Abstract

We performed Monte Carlo simulations of batch transformations of hydrophobic compounds using typical numbers of data points, extent of reaction, and measurement error, to identify the most appropriate biotransformation model to describe such data under different conditions. Highly hydrophobic compounds such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dioxins present special challenges for parameterization due to low environmental concentrations and slow biotransformation rates, which result in high sample variability, few samples, and limited substrate concentration range. Four models of varying complexity (zero-order, first-order, Monod, and Best) were fit to simulated data. Various combinations of initial concentration (S0), half saturation concentration (KS), maximum substrate utilization rate (qmax), measurement error, number of data points per batch run, and extent of biotransformation were simulated. One thousand Monte-Carlo runs were performed for each parameter combination, and AICc (Akaike's information criterion corrected for small numbers of data points) was used to determine the most appropriate model. Neither the Best model nor the zero-order model ever produced the lowest AICc for a majority of simulations under any combination of test conditions. With 10% measurement error, the first-order model always outperformed the others. In the case of 1% measurement error with 10 evenly-spaced data points, the Monod model was the better choice when S0>KS and the system was not mass transfer limited  otherwise, the first-order model was indicated. S0 is constrained by the compound's aqueous solubility; therefore, for highly hydrophobic compounds such as PCBs or polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans, a first-order model is likely to fit batch biotransformation data as well or better than a more complicated model.

otherwise, the first-order model was indicated. S0 is constrained by the compound's aqueous solubility; therefore, for highly hydrophobic compounds such as PCBs or polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans, a first-order model is likely to fit batch biotransformation data as well or better than a more complicated model.

Key words: : batch, kinetics, low solubility compounds, model selection, PCBs, PCDD/Fs

Introduction

Batch studies of contaminant transformation are often employed to obtain model parameters for bioremediation remedies. This can be problematic in the case of certain hydrophobic contaminants, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dioxins, for several practical reasons: Transformation rates are slow, limiting the extent of transformation and the number of samples. Difficult sample extractions introduce sample error and also limit the number of samples. Finally, low solubility limits the range of concentrations that can be tested. Because these factors can all impact model identifiability, we investigated whether Monod model parameters could be reliably obtained, given the circumstances of a typical batch study. We also determined whether other model forms might be more appropriate.

Microbial kinetic models

The problem of identifying the appropriate model to relate microbial growth and substrate and substrate utilization with concentration has long been discussed, and many formulations have been proposed, including those by Blackman, Moser, Tessier, and Contois (Shuler and Kargi, 2002). Most often used is the Monod (1949) model, which can be written in terms of specific substrate utilization as follows:

|

where q is the specific substrate utilization rate [Msubstrate/(Mbiomass·T)], qmax is the maximum specific substrate utilization rate, S is substrate concentration [M/L3], and KS is the half-saturation constant [M/L3].

Laboratory studies (chemostat or batch studies) are frequently used to obtain biokinetic parameters. Because of the low aqueous concentrations of hydrophobic contaminants, the microbes consuming them grow slowly. It is possible to study very slowly growing cells using a chemostat: Lin et al. (2009) operated a cell-retaining chemostat initially described by Schrickx et al. (1993) with a solids retention time of 52 days to obtain kinetic data for Geobacter metallireducens. However, chemostats are rarely used in this application because of the resources necessary for long duration operation. If a culture is expected to run for a few years with only intermittent sampling, batch mode is more practical. In fact, laboratory batch studies are preferred to field measurements for parameter estimation in pesticide biodegradation studies (Soulas and Lagacherie, 2001).

Extracting biokinetic parameters from batch data follows directly from Equation (1). In a generalized batch study, the biomass (X) and S vary over time, whereas μmax, KS, and cell yield (Y) and cell death/decay (b) are considered constants. Biomass and substrate concentrations are measured over time. Y is known or can be estimated from fundamental thermodynamic relationships (e.g., Rittmann and McCarty, 2001; Xiao and VanBriesen, 2006), whereas μmax, KS, and b are determined by data fitting. The major factors affecting model fit that have been discussed in the literature are initial substrate concentrations (S0) relative to KS and whether microbial population changes are significant. When fitting the Monod model to batch data, Robinson (1985) observed a high correlation between parameter estimates when the initial substrate concentrations were very high (S0>50 KS) or very low (S0<1/50 KS). At low S relative to KS, the Monod model degenerates to a first-order model, whereas at high S, it approaches zero-order. In the case of low S0, it is difficult to estimate KS and qmax uniquely. Correlations between μmax and KS lead to large standard deviations of both, with the ratio S0/KS determining the relative uncertainty in Monod kinetic parameters (Liu and Zachara, 2001). Huang et al., studying tetrachloroethene dechlorination kinetics, indicate that S0/KS>4 is best for limiting correlation of the Monod parameters and parameter uniqueness/identification, as long as substrate inhibition is not a problem (Huang et al., 2013). The authors suggest an initial study to estimate KS, enabling determination of the optimal S0 for a follow-up study. If KS is relatively high and, therefore, S0>4·KS is not feasible, estimation of Monod parameters may not be possible, and a different model (first order) is suggested.

Extensive literature has discussed cases in which other models fit observed data better than the Monod model. Schmidt et al. (1985), studying cometabolism or multiple substrate supported growth using phenol and glucose, determined that when the growth substrate is at concentrations too low to support growth, the first-order model was appropriate. Simkins and Alexander (1984) studied aerobic benzoate degradation by Pseudomonas sp., examining the effect of both initial relative concentration (S0/KS) and initial biomass. They presented a figure indicating which of the six models (first order, logistic, Monod without growth, logarithmic, Monod with growth, zero-order) is indicated for three levels of S0 (<< KS, ∼KS, and >>KS) and two levels of initial biomass (biomass growth significant or insignificant).

If the biotransformation process is mass transfer limited, the process takes on the characteristics of the mass transfer process, viz., first-order. Similarly, when S0 is small compared to KS, the only data available are from the first-order part of the growth curve, and so the process once again appears to be first-order. Conversely, when S0 >>KS and mass transfer is not limiting, the zero-order model is indicated. The Monod model should be applicable when mass transfer is not limiting and the available S data bracket KS (i.e., when S0>KS but the final concentration Sfinal<KS).

Robinson and Tiedje (1983) indicated that very large errors (>500%) can be introduced in parameter estimates if significant growth occurred in bottles, but was neglected. For scarcely soluble compounds, however, the no-growth assumption is likely acceptable. For example, in the case of reductive dechlorination of PCBs, Bedard et al. (2007) reported a yield of 9×108 cells/μmol Cl− released. If the batch dechlorination test were of a single chlorine removed from a hexachlorobiphenyl congener at aqueous phase saturation (saturation concentrations for hexachlorobiphenyls range from 0.3 to 9.9 μg/L) (Opperhuizen et al., 1988), then, at most 2.5×104 cells/mL of new biomass would be expected. Therefore, in a system where the initial biomass is at least 106 cells/mL, the change in biomass will be negligible. Because dechlorinators are found in anaerobic habitats (with low oxidative stress), usually with very low levels of chlorinated substrates (and hence low potential growth rates), decay of these organisms is expected to be very slow as well. During batch studies of dechlorination, decay is typically assumed to be negligible (e.g., Duhamel and Edwards, 2007).

Model selection based solely on initial concentration and/or whether growth is significant [as indicated by the work of Simkins and Alexander (1984)] overlooks the fact that the number and quality of data points impact model fit and kinetic model selection. With perfect (error-free) data or an infinite number of data points, Monod parameters could be extracted from any dataset (assuming that is the correct model). As measurement error increases and the number of data points decreases, the fit of any model will worsen. Holmberg (1982) used batch degradation simulations with added error to show that the relative standard deviation of the estimates of KS and μmax increased with increasing relative measurement error, decreasing length of the batch simulation, and decreasing sampling frequency (number of data points/length of simulation). The author concluded that, in cases where KS is small or μmax is low, linear forms (zero-order or first-order) should be used to avoid problems with parameter estimation (Holmberg, 1982).

Extension of Monod model for slow mass transfer

One final consideration for highly hydrophobic pollutants, such as PCBs and polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs) is whether mass transfer resistance is significant. The kinetics of desorption from particles and diffusion through the aqueous phase to the bacteria may decrease the availability of the contaminant at the cell surface and decrease the overall biotransformation rate. Best (1955) adapted the Monod equation to take this mass transfer limitation into account by setting the mass transfer from bulk liquid to the cell surface equal to the substrate uptake by the cell. This yields the Best equation [(Eq. (2)], which has been applied to biotransformation of hydrophobic compounds (Bosma et al., 1997; Harms and Bosma, 1997).

|

where k is an exchange constant [L3/T], which, for biological systems, is typically calculated as the product of a surface area [L2] and a mass transfer coefficient [L/T] (Bosma et al., 1997). The authors define a unitless bioavailability number for the Best model:

|

when Bn is small, biotransformation is mass transfer limited, and when it is large, the process is limited by microbial kinetics. Both processes will be significant (and use of the Best model is indicated) when Bn≈1, (Bosma et al., 1997). Diffusive mass transfer is a first-order process, so if a coupled diffusion/bacterial utilization process is mass transfer limited, the overall process should exhibit first-order kinetics. This will occur if k is small relative to the biokinetic parameters (qmax/KS). If mass transfer is not limiting, the Best model simplifies to the Monod model.

Special difficulties in fitting data for hydrophobic substrates

In practice, several factors make it challenging to extract biokinetic parameters from batch biotransformations of highly hydrophobic contaminants. Low aqueous concentrations result in slow transformation rates, measurement difficulties, sorption to biomass, and a limited range of S/KS available for testing.

As biotransformation rates decrease with decreasing substrate concentration, a batch process can theoretically never proceed to completion. Biotransformation of sparingly soluble compounds—particularly weathered contaminants—is slow compared to other processes. This is likely caused by a combination of mass transfer limitation and microbial kinetics. Batch studies of PCDD and PCDF dechlorination in our laboratory often run for a year or longer (e.g., Liu and Fennell, 2007; Krumins et al., 2009), and experiments must be stopped for logistical reasons rather than for reaching some optimal endpoint (from the standpoint of obtaining kinetic data). In that timeframe, typically, 50% or less of the original substrate is transformed. Starting a batch reaction with a lower initial concentration will result in proportionally slower reaction rates, but may be useful for identifying KS. So the initial concentration is limited by the substrate solubility, and final concentration is limited by the extent of biotransformation, which is limited by the time available. As a result, the substrate range available for inspection is limited. KS is often interpreted to represent the (inverse of) the affinity of a microbe for its substrate [although there is no theoretical basis for this (Liu, 2007)]. This suggests that KS for compounds of low bioavailability (e.g., hydrophobic), may be considerably lower than published KS for more soluble compounds. We, therefore, leave open the possibility that for hydrophobic compounds, KS may be quite small and typical batch experimental data might in fact span KS or even come from the zero-order portion of the curve.

A relatively small number of data points can be obtained from batch studies of highly hydrophobic contaminants such as PCBs and PCDD/Fs, because of their low (ppm to ppt) concentrations of environmental concern, sorption, interferences, and difficult quantitation methods. For example, we estimate from our own experience that congener-specific analysis of PCBs, from sample extraction and clean-up through data analysis, requires approximately four person-hours per sample. This limits the number of data points that can practically be obtained. If sampling only the aqueous phase, a large sample volume (hence, a large proportion of a batch culture volume) is needed, also limiting the number of samples that can be collected per batch run.

The analytical techniques available for analysis of highly hydrophobic compounds are relatively imprecise. EPA method 8000B (USEPA, 1996) provides guidance on calibration and quality control for a variety of analytical chromatographic techniques for various analytes, including semivolatiles, PAHs, organochlorine pesticides, and PCBs. It indicates that a laboratory control sample (LCS, a clean matrix spiked with the compound of interest) should be run and recovery should be in the range 70% <LCS<130% for most of these compounds (those for which specific acceptance criteria are not defined). That is, up to 30% error is acceptable in extraction and analysis of laboratory-amended samples. Analysis of chromatograms of historical calibration runs performed using gas chromatography–electron capture detection for our previous work (Krumins et al., 2009) revealed a relative standard deviation of 2.5% for individual congeners for PCB internal standards (standards added to samples after extraction). This suggests that the error of any individual measurement (due to instrument error alone) will be at least 2.5% of the calibration standard amount, whereas the error due to extraction and measurement combined can be up to 30% of the amended amount. Assuming the concentrations of calibration standards and LCS are approximately the same magnitude as the analytes of interest, measurement error could be ∼3–30%.

Which model is most appropriate?

We are interested in determining which model to use for biotransformation of highly hydrophobic compounds such as PCBs and PCDD/Fs in batch studies of reasonable duration with reasonable numbers of samples and sample error. We wish to find the model that has the most information theory justification among this family of models (Best, Monod, first-order, zero-order). Factors that determine applicability include the relative magnitude of S0 to KS, the quantity and quality of available data, and whether mass transfer limitation is significant.

In addition, because the models have different numbers of fit parameters, model selection will affect the degrees of freedom. In this study, we use an information theory approach to explore under what conditions (number of data points, relative measurement error, S0/KS, mass transfer limitation, extent of batch runs) the use of models with more fit parameters (Monod or Best) is justified over simpler models (zero-order, first-order). Akaike's information criterion (AIC) is a commonly used model selection criterion for time series data based on information theory (Motulsky and Christopoulos, 2004). The AICc (AIC corrected for small numbers of data points) is calculated for each model fit of the data using Equation (4):

|

where RSS is the residual sum of squares from the model fit, N is the number of data points fit by the model, and K is the number of fit parameters in the model, plus 1.

When different models are fit to the same dataset, the model with the smallest AICc is most likely to be correct. Thus the AICc provides a method for comparing the suitability of models with varying structure and different numbers of fit parameters.

Methods

MATLAB version 7.5.0 (The Mathworks, Natick, MA) was used to generate Monte Carlo simulations of data for batch biotransformation tests, fit the four different model types to the data, and determine model fits. Because the Best model has the greatest complexity of the family of models tested, and the others can all be considered as special cases of it, a finite difference version of the Best model was used to simulate true substrate concentrations versus time. This approach allowed independent variation of all relevant factors that may influence selection among the four models: the values of KS/S0, qmax/(k·S0), the extent of biotransformation in the batch study, and measurement error, which could not be controlled if using real data. Simulations were performed assuming no growth or decay. A number of evenly-spaced (in time) samples were selected from the generating curve, and data points for model fitting were generated by adding simulated measurement error (randomly drawn from a normal distribution, μ=0, σ=error·S0) to the samples.

The Best, Monod, and first-order models were fit to the simulated data by first selecting an initial guess for the model parameters and running finite difference simulations. Because we assumed constant error variance, the traditional absolute least-squares criterion was used (Saez and Rittmann, 1992). The model parameters were optimized by calculating the sum of squares error (SSE) between the model predictions and all of the simulated data points, and minimizing the SSE using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm (MATLAB function lsqnonlin). The time step for the model simulations was 1/100 of the actual time in the simulation used to generate the data. For the Best model, the initial guesses were the parameters used to generate the biotransformation data (S0, KS, qmax, and k), plus normally distributed random noise with σ=10% of the true parameter value. Similarly, the Monod model was fit using S0, KS, and qmax (plus noise), as starting guesses, and the first-order model was fit using S0 and qmax/KS (plus noise) as an initial guess for the first-order rate. The zero-order model was fit by simply taking a least-squares linear regression of the simulated data versus time. Figure 1 shows one such data simulation and the fits of the four different models.

FIG. 1.

Example generated batch biotransformation curve with model fits. Batch simulation data ( ) generated using Best model with Bn=1 (KS/S0=0.5 and qmax=0.5·k·S0), 10 data points, reaction extent=90%, and measurement error=3% of S0. Least squares fits of Best

) generated using Best model with Bn=1 (KS/S0=0.5 and qmax=0.5·k·S0), 10 data points, reaction extent=90%, and measurement error=3% of S0. Least squares fits of Best  , Monod

, Monod  , first-order

, first-order  , zero-order

, zero-order  , and no activity (

, and no activity ( ). (A) Substrate concentration versus time. (Monod and Best models are nearly indistinguishable at this scale.) (B) Apparent reaction rate (Sn+1−Sn)/(tn+1−tn) versus substrate concentration (Sn+1+Sn)/2.

). (A) Substrate concentration versus time. (Monod and Best models are nearly indistinguishable at this scale.) (B) Apparent reaction rate (Sn+1−Sn)/(tn+1−tn) versus substrate concentration (Sn+1+Sn)/2.

AICc was used to evaluate each model fit using the SSE (after model parameters were optimized), and accounting for the different number of fit parameters for the five models. Initially, 500 runs at each of the 13 levels of KS/S0, spanning 6 orders of magnitude, and 12 levels of qmax/(k·S0) (12 orders of magnitude) were simulated. The extent of reaction (90%), measurement error (σ=0.1·S0), and the number of evenly-spaced data points (10) were not varied. For these simulations, the first-order model outperformed the other models for all combinations of KS/S0 and qmax/(k·S0) (data not shown). We then repeated the simulations with more optimistic levels of measurement error (σ=0.01·S0), and found that optimal model selection depended on KS/S0 and qmax/(k·S0) in the region were both ratios roughly equaled 1. Using the same values for reaction extent, error, and number of data points, a full factorial design was applied to determine the effect of KS/S0 and qmax/(k·S0) on model identifiability. Six levels of both KS (0.031, 0.1, 0.31, 1, 3.1, and 10 ·S0) and qmax (0.031, 0.1, 0.31, 1, 3.1, and 10 ·k·S0) were tested. One thousand Monte Carlo simulations were run at each combination of KS and qmax. Starting with the baseline case of 10 data points, 1% simulated measurement error, and 90% biotransformation extent, sensitivity analyses were performed by changing each of these parameters one at a time. For example, sensitivity to the simulated measurement error was tested by keeping the number of data points (10) and extent (90%) constant, while repeating the baseline experiment with different levels of error (0.25%, 0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, and 5%). Four levels of number of data points (7, 10, 20, and 40) and four levels of batch extent (50%, 70%, 90%, and 99%) were similarly tested. For each simulation, AICc scores were calculated for all four models (zero-order, first-order, Monod, and Best), and the model with the lowest score was determined. The model which had the lowest AICc score in a plurality of the 1,000 simulations for each parameter combination was determined.

Results and Discussion

Model convergence

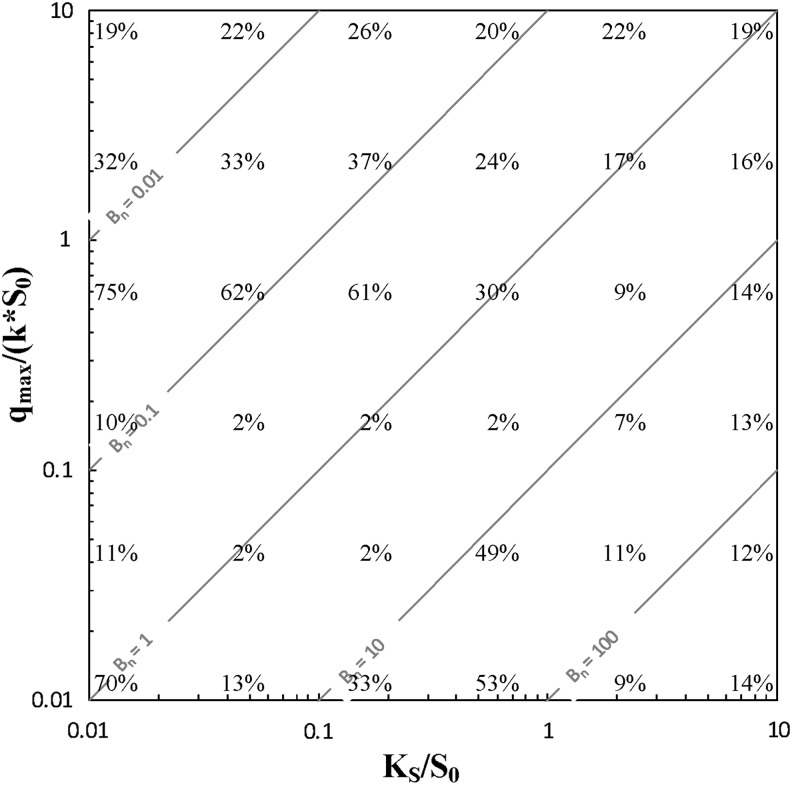

A large proportion of the simulations could not be fit using the Best model: the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm failed to converge in up to 75% of the simulations under certain combinations of KS and qmax, despite the fact that the initial guesses were within 10% of the true parameter values used to generate the simulated data. Seagren et al. (2003) found that initial guesses had a large impact on parameter estimates for simulated batch reactions with Andrews (substrate inhibition) kinetics. For some combinations of true model parameters and initial guesses, model fitting criteria could not be met (nonconvergence). The parameter estimates were closest to the true parameter values when initial guesses were most accurate (within 5% of the true values). In most situations fitting experimental data, initial guesses will not be so close to the final parameter values. For this study comparing different models for batch transformations of hydrophobic compounds, we did not investigate initial guesses with greater than 10% difference from the true values or how these investigate initial guesses might affect model fits or convergence, and ultimately, model identifiability. As one might expect, model fitting of the Best model was most successful when Bn≈1 (Fig. 2). There were no fit failures using the zero-order or first-order models, and nonconvergence using the Monod model was very rare (<0.01% of simulations).

FIG. 2.

Best model nonconvergence. The percentages indicate the percentage of Monte Carlo runs where Levenberg–Marquardt method failed to converge in fitting Best model to simulated data, plotted versus KS/S0 and qmax/k·S0. Baseline case (10 data points, 90% extent of reaction, measurement error=1% of S0). The bioavailability number Bn=k·KS/qmax is overlain for reference. It is suggested that the Best model is most appropriate when Bn≈1 (Bosma et al., 1997), which coincides with the lowest frequency of nonconvergence in fitting the Best model to the data.

Winning models

Since the Best model's predictions are very similar to those of the Monod model (Fig. 1), but at the cost of an additional fit parameter, it rarely had a lower AICc score than the Monod model. Although the Best and zero-order models did occasionally have the lowest AICc score for a given simulation, there was no combination of parameters, for which they had the lowest AICc score, the majority of the time. The choice under the range of parameters we tested, then, was between the first-order and Monod models. Figure 3 shows the results of the Monte Carlo simulations for the baseline case. Its contours represent the percent of simulations in which the first-order model had the lowest AICc score of the tested models, for specific values of KS/S0 and qmax/(k·S0).

FIG. 3.

Contour plot of the occurrence of first-order model having the lowest AICc (Akaike's information criterion corrected for small numbers of data points) score of the five models tested in 1,000 Monte Carlo simulations at each combination of KS/S0 and qmax/k·S0. Baseline case of 10 data points, 90% extent of reaction, measurement error=1% of S0.

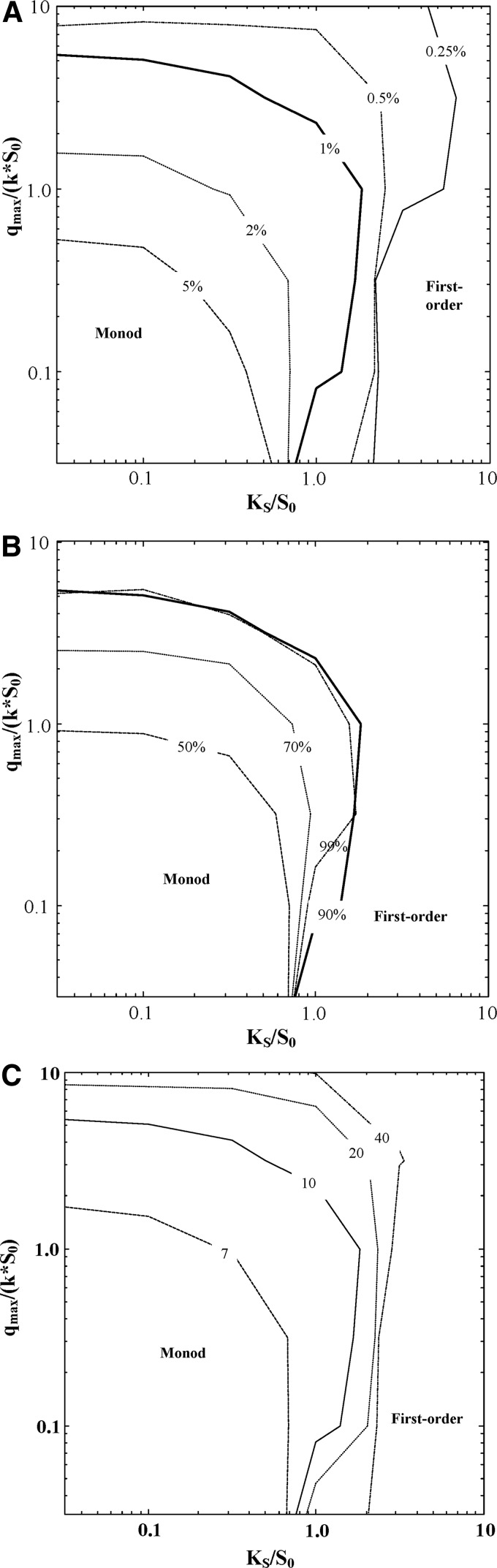

In Fig. 4 we indicate the boundary between the region in KS/S0- qmax/(k·S0) space where the Monod model has the lowest AICc score in a plurality of Monte Carlo simulations (low values of both KS and qmax) from the region where the first-order model is most often preferred (higher values of KS and/or qmax). For the baseline case, the Monod model is preferable when KS<S0 and qmax<(5·k·S0). These boundaries are relatively insensitive to the extent of the batch study, number of data points, or measurement error. For example, at lower levels of error (0.25%), the area in which Monod outperforms the first-order model is KS<3·S0 and qmax<10·k·S0, whereas higher levels of error (5%) result in the Monod being preferred only when KS<0.5·S0 and qmax<0.5·k·S0 (Fig. 4A). Changing the extent of the batch simulation from 99% to 50% completion (Fig. 4B) has minimal effect on the KS effect on model selection, but decreases the criterion on qmax to qmax<k·S0. There is a diminishing effect of the number of data points: increasing from 7 to 10 samples increases the space where the Monod model is preferable from KS<0.7·S0 to KS<1.0·S0 and qmax<2·k·S0 to qmax<5·k·S0, whereas adding another 30 samples enlarges the space only to KS<2·S0 and qmax<10·k·S0 (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Contour lines for first-order model achieving the lowest AICc score in 50% of the Monte Carlo simulations. Because (in this region) the Best, zero-order, and no activity models were only very rarely preferred, this contour indicates the transition between where the first-order model most frequently exhibited the lowest AICc score and where the Monod model most often did. To the lower left of the contour line (lower KS/S0 and qmax/(k·S0) values), the Monod model most often has the lowest AICc score; above and to the right of the line, the first-order model most frequently had the lowest score. All plots include the baseline case (10 data points, 90% extent of reaction, measurement error=1% of S0). (A) Sensitivity to measurement error  . (B) Sensitivity to extent of batch biotransformation

. (B) Sensitivity to extent of batch biotransformation  . (C) Sensitivity to the number of data points

. (C) Sensitivity to the number of data points  .

.

In light of these findings, practitioners should check that parameters determined from fitting a Monod model to batch data conform to the following requirements:

|

|

The criterion for KS is similar to the nonquantitative results of Simkins and Alexander (1984), who found that they were able to fit the Monod model in no-growth cases when S0≥2.5·KS, and with the results of Huang et al. (2013) who determined that S0≥4·KS minimized Monod parameter uncertainty. In our simulations, when S0 was less than KS (found from runs with higher S0, such that KS could be determined), the Monod model was inapplicable. S0 cannot exceed the aqueous solubility of the compound. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we have not found any reference in the literature to a compound with KS that was greater than its aqueous solubility. The lowest published KS values we have found for any organic compound are for toluene (CSat=5 mM) degradation under aerobic conditions: 0.64 μM for Pseudomonas fluorescens K3-2 (Shreve and Vogel, 1993) and 1 μM for Ps. putida R1 (Pedersen et al., 1997). The compound with the highest KS relative to CSat that we could find is for aerobic biodegradation of 1-methylnaphthalene (CSat=200 μM, KS=37 μM) (Knightes and Peters, 2003); the authors were unable to fit the Monod model to any of the higher molecular weight PAHs they studied. Liu (2007) found that dechlorination of 1,2,3,4-TeCDD in sediment slurries followed first-order kinetics, but by combining data from many experiments, she was able to estimate KS (291 μM) for this process. Analytical limitations prevented the measurement of aqueous phase TeCDD, so this half-saturation concentration is on the whole sediment slurry rather than an aqueous basis. To our knowledge there are no published estimates of aqueous phase KS for PCDD/F or PCB dechlorination.

The exchange constant k depends on the physical and chemical properties of the system under study. For the case of diffusion through static water to a spherical particle,

|

where D is the substrate diffusivity in water [L2/T] and r is the particle radius [L].

This formulation of k is appropriate if the primary constraint on mass transfer is diffusion from the bulk liquid to the cell, rather than desorption from surfaces or diffusion through pores if soil or sediment is present. Based on the approximation of Wilke and Chang (1955), the diffusivities (D) for PCBs and PCDDs are in the range 2.2–2.5×10−9 m2/s. It follows from Equation (7) that, for a cell of diameter 500 nm, the approximate size of Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195 (from Maymo-Gatell et al., 1997), k≈7.5×10−15 m3/s. Table 1 presents the aqueous solubilities of selected PCBs and PCDDs, which also approximate the upper limit of KS that would be valid for a fit of the Monod model [(Eq. (5)]. The table also indicates the maximum qmax and μmax satisfying Equation (6), assuming diffusive mass transfer [Eq. (7)]. Thus, for a batch biotransformation of HxCDF, we suggest that a first-order model should be selected unless the Monod parameters are found to be KS<8 pM and μmax<8.5 year−1.

Table 1.

Upper Limits to KS and qmax for Applying Monod Model, Selected Polychlorinated Biphenyl and Polychlorinated Dibenzo-p-Dioxins and Dibenzofurans Congeners

| KSa | qmaxb | μmaxc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg/L | nM | μmol/cell/s | molecule/cell/s | day−1 | |

| 2,4,5-Trichlorobiphenyl | 110 | 430 | 1.6×10−11 | 9.7×106 | 1,300 |

| 2,3,4,5-Tetrachlorobiphenyl | 16 | 55 | 2.1×10−12 | 1.2×106 | 160 |

| 2,2′,4,4′,6,6′-Hexachlorobiphenyl | 2.8 | 7.8 | 2.9×10−13 | 1.8×105 | 23 |

| 2,7-Dichlorodibenzo-p-dioxin | 4.1 | 16 | 6.1×10−13 | 3.6×105 | 47 |

| 1,2,3,4,7,8,-Hexachlorodibenzofuran | 0.0030 | 0.0079 | 3.0×10−16 | 180 | 0.023 |

| 1,2,3,4,6,9-Hexachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin | 0.0012 | 0.0031 | 1.2×10−16 | 69 | 0.0089 |

| Octachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin | 0.00023 | 0.0005 | 1.9×10−17 | 11 | 0.0015 |

Based on Equation (7), KS must be less than the aqueous solubility. Solubilities of PCBs from Shiu et al. (1997) and for PCDD/Fs from Oleszek-Kudlak et al. (2007).

The maximum qmax that is consistent with the constraint of Equation (8), assuming mass transfer is diffusion limited from bulk liquid to a 500 nm spherical cell [Eq. (9)].

Based on qmax and yield on dechlorination of 9×108 cells/μmol of chlorine removed (Bedard et al., 2007).

PCBs, polychlorinated biphenyls; PCDD/Fs, polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans.

Conclusions

While several models are available to simulate microbial kinetics, simpler models are often indicated for analyzing batch kinetic data for hydrophobic contaminants, because of limited quantity and quality of data and the limited range of substrate concentrations that can be tested. Low solubilities put an upper limit on the concentrations that can be tested and increase the likelihood that the biotransformation process will be mass transfer limited, two factors that favor a first-order model. Analytical challenges usually lead to relatively few data points with high variability, also indicating use of the simpler (first-order) model.

We performed Monte Carlo simulations of batch transformations of hydrophobic compounds using typical numbers of data points, extent of reaction, and measurement error, and find that use of a first-order model is indicated in most cases. With 10% measurement error, the first-order model outperformed the Monod model in every case. Even with optimistic measurement error of 1%, the Monod model is likely to be appropriate only if KS<S0 and qmax<5·k·S0. The first criterion can be interpreted to mean KS should be less than the aqueous solubility of the compound if the Monod model is to be successfully applied. This suggests that, if the Monod model is to be applied to any of the compounds listed in Table 1 (PCBs with three or more chlorine substituents, PCDD/Fs with two or more chlorines), KS would have to be lower than the lowest published value we could find for any organic molecule. The second criterion places an upper limit on specific substrate utilization and growth rate, based on the mass transfer regime of the system. The high upper limits on μmax for more soluble compounds in Table 1 suggest that mass transfer limitation is not likely to affect model selection except, perhaps, for PCDD/Fs with six or more chlorines in quiescent systems where mass transfer is controlled by diffusion from the bulk liquid to the cell.

This work shows that the use of the Monod model is rarely justified for use in batch dechlorination studies of very hydrophobic compounds, because of stringent requirements on solubility and measurement error for any model to outperform the first order model. Batch studies are often performed, models fitted, and parameters extracted with the intent of applying the data to pilot or field scale systems. Selection of a more complicated model implies greater knowledge about the system than may be supported by the quantity and quality of available data, although it is beyond the scope of this work to speculate on the impact of inappropriate model selection on predicting outcomes in the field.

Acknowledgments

Partial support for this project was provided by a grant from the Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP) Project number ER-1492.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Bedard D.L., Ritalahti K.M., and Loffler F.E. (2007). The Dehalococcoides population in sediment-free mixed cultures metabolically dechlorinates the commercial polychlorinated biphenyl mixture Aroclor 1260. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best J.B. (1955). The inference of intracellular enzymatic properties from kinetic data obtained on living cells. I. Some kinetic considerations regarding an enzyme enclosed by a diffusion barrier. J. Cell. Comp. Physiol. 46, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosma T.N., Middeldorp P.J., Schraa G., and Zehnder A.J. (1997). Mass transfer limitation of biotransformation: quantifying bioavailability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 31, 248 [Google Scholar]

- Duhamel M., and Edwards E.A. (2007). Growth and yields of dechlorinators, acetogens, and methanogens during reductive dechlorination of chlorinated ethenes and dihaloelimination of 1, 2-dichloroethane. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms H., and Bosma T.N.P. (1997). Mass transfer limitation of microbial growth and pollutant degradation. J. Indus. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 18, 97 [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg A. (1982). On the practical identifiability of microbial growth models incorporating Michaelis-Menten type nonlinearities. Math. Biosci. 62, 23 [Google Scholar]

- Huang D., Lai Y., and Becker J.G. (2013). Impact of initial conditions on extant microbial kinetic parameter estimates: application to chlorinated ethene dehalorespiration. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knightes C.D., and Peters C.A. (2003). Aqueous phase biodegradation kinetics of 10 PAH compounds. Environ. Eng. Sci. 20, 207 [Google Scholar]

- Krumins V., Park J.W., Son E.K., Rodenburg L.A., Kerkhof L.J., Häggblom M.M., and Fennell D.E. (2009). PCB dechlorination enhancement in Anacostia River sediment microcosms. Water Res. 43, 4549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B., Westerhoff H.V., and Röling W.F. (2009). How Geobacteraceae may dominate subsurface biodegradation: physiology of Geobacter metallireducens in slow-growth habitat-simulating retentostats. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F. (2007). Microbial dechlorination of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans: pathways, kinetics and environmental implications [Dissertation]. Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ, p. 189 [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. (2007). Overview of some theoretical approaches for derivation of the Monod equation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 73, 1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., and Zachara J.M. (2001). Uncertainties of Monod kinetic parameters nonlinearly estimated from batch experiments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35, 133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., and Fennell D.E. (2007). Dechlorination and detoxification of 1,2,3,4,7,8-hexachlorodibenzofuran by a mixed culture containing Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maymo-Gatell X., Chien Y., Gossett J.M., and Zinder S.H. (1997). Isolation of a bacterium that reductively dechlorinates tetrachloroethene to ethene. Science 276, 1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monod J. (1949). The growth of bacterial cultures. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 371 [Google Scholar]

- Motulsky H., and Christopoulos A. (2004). Fitting Models to Biological Data Using Linear and Nonlinear Regression: A Practical Guide to Curve Fitting. New York: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Oleszek-Kudlak S., Shibata E., and Nakamura T. (2007). Solubilities of selected PCDDs and PCDFs in water and various chloride solutions. J. Chem. Eng. Data 52, 1824 [Google Scholar]

- Opperhuizen A., Gobas F.A.P., Van der Steen J.M., and Hutzinger O. (1988). Aqueous solubility of polychlorinated biphenyls related to molecular structure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 22, 638 [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen A.R., Møller S., Molin S., and Arvin E. (1997). Activity of toluene‐degrading Pseudomonas putida in the early growth phase of a biofilm for waste gas treatment. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 54, 131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittmann B.E., and McCarty P.L. (2001). Environmental Biotechnology: Principles and Applications. New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 754 [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J.A. (1985). Determining microbial kinetic parameters using nonlinear regression analysis. Advantages and limitations in microbial ecology. Adv. Microb. Ecol. 8, 61 [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J.A., and Tiedje J.M. (1983). Nonlinear estimation of Monod growth kinetic parameters from a single substrate depletion curve. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45, 1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez P.B., and Rittmann B.E. (1992). Model-parameter estimation using least squares. Water Res. 26, 789 [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S.K., Simkins S., and Alexander M. (1985). Models for the kinetics of biodegradation of organic compounds not supporting growth. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 50, 323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrickx J.M., Krave A.S., Verdoes J.C., Van den Hondel C.A., Stouthamer A.H., and Van Verseveld H.W. (1993). Growth and product formation in chemostat and recycling cultures by Aspergillus niger N402 and a glucoamylase overproducing transformant, provided with multiple copies of the glaA gene. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139, 2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seagren E.A., Kim H., and Smets B.F. (2003). Identifiability and retrievability of unique parameters describing intrinsic Andrews kinetics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 61, 314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu W.Y., Wania F., Hung H., and Mackay D. (1997). Temperature dependence of aqueous solubility of selected chlorobenzenes, polychlorinated biphenyls, and dibenzofuran. J. Chem. Eng. Data 42, 293 [Google Scholar]

- Shreve G.S., and Vogel T.M. (1993). Comparison of substrate utilization and growth kinetics between immobilized and suspended Pseudomonas cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 41, 370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuler M.L., and Kargi F. (2002). Bioprocess Engineering. New York: Prentice Hall [Google Scholar]

- Simkins S., and Alexander M. (1984). Models for mineralization kinetics with the variables of substrate concentration and population density. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 47, 1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulas G., and Lagacherie B. (2001). Modelling of microbial degradation of pesticides in soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 33, 551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) (1996). SW-846 Test Methods for Evaluating Solid Waste, Physical/Chemical Methods, Method 8000B, Determinative Chromatographic Separations. Washington, DC: USEPA [Google Scholar]

- Wilke C.R., and Chang P.I.N. (1955). Correlation of diffusion coefficients in dilute solutions. AIChE J. 1, 264 [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J., and VanBriesen J.M. (2006). Expanded thermodynamic model for microbial true yield prediction. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 93, 110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]