Abstract

Introduction

Working memory plays a critical role in cognitive processes which are central to our daily life. Neuroimaging studies have shown that one of the most important areas corresponding to the working memory is the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLFPC). This study was aimed to assess whether bilateral modulation of the DLPFC using a noninvasive brain stimulation, namely transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), modifies the working memory function in healthy adults.

Methods

In a randomized sham-controlled cross-over study, 60 subjects (30 Males) received sham and active tDCS in two subgroups (anode left/cathode right and anode right/cathode left) of the DLPFC. Subjects were presented working memory n-back task while the reaction time and accuracy were recorded.

Results

A repeated measures, mixed design ANOVA indicated a significant difference between the type of stimulation (sham vs. active) in anodal stimulation of the left DLPFC with cathodal stimulation of the right DLPFC [F(1,55)= 5.29, P=0.019], but not the inverse polarity worsened accuracy in the 2-back working memory task. There were also no statistically significant changes in speed of working memory [F(1,55)= 0.458,P=0.502] related to type or order of stimulation.

Discussion

The results would imply to a polarity dependence of bilateral tDCS of working memory. Left anodal/ right cathodal stimulation of DLPFC could impair working memory, while the reverser stimulation had no effect. Meaning that bilateral stimulation of DLFC would not be a useful procedure to improve working memory. Further studies are required to understand subtle effects of different tDCS stimulation/inhibition electrode positioning on the working memory.

Keywords: Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex, Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation, Working Memory

1. Introduction

Working memory refers to a the ability responsible for the limited and temporary storage and processing of information for manipulating, recalling or association with other incoming information. According to the central executive model (Baddly, 1986), an attentional control system should be responsible for the strategy selection, control and co-ordination of the various processes involved in short-term storage and more general processing tasks. An important characteristic of this system is a limitation of resources and variations in processing, storage and functions (Salmon et al, 1996).

According to Baddley (1992), working memory transiently stores and processes information underlying attention. These comprise functions such as learning, language and reasoning which are supported with complex cognitive operations. Furthermore, it plays a critical role in cognitive processes which are central to one's daily life. Several brain regions are shown to be involved in working memory processing. They include dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), inferior frontal gyrus, hippocampus, globuspallidus, caudate nucleus, putamen, amygdala (Sadleir, Vannorsdall, Schretlen, Gordon, 2010), dorsal occipital area, frontal eye field, intraparietal sulcus, inferior temporal gyrus, posterior middle frontal gyrus, and the superior parietal lobule (Pessoa et al., 2002). Functional neuroimaging studies however have suggested a dominant role for DLPFC in this respect (Paulesu et al, 1993). This area becomes highly activated when precise information monitoring for spatial, non-spatial, verbal and visual stimuli is required (Funahashi et al., 1993). Meanwhile, the medial parts of prefrontal cortex contribute to the maintenance and retrieval of the recently encoded information (Zimmer, 2008, Mottaghy et al. 2000).

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) is a non-invasive method to manipulate the cortical activity using a continuous weak electric current induced by large electrodes placed on the scalp of the subject (Nitsche, et al., 2008). The amount of the electrical current going to the brain is enough to cause focal and prolonged, but yet reversible shifts on cortical excitability (Wagner et al., 2007, Miranda et al., 2006). These manipulations have diverse effects on brain functioning, depend on site, polarity and size of the stimulation (Javadi & Walsh, 2012). This method has been proposed to be applied for the rehabilitation of working memory deficits seen in mental or neurological disorders such as Alzheimer, depression or Parkinson's Diseases (Ferrucci et al, 2008; Kalu et al, 2012; Boggio et al, 2006), while more evidence is required to support this application. A growing body of evidence has substantiated that different tDCS electrode positioning result in various modulatory effects both normal subjects and patients (Boggio et al., 2006; Ferrucci et al, 2008; Fregni et al., 2005; Marshall et al., 2005). Fregni et al. (2005) found that 1 mA of online anodal tDCS over the left DLPFC for a period of 10 minutes, enhances the accuracy of the 3-back working memory task, compared to sham and cathodal tDCS applied to the same area. However, bilateral tDCS stimulation of DLPFC during the modified Sternberg working memory task either for the anodal or cathodal stimulation, increases reaction time (Marshall et al., 2005). Ohn et al. (2008) assessed the working memory during 30 minutes under 1 mA anodal tDCS stimulation applied to left DLPFC. They identified a linear improvement of the working memory over time. In a similar report, a 2 mA tDCS stimulation was shown to improve the working memory in patients with Parkinson's Disease, whereas 1 mA stimulation led to no significant effect (Boggio et al. 2006). Ferrucci et al. (2008) showed that either the anodal or cathodal stimulation over the cerebellum did not alter the working memory proficiency in Sternberg's test. In another study, they reported that one anodal session of temporal cortex in patients with Alzheimer's Disease improved memory performance, whereas the impact of applying several sessions of stimulation on long-term improvement remained controversial. More recently, Mulquiney, et.al (2011) have found that the anodal tDCS over the left DLPFC may significantly improve the performance speed in a 2-back working memory task, while this is not shown to have effects on the accuracy of performance. These finding would imply that effect of tDCS heavily depend on various variables, including: the side, the power, the polarity of stimulation.

Taken the above insights together, the aim of the current is to investigate any possible effects of the simultaneous excitation of the bilateral DLPFC on working memory.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Sixty healthy college students (30 male) were recruited from Shahid Beheshti University. Participants were randomly assigned into two subgroups (15 female in each) with respect to the side and polarity of the stimulation, i.e. left anodal/ right cathodal vs. left cathodal/ right anodal stimulation of the DLPFC. The mean and standard deviation of age for the groups were; 22.3 years, (sd= 0.86) And 21.2 years, (sd=0.67). The difference in age was not significant. Participants gave an informed consent form for taking part in the study. All of them met the inclusion criteria for tDCS (Nitsche, et al., 2008), and none had previously experienced tDCS experiments. Exclusion criteria were substance abuse, history of serious head injury, or any other serious medical condition interfering with tDCS application or working memory performance.

2.2. Design

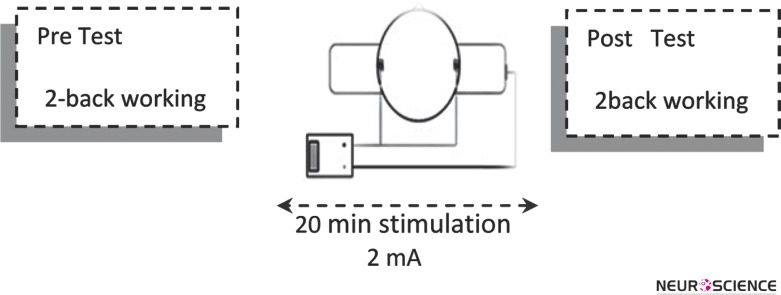

The study had a single-blinded 2x2x2 repeated measure design. Each participant underwent two sessions with at least 3 days interval to minimize any potential carry over effect of stimulation. They received active or sham tDCS stimulation for 20 minutes while performed the task just before and after to the stimulation. The stimulation session's order was randomized and counterbalanced across participants to overcome the learning effect on the outcome measures. A same 2-back working memory task was used in all pre/ post assessments. This task is a sensitive measure to cognitive changes in a variety of disorders and has minimal learning effects, making it an ideal task for repeated testing (Maruff et al., 2009; Mulquiny et al., 2011). All stimulation sessions were carried out by the same researcher (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sequence of task presentation and stimulation. Participants were first required to perform 2-back working memory task. Then the tDCS stimulation was applied over left and right DLPFC, during 20 minutes. Finally, post 2-back working memory task was assessed.

2.3. Procedure

Participants were briefed about the procedure at the beginning of each session. The location of right and left DLPFC were determined based on Dasilva et al.'s (2011) method. Each participant was instructed to response to a computerized working memory task by pressing button 1 or 2 as he or she decided whether each figure was identical to the one presented two earlier in the sequence. They were instructed to press the key 1 if the presented figure was the same as the figure presented two stimuli previously, and if not to press the key 2.

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Working Memory Task

A visual sequential 2-back figure working memory (Mull & Seyal, 2001) was used in this study. Subjects were presented with a pseudo-random set of six figures. The stimuli were generated using the MATLAB software. A 2-back working memory task, is considered as an active task, since the working memory should be continuously updated (Zimmer, 2008). Subject were asked to press the key 1 if the presented figure was the same as the figure presented two stimuli previously, and if not, press the key 2. One hundred figures which were divided into six different series were prepared in the task and totally 20 correct responses were obtained from each set. Figures were presented randomly and sequentially while for each figure the subject had to memorize it then press the key 1 or 2 based on what image he or she sees in the next sequence. Subjects’ speed as well as correct responses was recorded. The applied 2-back working memory task remained the same for all participants.

2.4.2. Stimulation

Stimulation was applied with a battery-driven device (Activa Dose Iontophoresis manufactured by ActivaTek), which was capable of delivering the anodal, cathodal direct current and sham direct current required for this study. Direct current was delivered through two 25 cm2 (5×5) electrodes, covered by sponge pad soaked in sodium chloride solution. The stimulator was set to fade in and out over a period of 30s at the beginning and the end of the stimulation session.

2.4.2.1. Active Stimulation

Active stimulation was applied at 2 mA. The left cathodal/right anodal stimulation was conducted with the anode placed over the right DLPFC and cathode over the left DLPFC, and in the reverse order for the left anodal / right cathodal stimulation. The electrodes were positioned with an elastic band according to electrode placement measuring method.

2.4.2.2. Sham Stimulation

During sham stimulation by positioning electrodes as same as active tDCS condition a constant current faded in for 30 s before being immediately faded out for 30 s, and the tingling sensation associated with tDCS was noticeable only for the first 1 min. This coding and setting required the subject to be blind, resulting in a single-blinded experiment.

2.4.3. Statistical Analysis

For both accuracy and speed, we conducted a 2 × 2 × 2 ANOVA repeated measure (pre/post × electrode position× stimulation) of participants’ working memory. We conducted a general linear model repeated measures analysis on the factors working memory scores (pre vs. post) and tDCS stimulation condition (active vs. sham stimulation) was employed. To determine more specifically whether the accuracy after tDCS differed in stimulation condition paired samples for the intra group active versus sham comparisons, two-tailed analysis with significance level of P < 0.05, not adjusted for multiple comparisons were performed. The dependent variables were checked for the normal distribution.

3. Results

3.1. Results of Working Memory Accuracy

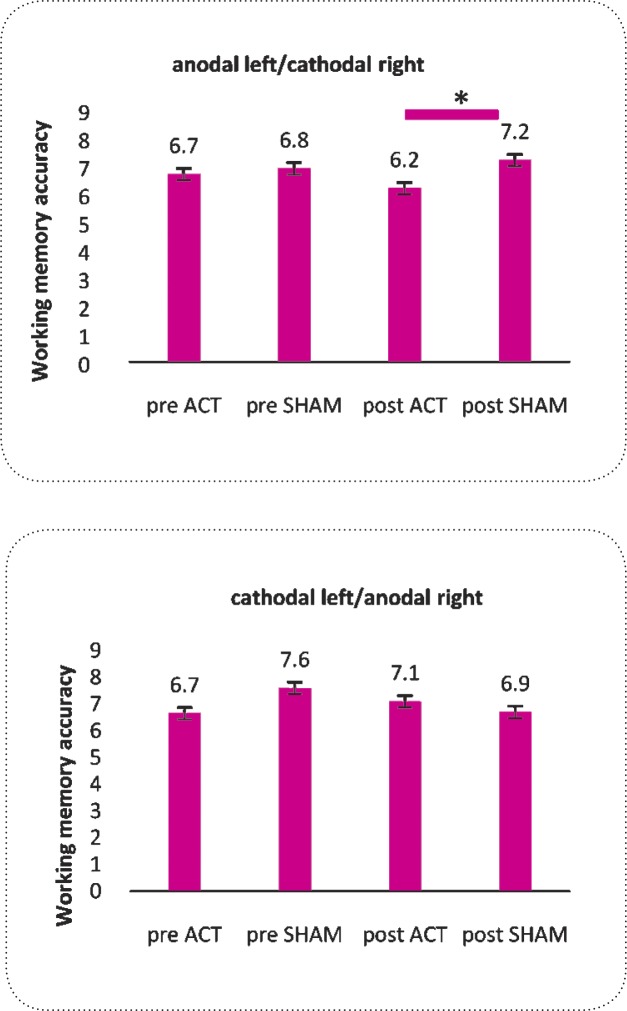

Repeated measure-ANOVA revealed that the effect of “stimulation” condition was significant [F (1, 55)=5.29, P=0.019]. Similarly, the interaction of “order” דstimulation” × “electrode position” [F(1,55)=2.404 P=0.045] was significant (Table 2). To overview this finding we should consider the differences which are outlined in Figure 2. Post-hoc Paired t test showed that there was significant differences between the accuracy in post stimulation conditions (sham vs. active) only in the left anodal/ right cathodal tDCS stimulation [t=-2.894, df=28, P=0.007], but not in the left cathodal/ right anodal tDCS stimulation [t=0.497, df=27, P= 0.623]. Independent samples t tests did not reveal significant differences between the post stimulation results of active or sham types of electrode positioning (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Results of the repeated measure of ANOVAs used to compare accuracy and speed of the anodal left/cathodal right and cathodal left/anodal right of DLPFC groups.

| Factors | F statistic | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working memory accuracy | Stimulation | F (1,55)=5.29 | 0.019 |

| Stimulation* Electrode position | F (1,55)=0.018 | 0.894 | |

| Order | F (1,55)=0.572 | 0.453 | |

| Order* Electrode position | F (1,55)=0.423 | 0.518 | |

| Order*Stimulation | F (1,55)=0.156 | 0.312 | |

| Stimulation*Order*Electrode position | F (1,55)=2.404 | 0.045 | |

| Working memory speed | Stimulation | F (1,55)=0.458 | 0.502 |

| Stimulation* Electrode position | F (1,55)=0.313 | 0579 | |

| Order | F (1,55)=39.03 | 0.000 | |

| Order* Electrode position | F (1,55)=0.154 | 0.696 | |

| Order*Stimulation | F (1,55)=0.49 | 0.825 | |

| Stimulation*Order*Electrode position | F (1,55)=0.123 | 0.728 |

Boldface highlights important comparisons

Figure 2.

Absolute change of visual working memory revealed in post active and post sham conditions in left anodal/right cathodal tDCS stimulation of normal subjects (t test, P = 0.007). There are no differences between conditions in cathodal left/anodal right (t test, P> 0.05). Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

3.2. Results of Working Memory Speed

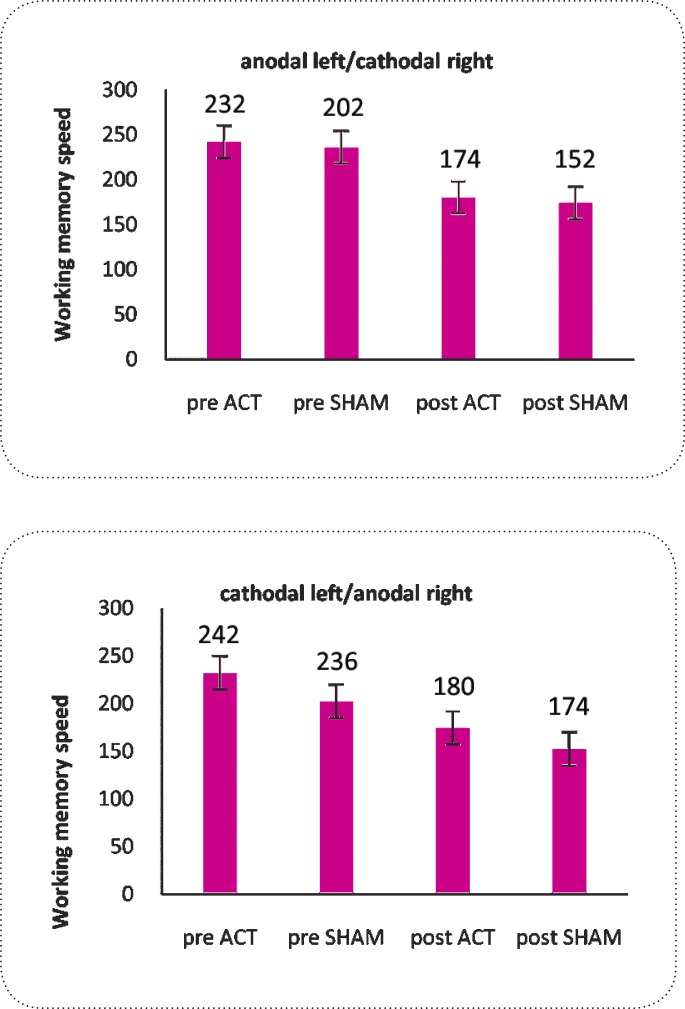

For the working memory speed, repeated measure- ANOVA revealed that there was no significant effect of “stimulation” [F(1,55)= 0.458,P=0.502] or interaction of “stimulation” × “order” × “electrode position” [F(1,55)= 0.123, P=0.728] (Table 2). There was a significant effect of “order” [F(1,55)= 0.458,P=0.000]. As presented in Figure 3, this difference was due to the familiarity with procedure of the test in which the speed of performance increases in post-test. This result indicates that participants were not significantly faster in responding neither in the active (Anodal and Cathodal) stimulation nor sham trials (Table 1/Figure 3) and the response speeds were similar when participants responded in pre and post of stimulation setting(Table 1/Figure 3).

Figure 3.

There is no significant difference in the mean speed between conditions (sham vs. active stimulation) in both protocols. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

Table 1.

Means and standard error of mean (SEM) for accuracy and speed on 2-back visual working memory outcome measures

| Active stimulation | Sham stimulation | Statistics within a group | Statistic Between group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-tDCS | Post-tDCS | Post-tDCS | Post-tDCS | ||||

| Accuracy | Anodal left/ Cathodal right/ | 6.7±1.8 | 6.2±1 | 6.8±2 | 7.2±1.1 | 0.007a | 0.082 |

| Cathodal left/ Anodal right | 6.7±0.9 | 7.1±0.9 | 7.6±1 | 6.9±0.9 | 0.623 | ||

| Speed | Anodal left/ Cathodal right | 232±74 | 174±41 | 202±47 | 152±10 | n.t. | n.t. |

| Cathodal left/ Anodal right | 242±95 | 180±20 | 236±15 | 174±10 | n.t. | ||

n.t., not tested; statistic between groups is independent samples t test electrode positioning. Statistics within a group are paired samples t test post active versus post sham tDCS.

P>0.05.

4. Discussion

We attempted to investigate the effects of the bilateral stimulation of the DLPFC on working memory. Our results indicated that the left anodal / right cathodal stimulation of the DLPFC impaired the accuracy of the task performance as compared to the sham stimulation of the same area. Both stimulation types had no effects on the speed of working memory performance. Our results were incongruent with previous studies (Fregni et al, 2005; Ohn et al, 2008; javadi & walsh, 2011; Javadi & Cheng, 2011), which showed that anodal stimulation of the left DLPFC enhances the working memory performance.

These data raises the question of whether the difference in our results with previous studies is due to the type of stimulation electrode position. In other words, could simultaneous stimulation of right DLPFC with left DLPFC interferes with the working memory performance.

Incongruent with literature about brain stimulation effects on working memory, the present study showed that the left anodal stimulation of DLPFC with simultaneous cathodal stimulation of right DLPFC not only failed to enhance the accuracy performance of the participants, but also decreased the accuracy in their working memory performance. Though, we should consider to the role of the cathode electrode applied over the right DLPFC.

Some neuroimaging studies (Funahashi et al, 1989, 1990, 1991; Salmon et al, 1996) have demonstrated the right DLPFC activation during a visual working memory task. Likewise, some other report have showen that this region is involved in working memory (D'Esposito et al, 1998; Smith and Jonides, 1999). Moreover, lesion studies (Goldman & Rosvold, 1970; Bauer & Fuster, 1976; Funahashi, Bruce, & Goldman-Rakic, 1993) have indicated that when this area is damaged, the working memory is notably affected. It has been found that transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) of the right DLPFC with disruption of function, results in impaired visual working memory capacity (Oliveri et al., 2001; Turatto, Sandrini, & Miniussi, 2004, Sligte et al, 2011). It should be noted that this study measured the working memory performance with a visual 2-back working memory task. Thus, present results are in line to confirm the role of the right DLPFC on visual working memory, based on which dampening the right DLPFC leads to the performance deterioration in some aspects of cognitive functions such as the visual working memory.

To distinguish the role of the right and left DLPFC in visual working memory, our results suggest that the involvement of the left prefrontal area in visual working memory depends on the verbal encoding of visual stimuli (Smith and Jonides, 1997), whereas the stimuli used in this study were unfamiliar and unmeaning images, thus so difficult to use in verbal encoding with. Therefore, with respect to more dominant role of the right prefrontal on image-based visual working memory than the left DLPFC (Hong et al, 2000), we may assume that the disruption of the right DLPFC function in left anodal/right cathodal stimulation impaired the accuracy by interfering in processing of visual stimuli in working memory performance.

On the other hand, methodological consideration should be entertained. Our study, however differs with previous studies in a several ways. The stimulation intensity in our study was 2 mA, while the previous studies used 1-2 mA. This consideration is important that stimulation intensity is a critical parameter, in which Boggio et al (2006) showed that 2 mA versus 1 mA current stimulation over the left DLPFC can enhance the working memory in patients with Parkinson's Disease. In addition, we tested the working memory performance before and after the stimulation, whereas others (Fregni et al, 2005; Ohn et al, 2008; Boggio et al, 2008; Jvadi and Walsh, 2011) tested this during the online stimulation. Some evidences suggest that stimulation of the brain areas during the task accomplishment have different effect in comparison with offline stimulation (Nitsche &Paulus, 2001). Moreover, the duration of stimulation in this study was 20 min, which was higher than other studies. We applied bilateral stimulation, in which Ohn et al (2008) confirmed that longer stimulation was enhanced working memory performance. Although, some other studies (Fregni et al, 2005; Ohn et al, 2008; Javadi & Walsh, 2011; Mulquiney et al, 2011; Javadi& Cheng, 2011) used unilateral stimulation of the left DLPFC, It has been shown that electrode positioning affects the flow of the current and so likely the stimulated brain area (Im et al, 2008; Nitsche M, Paulus, 2000). However, considering Marshall et al (2005) study in which they used the bilateral intermittent stimulation of the lateral prefrontal cortex, it should be noted that this type of electrode positioning impairs the response selection-related processing. Taken together, it seems that the bilateral stimulation of DLPFC in present study was responsible for the impairment of accuracy and exerted declining effects on working memory. This observation is important as it might indicate that the bilateral stimulation can affect brain in a different way compared to unilateral stimulation. Therefore, it seems likely that other unilateral or bilateral electrode positioning lead to a significant improvement in the working memory accuracy.

With regard to the speed of working memory, bilateral stimulation of DLPFC results in slowing the speed in working memory (Marshall et al, 2005). Discrepancy in our finding with others’ results may be due to the task type and current. We examined the 2-back working memory task, whereas they tested Sternberg's working memory task. In addition, we applied the constant current, while they used an intermittent stimulation during the experiment. In another study, Left anodal stimulation of the DLPFC enhanced the speed of the performance in working memory task (Mulquiney et al, 2011) whereas, some other works (Fregni et al, 2005; Ohn et al, 2008; Javadi and Walsh, 2011; Jvadi & Cheng, 2011) showed that the anodal stimulation of the left DLPFC did not alter the speed of working memory performance. In the present study, the bilateral stimulation effect on speed was in line with the two later reports. Thus, we can acclaim that type of electrode positioning may meaningfully affect the operations in working memory.

With respect to tDCS, in future studies it may also be advantageous to investigate the role of the right DLPFC in working memory performance with other electrode positioning. In the previous brain stimulation studies, little attention is paid to the role of the right DLPFC in working memory performance. While the right DLPFC is shown to be involved in an extended range of working memory dimentions (Zimmer, 2008; Paulesu et al, 1993; Salmon et al, 1996). Moreover, it should be noted that there is little definite evidence explaining whether the effect of tDCS in working memory is indeed via modulation of the DLPFC excitability and if yes, under what possible mechanism(s)? Further studies should proceed to investigate the functional differences between the right and left DLPFC in visual working memory.

In summary, our study indicated that tDCS effect on working memory performance, is dependent to the electrode positioning, and Bilateral stimulation of DLPFC have negative effect on the accuracy of performance upon a working memory task.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to Dr.Vahid Nejati for providing the n-back task and Mehrshad Golesorkhi for the helpful revision of our manuscript.

References

- Baddeley, A. (1992). Working memory. Science. 225, 556–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley, A., Logie, R. H., Bressi, S., Delia Sala, S., & Spinnler, H. (1986). Dementia and working memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 38, 603–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, R. H., & Fuster, J. M. (1976). Delayed-matching and delayed-response deficit from cooling dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in monkeys. Journal of Comparative Physiology Pschology. 90(3), 293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggio, P.S., Ferrucci, R., Rigonatti, S.P., Covre, P., Nitsche, M., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2006). Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on working memory in patients with Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neurological Science. 249(1), 31–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, C.E., & D'Esposito, M. (2003). Persistent activity in the prefrontal cortex during working memory. Trends in Cognitive Neuroscience. 7(9), 415–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DaSilva, A., Volz, M.S., Bikson, M., & Fregni, F. (2011). Electrode Positioning and Montage in Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 51(10), 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmer, S., Burkard, M., Renz, B., Meyer, M., & Jancke, L. (2009). Direct current induced short-term modulation of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex while learning auditory presented nouns. Behavioral Brain Function. 5, 1–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci, R., Marceglia, S., & Vergari, M. (2008). Cerebellar transcranial direct current stimulation impairs the practice-dependent proficiency increase in working memory. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 20(9), 1687–1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci, R., Mameli, F., Guidi, I., Mrakic-Sposta, S., Vergari, M, & Marceglia, S, et al. (2008). Transcranial direct current stimulation improves recognition memory in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 71(7), 493–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregni, F., Boggio, P.S., Nitsche, M., Bermpohl, F., Antal, A., Feredoes, E., Marcolin, M.A., Rigonatti, S.P., Silva, M.T.A., Paulus, W., Pascual-Leone, A. (2005). Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation of prefrontal cortex enhances working memory. Experimental Brain Research. 166, 23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funahashi, S., Bruce, C. J., & Goldman-Rakic, P. S. (1989). Mnemonic coding of visual space in the monkey's dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology. 61(2), 331–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funahashi, S., Bruce, C. J., & Goldman-Rakic, P. S. (1990). Visuospatial coding in primate prefrontal neurons revealed by oculomotor paradigms. Journal of Neurophysiology. 63(4), 814–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funahashi, S., Bruce, C. J., & Goldman-Rakic, P. S. (1991). Neuronal activity related to saccadic eye movements in the monkey's dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology. 65(6), 1464–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funahashi, S., Bruce, C.J., & Goldman-Rakic, P.S. (1993). Dorso-lateral prefrontal lesions and oculomotor delayed-response performance: evidence for mnemonic “scotomas.”. Journal of Neuroscience. 13, 1479–1497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, P. S., & Rosvold, H. E. (1970). Localization of function within the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of the rhesus monkey. Experimental Neurology. 27(2), 291–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, K. S., Lee, S. K., Kim, J. Y., Kim, K. K., & Nam, H. (2000). Visual working memory revealed by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 181, 50–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im, C., Jung, H., Choi, J., Lee, S., & Jung, K. (2008). Determination of optimal electrode positions for transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Physics Medical Biology. 53,(11), 219–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javadi, AH., & Walsh, V. (2012). Transcranial direct current stimulation applied over left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex modulates declarative verbal memory. Brain Stimulation. 5, 231–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalu, UG., Sexton, CE., Loo, CK., Ebmeier, KP. (2012). Transcranial direct current stimulation in the treatment of major depression: a meta-analysis, Psychological Medicine. 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, L., Mölle, M., Siebner, H. R., & Born, J. (2005). Bifrontaltranscranial direct current stimulation slows reaction time in a working memory task. Biomed Central Neuroscience. 6(230), 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruff, P., Thomas, E., Cysique, L., Brew, B., Collie, A., & Snyder, P. (2009). Validity of the CogState brief battery: relationship to standardized tests and sensitivity to cognitive impairment in mild traumatic brain injury, schizophrenia, and AIDS dementia complex. Arch Clinical Neuropsychology. 24(2), 168–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, P. C., Lomarev, M., & Hallett, M. (2006). Modeling the current distribution during transcranial direct current stimulation. Clinical Neurophysiology. 117(7), 1623–1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottaghy, F.M., Krause, B.J., Kemna, L.J., Topper, R., Tellmann, L., Beu, M., Pascual-Leone, A., Muller-Gartner, H.W. (2000). Modulation of the neuronal circuitry subserving working memory in healthy human subjects by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neuroscience Letter. 280, 167–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mull, B.R., & Seyal, M. (2001). Transcranial magnetic stimulation of left prefrontal cortex impairs working memory. Clinical Neurophysiology. 112, 1672–1675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulquiney, P. G., Hoy, K. E., Daskalakis, Z. J, & Fitzgerald, P. B (2011). Improving working memory: Exploring the effect of transcranial random noise stimulation and transcranial direct current stimulation on the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Clinical Neurophysiology. 122(12), 2384–2389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche, M. A., Cohen, L. G., Wassermann, E. M., Priori, A., Lang, N., Antal, A., Paulus, W., Hummel, F., Boggio, P. S., Fregni, F., Pascual-Leone, A. (2008). Transcranial direct current stimulation: State of the art. Journal of Brain Stimulation. 1, 206–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche, M., & Paulus, W. (2000). Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. Journal of Physiology. 527(3), 633–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche, M. A., & Paulus, W. (2001). Sustained excitability elevations induced by transcranial DC motor cortex stimulation in humans. Neurology. 57(10), 1899–1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohn, S. H., Park, C., Yoo, W., Ko, M., Choi, K.P., & Kim, G. (2008). Time-dependent effect oftranscranial direct current stimulation on the enhancement of working memory. Neuroreport. 19(1), 43–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveri, M., Turriziani, P., Carlesimo, G. A., Koch, G., Tomaiuolo, F., & Panella, M. (2001). Parieto-frontal interactions in visual-object and visual-spatial working memory: Evidence from transcranial magnetic stimulation. Cerebral Cortex. 11(7), 606–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen, A.M., Evans, A.C., & Petrides, M. (1996). Evidence for a two-stage model of spatial working memory processing within the lateral frontal cortex: a positron emission tomography study. Cerebral Cortex. 6(1), 31–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulesu, E., Frith, C. D., Bench, C. J., Bottini, G., Grasby, P. G., & FrackowiakR, S. J. (1993). Functional anatomy of working memory: the visuospatial ‘sketchpad’. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow Metabolism. 1, 552–557 [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa, L., Gutierrez, E., Bandettini, P., & Ungerleider, L. (2002). Neural correlates of visual working memory: fMRI amplitude predicts task performance. Neuron. 35(5), 975–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrides, M. (2005). Lateral prefrontal cortex: architectonic and functional organization. Biological Science. 360(1456), 781–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadleir, R. J., Vannorsdall, T. D., Schretlen, D. J., & Gordon, B. (2010). Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in a realistic head model. NeuroImage. 51, 1310–1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon, E., Van der Linden, M., Collette, F., Delfiore, G., Maquet, P., Degueldre, C., Luxen, A., Franck, G. (1996). Regional brain activity during working memory tasks. Brain. 119, 1617–1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sligte, I. G., Wokke, M. E., Tesselaar, J. P., Scholte, H. S., & Lamme, V. A.F. (2011). Magnetic stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex dissociates fragile visual short-term memory from visual working memory. Neuropsychologia. 49, 1578–1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz, B. E., Halgren, E., Fuster, J. M., Simpkins, E., Gee, M., & Mandelkern, M. (1995). Cortical metabolic activation in humans during a visual memory task. Cerebral Cortex. 5, 205–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turatto, M., Sandrini, M., & Miniussi, C. (2004). The role of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in visual change awareness. Neuroreport. 15(16), 2549–2552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, T., Fregni, F., Fecteau, S., Grodzinsky, A., Zahn, M., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2007). Transcranial direct current stimulation: a computer-based human model study. Neuroimage. 35(3), 1113–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, H. (2008). Visual and spatial working memory: From boxes to networks. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral. Reviews. 32, 1373–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]