Introduction

Parental substance use is a prevalent global issue that has negative consequences for children (Barnard & McKeganey, 2004; Scott, 2009). An estimated 12% of U.S. children from 2002-2007 lived with at least one parent who abused alcohol or drugs (SAMSHA, 2009). Estimates from a 1990 Canadian sample found that 17% of children had a parent who experienced a substance use problem (Walsh, 2003), and an estimated 30% of children in the United Kingdom in 2004 lived with a parent who was a binge drinker (Manning, Best, Faulkner, & Titherington, 2009). Parental substance use is particularly relevant to child welfare as children whose parents misuse or abuse substances are disproportionately the victims of neglect or abuse, which may lead to placement in a foster home (Christoffersen & Soothill, 2003; Cunningham & Finlay, 2013; De Bortoli, Coles, & Dolan, 2013; Dunn et al., 2002; Young, Boles, & Otero, 2007). Further, parental substance use has been linked to other poor outcomes including lower probability of reunifying with a caregiver (Courtney & Hook, 2012), higher probability of termination of parental rights (Harris-McKoy, Meyer, McWey, & Henderson, 2013), and higher probability of being re-reported to child protection services (Laslett, Room, Dietze, & Ferris, 2012).

As one strategy for addressing parental substance use for families involved with child welfare, most states have implemented family drug treatment courts (FDTCs) (American University School of Public Affairs, 2012). These courts first appeared in the United States and were structurally modeled after drug treatment courts, though many of the key components had to be reformulated to address the unique needs of participants and their children (Pach, 2008). Recently, based on the experience of the United States, family drug and alcohol courts have been adopted in the United Kingdom and are based on the U.S. model (Bambrough, Shaw, & Kershaw, 2013; Harwin et. al., 2011). In addition, a Churchill Fellow has recommended that Australia consider implementing such courts (Levine, 2011).

Family drug treatment courts aim to reduce maltreatment by treating the underlying substance use problem through the collaborative efforts of treatment professionals in child welfare, the courts, and substance abuse agencies (Bureau of Justice Assistance, 2004). In contrast to adult drug treatment courts, which obtain referrals from the criminal courts, FDTCs in the United States obtain referrals from a caregiver, a parent’s attorney, a Department of Social Services (DSS) social worker, an attorney, a guardian ad litem, or a family court judge (Worcel, Green, Furrer, Burrus, & Finigan, 2007). FDTC participation is voluntary, and a parent may refuse to enroll; a parent is eligible when s/he has a chemical dependency that was a contributing factor in the maltreatment substantiation or dependency and has a pending case before the dependency court (Worcel et al., 2007). Such courts provide intensive judicial monitoring, timely and integrated treatment and wraparound services, frequent drug testing, weekly or biweekly court hearings, and rewards and sanctions associated with treatment compliance (Chuang, Moore, Barrett, & Young, 2012). These similarities exist in programs in the United States and in the United Kingdom, however, programs in the United Kingdom have a few key differences. For instance, cases enter the program at a later stage, residential treatment facilities are used infrequently, and the use of Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous is not typically an integral part of the treatment plan (Levine, 2011).

Although a local program may add other eligibility requirements, all courts in our study in North Carolina follow the state eligibility requirements. These basic requirements are that the parent be under the jurisdiction of the district court for a pending abuse, neglect, or dependency case; be diagnosed as chemically dependent or borderline chemically dependent; and agree to participate in the treatment court program (N.C. Administrative Office of the Courts [NCAOC], 2014). In addition, a committee established legal best practices and standardized forms for FDTCs in North Carolina (NCAOC, 2014).

Because a parent or guardian must have a pending abuse, neglect, or dependency case, FDTCs use the retaining or regaining of child custody as an incentive for participants to enroll in and complete the program. Abuse, neglect, and dependency cases are before the court in order for a judge to decide whether the status or condition of the child warrants government involvement (Hatcher, Mason, & Rubin, 2011).

Evidence from prior studies suggests that children of adults who enroll in FDTCs spend less time in foster care and experience higher rates of reunification with parents than children of similar adults not enrolled in FDTCs (Bruns, Pullmann, Weathers, Wirschem, & Murphy, 2012; Chuang et al., 2012; Worcel, Furrer, Green, Burrus, & Finigan, 2008). One small pilot study found evidence of lower probability of termination of parental rights following parental FDTC involvement (Dakof et al., 2010). However, these findings mainly come from single court studies serving a single county (e.g., Ashford, 2004; Boles, Young, Moore, & DiPirro-Beard, 2007; Bruns et al., 2012; Chuang et al., 2012), and were based on relatively small samples (e.g., Dakof et al., 2010; Green, Furrer, Worcel, Burrus, & Finigan, 2007).

The current study examines two questions. First, how does parental participation in the FDTC program affect length of time in foster care? Second, does participation in an FDTC affect reunification rates for youth in foster care? Engaging in a treatment program in which multiple resources, not just drug treatment, are provided to a participating family should yield a positive benefit and remediate the initial reason for removal, e.g., substance use. Although these questions have been addressed in part in other research, this study uses data from all FDTCs in one state and does not rely on the selection bias inherent in using only a small sample of courts that agree to release their data for a study.

Literature

A literature on FDTC effectiveness has emerged but remains relatively sparse (see Table 1). Our literature review revealed only 9 studies that have examined the effectiveness of FDTCs at improving child welfare outcomes. One of the most studied questions in this literature is, “Does FDTC participation affect the amount of time children spend in foster care?” This question is salient because federal legislation through the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 (Public Law 105-89) requires that permanency hearings be held within 12 months of a child entering temporary custody. The rationale for this time period reflects concerns that developing children need to have a secure attachment. However, this time period is relatively short from the perspective of treating an underlying substance use disorder (Bureau of Justice Assistance, 2004). Results from existing studies about how time in foster care is affected by FDTC participation are mixed. Although the results of some studies have suggested shortened length of time (Bruns et al., 2012; Burrus, Mackin, & Finigan, 2011; Green, Furrer, et. al 2007; Worcel et al., 2008), other studies find the opposite (Chuang et al., 2012). One study (Green, Furrer, Worcel, Burrus, & Finigan, 2009) found that the effect of FDTC on time in care varied by site.

Table 1.

Studies of the Effects of Family Drug Treatment Courts on Child Welfare Outcomes

| Study | Sample/ comparison group | Foster care Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Ashford, 2004 |

Location: Pima County Arizona Treatment: 33 participants Control A: 42 treatment refusal Control B: 45 treatment as usual |

◆ No statistically significant differences between groups on the percent that had a child returned to a parent ◆ Permanency decision reached within 1 year: 79% of FDTC group vs. 75% of treatment refusal and 49% of treatment as usual ◆ Mean # of months until permanency decision was reached 8.4 months for FDTC vs. 7.7 months for treatment refusal and 11.4 months for treatment as usual ◆ Re-entry into care: 46% of children involved with FDTC parents reentered vs. 30% of treatment refusal and 50% of treatment as usual |

| Boles et. a. 2007 |

Location: Sacramento, CA Treatment: 573 parents and 861 children Control: 111 parents and 173 children from the same site |

◆ 42% FDTC children were reunified within 24 months vs. 27% of the comparison children ◆ FDTC children spent fewer days in out of home care than comparison children (981 vs. 993) ◆ No differences in probability of re- entering foster care |

| Green, Furrer, et. al 2007 |

Location: 4 sites—2 in California, 1 in Nevada and 1 in NY Treatment: 250 FDTC participants including 50 high intensity treatment service cases Control: 200 similar parents who did not receive FDTC services in each site. |

◆ A higher proportion of FDTC parents were reunified with at least 1child (57% vs. 44%) ◆ Children of FDTC participants had a shorter length of time until permanent placement (360 days vs. 435 days) ◆ No difference in the probability of a subsequent child maltreatment report. |

| Worcel et. al. 2008 |

Location: 3 of the sites from the Green 2007a study Treatment: 183 families served through FDTCs Control: 736 families with substance use issues in traditional child welfare Comparison cases were drawn from A) mothers in FDTC sites who did not participate for a variety of reasons and b) from 2 counties without FDTC |

◆ No differences in likelihood of out- of-home placement (88% of FDTC sample vs. 86% of comparison sample) ◆ FDTC children spent less time than comparison spent in out-of-home placement (403 days vs. 493 days) ◆ Comparison children reached permanency faster than FDTC children (288 days vs. 228 days) ◆ FDTC children were more likely to reunify with original parent (69% vs. 39%) |

| Green et. al. 2009 |

Location: 4 site study (see Green 2007) Treatment: 739 FDTC parents (including 334 high intensity service recipients) Comparison cases: 1,307 parents drawn from the same site or similar counties near site; & met eligibility requirements for FDTC |

◆ FDTC parents had longer wait times until permanency relative to traditional court processing in Santa Clara ◆ In Washoe and Santa Clara, FDTC children spent more time with parents and fewer days in out-of-home placement than comparison children ◆ In Santa Clara, Washoe, and San Diego the FDTC children were more likely to be reunified with their parents |

| Dakof et. al. 2010 |

Location: Miami, FL 62 mothers randomly assigned to either usual drug court care (n=31) or the Engaging Moms drug court program (n=31) |

◆ A smaller percentage of FDTC participants had their parental rights terminated (23% vs. 44%) ◆ A higher percentage of FDTC participants regained custody (58% vs. 45%) |

| Burrus et. al. 2011 |

Location: Baltimore Treatment: 200 Family Recovery Program cases Control: 200 cases that entered child welfare with similar characteristics as the program |

◆ Children in families served by the program spent less time in care (252 days vs. 346 days) ◆ Children in treatment reached permanency faster (249 days vs. 325 days). ◆ Children of program participants were more likely to be reunified (70% vs. 45%) |

| Bruns et. al. 2012 |

Location: large city in Western U.S. Treatment: 76 FDTC participants Comparison: 76 parents in the same system who did not participate in the FDTC |

◆ FTDC children spent less time placed out of home (476 days vs. 689 days) ◆ FDTC children ended child welfare system involvement sooner (718 days vs. 689 days) ◆ FDTC children were more likely to return to parental care (55% vs. 29%) |

| Chuang et. al. 2012 |

Location: Hillsborough County FL Treatment: 95 FDTC participants Comparison A: 424 families from neighboring counties without an FDTC Comparison B: 95 matched comparison families |

◆ FDTC participants had a higher probability of reunification ◆ Time to permanency was longer for the unmatched cases. ◆ FDTC participants were less likely to re-enter care |

Another frequently asked question is, “Does FDTC participation affect the probability that youth are reunified with their parents?” Reunification and family preservation is generally considered a positive outcome—from both the civil rights perspective and the child development perspective (Lloyd & Barth, 2011). As evidence of this view, there are strict legal protections in place to regulate the removal of a child and the termination of parental rights (Huntington, 2006). In some cases of child neglect or abuse, protecting the child requires that the child be removed from the home and potential termination of parental rights. However, in many cases, professionals are not in agreement as to what constitutes the child’s best interest. Empirical research is emerging which supports family preservation as beneficial for children. For example, an analysis of data on children investigated for maltreatment examined the effect of out-of-home placement on adult outcomes such as criminal justice involvement and employment (Doyle, 2007, 2008). By using the variation in case workers’ propensity to remove youth or have them remain in their homes, these studies revealed that children who were removed were at increased risk of adult criminal justice involvement, delinquency, and becoming a teen mother.

Not all analyses, however, have reported such differences. An analysis of the National Survey of Adolescent Well-Being found no short-term positive or harmful effects of home removal on cognitive functioning or behavior problems (Berger, Bruch, Johnson, James, & Rubin, 2009). Empirical studies have documented that FDTC participants are more likely than comparison groups to be reunified with their children (see Table 1) or less likely to have their parental rights terminated (Dakof et al., 2010).

The empirical literature generally finds that participants in FDTC programs have higher reunification rates. However, to ensure that children are returning to a safe environment, it is important to examine children’s experiences upon returning home. Two outcomes that have been examined to address this issue include the probability of a substantiated maltreatment report following return home from foster care (Green, Furrer, et al., 2007) and the probability of re-entry into foster care after returning home (Ashford, 2004; Chuang et al., 2012). The results of these studies are mixed. Green, Furrer, et. al 2007 reported no difference in the probability of a substantiated re-report for child maltreatment, but Chuang et al. (2012) found that children whose parents participated in FDTC were less likely to re-enter foster care. Ashford (2004) found that these children were more likely to re-enter foster care.

Other important outcomes are adoption and return to the custody of a guardian. Although neither outcome refers to reunification, both are positive outcomes in that they are permanent and have been associated with long-term benefits to a child (Barth & Lloyd, 2010). Bruns et al. (2012) found that children of participants in FDTC programs were 2.5 times more likely to be returned to the custody of their guardian and were half as likely to remain in out-of-home placement, with a slightly higher rate of adoption than the comparison group.

It is difficult to determine the reason for differing results on similar outcomes. One key factor may be that the studies are evaluating different implementations of similar programs (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). Across communities, programs vary in the strength of partnerships between the court, social services, and substance use services; in the quality of substance use services; and in court supervision of substance services (Pach, 2008). Courts also operate within the context of their own state laws which can affect who enters an FDTC program and when participation begins. For example, courts in North Carolina only require that participants have a pending child abuse, neglect, or dependency case, while some other states use a post-adjudication model. Also, the use and type of sanctions employed can vary widely across courts (Edwards, 2010). One such variation is the use of jail as a sanction in FDTCs. Although jail is generally not advocated, some courts do use this as a motivational tool, although a more frequently used sanction is the threat of removal of custodial children.

The current study expands on previous work by examining variation in outcomes for a large sample of youth in foster care whose parents participated in a state-funded FDTC program. Our study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, to our knowledge, this study is the first statewide evaluation of FDTCs. There are several studies from single jurisdictions and studies in which a court’s participation in an evaluation is voluntary. In contrast, our study uses observational data from an administrative dataset in which FDTCs tracked information on participants for internal record-keeping purposes. Second, our analysis incorporates information from birth records. Data for this study come from three systems in North Carolina—social services, the courts, and vital statistics—and describe the experiences of individuals in 11 FDTCs. Previous studies have reported that information on birth records such as low birth weight and lack of timely prenatal care predicts future maltreatment exposure and child welfare outcomes (Needell & Barth, 1998; Putnam-Hornstein & Needell, 2011; Wu et al., 2004). Third, our study examines varying levels of participation in FDTC by comparing outcomes by highest level attained—being referred, enrolling in, and completing an FDTC program. This study is innovative in evaluating outcomes of persons who enroll in an FDTC program but do not complete and outcomes of completers. It is quite plausible that some exposure to FDTC programs is productive in improving outcomes. We use persons who were referred to an FDTC program but did not enroll in a program as a control group for our enrollment analysis. Persons who were referred but who did not enroll are likely to be more similar to enrollees than are children named in maltreatment reports who were not referred to FDTCs.

Methods

Data

The North Carolina Division of Social Services (DSS) data include information on all reports for child maltreatment and placements into foster care from January 2002-August 2011. Children were followed for 2 years through August 2013. The data include child identifiers ( name, birthdate, social security number, county of residence, and demographic characteristics e.g., gender and race/ethnicity). The maltreatment reports include date of report, investigation date, type of report (e.g., sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect), and contributing factors for report or placement (e.g., parental substance use and domestic violence). A subset of maltreatment reports lead to removal of children from the home and temporary placement in foster care. Information on foster care placements includes reason(s) for placement, living arrangements of the youth while in the care of social services, length of time in care, and characteristics of the removal home (e.g., family structure and information on how the youth exited care such as reunification with parent/caregiver and adoption).

Information on parental participation in the FDTC came from the NCAOC. The data identify the person who was referred to the program (name, birthdate, gender), the date referred, whether the individual enrolled in the program, completed the program, and the last attendance dates for non-completers. Information on participants’ children is often blank. However, we identified the participants’ children by linking the FDTC data to the corresponding birth records and social services records.

The birth records served as a link between the DSS and the FDTC data and provided information on key attributes known to predict youth outcomes, including maternal education and age at time of birth, receipt of prenatal care, and drug or alcohol use during pregnancy. Data included information on mother’s, father’s, and child’s first, middle, and last name; birthdate; race/ethnicity; and county of residence. Over 80% of the birth records have a father listed.

Data were not publicly available. Access to the data was obtained by requesting permission from each state agency to use and link the data by person identifiers. The Duke University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

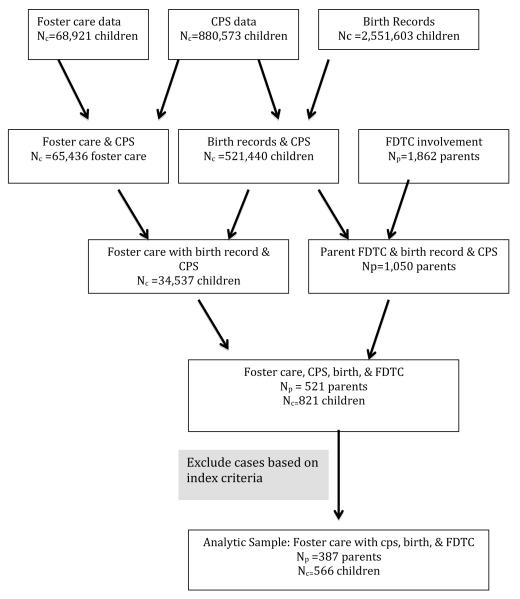

An integral empirical task involved merging information across systems (Figure 1). In step 1 child protection service records and foster care records were merged to create a full record of child’s experiences in the child welfare system. Both datasets were initially structured to make the observational unit a unique child. The datasets were then merged using child identifiers (e.g., first name, last name, birthdate). Child protection records were also merged with birth records using first and last name of the child, date of birth, and gender as the primary variables for merging purposes. For observations that did not merge, we used information on date of the child’s birthdate and last and first name assisted by the use of Soundex. (Soundex is an algorithm that codes words or names phonetically [Zizhong Fan, 2003].) Next, for the observations that remained, we relaxed the criterion of use of first name by substituting the first letter of the first name for the full first name. We used a similar approach to merge parent information from birth records with data from FDTC programs. After performing all the necessary merges, our dataset included 521 FDTC parents of 821 children.

Figure 1.

Description of Data Set Linking

Sample

For analytic purposes, an index maltreatment report was selected based on the timing of a parent’s referral to the FDTC, and only included reports within one year prior to FDTC referral. The sample was limited to reports that led to foster care placement within one year of the report of maltreatment. The time restriction was used so that FDTC participation was likely to be related to the child’s current case with child protection services. Referral to an FDTC does not occur years after a foster care or maltreatment report; rather, referral occurs within close proximity. Cases were dropped if placement in foster care occurred after the FDTC involvement was complete. The sample included 566 children from 387 families, including 157 children whose parent was referred but did not enroll, 215 children whose parent enrolled but did not complete, and 194 children whose parent completed. A child may have multiple documented allegations of maltreatment. If there were multiple allegations, the allegation that occurred most recently prior to FDTC enrollment was selected as the index maltreatment case.

Measures

The dependent variables, Yc,f, varied by child (c) in family (f). The dependent variables were: days spent in foster care, exit type for foster care (reunification, adoption, placement with guardian or custodian), and re-entry into foster care. Number of days spent in foster care was a continuous variable calculated by subtracting placement begin date from placement end date. Nearly all foster care stays in our sample of FDTC participants included an end date (97% of the total) and hence included type of exit—i.e., the reason that social services custody was terminated. A categorical variable identified whether the child was a) reunified with parent/caregiver, b) adopted, or c) placed in the custody or guardianship of the non-removal parent, a relative, or other court approved caretaker. Thirty children exited foster care for other reasons, including emancipation, runaway, or death. These children were excluded from analyses.

The first group of explanatory variables, FDTCc, included mutually exclusive categorical binary variables for the parent’s participation status in an FDTC: referred but not enrolled, enrolled but not completed, and completed. We defined referral to an FDTC from a referral date and the absence of an enrollment date in the FDTC data. Enrollment but not completion of an FDTC program was identified by presence of an enrollment date and absence of a completion date. Completion was identified by presence of a completion date.

The second category of covariates, FDTCparentc consisted of two binary variables indicating if the FDTC participating parent was under age 25 at the index maltreatment report date and the parent’s gender. Childc included covariates for race/ethnicity–White non-Hispanic (omitted reference group), Black non-Hispanic, Hispanic of any race/ethnicity, and other non-Hispanic. A binary variable indicated male gender. Age at maltreatment index maltreatment report was coded as four mutually exclusive binary variables: less than one year, one to three years, four to six years, and 7-18 years.

Third, we included binary variables describing characteristics from birth records (birthc): a child was of low or very low weight (<2,500 grams); late prenatal care if prenatal care was never initiated or initiated after the first trimester; presence of father if father was listed on the birth record; and maternal educational attainment (less than a high school diploma [omitted reference group], high school diploma, or higher education).

A fourth category included covariates describing characteristics of the index maltreatment report and initial entry into foster care (maltric). Child’s disability status as noted by the social services case worker was indicated by mutually exclusive binary variables for a) emotional or behavioral problem, b) other disability, or c) no disability listed (omitted reference group). A binary variable indicated whether an investigation substantiated the report of maltreatment. The foster care records included information on contributing factors that lead to the child being removed. A binary variable indicated if that child lived in a two-parent family or other (e.g., single parent, listed as “unable to determine”) at the time of removal. Mutually exclusive binary variables indicated if the child was removed because of a) physical or sexual abuse, b) parental substance use (no abuse), c) other factors (e.g., parental death, jail, mental health issues, child substance use, behavior), and d) neglect as the only factor listed (omitted reference group). Year of the index maltreatment report was included as an ordinal variable. A binary variable indicated whether the maltreatment report was substantiated by the social services agency.

The follow-up period for each group was two years. A two-year period was used primarily because child permanency outcomes must be completed within one year and FDTCs create treatment plans to accommodate the time restrictions of the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 (Pach 2008). We varied the start time of follow-up to prevent outcomes being measured prior to the start of treatment. For the referred group, follow-up began at the date of referral to an FDTC program. For the enrollment sample, follow-up began at the last known date of participation in the FDTC. For the completion sample, the follow-up period began at the date of completion.

Analysis

Bivariate relationships between children of parents who completed FDTC and both the referred and enrolled groups were calculated by conducting a t-test with unequal variances for the amount of time in foster care and year of index maltreatment report and a test of proportions for group differences in the dichotomous variables. In sum, our empirical analysis related foster care outcomes to FDTC participation and other factors likely to also affect these outcomes:

Estimation

Time to exit foster care was modeled using a hazard model (Blossfeld, Golsch, & Rowher, 2007). We assumed that the hazard rate followed a Weibull distribution. As a sensitivity test, a Gompertz distribution was also examined and yielded similar estimates (not reported). Children who were not observed exiting care were included in the analysis and treated as right censored at the last available date in the data (August 30, 2013). This occurred for 9% (14 children) of the referred sample but in none of the enrolled or completed sample.

We analyzed exit type with multinomial logistic regression to assess the competing risk of different ways that youth’s temporary custody terminated. The alternative exit types were: being adopted, exiting to guardianship/custody, or being reunified with parent or primary caregiver (the omitted reference group). Those who were not observed exiting or who exited in another way, e.g. death, were excluded from this analysis. All analyses were conducted in Stata SE version 11 (StataCorp), and standard errors were corrected to allow for intragroup correlation that may occur within families.

Results

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for the sample of children whose parents participated in the FDTC organized by type of participation (referred but not enrolled, enrolled but not completed, and completed). Differences between groups on the average time in foster care were not statistically significantly different based on parent’s participation in FDTC.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Youth in Foster Care by Parent’s Participation in Family Drug Treatment Court

| Referred (n=157) % |

Enrolled (n=215) % |

Completed (n=194) % |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | |||

| # of days in foster care | M=595.8 SD=468.5 |

M=646.7 SD=459.8 |

M=588.3 SD=302.7 |

| Exit outcomes | |||

| Reunified with parent | 32.5*** | 23.7*** | 72.7 |

| Adopted | 14.6†,*** | 25.6*** | 3.6 |

| Placed in custody or guardianship | 40.1*** | 47.4*** | 22.2 |

| Other resolution | 12.7†††,*** | 3.3 | 1.5 |

| Child Characteristics | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 46.5* | 53.5 | 58.8 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 36.9* | 27.4 | 24.7 |

| Other race, non-Hispanic | 11.5 | 15.3 | 13.9 |

| Hispanic | 5.1 | 3.7 | 2.6 |

| Female | 46.5 | 47.4 | 44.8 |

| Age at index maltreatment report | |||

| Less than 1 year | 21.0 | 26.5 | 23.7 |

| 1 to 3 years | 31.8 | 26.5 | 24.2 |

| 4 to 6 years | 19.7 | 17.2 | 13.4 |

| 7 to 18 years | 27.4* | 29.8 | 38.7 |

| Birth record information | |||

| Low or Very low birth weight | 18.5 | 22.8 | 23.7 |

| Prenatal care only initiated after first trimester | 29.3** | 34.4 | 42.8 |

| No father listed on the birth record | 35.7* | 32.6** | 46.4 |

| Maternal Education | |||

| Less than High School | 52.2 | 61.9 | 56.2 |

| High School Diploma or more | 47.8 | 38.1 | 43.8 |

| FDTC parent is female | 87.3** | 90.7 | 95.4 |

| Information from DSS Records | |||

| Child emotional or behavioral disability | 10.8 | 12.6 | 15.5 |

| Child other disability | 5.1 | 6.5 | 6.2 |

| Parent under 25 at index maltreatment report | 28.7** | 27.4** | 16.0 |

| Two parent home at time of removal (reference=single parent or unknown) |

36.3 | 27.0 | 30.4 |

| Reason for removal | |||

| Abuse | 5.1 | 4.2 | 4.6 |

| Parental Substance Abuse | 68.8† | 58.1 | 63.9 |

| Other factors | 12.1** | 7.4 | 4.1 |

| Neglect | 14.0†††,** | 29.8 | 26.3 |

| Year at index maltreatment report | M=6.9†,*** SD=2.1 |

M=6.4** SD=2.0 |

M=5.8 SD=2.1 |

| Substantiated index maltreatment report | 35.7* | 38.1 | 47.4 |

p0.05 vs. enrolled;

p0.01 vs. enrolled;

p0.001 vs. enrolled

p0.05 vs. completed;

p0.01 vs. completed;

p0.001 vs. completed

The reunification rate did not differ between the referred (33%) versus enrolled (24%) samples, but was much lower than the rate observed in the completion sample (73%). The adoption rate was lowest for the completion sample (4%), followed by the referred sample (15%), and was highest for the sample of parents who enrolled but did not complete (26%). Twenty-two percent of foster children of FDTC completers exited to custody or guardianship of a court approved caregiver; by contrast, the shares for children of parents referred but not enrolled (40%) and enrolled but not completed (47%) were considerably higher.

Relative to the completion sample, a smaller percentage of the referral sample was Black non-Hispanic (47% vs. 59%), and a larger percentage was White non-Hispanic (37% vs. 25%). A smaller percentage of children in the referred sample than the completion sample were in the oldest age group (27% vs. 39%). Information on the birth records suggested that children in the completion sample were at increased risk for poor outcomes relative to the referral sample, with a smaller percentage of children in the referral sample having late prenatal care (29% vs. 43%) or no father listed on the birth record (36% vs. 46%). Other statistically significant differences between the referral and completion samples included FDTC parent is female, parent under age 25 at time of maltreatment report, reason for removal, year of index offense, and proportion with a substantiated maltreatment report.

Few baseline covariates were statistically significantly different between children in the enrollment and completion samples. Relative to the completion sample, a smaller percentage of children of enrollees had no father listed on the birth record (33% vs. 46%) and a larger percentage had a parent who was under age 25 at the time of the index report (27% vs. 16%). On average, the year of index report was more recent for children in the enrolled sample than the completion sample.

Similarly, children in the referred and enrolled samples differed on just a few baseline characteristics. Parental substance use, as a reason for the maltreatment report, was higher in the referred than the enrolled sample (69% vs. 58%) while neglect was lower (14% vs. 30%). The year of index maltreatment report was also lower in the referred than the enrolled sample (6.9 vs. 6.4).

Time in Foster Care

Children whose parents were referred to a FDTC program but who did not enroll exited foster care 36% slower than children whose parents completed. Similarly, children of enrolled parents had statistically significant longer stays than children whose parents completed—they exited 27% slower than children of completers. Results of a Wald test indicated that the null hypothesis that rates of exiting foster care did not differ between children in the referred or enrolled samples could not be rejected (X2 = 0.73, p = .393). Relative to White non-Hispanic children, Black non-Hispanic children and children of other races had longer stays in foster care—exiting at 45% the rate of White children. School-aged children exited more slowly than infants. Children whose mothers were involved in a FDTC program rather than the father spent 36% more time in foster care on average.

Exit from Foster Care

Children whose parents completed a FDTC program were more likely to exit foster care by reunification compared to children whose parents were either referred but did not enroll or who enrolled but did not complete. Relative to children whose parents completed the FDTC program, children whose parents were referred but did not enroll or who enrolled but did not complete were 14 times and 32 times more likely to exit to adoption rather than reunification (Table 3). Compared to children of parents who completed an FDTC program, the relative risk of exiting foster care by being placed with a legal custodian or guardian rather than reunification was five times higher for children in referred sample than children in the completed sample and ten times higher for children of enrollees who did not complete. As evidenced by overlapping confidence intervals (not shown), differences between children in the referred and enrolled samples were not statistically significantly at p = .05 different on the risk of exiting a) toward adoption (vs. reunification) or b) toward legal custodian or guardian (vs. reunification).

Table 3.

Regression Results: Effect of FDTC Participation on Outcomes for Youth in Foster Care

| Hazard | Competing Risk (reference=reunification) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Exiting Foster Care HR (s.e.) |

Adoption RRR (s.e.) |

Guardian /Custodian RRR (s.e.) |

|

|

Parental FDTC participation:

(reference=Completed) |

|||

| Referred | 0.640** (0.102) |

13.811*** (10.494) |

5.448*** (1.990) |

| Enrolled | 0.731* (0.089) |

32.209*** (24.365) |

10.078*** (3.477) |

|

Child’s race/ethnicity:

(reference=White) |

|||

| Black non-Hispanic | 0.571*** (0.072) |

1.559 (0.769) |

0.352** (0.117) |

| Other race non-Hispanic | 0.567*** (0.097) |

1.237 (0.626) |

0.259** (0.110) |

| Hispanic | 0.506 (0.186) |

2.174 (1.717) |

0.535 (0.351) |

| Child female | 1.087 (0.089) |

0.872 (0.253) |

1.046 (0.242) |

|

Age at index maltreatment report

(reference=0 to 1): |

|||

| 1 to 3 | 0.940 (0.117) |

0.816 (0.352) |

1.508 (0.501) |

| 4 to 6 | 0.713* (0.102) |

0.798 (0.377) |

1.189 (0.478) |

| 7 to 18 | 0.699** (0.097) |

0.394 (0.199) |

2.011 (0.788) |

| Low or very low birth weight | 0.841 (0.093) |

1.852 (0.680) |

1.656 (0.481) |

| Prenatal Care initiated only after first trimester |

1.066 (0.096) |

0.916 (0.369) |

1.112 (0.277) |

| No father listed on birth records | 0.962 (0.123) |

1.878 (0.892) |

2.362** (0.781) |

| Maternal education at child’s birth is HS diploma or more |

1.021 (0.101) |

0.566 (0.188) |

0.771 (0.206) |

| FDTC parent is female | 0.637** (0.107) |

2.710 (2.058) |

3.036* (1.512) |

|

Child’s disability:

(reference=no disability) |

|||

| Emotional or behavioral | 0.968 (0.145) |

0.466 (0.299) |

0.416* (0.153) |

| Other disability | 1.004 (0.228) |

0.807 (0.726) |

0.404 (0.303) |

| Parent <25 at index maltreatment | 1.026 (0.128) |

0.550 (0.241) |

0.961 (0.309) |

| Two parents home at time of removal (reference=single parent or unknown) |

0.956 (0.119) |

0.689 (0.292) |

0.596 (0.206) |

|

Reason for removal:

(reference=neglect) |

|||

| Abuse | 0.851 (0.152) |

2.256 (2.029) |

1.929 (1.623) |

| Parental Substance Abuse | 1.016 (0.135) |

1.145 (0.444) |

1.353 (0.422) |

| Other reasons | 1.027 (0.253) |

0.313 (0.262) |

1.518 (0.756) |

| CPS year of report | 1.067* (0.032) |

0.929 (0.082) |

0.948 (0.069) |

| Substantiated maltreatment report | 0.810 (0.093) |

0.806 (0.334) |

0.705 (0.204) |

| Constant | 0.033** (0.041) |

0.152* (0.126) |

|

| N. of cases | 566 | 536 | 536 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001;

Note: 1. HR is hazard ratio; 2. RRR is relative risk ratio

Other child characteristics were also related to differences in the exit pattern. Black non-Hispanic children and children of other race were less likely than White non-Hispanic children to exit to guardianship or custody. When the FDTC parent was female, children were more likely to exit to guardianship/custody relative to reunification. Children with emotional or behavioral disabilities were less likely to exit to guardianship/custody relative to reunification.

Discussion

We found that parental completion of an FDTC was associated with reduced lengths of stay in foster care relative to the referred and enrolled samples. We expected that participation in an FDTC would yield positive benefits in terms of reunification rates for both the enrollment and completion groups. Instead, we found that the pattern of exit for foster care youth varied based on parental FDTC participation type. Children of completers were more likely to be reunified and less likely to exit via adoption or guardianship/custody relative to youth whose parents were referred to a FDTC program but who did not enroll or enrolled but did not complete. Children of parents who enrolled but did not complete experienced similar outcomes as children whose parents were referred but did not enroll. These children were more likely to exit toward adoption or legal guardianship or custody.

These findings are consistent with other studies that have found that treating parental substance use for children involved in the child welfare system can result in positive outcomes (Green, Rockhill, & Furrer, 2007; Grella, Needell, Shi, & Hser, 2009). By providing systems level integration, FDTCs create an environment in which the justice system and social services partner their efforts to address family needs. Although this study is based on data from one state, the results are applicable to similarly structured FDTCs in other states. FDTCs are relatively new, and our findings support the need for further research on the details of implementation to discover if the specific services provided and characteristics of the population served change the outcomes for children of participants.

The key limitation of this study relates to use of administrative data. The primary disadvantage of such data is the lack of rich contextual information often available in survey data. Thus, we were unable to control for differences between the FDTC participants on such factors as motivation for treatment, social support, mental health, and financial wellbeing. These factors may differ between individuals who chose not to enroll in this voluntary program and those who enrolled and/or completed the program. Differences in these factors could be related both to willingness to participate in an FDTC and ability to regain custody quickly. Another limitation is that we excluded children who were not born in North Carolina, and we were unable to track children who moved across state borders.

Nevertheless, administrative data offer some important strengths not likely to be present in studies based on survey data. In our study, control group families resided in the same counties as the families of the FDTC completers. Some previous studies have drawn comparison children from different counties (e.g., Chuang et al., 2012; Green et al., 2009). However, length of time in foster care and reunification has been shown to vary appreciably by geographic location (Courtney & Hook, 2012; Worcel et al., 2008). Another advantage of statewide administrative data is that results are not biased by selection of programs that agree to be evaluated. No matter how careful researchers are in selecting their control groups and research design—limiting evaluations to organizational units that agree to be included could lead to a selection of the best programs. Because inclusion in this study was not based on individual courts’ agreement to participant in our research, results presented here lend even stronger support to the effectiveness of the FDTC model.

Although emerging evidence suggests that these programs are effective, over the last 20 years, diffusion of these programs has been slow. Although operating in 43 states and the District of Columbia, there were only 323 FDTCs in 2012, as compared to 1,438 adult drug treatment courts (American University School of Public Affairs, 2012; National Drug Court Resource Center, 2012). Internationally, the United Kingdom has one established program, and as of 2013, two more courts were planned (Pemberton, 2013). Moreover, our results suggest that even in places where FDTC programs exist, enrollment and completion rates tend to be relatively low. Although effective substance use treatment services for parents may help preserve families (Grant et al., 2011; Green B, Rockhill , et. al 2007), not all substance use services implemented with public dollars aimed at this population are effective (Brook & McDonald, 2007). A recent study of 43 treatment programs found that women who participated in programs with high levels of family-related or education/employment services were more than twice as likely to reunify with their children as were women who participated in programs with lower levels of these services (Grella et al., 2009). The current study adds support to a small but emerging body of evidence indicating that substance use treatment promotes foster care children’s reunification with a parent or primary caregiver and shortens time in foster care. Future research should examine factors for improving take-up and completion rates as well as factors involved in scaling programs so that more families are served.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grant 5R01DA032548-02 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse. There are no conflicts of interest to be reported with this manuscript. We thank the North Carolina Administrative Office of the Courts for providing us with data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Joanne Gifford, Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University Box 90545 214 Rubenstein Hall 302 Towerview Rd. Durham, NC 27708.

Lindsey Morgan Eldred, Lindsey.eldred@duke.edu Department of Economics, Duke University.

Allison Vernerey, Allison.vernerey@duke.edu Department of Economics, Duke University.

Frank Allen Sloan, fsloan@duke.edu Department of Economics, Duke University.

References

- American University School of Public Affairs BJA Drug court technical assistance/clearinghouse project summary of drug court activity by state and county juvenile/family drug courts. 2012 Nov 30; Retrieved from http://www.american.edu. [Google Scholar]

- Ashford J. Treating substance-Abusing parents: A study of the Pima County family drug court approach. Juvenile and Family Court Journal. 2004;55:27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bambrough S, Shaw M, Kershaw S. The Family Drug and Alcohol Court service in London: a new way of doing Care Proceedings. Journal of Social Work Practice. 2013:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard M, McKeganey N. The impact of parental problem drug use on children: what is the problem and what can be done to help? Addiction. 2004;99:552–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth R, Lloyd E. Five-year developmental outcomes for young children remaining in foster care, returned home, or adopted. In: Fernandez E, Barth RP, editors. How does foster care work? International evidence on outcomes. Jessica Kingsley; London, England: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Berger L, Bruch S, Johnson E, James S, Rubin D. Estimating the “impact” of out-of-home placement on child well-being approaching the problem of selection bias. Child Development. 2009;80:1856–1876. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld H, Golsch K, Rowher G. Semiparametric transition rate models. In: Blossfeld H-P, Golsch K, Rowher G, editors. Event history with stata. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Boles S, Young N, Moore T, DiPirro-Beard S. The Sacramento dependency drug court: Development and outcomes. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:161–171. doi: 10.1177/1077559507300643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook J, McDonald T. Evaluating the effects of comprehensive substance abuse intervention on successful reunification. Research on Social Work Practice. 2007;17:664. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns E, Pullmann M, Weathers E, Wirschem M, Murphy J. Effects of a multidisciplinary family treatment drug court on child and family outcomes: Results of a quasi-experimental study. Child Maltreatment. 2012;17:218–230. doi: 10.1177/1077559512454216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Assistance. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. National Drug Court Institute Family dependency treatment courts: Addressing child abuse and neglect cases using the drug court model. 2004. pp. 1–82.

- Burrus SWM, Mackin JR, Finigan MW. Show Me the Money: Child Welfare Cost Savings of a Family Drug Court. Juvenile and Family Court Journal. 2011;62(3):1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6988.2011.01062.x. [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersen MN, Soothill K. The long-term consequences of parental alcohol abuse: A cohort study of children in Denmark. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;25:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang E, Moore K, Barrett B, Young M. Effect of an integrated family dependency treatment court on child welfare reunification, time to permanency and re-entry rates. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34:1896–1902. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney M, Hook J. Timing of exits to legal permanency from out-of-home care: The importance of systems and implications for assessing institutional accountability. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34:2263–2272. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham S, Finlay K. Parental substance use and foster care: Evidence from two methamphetamine supply shocks. Economic Inquiry. 2013;51(1):764–782. [Google Scholar]

- Dakof G, Cohen J, Henderson C, Duarte E, Boustani M, Blackburn A, Hawes S. A randomized pilot study of the Engaging Moms Program for family drug court. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;38:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bortoli L, Coles J, Dolan M. Parental substance misuse and compliance as factors determining child removal: A sample from the Victorian Children’s Court in Australia. Children and Youth Services Review. 2013;35:1319–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ. Child protection and child outcomes: Measuring the effects of foster care. American Economic Review. 2007;97(5):1583–1610. doi: 10.1257/aer.97.5.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ. Child protection and adult crime: Using investigator assignment to estimate causal effects of foster care. The Journal of Political Economy. 2008;116(4):746. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41:327–351. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn M, Tarter R, Mezzich A, Vanyukov M, Kirisci L, Kirillova G. Origins and consequences of child neglect in substance abuse families. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:1063–1090. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards L. Sanctions in family drug treatment courts. Juvenile and Family Court Journal. 2010;61:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Grant T, Huggins J, Graham JC, Ernst C, Whitney N, Wilson D. Maternal substance abuse and disrupted parenting: Distinguishing mothers who keep their children from those who do not. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33:2176–2185. [Google Scholar]

- Green B, Furrer C, Worcel S, Burrus S, Finigan M. How effective are family treatment drug courts? Outcomes from a four-site national study. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:43–59. doi: 10.1177/1077559506296317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green B, Furrer C, Worcel S, Burrus S, Finigan M. Building the evidence base for family drug treatment courts: Results from recent outcome studies. Drug Court Review. 2009;6:53–82. [Google Scholar]

- Green B, Rockhill A, Furrer C. Does substance abuse treatment make a difference for child welfare case outcomes? A statewide longitudinal analysis. Children and Youth Services Review. 2007;29:460–473. [Google Scholar]

- Grella C, Needell B, Shi Y, Hser Y. Do drug treatment services predict reunification outcomes of mothers and their children in child welfare? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:278–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-McKoy D, Meyer A, McWey L, Henderson T. Substance use, policy, and foster care. Journal of Family Issues. 2013:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Harwin J, Ryan M, Tunnard J, Pokhrel S, Alrouh B, Matias C, Schneider M. The Family drug and alcohol court (FDAC) evaluation project. Nuffield Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher KW, Mason J, Rubin J. Abuse, neglect, dependency, and termination of parental rights proceedings in North Carolina. 2011 *http://www.nccourts.org. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington C. Rights myopia in child welfare. Colorado Law Legal Studies Research Paper Series. 2006. pp. 1–64.

- Laslett A, Room R, Dietze P, Ferris J. Alcohol’s involvement in recurrent child abuse and neglect cases. Addiction. 2012;107:1786–1793. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine G. A study of family drug treatment courts in the United States and the United Kingdom: Giving parents and children the best chance of reunification. Victoria, Australia: The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust of Australia: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd E, Barth R. Developmental outcomes after five years for foster children returned home, remaining in care, or adopted. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33:1383–1391. [Google Scholar]

- Manning V, Best DW, Faulkner N, Titherington E. New estimates of the number of children living with substance misusing parents: Results from UK national household surveys. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:377. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Drug Court Resource Center How many drug courts are there? 2012 Retrieved from http://www.ndcrc.org. [Google Scholar]

- Needell B, Barth R. Infants entering foster care compared to other infants using birth status indicators. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22:1179–1187. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina Administrative Office of the Courts Target population and eligibility. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.nccourts.org.

- North Carolina Administrative Office of the Courts FDTC legal forms and procedures. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.nccourts.org.

- Pach N. An overview of operational family dependency treatment courts. no. 1. Vol. 6. National Drug Court Institute; Alexandria, Virginia: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton C. Family drug and alcohol courts to be rolled out across the UK. 2013 Retrieved from The Children’s Services Blog: http://www.communitycare.co.uk.

- Putnam-Hornstein E, Needell B. Predictors of child protective service contact between birth and age five: An examination of California’s 2002 birth cohort. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33:1337–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies . The NSDUH: Children living with a substance-dependent or substance-abusing parents: 2002 to 2007. Author; Rockville, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Scott DA. The landscape of child maltreatment. The Lancet. 2009;373(9658):101–102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61702-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. Author; College Station, TX: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh CA, MacMillan HL, Jamieson E. The relationship between parental substance abuse and child maltreatment: findings from the Ontario Health Supplement. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27(12):1409–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.07.002. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worcel S, Furrer C, Green B, Burrus S, Finigan M. Effects of family treatment drug courts on substance abuse and child welfare outcomes. Child Abuse Review. 2008;17:427–443. [Google Scholar]

- Worcel S, Green B, Furrer C, Burrus S, Finigan M. Family treatment drug court valuation. NPC Research; Portland, Oregon: 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Ma C, Carter R, Ariet M, Feaver E, Resnick M, Roth J. Risk factors for infant maltreatment: a population-based study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:1253–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young NK, Boles SM, Otero C. Parental substance use disorders and child maltreatment: overlap, gaps, and opportunities. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:137–149. doi: 10.1177/1077559507300322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zizhong Fan W. Matching character variables by wound: A closer look at SOUNDEX function and Sounds-Like Operator (=*) 2003. pp. 1–3.