Abstract

Retrotransposons make up roughly 50% of the mammalian genome and have played an important role in genome evolution. A small fraction of non-LTR retrotransposons, LINE-1 and SINE elements, is currently active in the human genome. These elements move in our genome using an intermediate RNA and a reverse transcriptase activity by a copy and paste mechanism. Their ongoing mobilization can impact the human genome leading to several human disorders. However, how the cell controls the activity of these elements minimizing their mutagenic effect is not fully understood. Recent studies have highlighted that the intermediate RNA of retrotransposons is a target of different mechanisms that limit the mobilization of endogenous retrotransposons in mammals. Here, we provide an overview of recent discoveries that show how RNA processing events can act to control the activity of mammalian retrotransposons and discuss several arising questions that remain to be answered.

Keywords: LINE-1, SINE-1, retrotransposon, Microprocessor, small RNAs, DGCR8, Drosha, transposable elements, Dicer, microRNAs

It is becoming increasingly evident that Transposable Elements (TEs) have been instrumental in shaping eukaryotic genomes. Indeed, TEs are responsible for the generation of at least half of the human genome,1 and although most TE insertions are “molecular fossils,” which have lost the ability to mobilize, active TEs continue to impact our genome.2 At present, only members of the non-LTR retrotransposon class (LINE-1, Alu, and SVA) are active in the human genome.3 Long Interspersed Element-1 (LINE-1 or L1) elements constitute 17% of our genomic mass, and are the only active class of autonomous retrotransposons in humans.1,2 However, only 80–100 L1 elements per genome are capable of mobilization and are termed retrotransposition competent L1s (RC-L1s).4,5 Additionally, SVA (a repetitive element named after its main components, SINE, VNTR and Alu) and Alu elements belong to the class SINE (short interspersed elements), which are non-autonomous retrotransposons mobilized using the enzymatic machinery encoded by RC-L1s.6-8 Non-LTR retrotransposons move in genomes using a “copy and paste” mechanism, which involves reverse transcription of an intermediate RNA and insertion in a new genomic location (reviewed in refs. 2, 9, and 10). Notably, the retrotransposition mechanism of non-LTR retrotransposons is fundamentally different to the process of LTR retrotranspososition, as non-LTR reverse transcription occurs in the nucleus, at the site of insertion. Finally, RC-L1s are also responsible for the generation of processed pseudogenes,11-13 and the preferential mobilization of certain non-coding cellular RNAs.14-16 Thus, the activity of a single type of TE has generated a third of our genome and their activity continues to impact our genome.

A human RC-L1 comprises a 6 kb sequence containing a ~900 bp 5′untranslated region (UTR), two intact Open Reading Frames (ORFs), a short 3′UTR that ends in a poly-A tail and are usually flanked by variable length Target Site Duplications (TSDs, reviewed in refs. 9, 10, and 17). ORF1 encodes a ~40 KDa protein with RNA binding and nucleic acid chaperone activity,18,19 while ORF2 encodes a ~150 KDa protein with ENdonuclease (EN)20 and Reverse Transcriptase (RT) activities.21 Both proteins are strictly required for L1 retrotransposition.22 Retrotransposition starts with the generation of a full-length mRNA from an RC-L1 at a discrete genomic location using an internal promoter located in its 5′UTR.23 Notably, the 5′UTR of human LINE-1s also contains a conserved antisense-promoter of unknown function (AS24,25). Upon maturation, the L1 mRNA is exported to the cytoplasm where translation takes place.26,27 Both encoded proteins presumably bind back to the same mRNA from which they were translated, forming a RiboNucleoprotein Particle (RNP) that is a supposed retrotransposition intermediate.28-30

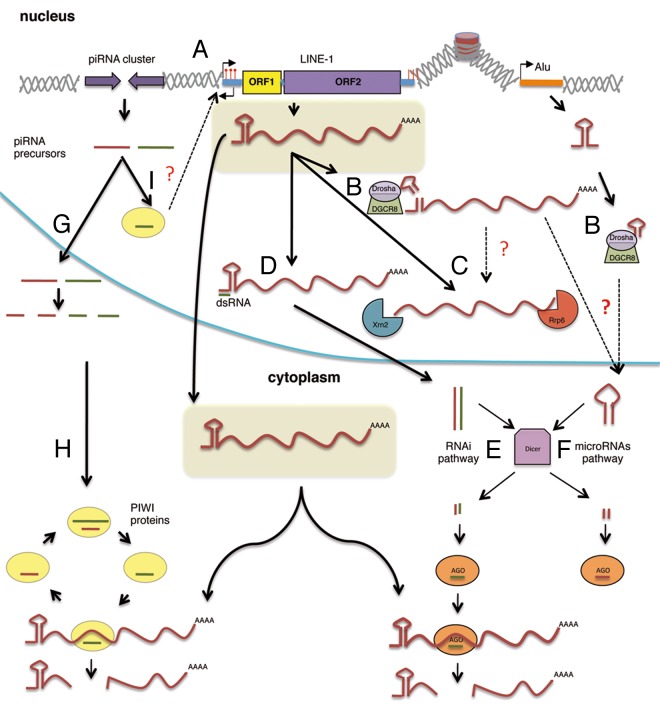

The ongoing activity of TEs may result in insertional mutagenesis processes that could accumulate throughout the human genome and could lead to negative consequences for the cells/tissues affected. Indeed, TE mobilization processes has been associated with almost 100 human disorders31 due to the disruption of a gene unit, by alteration of splicing, by gross alterations at the insertion site or by interfering with transcription among other mechanisms (reviewed in refs. 2, 9, 10, and 31). Given that retroelements can affect the genome in a myriad of ways, it is not surprising that the cell has generated diverse mechanisms to regulate their activity. A main target in TE regulation is the TE intermediate RNA, as this serves as a template to generate a new insertion, and is also required for protein translation in the case of autonomous elements (Fig. 1). Indeed, the majority of methylated cytosines in human genomic DNA occur in repetitive sequences and it has been proposed that DNA methylation evolved primarily as a defense mechanism against TEs.32 Notably, the 5′UTR of mammalian L1s contains a CpG island and L1 expression has been shown to be repressed by DNA-methylation of this region.32,33 Somatic human tissues may contain most L1-CpG islands methylated, but these promoters are hypomethylated during early embryogenesis.34 Thus, it is considered that new TE insertions in humans can be accumulated during early embryogenesis (reviewed in ref. 35). Notably, recent data by several laboratories have revealed that RNA-derived processes may represent an additional layer of regulation, that is part of a dynamic battlefront to control TE mobilization (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Regulation of mammalian retrotransposons at the RNA level. (A) DNA-Methylation of L1 promoters (5′UTR) inhibits its expression. (B) The Microprocessor process structured regions in Alu and L1 derived transcripts, reducing their levels. (C) L1-RNAs can be degraded by the exosome-associated 3′→5′ exoribonuclease Rrp6 and the 5′→3′ exoribonuclease Xrn2; these may occur also after being cleaved by Microprocessor. (D) Double-strand RNAs produced by transcription from both sense and antisense promoters may inhibit L1 retrotransposition by an RNAi mechanism (E). (E) siRNAs are generated from dsRNA in the cytoplasm by Dicer processing and loaded onto AGO proteins targeting L1 RNAs. (F) The processing of L1 and Alu RNAs by the Microprocessor could generate a pre-microRNA-like structure that could be further processed by Dicer in the cytoplasm, generating mature miRNAs loaded in AGO proteins. (G) piRNAs are processed from RNA precursors that are transcribed from particular intergenic repetitive elements known as piRNA clusters. (H) Primary piRNAs are amplified through the ping-pong pathway. Thus, two different piwi proteins, MILI and MIWI2, are associated with sense (brown line) and antisense piRNAs (green line), respectively. piRNAs then may act as guides to cleave complementary transposon transcripts, which requires the endonuclease activity of piwi proteins. (I) Some piwi-like proteins are also localized in the nucleus, where they might participate in DNA-methylation TE sequences (A).

RNA-Mediated Mechanisms of TE Control

A class of small RNAs, Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), is associated with the Piwi clade of Argonautes and acts to repress mobile genetic elements in the germline of both Drosophila and mammals36 (Fig. 1, left side). piRNAs are generated by RNA-transcription of long TE clusters, resulting in the accumulation of short mature piRNAs in the cytoplasm by the ping-pong mechanism (reviewed in ref. 36). piRNAs then act as guides to destroy complementary transposon transcripts by endonucleolytic cleavage (i.e., within piwi complexes36). Briefly, during the ping-pong cycle, primary piRNAs are processed and loaded into MILI containing complexes. This complex is thought to cleave TE antisense transcripts generating secondary piRNAs that are associated with MIWI2. MIWI 2 then cleaves TE sense transcripts producing new sense piRNAs that are again loaded into MILI.37,38 Additionally, both in Droshophila and mammals some piwi members may localize to the nucleus, but their nuclear function is not fully understood. Furthermore, there is a clear connection to DNA-methylation, as the mouse piRNA pathway is required for de novo DNA methylation and silencing of TEs in germ cells.37 Thus, it is thought that the combined action of DNA-methylation and piRNAs may control the accumulation of new TEs in germ cells of mammals. Indeed, most TE insertions in humans and mouse seem to be accumulated during early embryogenesis and new insertions in germ cells are rare.35,39,40

We have recently described that the Microprocessor, a nuclear protein complex involved in microRNA (miRNA) biogenesis, may act as a new post-transcriptional mechanism to control the mobilization of mammalian retrotransposons in the nucleus (Fig. 1, right side).41 During miRNA biogenesis, the Microprocessor recognizes and cleaves hairpin RNA structures embedded within the sequence of primary miRNA sequences (pri-miRNAs) in the nucleus.42-44 The minimal catalytically active Microprocessor is a heterodimer formed by the double-stranded RNA-binding protein, DGCR8 and the RNaseIII enzyme, Drosha. DGCR8 recognizes the pri-miRNA substrate whereas Drosha functions as the endonuclease generating precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) that are exported to the cytoplasm where they are further processed by another RNase III enzyme, Dicer (DCR), to generate mature miRNAs.42-44 A DGCR8 HITS-CLIP (high-throughput sequencing of RNA isolated by cross-linking immunoprecipitation) experiment designed to identify novel substrates of the Microprocessor revealed that this complex binds and regulates a large variety of cellular RNAs.45 The CLIP protocol is based on an UV irradiation step in order to induce covalent links between protein and RNA molecules present within a complex. In principle, this allows to conduct highly stringent immunoprecipitation and washing conditions so that only those RNAs directly bound to the protein of interest are selected (reviewed in refs. 46 and 47). To further assess the reproducibility of this approach, we compared endogenous DGCR8 HITS-CLIP reads with a replicate of the experiment using transiently transfected epitope-tagged DGCR8 protein (pCG T7-DGCR8). Notably, we observed a strong correlation between both experiments, which suggests that the identified DGCR8 targets are indeed specific targets.45 Interestingly, one third of the DGCR8 RNA targets corresponded to human repetitive sequences, including active TEs. We confirmed that DGCR8 recognizes and binds active retrotransposons (LINE-1, Alu and SVA) in human cultured cells and that the Microprocessor can process LINE-1 and Alu derived RNAs in vitro and likely in vivo. Notably, we also determined that the Microprocessor regulates the abundance of L1 mRNAs and encoded proteins both in human pluripotent cells as well as in DGCR8−/− mouse Embryonic Stem (mES) cells.41 Altogether, these data strongly suggest that the Microprocessor controls TE expression levels by processing their RNA derived transcripts. Importantly, we demonstrated that the Microprocessor negatively regulates Alu and LINE-1 engineered retrotransposition in cultured HeLa cells, most likely by binding and processing RNA derived from these TEs (Fig. 1).41 Furthermore, other transposable elements and even processed pseudogenes that require L1-encoded proteins for their mobilization might be indirectly regulated by the Microprocessor. In sum, these data suggest a function for the Microprocessor in restricting non-LTR retrotransposon mobilization; we further propose that this regulation might be relevant in somatic tissues, acting as a repressor of those active TE copies that escape transcriptional silencing.41 However, numerous questions remain to be answered. Notably, a high proportion of the reads from HITS-CLIP experiments mapped to transcripts derived from inactive TEs in humans, like mRNAs derived from evolutionary older LINE-1 subfamilies, LTR retrotransposons and even DNA-Transposons. That could reflect that this complex has acted in reducing the impact of TE mobilization through evolution. However, mutation accumulation over time and high error rates of reverse transcriptases encoded by LTR and non-LTR retrotransposons16,48 make it unlikely that pri-microRNA like structures have remained unchanged through evolution. Thus, we speculate that the binding and likely processing of RNAs derived from inactive TEs could also reflect a more generic function of the Microprocessor: destabilization of non-functional RNAs transcribed within cells. The HITS-CLIP approach also revealed that DGCR8 binds many other types of structured RNAs: several hundred mRNAs/pseudogenes and non-coding RNAs such as rRNAs, snRNAs, snoRNAs (small nucleolar RNAs) and lincRNAs (long intergenic non-coding RNAs).45,49 We confirmed the direct interaction of DGCR8 with several of those RNA targets (such as mRNAs, snoRNAs, lincRNAs as well as TEs) by immunoprecipitation/RT-qPCR experiments.41,45 Some of those RNAs could probably correspond to aberrant transcripts or non-functional transcripts that might be destabilized by the Microprocessor in the nucleus. Furthermore, this hypothesis could explain the identification of additional biding sites for DGCR8 in the antisense strand of RC-L1s, Alu and SVA derived RNA sequences, although we cannot rule out that they might have a role in TE biology or genome regulation.

An additional arising question is whether some TE-derived RNA products generated by the Microprocessor are further processed in the cytoplasm by Dicer (DCR) to generate mature and functional miRNAs. Indeed, previous bioinformatic analyses have shown that subsets of canonical mammalian miRNAs are derived from LINE-2 elements and other currently inactive genomic repeats.50 Notably miRNAs and small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are cleaved from short hairpin and double-stranded RNA precursors by DCR endonucleases and bound by Argonaute proteins (AGO) in a large multiprotein complex called RISC (Fig. 1). RISC then targets homologous sequences in cellular RNAs, inducing their degradation or suppressing their translation. Interestingly, a recent study that analyzed the repertoire of small RNAs (sRNAs) in cultured mES revealed a significant depletion of sense and antisense 5′UTR-L1-derived 22nt-sRNA in DCR−/− mES cells and qRT-PCR experiments showed that a fraction of them were specifically loaded in AGO2, as canonical microRNAs.51,52 Notably, miRNA or siRNA biogenesis pathways could generate these sRNAs. Interestingly, Ago2−/− and DCR−/− mES cells also exhibit increased levels of mouse L1 derived mRNAs. Ciaudo and colleagues attributed the activation of LINE-1 in those cells to the depletion of 5′UTR-L1 derived sRNA and proposed that RNAi may act to control retrotransposition in mES cells. Indeed, a model where the bidirectional transcription of opposed L1 retrotransposon sequences24,25 results in the formation of double-stranded RNAs processed to siRNAs that suppress retrotransposition by an RNA interference mechanism was previously suggested in human cells.53

Remarkably, it has been recently demonstrated that RNAi has an important function in immunity against viruses in mammals.54-56 This pathway seems to be active exclusively in stem cells (i.e., early embryogenesis) where the innate antiviral interferon (IFN) response is non functional.57,58 Indeed, Maillard and colleagues observed that upon infection of mES cells with encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) or Nodamura virus, virus-derived small RNAs (vsRNAs) were associated with AGO2, whereas they were undetectable in cells lacking Dicer and decreased upon cell differentiation.55 Furthermore, the infection of mES cells, hamster cells and suckling mice by Nodamura virus requires RNAi suppression by an inhibitor of Dicer encoded by the virus.55,56 Altogether, these data suggest that DCR recognizes and cleaves dsRNA in undifferentiated cells and further support that RNAi is an ancient form of immunity that evolved to suppress viruses and transposable elements during early embryogenesis (Fig. 1). Although heritable new TE insertions in humans may accumulate during early embryogenesis,35,39,40 recent studies have also uncovered a surprisingly load of somatic retrotransposition in selected tissues, mainly in the brain and in several type of tumors (recently reviewed in refs. 59 and 60). Thus, further studies are required to fully understand the contribution of RNA-derived mechanisms in the control of TE mobilization in cancer and the human brain.

DCR and the Microprocessor are involved in miRNA biogenesis. Most miRNAs interact with 3′UTRs of RNA targets inducing their degradation or suppressing their translation.61 Thus, and in order to test whether the control of L1 mobilization by the Microprocessor is mediated by miRNAs, we used engineered retrotransposition constructs lacking 3′UTR sequences. Importantly, a similar increase in retrotransposition was observed for the construct that lacks the 3′UTR upon Microprocessor depletion, strongly suggesting that the Microprocessor control of L1 mobilization seems to work in a DCR and miRNA independent manner.41 Supporting this hypothesis, luciferase-based reporters containing the 5′UTR of an active LINE-1 produced more reporter activity in the absence of the Microprocessor than in the absence of DCR.41 Altogether, these data suggest that the Microprocessor and DCR can independently regulate TE RNA levels and subsequent mobilization. Notably, other key factors that may have a role in the dynamic regulation of TE derived RNAs were further identified by Ciaudo et al., as depletion of nuclear Xrn2 and exosome co-factor Rrp6 led to the accumulation of L1 transcripts and L1-ORF1p, correlating with reduced levels of the most abundant sense and antisense L1-derived sRNAs51(Fig. 1). Additionally, previous studies have shown that the Microprocessor co-operates with Setx, Xrn2 and Rrp6 to induce the premature termination of transcription by RNA pol II at the HIV-1 promoter.62 The exosome complex is the major source of 3′→5′ ribonucleolytic activity in eukaryotic cells and exerts an indispensable role in RNA processing and quality control.63 Rrp6 is an RNase D-related 3′→5′ exoribonuclease that provide this activity to the nuclear exosome.64 Setx is the human homolog of the Sen1 protein in yeast, a RNA/DNA helicase contained in a complex involved in transcriptional termination of several classes of RNAs. Sen1-mediated termination of transcription is potentiated by a 5′ –3 exoribonuclease, Rat1p/Xrn2, that following cleavage, degrades the uncapped nascent transcript to promote the release of RNAPII from its template.65 Whether L1 mRNA destabilization by these RNA surveillance pathways is coordinated with Microprocessor-mediated processing remains to be seen.

In sum, data from different laboratories indicate that several RNA-mediated mechanisms act to control the expression and mobilization of TEs. Importantly, characterization of endogenous LINE-1 mobilization events in stem and somatic cells using the latest advances in high-throughput sequencing and single cell genomic is still required to unambiguously determine the real impact of the Microprocessor and other factors in retrotransposon control.52 In sum, these data suggest that several post-transcriptional mechanisms targeting mammalian retrotransposon derived mRNAs might simultaneously act in nucleus and cytoplasm to reduce their mutagenic potential (Fig. 1). These results further reveal the complex regulation of TEs within a host, and suggest that multiple mechanisms at different levels act to control the impact of TEs in genomes.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

SRH was supported by a Marie-Curie Intra-European Fellowship and a Marie Curie CIG-Grant (PCIG10-GA-2011-303812). SM was the recipient of a long-term EMBO postdoctoral fellowship. JFC is funded by Core funding from the Medical Research Council and by the Wellcome Trust (Grant 095518/Z/11/Z). JLGP lab is supported by FIS-FEDER-PI11/01489, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (IECS-55007420) and the European Research Council (ERC-Consolidator Grant “EPIPLURIRETRO-309433”).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- TE

transposable element

- LINE- 1 or L1

long interspersed element

- RC-L1

retrocompetent L1

- SINE

short interspersed element

- LTR

long terminal repeat

- UTR

untranslated region

- ORF

open reading frame

- DGCR8

DiGeorge syndrome critical region 8 gene

- mES cells

mouse embryonic stem cells

- sRNAs

small RNAs

- siRNAs

small-interfering RNAs

- RNAi

RNA interference

- piRNAs

piwi-interacting RNAs

- AGO

argonaute

- miRNA

microRNA

- DCR

Dicer

References

- 1.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, et al. International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kazazian HH., Jr. Mobile elements: drivers of genome evolution. Science. 2004;303:1626–32. doi: 10.1126/science.1089670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills RE, Bennett EA, Iskow RC, Devine SE. Which transposable elements are active in the human genome? Trends Genet. 2007;23:183–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck CR, Collier P, Macfarlane C, Malig M, Kidd JM, Eichler EE, Badge RM, Moran JV. LINE-1 retrotransposition activity in human genomes. Cell. 2010;141:1159–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brouha B, Schustak J, Badge RM, Lutz-Prigge S, Farley AH, Moran JV, Kazazian HH., Jr. Hot L1s account for the bulk of retrotransposition in the human population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5280–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0831042100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dewannieux M, Esnault C, Heidmann T. LINE-mediated retrotransposition of marked Alu sequences. Nat Genet. 2003;35:41–8. doi: 10.1038/ng1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jurka J. Sequence patterns indicate an enzymatic involvement in integration of mammalian retroposons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1872–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ostertag EM, Goodier JL, Zhang Y, Kazazian HH., Jr. SVA elements are nonautonomous retrotransposons that cause disease in humans. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:1444–51. doi: 10.1086/380207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodier JL, Kazazian HH., Jr. Retrotransposons revisited: the restraint and rehabilitation of parasites. Cell. 2008;135:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moran JV, Gilbert N. Mammalian LINE-1 retrotransposons and related elements. In: Craig N, Craggie R, Gellert M, Lambowitz A, eds. Mobile DNA II. Washington, DC: ASM Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esnault C, Maestre J, Heidmann T. Human LINE retrotransposons generate processed pseudogenes. Nat Genet. 2000;24:363–7. doi: 10.1038/74184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei W, Gilbert N, Ooi SL, Lawler JF, Ostertag EM, Kazazian HH, Boeke JD, Moran JV. Human L1 retrotransposition: cis preference versus trans complementation. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1429–39. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1429-1439.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Z, Carriero N, Gerstein M. Comparative analysis of processed pseudogenes in the mouse and human genomes. Trends Genet. 2004;20:62–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buzdin A, Ustyugova S, Gogvadze E, Vinogradova T, Lebedev Y, Sverdlov E. A new family of chimeric retrotranscripts formed by a full copy of U6 small nuclear RNA fused to the 3′ terminus of l1. Genomics. 2002;80:402–6. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Perez JL, Doucet AJ, Bucheton A, Moran JV, Gilbert N. Distinct mechanisms for trans-mediated mobilization of cellular RNAs by the LINE-1 reverse transcriptase. Genome Res. 2007;17:602–11. doi: 10.1101/gr.5870107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert N, Lutz S, Morrish TA, Moran JV. Multiple fates of L1 retrotransposition intermediates in cultured human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7780–95. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.17.7780-7795.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kazazian HH., Jr. Genetics. L1 retrotransposons shape the mammalian genome. Science. 2000;289:1152–3. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hohjoh H, Singer MF. Sequence-specific single-strand RNA binding protein encoded by the human LINE-1 retrotransposon. EMBO J. 1997;16:6034–43. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.19.6034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin SL, Bushman FD. Nucleic acid chaperone activity of the ORF1 protein from the mouse LINE-1 retrotransposon. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:467–75. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.2.467-475.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng Q, Moran JV, Kazazian HH, Jr., Boeke JD. Human L1 retrotransposon encodes a conserved endonuclease required for retrotransposition. Cell. 1996;87:905–16. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81997-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathias SL, Scott AF, Kazazian HH, Jr., Boeke JD, Gabriel A. Reverse transcriptase encoded by a human transposable element. Science. 1991;254:1808–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1722352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moran JV, Holmes SE, Naas TP, DeBerardinis RJ, Boeke JD, Kazazian HH., Jr. High frequency retrotransposition in cultured mammalian cells. Cell. 1996;87:917–27. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81998-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swergold GD. Identification, characterization, and cell specificity of a human LINE-1 promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:6718–29. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macia A, Muñoz-Lopez M, Cortes JL, Hastings RK, Morell S, Lucena-Aguilar G, Marchal JA, Badge RM, Garcia-Perez JL. Epigenetic control of retrotransposon expression in human embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:300–16. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00561-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Speek M. Antisense promoter of human L1 retrotransposon drives transcription of adjacent cellular genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1973–85. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.6.1973-1985.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alisch RS, Garcia-Perez JL, Muotri AR, Gage FH, Moran JV. Unconventional translation of mammalian LINE-1 retrotransposons. Genes Dev. 2006;20:210–24. doi: 10.1101/gad.1380406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dmitriev SE, Andreev DE, Terenin IM, Olovnikov IA, Prassolov VS, Merrick WC, Shatsky IN. Efficient translation initiation directed by the 900-nucleotide-long and GC-rich 5′ untranslated region of the human retrotransposon LINE-1 mRNA is strictly cap dependent rather than internal ribosome entry site mediated. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4685–97. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02138-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doucet AJ, Hulme AE, Sahinovic E, Kulpa DA, Moldovan JB, Kopera HC, Athanikar JN, Hasnaoui M, Bucheton A, Moran JV, et al. Characterization of LINE-1 ribonucleoprotein particles. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hohjoh H, Singer MF. Cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein complexes containing human LINE-1 protein and RNA. EMBO J. 1996;15:630–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kulpa DA, Moran JV. Ribonucleoprotein particle formation is necessary but not sufficient for LINE-1 retrotransposition. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3237–48. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hancks DC, Kazazian HH., Jr. Active human retrotransposons: variation and disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoder JA, Walsh CP, Bestor TH. Cytosine methylation and the ecology of intragenomic parasites. Trends Genet. 1997;13:335–40. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(97)01181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bourc’his D, Bestor TH. Meiotic catastrophe and retrotransposon reactivation in male germ cells lacking Dnmt3L. Nature. 2004;431:96–9. doi: 10.1038/nature02886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muñoz-Lopez M, Macia A, Garcia-Cañadas M, Badge RM, Garcia-Perez JL. An epi [c] genetic battle: LINE-1 retrotransposons and intragenomic conflict in humans. Mob Genet Elements. 2011;1:122–7. doi: 10.4161/mge.1.2.16730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levin HL, Moran JV. Dynamic interactions between transposable elements and their hosts. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:615–27. doi: 10.1038/nrg3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siomi MC, Sato K, Pezic D, Aravin AA. PIWI-interacting small RNAs: the vanguard of genome defence. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:246–58. doi: 10.1038/nrm3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aravin AA, Sachidanandam R, Bourc’his D, Schaefer C, Pezic D, Toth KF, Bestor T, Hannon GJ. A piRNA pathway primed by individual transposons is linked to de novo DNA methylation in mice. Mol Cell. 2008;31:785–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li C, Vagin VV, Lee S, Xu J, Ma S, Xi H, Seitz H, Horwich MD, Syrzycka M, Honda BM, et al. Collapse of germline piRNAs in the absence of Argonaute3 reveals somatic piRNAs in flies. Cell. 2009;137:509–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia-Perez JL, Marchetto MC, Muotri AR, Coufal NG, Gage FH, O’Shea KS, Moran JV. LINE-1 retrotransposition in human embryonic stem cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1569–77. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kano H, Godoy I, Courtney C, Vetter MR, Gerton GL, Ostertag EM, Kazazian HH., Jr. L1 retrotransposition occurs mainly in embryogenesis and creates somatic mosaicism. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1303–12. doi: 10.1101/gad.1803909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heras SR, Macias S, Plass M, Fernandez N, Cano D, Eyras E, Garcia-Perez JL, Cáceres JF. The Microprocessor controls the activity of mammalian retrotransposons. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:1173–81. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Denli AM, Tops BB, Plasterk RH, Ketting RF, Hannon GJ. Processing of primary microRNAs by the Microprocessor complex. Nature. 2004;432:231–5. doi: 10.1038/nature03049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gregory RI, Yan KP, Amuthan G, Chendrimada T, Doratotaj B, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. The Microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature. 2004;432:235–40. doi: 10.1038/nature03120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Kim YK, Jin H, Kim VN. The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3016–27. doi: 10.1101/gad.1262504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Macias S, Plass M, Stajuda A, Michlewski G, Eyras E, Cáceres JF. DGCR8 HITS-CLIP reveals novel functions for the Microprocessor. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:760–6. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Licatalosi DD, Darnell RB. RNA processing and its regulation: global insights into biological networks. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:75–87. doi: 10.1038/nrg2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ule J, Jensen K, Mele A, Darnell RB. CLIP: a method for identifying protein-RNA interaction sites in living cells. Methods. 2005;37:376–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katz RA, Skalka AM. Generation of diversity in retroviruses. Annu Rev Genet. 1990;24:409–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.24.120190.002205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macias S, Cordiner RA, Cáceres JF. Cellular functions of the microprocessor. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:838–43. doi: 10.1042/BST20130011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smalheiser NR, Torvik VI. Mammalian microRNAs derived from genomic repeats. Trends Genet. 2005;21:322–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ciaudo C, Jay F, Okamoto I, Chen CJ, Sarazin A, Servant N, Barillot E, Heard E, Voinnet O. RNAi-dependent and independent control of LINE1 accumulation and mobility in mouse embryonic stem cells. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 52.Faulkner GJ. Retrotransposon silencing during embryogenesis: dicer cuts in LINE. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang N, Kazazian HH., Jr. L1 retrotransposition is suppressed by endogenously encoded small interfering RNAs in human cultured cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:763–71. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sagan SM, Sarnow P. Molecular biology. RNAi, Antiviral after all. Science. 2013;342:207–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1245475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maillard PV, Ciaudo C, Marchais A, Li Y, Jay F, Ding SW, Voinnet O. Antiviral RNA interference in mammalian cells. Science. 2013;342:235–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1241930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li Y, Lu J, Han Y, Fan X, Ding SW. RNA interference functions as an antiviral immunity mechanism in mammals. Science. 2013;342:231–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1241911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Billy E, Brondani V, Zhang H, Müller U, Filipowicz W. Specific interference with gene expression induced by long, double-stranded RNA in mouse embryonal teratocarcinoma cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14428–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261562698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paddison PJ, Caudy AA, Hannon GJ. Stable suppression of gene expression by RNAi in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1443–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032652399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singer T, McConnell MJ, Marchetto MC, Coufal NG, Gage FH. LINE-1 retrotransposons: mediators of somatic variation in neuronal genomes? Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:345–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carreira PE, Richardson SR, Faulkner GJ. L1 retrotransposons, cancer stem cells and oncogenesis. FEBS J. 2014;281:63–73. doi: 10.1111/febs.12601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:522–31. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wagschal A, Rousset E, Basavarajaiah P, Contreras X, Harwig A, Laurent-Chabalier S, Nakamura M, Chen X, Zhang K, Meziane O, et al. Microprocessor, Setx, Xrn2, and Rrp6 co-operate to induce premature termination of transcription by RNAPII. Cell. 2012;150:1147–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mitchell P, Petfalski E, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Tollervey D. The exosome: a conserved eukaryotic RNA processing complex containing multiple 3′-->5′ exoribonucleases. Cell. 1997;91:457–66. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80432-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burkard KT, Butler JS. A nuclear 3′-5′ exonuclease involved in mRNA degradation interacts with Poly(A) polymerase and the hnRNA protein Npl3p. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:604–16. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.2.604-616.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kawauchi J, Mischo H, Braglia P, Rondon A, Proudfoot NJ. Budding yeast RNA polymerases I and II employ parallel mechanisms of transcriptional termination. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1082–92. doi: 10.1101/gad.463408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]