 2–1,025). Population size served ranged from 4,000 to 1,484,645 residents, with a median population of 54,261 (mean = 109,803). The percentage of residents living at or below the federal poverty level ranged from 2.9% to 26.5%, with an average of 12.7%. On average, responding LHDs spent $68.86 per capita (adjusted expenditures) on FTE employees per year (range: $0.68–$358.97, median = $53.12). We found no significant differences in the characteristics between responding LHDs and the total sample based on Welch's two-sample t-test (data not shown).

Among the 83 (98%) NC LHDs, 48 (58%) were accredited participants and 35 (42%) were non-accredited participants. Among the 181 (76%) national comparison group LHDs, 138 (76%) had not participated in any performance program and 43 (24%) had participated in at least one performance program. Among the 43 LHDs that had participated, most (n=33) had participated in PPHR, 16 had participated in NPHPSP, and six were PHAB beta test sites. Of these LHDs, one participated in both PPHR and the PHAB beta test, four participated in both PPHR and NPHPSP, and one participated in all three programs (data not shown).

Levels and measures of preparedness

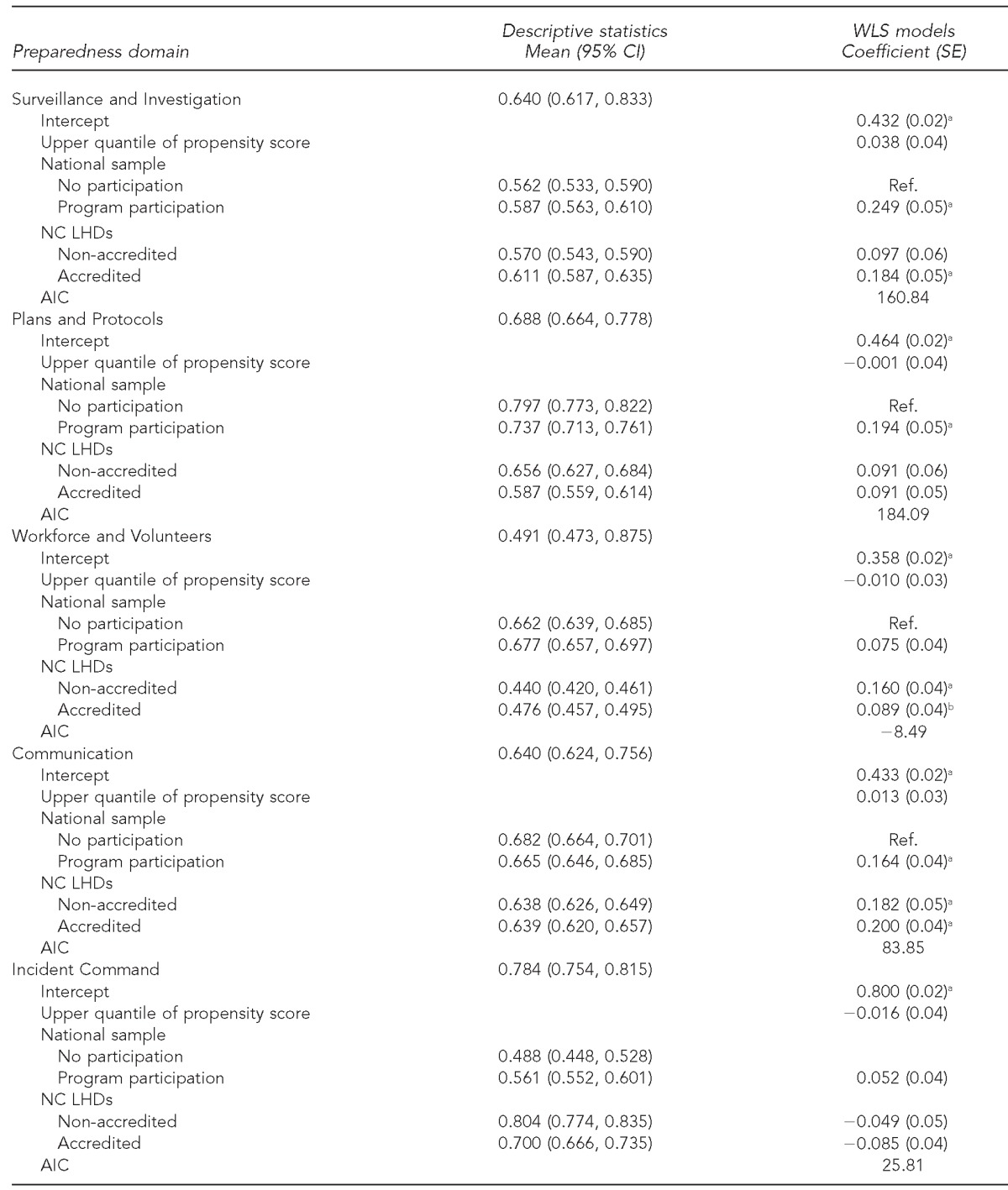

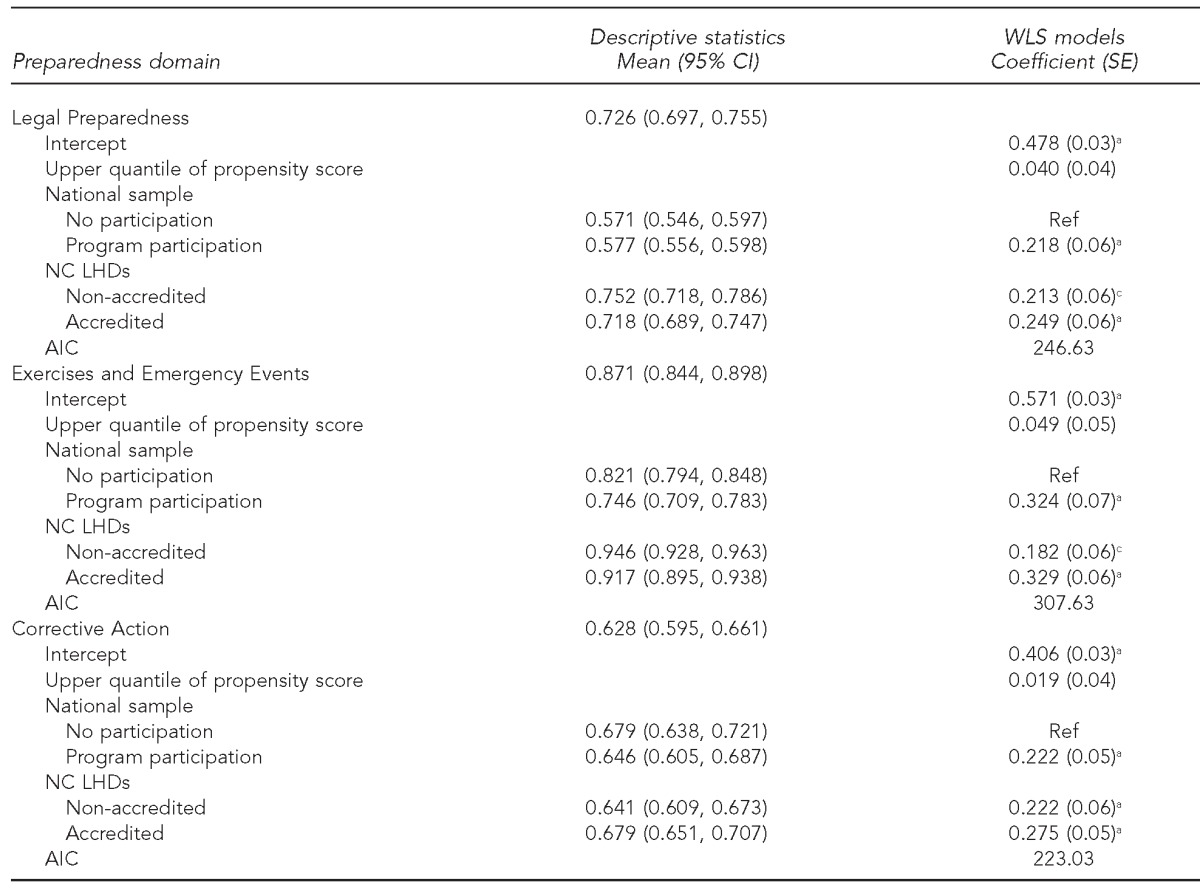

Among the eight domains, preparedness levels varied across the four LHD groups (Table). Average preparedness levels were overall higher among LHDs for the Exercises and Emergency Events domain (0.871, 95% CI 0.844, 0.898), while the Workforce and Volunteers domain had a much lower mean score (0.491, 95% CI 0.473, 0.875) among all LHDs. For the remaining domains, mean levels varied from 0.628 (95% CI 0.595, 0.661) for Corrective Action Activities, 0.640 (95% CI 0.617, 0.883) for Surveillance and Investigation, 0.640 (95% CI 0.624, 0.756) for Communication, and 0.688 (95% CI 0.664, 0.778) for Plans and Protocols, to 0.784 for Incident Command (95% CI 0.754, 0.815) and 0.726 (95% CI 0.697, 0.755) for Legal Preparedness.

Table.

WLS models for preparedness domain scores among North Carolina accredited and non-accredited LHDs, national comparison LHDs participating in performance improvement programs, and national comparison LHDs that did not participate in any program, 2010

aStatistically significant at p<0.001

bStatistically significant at p<0.05

cStatistically significant at p<0.01

WLS = weighted least squares

LHD = local health department

CI = confidence interval

SE = standard error

Ref. = reference group

NC = North Carolina

AIC = Akaike Information Criterion

Within the groups, the lowest observed mean score was among NC non-accredited participants for Workforce and Volunteers (0.440, 95% CI 0.420, 0.461) and the highest score among all groups was in Exercises and Emergency Events, with the highest score of 0.946 (95% CI 0.928, 0.963) for NC non-accredited participants (Table). Levels of preparedness varied among the four groups, with significant differences between groups. Initial analysis of variance identified significant variation among the groups for three domains, including Surveillance and Investigation (F=7.438), Plans and Protocols (F=8.341), and Corrective Action Activities (F=2.877) (data not shown).

Association between performance programs and preparedness

Overall, participation in the NC accreditation program was significantly associated with higher performance on six of the eight domains scores of LHDs when compared with national comparison LHDs that did not participate in any program. These domains were Surveillance and Investigation, Workforce and Volunteers, Communication, Legal Preparedness, Exercises and Emergency Events, and Corrective Action. Among national comparison LHDs, participation in a performance improvement program was associated with higher performance for all domain scores except Incident Command. There was also a significant effect of participation among non-accredited participant NC LHDs in four out of eight domains. In the domains of Communication, Legal Preparedness, Exercises and Emergency Events, and Corrective Action Activities, we found that accredited and non-accredited NC LHDs and LHDs that had participated in a performance improvement effort all had significantly higher domain scores than national comparison LHDs that had not participated in any performance improvement programs. In post-hoc tests, the models were repeated after removing the propensity score control for the matched comparison group. The results yielded the same outcomes, with only minimal Akaike Information Criterion for model selection improvement in two of the eight domain models (Workforce and Volunteers and Incident Command) (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This study is among the first to examine the influence of participation in accreditation and performance improvement programs on program outcomes, specifically preparedness measures. Across domain scores among the entire sample, there was considerable variation in preparedness capacities. Given that the domains cover a wide range of preparedness capacities, different domains of PHP may be more (or less) responsive to contextual effects. We found that participation in the NC accreditation program and other performance improvement programs among a matched sample of LHDs had a significant effect on most preparedness domain scores. Because this study was observational, we could not tease out the comparative effectiveness of these various programs on preparedness capacities. Nevertheless, these findings indicate that, at least in one state, accreditation had a significant effect on the preparedness capacities of LHDs. Further, these findings suggest that accreditation can be viewed as another tool in the performance improvement toolbox for LHDs.

Non-accredited NC participant LHDs also had higher domain scores than LHDs that had not participated in any performance improvement program. We found no significant differences between the accredited and non-accredited NC LHDs. There are two potential, interrelated explanations for this finding. First, NC has a strong preparedness program that pre-dates September 2011, including statewide resources that have been exercised and deployed numerous times.33 As part of this program, NC LHDs have to meet numerous specific state contract preparedness and other program agreement addenda requirements, regardless of accreditation status, to receive state funding. Thus, as seen in these results, all NC LHDs performed comparably with or higher than the national sample in most preparedness domains, with the exception of Workforce and Volunteers and Plans and Protocols. Second, the NCLHDA program has been in operation for eight years, with publicly available standards, benchmarks, and activities, and participation in the program is mandatory. According to the administrator of the NCLHDA program, accreditation preparation occurs 18–24 months in advance of submission of accreditation documentation to the program (Personal communication, Dorothy Cilenti, DrPH, NCLHDA program, November 2013). At the time of this study, 35 NC LHDs were not accredited using the 18- to 24-month window, and an additional 18–20 LHDs in the non-accredited group were actively preparing for accreditation. Thus, scores for this group may have been affected by preparatory exposure to the program. This finding has implications for future research on the impact of accreditation. It may be difficult to tease out impacts of accreditation on LHD performance, especially with the national rollout of accreditation standards through PHAB.

LHDs that participated in selected comparison programs—PPHR, PHAB beta testing, and the NPHPSP—also had significantly higher scores on all but one domain compared with LHDs with no program participation. Most of these LHDs had participated in PPHR, indicating that this program supports a variety of preparedness capacities. With both the PHAB beta test and NPHPSP standards, including specific preparedness measures, these programs were likely to have an effect on performance across many program areas, including preparedness. Previous research has found that LHDs that participate in these programs tend to have leaders who are champions for performance improvement and quality; participate in multiple improvement efforts, including national efforts; and have a history of evidence-based decision making.30,34 Future research opportunities could include examining the separate effects of these and other performance improvement programs on preparedness, as well as other program measures.

Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. First, this survey was cross-sectional and took measurements at one point in time. Thus, no causal conclusions about observed relationships could be made. Second, data on preparedness levels were self-reported without verification. There was the potential for overreporting, as we provided all responding LHDs with a tailored report that LHDs have indicated they use for benchmarking, strategic planning, and communicating with partners.35 Finally, there was a potential for underreporting of participation in the national performance programs. LHDs may access and use materials from these programs but not be considered program participants. For example, LHDs can use NPHPSP materials but not submit data to the program to be counted as program participants. Presumably, there may be contamination effects of these and other performance improvement programs on all LHDs, including those in our sample that were categorized as having not participated in any program.

CONCLUSION

The results from this study indicate that there is a relationship between LHDs and preparedness scores in NC, where accreditation is mandatory. LHDs from other states that participated in performance programs also scored higher on preparedness domains. Our research examined LHD participation in performance improvement programs from a one-time perspective. Additional research is needed to understand if participation at multiple times and in multiple programs has additional positive effects on LHD performance. Further, it is important to explore for which program areas we should expect to see performance differences and for which LHDs. In the case of this research, NC has a strong preparedness program that affected all NC LHDs. Other programs may be affected to a greater or lesser extent through participation in performance programs.

Continued exploration of these research questions will inform the national public health systems and services research agenda. Further, these explorations can help explain how performance improvement programs can improve public health practice and identify potential intervention strategies to encourage participation in performance programs that are particularly effective.

Footnotes

The authors thank Elizabeth Mahanna, MPH; Michael Zelek, MPH; and Nadya Belenky, MSPH, for their work on this project. The research was carried out by the North Carolina Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Center, which is part of the University of North Carolina (UNC) Center for Public Health Preparedness at the UNC at Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health and was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) grant #1Po1TP000296.

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC. Additional information can be found at http://cphp.sph.unc.edu/ncperrc.

REFERENCE

- 1.Altarum Institute, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and National Coordinating Center for Public Health Services and Systems Research. A national agenda for public health services and systems research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5S1):S72–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Washington: National Academies Press; 1988. The future of public health. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicola RM. Turning Point's National Excellence Collaboratives: assessing a new model for policy and system capacity development. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2005;11:101–8. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200503000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Association of County and City Health Officials. Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (MAPP) framework [cited 2014 Jul 6] Available from: URL: http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/MAPP/framework/index.cfm.

- 5.Corso LC, Lenaway D, Beitsch LM, Landrum LB, Deutsch H. The national public health performance standards: driving quality improvement in public health systems. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16:19–23. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181c02800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bender K, Benjamin G, Fallon M, Jarris PE, Libbey PM. Exploring accreditation: striving for a consensus model. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13:334–6. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000278024.03455.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillen SM, McKeever J, Edwards KF, Thielen L. Promoting quality improvement and achieving measurable change: the lead states initiative. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16:55–60. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181bedb5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roper WL, Baker EL, Jr, Dyal WW, Nicola RM. Strengthening the public health system. Public Health Rep. 1992;107:609–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riley WJ, Bender K, Lownik E. Public health department accreditation implementation: transforming public health department performance. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:237–42. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Update: investigation of bioterrorism-related anthrax, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50(45):1008–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response. Funding and guidance for state and local health departments. 2012 [cited 2013 Feb 8] Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/coopagreement.htm.

- 12.Scutchfield FD, Knight EA, Kelly AV, Bhandari MW, Vasilescu IP. Local public health agency capacity and its relationship to public health system performance. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004;10:204–15. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Association of County and City Health Officials. 2010 national profile of local health departments [cited 2014 Jul 6] Available from: URL: http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/profile/resources/2010report.

- 14.Davis MV, Mays GP, Bellamy J, Bevc CA, Marti C. Improving public health preparedness capacity measurement: development of the local health department preparedness capacities assessment survey. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7:578–84. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duncan WJ, Ginter PM, Rucks AC, Wingate MS, McCormick LC. Organizing emergency preparedness within United States public health departments. Public Health. 2007;121:242–50. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response. Public health preparedness capabilities: national standards for state and local planning. 2012 [cited 2014 Mar 20] Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/capabilities.

- 17.Institute of Medicine. Washington: National Academies Press; 2008. Research priorities in emergency preparedness and response for public health systems: a letter report. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singleton CM, Corso L, Koester D, Carlson V, Bevc CA, Davis MV. Accreditation and emergency preparedness: linkages and opportunities for leveraging the connections. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20:119–24. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182a9dbd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beitsch LM, Thielen L, Mays G, Brewer RA, Kimbrell J, Chang C, et al. The multistate learning collaborative, states as laboratories: informing the national public health accreditation dialogue. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006;12:217–31. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200605000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joly BM, Polyak G, Davis MV, Brewster J, Tremain B, Raevsky C, et al. Linking accreditation and public health outcomes: a logic model approach. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13:349–56. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000278027.56820.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Public Health Accreditation Board. Standards and measures version 1.0. Application period 2011–July 2014. 2011 [cited 2014 Jul 6] Available from: URL: http://www.phaboard.org/wp-content/uploads/PHAB-standards-and-measures-version-1.01.pdf.

- 22.Ingram RC, Bender K, Wilcox R, Kronstadt J. A consensus-based approach to national public health accreditation. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20:9–13. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182a0b8f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.NORC at the University of Chicago. Evaluation of the PHAB beta test: brief reports. Alexandria (VA): Public Health Accreditation Board. 2011. Also available from: URL: http://www.phaboard.org/general/evaluation-of-the-phab-beta-test-brief-report [cited 2013 May 27]

- 24.De Milto L. Princeton (NJ): Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2012. Providing assistance to public health agencies preparing for accreditation. Also available from: URL: http://www.rwjf.org/en/contact-rwjf.html [cited 2014 Jun 27] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis MV, Reed J, Devlin LM, Michalak C, Stevens R, Baker E. The NC accreditation learning collaborative: partners enhancing local health department accreditation. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13:422–6. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000278038.38894.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis MV, Cannon MM, Stone DO, Wood BW, Reed J, Baker EL. Informing the national public health accreditation movement: lessons from North Carolina's accredited local health departments. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1543–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Association of County and City Health Officials. Project Public Health Ready overview [cited 2013 May 31] Available from: URL: http://www.naccho.org/topics/emergency/PPHR/pphr-overview.cfm.

- 28.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Health Resources and Services Administration. Area health resource files (ARF) 2009–2010 [cited 2014 Jul 15] Available from: URL: http://ahrf.hrsa.gov.

- 29.Davis MV, Mahanna E, Joly B, Zelek M, Riley W, Verma P, et al. Creating quality improvement culture in public health agencies. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:98–104. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D'Agostino RB., Jr Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265–81. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mays GP, Halverson PK, Baker EL, Stevens R, Vann JJ. Availability and perceived effectiveness of public health activities in the nation's most populous communities. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1019–26. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mays GP, McHugh MC, Shim K, Perry N, Lenaway D, Halverson PK, et al. Institutional and economic determinants of public health system performance. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:523–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis MV, MacDonald PDM, Cline JS, Baker EL. Evaluation of public health response to hurricanes finds North Carolina better prepared for public health emergencies. Public Health Rep. 2007;122:17–26. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meit M, Infante A, Singer R, Dullabh P, Moore J. Process improvement in health departments: the role of leadership. Presented at the NACCHO Annual 2010 Conference; 2010 Jul 14–16; Washington. Also available from: URL: http://www.naccho.org/events/nacchoannual2010/Uploads/upload/Process-Improvement-in-LHD.pdf [cited 2014 Mar 17] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belenky NM, Bevc CA, Mahanna E, Gunther-Mohr C, Davis MV. Evaluating use of custom survey reports by local health departments. Frontiers. 2013;2 article 4. [Google Scholar]