Abstract

A nitrile-hydrolysing bacterium, identified as Isoptericola variabilis RGT01, was isolated from industrial effluent through enrichment culture technique using acrylonitrile as the carbon source. Whole cells of this microorganism exhibited a broad range of nitrile-hydrolysing activity as they hydrolysed five aliphatic nitriles (acetonitrile, acrylonitrile, propionitrile, butyronitrile and valeronitrile), two aromatic nitriles (benzonitrile and m-Tolunitrile) and two arylacetonitriles (4-Methoxyphenyl acetonitrile and phenoxyacetonitrile). The nitrile-hydrolysing activity was inducible in nature and acetonitrile proved to be the most efficient inducer. Minimal salt medium supplemented with 50 mM acetonitrile, an incubation temperature of 30 °C with 2 % v/v inoculum, at 200 rpm and incubation of 48 h were found to be the optimal conditions for maximum production (2.64 ± 0.12 U/mg) of nitrile-hydrolysing activity. This activity was stable at 30 °C as it retained around 86 % activity after 4 h at this temperature, but was thermolabile with a half-life of 120 min and 45 min at 40 °C and 50 °C respectively.

Keywords: Acrylic acid, Biotransformation, Isoptericola variabilis, Nitriles

Introduction

Nitriles (general formula, RC ≡ N) are widespread in the environment due to their excessive use in industries. Nitriles are toxic in nature, but can be hydrolysed to corresponding less-toxic and valuable carboxylic acids either by nitrilase (EC 3.5.5.1), or by nitrile-hydratase (EC 4.2.1.84) and amidase (EC 3.5.1.4). Nitrilases have been reported in a variety of microbes including Alcaligenes [1], Bacillus [2], Burkholderia [3], Labrenzia [4], Pseudomonas [5], Pyrococcus [6] and Rhodococcus [7]. In spite of many nitrilases reported in literature, the quest for their new sources has never ended. Owing to their capability of environment friendly transformation of nitriles, nitrilases are employed for the synthesis of pharmaceuticals and commodity chemicals [8]. These versatile biocatalysts have potential biotechnological applications like carboxylic acid production, wastewater treatment, herbicide degradation and polymer surface modification [9]. Bioconversion of acrylonitrile to acrylic acid is a better option than its chemical synthesis, which has drawbacks of high temperature conditions, side reactions, environmental pollution and high cost [7]. Acrylic acid is used in the manufacture of paint formulations, paper coatings, polishes, adhesives, acrylic esters, flocculants, etc. [7, 10].

In this paper, we report on the isolation, identification and media optimization for nitrile-hydrolysing activity of an isolate identified as I. variabilis RGT01.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Media

All nitriles, acrylamide and acrylic acid were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Butyronitrile and propionitrile were purchased from Merck (Germany) and Himedia (India) respectively. All reagents were of analytical grade. The Minimal Salt Medium (MSM) contained following in g/l of deionised water: Na2HPO4.2H2O, 2; KH2PO4, 2; MgCl2.6H2O, 0.1; NH4Cl, 0.1. The final pH of the medium was 7.0. Autoclaving was done at 121 °C for 15 min. Nitriles were added aseptically to the medium after autoclaving.

Screening and Cultivation of Nitrile-Hydrolysing Bacteria

Industrial effluent from Samana, Punjab, India; and soil samples from Churu, Rajasthan, India; Solan, Himachal Pradesh, India were collected. Soil sample (1 g) or effluent (1 ml) was added to 50 ml MSM supplemented with 25 mM acrylonitrile and incubated at 30 °C for 72 h under shaking conditions (orbital, 200 rpm). One ml of the culture was transferred to 50 ml of fresh medium and incubated under similar conditions. This step was repeated once again and an aliquot of the culture was spread on MSM agar plates supplemented with 25 mM acrylonitrile and incubated at 30 °C to obtain morphologically distinct colonies, which were streaked onto the fresh medium to obtain a pure culture.

The isolates obtained were streaked on MSM plates containing one of the four nitriles (acrylonitrile, propionitrile, butyronitrile and benzonitrile) at a final concentration of 25 mM. Concentration of the nitriles was increased serially up to 500 mM. The bacterial colonies growing on MSM plates supplemented with nitriles (500 mM, final concentration) were further selected for shake flask studies.

A seed culture was prepared by inoculating a single colony of the bacterial isolate into 100 ml Erlenmeyer flask containing 20 ml nutrient broth (NB), and incubated under shaking conditions (orbital, 200 rpm) at 30 °C, till OD600nm reached 0.4–0.6 (≈ 3x 108 cells per ml). One ml of seed culture was transferred to a 250 ml flask containing 49 ml of MSM supplemented with required nitrile concentration (50–200 mM). The flasks were incubated at 30 °C under shaking conditions (orbital, 200 rpm) for 120 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C.

Conventional physiological and biochemical characterization tests were carried out as described in Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology [11]. RGT01 was identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing technique at IGIB, New Delhi, India.

Enzyme Assay Using Resting Cells

The cell pellet was washed with 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and suspended in the same buffer [30 mg wet pellet (≈ 4.8 mg dry weight) in 1 ml of buffer, having OD660nm ≈ 9.0]. Nitrile-hydrolysing activity was measured by phenol-hypochlorite method [12]. One ml reaction mixture contained 945/940 μl potassium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0), 50 μl cell suspension (1 × 107 cells) and 5/10 μl nitrile (10 M prepared in methanol) (final conc. 50 or 100 mM). Enzyme control and substrate control were also taken into consideration. The reaction was carried out at 30 °C in a water bath for 15 min. One unit of the enzyme activity was defined as the amount of cells that hydrolysed the nitrile to release one micromole of ammonia per minute under standard assay conditions. Weight of wet cells in milligrams was used for the assay.

Optimization of Culture Conditions for Maximal Production of Nitrile-Hydrolysing Activity by I. variabilis RGT01

Nutrient rich media were tested for growth and activity production. The effect of various carbon sources/metal ions/nitriles/ε-caprolactam on growth and nitrile-hydrolysing activity by I. variabilis RGT01 was studied. All factors were studied by changing one factor at a time.

Substrate Specificity of Nitrile-Hydrolysing Activity of I. variabilis RGT01

To study substrate specificity of nitrile-hydrolysing activity of I. variabilis RGT01, a wide range of nitriles (listed in Table 4) at a concentration of 50 mM was used.

Table 4.

Substrate specificity of nitrile-hydrolysing activity of I. variabilis RGT01

| Nitrile (50 mM) | Nitrile-hydrolysing activity (U/mg) |

|---|---|

| Aliphatic nitriles | |

| Saturated nitriles | |

| Acetonitrile | 6.93 ± 0.011 |

| Propionitrile | 4.86 ± 0.16 |

| Butyronitrile | 1.81 ± 0.12 |

| Valeronitrile | 1.63 ± 0.012 |

| Isobutyronitrile, Isovaleronitrile, Allyl cyanide | ND |

| Unsaturated nitrile | |

| Acrylonitrile | 2.04 ± 0.017 |

| Dinitriles | |

| Iminodiacetonitrile, Adiponitrile, Glutaronitrile, Succinonitrile, Malononitrile | ND |

| Aromatic nitriles | |

| Benzonitrile | 1.02 ± 0.010 |

| 4-Aminobenzonitrile | ND |

| m-Tolunitrile | 0.62 ± 0.011 |

| Arylacetonitriles | |

| Mandelonitrile, 4-Aminobenzyl cyanide | ND |

| 4-Methoxyphenyl acetonitrile | 5.19 ± 0.009 |

| Phenoxyacetonitrile | 1.52 ± 0.008 |

| Heterocyclic nitrile | |

| Indole 3-acetonitrile | ND |

ND not detected

Thermostability and pH Stability of Nitrile-Hydrolysing Activity of I. variabilis RGT01

Resting cells were suspended (30 mg/ml) in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and were incubated at different temperatures (30 °C, 40 °C and 50 °C) and at different pH values (6.5, 7.0, 7.5 and 8.0). Samples (200 μl) were withdrawn after every half an hour. To the cell suspension, 50 mM acrylonitrile (from 1 M stock prepared in methanol) was added and incubated at 30 °C. The reaction was stopped after 15 min with the addition of 200 μl of 0.1 M HCl and the amount of acrylic acid formed was determined by phenol-hypochlorite method [12]. Residual activity (RA) was calculated in accordance with the activity at 0 h.

Biotransformation of Acrylonitrile Using Resting Cells

Resting cell suspensions were prepared by suspending the cell pellet in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) to get a concentration of 300 mg/ml. The reaction mixture (10 ml) consisted of 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 2 mM acrylonitrile and a final resting cell concentration of 30 mg/ml. The reaction was performed at 30 °C for 2 h under shaking conditions (orbital, 200 rpm); cells were removed from the reaction mixture by centrifugation at 12000xg for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant obtained was then analyzed by HPLC.

Analytical Methods

HPLC (LC-20AD; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm particle size; Spincotech, India) at a flow rate of 1 ml/minute with a solvent system of HPLC-grade water and acetonitrile (70:30, v/v) in combination with 0.05 % (v/v) formic acid was employed. The UV detector set at a wavelength of 210 nm was used to detect the presence of acrylic acid and acrylamide.

Results and Discussion

Selection and Identification of a Nitrile-Utilizing Strain

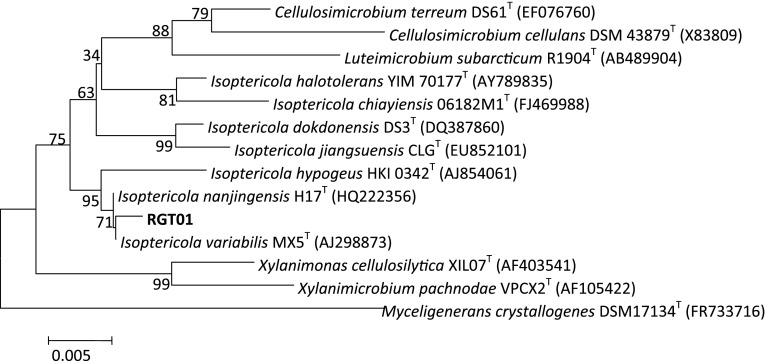

Using enrichment culture technique, 30 bacterial isolates having nitrile-hydrolysing activity were isolated (data not shown). After primary screening on MSM agar plates supplemented with different nitriles (500 mM, final concentration), 24 bacterial cultures were selected for shake flask studies. One isolate, RGT01 exhibited good growth on various nitrile substrates like acrylo-, propio-, butyro- and benzo- nitrile and was used for further studies. Cells of RGT01 were small rods, non-motile, positive for Gram-staining and catalase; and negative for urease, arginine dihydrolase, ornithine decarboxylase, lysine decarboxylase, phenylalanine deaminase, indole production and Voges-Proskauer test. According to its 16S rDNA sequence (940 bp), isolate RGT01 was found to be 99 % identical with the sequence of Isoptericola variabilis (GenBank accession no. AJ298873) by examining the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1). The sequence was deposited in the GenBank database with accession no. KF135213. The result of the phylogenetic analysis was consistent with that of the phenotypic tests. Therefore, isolate RGT01 was identified as a strain of I. variabilis and named I. variabilis RGT01. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the presence of nitrile-hydrolysing activity in the genus Isoptericola. Till date, members of this genus are reported to have only cellulolytic [13] and chitin-degrading activities [14].

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree for I. variabilis RGT01 and related organisms based on the 16S rDNA sequences. Evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbour-Joining method. Numbers in parentheses are accession numbers of published sequences. The evolutionary distances were computed using Kimura 2-parameter method and were conducted in MEGA5. Bootstrap values were based on 1,000 replicates

Effect of Different Media/Inducers on Nitrile-Hydrolysing Activity

Though, all nutrients rich media like nutrient broth, brain–heart infusion broth, terrific broth etc. supported the growth of I. variabilis RGT01, but significant nitrile-hydrolysing activity was observed only in MSM supplemented with 200 mM acrylonitrile (Table 1). Very little or no nitrile-hydrolysing activity by I. variabilis RGT01 in the nutrient-rich environment indicated the strong possibility of production of the enzyme responsible for nitrile hydrolysis under stress conditions.

Table 1.

Growth and nitrile-hydrolysing activity of I. variabilis RGT01 in different media

| Medium + acrylonitrile (200 mM) | Biomass (mg dcw/ml culture) | Acrylonitrile (100 mM) hydrolysing activity (U/mg) |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrient broth | 1.78 ± 0.19 | ND |

| Brain–heart infusion broth | 1.34 ± 0.16 | 0.75 ± 0.12 |

| Terrific broth | 1.93 ± 0.032 | ND |

| MSM | 0.118 ± 0.011 | 1.81 ± 0.15 |

| MSM + FeSO4.7H2O (0.001 %, w/v) | 0.101 ± 0.012 | 0.68 ± 0.009 |

| MSM + CoCl2.6H2O (0.001 %, w/v) | 0.098 ± 0.023 | 1.02 ± 0.034 |

| MSM + ε-Caprolactam (0.1 %, w/v) | 0.120 ± 0.008 | 1.67 ± 0.02 |

Nitrile-hydrolysing activity was absent in medium devoid of inducers

ε-Caprolactam (0.1 %) was used as an inducer while acrylonitrile (final conc. 100 mM) was used as substrate

dcw dry cell weight, ND not detected

Most nitrilases are induced by nitriles, amides and carboxylic acids [9]. In Rhodococcus rhodochrous J1, nitR was found to be required for isovaleronitrile-dependent induction of nitrilase synthesis [15]. Our experiments also indicated inducible nature of nitrile-hydrolysing activity like many nitrilases reported in literature [9]. However, there are also reports on the constitutive nature of nitrilases as observed in Bacillus subtilis [2] and in Rhodococcus ruber [7]. Choice of inducer may affect the substrate specificity of nitrilase [16, 17]. After confirming that the nitrile-hydrolysing activity was produced only in the presence of the inducer and ruling out any constitutive expression of the enzyme, the effect of different inducers on substrate specificity was studied. The host range of nitrile-hydrolysing activity in the presence of a single inducer is listed in Table 2. Using different inducers, there was a change in the substrate specificity. Presence of more than one nitrilase might be responsible for this trend. It is possible that different substrates led to the induction of different nitrilases. There are reports in literature mentioning the occurrence of two types of nitrilases in the same organism [18–20]. Acetonitrile was finally chosen as the inducer for the cultivation, due to its cheaper price and good effectivity than other inducers. It was found to act as an efficient inducer for nitrilases of Pseudomonas putida [5] and Rhodobacter sphaeroides [21]. MSM supplemented with 50 mM acetonitrile, an incubation temperature of 30 °C with 2 % v/v inoculum, at 200 rpm and incubation of 48 h was found to be the optimal condition for maximum production (2.64 ± 0.12 U/mg) of nitrile-hydrolysing activity by I. variabilis RGT01 (Fig. 2). The logarithmic phase of growth was concomitant with the production of nitrile-hydrolysing enzyme. In literature, acrylonitrile-hydrolysing activities of various strains were: Arthrobacter nitroguajacolicus−2.02 U/mg dcw [10], Rhodococcus sp.−1.22 U/mg dcm [16] and Alcaligenes faecalis−0.04 U/mg wet cell weight [17].

Table 2.

Effect of different inducers on growth and nitrile-hydrolysing activity of I. variabilis RGT01

| Inducer (50 mM) | Biomass (mg dcw/ml culture) | Nitrile-hydrolysing activity (U/mg) with substrates (100 mM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | Acrylonitrile | Propionitrile | Butyronitrile | Benzonitrile | ||

| Acetonitrile | 0.46 ± 0.03 | 4.19 ± 0.14 | 2.64 ± 0.12 | 3.14 ± 0.18 | 2.56 ± 0.01 | 1.31 ± 0.02 |

| Acrylonitrile | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 2.38 ± 0.12 | 2.05 ± 0.014 | 1.86 ± 0.13 | 1.58 ± 0.007 | 0.58 ± 0.03 |

| Propionitrile | 0.54 ± 0.05 | 0.89 ± 0.06 | ND | 4.80 ± 0.12 | 1.62 ± 0.006 | ND |

| Butyronitrile | 0.56 ± 0.023 | ND | 1.18 ± 0.02 | 1.55 ± 0.15 | 2.45 ± 0.04 | ND |

| Benzonitrile | 0.13 ± 0.012 | ND | 0.89 ± 0.14 | 0.58 ± 0.007 | 0.95 ± 0.12 | 1.97 ± 0.15 |

dcw dry cell weight, ND not detected

Fig. 2.

Cell growth and nitrile-hydrolysing activity of I. variabilis RGT01 in MSM supplemented with acetonitrile (50 mM)

ε-Caprolactam (0.1 %, w/v) reported to be a hyper-inducer of nitrilase in Rhodococcus rhodochrous J1 [22], did not cause any enhancement in the enzyme production. The addition of Fe2+ and Co2+ ions (required for the active expression of nitrile-hydratase enzyme) in minimal medium showed no significant effect on the nitrile-hydrolysing activity. It might be due to the presence of nitrilase enzyme in the I. variabilis RGT01 which is not a metallo-protein [6].

Effect of Various Carbon Sources on Nitrile-Hydrolysing Activity

Carbon sources may affect growth and nitrile-hydrolysing activity. So their effect was tested for growth as well as enzyme production (Table 3). Presence of simple sugars such as glucose, sucrose, fructose and maltose (final concentration−1.0 %) in MSM increased the growth of I. variabilis, but resulted in diminished nitrile-hydrolysing activity. Glucose and other hexoses are well known to repress microbial enzymes which are responsible for the catabolism of carbon compounds [23]. Whereas, use of carbon sources like lactose, starch, glycerol and sodium acetate lead to no nitrile-hydrolysing enzyme production.

Table 3.

Effect of various carbon sources on growth and nitrile-hydrolysing activity by I. variabilis RGT01

| C source (1.0 %, w/v) | Biomass (mg dcw/ml) | Acrylonitrile (50 mM) hydrolysing activity (U/mg) |

|---|---|---|

| None | 0.46 ± 0.03 | 2.05 ± 0.19 |

| Sucrose | 0.89 ± 0.012 | 0.16 ± 0.03 |

| Maltose | 0.78 ± 0.016 | 0.89 ± 0.13 |

| Lactose | 0.73 ± 0.01 | ND |

| Fructose | 0.81 ± 0.013 | 0.21 ± 0.02 |

| Glucose | 0.76 ± 0.018 | 0.26 ± 0.03 |

| Mannitol | 0.82 ± 0.017 | 0.7 ± 0.12 |

| Starch | 0.81 ± 0.015 | ND |

| Glycerol | 0.88 ± 0.019 | ND |

| Sodium acetate | 0.29 ± 0.005 | ND |

I. variabilis RGT01 was cultivated in MSM supplemented with 50 mM acetonitrile and a single carbon source (1.0 %, w/v)

dcw dry cell weight, ND not detected

Substrate Specificity of Nitrile-Hydrolysing Activity

I. variabilis RGT01 exhibited broad substrate specificity, as it could hydrolyse five aliphatic nitriles, two aromatic nitriles and two arylacetonitriles (Table 4). With saturated aliphatic mononitriles, the shorter the chain length, the greater the rate of hydrolysis was observed. The enzyme activity toward nitriles of shorter chain length suggested that a more compact structure may have a better access or affinity for the active site of the enzyme. The highest activity was observed with acetonitrile, followed by propionitrile, acrylonitrile, butyronitrile and valeronitrile. However, it showed no activity with branched substrates like isobutyronitrile and isovaleronitrile. In case of benzonitrile, substitution at the meta position by a methyl group decreased the enzyme activity; whereas at the para position by the amino group, lead to complete loss of the enzyme activity. Substitution at the para position by methoxy group on the phenyl ring increased the enzyme activity, whereas by most strong electron donating amino group lead to no activity. In case of arylacetonitriles, 4-Methoxyphenyl acetonitrile proved to be the best substrate.

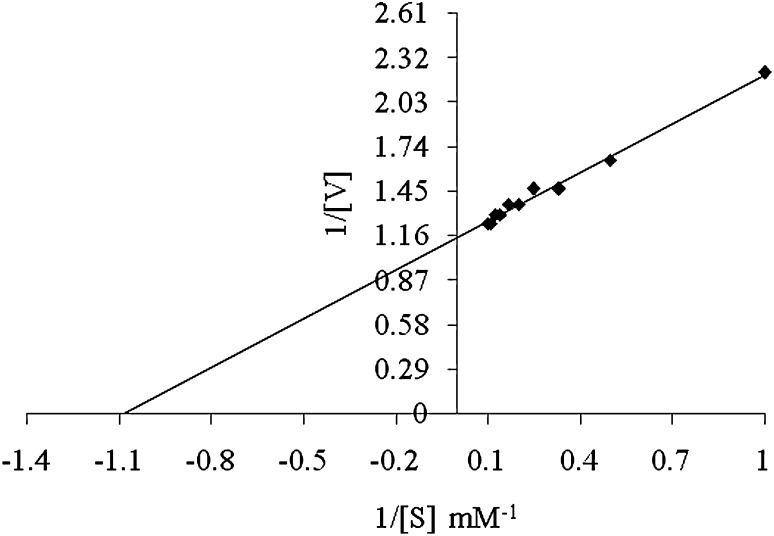

Kinetic Parameters of Nitrile-Hydrolysing Activity

The kinetic parameters of nitrile-hydrolysing activity were estimated over a range of acrylonitrile concentration (1–10 mM) at 30 °C in potassium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0).The apparent Km and Vmax values calculated for acrylonitrile were found to be 0.909 mM and 0.862 μmol min−1mg−1respectively as calculated from Lineweaver–Burk plot (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Lineweaver-Burk plot for nitrile-hydrolysing activity

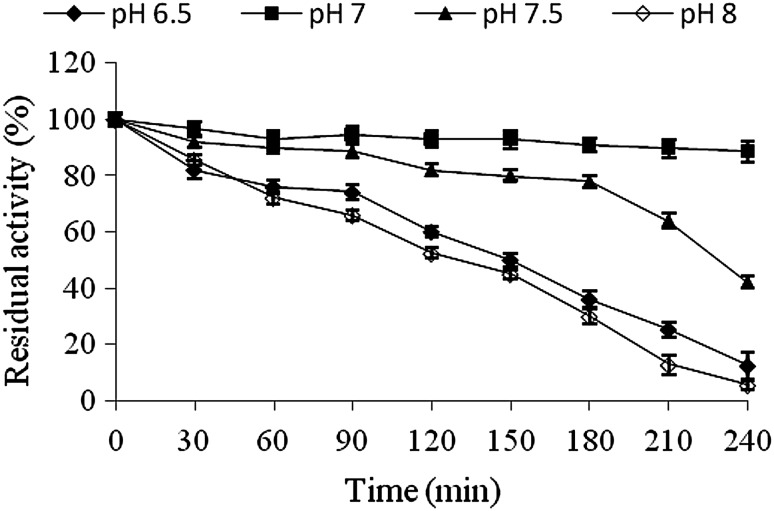

Thermostability and pH stability of the nitrile-hydrolysing activity

High thermal and pH stability of a biocatalyst is always a desired trait. Nitrile-hydrolysing activity was stable as it retained around 86 % and 80 % activity after 4 h (Fig. 4) and 8 h (data not shown) at 30 °C respectively, but was thermolabile with a half life of 120 min and 45 min at 40 °C and 50 °C respectively. Nitrile-hydrolysing activity showed higher stability at pH 7.0 (Fig. 5). The stability decreased as the pH was varied, both above and below pH 7.0.

Fig. 4.

Thermostability of nitrile-hydrolysing activity of I. variabilis RGT01

Fig. 5.

pH stability of nitrile-hydrolysing activity of I. variabilis RGT01

Involvement of Possible Nitrile-Hydrolysing Route

HPLC analysis of the reaction product(s) showed that acrylonitrile was converted to only one product i.e. acrylic acid (Fig. 6). No detection of acrylamide indicated no nitrile-hydratase activity in the cells. To confirm that acrylamide was not removed by the action of an amidase, the cells were examined for this activity with acetamide and acrylamide as substrates. These amides were not hydrolyzed by the resting cells (data not shown). Thus, indicating absence of amidase production under the experimental conditions used. Therefore, acrylamide, if formed by nitrile-hydratase, would mostly remain un-reacted in the reaction mixtures. This suggested that hydrolysis of acrylonitrile by I. variabilis RGT01 was catalyzed by the nitrilase in the present study.

Fig. 6.

HPLC analysis. a 0.5 mM acrylamide (RT-3.0), b 1 mM acrylic acid (RT-3.9), c biotransformed product (RT-3.9) from the reaction mixture. RT: retention time

Conclusions

We have successfully isolated a novel nitrile-hydrolysing strain, I. variabilis RGT01. The substrate range of the microbe included aliphatic, aromatic and arylaceto-nitriles. The microorganism produced nitrile-hydrolysing enzyme in MSM supplemented with a cheaper inducer acetonitrile. Thus, reducing overall enzyme production cost. It was able to biotransform acrylonitrile to acrylic acid. It could be utilized as a biocatalyst for the hydrolysis of low molecular weight nitriles.

Acknowledgments

Gurdeep Kaur gratefully acknowledges Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Govt. of India, for the fellowship. Dr. Rakesh Sharma, IGIB, New Delhi for identification of the strain.

References

- 1.He Y-C, Xu J-H, Su J-H, Zhou L. Bioproduction of glycolic acid from glycolonitrile with a new bacterial isolate of Alcaligenes sp. ECU0401. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2010;160:1428–1440. doi: 10.1007/s12010-009-8607-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng Y-G, Chen J, Liu Z-Q, Wu M-H, Xing L-Y, Shen Y-C. Isolation, identification and characterization of Bacillus subtilis ZJB-063, a versatile nitrile-converting bacterium. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;77:985–993. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1236-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang H, Sun H, Wei D (2013) Discovery and characterization of a highly efficient enantioselective mandelonitrile hydrolase from Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315 by phylogeny-based enzymatic substrate specificity prediction. BMC Biotechnol 13:14. doi:10.1186/1472-6750-13-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Zhang C-S, Zhang Z-J, Li C-X, Yu H-L, Zheng G-W, Xu J-H. Efficient production of (R)-o-chloromandelic acid by deracemization of o-chloromandelonitrile with a new nitrilase mined from Labrenzia aggregata. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;95(1):91–99. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-3993-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee A, Kaul P, Banerjee UC. Enhancing the catalytic potential of nitrilase from Pseudomonasputida for stereoselective nitrile hydrolysis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;72:77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueller P, Egorova K, Vorgias CE, Boutou E, Trauthwein H, Verseck S, Antranikian G. Cloning, overexpression, and characterization of a thermoactive nitrilase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus abyssi. Prot Exp Purif. 2006;47:672–681. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamal A, Kumar MS, Kumar CG, Shaik TB. Bioconversion of acrylonitrile to acrylic acid by Rhodococcus ruber strain AKSH-84. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;21:37–42. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1006.06044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banerjee A, Sharma R, Banerjee UC. The nitrile-degrading enzymes: current status and future prospects. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;60:33–44. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gong J-S, Lu Z-M, Li H, Shi J-S, Zhou Z-M, Xu Z-H. Nitrilases in nitrile biocatalysis: recent progress and forthcoming research. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:142–185. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen M, Zheng Y-G, Shen Y-C. Isolation and characterization of a novel Arthrobacter nitroguajacolicus ZJUTB06-99, capable of converting acrylonitrile to acrylic acid. Process Biochem. 2009;44:781–785. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2009.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holt JG, Kreig NR, Sneath PHA, Staley JT, Williams ST. Bergey’s manual of determinative bacteriology. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fawcett JK, Scott JE. A rapid and precise method for the determination of urea. J Clin Pathol. 1960;13:156–159. doi: 10.1136/jcp.13.2.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakalidou A, Kampfer P, Berchtold M, Kuhnigk T, Wenzel M, Konig H. Cellulosimicrobium variabile sp. nov., a cellulolytic bacterium from the hindgut of the termite Mastotermes darwiniensis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;52:1185–1192. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.01904-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Y, Li W-J, Tian W, Zhang L-P, Xu L, Shen Q-R, Shen B. Isoptericola jiangsuensis sp. nov., a chitin-degrading bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:904–908. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.012864-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Komeda H, Hori Y, Kobayashi M, Shimizu S. Transcriptional regulation of the Rhodococcus rhodochrous J1 nitA gene encoding a nitrilase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10572–10577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prasad S, Misra A, Jangir VP, Awasthi A, Raj J, Bhalla TC. A propionitrile-induced nitrilase of Rhodococcus sp. NDB 1165 and its application in nicotinic acid synthesis. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;23:345–353. doi: 10.1007/s11274-006-9230-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nageshwar YVD, Sheelu G, Shambhu RR, Muluka H, Mehdi N, Malik MS, Kamal A. Optimization of nitrilase production from Alcaligenes faecalis MTCC 10757 (IICT-A3): effect of inducers on substrate specificity. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2011;34:515–523. doi: 10.1007/s00449-010-0500-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandyopadhyay AK, Nagasawa T, Asano Y, Fujishiro K, Tani Y, Yamada H. Purification and characterization of benzonitrilases from Arthrobacter sp. strain J-1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;51:302–306. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.2.302-306.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu D, Mukherjee C, Biehl ER, Hua L. Discovery of a mandelonitrile hydrolase from Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110 by rational genome mining. J Biotechnol. 2007;129:645–650. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu D, Mukherjee C, Yang Y, Rios BE, Gallagher DT, Smith NN, Biehl ER, Hua L. A new nitrilase from Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110 gene cloning, biochemical characterization and substrate specificity. J Biotechnol. 2008;133:327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang C, Wang X, Wei D. A new nitrilase-producing strain named Rhodobacter sphaeroides LHS-305: biocatalytic characterization and substrate specificity. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2011;165:1556–1567. doi: 10.1007/s12010-011-9375-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagasawa T, Nakamura T, Yamada H. ε-Caprolactam, a new powerful inducer for the formation of Rhodococcus rhodochrous J1 nitrilase. Arch Microbiol. 1990;155:13–17. doi: 10.1007/BF00291267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cramp R, Martin Gilmour M, Cowan DA. Novel thermophilic bacteria producing nitrile-degrading enzymes. Microbiology. 1997;143:2313–2320. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-7-2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]