Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to investigate suitable conditions of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) and micronucleus (MN) as genotoxic biomarkers at different levels of occupational chromate exposure.

Design

A cross-sectional study was used.

Participants

84 workers who were exposed to chromate for at least 1 year were chosen as the chromate exposed group, while 30 non-exposed individuals were used as controls.

Main outcome measures

Environmental and biological exposure to chromate was respectively assessed by measuring the concentration of chromate in the air (CrA) and blood (CrB) by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS) in all participants. MN indicators, including micronucleus cell count (MNCC), micro-nucleus count (MNC), nuclear bridge (NPB) and nuclear bud (NBUD) were calculated by the cytokinesis-block micronucleus test (CBMN), while the urinary 8-OHdG was measured by the ELISA method and normalised by the concentration of Cre.

Results

Compared with the control group, the levels of CrA, CrB, MNCC, MNC and 8-OHdG in the chromate-exposed group were all significantly higher (p<0.05). There were positive correlations between log(8-OHdG) and LnMNCC or LnMNC (r=0.377 and 0.362). The levels of LnMNCC, LnMNC and log (8-OHdG) all have parabola correlations with the concentration of CrB. However, there was a significantly positive correlation between log (8-OHdG) and CrB when the CrB level was below 10.50 µg/L (r=0.355), while a positive correlation was also found between LnMNCC or LnMNC and CrB when the CrB level was lower than 9.10 µg/L (r=0.365 and 0.269, respectively).

Conclusions

MN and 8-OHdG can be used as genotoxic biomarkers in the chromate-exposed group, but it is only when CrB levels are lower than 9.10 and 10.50 µg/L, respectively, that they can accurately reflect the degree of genetic damage.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Only when the concentration of chromate in blood (CrB) was lower than 9.10 and 10.45 μg/L, respectively, that MN and 8-OHdG can be used as effective biomarkers to show the degree of genetic damage.

If the concentration of CrB was higher than 9.10 and 10.45 μg/L respectively, the cytotoxic effect might play an important role and the cells with serious genetic damage may turn into apoptosis or necrosis, which could lead to the lower degree of MN and 8-OHdG.

The sample size of this study was not very large, especially of the control group, so we chose some references to give the values of MN and 8-OHdG in a normal population to reduce the generation of bias. More sample size epidemiological surveys in different chromate-producing factories should be chosen to verify our conclusion.

Introduction

Chromate is a widely used chemical in industrial and agricultural production in China, which could generate many pollutants including waste water, gas and residue in its production, usage, transportation and storage. Previous studies have shown that chromate exposure in the occupational workplace could affect the health status of workers, even increasing the incidence of cancer. For this reason it has been declared a well-known environmental and occupational hazard.1

There are many different valences of chromate, in which the hexavalent chromate (Cr-VI) is the most harmful one. Cr-VI can enter the human body mainly by inhalation during occupational activities. When entering into the respiratory system (nose, bronchial and lung), some Cr-VI could accumulate in the bronchoalveolar lining fluid, mucosa and pulmonary tissues1 2 and then cross the cell membrane through non-specific phosphate/sulfate anionic transporters to the blood. This transformation also can consequently form many reactive intermediates (Cr-V, Cr-IV and Cr-III) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) with oxidative stress.3 4 Both Cr-III and ROS could contribute to the interaction with various biological macromolecules such as Cr-DNA adducts, Cr-protein adducts and protein-Cr-DNA adducts. This can cause damage to the DNA and chromosome including base modification, single-strand breaks and double-strand breaks. These changes can result in genetic damage and ultimate carcinogenesis if accumulated to some degree.5–7

Based on the evidence above, many studies have proved that 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) can be used as a biomarker to assess the oxidative damage and DNA mutations that are induced by the ROS in clinical,8 environmental9 10 and occupational settings in vitro11 12 or in cell cultures.13 Micronucleus (MN) in peripheral blood was another biomarker to show genetic damage. It originates from chromosome fragments that are attacked by certain physical and chemical factors such as chromate or whole chromosomes that lag behind at anaphase during nuclear division. When the excision reparable DNA lesions are induced in the G0/G1 phase, they can be converted to MN by using inhibitors of the gap filling step of excision repairmen, so that unfilled gaps are converted to double-strand breaks after the S phase,14 so the frequency of MN can be used to reflect genetic damage.15 The CBMN test is a common method to detect the MN frequencies including many indexes such as MNCC, MNC, NPB and NBUD. In these indexes, MNCC and MNC were commonly used to detect DNA damage.14

Previous studies have discussed the relationship between chromate in blood (CrB) and urinary 8-OHdG or MN in the chromate-exposed group to investigate the feasibility of 8-OHdG and MN as genetic damage biomarkers. However, the conclusion about this connection has yielded conflicting results: Kuo found that there was linear correlation between urinary 8-OHdG and CrB,16 but Gao, Kim and Zhang did not confirm this subsequently.17–19 Other research has identified some association between CrB and MN frequencies,20–22 but the suitable conditions and limitations of 8-OHdG and MN as genotoxic biomarkers for occupational chromate exposure have still been unclear. Therefore, our researches aimed to observe the effect of chromate exposure on genetic damage in occupational workers, especially urinary 8-OHdG for the oxidative DNA damage and MN for chromosome damage. We discuss whether MN frequency and 8-OHdG can be used as effective genotoxic biomarkers at different levels of chromate exposure.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

A cross-sectional survey was designed for this research. The factory was chosen as the workplace in Henan province in China because (1) the product potassium dichromate was relatively simple, most of which was water-soluble hexavalent chromate and (2) annual health check-ups were offered in this factory for workers, which allowed us to easily collect specimens to minimise the interference with normal work schedules.

In this research, 84 workers exposed to chromate in the factory were chosen as the exposed group, while 30 non-exposed individuals working in the administration office were chosen as the control group. The criteria used in selecting participants were: (1) workers in the exposed group employed for at least 1 year and in the same work position for at least 3 months; (2) aged between 25 and 50 years; (3) no medical history of allergy, asthma or allergic rhinitis; (4) all participants with skin infections, fever or other clinical diseases should be excluded during the sampling period; and (5) pregnant and nursing women were not enrolled.

All participants were in the same factory with similar education and social backgrounds. All of them were required to complete a questionnaire and had a clinical examination before sample collection. The questionnaire included a lot of information such as occupational history, personal medical history, medication used in the 4 weeks before the study, body weight and height, hair dye, house decoration, radiation exposure, individual protection, smoking status, and alcohol intake.

Air and biological exposure assessment

According to the sampling criteria in the monitoring of hazardous substances in the air (GBZ 159-2004),23 six air sampling sections were respectively chosen in the workplaces of two groups, and 10 sampling points were chosen in each section. The sampling process involved pumping at 1 L/min for 8 h (Sp730, TSI Corporation). The membranes used in this study were MCE mixed cellulose ester filters (Φ37 mm, pall, America). The average concentration of all sampling points on the membranes in the same group was measured by atomic absorption spectrometry24 and then calculated to evaluate the CrA during the whole production process; the detection limit for the CrA was 0.001 μg/L.

Four millilitres of anticoagulant (EDTA and heparin) peripheral blood was drawn from each participant after finishing the questionnaire and then assigned to these two tubes on average. They were respectively used to measure the CrB and CBMN. The concentration of CrB was measured by an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS).24 The detection limit was 0.0012 μg/L.

At the end of the work shift, 30 mL of the urine sample of each participant was collected into a 50 mL metal-free polypropylene centrifuge tube (Falcon, BD Biosciences) and stored at −80°C until used.

The tubes that were used in this study had their background value detected before the research was carried out to ensure less element and heavy metal contamination.

Determination of urinary 8-OHdG

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, urine samples were first centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 7 min; second, the supernatant was chosen to determine the content of urinary 8-OHdG using an ELISA kit (USA Cayman chem, USA Cayman chem, 8-OHdG EIA kit) by Multiskan MK3 (Thermo, USA).The concentration of Cre in urine was determined by alkaline picric acid assay with a commercial kit (Ausbio Laboratories Co., Ltd. China) using a Hitachi 7170A automatic analyser (Hitachi Corp, Japan). The results of 8-OHdG were regulated by Cre to avoid the potential interference of a different urine density among participants.

CBMN test

Peripheral venous blood in heparin tubes was taken to measure the MN frequency. The indexes (MNCC, MNC, NPB and NBUD) were counted in 1000 binuclear lymphocytes of each individual according to Fenech's protocol.25 All scoring was carried out by two independent researchers through the double-blind method. If the difference of scoring values from these two researchers was less than 20%, the average was calculated as the final result. If the difference in scores from these two researchers was more than 20%, another researcher was asked to verify the scores the average is taken after removing the most different value.

Statistical analysis

Epidata V.3.0 software was used to enter the questionnaire and experimental data into the computer. The whole process utilised a double-entry and logistical error check to ensure accuracy.

All analyses were performed with SPSS V.16.0. Normality was assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test; the variables including 8-OHdG, MNCC and MNC did not meet the normality, so Log or Ln transformation was made for normality approximation. Continuous and categorical parameters between the chromate-exposed group and control group were tested using the two sample t test (or Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test) and χ2 test. Curving correlation and linear regression were performed. Statistical significance was two sided. p Values were defined as α<0.05.

Results

General information analysis

A total of 114 participants including 84 chromate-exposed workers (mainly in the form of K2Cr2O7) and 30 controls were recruited in this study. The working age of the chromate-exposed group was (7.82±5.51) years. Furthermore, the personal protection (gloves and masks) of workers was above 90%. The demographic characteristics of all participants in this research are presented in table 1, which showed that there were no significant differences in the distribution of gender, age, smoking and alcohol consumption between these two groups.

Table 1.

Results of the chromate-exposed group and control group

| Indexes | Group | Exposed group | Control group | T | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=84) | (n=30) | |||||

| Age |

±S ±S |

35.73±7.85 | 34.83±8.83 | 0.432 | 0.666 | |

| ≤35 | n (%) | 40 (47.62) | 17 (56.67) | 0.187 | 0.493 | |

| >35 | 44 (52.38) | 13 (43.33) | ||||

| Gender | n (%) | |||||

| Male | 62 (73.81) | 19 (63.33) | 0.869 | 0.351 | ||

| Female | 22 (26.19) | 11 (36.67) | ||||

| Smoke | n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 30 (35.71) | 8 (26.67) | 0.610 | 0.435 | ||

| No | 54 (64.29) | 22 (73.33) | ||||

| Alcohol | n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 29 (34.52) | 16 (53.33) | 2.530 | 0.092 | ||

| No | 55 (65.48) | 9 (46.67) | ||||

| CrA |

±S ±S |

15.45±19.00 | 0.23±0.38 | 6.963 | <0.001 | |

| CrB |

±S ±S |

9.45±9.47 | 4.05±1.87 | 3.215 | 0.018 | |

| 8-OHdG (µg/g Cre) (‰) |

±S ±S |

43.76±34.89 | 27.21±13.76 | 3.354 | <0.001 | |

| MNCC | M(Q) | 6.00 (4.00) | 3.20 (2.10) | 2.420 | 0.004 | |

| MNC | M(Q) | 7.40 (4.47) | 3.74 (2.94) | 3.401 | 0.001 | |

| NBUD | M(Q) | 1.11 (1.20) | 1.16 (1.17) | 0.163 | 0.871 | |

| NPB | M(Q) | 1.28 (1.15) | 1.42 (1.34) | 0.476 | 0.635 |

Note: ‘Smoke’ refers to ≥1 cigar per day and last >1 year; smoking cessation <1 year were also included.

‘Alcohol’ refers to alcohol consumption ≥3 times per week.

Concentration of CrA and CrB

As shown in table 1, the concentration of CrA in the chromate-exposed group ((15.45±19.00) μg/m3) was much higher than that in the control group ((0.23±0.38) μg/m3, p<0.001), but still under the exposure limitation of chromate ((50 μg/m3) (2012, ACGIH)). The levels of CrB in the chromate-exposed group ((9.45±9.47) μg/L) were also significantly higher than those in the control group ((4.05±1.87) μg/L).

Levels of urinary 8-OHdG and serum CBMN indexes

The data distribution of indexes such as 8-OHdG, MNCC, MNC, NBUD and NPB was shown in table 1; the levels of 8-OHdG, MNCC and MNC were all significantly higher in the chromate-exposed group than those in the control group (p<0.05), which showed that 8-OHdG, MNCC and MNC could be used as the genetic damage biomarkers caused by chromate exposure.

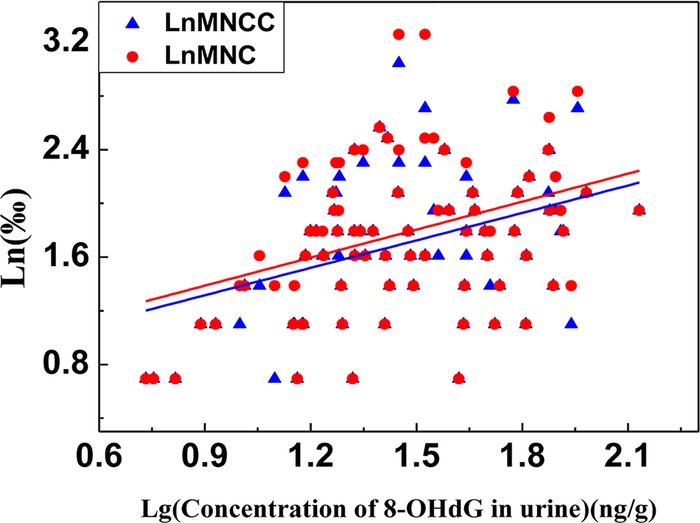

Correlation

As the two biomarkers for genetic damage, there was a positive correlation between log (urinary 8-OHdG) and LnMNCC or LnMNC (r=0.377 and 0.362, respectively; p<0.05) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Correlation between LnMNCC or LnMNC with Lg (concentration of 8-OHdG in urine) in the chromate-exposed group.

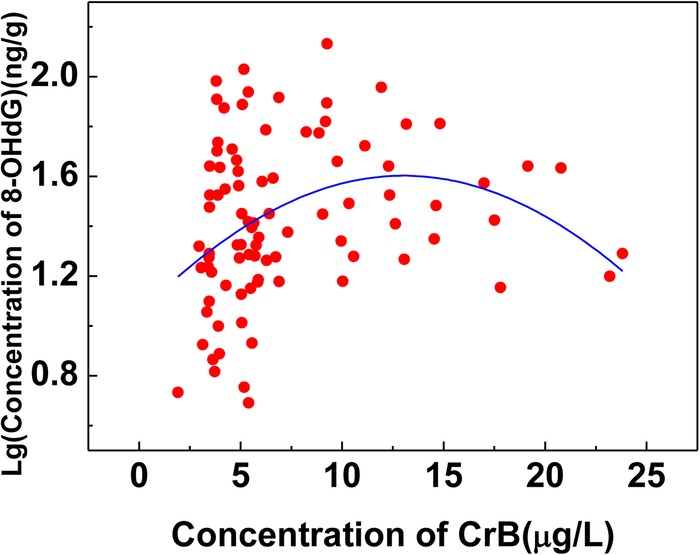

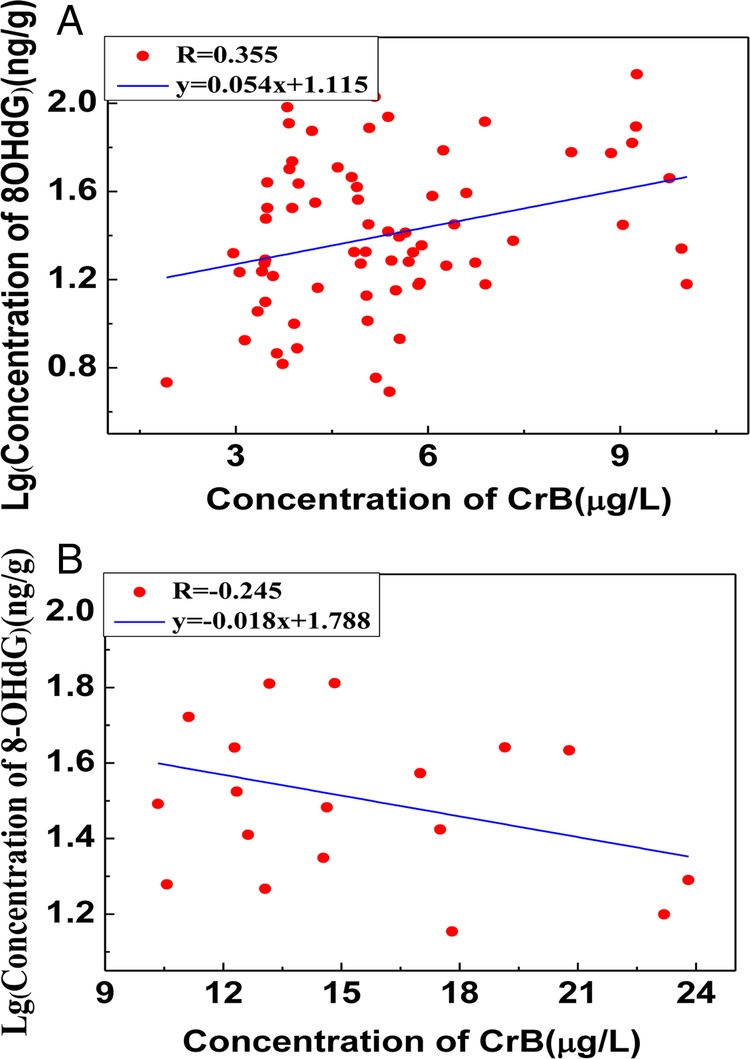

Correlation was also analysed between the concentration of urinary 8-OHdG and CrB. As was recorded in figures 2 and 3, there was no linear correlation but a curve fitting between CrB and log (8-OHdG), whereas the value of 8-OHdG was decreased when the concentration of CrB was more than 10.50 mg/L. Based on the results above, the concentration of CrB was stratified into two groups: the high-exposed group (CrB ≥10.50 mg/L) and the low-exposed group (CrB <10.50 mg/L). A positive correlation was shown between CrB and log (8-OHdG) when the CrB level was lower than 10.50 mg/L (r=0.355, p<0.05), while there was a negative correlation between CrB and log (8-OHdG) when the CrB level was higher than 10.50 mg/L.

Figure 2.

Correlation between urinary 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) and chromate in blood (CrB) in the chromate-exposed group.

Figure 3.

(A) The correlation between urinary 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) and chromate in blood (CrB) in the higher chromate-exposed group (CrB≥10.50). (B) The linear relationship between urinary 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) and CrB in the lower chromate-exposed group (CrB<10.50).

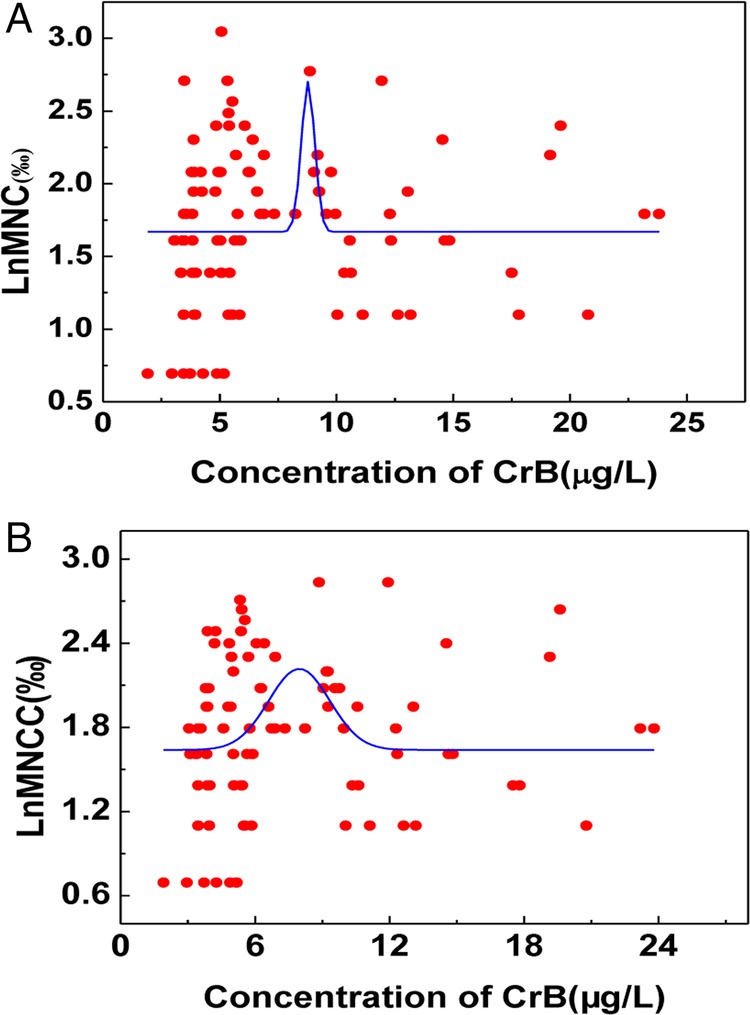

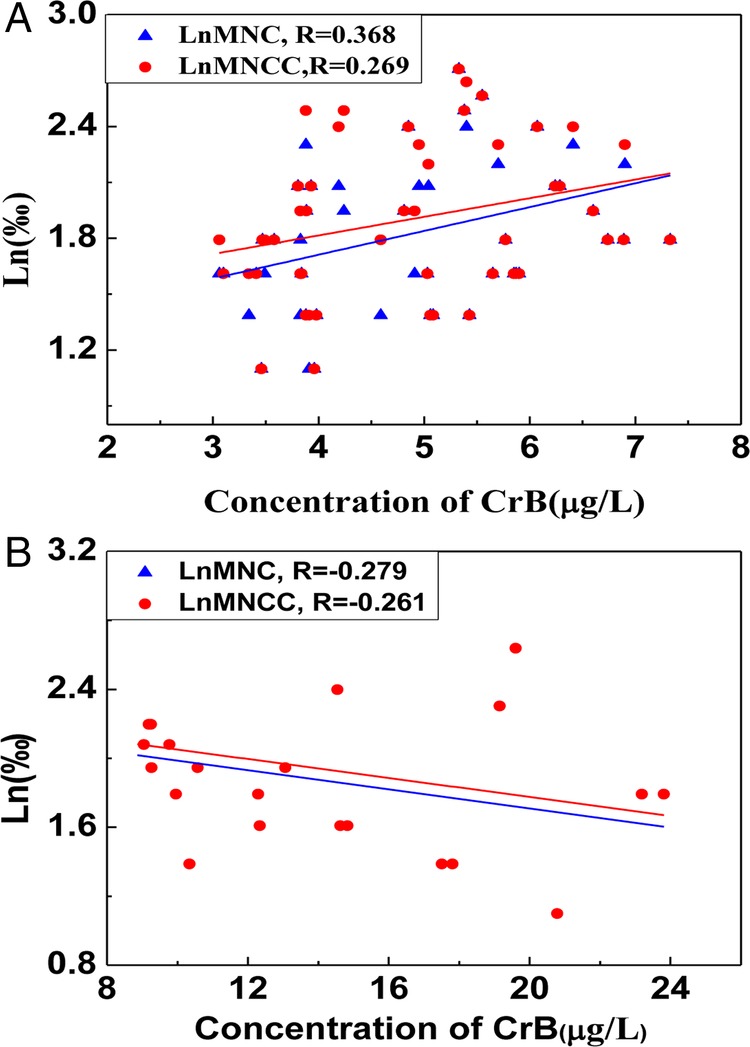

The relationship between the concentration of MNCC or MNC and CrB was also analysed in this research (figures 4 and 5). There was no linear correlation but a curve fitting between CrB and LnMNCC or LnMNC. The value of MNCC or MNC was decreased when the concentration of CrB was more than 9.10 mg/L. Based on the results above, the concentration of CrB was stratified into two groups: the high-exposed group (CrB ≥9.10 mg/L) and the low-exposed group (CrB <9.10 mg/L). A positive correlation was shown between CrB and LnMNCC or LnMNC in the higher chromate-exposed group (r=0.365 and 0.269 respectively, p<0.05), while a significantly negative relationship was found between CrB and LnMNCC or LnMNC in the lower chromate-exposed group (r=−0.279 and −0.261 respectively, p<0.05).

Figure 4.

Correlation between LnMNC or LnMNCC and chromate in blood (CrB) in the chromate-exposed group.

Figure 5.

(A) The correlation between LnMNC or LnMNCC and chromate in blood (CrB) in the higher chromate-exposed group (CrB≥10.50). (B) The linear relationship between LnMNC or LnMNCC and CrB in the lower chromate-exposed group (CrB<10.50).

Discussion

Long-term and low-level chromate exposure can not only increase the body’s internal load but also cause a variety of harmful effects on workers’ health, even increasing the incidence of human cancer.26 27 In occupational activity, chromate could enter into the workers body mainly through the respiratory system, then be metabolism and excreted in the urine, so our previous researches have proved that the concentration of chromate in whole blood and urine can be used as indicators to assess chromate biological exposure.6 28 In this study, it was found that the concentrations of CrA and CrB in the exposed group were all significantly higher than those in the control group (p<0.05) ,while the CrB level in the chromate-exposed group was nine times more than that in the general population of our country (1.19 μg/L),29 which showed that the conclusion was credible by contrasting the genetic damage indexes between the chromate-exposed group and control group.

It is well known that Cr-VI can cross the cell membranes through non-specific phosphate/sulfate anionic transporters to the blood, it is then converted into other valence chromate compounds such as Cr-III, which could not only produce a large amount of ROS that can cause the redox system imbalance, but also directly or indirectly coordinate with DNA or protein. The above transformation can affect genetic stability including oxidative DNA lesion, DNA crosslinks, single-strand and double-strand breaks and so on.30–32 Besides, long-term chromate exposure can also cause cyto-toxicity to lead cells apoptosis.33

Urinary 8-OHdG has been demonstrated as a biomarker for oxidative DNA damage in chromate exposure not only by animal experiment but also by many epidemiological researches,34 35 because it is the site that ROS often attacks, but the dose–response relationship with occupational exposure indicators was not depicted clearly. In this research, the relationship between urinary 8-OHdG and CrB reflected two-way changes. The concentration of urinary 8-OHdG was not significantly increasing when the level of CrB was more than 10.50 mg/L, which showed that the concentration of 8-OHdG in urine would fail to predict the degree of DNA damage when the CrB was higher than some degree. There are some reasons for this result. First, Sumner has proved that oxidative DNA damage by chromate exposure mainly targets specifically certain glycol tic enzymes on 8-OHdG,36 which means that once a higher burden of CrB is produced, it could oxidise and change the structure of glycolytic enzymes to reduce the production of free 8-OHdG. Second, some researchers have proved that 8-OHdG was not the final product of redox reaction, so when the level of CrB was higher, 8-OHdG could be converted to these further oxidation products such as Spiroiminodihydantoin (Sp),37 and therefore the concentration of free 8-OHdG was reduced. Third, the kidney can be damaged by chronic chromate exposure, this can also cause changes in the concentration of 8-OHdG in urine. As the level of CrB increased, the kidney was at a greater health risk, which ultimately affected the exertion of 8-OHdG in urine.38

Micronuclei is also commonly used as the genotoxic biomarker in the chromate exposed group.39 40 Many researches showed that chromate exposure could cause an increase of MN frequency in cell research, animal experiments and human beings.41 42 In this research, a similar conclusion proved that the MN frequency was significantly higher in the chromate-exposed group than that in the control group and the general population43 44(p<0.05). The frequencies of MNCC and MNC (as the sensitive indexes of MN) have statistical differences between these two groups. However, the relationship between MN indicators with CrB still needs further investigations; the reported research is meaningful to discuss the suitable condition of MN as genetic damage. In this study, no linear correlation was shown between CrB and LnMNCC or LnMNC, and the MN frequency did not increase as the CrB elevated. When all participants were divided into two subgroups by the concentration of CrB, a positive correlation was shown between CrB and LnMNCC and LnMNC in the high CrB group(CrB≥9.10 mg/L) (r=0.365 and 0.269, respectively), while a significantly inverse relationship was found between CrB with LnMNCC and LnMNC in the low CrB group (CrB<9.10 mg/L; r=−0.279 and −0.261, respectively). The reason for these results may be that the occupational chromate exposure can increase the frequency of the MN in some range. When the concentration of CrB is too high, the cytotoxic effect might play an important role and the cells with serious genetic damage may undergo apoptosis or MN.45 46

Both MN and urinary 8-OHdG can be used to predict different types of DNA damage in some range. There was a positive correlation between urinary 8-OHdG and MN, which suggested that these two indicators as genotoxic biomarkers can verify each other.

There was still some limitation in this study: the sample size of this study was not very large, especially the control group, so we chose some references38 43 44 to give the value of 8-OHdG and MN in a normal population to reduce the generation of bias. Also, it is necessary that more sample size epidemiological surveys in different chromate producing factories should be chosen to verify our conclusion.

Conclusions

New insights that both MN and urinary 8-OHdG can be used as the genetic damage biomarkers caused by occupational chromate exposure at some levels have been provided. The combination of these indicators can improve the credibility of the results. It is not the simple linear relationship between their concentration and the level of chromate exposure. It is only when the level of CrB is below 9.10 and 10.50 μg/L that the MN frequency and urinary 8-OHdG can, respectively, show the degree of genetic damage quantitatively.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: PL together with YG conceived and executed the investigation, analysed the data and described the manuscript. YL and JY supported this investigation from the epidemiological aspect. GJ is responsible for the whole conduct of this study and all of its contents. SY contributed to the organisation and arrangement of the scene investigation. All authors commented critically on the manuscript and agree with the final version submitted.

Funding: This work was supported by the project of National Natural Science Foundation of China (81073043 and 81072281) and the Doctor Fund of Ministry of Education of China (20120001110103).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This research was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Peking University, Health Science Center (HSC), Beijing, China.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Monika G, Joachim E, Peter B, et al. Biological effect markers in exhaled breath condensate and biomonitoring in welders: impact of smoking and protection equipment. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2010;83:803–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrea C, Matteo G, Olga A, et al. The effect of inhaled chromium on different exhaled breath condensate biomarkers among chrome-plating workers. Environ Health Perspect 2006;114:542–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shrivastava R, Upreti RK, Seth PK, et al. Effects of chromium on the immune system. Immunol Med Microbiol 2002;34:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shashwat K, Awasthi SK, Srivastava JK. Effect of chromium on the level of IL-12 and IFN-γ in occupationally exposed workers. Sci Total Environ 2009;407:1868–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohammad BH, Marie V, Gabriela C, et al. Low level environmental cadmium exposure is associated with DNA hypomethylation in argentinean women. Environ Health Perspect 2012;120:879––84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiaohua L, Yanshuang S, Li W, et al. Evaluation of the correction between genetic damage and occupational chromate exposure through BMMN frequenciess. J Occup Environ Med 2012;54:166–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Flora S, Bagnasco M, Serra D, et al. Genotoxicity of chromium compounds: a review. Mutat Res 1990;238:99–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu LL, Chiou CC, Chang PY, et al. Urinary 8-OHdG: a marker of oxidative stress to DNA and a risk factor for cancer, atherosclerosis and diabetics. Clin Chim Acta 2004;339:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ren C, Fang S, Wright RO, et al. Urinary 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine as a biomarker of oxidative DNA damage induced by ambient pollution in the Normative Aging Study. Occup Environ Med 2011;68:562–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin CY, Lee HL, Chen YC, et al. Positive association between urinary levels of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine and the acrylamide metabolite N-acetyl-S-(propionamide)-cysteine in adolescents and young adults. J Hazard Mater 2013;261:372–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JY, Mukherjee S, Ngo LC, et al. Urinary 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine as a biomarker of oxidative DNA damage in workers exposed to fine particulates. Environ Health Perspect 2004;112:666–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valavanidis A, Loridas S, Vlahogianni T, et al. Influence of ozone on traffic-related particulate matter on the generation of hydroxyl radicals through a heterogeneous synergistic effect. J Hazard Mater 2009;162:886–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valavanidis A, Vlachogianni T, Fiotakis C. 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG): a critical biomarker of oxidative stress and carcinogenesis. J Environ Sci Health C 2009;27:120–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenech M, Kirsch-Volders M, Natarajan AT, et al. Molecular mechanisms of micronucleus, nucleoplasmic bridge and nuclear bud formation in mammalian and human cells. Mutagenesis 2011;26:125–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sobol Z, Schiestl RH. Intracellular and extracellular factors influencing Cr (VI) and Cr (III) genotoxicity. Environ Mol Mutagen 2012;53:94–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuo H, Chang S, Wu K, et al. Chromium (VI) induced oxidative damage to DNA: increase of urinary 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine concentrations (8-OHdG) among electroplating workers. Occup Environ Med 2003;60:590–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim H, Cho S-H, Chung M-H. Exposure to hexavalent chromium does not increase 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine levels in Korean chromate pigment workers. Ind Health 1999;37:335–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao M, Levy LS, Faux SP, et al. Use of molecular epidemiological techniques in a pilot study on workers exposed to chromium. Occup Environ Med 1994;51:663–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang XH, Zhang X, Wang XC, et al. Chronic occupational exposure to hexavalent chromium causes DNA damage in electroplating workers. BMC Public Health 2011;11:224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiaohua L, Yanshuang S, Li W, et al. Evaluation of the correction between genetic damage and occupational chromate exposure through BMMN frequencies. J Occup Environ Med 2012;54:166–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danadevi K, Rozati R, Banu BS, et al. Genotoxic evaluation of welders occupationally exposed to chromium and nickel using the Comet and micronucleus assays. Mutagenesis 2004;19:35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson CM, Fedorov Y, Brown DD, et al. Assessment of Cr (VI)-induced cytotoxicity and genotoxicity using high content analysis. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e42720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.GBZ 159–2004. Specifications of air sampling for hazardous substances monitoring in the workplace, China: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song Y, Zhang J, Yu S, et al. Effects of chronic chromium (VI) exposure on blood element homeostasis: an epidemiological study. Metallomics 2012;4:463–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fenech M. Cytokinesis-block micronucleus cytome assay. Nat Protoc 2007;2:1084–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clancy HA, Sun H, Passantino L, et al. Gene expression changes in human lung cells exposed to arsenic, chromium, nickel or vanadium indicate the first steps in cancer. Metallomics 2012;4:784–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chhabra D, Oda K, Jagannath P, et al. Chronic heavy metal exposure and glbladder cancer risk in India, a comparative study with Japan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012;13:187–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan L, Jia G, Zhang J, et al. The correlation between personal occupational exposure to soluble chromate and urinary chromium content. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2006;40:386–9 (article in Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ding CG, Pan Yj, Zhang AH, et al. Distribution of chromium in whole blood and urine among general population in China between year 2009 and 2010. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2012;46:679–82 (article in Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhitkovich A. Importance of chromium-DNA adducts in mutagenicity and toxicity of chromium(VI). Chem Res Toxicol 2005;18:3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang TC, Song YS, Wang H, et al. Oxidative DNA damage and global DNA hypomethylation are related to folate deficiency in chromate manufacturing workers. J Hazard Mater 2012;213.214:440–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brien TJ, Ceryak S, Patierno SR. Complexities of chromium carcinogenesis: role of cellular response, repair and recovery mechanisms. Mutat Res Fundam Mol Mech Mutagen 2003;533:3–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martini CN, Brandani JN, Gabrielli M, et al. Effect of hexavalent chromium on proliferation and differentiation to adipocytes of 3T3-L1 fibroblasts. Toxicol In Vitro 2014;28:700–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goulart M, Batoreu M, Rodrigues A, et al. Lipoperoxidation products and thiol antioxidants in chromium exposed workers. Mutagenesis 2005;20:311–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan FH, Ambreen K, Fatima G, et al. Assessment of health risks with reference to oxidative stress and DNA damage in chromium exposed population. Sci Total Environ 2012;430:68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sumner ER, Shanmuganathan A, Sideri TC, et al. Oxidative protein damage causes chromium toxicity in yeast. Microbiology 2005;151:1939–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steenken S, Jovanovic SV, Bietti M, et al. The trap depth (in DNA) of 8-oxo-7, 8-dihydro-2′ deoxyguanosine as derived from electron-transfer equilibria in aqueous solution. J Am Chem Soc 2000;122:2373–4 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang T, Jia G, Zhang J, et al. Renal impairment caused by chronic occupational chromate exposure. Int Arch Occ Env Hea 2011;84:393–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Urbano AM, Ferreira LM, Alpoim MC. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of hexavalent chromium-induced lung cancer: an updated perspective. Curr Drug Metab 2012;13:284–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Lemos CT, Rödel PM, Terra NR, et al. Evaluation of basal micronucleus frequency and hexavalent chromium effects in fish erythrocytes. Environ Toxicol Chem 2001;20:1320–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reynolds M, Armknecht S, Johnston T, et al. Undetectable role of oxidative DNA damage in cell cycle, cytotoxic and clastogenic effects of Cr(VI) in human lung cells with restored ascorbate levels. Mutagenesis 2012;27:437–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bagchi D, Stohs SJ, Downs BW, et al. Cytotoxicity and oxidative mechanisms of different forms of chromium. Toxicology 2002;180:5–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fenech M, Holland N, Zeiger E, et al. The HUMN and HUMNxL international collaboration projects on human micronucleus assays in lymphocytes and buccal cells—past, present and future. Mutagenesis 2011;10:239–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonassi S, Fenech M, Lando C, et al. Human MicroNucleus Project: International database Comparison for results with the cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay in human lymphocytes: effect of laboratory protocol, scoring criteria, and host factors on the frequency of micronuclei. Environ Mol Mutagen 2001;37:31–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vasylkiv OY, Kubrak OI, Storey KB, et al. Cytotoxicity of chromium ions may be connected with induction of oxidative stress. Chemosphere 2010;80:1044–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arakawa H, Tang MS. Recognition and incision of Cr(III) ligand-conjugated DNA adducts by the nucleotide excision repair proteins UvrABC: importance of the Cr(III)-purine moiety in the enzymatic reaction. Chem Res Toxicol 2008;21:1284–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.