Abstract

Soybean protein was taken as a model protein to investigate two aspects of the protein extraction by sodium bis(2-ethylhexyl) sulfosuccinate (AOT) reverse micelles: (1) the forward protein extraction from the solid state, and the effect of pH, AOT concentration, alcohol and water content (W0) on the transfer efficiency; (2) the back-transfer, the capability of the protein to be recovered from the micellar solution. The experimental results led to the conclusion that the highest forward extraction efficiency of soybean protein was reached at AOT concentration 180 mmol l−1, aqueous pH 7.0, KCl concentration 0.05 mol l−1, 0.5 % (v/v) alcohol, W0 18. Under these conditions, the forward extraction efficiency of soybean protein achieved 70.1 %. It was noted that the percentage of protein back extraction depended on the salt concentration and pH value. Around 92 % of protein recovery was obtained after back extraction.

Keywords: Reverse micelles, Forward extraction, Backward extraction, Soybean protein

Introduction

Soybean has been an important protein-oil crop in many countries, and has widely applied in food industries (Chinma et al., 2011; Gandhi et al., 2001). Soybean seed contains approximately 17 % oil and 40 % protein. Traditionally, the separation of soybean protein has been done by alkaline extraction and isoelectric precipitation (Wagner et al., 1996). This procedure is based on being prepared after extraction of the soybean oil. However, this method has some fatal defects: a great deal of wastewater is produced which causes serious environmental pollution and it is also limited capacity of raw material treatment and high consumption of acid and alkali. Moreover, it is easy to cause physicochemical changes of proteins (Ohren, 1981). Therefore, it was felt necessary to explore an alternative extraction approach of soybean protein.

Reverse micelles are mimetic systems of biological membranes composed of amphiphilic molecules that self-organize with hydrocarbon chains facing the organic solvent and polar head-groups pointing inwards (Luisi et al., 1988). Some researchers have been reported the advantages of reverse micelle extraction protein, such as no loss of native function/activity, low interfacial tension, ease of scale up, potential for continuous operation and modifing the structure and function of protein (Krishna et al., 2002; Nishiki et al., 2000; Zhao et al., 2008a; Zhao et al., 2008b)). And the oil and protein from vegetable meals were simultaneously extracted AOT reverse micelles (Leser and Luisi, 1989). The steps of extraction included the forward and backward extraction. The forward-extraction could solubilize protein into the reverse micellar solution from vegetables, while the backward-extraction could recover the solubilized protein from the reverse micellar solution (Leser et al., 1993).

In reverse micelles, the hydrophobic effects, hydrogen bonding interaction, electrostatic interaction, steric hindrance interaction of micelles and proteins may affect the extraction efficiency of protein (Correa et al., 1998). Besides other factors, i. e. pH and ionic strength in reverse micelles (Matzke et al., 1992), may also affect the extraction of proteins. In addition, the alcohol molecule was used to control the formation and destruction of the reverse micelles, and improve the backward extraction efficiency of protein (Hong and Kuboi, 1999). Very limited information is available to investigate the effect of alcohol addition on the forward extraction efficiency of soybean protein in reverse micelles.

This article was aimed at discussing two aspects: the solid state extraction of soybean protein and the so-called “back transfer”: when the soybean protein was separated from other components by reverse micelles, it must be eventually recovered into a water solution.

Materials and methods

Materials

Sodium bis(2-ethylhexyl) sulfosuccinate (AOT) was purchased from sigma chemical Company (>98 %). Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) protein assay kit was purchased from USA Pierce Company. All other reagents were of analytical grade. Soybean (type No.8) was from market, Beijing. The soy flour was sieved through a 100 screen, Flour composition was as follows: total protein 37.53 % (by Kjeldhal, N × 6.25); fat 20.75 %; moisture 7.99 % and ash 6.5 % (2000). All values were given in wt.% of the total flour weight (AOAC, 2000).

Methods

Preparation of AOT reverse micelles

AOT reverse micelles were used to isolate protein from soy flour (Vassiliki et al., 1993). Stock solution of varying amounts of AOT (90, 135, 180, 225, 270, 315 mmol l−1) was obtained first by solubilizing AOT in hexane. When AOT dissolved completely, a KCl solution was added with varying concentrations (0.00, 0.05, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20, 0.25, 0.30, 0.35 mol l−1), pH (5.5, 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, 7.5, 8.0, 8.5, 9.0) and alcohol amounts (0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8 vol.%). The water content in reverse micelles was determined periodically with Karl-Fischer reagent in the monophasic area of the phase diagram. The total volume of water was usually expressed by the ratio W0 = [H2O]/[AOT]. By fixing AOT concentration and adding different amounts of KCl solution and alcohol, W0 was adjusted (W0 = 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21).

Forward extraction of soybean protein

The forward extraction experiments were carried out using an aqueous phase containing 0.25 g. ml−1 of soybean flour in a 50 ml stoppered conical flask. 30 ml of the organic phase (AOT/hexane) was added with an already well determined water content (W0 4–21), which consisted of a fixed KCl concentration and pH value, were mixed and shaken at 250 rpm for 30 min in a water bath at 40 °C. Phase separation was aided by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min to reach a clear separation of two phases. The upper organic phase was gathered for following back extraction. The protein content was measured with BCA method (microplate procedure, microplate reader 550:Japan Bio-RAD Company) (Smith et al., 1985). In order to prevent the interference of other species during measurements, the sample analyses were performed against appropriate blank solutions, which were prepared simultaneously with the protein sample. The forward extraction yield was calculated. Efficiency of forward extraction of soybean protein was expressed as (Umesh Hebbar et al., 2008):

|

1 |

Back extraction of soybean protein

The reverse micellar phase loaded with soybean protein from the forward extraction was added to an equivalent volume of aqueous phase, which contained a fixed AOT concentration, KCl concentration and pH value as well as 0.1–0.8 % (v/v) alcohol to conduct backward extraction process. The back transfer was finished in an orbital shaker at a speed of 250 rpm for 60 min at 35 °C. The mixture was centrifuged for 15 min at 4000 rpm to reach a clear separation of two phases. The soybean protein content was measured with the same method as in the forward extraction studies. The efficiency of soybean protein backward extraction was calculated as follows (Umesh Hebbar et al., 2008):

|

2 |

Statistical analysis

The data reported in text were an average of triplicate observation Efficiencies of soybean protein extraction were expressed as means ± SD. Statistical analysis of the data was done using the SAS software (Version 8.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA, 2001).

Results and discussion

Forward extraction

Effect of aqueous phase pH

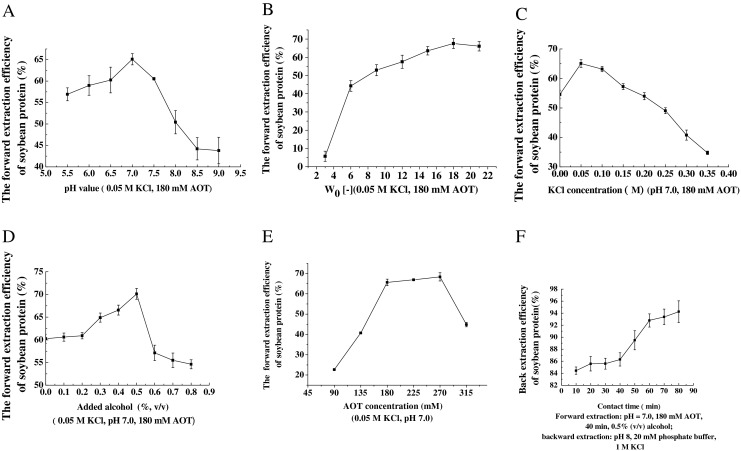

The effect of aqueous pH on soybean protein solubilization into the reverse micellar phase is shown in Fig. 1a. As the pH of aqueous phase increased from 8.5 to 9.0, the forward extraction efficiency of soybean protein decreased significantly. Maximum protein efficiency (65.1 %) was found at pH = 8.0, which was above the isoelectric point of soybean protein (4.5). It was interesting that the soybean protein was negatively charged and was not attracted by the AOT head-groups. In general, proteins were only transferred to the reverse micelles which their net charge was opposite to that of surfactant head-groups because solubilization was usually steered by electrostatic interactions between protein molecule and the surfactant headgroup (Mathew and Juang, 2005). Extraction of soybean protein at pH higher than the pI indicated that the driving force responsible for extraction in the present case could be the hydrophobic interaction or steric hindrance interaction of micelles and proteins (Ronnie et al., 1989). It was evident from Fig. 1, where at pH 9.0, the solubilization gradually decreased to 43.8 %, the reasons was that the proteins became positively charged at this pH, which resulted in poor hydrophobic or steric hindrance interaction from the negatively charged surfactant head-groups.

Fig. 1.

Effect of a Aqueous pH, b W0, c KCl concentration, d Added alcohol, e Sodium bis(2-ethylhexyl) sulfosuccinate (AOT) concentration on the forward extraction and f Contact time during backward extraction of soybean protein (Means ± standard deviations n = 3)

Effect of water content (W0)

Water content of reverse micellar phases is a critical parameter in extraction and concentration of protein. The forward extraction efficiency was extremely low (5.7 %) at W0 3, without altering the surfactant concentration. As observed in Fig. 1b, with W0 from 9 to 21, the forward extraction efficiency increased to 34.3 and 67.5 %, respectively. The change of W0 due to change in organic phase volume could be the reason for observed variation in extraction efficiency. When W0 reached 18, the forward extraction efficiency levelled off. The increase of W0 corresponded to the increase of micelle size and the protein solubilization was strongly dependent on micelle size. The size of micelle relative to the size of a protein was critical to the ability of the micelle to solubilize the protein (Göklen and Hatton, 1987). The addition of protein to reverse micelles did not appreciably solubilize the protein until the diameter of the reverse micelle was similar to that of the protein (Matzke et al., 1992). With increasing of W0, the number and size of the reverse micelles would increase, favoring higher solute extraction (Ichikawa et al., 1992). This result was consistent with the report of Leser and Luisi (1989).

Effect of ionic strength

Forward extraction was carried out at pH 7.0 using an aqueous phase consisting of different KCl concentrations. The ionic strength effect on soybean protein solubilized into the reverse micelles is shown in Fig. 1c. With the increasing of the KCl concentration from 0.05 to 0.35 mol l−1, the forward extraction efficiency considerably decreased (Fig. 1c). However, a minimum KCl concentration at 0.05 mol l−1 was needed for the protein extraction to take place, which agreed with the investigation of Harikrishna et al. (2002). The KCl concentration affected the transfer behaviour of protein due to micelle size changes or screening of electrostatic interactions between the protein and the micelle wall (Göklen and Hatton, 1987). An increase of KCl concentration led to a decrease of the interaction intensity through a screening effect. This electrostatic screening effect was responsible for decreasing the surfactant head-group repulsions, resulting in the formation of smaller reversed micelles for the system used here (Göklen and Hatton, 1987; Umesh Hebbar and Raghavarao, 2007). The expulsion of the solute from the core due to reduction in reverse micellar size with increasing salt concentration (squeezing out effect) and reduction in Debye length might have resulted in the lower extraction efficiency at higher salt concentrations (Krishna et al., 2002).

Effect of alcohol during forward extraction

The effect of ethanol on the forward extraction efficiency of soybean protein in reverse micelles was also investigated. The experiment result is shown in Fig. 1d. As the amount of ethanol increased initially, forward-extraction efficiency of soybean protein increased synchronously and a maximum extraction (70.1 %) was obtained when alcohol amount was 0.5 % (v/v). Apparently, the addition of alcohol promoted the forward-transfer of soybean protein. It was suggested that the addition of small amount of alcohol could affect the micellar–micellar interaction of the reverse micelles system. The hydrophobic hydrocarbon group suppressed the intermicellar attractive interaction proportionally to their chain (carbon) length, and the hydrophilic hydroxyl group enhanced the interaction (Hong and Kuboi, 1999). But the extraction efficiency decreased when the addition of alcohol was higher than 0.5 % (v/v). The reason might be attributed to very high addition of alcohol probably leading to the increase of the attractive interaction between reverse micelles and the arrangement of AOT molecules in hexane, which caused instability of reverse micelles and also the decreasing of solubilization of soybean protein in reverse micelles.

Effect of AOT concentration

The surfactant AOT concentration in the organic phase was varied (Fig. 1e) in the range of 90–315 mmol l−1, while maintaining the aqueous pH, KCl concentration, alcohol amount and W0 at 7.0, 0.05 mol l−1, 0.5 % (v/v) and 18, respectively. The results indicated that when AOT concentration varied from 90 to 315 mmol l−1, the forward-extraction efficiency rapidly increased. The extraction efficiency of soybean protein increased with the surfactant concentration and the maximum extraction efficiency (68.36 %) was obtained at 180 mmol l−1. After this point, the forward extraction efficiency started to decrease with the increase of the AOT concentration, at last levelling off. The forward extraction efficiency increased with an increasing of AOT concentration. This was in agreement with the investigation of Liu et al. (2004a, b). This result was due to that the amount of surfactant aggregation and/or the size of reverse micelles was affected by the AOT concentration (Cabral and Aires-Barros, 1993). It was observed that when the surfactant concentration was above 315 mmol l−1, the turbidity of the phases increased, making the separation of the phases difficult. The reason might be that the reverse micellar system had higher viscosity and lower surface tension at very high AOT concentration, which led to inter-micellar collision and hindrance to the diffusion of solute by surfactant aggregates, so more proteins could not solubilize in reverse micelles (Krishna et al., 2002).

Back extraction

Back extraction of soybean protein from the reverse micellar phase of forward extraction was carried out by contacting it with the fresh aqueous phase (buffer with salt) (Mathew and Juang, 2005). The organic phase obtained from the forward extraction, which had given maximum extraction (AOT: 180 mmol l−1, KCl: 1 mol l−1, and aqueous pH 8.0) was used for back extraction. During back extraction, the effect on backward extraction of protein on back efficiency was studied by the varied salt concentration, aqueous phase pH, contact time and temperature.

Effect of ionic strength

It was reported that addition of higher amount of salt during back extraction destabilizes the reverse micelles and transfers the solute into the fresh aqueous phase (Mathew and Juang, 2005). Table 1 shows the effect of salt concentration in the stripping aqueous phase on protein recovery. As the concentration of KCl increased, the soybean protein recovery kept about constant when the KCl concentration was lower than 0.8 mol l−1 (aqueous pH 8.0), but increased significantly when the KCl concentration was higher than 0.8 mol l−1. The drastic increase in back extraction efficiency with change in salt concentration indicated the sensitivity of the system for ionic strength. Further improvement in the extraction was not observed with increasing KCl concentration. It could be stated that a strong interaction between the solubilized protein and micelles induced the micelle–micelle interaction or micellar cluster formation, resulting in a decrease of back-extracted fractions (Mathew and Juang, 2005). Hence, the control of micelle–micelle interaction may become a very important factor for the success of back extraction of the proteins.

Table 1.

Effect of processing conditions on back extraction efficiency of soybean protein in AOT/hexane reverse micellar system (Means ± standard deviations n = 3)

| Process parameter | Value | Back extraction efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Salt concentration (M)a | 0.6 | 85.7 ± 2.9 |

| 0.8 | 91.0 ± 1.4 | |

| 1 | 95.2 ± 1.8 | |

| 1.2 | 94.5 ± 1.2 | |

| Aqueous phase pHb | 6 | 69.5 ± 1.6 |

| 7 | 76.6 ± 1.1 | |

| 8 | 90.0 ± 1.8 | |

| 9 | 82.3 ± 1.1 |

AOT: Sodium bis(2-ethylhexyl) sulfosuccinate

Forward extraction conditions: Soybean flour, 0.25 g ml−1; pH 7.0; KCl, 0.05 M; AOT, 180 mM

apH 8.0, volume ratio: 1:1

bKCl concentration 1 M

Effect of aqueous pH value

Back extraction of soybean protein was carried out using a fresh aqueous phase with 1 mol l−1 of KCl at different pH values, pH of the fresh aqueous phase used for the back extraction was altered (6.0 and 9.0). The Table 1 shows that the back extraction reaches maximum at pH above pI, i.e., 4.5. The maximum possible back extraction was 90 % at pH 8.0. In this work, the extracting aqueous phase 1 mol l−1 KCl and 20 mmol l−1 phosphate buffer pH 8.0 were used. The pH 8.0 was a good compromise between protein stability and lower tendency to forward transfer (Liu et al. 2004a, b). Higher aqueous pH value combined with increased salt concentration might have destroyed the cell of the reverse micelles resulting in higher back transfer efficiency.

Effect of contact time during backward extraction

Figure 1f shows the effect of contact time during backward extraction on soybean protein efficiency. Protein recovery increased quickly with the increase of contact time and reached a plateau at the time of 60 min. Maximal protein efficiency was reached when the stripping aqueous phase consisted of pH 8.0, 20 mmol l−1 phosphate buffer and 1 mol l−1 KCl. The plateau of backward-extraction efficiency indicated that the extraction equilibrium was reached at the contact time of 60 min. Therefore, the optimum extraction time should be 60 min.

Conclusions

AOT/hexane reverse micelles were chosen for separation of soybean protein. About 70.1 % of soybean protein was forward extracted from reverse micellar solution. Soybean protein could be transferred out of the reversed micellar systems with up to 92 % backward extraction efficiency.

Addition of alcohol to AOT/hexane reverse micellar systems increased the forward extraction efficiency as compared to AOT alone. The optimum pH of soybean flour for extraction was 7.5–8. Increasing AOT concentration led to the increase of protein recovery. The optimum AOT concentration was 180 mmol l−1. When the stripping aqueous phase consisted of pH 8.0, 20 mmol l−1 phosphate buffer, 1 mol l−1 KCl and 60 min, the equilibrium achieved in the backward was different to that in the forward extraction within same order of magnitude.

Acknowledgment

Financial support of this work by Promotive Research Fund for Excellent Young & Middle-aged Scientists of Shandong Province of China (Grant no. BS2010NY027) and Science & Technology Development Planning of Shandong Province of China (Grant no. 2011GGC02044).

Contributor Information

Xiaoyan Zhao, Phone: +86-531-83179825, FAX: +86-531-88960332, Email: zhaoxiaoy@yahoo.cn.

Qiang Ao, Phone: +86-531-83179825, FAX: +86-531-88960332, Email: aoqiang@tsinghua.edu.cn.

References

- AOAC (2000) Official methods of analysis, 17th Ed. Association of Official Analytical Chemists Arlington VA

- Cabral JMS, Aires-Barros MR. In: Recovery processes for biological materials. Kennedy JF, Cabral JMS, editors. UK: Wiley; 1993. pp. 247–271. [Google Scholar]

- Chinma CE, Ariahu CC, Abu JO (2011) Chemical composition, functional and pasting properties of cassava starch and soy protein concentrate blends. J Food Sci Technol. doi:10.1007/s13197-011-0451-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Correa NM, Durantini EN, Silber JJ. Binding of nitrodiphenylamines to reverse micelles of AOT in n-hexane and carbon tetrachloride: solvent and substituent effects. J Colloid Interf Sci. 1998;208:96–103. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1998.5842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi AP, Jha K, Khare SK. Application of HACCP system for the production of edible grade soymean. J Food Sci Technol. 2001;38:68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Göklen KE, Hatton TA. Liquid-liquid extraction of low molecular-weight proteins by selective solubilization in reversed micelles. Sep Sci Technol. 1987;22:831–841. doi: 10.1080/01496398708068984. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harikrishna S, Srinivas ND, Raghavarao KSMS, Karanth NG. Reverse micellar extraction for downstream processing of proteins/enzymes. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2002;75:119–183. doi: 10.1007/3-540-44604-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong DP, Kuboi R. Evaluation of the alcohol-mediated interaction between micelles using percolation processes of reverse micellar systems. Biochem Eng J. 1999;4:23–29. doi: 10.1016/S1369-703X(99)00027-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa S, Imai M, Shimizu MS. Solubilizing water involved in protein extraction using reversed micelles. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1992;39:20–26. doi: 10.1002/bit.260390105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna SH, Srinivas ND, Raghavarao KSMS, Karanth NG. Reverse micellar extraction for downstream processing of proteins/enzymes. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2002;75:119–183. doi: 10.1007/3-540-44604-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leser ME, Luisi PL. The use of reverse micelles for the simultaneous extraction of oil and proteins from vegetable meal. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1989;34:1140–1146. doi: 10.1002/bit.260340904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leser ME, Mrkoci K, Luisi PL. Reverse micelles in protein separation: the use of silica for the back-transfer process. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1993;41:489–492. doi: 10.1002/bit.260410413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JG, Xing JM, Shen R, Yang CL, Liu HZ. Reverse micelles extraction of nattokinase from fermentation broth. Biochem Eng J. 2004;21:273–278. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2004.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JG, Xing JM, Shen R, Yang CL, Liu HZ. Reverse micelles extraction of nattokinase from fermentation broth. Biochem Eng J. 2004;21:273–278. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2004.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luisi PL, Giomini M, Pileni MP, Robinson BH. Reverse micelles as hosts for proteins and small molecules. Biochim Biophy Acta. 1988;947:209–246. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(88)90025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew DS, Juang RS. Improved back extraction of papain from AOT reverse micelles using alcohols and a counter-ionic surfactant. Biochem Eng J. 2005;25:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2005.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matzke SF, Creagh AL, Haynes LC. Prausnitz JM and Blanch HW, mechanisms of protein solubilization in reverse micelles. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1992;40:91–102. doi: 10.1002/bit.260400114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiki T, Nakamura K, Kato D. Forward and backward extraction rates of amino acid in reversed micellar extraction. Biochem Eng J. 2000;4:189–195. doi: 10.1016/S1369-703X(99)00048-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohren JA. Process and product characteristics for soya concentrates and isolates. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1981;58:333–335. doi: 10.1007/BF02582371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ronnie BG, Wolbert RH, Gijsbert V, Nachtegaal H, Dekker M, Van't Riet K, Bijsterbosch BH. Protein transfer from an aqueous phase into reversed micelles the effect of protein size and charge distribution. Eur J Biochem. 1989;184:627–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK, Krohn RI, Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Gartener FH, Rovenzano MDP, Fujimoto EK, Goeke NM, Olson BJ, Klenk KC. Measurement of protein using bichinchoninic acid. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umesh Hebbar H, Raghavarao KSMS. Extraction of bovine serum albumin using nanoparticulate reverse micelles. Progress Biochem. 2007;42:1602–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2007.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umesh Hebbar H, Sumana B, Raghavarao KSMS. Use of reverse micellar systems for the extraction and purification of bromelain from pineapple wastes. Bioresource Technol. 2008;99:4896–4902. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassiliki P, Aristotelis X, Athanasios EE. Proteolytic activity in various water-in-oil microemulsionsf as related to the polarity of the reaction medium. Colloid Surfaces B. 1993;1:295–303. doi: 10.1016/0927-7765(93)80004-I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JR, Sorgentini DA, An MC. Thermal and electroproretic behavior, hydrophobicity, and some functional properties of acid-treated soy isolates. J Agric Food Chem. 1996;44:1881–1889. doi: 10.1021/jf950444s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XY, Chen FS, Chen JQ, Gai GS, Xue WT, Li LT. Effects of AOT reverse micelle on properties of soy globulins. Food Chem. 2008;111:599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.04.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XY, Chen FS, Xue WT, Lee LT. FTIR spectra studies on the secondary structures of 7S and 11S globulins from soybean proteins using AOT reverse micellar extraction. Food Hydrocoll. 2008;22:568–575. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2007.01.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]