Abstract

Many diseases are related to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hydrodynamics. Therefore, understanding the hydrodynamics of CSF flow and intracranial pressure is helpful for obtaining deeper knowledge of pathological processes and providing better treatments. Furthermore, engineering a reliable computational method is promising approach for fabricating in vitro models which is essential for inventing generic medicines.

A Fluid-Solid Interaction (FSI)model was constructed to simulate CSF flow. An important problem in modeling the CSF flow is the diastolic back flow. In this article, using both rigid and flexible conditions for ventricular system allowed us to evaluate the effect of surrounding brain tissue. Our model assumed an elastic wall for the ventricles and a pulsatile CSF input as its boundary conditions. A comparison of the results and the experimental data was done. The flexible model gave better results because it could reproduce the diastolic back flow mentioned in clinical research studies. The previous rigid models have ignored the brain parenchyma interaction with CSF and so had not reported the back flow during the diastolic time. In this computational fluid dynamic (CFD) analysis, the CSF pressure and flow velocity in different areas were concordant with the experimental data.

Keywords: Cerebrospinal Fluid, FSI modeling, Pulsatile, Hydrodynamics, Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)

1. Introduction

The area around the spinal cord and the brain contains the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) as depicted in Figure 1. From the hydrodynamic point of view, the circulatory dynamics of cerebrospinal fluid and that of cerebral blood within brain tissues give rise to intracranial pressure (ICP) which can in turn be affected by infectious diseases. Since the flow pattern of CSF within the Human Ventricular System (HVS) is complicated due to its complex geometry, investigating the CSF and cerebral blood hemodynamic, by means of HVS modeling or simulation, allows the physician to gather accurate information about CSF dynamics and provides the opportunity to diagnose effective mechanisms of brain diseases and apply appropriate medical or surgical interventions. Furthermore, it will help diagnosis of diseases such as hydrocephalus in more persist and efficient manner. Additionally, recent researches show that the fluid dynamic has significant effect on stem cell differentiation (Benitah, 2012; Patrachari, Podichetty, & Madihally, 2012). As a result, a better understanding of CSF can be promising for studying neurons in their early stages. Having models with consistent similarities with in vivo conditions enhances fabrication of in vitro models which is not only essential for lab studies(Whyte et al., 2012), but also plays an important role in custom designed treatments(Whyte et al., 2012).

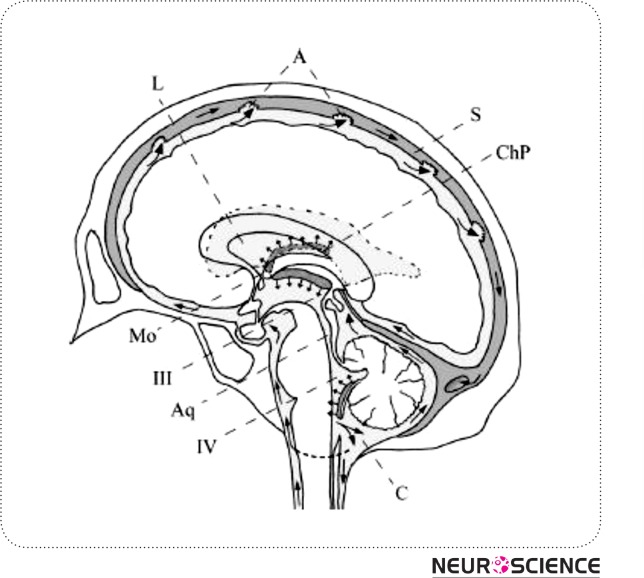

Figure 1.

Schematic median sagittal cut of the human brain displaying CSF circulation. Arrows indicate flow direction. L: lateral ventricles, Mo: foramen of Monro, III: third ventricle, Aq: aqueduct of Sylvius, IV: fourth ventricle, A: arachnoid villi, C: cerebellomedullary cistern, ChP: choroid plexus of lateral ventricles, S: superior sagittal sinus. Based on: Putz/Pabst: Sobotta, Atlas der Anatomie des Menschen, 21th ed. 2000, © Elsevier, Urban & Fischer München

Various mathematical models known as lumped parameter models are in place to help establish the complex situations leading to ICP alterations in people suffering from severe brain diseases(Chopp & Portnoy, 1980; Meier, Zeilinger, & Kintzel, 1999; Ursino, 1988; Ursino & Lodi, 1997). Despite the ability of these models to understand physiology, their complexity and computationally difficulty make it difficult to apply them in clinical settings.

With the great advance of computational capacities and the widespread use of software simulation during the past decade, building real2D,albeit easy, as well as 3D anatomical geometries has increasingly become easy. Moreover, novel models which rely on CFD simulations along with numerical analysis of mechanical structure have been introduced(Jacobson EE, 1996a). Unlike lumped parameter models, the current novelrepresentations give rise to the CSF pressure as well as velocity distribution. For the purpose of capturing the widest probable range of outcomes of the regional-geometry on the way of CSF flow, in vivo brain anatomy information is crucial. Magnetic-resonance-imaging, (MRI) can be used to acquire this information.

We adopted a simplified 2D model to gain insight in to inclusion of a deformable CSF-parenchyma interaction in the model simulation. So far, all of the present models are based on some simple approximations for their boundary conditions or input and output values such as non-pulsatile CSF flow pattern and rigid condition for HVS.

Except Linninger et al. (Ursino, 1988), none of the present models consider the real pulsatile flow pattern and choroid plexus expansion synchronized with the heartbeat, whose importance was described by Davson and Greitz(Ye & Bogaert, 2008). Current models refuse to consider the effect of interaction of the parenchyma with CSF flow, which keeps the simulation away from real nature. Although Cheng et al. (Kaczmarek, Subramaniam, & Neff, 1997) have considered the interaction of surrounding parenchyma as an elastic membrane with different rigidities at different parts, they have not modeled the CSF inflow as a pulsatile current. In their model, the pulsatility of CSF is secondary to pulsatile wall motion which is in contrast with the pulsatile nature of CSF secretion from the choroid plexus (Jones, Newell, Lee, Cripton, & Kwon, 9000). A 2D CFD model of the intracranial-CSF system has been published by Linningeret al. based on pulsatile-CSF production. In their model, CSF flows from rigid HVS towards the porous structure around the HVS (parenchyma). However, the CSF flow enters the parenchyma from the ventricles and from the subarachnoid space (SAS) in some pathological circumstances like hydrocephalus (Greitz, 2004). Cheng (Kaczmarek et al., 1997)has considered an elastic membrane as the CSF parenchyma boundary condition with varying standards of elasticity allocated at a range of regions of the membrane.

In addition, clinical experiments (Ursino, 1988), (Nitz et al., 1992)-(Zhu, Xenos, Linninger, & Penn, 2006) have confirmed the reversal of CSF stream starting from the fourth ventricle back into the3rdventricles during the diastolic time. This is an important incident that has not been observed in previous modeling, except Linninger's model (Ursino, 1988) which was obtained from a pulsatile CSF production. In his work, he considered the minus value while there is always a positive charge of CSF from choroid plexuses. We can assume several hypotheses for CSF diastolic back flow. One is the belief that the pulsatile CSF production stems from arteriolar pulsation in the choroid plexus (Nitz et al., 1992; Ursino, 1988). Another idea is that arteriolar pulsation in the parenchyma causes ventricular wall displacement (Marmarou, Shulman, & Rosende, 1978; Ursino & Lodi, 1997). This in turn, leads to pressure drop in lateral ventricles and pulsatile CSF motion.

In the two hypotheses, the anticipated means of ventricular displacement depends on the arterioles’ pulsation and the interaction between the CSF and the surrounding brain tissue. In the first idea, the arteriolar pulsation has an impact on the CSF generation in choroid plexuses and in the second one it causes ventricular wall pulsation which leads to the CSF pulsatile flow pattern. In this study, we have considered the first approach and we believe that FSI analysis of HVS-CSF boundary yields more realistic results evidenced by Cine-phase MRI (Goldsmith, 2001; Gu et al., 2012; Nitz et al., 1992; Yoo et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2006).

2. Materials

We aim at applying the physical ideology of fluid flow and solid material to computeintracranial CSF hydrodynamics with the interaction of surrounding brain tissue. Three stages are involved in performing the procedure. In the first step, MRI image is applied to accurately define the ventricular geometry of the patient. In step two, the MR image is converted into accurate two-dimensional planar model with CATIA (version 5 R13) software. The accuracy of the model was checked by selection of definite anatomical points in MRI section and obtaining the distances with the help of MRI scanner workstation software and comparing these data with the similar distances between corresponding points in CATIA model. On this basis, mean error estimates in different direction ranged from 1 to 2%. The computational model is imported into Automatic-Dynamic-Incremental-Nonlinear-Analysis, a software abbreviated as ADINA; version 8.2 of the software is considered appropriate. Mesh generation is later applied in partitioning the spaces into a big number of minute finite elements. In the third step, ADINA handles numerically the mathematical equations of the fluid motion based on first principles and constitutive equations over the HVS and brain tissue.

2.1. Geometry of Model

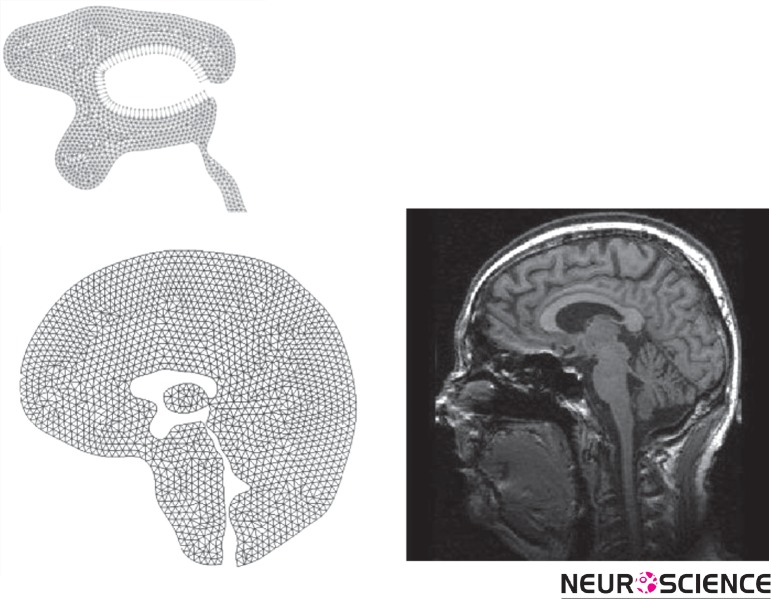

The geometry of the ventricular space of a healthy 21-year-old male volunteer was obtained from the midsagittal images with a 1.5-Tesla MR scanner. Images were acquired using T2WI technique. In this work, for simplicity we did not model the SAS and also the effect of CSF absorption into arachnoids villi was not considered (See Fig. 2a-b).

Figure 2.

(a) Brain tissue geometry with finite-element meshing, (b) Brain MRI scan of the volunteer.

3. Methods

In order to understand the nature of CSF-motion, a computational model to be used to predict the CSF flow pattern in the cranial vault was thus designed. The CSF spaces in the brain were removed from the MR-images. The mathematical model underlies maintenance laws of accumulation and impetus for CSF and constitutive relations for brain tissue.

3.1. Physical Properties of Material

CSF fluid is quite similar to water. Thus it was modeled like a Newtonian solution with constant material properties including the CSF viscosity (µ) and the density (ρ). These values were used both in Rigid and FSI models.

The brain parenchyma has been modeled like a linear stretchy material in FSI model. The essential parameters for this model comprise the Young's modulus (E), the Poisson proportion(v)as well as the solid mass(ρw). These parameters are listed in Table I.

Table 1.

Parameters used for CSF fluid and brain tissue

| Parameters | Value | References |

|---|---|---|

| E Young modulus | 10-30 kPa | [31,34] |

| v Poisson's ratio | 0.49 | [28] |

| µ CSF Viscosity | (Pa.s)0.001003 | [13] |

| P CSF Density | 1000-1007 kg/m3 | [13] |

| [8] | ||

| Pa Brain Tissue Density | Specific gravity: 1.02 | [30] |

3.2. The Equations

Due to the pulsatile flow pattern in the ventricular system, the analysis for solid and fluid considered steadystate dynamics in the results.

3.2.1 Fluid

In both the rigid and the FSI models, the stream is implicit to be laminar, along with CSF is considered Newtonian, viscous and incompressible. The conservation balances result to a structure of biased differential equations referred to as continuity as well as the Navier-Stokes equations. The main equations for CSF-flow are provided in vector type by equations (1) and (2) as shown below:

| 1 |

| 2 |

Where stands for flow velocity, stands for mesh velocity while stands for pressure

3.2.2. Solid

In the FSI model, brain parenchyma is modeled like a linear elastic substance in contact with CSF fluid and for mathematical modeling the Arbitrary-Lagrangian-Eulerian (abbreviated as ALE) formulation is applied to be like the prevailing rule. This leads to equation (3):

| 3 |

Where stands for Cauchy stress tensor, stands for solid-displacement component and ρ s stands for the solid tissue density.

3.2.3. Fluid-Structure Interaction in the FSI Model

Regarding this formulation, the coupling-conditions of the fluid as well as the solid interaction has to be content. The kinetic coupling conditions which denote the no-slip situations at the boundary are:

| 4 |

| 5 |

The kinetic coupling situation denotes the balance of forces as shown below:

| 6 |

Where d is the displacement and σ ij is the stress tensor and the superscript s and f represent the brain tissue and CSF, respectively. Here, n is the unit vector ordinary to the boundary of the solution and solid regions. Equation (6) gives the equilibrium of forces sandwiched between the solution and the solid at the border interface

3.3. Boundary Conditions and Simplified Approximation

The inflow is the CSF production from choroid plexus lateral ventricle and the third ventricles. The outflow is from the Luschka and Magendie foramina and considered to have zero pressure to obtain the pressure distribution. The immense production is as a result of CSF production in the choroid plexus which is a pulsatile generation due to the arterioles pulsation in choroid plexus synchronized with the heartbeat. The rate of recurrence of the pulsatile movement is put to 1 Hz (approximating kin to the usual cardiac cycle) (Sivaloganathan, Tenti, & Drake, 1998). For simplification, we considered a relative pressure (zero value) at the end of Magendie foramina, i.e.,

| 7 |

| 8 |

Where Q is flow rate from choroid plexuses in lateral ventricle and the 3rd ventricle, is the CSF pulsatile generation, s the pressure and is outlet pressures. CSF generation in choroid plexus is as below(Ursino, 1988):

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

Where α represents amplitude of the pulsation and ω is the heart beat rate. The bulk CSF production,, is considered to be 600 ml/day.

In addition, regarding to the two different modeling that we are proposing in our study (rigid wall and deformable wall) for HVS system (FSI) a set of border line circumstances requires to be precise. For solving the problem with rigid condition, the kinematic compatibility declares the non-slip velocity on ventricular wall while for solving the problem with Fluid-Solid interaction in deformable model, both the compatible kinematic and dynamic conditions in solid–fluid boundary should be defined. The kinematic compatibility declares the non-slip velocity on brain tissue in the boundary with skull. The dynamic compatibility described as equilibrium equations on ventricular wall. The two models were compared from a hydrodynamics point of view.

Boundary condition for the rigid model is:

| 12 |

Where is flow velocity on ventricular wall. The fluid wall considered non-slip and no solid were considered around the ventricular wall.

Based on the equations of the Solid-Fluid interaction, below is a set of boundary conditions which will be applied in our model.

Equilibrium equations and boundary conditions for deformable (FSI) model are:

| 13 |

| 14 |

| 15 |

The above equations put into effect that the figures of displacement and that of velocity the two fluids and the solid be the same at the border. In the FSI model, the boundary circumstances for the fluids are: (1) a pulsatile state beside the wall, (2) the outlet pressure is equivalent to zero to obtain a relative distribution of pressure in HVS and (3) FSI condition between the CSF and the surrounding brain parenchyma. Also, the boundary circumstances for the solid domain are: (1) outside of the parenchyma is fixed to the skull, therefore, no displacement is considered for this region and (2) as for the liquid model the FSI circumstances are distinct between the tissue and CSF in the ventricles.

3.4. Simulation Process

The 2D geometry of the patient ventricular system was constructed based on the sagittal section of T2 weighted images of brain MRI for a patient. The JPEG picture were imported to the CATIA software (version: 5R13) to be converted to an analyzable format. The model in IGES format was meshed in ADINA software (version: 8.2). Solid components have been constructed in ADI-NA and the fluid segment in ADINA-F domain.

To inflict the loads, we well thought-out 30 steps of 1s in addition to growing the inlet velocity as well as outlet pressure with a ramp-function. For the purpose of reaching a steady-state resolution with the recognized inlet velocity and, more significantly, the accurate pressure drop, 300 instance steps of 0.001s with the set definitive load are well thought-out.

Newtonian iteration technique and FSI situations are applied in solving the process for deformable model. The restricted element equations for the structure as well as the fluid were handled using the Newton-Raphson iterative-technique. Convergence for solutions is realized when:

| 16 |

where represents the variables to be solved (flow-velocity, pressure along with wall displacement), denotes iteration as well as index is a little number in case is close to zero. TOL is a particular tolerance that is put to have a figure of 0.0005 in the current paper. The figure of iterations is set to 100.

3.4.1. Computational Mesh Generation

Fluid-domain is meshed with 3060 2D Fluid Planar kind elements. All fluid-elements are triangular in shape and have 3 nodes. 3665 2D Solid Plane strain-type elements are applied for the solid areas. All solid-elements are triangular in shape and have 4 nodes. All the elements are first-order-elements. The elements are polished where a composite flow-domain is predictable as revealed in Fig. 2(a). The figures of the elements for the solution and solid-models are established by repeating the result using diverse mesh sizes, and so the best mesh size in which the self-regulating of the solution is availed. The overall result time was approximately 2 hours on a 3.2 GHZ Intel-Pentium-four (4.0 GB-RAM) processor.

4. Results

The outcomes of the CSF-analysis are the flow-rate, velocities, as well as ICP-gradients of CSF in the ventricular-system. In addition, obtaining the lateral ventricular displacement and stress distribution in solid part are the parameters which were calculated in the deformable model.

After solving the model equations within the defined boundary conditions, we first obtained the CSF flow velocity and pressure field inside the cranial vault in the rigid model. In the flexible model, considering FSI condition not only helped us to present the LV displacement and stress distribution in solid part but also led to the observation of additional details in CSF flow pattern such as an upward flow through HVS(Zhu et al., 2006).

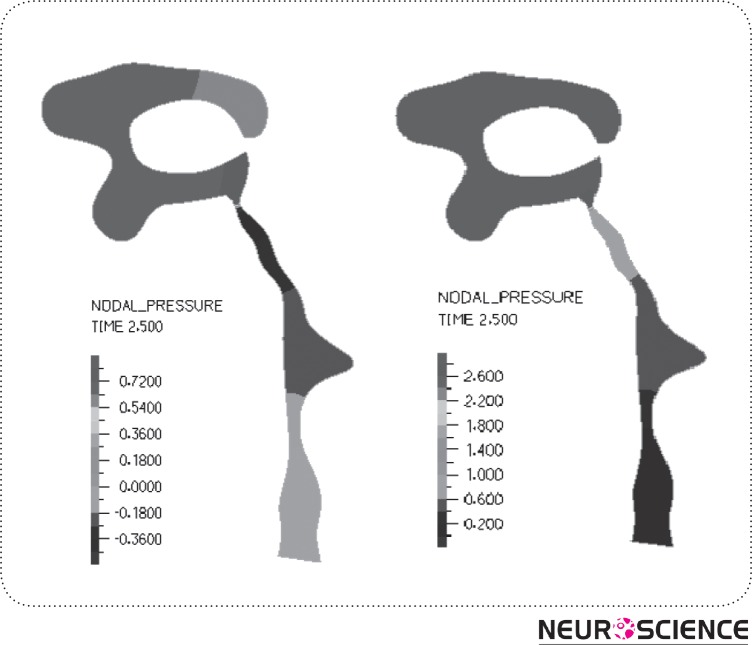

Fig. 3 displays the pressure field, (a) shows the pressure contour for the rigid HVS and (b) for the FSI model. Fig. 4 plots the pre-expected CSF-flow velocity pattern inside the ventricles. As observed in here, there was no significant difference between the two FSI and rigid boundary conditions in terms of velocity profile. Additionally, it is seen that the highest CSF velocity occurs within the cerebral aqueduct. The results of pressure gradient in HVS and velocity magnitude for both conditions are provided in Table II. Comparing the outcomes of rigid and FSI models indicates that velocity magnitude and pressure drop decline up to two times when the tissue interaction is included. Consequently, the pressure drop in HVS of the rigid model declines from 3.5 Pa to 2.4 Pa in FSI model. Also, the maximum velocity magnitude decreases from 11 mm/s in the rigid model to 8 mm/s in the FSI model. Moreover, in the FSI model, we obtained the maximum displacement of 0.09 mm for lateral ventricles. This displacement was responsible for the 1.5%-2.5% LV size change.

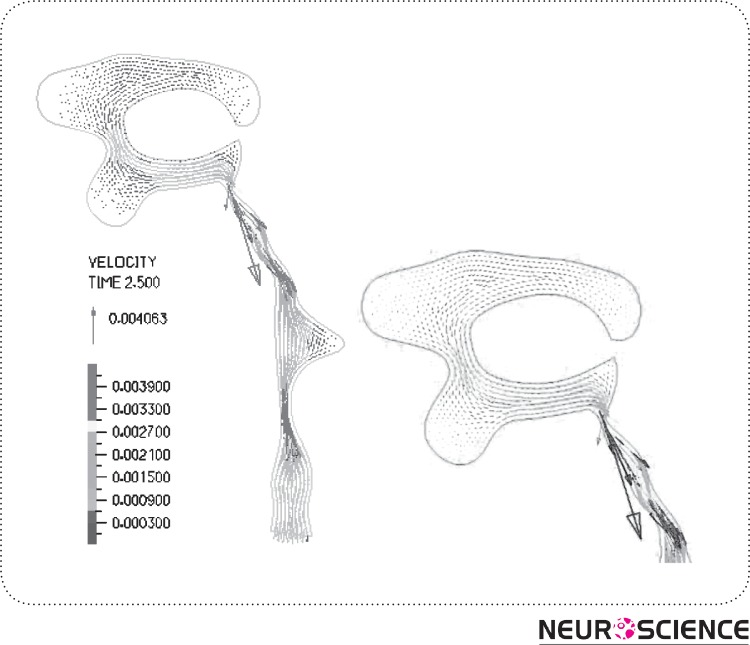

Figure 3.

Pressure distribution in HVS (Pa), (a) in rigid model, (b) in flexible model. As depicted,pressure drop in aqueduct is increased in the flexible model.

Figure 4.

CSF flow and velocity(m/s) vectorsin HVS (in FSI model). The figure shows the flow pattern in lateraland the 3rd ventricles in details.

Table 2.

Results of maximum CSF pressure and velocity in HVS for rigid and flexible models.

| Parameter | Rigid | FSI |

|---|---|---|

| Aqueduct Velocity | mm/s 11 | mm/s8 |

| Magendie Velocity | mm/s5 | mm/s3.2 |

| Monro Velocity | mm/s3.5 | 2 mm/s |

| AS (Aqueduct Sylvian) Pressure Drop | Pa 2.1 | Pa1.3 |

| Total Pressure Drop | 3.5 Pa | -0.2 - 2.4Pa |

| Ventricular Expansion | - | 1.5-2.5% |

As listed in Table III, the maximum values of CSF-velocity plus pressure drop occur in the aqueduct. In the FSI model, the maximum CSF velocity is in aqueduct region, reported as -6 in diastolic time to +8 mm/s in systolic time. Also, the pressure drop along this region went up to 1.5 Pa during systole. Fig. 5 shows the pressure distribution in different times of a cardiac cycle in HVS in the FSI model. It is observed that the pressure drop varies from -0.2 Pa in diastole to 2.4 Pa in systole in HVS.

Table 3.

Comparison of the results of FSI model and MRI experiments.

| Parameter | FSI | MRI Reports |

|---|---|---|

| Aqueduct velocity | mm/s-6/+8 | 3.7 [26] |

| Avg, 2 mm/s [26] | ||

| -7/+6 mm/s [17] | ||

| Magendie velocity | mm/s3.2 | 2.4-5.6mm/s [21] |

| Monro velocity | 2 mm/s | 1-3 mm/s [21] |

| AS pressure drop | Pa1.3 | 0.029 mmHg(3.8 Pa) [22] |

| Total pressure drop | -0.2 - | 5-20Pa [13] |

| 2.4Pa | ||

| Ventricular expansion | 1.5-2.5% | 5-20% [28] |

| 2-5% [23] |

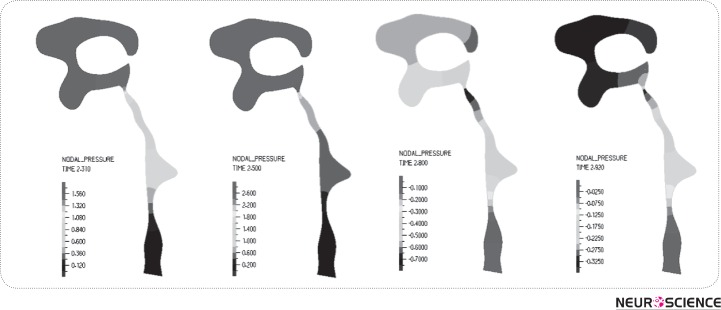

Figure 5.

Pressure distribution during a cardiac cycle; (a) Early systole, (b) Mid systole, (c) Late systole, (d) Diastole. The results show that the maximum pressure drop in HVS occurs in mid systole. Negativeamounts for pressure drop in diastol account for the back flow in diastole.

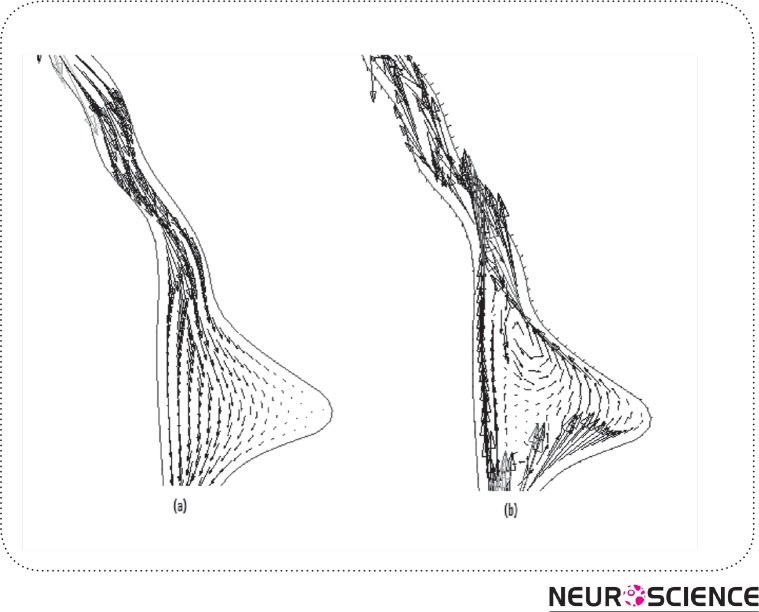

Assuming a pulsatile inflow leads to flow pattern in HVS as presented in Fig. 6 (a)-(b). It displays a primarily caudal-flow in the early on systole of the cardiac sequence (Fig. 6(a)). In the mid-systole, the scale of the CSF-flow velocities goes to its peak. This flow prototype goes on up to the closing stages of the systole. During the diastole, the outflow stops and the CSF-flow changes its course as indicated in Fig. 6 (b). The CSF ascends from the fourth ventricle and also flows reverse into the ventricles as well as the aqueduct of Sylvius.

Figure 6.

CSF flow in aqueduct and 4th Ventricle; (a) flow in systolic time, (b) flow reverses in diastolic time known as back-flow in aqueduct.

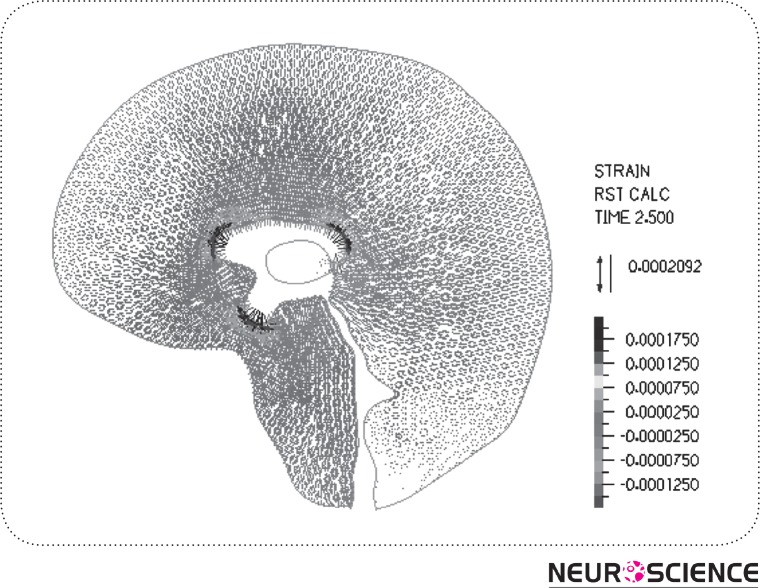

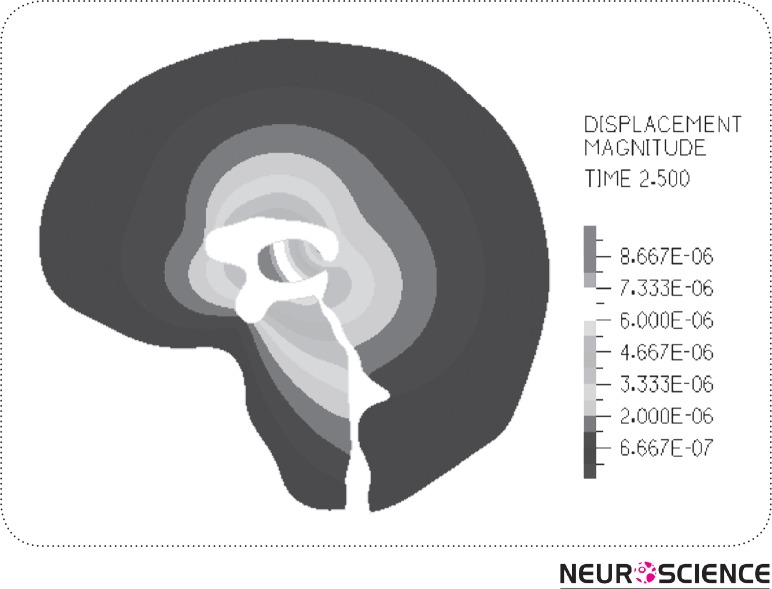

The result of strain distribution and tissue displacements are indicated in Fig. 7-8. As can be seen in Figure 7, the highest strain takes place around the lateral ventricle. Also, in Fig. 8 the parenchyma around the HVS is the most displaced area during a cardiac cycle which is about 0.006 mm and the tissue near the skull has no observable displacement.

Figure 7.

Equivalent strain distribution in surrounding tissue.

Figure 8.

Displacement Distribution of the surrounding tissue (in meters). As can be seen from the picture, the surrounding tissue near the lateral ventricle has the most dispalcement and near the skull the displacement is almost zero.

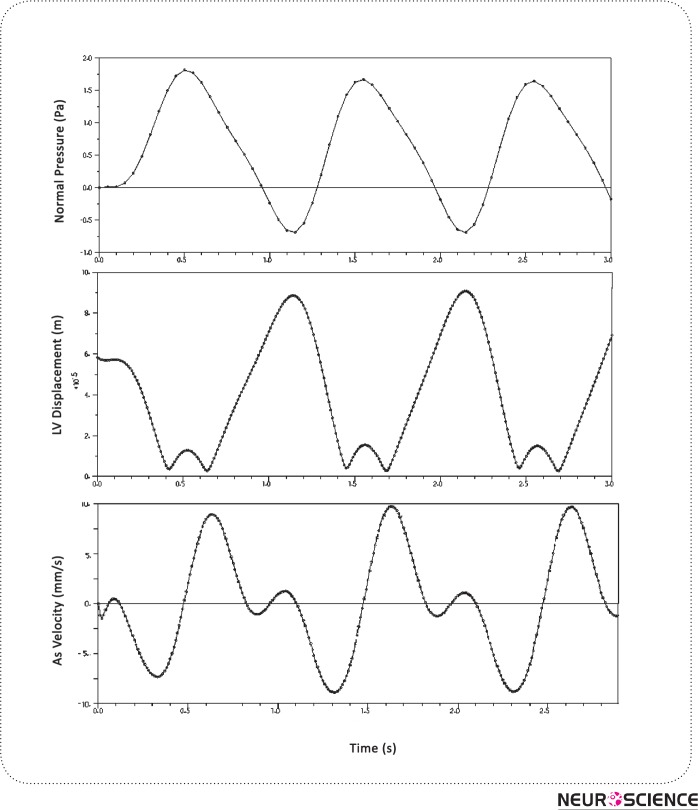

The pulsatile plot of pressure in a region of LV has been depicted in Fig. 9 (a). The values below the zero account for the backflow of CSF in HVS during diastole. Ventricular expansion of 1.5%-2.5% was observed due to the LV wall displacement as depicted in Fig. 9 (b). Moreover, an approximate π/4 phase difference could be observed in Fig. 9 (c) between the CSF velocity cycle and CSF Pressure cycle.

Figure 9.

Pressure, displacement and velicity magnitudes in lateral ventricle. We see the lateral ventricle wall displacement and aqueduct velocity during 3 cardiac cycles

For comparison, the results of previous modeling at the aqueduct region are presented in Table IV.

Table 4.

Comparison of the results between our FSI model and published model (for positive the flow is toward outlet and negative in reverse).

| Models | Aqueduct Velocity | As Pressure Drop | Total Pressure Drop |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linninger [13] | +12.8/-12.9 mm/s | - | 6 Pa |

| Jacobson [6] | +23 mm/s | 2 Pa | 3-10 Pa |

| Fin [8] | 22 mm/s | 0.6-10 Pa | - |

| Kurtcuoglu [11] | -25/+11 mm/s | 20 Pa | - |

| Our model | -6/+8 mm/s | 1.3 Pa | 2.4 Pa |

5. Discussions

Our study not only considered rigid boundary condition but also the surrounding flexible brain tissue interaction effect with pulsatile inflow. The previous simulation results were based on rigid boundary condition for the walls of ventricles. Linninger(Ursino, 1988) modeled the brain effects as a rigid porous media. His investigation showed the necessity of considering surrounding tissue interaction with CSF flow pattern. The brain tissue is a solid material and in some research works has been modeled as an elastic material (Balédent et al., 2004). Also, Fin compared the rigid and deformable models for aqueduct. However, his model considered a solid thickness for the aqueduct wall instead of whole parenchyma interaction without considering the pulsatile in flow. In later publications, Cheng et al. (Yoo et al., 2012) considered the effect of parenchyma as an elastic membrane with different elastic properties and different portions and applying the arbitrary load and reproducing the pulsatile nature of CSF flow.

The pulsatile CSF motion is induced by the CSF generation from the choroid-plexus in the ventricles. The importance of CSF pulsatile behavior has been discussed in previous studies (Miyati et al., 2007; Ye & Bogaert, 2008). Zhuhave indicated that the growth of the vascular bed in the systole resultsinsolidity of the lateral ventricle andswelling of the choroid-plexus leading to CSF-flow out of the ventricles (Hofmann, Warmuth-Metz, Bendszus, & Solymosi, 2000). In a recent study,Linningerdeveloped the CSF pulsatile formation equation considering underlying arterial pulsation synchronized with heart beat(Ursino, 1988). Regarding his idea, we have studied the influence of pulsation in our model by considering a CSF pulsatile formation.

The objective of the current study was to ascertain the velocity characteristics of CSF and CSF pressure distribution in HVS. In fact, the pressure in HVS region is ICP. However,in our modeling we considered zero pressure at the passage of the fourth-ventricle. Therefore, the pressure distribution in HVS was obtained relative to actual outlet pressure. The publishedMRI results are also included in Table IV for comparison.

Comparing the results of rigid and FSI conditions shows that velocity magnitude and pressure drop is about half time when the tissue effects were included. As the CSF passes through the HVS, a portion of its kinetic energy will be consumed to deform the elastic ventricular walls and consequently the surrounding tissue and will be saved there as a potential energy. This is also the reason for velocity differences in rigid and deformable models in contact with solid. Moreover, our FSI model is capable of predicting the LV wall displacement obtained in cine MRI studies. In our modeling, the lateral ventricle enlargement is in good agreement with the published MRI results (Nitz et al., 1992)(Hofmann et al., 2000) (Table III). The pressure drop of not more than 10Pa obtained by Jacobson and later by Aroussiis in good agreement with our results. However, the velocity results show an observable difference. 2D modeling of Linninger(Ursino, 1988) declares the velocity magnitude of 12mm/s in aqueduct and 4 mm/s in Magendie foramina. Our FSI model showsa relatively smaller velocity.

As can be seen from the pressure contour, the pressure varies through the HVS with the greatest pressure drop occurring through the aqueduct, due to higher dynamic pressure caused by large CSF velocity in this region. In the FSI model we obtained 8 mm/s for maximum velocity value and 1.2Pa for pressure drop of the aqueduct region, which is consistent with the findings of Jacobson who showed that a pressure drop of 1.1 Pa is necessary to drive the flow of higher CSF production through the aqueduct. Not only the velocity and pressure distribution magnitude but also the flow diagram is in good agreement with the MRI observation. As seen in Fig. 6, the flow reverses from the 4th ventricle toward the 3rd ventricle in diastolic time. Clinical evidence also validates that the CSF-motion in the AS reverses with each cardiac sequence(Ursino, 1988)(Nitz et al., 1992) (Zhu et al., 2006)(Hofmann et al., 2000) whilst the arterial as well as venous-blood pressure disparity is for all time positive. The event can be justified with the energy storage in brain tissue. The outcome is the return of elastic tissue twist of the ventricular-wall so fluid-flow reverses (Ursino, 1988)(Hofmann et al., 2000). As the cardiac-cycle goes through diastole, pressure falls in the cranium leading to flow of CSF from the spinal-SAS up into the cerebral-SAS and backside into the ventricles (Sivaloganathan et al., 1998).

There is a hypothesis that arteriolar pulsation in the parenchyma is the main cause for ventricular wall displacement and this displacement induces the CSF pulsatile motion (Balédent et al., 2004). In this article, we consider the effect of arteriolar pulsation responsible for the pulsatile CSF flow in HVS (Ursino, 1988)(Nitz et al., 1992) This fact, in addition to elastic brain tissue interaction on CSF flow, produces the diastolic back flow and causes the ventricular wall displacement in the boundary of Solid-Fluid. We have shown that the ventricular wall displacement could be a passive result due to the pulsatile motion. As Grietz and Egnor(Nitz et al., 1992) and also the famous Bering (Miller, 1999) experiments have shown the pulsation should be applied to the CSF formation process from the choroid. This phenomenon was called “a kind of fourth circulation” by Madson..

Also, the MRI results show that there is a phase difference between the CSF velocity which is considered synchronized with heart beat and the LV wall displacement (Ursino, 1988)(Gu et al., 2012). This fact, which is observable in our result as well(Fig. 9 (b,c)), validates our hypothesis which is based on CSF pulsatile generation as a driving force and the LV displacement as a passive result for the incident.

Obtaining the LV displacement and ventricular expansion are new approaches adopted in this study that were accessible with deformable condition considered for HVS. Since no previous modeling has achieved this goal, the results were compared with CINE experiments (Ursino, 1988)(Hofmann et al., 2000)(Lee, Wang, & Mezrich, 1989)(Gu et al., 2012) or the theoretical model of Linninger(Ursino, 1988) which obtained 4-4.5% ventricular expansion for lateral ventricles. This large difference was perhaps due to their approximation of brain tissue effect while our modeling includes the real effect of elastic tissue. Our work confirms the importance of pulsatility of inflow and also the interaction of solid phase by comparing the FSI model and a rigid one with real MRI data (Ursino, 1988)(Nitz et al., 1992) (Hofmann et al., 2000).

Though 2D models provide a quantitative simulation of CSF flow in the ventricles, the qualitative results provided through such models are more reliable. A more realistic 3D model of HVS geometry though seems to yield more accurate results, is a complex and cumbersome task which has not been seen in recent literature. We propose that CSF flow and interaction of the parenchyma to be modeled in a 3D pattern for future studies. Another shortcoming in our modeling is that the brain parenchyma is treated as an elastic material, causing the ventricular walls to return to their previous position after each pulsation. However, as the work of Miller and coworkers (Yoo et al., 2012) has shown, the mechanical behavior of the brain tissue is more appropriately explained with visco-elastic or non-linear hyper elastic models. Another probable pitfall in our 2D model is that the SAS chamber and diffusion of CSF into the venous sinuses has not been considered, which does not seem to be a major obstacle considering the recent advances in CFD software package. Efforts are underway to extend the model presented here in to a 3D model of brain ventricle, SAS and parenchyma, capable of describing the absolute pressure in HVS system. Also we have not considered brain arterial pulsations in our model. The effect of this can be considered for future study.

References

- Balédent, Olivier, Gondry-Jouet, Catherine, Meyer, Marc-Etienne, De Marco, Giovanni, Le Gars, Daniel, Henry-Feugeas, Marie-Cécile, & Idy-Peretti, Ilana . (2004). Relationship Between Cerebrospinal Fluid and Blood Dynamics in Healthy Volunteers and Patients with Communicating Hydrocephalus. Investigative Radiology, 39(1), 45–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitah, Salvador Aznar . (2012). Defining an epidermal stem cell epigenetic network. Nat Cell Biol, 14(7), 652–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopp, Michael, & Portnoy, Harold D . (1980). Systems analysis of intracranial pressure. Journal of Neurosurgery, 53(4), 516–527. doi: 10.3171/jns.1980.53.4.0516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, W. (2001). The state of head injury biomechanics: past, present, and future: part 1. Critical reviews in biomedical engineering, 29(5-6), 441–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greitz, Dan . (2004). Radiological assessment of hydrocephalus: new theories and implications for therapy. Neurosurgical Review, 27(3), 145–165. doi: 10.1007/s10143-004-0326-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Ben J., Duce, James A., Valova, Valentina A., Wang, Bruce, Bush, Ashley I., Petrou, Steven, & Wiley, James S. (2012). The P2X7-mediated scavenger activity of mononuclear phagocytes towards non-opsonized particles and apoptotic cells is inhibited by serum glycoproteins but remains active in cerebrospinal fluid. Journal of Biological Chemistry. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.340885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, Erich, Warmuth-Metz, Monika, Bendszus, Martin, & Solymosi, Lászlò . (2000). Phase-Contrast MR Imaging of the Cervical CSF and Spinal Cord: Volumetric Motion Analysis in Patients with Chiari I Malformation. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 21(1), 151–158 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson EE, Fletcher DF, Morgan MK, Johnston IH. (1996a). Fluid Dynamics of the Cerebral Aqueduct. Pediatr Neurosurg, 996;24:229–236( 10.1159/000121044). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson EE, Fletcher DF, Morgan MK, Johnston IH. (1996b). Fluid Dynamics of the Cerebral Aqueduct. Pediatr Neurosurg, 1996;24:229(236). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Claire F., Newell, Robyn S., Lee, Jae H.T., Cripton, Peter A., & Kwon, Brian K. (9000). The Pressure Distribution of Cerebrospinal Fluid Responds to Residual Compression and Decompression in an Animal Model of Acute Spinal Cord Injury. Spine, Publish Ahead of Print, 10.1097/BRS.1090b1013e31826ba31827cd [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kaczmarek, Mariusz, Subramaniam, Ravi, & Neff, Samuel . (1997). The hydromechanics of hydrocephalus: Steady-state solutions for cylindrical geometry. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 59(2), 295–323. doi: 10.1007/bf02462005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E, Wang, JZ, & Mezrich, R. (1989). Variation of lateral ventricular volume during the cardiac cycle observed by MR imaging. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 10(6), 1145–1149 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmarou, Anthony, Shulman, Kenneth, & Rosende, Roberto M. (1978). A nonlinear analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid system and intracranial pressure dynamics. Journal of Neurosurgery, 48(3), 332–344. doi: 10.3171/jns.1978.48.3.0332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier, U., Zeilinger, F. St, & Kintzel, D. (1999). Diagnostic in Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus: A Mathematical Model for Determination of the ICP-Dependent Resistance and Compliance. Acta Neurochirurgica, 141(9), 941–948. doi: 10.1007/s007010050400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Karol . (1999). Constitutive model of brain tissue suitable for finite element analysis of surgical procedures. Journal of Biomechanics, 32(5), 531–537. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00010-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyati, Tosiaki, Mase, Mitsuhito , Kasai, Harumasa, Hara, Masaki, Yamada, Kazuo, Shibamoto, Yuta, … Luechinger, Roger . (2007). Noninvasive MRI assessment of intracranial compliance in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 26(2), 274–278. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitz, WR, Bradley, WG, Watanabe, AS, Lee, RR, Burgoyne, B, O'Sullivan, RM, & Herbst, MD. (1992). Flow dynamics of cerebrospinal fluid: assessment with phase-contrast velocity MR imaging performed with retrospective cardiac gating. Radiology, 183(2), 395–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrachari, Anirudh R., Podichetty, Jagdeep T., & Madihally, Sundararajan V. (2012). Application of computational fluid dynamics in tissue engineering. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 114(2), 123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2012.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaloganathan, S., Tenti, G., & Drake, J. M. (1998). Mathematical pressure volume models of the cerebrospinal fluid. Applied Mathematics and Computation, 94(2–3), 243–266. doi: 10.1016/s0096-3003(97)10093-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ursino, Mauro. (1988). A mathematical study of human intracranial hydrodynamics part 2—Simulation of clinical tests. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 16(4), 403–416. doi: 10.1007/bf02364626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursino, Mauro, & Lodi, Carlo Alberto. (1997). A simple mathematical model of the interaction between intracranial pressure and cerebral hemodynamics. Journal of Applied Physiology, 82(4), 1256–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, Warren A., Bilodeau, Steve, Orlando, David A., Hoke, Heather A., Frampton, Garrett M., Foster, Charles T., … Young, Richard A. (2012). Enhancer decommissioning by LSD1 during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature, 482(7384), 221–225. doi: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v482/n7384/abs/nature10805.html#supplementary-information [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Yuxiang, & Bogaert, Jan . (2008). Cell therapy in myocardial infarction: emphasis on the role of MRI. European Radiology, 18(3), 548–569. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0777-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, Kyung, Kim, Seok, Chung, Sung, Jeong, Cheol, Jeong, Seong, Curia, Luciana, … Murthy, Hanuman K. (2012). CLINICAL NEUROSCIENCES / Paper No: 40.00Dose-related Reduction of Sevoflurane Requirements to Block Autonomic Hyperreflexia by Remifentanil During Transurethral Litholapaxy in Patients with High Complete Spinal Cord Injury / Paper No: 79.00DIC and Venous Air Embolism during surgical resection of a Giant Meningioma. A case report / Paper No: 155.00Anaesthetic implications for intraoperative high field magnetic resonance imaging in neurosurgery: our experience / Paper No: 296.00Intrathecal baclofen for spasticity and pain / Paper No: 297.00Arixtra (Fondaparinux) as Part of Treament for Patients with Stroke / Paper No: 340.00Cerebral Desaturation Events During Beach Chair Position Shoulder Surgery: Regional Versus General Anesthesia / Paper No: 403.00The relationship between shivering and opioid-induced hyperalgesia induced by high doses of remifentanil in patients undergoing single port gynecologic surgeries / Paper No: 514.00Respiratory support in acute brain injury / Paper No: 542.00To study the incidence and characteristics of postoperative complications during hospital stay in patients undergoing transsphenoidal removal of pituitary tumors / Paper No: 841.00Respiratory complications in the early postoperative period following elective craniotomies / Paper No: 926.00Diagnostic and prognostic importance disoders purine metabolism in acute cerebral ischemia / Paper No: 936.00Early extubation after prolonged intracraneal tumour surgery in children / Paper No: 1090.0Thalamocortical networks participate in propofol-induced unconsciousness: a functional imaging study / Paper No: 1092.0Comparison of preexisting cognitive impairment, amnestic mild cognitive impairment, and multiple domain mild cognitive impairment in men scheduled for coronary artery surgery / Paper No: 1192.0Meta-Analysis on the Accuracy of Neuromonitoring in Awake Patients undergoing Carotid Endarterectomy / Paper No: 1222.0 Glasgow Coma Score in Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury with or without Intracranial Pressure Monitoring / Paper No: 1234.0 Clonidine vs dexmeditomidine in intracranial tumor surgeries: comparison of haemodynamic stability, brain relaxation and emergence. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 108 (suppl 2), ii65–ii74. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer476 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, David C., Xenos, Michalis, Linninger, Andreas A., & Penn, Richard D. (2006). Dynamics of lateral ventricle and cerebrospinal fluid in normal and hydrocephalic brains. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 24(4), 756–770. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]