Abstract

Introduction

Low levels of health-enhancing physical activity require novel approaches that have the potential to reach broad populations. Web-based interventions are a popular approach for behaviour change given their wide reach and accessibility. However, challenges with participant engagement and retention reduce the long-term maintenance of behaviour change. Web 2.0 features present a new and innovative online environment supporting greater interactivity, with the potential to increase engagement and retention. In order to understand the applicability of these innovative interventions for the broader population, ‘real-world’ interventions implemented under ‘everyday conditions’ are required. The aim of this study is to investigate the difference in physical activity behaviour between individuals using a traditional Web 1.0 website with those using a novel Web 2.0 website.

Methods and analysis

In this study we will aim to recruit 2894 participants. Participants will be recruited from individuals who register with a pre-existing health promotion website that currently provides Web 1.0 features (http://www.10000steps.org.au). Eligible participants who provide informed consent will be randomly assigned to one of the two trial conditions: the pre-existing 10 000 Steps website (with Web 1.0 features) or the newly developed WALK 2.0 website (with Web 2.0 features). Primary and secondary outcome measures will be assessed by self-report at baseline, 3 months and 12 months, and include: physical activity behaviour, height and weight, Internet self-efficacy, website usability, website usage and quality of life.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has received ethics approval from the University of Western Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference Number H8767) and has been funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (Reference Number 589903). Study findings will be disseminated widely through peer-reviewed publications, academic conferences and local community-based presentations.

Trial registration number

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry Number: ACTRN12611000253909, WHO Universal Trial Number: U111-1119-1755

Keywords: PREVENTIVE MEDICINE, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is both novel and necessary as it examines the dissemination of a ‘real-world’ trial, in a natural setting, consisting of ‘everyday’ challenges that are not necessarily apparent in a randomised controlled trail.

This intervention has a wide reach with the potential for it to be extended to broad, diverse populations throughout Australia and internationally.

This study will identify the successful components and challenges associated with Web-based health promotion interventions, particularly concerning engagement and retention.

Given the real world dissemination and wide reach of this intervention, we are limited in collecting objectively measured physical activity data, thus relying on self-reported measures alone.

Introduction

Regular physical activity (PA) plays an integral role in health promotion and disease prevention.1 In addition to decreasing the risk of premature mortality, PA also reduces the risk of developing chronic disease, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, some cancers, obesity, osteoporosis/osteoarthritis and poor mental health.2–4 Despite the numerous physical and mental health benefits associated with PA, nearly 45% of adults (15 years or older) from Western countries do not engage in enough PA to confer health benefits.5 In Australia alone, 60% of adults (15 years or older) are not meeting minimum PA recommendations of 150 min of moderate-vigorous PA per week.6 It is estimated that these low levels of PA contribute to more than 8000 deaths in Australia each year, and that for every 1% of the Australian population that becomes sufficiently physically active some $7.2 million in healthcare costs could be saved annually.7 Motivating the population to attain higher levels of PA has been difficult, which emphasises the need for novel approaches that have the potential to reach broad populations.

One particular approach that has become increasingly popular within PA research is the use of the Internet to deliver health promotion and PA behaviour-change interventions. Given the unprecedented growth in Internet usage worldwide8 and across many populations, including women, elderly and those of low socioeconomic status,9–11 it is not surprising that the Internet provides an attractive medium that has the potential to reach large diverse populations, providing greater accessibility to health promotion and behaviour change approaches. A number of literature reviews have demonstrated the effectiveness of Internet-based PA interventions for behaviour change, highlighting positive short-term behaviour change outcomes.12–14 Few studies, however, have reported long-term behaviour change, or have examined the effectiveness of specific website components that may impact short-term and/or long-term behaviour change. The lack of maintenance of behaviour change has often been attributed to low levels of participant engagement and retention, and requires innovative approaches to address this challenge.13 15 16

Web 2.0 features may be a promising approach to increasing user interaction and retention. Web 2.0 refers to a second generation of Internet-based features that are recognised to be highly interactive, and that have evolved from the traditional ‘read only’ website features to more participatory features, providing users with personal influence of how information is generated, created and shared collaboratively.17 18 Such features might include a wide range of interactive features such as blogs, wikis, podcasts, mash-ups and social networking, all of which have the potential to revolutionise website usage if utilised effectively.19 Further, there is growing acknowledgement that Web 2.0 features show promise in the field of health promotion and healthcare.19–22 In order to fully understand the true effectiveness of Web 2.0 technologies in ‘real-world’ health promotion and healthcare practice, there is a need for large scale population-based studies that are evaluated in real-world settings.

In the past, PA intervention and behaviour change research has focused on the evaluation and outcomes of efficacy, in which efficacy of intervention is defined as its effect under ‘ideal conditions’.23 These ‘ideal conditions’ commonly consist of tightly controlled, short-term randomised control trials (RCT) which are utilised in an effort to increase the internal validity of the intervention design.24 Although RCTs are often considered the gold standard of trial design due to their ability to minimise the impact of selection and information biases, control for confounding variables and potentially rule out chance, they have often been challenged on the grounds of external validity.23–26 Moreover, these types of interventions can be nearly impossible to adopt or implement in real-world settings, where participants are more likely to have a variety of health issues, numerous unforeseen external influences, and are often less motivated to engage in PA.24 27 28 As a result, there is a push to go beyond the use of RCTs alone, specifically in terms of public health and health promotion practice.24 RCT's are an essential component of the research process, as a methodologically sound design will maximise internal validity, as well as provide a measure of efficacy. However, in order to understand effectiveness, generalisability and the true impact of large-scale public health and health promotion interventions on the general population, complementary approaches that go beyond RCTs and that are evaluated under normal, everyday conditions in a real-world setting (or as close to this as possible) are needed.24 27–29 This is particularly relevant to Web 2.0 features, as their spontaneous, viral and often uncontrollable nature makes it difficult to study their true dynamics in controlled RCT circumstances.30 For example, if one cannot invite friends to join a social network, due to RCT-related restrictions, the social network is unlikely to be as functional and effective as it would be in real-world circumstances where such artificial barriers are not present. Therefore, given the proliferation of Web 2.0 features on the Internet, understanding the translation of Web-based PA intervention research into the real-world is becoming increasingly important.31 32

The over-arching aim of the present study is to investigate the difference in PA behaviour between individuals using a traditional Web 1.0 website with those using a novel Web 2.0 website. Second, this study will investigate the effectiveness of Web 2.0 features (eg, involving social networking) to engage and retain individuals to a PA promotion website, as well as examine differences in quality of life between the intervention groups. A two-group randomised trial will be applied to compare a website using the novel Web 2.0 features with a traditional Web 1.0 intervention, and investigate the effectiveness of both interventions in a ‘real-world’ setting. The efficacy and internal validity of the interventions described in this study is also being investigated in a separate RCT, which has been described elsewhere.33

Primary hypothesis

H1: Participants in the Web 2.0 condition will display significantly higher levels of PA at 3 months and 12 months, when compared with the Web 1.0 condition.

Secondary hypotheses

H2: There will be significantly higher retention and engagement in the Web 2.0 condition at 3 months and 12 months, when compared with the Web 1.0 condition, measured using website statistics and a usability survey.

H3: Participants in the Web 2.0 condition will display significantly higher improvements in quality of life at 3 months and 12 months, when compared with the Web 1.0 condition.

Methods

Trial design

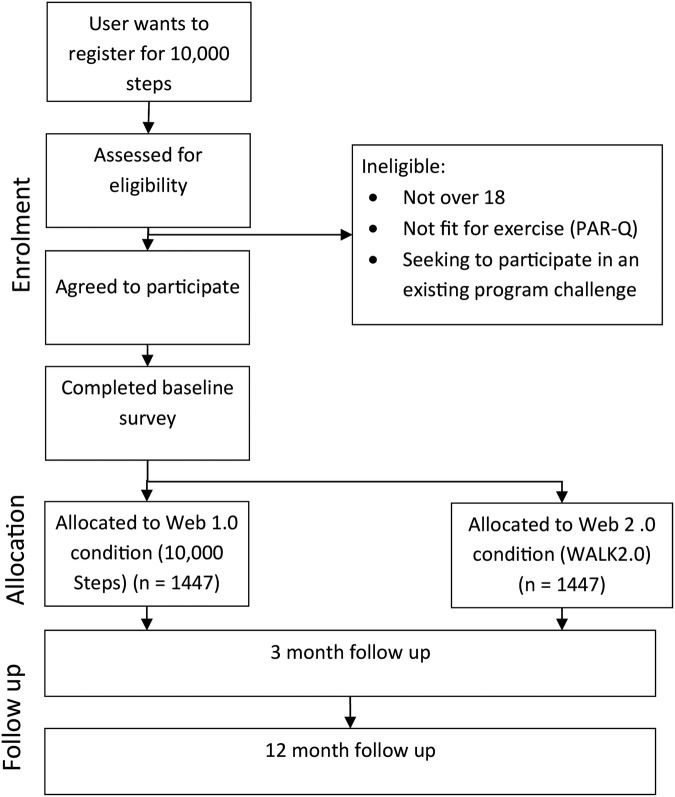

This is the second phase of the larger WALK 2.0 project and aims to build on the earlier RCT33 by investigating the comparative effectiveness of two web-based PA interventions in a real-world setting (figure 1). Participants will be randomly assigned to one of the two interventions, a Web 1.0 condition and a Web 2.0 condition. Outcomes will be assessed at baseline, and at 3 and 12 months. The study will be reported according to CONSORT guidelines.34

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study protocol.

Participants, recruitment and eligibility

The study aims to recruit 2894 participants (approximately 1447 participants per condition) from self-selected new registrants to the existing and freely available 10 000 Steps website. This website is a key component of the 10 000 Steps Australia project, which is a community-level PA promotion project originally started in 2001.35 36 The 10 000 Steps website is used to promote PA through the use of Web 1.0 features, with several interactive features, such as ‘i-challenges’, ‘workplace challenges’, ‘virtual journeys’ and ‘step logs’. Over the past 13 years, the 10 000 Steps website has attracted over 260 000 registered members, an average of 2184 new registrants per month. Further details regarding the 10 000 Steps website are described elsewhere.33 37 All adults (18 years of age and older) who seek to register on http://www.10000Steps.org.au of their own impetus will be offered the opportunity to participate in the current study. Participants will be excluded from the current study if they: (1) are under 18; (2) are seeking to participate in a 10 000 Steps workplace challenge38; (3) are, or have been, a participant of the WALK 2.0 RCT33; and (4) have an existing medical condition which could be exacerbated through increasing PA assessed using the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire, (PAR-Q).39

Study procedure

All new users who register with the 10 000 Steps website will be invited to participate in this trial. They will be provided with a brief overview of the project and interested users will then be screened for eligibility using a self-administered online survey, while non-interested users will be returned to 10 000 Steps, as they had initially intended. All interested individuals who meet inclusion criteria will then be invited to provide informed consent. On providing informed consent, all eligible participants will automatically be uniformly randomly assigned to one of the two trial conditions using a computer-generated algorithm. Participants will gain access to the respective intervention websites and will be prompted to complete a brief online baseline survey. All these steps are fully automated, and there will be no interaction with the research team at any point. Participants randomised to the Web 1.0 condition will gain access to the original 10 000 Steps website (http://www.10000steps.org.au), which features Web 1.0 technologies. Participants randomised to the Web 2.0 condition will be assigned to a newly developed website featuring Web 2.0 technologies (http://www.walk.org.au).

Primary and secondary outcome measurements will be assessed by online self-report questionnaires at baseline, 3 and 12 months. These measures will include PA behaviour, height and weight (to calculate the body mass index), Internet self-efficacy, website usability (only assessed at 3-month and 12-month follow-up periods), and quality of life. Website usage statistics will be collected throughout for the entire duration of the study. Demographic data will also be collected at baseline. Participants will receive email invitations to complete the online baseline and follow-up outcome measurements. Participants who have not completed the survey after a 3 week period will be sent a total of three reminder emails (sent 1 week apart) encouraging them to complete the online assessments.

Interventions

Web 1.0 condition

Participants allocated in the Web 1.0 condition will be given access to the existing 10 000 Steps website, using Web 1.0 features. This website was originally developed to promote the community-based 10 000 Steps Australia project36 and includes features that support individual self-monitoring (eg, step log), communication exchange (eg, discussion forums) and access to information and educational resources (eg, benefits of PA). Participants allocated to this condition will be able to log their daily activities, in terms of type and duration of activity and/or number of steps as well as access the website library for information concerning PA and other health behaviours. Participants will also have the opportunity to share stories, ask questions or make comments in the discussion forum. This is a public forum in which all information posted can be viewed by all participants on the website. The Web 1.0 condition does not have the functionality of individualised personal pages or forums.

Web 2.0 condition

Participants allocated to the Web 2.0 condition will be given access to a newly developed website that will provide content and basic functionality similar to the Web 1.0 condition (step log and library), but will be supplemented with Web 2.0 features. These features include annotation, messaging and group publishing tools implemented in a configurable social networking setting where individual user environments may be different. Participants in the Web 2.0 condition will still have access to self-monitoring features and information and educational resources, however, these will have advanced functionalities (eg, status updates, internal emails, requesting ‘friends’, personalised profile pages) providing opportunities for greater interactivity and participatory communication between users. With respect to the personalised profile pages, participants will have the opportunity to add and/or upload content to their own page, share their information with others, invite outside individuals who are not part of the trial to become their friend and use the website (these individuals will be able to use the website, but will not be involved any aspect of the research trial) and access their ‘friends’ profile pages.

Participants of both conditions will not receive any instruction from the research team on the use of the features of the intervention to which they have been assigned, on the basis the website tools provided are not complex or exceptional by comparison with other widely known websites such as Facebook.

Measures

Physical activity

PA will be evaluated through self-report, using the Active Australia Survey.40 The Active Australia Survey evaluates frequency (number of sessions) and duration (hours and/or minutes) of walking for transport and recreation and participation in other moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity PAs during the previous week. The Active Australia Survey has established acceptable test–retest reliability and validity in the Australian adult population, and has been documented as a useful evaluation tool for detecting intervention-related change in PA behaviours.41–43 The Active Australia Survey will be used to determine: (1) sufficient PA (150 min of moderate to vigorous PA per week), (2) total minutes of PA per week, and (3) total sessions of PA per week. Total PA time will be calculated as the sum of time spent walking (if continuous and ≥10 min), the time spent doing moderate level PA, plus double the time spent engaging in vigorous PA, which accounts for the higher volume of energy expenditure per unit time that is associated with vigorous PA.40

Anthropometric measurements

Participants will be requested to provide self-reported measurements of height (in centimeters) and weight (in kilograms). BMI will be calculated from these measurements. Participants will receive information to assist them to convert imperial measurements to metric, but will not be provided with instructions on how to measure their height and weight.

Other measures

Website engagement and retention will be assessed using various website statistics, self-reported internet self-efficacy and website usability. Website statistics will be collected via Google analytics, a commonly available web traffic analysis tool, and the website databases (10 000 Steps, Walk 2.0). Google analytics allows extracting of group-level and individual-level data on a wide range of variables. Specific to this trial, Google analytics will be used to extract information concerning the number of visits to both websites over time (Web 1.0 and Web 2.0), the number of pages accessed for each website per visit, and the time spent on the website for each visit. In addition to the data extracted from Google analytics, specific information will also be extracted from the database of the intervention websites. Data concerning the number of days with a step entry, number of steps logged, and number of friends/walking buddies will be extracted from both the Web 1.0 and Web 2.0 conditions. Additionally, data concerning the number of step entries with a comment, number of stream posts (ie, status updates), number of comments on friends’ streams, number of goals set (by goal type-daily, weekly, etc) and the number of blog entries will be extracted from the Web 2.0 condition.

Internet self-efficacy will be assessed using the Internet Self-Efficacy Scale (ISES), which has previously shown good reliability and internal consistency.44 The ISES is an 8-item survey instrument used to assess participants’ confidence in their ability to execute Internet tasks, gather information and troubleshoot problems with the Internet. A 7-point Likert scale is used to assess participant responses, in which a 7 corresponds with ‘strongly agree’ and a 1 corresponds with ‘strongly disagree’. Website usability will be explored using the System Usability Scale (SUS).45 The SUS is a brief survey tool used to access participant usability of a range of interface technologies. It is a 10-item scale, scored on a 5-point scale of strength of agreement. Final scores can range from 0 to 100, where higher scores indicate better usability.45 The SUS is a highly robust and versatile tool for accessing usability, reporting good reliability and concurrent validity.46

Lastly, the RAND 36 Short Form Health Survey (RAND-36) will be used to assess quality of life.47 48 This instrument measures quality of life via 8 health-related concepts, including physical functioning, bodily pain, role limitations due to physical health problems, role limitations due to personal or emotional problems, emotional well-being, social functioning, energy/fatigue and general health perceptions. RAND 36 was developed from the original SF-36 Medical Outcomes Study Survey.48 Researchers from the original Medical Outcomes Study-MOS49 released a commercial version of SF-36 while the original RAND-36 has been made available license-free from the RAND Corporation. Both survey instruments contain the same items developed for MOS,49 however the scoring for the body pain and general health sections are slightly different between the RAND and SF-36.48 In scoring RAND 36, precoded numeric values are given to each scale item. All items are then scored on a 0 to 100 range, with a high score representing a more favourable health state. Additionally, items in the same scale are averaged together to create 8 scale scores. Any items left blank are referred to as missing data and are not taken into account when calculating the scale scores.48 The RAND 36 has been validated in Australian populations,50 has demonstrated suitability for use in the general population,51 52 and has been associated with the stage of motivational readiness to changes in PA.53 54 All outcome measures are detailed below and in table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of outcome measures

| Data collection instrument | Collection points (months) | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome measures | ||

| Physical activity levels | Active Australia Survey40 | 0, 3 and 12 |

| Secondary outcome measures | ||

| Self-reported anthropometric measurements | Height | 0, 3 and 12 |

| Weight | 0, 3 and 12 | |

| Other measures | ||

| User engagement and retention | Internet self-efficacy scale44 | 0 (Baseline only) |

| System usability scale45 | 3 and 12 | |

| Self-reported quality of life | RAND-3649 | 0, 3 and 12 |

| Descriptive information | Demographics questionnaire | 0 (Baseline only) |

| Website usage | Google analytics Website database | 3 and 12 3 and 12 |

Statistical power and sample size

This trial is powered to detect a 4% difference in the prevalence of sufficient PA as defined by National Physical Activity Guidelines between the Web 1.0 and Web 2.0 groups. To achieve this aim with an 80% power with an α level of 0.05, a minimum of 1034 participants per group will be required.55 A review of web-based PA interventions suggests that studies that do not include aspects of Web 2.0 had a small effect on change in PA status of participants, and had a dropout rate of approximately 30%.16 However, given that this study is not a RCT and that there is no contact with participants whatsoever, the number of participants per group has been inflated by 40% to account for the effects of participant drop-out. Across the intervention period, the study will aim to recruit 1447 participants per group, resulting in a total of 2894 participants recruited into the study.

Statistical analysis

All analyses will follow ‘intention to treat’ principles. Main comparisons between groups will be performed using general linear mixed modelling. The impact of missing data will be addressed using multiple imputation. The sample size is inflated to take into account the possible uncertainty arising from data that is not missing at random. All analyses will be conducted using SPSS for Windows (V.20.0). The level of significance (α) will be set at 0.05.

Discussion

Going beyond a traditional efficacy RCT33 and implementing this intervention to a larger audience, in ‘real-world’ conditions is both novel and necessary. It is beyond any doubt that implementing and evaluating RCTs is still very much warranted, as the outcomes of these tightly controlled studies provide valuable information concerning efficacy and internal validity.24 26 56 However, in relation to population-based interventions that are expected to reach a large proportion of the population in a real-world setting, RCTs alone are limited in yielding valid and generalisable evidence.24 By extending our intervention implementation to a ‘real-world’ trial, we are able to gain a greater understanding of the true effectiveness of an intervention in a natural setting which may be influenced by natural external variables that are not necessarily apparent in a RCT. Variables related to health status, motivation, compliance and resources associated with long-term sustainability are just a few of the external variables not taken into account when carrying out a RCT.23 Being aware of these variables and any other challenges (that may occur due to chance) in a real-world setting, provides us with the opportunity to address them and develop alternative best practice approaches that are logical, plausible and meet the needs of the larger population. The current study provides an opportunity to do this. This real-world trial will provide us with a greater understanding of how to engage and retain participants from the general population, under everyday conditions, in web-based interventions aimed at increasing PA and other health-related behaviours. More importantly, this trial is the first step to understanding the factors associated with population-level dissemination and research translation. Being able to identify the successful components and challenges associated with of Web 2.0 features, particularly concerning engagement and retention, will assist with intervention refinement and further intervention delivery, ultimately impacting PA behaviours and subsequently preventing chronic disease and improving global health.

Footnotes

Contributors: WKM, GSK, AJM, CV, MJD and CMC conceived the project and procured the project funding. GSK is leading the coordination of the trial. GSK, RRR, AJM, CV, MJD, CMC and WKM assisted with protocol design. TNS is managing the trial including data collection with the assistance of AV. AJM and RT developed the IT platform for the trial and MJD performed the sample size calculations. CMC and TNS drafted the manuscript and all authors read, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This trial is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (Project Grant number 589903).

Competing interests: CV was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (#519778) and National Heart Foundation of Australia (#PH 07B 3303) post-doctoral research fellowship during the conception of the research project and recruitment.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval to conduct this trial has been obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Western Sydney (Reference Number H8767).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data, published or unpublished, will only be made available to the research team. All research team members include the authors of this manuscript and potential graduate students or trainees, research coordinators or research assistants, directly related to this project.

References

- 1.WHO. Global health risks: mortality and the burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ 2006;174:801–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Penedo FJ, Dahn JR. Exercise and well-being: a review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2005;18:189–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical activity guidelines for Americans: be active, healthy and happy. Washington, DC: HHS, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, et al. . Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 2012;380:247–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ABS. Australian health survey: physical activity, 2011–2012 Catalogue number 4364.0.55.004. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephenson J, Bauman A, Armstrong T, et al. . The costs of illness attributable to physical inactivity in Australia: a preliminary study. Canberra: The Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care and the Australian Sports Commission, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Internet usage statistics: the big picture. http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm

- 9.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Household use of information technology, Australia, 2010–11. ABS, 2011. [cited 8 Mar 2013]. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/8146.0Contents2010-11?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=8146.0&issue=2010-11&num=&view= [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pink B. Household use of information technology, Australia 2008–09. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Telecommunication Union. Fixed (wired)-broadband subscriptions, 2000–2011 [12 April 2013]. http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/statistics/2012/Fixed_broadband_2000-2011.xls

- 12.Davies CA, Spence JC, Vandelanotte C, et al. . Meta-analysis of internet-delivered interventions to increase physical activity levels. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012;9:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van den Berg MH, Schoones JW, Vliet Vlieland TP. Internet-based physical activity interventions: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res 2007;9:e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelders SM, Van Gemert-Pijnen JE, Werkman A, et al. . Effectiveness of a Web-based intervention aimed at healthy dietary and physical activity behavior: a randomized controlled trial about users and usage. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcus BH, Ciccolo JT, Sciamanna CN. Using electronic/computer interventions to promote physical activity. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:102–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vandelanotte C, Spathonis KM, Eakin EG, et al. . Website-delivered physical activity interventions a review of the literature. Am J Prev Med 2007;33:54–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duffy P. Engaging the YouTube Google-eyed generation: strategies for using Web 2.0 in teaching and learning. Electron J e-Learning 2008;6:119–30 [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Reilly T.2005. What is Web 2.0: Design patterns and business models for the next generation of software. http://www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/news/2005/09/30/what-is-web-20.html.

- 19.Hall AK, Stellefson M, Bernhardt JM. Healthy Aging 2.0: the potential of new media and technology. Prev Chronic Dis 2012;9:E67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doherty I. Web 2.0: a movement within the health community. Health Care Inform Rev Online 2008;12:49–57 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thackeray R, Neiger BL, Hanson CL, et al. Enhancing promotional strategies within social marketing programs: use of Web 2.0 social media. Health Promot Pract 2008;9:338–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metzger MJ, Flanagin AJ. Using Web 2.0 technologies to enhance evidence-based medical information. J Health Commun 2011;16(Suppl 1):45–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Courneya KS. Efficacy, effectiveness, and behavior change trials in exercise research. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2010;7:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Victora CG, Habicht JP, Bryce J. Evidence-based public health: moving beyond randomized trials. Am J Public Health 2004;94:400–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Black N. Evidence based policy: proceed with care. BMJ 2001;323:275–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet 2001;357:1191–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goode AD, Owen N, Reeves MM, et al. . Translation from research to practice: community dissemination of a telephone-delivered physical activity and dietary behavior change intervention. Am J Health Promot 2012;26:253–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antikainen I, Ellis R. A RE-AIM evaluation of theory-based physical activity interventions. J Sport Exerc Psychol 2011;33:198–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilcox S, Dowda M, Leviton LC, et al. Active for life: final results from the translation of two physical activity programs. Am J Prev Med 2008;35:340–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maher CA, Lewis LK, Ferrar K, et al. . Are health behavior change interventions that use online social networks effective? A systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bredin SS, Warburton DE. Physical activity line: effective knowledge translation of evidence-based best practice in the real-world setting. Can Fam Physician 2013;59:967–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spittaels H, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Brug J, et al. Effectiveness of an online computer-tailored physical activity intervention in a real-life setting. Health Educ Res 2007;22:385–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolt GS, Rosenkranz RR, Savage TN, et al. WALK 2.0 Study Protocol: using Web 2.0 applications to promote health-related physical activity—a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2013;13:436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:698–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown WJ, Mummery WK, Eakin E, et al. 10,000 Steps Rockhampton: evaluation of a whole community approach to improving population levels of physical activity. J Phys Act Health 2006;3:1–14 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown W, Eakin E, Mummery WK, et al. 10,000 Steps Rockhampton: establishing a multi-strategy physical activity promotion project in a community. Health Promot J Austr 2003;14:95–100 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davies C, Corry K, Van Itallie A, et al. . Prospective associations between intervention components and website engagement in a publicly available physical activity website: the case of 10,000 steps Australia. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mummery WK, Schofield G, Hinchliffe A, et al. Dissemination of a community-based physical activity project: the case of 10,000 steps. J Sci Med Sport 2006;9:424–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. PAR-Q & you. [cited 2012]. http://www.csep.ca/cmfiles/publications/parq/par-q.pdf

- 40.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The Active Australia Survey: a guide and manual for implementation, analysis and reporting. Canberra: AIHW, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown WJ, Trost SG, Bauman A, et al. Test-retest reliability of four physical activity measures used in population surveys. J Sci Med Sport 2004;7:205–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reeves MM, Marshall AL, Owen N, et al. Measuring physical activity change in broad-reach intervention trials. J Phys Act Health 2010;7:194–202 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown WJ, Bauman A, Chey T, et al. Method: comparison of surveys used to measure physical activity. Aust NZ J Publ Heal 2004;28:128–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eastin MS, LaRose R. Internet self efficacy and the psychology of the digital divide. J Comput Mediat Commun 2000;6 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brooke J. SUS—a quick and dirty usability scale. In: Jordan PW, Thomas B, Weerdmeester BA, McClelland AL, eds. Usability evaluation in industry. 1st edn.London: Taylor and Francis, 1996:194 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewis JR, Sauro J. The factor structure of the system usability scale. In: Kurosu M. ed. Human centered design. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2009:94–103 [Google Scholar]

- 47.VanderZee KI, Sanderman R, Heyink JW, et al. Psychometric qualities of the RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0: a multidimensional measure of general health status. Int J Behav Med 1996;3:104–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM. The RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0. Health Econ 1993;2:217–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCallum J. The SF-36 in an Australian sample: validating a new, generic health status measure. Aust J Public Health 1995;19:160–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stevenson C. SF-36: interim norms for Australian data. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Australian Bureau of Statistics. National health survey: SF-36 population norms; Australia. Canberra: ABS, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laforge RG, Rossi JS, Prochaska JO, et al. Stage of regular exercise and health-related quality of life. Prev Med 1999;28:349–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bize R, Johnson JA, Plotnikoff RC. Physical activity level and health-related quality of life in the general adult population: a systematic review. Prev Med 2007;45:401–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wittes J. Sample size calculations for randomized controlled trials. Epidemiol Rev 2002;24:39–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosen L, Manor O, Engelhard D, et al. In defense of the randomized controlled trial for health promotion research. Am J Public Health 2006;96:1181–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]