Abstract

Patient: Male, 31

Final Diagnosis: Myositis ossificans

Symptoms: Back pain • motion restriction • tenderness in lumbar region

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Neurology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Myositis ossificans is a non-neoplastic benign reactive bone and cartilage matrix-producing pseudotumor that develops in skeletal muscles adjacent to the joint. The clinical and pathologic appearance of myositis ossificans varies depending on the time elapsed after heterotopic bone formation. Although its etiology is unclear, it usually occurs at the site of the injured muscle, most commonly in large muscles of the extremities, especially the quadriceps and brachialis. It rarely occurs in the paravertebral muscle of the lumbar spine.

Case Report:

We present the rare case of a 31-year-old Turkish man with calcifying myositis ossificans not associated with trauma, referred to our hospital with severe low back pain with restriction of low back motions. Radiological investigation suggested a sclerotic osteoblastic on the left facet joint of L4–5. To confirm the diagnosis, the patient was managed surgically by total excision of the mass, which resulted in a good functional recovery. At his 12-month follow-up examination, he was neurologically intact and no recurrence was seen.

Conclusions:

Cases like this should be investigated well, so careful correlation of the clinical and radiologic findings with taking a biopsy is necessary to confirm diagnosis.

MeSH Keywords: Lumbar Vertebrae, Myositis Ossificans, Paraspinal Muscles

Background

Myositis ossificans (MO) is a non-neoplastic benign condition that appears as a heterotopic, well-defined bone formation in muscles and soft tissues [1]. The etiology is unknown, and major injury (dislocations, fractures) or minor trauma is considered as the most frequent cause [1]. The most common sites affected are the hip, anterior thigh (quadriceps), anterior arm (brachialis), and in the soft tissues adjacent to the elbow joint [2,3]. MO typically occurs in young and athletic adults [3]. Males and females are affected equally [3]. Patients present with a short history (usually less than 3 months) of pain and swelling in the affected area. These lesions can limit joint motion and progress to ankylosis in a small proportion of patients [3]. In radiological investigations, it is difficult to distinguish this condition from soft tissue and bone malignancy; therefore, careful correlation of the clinical and radiologic findings with taking a biopsy is necessary to confirm diagnosis [3,4]. This case report describes a rare case of calcifying myositis ossificans in paravertebral muscles in the lumbar spine, not associated without cortical involvement, and suspected of being malignant soft tissues. The 31-year-old male patient was referred to our hospital with severe low back pain with restriction of low back motions. There was no relevant history of trauma or family history of interest. Total excision of the mass resulted in a good functional recovery.

Case Report

This 31-year-old Turkish male patient was referred to our hospital with complaints of severe low back pain that had been restricting his motions for more than 5 months. There was neither trauma, including exercise-related trauma nor family history, of interest in his past medical history. He had been unsuccessfully treated with medical treatment and physical therapy for 3 months. On physical examination, a severe tenderness in the left lumbar region at the area extended between both L3 and L5 vertebrae by palpation. There was no erythema. The laboratory findings were normal. Neurological examination revealed no motor or sensory deficits, with normal reflexes. Muscular strength and tonus were normal. Both Hoffman and clonus reflexes were bilaterally negative. Before the patient was referred to our hospital, he went to another medical centre, where he underwent radiography CT, and MR imaging, showing a regular ossified mass in the paravertebral muscle on the left facet joint of L4–5. MR imaging of the lumbar spine revealed an inhomogeneous, well-formed shell of a bony lesion, sized approximately 20×20 mm, on the left facet joint of L4–5; it was a hyperintense lesion on T2-weighted images, compatible with a sclerotic, osteoblastic lesion such as osteoma, osteochondroma, or synovial cyst (Figure 1). There was no evidence of disc space narrowing or disc signal to suggest that the entity was a calcified disc herniation. There was no spinal cord signal abnormality.

Figure 1.

Axial image on T2-weighted MR shows (*): a hyperintense area; inhomogeneous, well-formed shell bony mass above left facet joint of L4–5, compatible with a sclerotic lesion.

Because of the persistent local tenderness, intractable local pain, and restriction of motions, the patient was operated on with the primary diagnosis of an expansile sclerotic-osteoblastic lesion on the left facet joint of L4–5 to confirm the diagnosis. Surgery was conducted under general anesthesia. The patient was placed prone, and a midline vertical incision that extended between the levels of spinous processes of L4 to L5 vertebrae was made. Above the left facet joint of L4–5, a well-circumscribed, gray-yellow colored and bony solid mass with gritty areas (Figure 2) was seen. The mass was totally excised. The patient had no neurological deficits after surgical treatment. Unfortunately, the patient’s low back pain had not completely disappeared after the surgery. The patient’s preoperative Visual Analogue Score (VAS) was 10 and severe low back pain occurred when moving. Postoperative VAS was 5 on the second postoperative day; his pain was acceptable and he responded to oral analgesic medications. After 2 days of hospitalization, the patient was neurologically intact and discharged without any problems. The patient returned home in good condition. The histological and pathological examinations of the surgical specimen confirmed the diagnosis of myositis ossificans (Figure 3A, 3B).

Figure 2.

Well-circumscribed, gray-yellow colored and bony solid mass with gritty areas that was surgically excised from the patient.

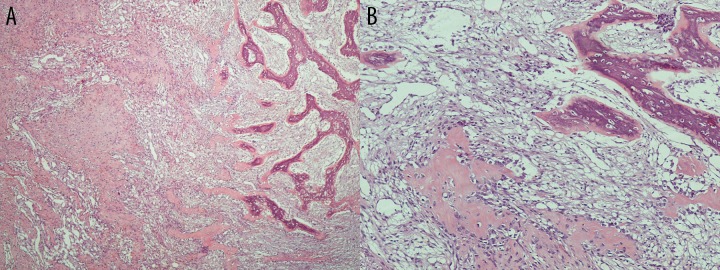

Figure 3.

(A, B) On the left side are seen light pink stained areas of immature osteoid and on the right side are seen purple stained areas of mature bone formation (magnification ×200, hematoxylin and eosin staining).

At his 12-month follow-up examination, the patient has no neurological deficits, he attained substantial improvement in low back motions as a result of bone excision, VAS was 2, and physical examination revealed a postoperative surgery scar without other pathological changes.

Discussion

Myositis ossificans (MO), so-called “heterotopic ossification”, is a benign condition that appears as a heterotopic, well-defined bone formation in muscles and soft tissues [1]. This condition is rare; annual incidence is less than 1 per 1 million individuals. Both sexes are affected equally [3]. It is usually confined to a single muscle or muscle group, and is most common in young (mean age, 23.8 years), athletic men within the second and third decade of life [3,5,6]. Over 75% of cases of MO occur in the large skeletal muscles of proximal extremities (the quadriceps and brachialis muscles are the most common sites) [2,3,5–7], and location in the lumbar spine is rare. The pathogenesis of MO remains unclear, although trauma is the most common cause.

MO is classified into 3 types [2,8–10]: 1) Myositis ossificans progressiva: This is a metabolic disorder occurring in children, with widespread metamorphosis of muscle into bone, and all of the skeletal muscles progressively becoming involved. It is a rare, inherited disorder, characterized by fibrosing and ossification of muscles, tendons, and ligaments of multiple sites. 2) Traumatic myositis ossificans circumscripta: This follows a local acute or chronic trauma and occurs in 60–75% of all cases. 3) Myositis ossificans circumscripta without history of trauma (non-traumatic MOC): This is usually found in paraplegia, chronic infections, burns, and poliomyelitis. The etiology is unknown. Major injury (dislocations, fractures) and minor trauma are considered the most frequent causes [1]. In a small number of cases, possible etiologies include infections, burns, neuro-muscular disorders, hemophilia (factor-IX deficiency), tetanus, and drug abuse [4]. In our case, there was neither trauma nor family history of interest.

Patients present with a short history (usually less than 3 months) of pain and swelling in the affected area; occasionally there may be localized erythema in the overlying skin [3]. A correct diagnostic of MO must be 3-dimensional, based on clinical examination, radio-imaging and histological examination, while the laboratory test results are usually normal [10].

Risk factors include male sex, past history of having formed heterotopic bone, hypertrophic osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis [3]. MO is essentially a proliferative mesenchymal response to an initiating injury to the soft tissue (not necessarily to the muscle), which leads to localized ossification. In the first week, richly vascularized, proliferative fibroblastic cells are prominent. These primitive mesenchymal cells, with high mitotic activity, can mimic malignancy on biopsy. With maturation of the lesion, which is variable, a typical zonal pattern develops, with 3 distinct zones: 1) the center consists of rapidly proliferating fibroblasts with areas of hemorrhage and necrotic muscles; 2) the intermediate or middle zone is characterized by osteoblasts with immature osteoid formation and islands of cartilage due to enchondral ossification; 3) the peripheral zone is composed of mature bone, usually well separated from the surrounding tissue by myxoid fibrous tissue. Ackerman named it as the “zone phenomena” and it is an important criterion for the diagnosis of MO [10,11]. By the third to fourth week calcifications and ossifications appear inside the mass, and by the sixth to eighth week well-organized cortical bone with cortex and marrow space formation develops at the periphery [4,9–13]. These histopathological changes explain mistaken diagnoses as an osteosarcoma or other soft tissue tumors; therefore, in suspected cases we have to leave surgical treatment as the last option to avoid misdiagnosis. In our case, the patient experienced severe low back pain for 5 months and waited for 3 months while he was unsuccessfully treated with medical treatment and physical therapy. This condition helped arrive at the correct diagnosis, confirmed histopathologically.

Computed tomography is the criterion standard in characterizing typical findings of myositis ossificans such as extensive muscle and perilesional edema without bone marrow or cortical abnormalities. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings vary depending on the stage of maturation and the histologic pattern of the lesion. For early-stage lesions, T2-weighted images show a heterogeneous localized mass with high signal intensity in the central area. As the lesion matures, the peripheral ossification becomes denser, and the T2-weighted MRI shows a hyperintense area with surrounding hypointense rim as a well-defined, inhomogeneous soft tissue mass, surrounded by a frame of lower signal intensity, signifying cortical calcification [14], as we found in our case. On T1-weighted images, the lesion is isointense to the muscle and can be identified by mass effect, but it may demonstrate rim enhancement in the acute phase after contrast administration [14].

The differential diagnosis considered after surgical excision is done includes osteochondroma, osteoma, or synovial cyst, the as same as in MO. The most frequent clinical misdiagnosis is tumors, especially osteosarcoma [1]. In our patient, the radio imaging (MRI) made us think about the possibility of osteochondroma, osteoma, or synovial cyst. Diagnostic problems in such cases occur when the lesion is biopsied in the early phase before peripheral maturation has occurred [9]. The MO lesion is usually 2–5 cm in diameter and is adherent to the surrounding muscle, as we found in our patient. It may be difficult on the basis of histological evidence alone to differentiate a focus of MO from a sarcoma. Therefore, careful correlation of the clinical and radiologic findings is essential [9].

MO is a benign, self-limited process with an excellent prognosis. Treatment in most cases is conservative; it consists of rest, ice, and anti-inflammatory drugs to relieve pain. Physiotherapy can also help improve movements by performing passive and active motion [3,5,10,12]. Typically, a regression of the symptoms is seen in the course of disease (30%) [10]. A spontaneous resorption or an incomplete regression can occur [10]. Surgical intervention is recommended when the heterotopic bone has matured. The optimum time for surgical excision is 9–12 month after the heterotopic formation [10]. However, surgical excision is advised when joint function is impaired, neurovascular impingement is encountered, or the lesion is unusually large or painful [15]. Recurrence is extremely uncommon, even when resection margins are positive [3].

Conclusions

This case is was an unusual localization for a MO. There was neither trauma nor family history of interest. Surgery excision was performed earlier because of the persistent local modifications, the intractable local pain, and the limitation of function. MR images compatible with a sclerotic, osteoblastic lesion (e.g., osteoma, osteochondroma, or synovial cyst) suggest a possible MO, but in such cases careful correlation of the clinical and radiologic findings with a biopsy is necessary to confirm diagnosis.

Footnotes

Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References:

- 1.Micheli A, Trapani S, Brizzi I, et al. Myositis ossificans circumscripta: a pediatric case and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168(5):523–29. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0906-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel S, Richards A, Trehan R, et al. Post-traumatic myositis ossificans of the sternocleidomastoid following fracture of the clavicle: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:413. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-1-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folpe AL, Inwards CY. Osteocartilaginous tumors. In: O’Connell JX, editor. Bone and soft tissue pathology (a volume in the series foundations in diagnostic pathology) Philadelphia: Saunders-Elsevier; 2010. pp. 239–54. series editor: Goldblum JR. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jose AF, Mercedes CM, Salvador AS, et al. Myositis ossificans circumscripta without history of trauma. J Clin Med Res. 2010;2(3):142–44. doi: 10.4021/jocmr2010.05.364w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.John AO. Complications. In: Ogden JA, editor. Skeletal injury in the child. 3rd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000. pp. 311–45. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarthy EF, Sundaram M. Heterotopic ossification: a review. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34(10):609–19. doi: 10.1007/s00256-005-0958-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kokkosis A, Balsam D, Lee TK, et al. Pediatric nontraumatic myositis ossificans of the neck. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(4):409–12. doi: 10.1007/s00247-009-1165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paterson DC. Myositis ossificans circumscripta, report of four cases without history of injury. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1970;52:296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peter GB. Bengin soft tissue tumors. In: Peter GB, editor. Orthopaedic Pathology. 5th ed. Missouri: Mosby Elsevier; 2010. pp. 497–532. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Man SC, Schnell CN, Fufezan O, Mihut G. Myositis ossificans traumatica of the neck – a pediatric case. Maedica (Buchar) 2011;6(2):128–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ackermann LV. Extra-osseous localized non neoplastic bone and cartilage formation (so called myositis ossificans) J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1958;40(2):279–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gattuso P, Reddy VB, David O, et al. Soft tissue. In: Robin DL, Mark RW, editors. Differential diagnosis in surgical pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders – Elsevier; 2010. pp. 888–948. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carreiro JE. Femur, hip and pelvis. In: Carreiro JE, editor. Pediatric manual medicine, an osteopathic approach. Printed in China: Elsevier; 2009. pp. 193–272. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parikh J, Hyare H, Saifuddin A. The imaging features of posttraumatic myositis ossificans, with emphasis on MRI. Clin Radiol. 2002;57(2):1058–66. doi: 10.1053/crad.2002.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishio J, Nabeshima K, Iwasaki H, Naito M. Non-traumatic myositis ossificans mimicking a malignant neoplasm in an 83-year-old woman: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:270. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]