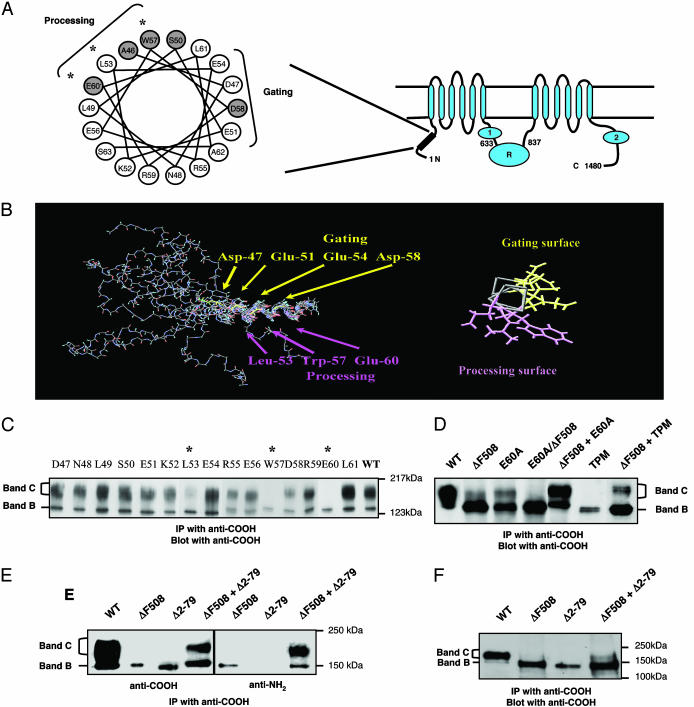

Fig. 1.

Identification of N-tail processing mutants that transcomplement ΔF508-CFTR. (A) CFTR topology showing the two cytoplasmic tails NBD1 and NBD2 and the regulatory (R) domain. (Left) Helical wheel representation of amino acids 46–63 in the N-tail. Amino acids that are sites for CF mutations (www.genet.sickkids.on.ca) are shaded. (B) NMR structure of a synthetic N-tail peptide (amino acids 30–63) depicting an α-helix from residues 47–62. The end-on representation illustrates two distinct surfaces, one implicated in channel gating (18) and the other in CFTR processing (present findings). (C) Single alanine-substituted mutants of CFTR expressed in COS-7 cells. Asterisks indicate processing mutants for which band B (the core-glycosylated form of CFTR) is predominant. CFTR protein was detected 24 h after transfection as described in Methods. (D) Coexpression of ΔF508-CFTR with N-tail processing mutants increased the amount of mature protein (band C). A CFTR polypeptide that harbored two mutations in cis (E60A/ΔF508) exhibited no band C formation. (E) Transcomplementation of ΔF508-CFTR by coexpression with a deletion mutant that lacks the N-tail Δ2–79-CFTR. (F) Coexpression of ΔF508-CFTR and Δ2–79-CFTR led to a modest appearance of band C in human embryonic kidney cells, HEK293T. All results are representative of three to five experiments.