Abstract

Background

Members of the ancient land-plant-specific transcription factor AT-Hook Motif Nuclear Localized (AHL) gene family regulate various biological processes. However, the relationships among the AHL genes, as well as their evolutionary history, still remain unexplored.

Results

We analyzed over 500 AHL genes from 19 land plant species, ranging from the early diverging Physcomitrella patens and Selaginella to a variety of monocot and dicot flowering plants. We classified the AHL proteins into three types (Type-I/-II/-III) based on the number and composition of their functional domains, the AT-hook motif(s) and PPC domain. We further inferred their phylogenies via Bayesian inference analysis and predicted gene gain/loss events throughout their diversification. Our analyses suggested that the AHL gene family emerged in embryophytes and further evolved into two distinct clades, with Type-I AHLs forming one clade (Clade-A), and the other two types together diversifying in another (Clade-B). The two AHL clades likely diverged before the separation of Physcomitrella patens from the vascular plant lineage. In angiosperms, Clade-A AHLs expanded into 5 subfamilies; while, the ones in Clade-B expanded into 4 subfamilies. Examination of their expression patterns suggests that the AHLs within each clade share similar expression patterns with each other; however, AHLs in one monophyletic clade exhibit distinct expression patterns from the ones in the other clade. Over-expression of a Glycine max AHL PPC domain in Arabidopsis thaliana recapitulates the phenotype observed when over-expressing its Arabidopsis thaliana counterpart. This result suggests that the AHL genes from different land plant species may share conserved functions in regulating plant growth and development. Our study further suggests that such functional conservation may be due to conserved physical interactions among the PPC domains of AHL proteins.

Conclusions

Our analyses reveal a possible evolutionary scenario for the AHL gene family in land plants, which will facilitate the design of new studies probing their biological functions. Manipulating the AHL genes has been suggested to have tremendous effects in agriculture through increased seedling establishment, enhanced plant biomass and improved plant immunity. The information gleaned from this study, in turn, has the potential to be utilized to further improve crop production.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12870-014-0266-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: AT-hook motif, AT-Hook Motif Nuclear Localized (AHL) genes, Diversification, PPC domain, Phylogeny

Background

Genes that regulated essential biological processes in ancient plant species constituted a conserved “gene tool kit”, which tended to be preserved throughout evolution [1-4]. Most of the members in this “tool kit” have generally duplicated and expanded into multi-member-containing gene families with divergent functions in modern land plants [1,5,6]. Understanding their functions as well as evolutionary histories have greatly enhanced our knowledge of plant growth and development, such as the cases of the cytochrome P450s [7], MADS-box transcription factors [8-12], AP2/EREBP genes [13-16], the TALE homeobox gene family [17-19], NAC transcription factors [20-22], HD-ZIP genes [23-25], Basic/Helix-Loop-Helix genes [26-28] and the TCP gene family [29-31].

However, there are also many gene families that are important to land plant evolution whose functions and evolutionary histories are not well understood. The ancient transcription factor AT-Hook Motif Nuclear Localized (AHL) gene family has been found in all sequenced plant species, ranging from the moss Physcomitrella patens, to flowering plants, such as Arabidopsis thaliana, Sorghum bicolor, Zea mays and Populus trichocarpa. High conservation of this gene family throughout land plant evolution suggests that it is important for plant growth and development. Currently we are beginning to understand the biological functions of several AHLs. The evolutionary history of this gene family, however, has still barely been explored.

Members of the AHL proteins contain two conserved structural units, the AT-hook motif and the Plant and Prokaryote Conserved (PPC) domain, the latter being also annotated as the Domain of Unknown Function #296 (DUF296) [32]. Since the functions of this domain have been partially revealed [33], hereafter, we will refer it only as the PPC domain. The AT-hook motif enables binding to AT-rich DNA and has been identified in various gene families both in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, including the High Mobility Group A (HMGA) proteins in mammals [34]. The AT-hook motif uses a conserved palindromic core sequence, Arg-Gly-Arg, to bind to the minor groove of AT-rich B-form DNA. Upon binding with DNA, this core sequence adopts a concave conformation with close proximity to the backbone of the DNA, with both arginine side chains firmly inserting into the minor groove [35].

The second functional unit of the AHL proteins is the PPC domain, which is approximately 120 amino acids in length and exists as a single protein in Bacteria and Archaea [32]. Crystal structures of several bacterial and archaeal PPC proteins suggested that the prokaryotic PPC proteins form a trimer [36,37]. In land plants, the PPC domain has been identified in AHL proteins where it is located at the carboxyl end relative to the AT-hook motif(s) [32]. The PPC domain is responsible for the nuclear localization of the AHL proteins as well as protein-protein interactions among AHL proteins and with other common interactors, such as transcription factors. It may suggest a role in regulating transcriptional activation by the AHL proteins in plants [33].

Members of the AHL family regulate diverse aspects of growth and development in plants. Most of the studies are from the analyses of Arabidopsis thaliana. Several AHLs are suggested to regulate the homeostasis of phytohormones, especially gibberellins [38], jasmonic acid [39] and cytokinins [40]. Two members of the Arabidopsis thaliana AHL gene family, SUPPRESSOR OF PHYTOCHROME B-4 #3 (SOB3/AHL29) and ESCAROLA (ESC/AHL27), repress hypocotyl elongation for seedlings grown in the light [41]. As adults, the AtAHL over-expression plants develop enlarged organs, such as expanded leaves, flowers and fruits as well as delayed flowering and senescence [41]. Similar functions have also been proposed for AtAHL22, and HERCULES (HRC/AHL25) [42,43]. Arabidopsis thaliana ESC/AtAHL27 and AHL20 have also been implicated in the regulation of plant defense responses [44,45].

In this study, we identified members of the AHL gene family in the completely sequenced genomes of 19 land plant species, ranging from the moss Physcomitrella patens and the lycophyte Selaginella to a variety of monocot and dicot species in the Phytozome database [46]. A closer look at their protein sequences revealed that these land plant AHL proteins can be divided into three types (Type-I, −II and -III) based on a combination of the number and composition of its two structural units, the AT-hook motif(s) and the PPC domain. The Type-I AHLs form one clade; while the Type-II and -III AHLs together form a separate clade. Phylogenetic analysis of the AHL genes in basal plants suggests that such divergence between the two clades dated between the appearance of chlorophytes and mosses. In this study, we have further identified that the AHL gene family in land plants evolved into 9 phylogenetic sub-families. Finally, we have proposed an evolutionary scenario for the AHL gene family in land plants.

Results

Early divergence in the land-plant AHL protein family

Members of the AHL gene family contain two functional units, the AT-hook motif and the PPC domain [32]. In order to identify the AHL genes in land plant species, we performed searches against the Phytozome database using the AHL nucleotide and amino acid sequences from Arabidopsis thaliana [46]. We further added the retrieved results as additional queries to perform further searches to identify AHL genes from the genomes of 19 plant species (Figure 1a, Additional files 1, 2 and 3).

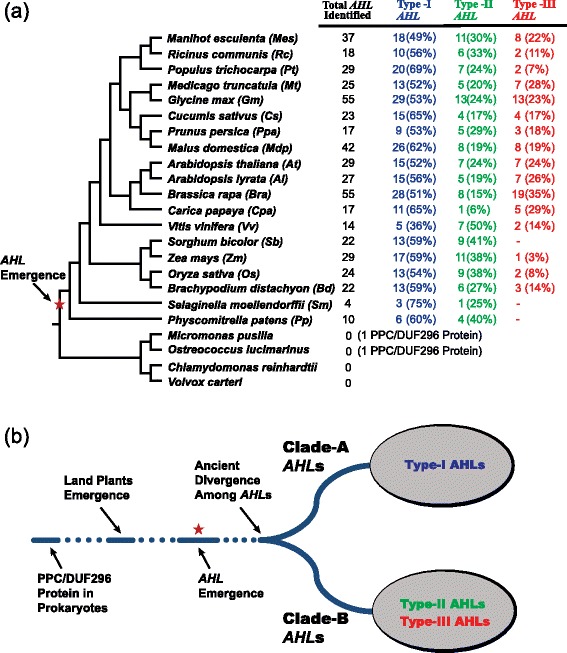

Figure 1.

AHL genes identified in land plant species. (a) The numbers of the AHL genes identified in each sequenced plant genome were listed accordingly. The percentages of each type were also listed in parenthesis. (b) AHL genes emerged in land plant species and further diverged into two separate monophyletic clades (Clade-A and Clade-B). The red star denoted the time point when the AHL genes are likely to have emerged.

Initial phylogenetic analysis of the retrieved AHL proteins in this study suggested that all of the land-plant AHL proteins evolved into two major clades (Figure 1b). This distinct division into two monophyletic clades could also be observed in phylogenetic analysis when using just the AHL genes from Arabidopsis thaliana [32,33,38,41] and Oryza sativa [47]. Analysis of all the AHL genes identified in this study in the moss and lycophytes reveals a similar distribution into these two clades. This further suggests that the division between these two branches dated before the divergence of mosses from the rest of the land plants.

Each monophyletic clade defines one type of PPC domain in land plant AHL proteins

Examination of the PPC domains revealed that their protein sequences share unique characteristics within each of the two AHL phylogenetic clades (Figure 1b, Additional file 4). The Clade-A AHL proteins share the same type of PPC domain (hereby named “Type-A PPC domain”). Clade-B AHL proteins share another type of PPC domain (hereby named “Type-B PPC domain”).

In order to further examine the divergence between the PPC domains in AHL proteins, we performed a sequence logo analysis. The Type-A PPC Domain in Clade-A generally starts with Leu-Arg-Ser-His (Additional file 4a); while the Type-B PPC domain in Clade-B generally starts with Phe-Thr-Pro-His (Additional file 4b). Both types of PPC domains in AHL proteins are further followed by stretches of amino acid residues with moderate conservation. Examination of both types of PPC domains in the identified AHL proteins revealed that they contain a consensus conserved Gly-Arg-Phe-Glu-Ile-Leu motif (Additional file 4a, b). It is also interesting to note that the coding sequences of this motif always exists at the immediate beginning of one exon region in the intron-containing Type-B PPC/DUC296 domains. The sequence upstream of the conserved six amino acids in Type-B PPC domains is generally Thr-Tyr-Glu, while it is generally Thr-Lys-His upstream of the six amino acids in Type-A PPC domains. The sequences downstream of the conserved six amino acids in both types of PPC domains are similar to each other.

Conserved functions of PPC domains in AHL proteins in land plants

In order to understand the biological functions of the PPC domains in the AHL proteins, we cloned two full-length AHL genes from the bread wheat Triticum aestivum and one PPC domain from a soybean Glycine max AHL gene (Gm06g01650.1) (Additional file 5). Although Gm06g01650.1 is only a partial gene, it together with the cloned wheat AHLs and two Arabidopsis thaliana AHLs encode proteins that all contain a Type-I AT-hook motif and a Type-A PPC domain (Additional files 5 and 6). They share the same arrangement of secondary structural elements and tertiary structures with each other, as well as with their counterparts in prokaryotes and the moss, Physcomitrella patens (Figure 2a and 2b). A careful examination reveals that their PPC domains all exhibit a β1-α-β3-β7-β4-β5-β6-β2 secondary structural arrangement, suggesting possible conserved biological functions of this domain among multiple species.

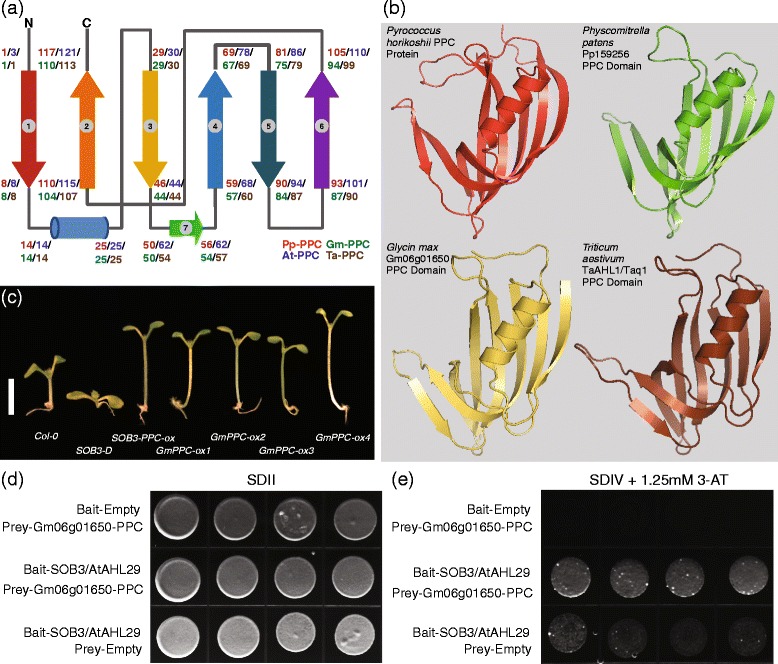

Figure 2.

The AHL proteins comprise AT-hook motif(s) and PPC domain. (a) Topology of secondary structures of the AHL PPC domains from multiple land plant species. The cylinder denotes an α-helix and the arrows denote β-sheets. The numbers represent positions of the amino acids in the AHL PPC domain at the corresponding secondary structure positions. Pp-PPC, Pp159256 PPC domain. At-PPC, AtAHL29 PPC domain. Gm-PPC, Gm06g01650.1 PPC domain. Ta-PPC, TaAHL1 PPC domain. (b) Predicted tertiary structures of the PPC domains from these AHL proteins. (c) Hypocotyl growth of Col-0, SOB3-D, SOB3-PPC overexpression and multiple Gm06g01650-PPC overexpression lines, growing in 20 μmol∙s−1∙m−2 white light. Scale bar = 5 mm. (d and e) Full length Arabidopsis thaliana SOB3/AtAHL29 interacts with the PPC domain of Glycine max Gm06g01650.1 in an yeast two-hybrid assay.

To test the hypothesis that the PPC domain may share conserved biological regulatory functions, we overexpressed this domain from Gm06g01650.1 driven by the 35S constitutive promoter in wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana. Multiple homozygous over-expression lines containing single-locus insertions exhibited longer hypocotyls in white light comparing with wild-type controls (Figure 2c). This long-hypocotyl phenotype is similar to the one demonstrated by seedlings over-expressing the PPC domain from Arabidopsis thaliana AtAHL29/SOB3 [33], suggesting that shared conserved biological functions exist between Glycine max and Arabidopsis thaliana AHLs.

Arabidopsis thaliana AHLs have been suggested to suppress hypocotyl growth in the light [33,41]. Therefore, the long-hypocotyl phenotype exhibited by over-expressing the Gm06g01650.1 PPC domain may be conferred through the disturbance of the growth suppression roles of Arabidopsis thaliana AHL genes. To test this hypothesis, we examined if the PPC domain of Gm06g01650.1 can physically interact with the Arabidopsis thaliana AHL proteins using a targeted lexA-based yeast two-hybrid assay (Figure 2d,e). Using 1.25 mM 3-amino-1, 2, 4-triazol that prevented transcriptional auto-activation by SOB3/AtAHL29 in the bait protein, we demonstrated that SOB3/AtAHL29 from Arabidopsis thaliana and the PPC domain of Glycine max Gm06g01650.1 can interact with each other (Figure 2d,e).

Type-I and -II AT-hook motifs exist in AHL proteins

Two types of AT-hook motifs (Type-I and -II) are found in the AHL proteins (Figure 3a,b; Additional file 7) [33,34]. Both types of AT-hook motifs in the AHL proteins share the same conserved Arg-Gly-Arg core and use this conserved palindromic core to bind the minor groove of AT-rich B-form DNA [35]. Clade-A AHLs contain only one copy of the Type-I AT-hook motifs; while, in Clade-B, some of the AHLs contain only one copy of the Type-II AT-hook motifs and the rest contain both types of AT-hook motifs.

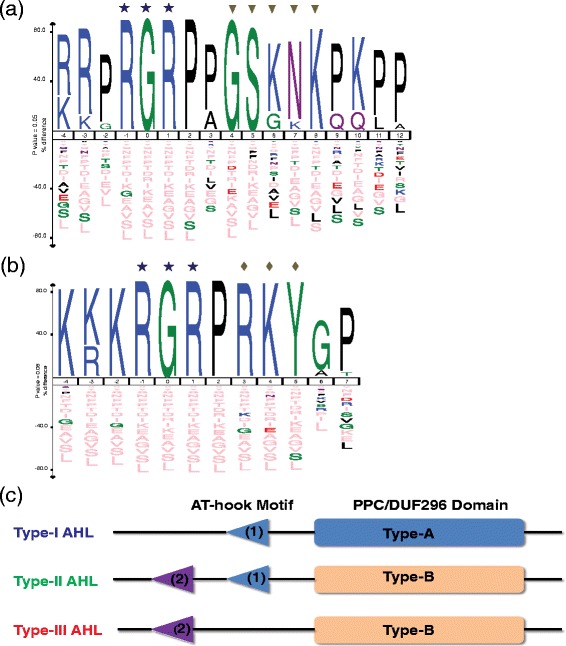

Figure 3.

Type of AHL proteins and their AT-hook motifs in land plants. Ice-Logo analysis of the Type-I AT-hook motifs (a) and Type-II AT-hook motifs (b) in land-plant AHL proteins. The star symbol denotes the core sequence of the AT-hook motif. The conserved sequence downstream of the core sequences in Type-I and Type-II AT-hook motifs were pointed out by the triangle and diamond symbols accordingly. (c) Topology of three types of AHL proteins identified in land plants based on the combination of AT-hook motifs and PPC domain.

A specific consensus sequence, Gly-Ser-Lys-Asn-Lys, was observed at the carboxyl end of the Arg-Gly-Arg core sequence in the Type-I AT-hook motifs (Figure 3a, Additional file 7a,b). The conservation of these downstream sequences is more significant in the AHLs that only contain this type of AT-hook motif. However, these sequences are more variable in other AHLs that also possess a Type-II AT-hook motif (Additional file 7b). Only short consensus amino acid stretches, Arg-Lys-Tyr, could be observed downstream of the conserved Arg-Gly-Arg core sequences of the Type-II AT-hook motifs in clades of both AHLs (Figure 3b, Additional file 7c,d). The conservation of these downstream sequences is similar among the AHLs in either clade (Additional file 7c,d).

Three types of AHL proteins in land plants

Based on a combination of type and number of the AT-hook motif(s) and the PPC domain, all the AHL proteins identified in this study can be further classified into three types (Type-I, −II and -III AHLs) (Figure 3c). The Type-I AHL proteins contain one Type-I AT-hook motif and one Type-A PPC domain. The Type-II AHL proteins contain two AT-hook motifs (one additional Type-II AT-hook motif at the N-terminus of the Type-I AT-hook motif) and one Type-B PPC domain. Finally, the Type-III AHL proteins contain one Type-II AT-hook motif and one Type-B PPC domain. Clade-A is comprised of the Type-I AHL genes, while Clade-B is comprised of the Type-II and -III AHL genes. Both clades have AHL genes from Physcomitrella patens (moss) forming a sister clade to the rest of the members of the clade, indicating an early divergence between the Type-I AHLs and the other two types of AHL genes.

Type-I and -II AHLs found in flowering plants were present in early-diverged land plants

In order to understand the evolutionary origin of the AHL genes, we also performed searches for AHL genes in chlorophytes. Neither any AHL genes nor genes encoding the PPC domain could be identified in the current release of the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Volvox carteri genomes (Figure 1a) [46,48,49]. Surprisingly, we were able to identify only one PPC gene that encodes only the PPC domain without an associated AT-hook motif(s) in Micromonas pusilla CCMP1545 [50] and Ostreococcus lucimarinus [51] (Additional file 8). To further examine the presence of the PPC gene in picoeukaryotic species, we further examined the genome of an additional picoeukaryotic strain Ostreococcus tauri [52]. Similarly, only a single copy of the PPC gene could be identified (Additional file 8). This is similar to the case observed in bacterial and archaeal genomes, where each species contains only one PPC gene which encodes a single protein (Additional file 8) [32].

We further examined the genomic sequences of the AHL genes and found that the Type-II and -III AHL genes generally contain introns, while the Type-I AHL genes lack introns in their genomic sequences. This suggests that it is likely that the intron-less Type-I AHL genes in land plants is the ancestral form from which the two intron-containing types are derived. In each species, there are generally more Type-I AHL genes in number than either of the other two types (Figure 1a). Compared to other families, the Poaceae species have a lower percentage of Type-III AHL genes, including Zea mays [53], Oryza sativa [54,55] and Brachypodium distachyon [56]. Notably, in Sorghum bicolor [57] we could not detect any Type-III AHLs (Figure 1a). It is likely that the Type-III AHLs arose latest since the moss Physcomitrella patens and lycophyte Selaginella moellendorffii contain only Type-I and -II AHLs (Figure 1a).

Plant introns have been suggested to play important roles in regulating the expression of their associated genes through alternative splicing [58-60], nonsense-mediated mRNA decay [61], or intron-mediated transcriptional enhancement [62]. In order to understand the biological functions of the introns in Type-II and -III AHLs, we extracted the intron sequences from Arabidopsis thaliana AHLs and examined their capabilities to enhance the transcription of their associated genes using the IMEter 2.0 server [63]. The first introns of several AtAHLs demonstrated at least a moderate ability to enhance the transcription of their genes (Additional file 9a-c). Particularly, the first introns in AtAHL4, 6 and 14 are predicted to strongly enhance their transcription.

Monophyletic Clade-A contains type-I AHLs

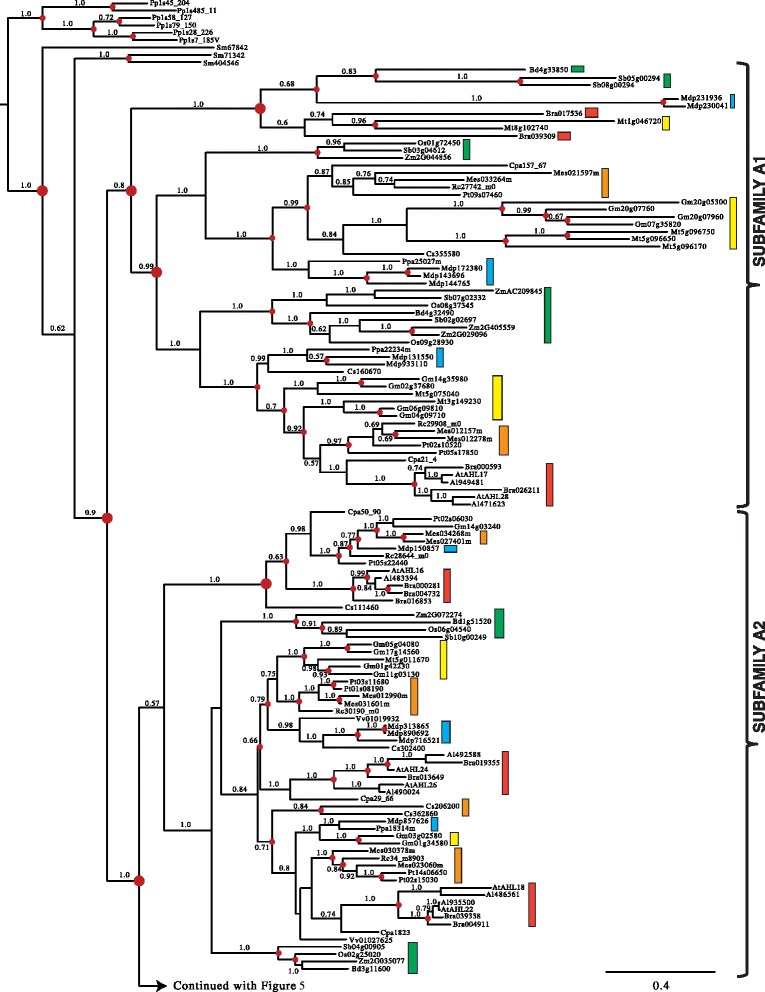

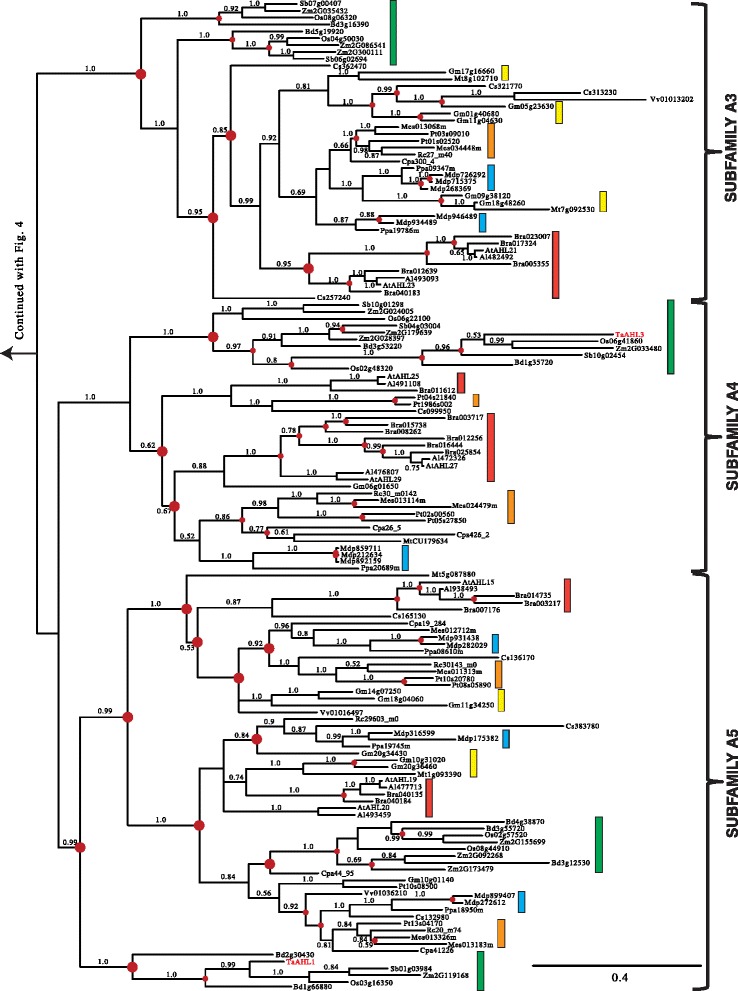

The early divergence between and significant divergence within the two AHL clades made analyzing them separately necessary to obtain reliable amino acid alignments. We first performed Bayesian inference analysis on the retrieved Clade-A AHLs. The Clade-A AHLs in land plants is comprised of Type-I AHLs that we have organized for discussion convenience into five subfamilies (Subfamilies A1, A2, A3, A4 and A5) (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Phylogeny of the Clade-A AHL gene family in land plants using Bayesian analysis. Clade-A AHLs are separated into 5 subfamilies (A1, A2, A3, A4 and A5). Two AHL genes (TaAHL1 and TaAHL3) were cloned from Triticum aestivum and shown in red. Green boxes represent AHL genes from Poaceae, yellow boxes denote genes from Fabaceae, blue boxes denote genes from Rosaceae, orange boxes denote genes from Malpighiales, and red boxes denote genes from Brassicaceae. Numbers near the branches indicate the Bayesian posterior probabilities for given clades. The red dots at internal nodes denote where gene duplication events have occurred.

Figure 5.

Phylogeny of the Clade-A AHL gene family in land plants using Bayesian analysis. Clade-A AHLs are separated into 5 subfamilies (A1, A2, A3, A4 and A5). Two AHL genes (TaAHL1 and TaAHL3) were cloned from Triticum aestivum and shown in red. Green boxes represent AHL genes from Poaceae, yellow boxes denote genes from Fabaceae, blue boxes denote genes from Rosaceae, orange boxes denote genes from Malpighiales, and red boxes denote genes from Brassicaceae. Numbers near the branches indicate the Bayesian posterior probabilities for given clades. The red dots at internal nodes denote where gene duplication events have occurred.

In order to better understand the evolutionary events which occurred among these five subfamilies, we reconciled the obtained Bayesian tree with the land-plant species tree and inferred whether the internal nodes within the Clade-A Bayesian tree were associated with gene duplication, gene loss, or lineage divergence events. Since their emergence in land plants, the AHLs within this clade have undergone multiple gene duplication events in the early plant lineages. The Subfamily A1-A5 AHLs emerged from lineage divergence events after the divergence of lycophyte AHLs and from the rest of vascular plants and further expanded via a series of gene-duplication/divergence events in angiosperms. The emergence of Subfamily A1, A3 and A5 AHLs started via gene-duplication events; while, Subfamily A2 and A4 AHLs emerged via speciation events.

Within each subfamily of Clade A, AHL genes from Euphorbiaceae, Salicaceae, Fabaceae, Rosaceae, Brassicaceae and Poaceae families could all be observed, suggesting they may have evolved from one subfamily-specific most common ancestral gene and later functional divergence occurred among these subfamilies. In the extant plant species, the AHL genes have undergone extensive gene-duplication/loss events (Table 1). The gene duplication events in several extant plant species, such as Glycine max [64] and Malus domestica [65], are probably associated with their recent whole genome duplication events. On the contrary, in several other plant species including Ricinus communis, Carica papaya, Vitis vinifera and monocot species, the AHL gene phylogenies show drastic gene loss events.

Table 1.

Numbers of gene duplication and loss event of the AHL genes in extant land plant species

| Extant land plant species | Clade-A AHL s (Type-I) | Clade-B AHL s (Types-II/-III) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of gene duplication | No. of gene loss | No. of gene duplication | No. of gene loss | |

| Manihot esculenta (Mes) | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Ricinus communis (Rc) | 0 | 7 | 0 | 10 |

| Populus trichocarpa (Pt) | 6 | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| Medicago truncatula (Mt) | 3 | 10 | 2 | 5 |

| Glycine max (Gm) | 12 | 3 | 13 | 2 |

| Cucumis sativus (Cs) | 1 | 8 | 0 | 7 |

| Prunus persica (Ppa) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Malus domestica (Mdp) | 13 | 0 | 7 | 2 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana (At) | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Arabidopsis lyrata (Al) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Brassica rapa (Bra) | 3 | 7 | 4 | 2 |

| Carica papaya (Cpa) | 0 | 8 | 0 | 6 |

| Vitis vinifera (Vv) | 0 | 20 | 0 | 16 |

| Sorghum bicolor (Sb) | 1 | 9 | 0 | 3 |

| Zea mays (Zm) | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Oryza sativa (Os) | 0 | 12 | 0 | 5 |

| Brachypodium distachyon (Bd) | 0 | 12 | 1 | 8 |

| Selaginella moellendorffii (Sm) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Physcomitrella patens (Pp) | 5 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

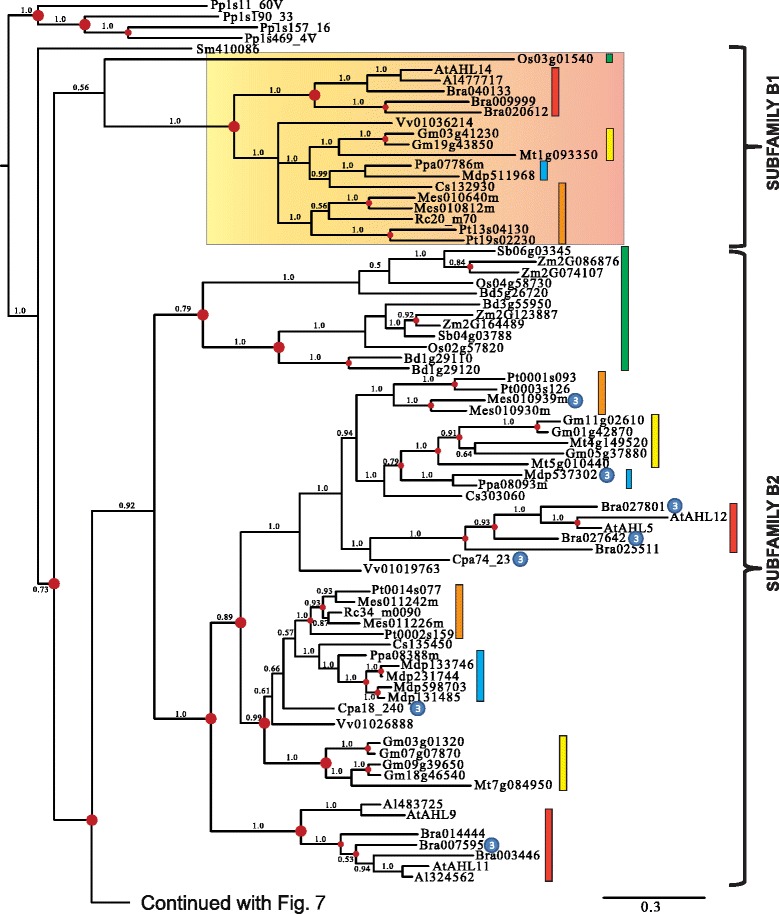

Monophyletic Clade-B contains type-II and -III AHLs

Clade-B of the AHL gene family is comprised of Type-II and Type-III AHLs (Figures 6 and 7). The Type-II AHLs from the early diverging moss Physcomitrella patens and lycophyte Selaginella moellendorffii constitute a clade at the base of the phylogenetic tree (Figure 6). The angiosperm portion of Clade-B can be divided into four subfamilies (Subfamilies B1, B2, B3 and B4).

Figure 6.

Phylogeny of the Clade-B AHL gene family in land plants using Bayesian analysis. Clade-B AHLs could be distinguished into 4 subfamilies (B1, B2, B3 and B4). Type-III AHLs that form sub-clades have been highlighted by gradient boxes (in Subfamilies B1 and B4) or pointed out by ③ if within Type-II AHL sub-clades. Type-II AHLs are pointed out by ② if within a Type-III AHL sub-clades (within Subfamily B4). Green boxes represent AHL genes from Poaceae, yellow boxes denote genes from Fabaceae, blue boxes denote genes from Rosaceae, orange boxes denote genes from Malpighiales, and red boxes denote genes from Brassicaceae. Numbers near branches indicate the Bayesian posterior probabilities for given clades. The red dots at internal nodes denote where gene duplication events have occurred.

Figure 7.

Phylogeny of the Clade-B AHL gene family in land plants using Bayesian analysis. Clade-B AHLs could be distinguished into 4 subfamilies (B1, B2, B3 and B4). Type-III AHLs that form sub-clades have been highlighted by gradient boxes (in Subfamilies B1 and B4) or pointed out by ③ if within Type-II AHL sub-clades. Type-II AHLs are pointed out by ② if within a Type-III AHL sub-clades (within Subfamily B4). Green boxes represent AHL genes from Poaceae, yellow boxes denote genes from Fabaceae, blue boxes denote genes from Rosaceae, orange boxes denote genes from Malpighiales, and red boxes denote genes from Brassicaceae. Numbers near branches indicate the Bayesian posterior probabilities for given clades. The red dots at internal nodes denote where gene duplication events have occurred.

In Subfamilies B1 and B4, members of the Type-III AHLs tend to group together and form Type-III AHL sub-clades (highlighted with gradient shaded box). Individual members of Type-II AHLs can be observed within the Subfamily B4 Type-III AHL sub-clades. This indicates possible regaining of the Type-I AT-hook motif within this subfamily, suggesting that not all Type-I AT-hooks are homologous. Individual Type-III AHLs also exist within the Type-II AHL sub-clades (such as Subfamilies B2, B3 and B4). This suggests an independent loss of the Type-I AT-hook motifs by AHL proteins within these subfamilies. Taken together, this indicates there are close evolutionary relationships between these two types of AHLs with, apparently, multiple transitions from Type-II to Type-III AHLs, and from Type-III to Type-II AHLs. The genomes of the moss Physcomitrella patens and lycophyte Selaginella moellendorffii do not contain Type-III AHLs, suggesting that the loss of the Type-I AT-hook motif in Clade-B occurred after lycophytes diverged from the rest of vascular plants (Figures 1a and 6).

Similar to their counterparts in Clade A, the Clade B AHLs also experienced multiple gene duplication and loss events during angiosperm diversification (Figures 6 and 7). Subfamily B1-B4 AHLs emerged from lineage divergence events and further expanded via multiple gene duplication/loss/divergence events (Table 1). In each extant plant species, Clade-B AHLs experienced similar numbers of gene duplication/loss events as their counterparts in Clade-A, suggesting shared evolutionary pressure between the two clades.

Members of each AHL monophyletic clade share similar expression patterns

To test the hypothesis that Clade-A and -B AHLs evolved independently, we examined the expression patterns of the AHLs in Arabidopsis thaliana using Genevestigator V3 [66]. Based on their expression patterns across various tissues at different developmental stages, the 29 Arabidopsis thaliana AHLs can be clearly distinguished into two groups (Additional file 10). A careful examination reveals that the Type-II and -III AtAHLs tend to share similar expression patterns. Type-II and -III AtAHLs, which constitute the Clade-B AHLs, are primarily expressed during seed and flower development. They are only moderately expressed in other tissues. On the other hand, Type-I AtAHLs, which constitute the Clade-A AHLs, are primarily expressed during vascular tissue and root development, which are distinctly different from the expression patterns observed for Type-II and -III AHLs. Such distinct expression patterns between the two clades of AHLs can also be observed in Zea mays (Additional file 11).

Discussion

The AHL gene family was first described about 10 years ago, as a group of plant-specific genes encoding proteins containing one or two copies of the AT-hook motif and a 120-amino-acid PPC domain [32]. In this study, AHL proteins have been identified in various plant species, including the early diverging mosses and lycophytes, as well as several angiosperm families [46]. We have further classified the AHL proteins into three types based on the number and composition of these two domains. Accordingly, both the AT-hook motifs and PPC domains of the AHL proteins can be classified into two types based on the phylogenetic analysis performed in this study.

From the prokaryotic PPC proteins to the AHL proteins in land plants

The PPC domain found in the AHL proteins exists by itself as a single protein in prokaryotes [32]. Individual strains of Bacteria and Archaea contain one gene encoding a PPC protein (Additional file 8). This observation suggests a role for the PPC domain in fundamental biological processes that has been conserved since prokaryotes throughout evolution. It is intriguing to note that even in the eukaryotic photosynthetic phytoplankton, such as Micromonas pusila [50] and Ostreococcus lucimarinus [51], the PPC protein still exists as a single gene. This observation indicates that the association with an AT-hook motif is not necessary for the functions of the PPC protein/domain in prokaryotes and early eukaryotes.

The appearance of the AHL proteins may have occurred between the emergence of the embryophytes and tracheophytes (pointed out by the red star in Figure 1a). The primitive AHL proteins emerged when the AT-hook motif fused with the PPC protein between the divergence of picoeukaryotes and the moss Physcomitrella patens. These primitive proteins later diversified and evolved into two monophyletic clades that comprise the three types of modern AHL proteins found in land plants. However, the evolutionary history of the expansion and later diversifications of these AHL genes are yet unexplored.

Ancient events on the AHL evolutionary timeline in land plants

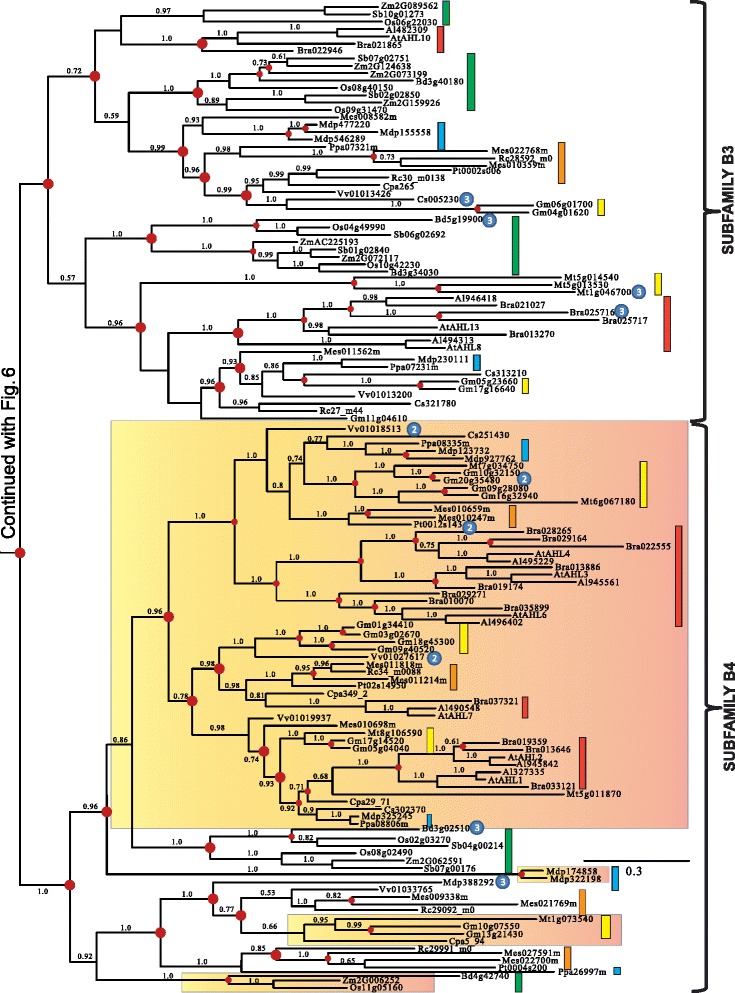

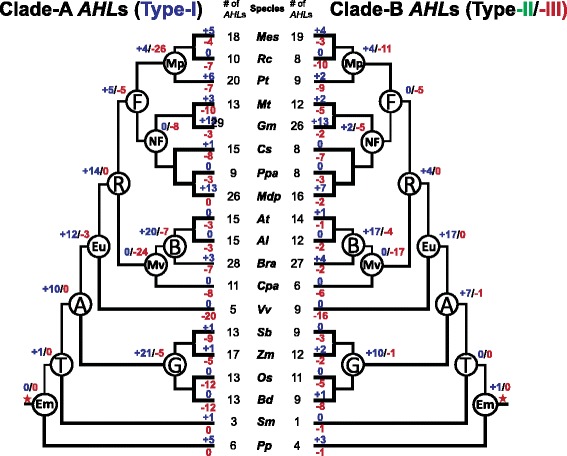

In order to better understand the expansion of the land-plant-specific AHL genes, we hypothesized the evolutionary events (duplications and deletions) that occurred at common ancestors across land plants (Figure 8). In the embryophytes and tracheophytes, there were few gene duplication/loss events occurring after the emergence of AHL genes in both AHL clades. However, both Clade-A and -B AHLs later experienced rapid expansion in angiosperms, which may be responsible for their large numbers in extant angiosperm species. During the emergence of the grass lineage, Clade-A AHLs exhibited more gene duplications than those in Clade-B. However, during the emergence of eudicots, Clade-B AHLs duplicated more rapidly. AHLs in Clade-B expanded in eudicots mainly through numerous gene duplication events; while those in Clade-A were also coupled with a few gene loss events. With the emergence of rosids, Clade-A AHLs duplicated more than their counterparts in Clade-B. Both clades later experienced dramatic gene losses during the emergence of Malvidae (Eurosids II).

Figure 8.

Evolutionary events of the AHL gene family in land plants. Numbers of gene duplication (shown in blue after “+”) and loss (shown in red after “-”) events were inferred for each internal node as well as for current extant species. The numbers of the AHL genes were also listed accordingly. The red star denotes when the AHL genes emerged. Al, Arabidopsis lyrata. At, Arabidopsis thaliana. Bd, Brachypodium distachyon. Bra, Brassica rapa. Cpa, Carica papaya. Cs, Cucumis sativus. Gm, Glycine max. Mdp, Malus domestica. Mes, Manihot esculenta. Mt, Medicago truncatula. Os, Oryza sativa. Pp, Physcomitrella patens. Ppa, Prunus persica. Pt, Populus trichocarpa. Rc, Ricinus communis. Sb, Sorghum bicolor. Sm, Selaginella moellendorffii. Vv, Vitis vinifera. Zm, Zea mays. A, Angiosperms. B, Brassicaceae. Em, Embryophyta. Eu, Eudicots. F, Fabidae (Eurosids I). G, Grasses. Mp, Malpighiales. Mv, Malvidae (Eurosids II). NF, Nitrogen fixing. T, Tracheophyta (vascular plants).

The most dramatic difference between Clade-A and -B AHLs appears within the emergence of Fabidae (Eurosids I). Clade-A AHLs showed rapid birth-and-death events; while the Clade-B copies experienced only gene loss events. This is in direct contrast to the AHL genes in the emergence of nitrogen fixing species. Clade-A AHLs endured rapid gene losses; while Clade-B copies experienced birth-and-death events. In Malpighiales and Brassicaceae, both clades also emerged through gene birth-and-death events.

A model for the evolutionary history of the AHL gene family in land plants

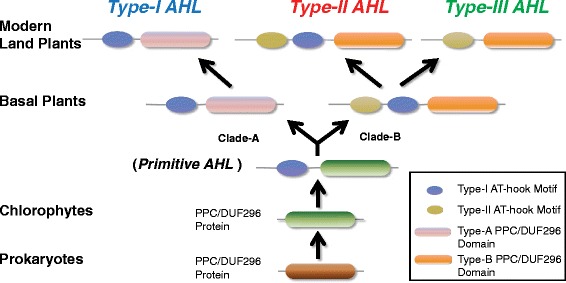

Based on the results in this study, we propose a model to describe the evolutionary history of the AHL gene family in land plants (Figure 9). In this model, the PPC gene existed by itself and encoded a PPC protein in prokaryotes as well as in early Viridiplantae. Prior to the divergence of extant embryophytes, the PPC domain became associated with a Type-I AT-hook motif to form a primitive intron-less AHL gene. Another Type-II AT-hook motif was further acquired by this type of primitive AHL before the divergence of mosses from the rest of land plants to form a second type of AHL gene. This new type of AHL further acquired introns in their genomic sequences. The emergence of both types of AHLs occurred somewhere between the divergence of picoeukaryotes and mosses. These two types of primitive AHLs duplicated, differentiated and further developed independently into members of Type-I and -II AHLs in early land plants, defining the two clades (Clade-A and -B). This model is supported by the observation that only these two types of AHLs could be found in mosses and lycophytes (Figure 1). Members of the intron-containing Type-II AHLs further diversified, some losing the Type-I AT-hook motif while retaining the type-II AT-hook motif, forming the intron-containing Type-III AHLs. While we have a general idea of when these events occurred, more detailed sampling among green algae, particularly the streptophyte algae, and more land plant lineages (liverworts, hornworts, ferns, gymnosperms, and monocots other than grasses) is needed to fully resolve the timing of gains and losses of the AT-hook motifs and duplication/deletion events.

Figure 9.

Evolution scenario of the AHL gene family in land plants. In prokaryotes and picoeukaryotes, the PPC domain exists by itself as a PPC protein. The AHL gene family emerged in Embryophytes by incorporating a Type-I AT-hook motif at the N-terminus of the PPC domain, forming primitive Type-I AHL protein(s). The AHL genes were further duplicated and gradually evolved into two clades (Clade-B with newly emerged Type-II AHLs by incorporating one Type-II AT-hook and Clade-A with Type-I AHLs). Along the evolutionary division into the two clades, the PPC domains in the AHL gene family were also evolved into two types. Through the evolution of modern land plants, members of the Type-II AHLs lost the Type-I AT-hook motif and gradually evolved into the Type-III AHLs.

AHL genes belong to the conserved “Gene Tool Kit” in plant evolution

Since they originated and diversified early in land plant evolution, the AHL genes also belong to the conserved “gene tool kit” of ancient plants. Throughout the evolution of land plants, the AHLs co-evolved with other “tool kit” members to regulate essential biological processes. The proposed co-evolution is supported by the observed genetic interactions with other ancient plant gene families, such as the NAC transcription factors and the MADS-box genes [33,67]. This hypothesis is also supported by the observed physical interactions of AHL proteins with histones (H2B, H3 and H4), TCPs (TCP4, TCP13, and TCP14), ATAF2 and DELLA proteins [33,68].

The observed physical interactions of the AHL proteins with other non-AHL transcription factors as well as with themselves led to a recently proposed “enhanceosome” molecular model [33]. In this model, it is proposed that the AHL proteins interact with each other to form homo-/hetero-trimer complexes via their PPC domains [33,69]. A conserved 6-amino-acid motif in the PPC domain from each monomer AHL protein acts together with those from the other two monomers to compose a quaternary domain. This domain in turn may mediate physical interactions with other transcription factors. In this study, over-expression of one Glycine max AHL PPC domain recapitulated the long-hypocotyl phenotype reminiscent of over-expressing its Arabidopsis thaliana counterpart (Figure 2). This indicates that the AHL PPC domains may serve evolutionarily conserved roles in regulating biological processes in multiple plant species. The AHL proteins share similar secondary and tertiary structures (Figure 2). In particular, the 6-amino-acid motif, Gly-Arg-Phe-Glu-Ile-Leu, is highly conserved in the PPC domains of AHLs from all land plants (Additional file 4). Therefore, it is possible that the functional conservation of the AHL proteins is achieved through the preservation of interacting partners among different plant species. In this study, we showed that Arabidopsis thaliana SOB3/AtAHL29 can physically interact with the Glycine max Gm06g01650.1 PPC domain (Figure 2d,e). This observation supports the hypothesis that the AHL proteins from different species can interact with each other via their PPC domains. It would be interesting to test if the preservation of physical interactions between AHL proteins is also conserved among those from more distantly related plant species, such as between AHLs from the moss Physcomitrella patens and angiosperms, or from monocot and dicot plants. In addition, we have predicted the orthologous and homologous AHL genes in the examined plant species (Additional files 12 and 13). It would be intriguing to examine if the orthologous/homologous AHLs share similar interactions, genetic and/or physical, with other non-AHL orthologous/homologous partners.

Biological functions of the AHL proteins at AT-rich chromosomal DNA

Besides the potential for shared physical interacting partners, the AHL proteins in the land plant species examined in this study also contain either one copy of Type-I or -II AT-hook motifs or both types. These two types of AT-hook motifs have also been found in the mammalian HMGA proteins [34]. Mammalian HMGA1 binds to AT-rich DNA and serves as an architectural protein which alters the local chromatin state and modulates gene expression through both protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions [70-73]. The similar possession of AT-hook motifs by both AHLs and HMGAs suggest that they may share binding affinities for AT-rich DNA.

This association of the AT-hook motif with the PPC domain is likely to physically direct these plant PPC domains to AT-rich chromosomal regions. This notion is supported by the observation that Arabidopsis thaliana AHL1 binds to the AT-rich scaffold/matrix attachment regions (S/MARs) and its AT-hook motif is indispensable for AHL1’s DNA binding capacity [32]. The S/MARs have been suggested to primarily localize near the transcription start sites [74,75] or correlate with the origins of DNA replication [76]. Several Arabidopsis thaliana AHL proteins bind to gene promoter regions and serve as transcriptional regulators [38,77]. Therefore, it is likely that the potential targeting of the PPC protein to the S/MARs is correlated with functions in gene transcriptional regulation. It would be interesting to examine and compare the biological functions of both PPC proteins in Bacteria and Archaea with the AHL proteins in land plants in order to shed light on the potential evolutionarily conserved functions of this domain.

In this study, we proposed an evolutionary hypothesis for the diversification of AHL genes, from a prokaryotic single-copy gene encoding the PPC protein lacking an AT-hook motif, to three types of land plant AHL proteins incorporating two types of PPC domains and two types of AT-hook motifs. However, the biological functions of these three types of AHL proteins still need to be determined. Further experiments need to be performed to reveal their binding sites along plant chromosomes and the corresponding biological regulatory roles. It should be noted that the inferred evolutionary events in this study are based on the retrieved full-length AHL sequences available from current releases of completely sequenced plant genomes. Further analysis should incorporate sequences from additional plant species (particularly ferns and gymnosperms) to improve our understanding of the diversification and functional evolution of the three types of AHL proteins.

Conclusion

In this study, over 500 full-length AHL genes have been identified from 19 fully sequenced plant genomes, ranging from the early diverging Physcomitrella patens and Selaginella to a variety of monocot and dicot flowering plants. Our analyses suggest that the AHLs can be classified into three types (Type-I/-II/-III) based on the number and composition of their functional domains, the AT-hook motif(s) and PPC domain. We further inferred their phylogenies in land plants via Bayesian inference analysis. The AHL genes emerged in embryophytes and have evolved into two distinct clades with Type-I AHLs diversifying in Clade-A and the other two types together diversifying into Clade-B. Our study indicates that Clade-A and -B AHLs diverged before the separation of moss Physcomitrella patens from the vascular plant lineage. In angiosperms, Clade-A AHLs expanded into 5 subfamilies; while, the ones in Clade-B expanded into 4 subfamilies.

Examination of their expression patterns suggests that the AHLs within each clade share similar patterns of expression with each other. While, the AHLs between the two clades exhibit distinct expression patterns from each other, suggesting potential conserved biological functions within each clade since their divergence along land plant evolution.

Manipulating the AHL genes has been suggested to have tremendous effects to positively affect agriculture through increasing seedling establishment, plant biomass and improving plant immunity [33,42,78,79]. Our analyses suggest that the AHL genes from different land plant species may share conserved functions in regulating plant growth and development. Over-expression of a Glycine max AHL PPC domain in Arabidopsis thaliana recapitulates the phenotype observed when over-expressing its Arabidopsis thaliana counterpart. Our study further suggest that such functional conservation may be due to conserved physical interactions among the PPC domains of AHL proteins. In the end, our analyses reveal a possible evolutionary scenario for the AHL gene family in land plants, which will facilitate the design of new studies probing their biological functions and subsequently lead to improvements in crop biomass production.

Methods

Data retrieval

The amino acid sequences as well as coding sequences for the members of the Arabidopsis thaliana AHL gene family were retrieved from the TAIR website [32,41,80] and were further used as queries for gene search using BLAST, TBLASTN, BLASTP and PSI_BLAST for AHL genes in the Phytozome database [46] within the related plant species with a cut-off E value set at 1e−2. The obtained results were further used as additional queries. Only intact gene sequences comprised of both AT-hook motif(s) and PPC domain were included and used as additional queries to perform in-depth gene searches in the Phytozome database. For further phylogenetic analysis, only protein sequences were used.

Cloning of AHL genes from Glycine max and Triticum aestivum

Genomic DNA as well as mRNA were prepared from Triticum aestivum seedlings using DNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen) and RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen). cDNA was further prepared using iScript Advanced cDNA Synthesis Kit for RT-PCR (Bio-RAD). Primer pairs (TaAHL1: 5′-ATG GGG AGC ATG GAC GGC CAC CC-3′ and 5′-CTA GAA TGA CGT CGG CGG AGG CCG C-3′; TaAHL3: 5′-ATG GCC ACC GGC AGC AGC AAG TGG TG-3′ and 5′-TCA GAT GCC GCC TCC CTG GTG GCC TC-3′) were used to clone TaAHL1 and TaAHL3 from both prepared genomic DNA and cDNA, correspondingly, and examined to be free-of-introns. Amino acid sequences of TaAHL1 and TaAHL3 proteins were predicted from their coding sequences and were used for further phylogenetic analysis. The nucleotide sequences of TaAHL1 and TaAHL3 have been deposited into NCBI GenBank (Accession numbers: TaAHL1/Taq1, KJ461850; TaAHL3/Taq3, KJ461851). Genomic DNA of Gm06g01650.1 was prepared from 6 day-old seedlings using ZR Plant DNA MiniPrep kit (Zymo Research). Coding sequence of its PPC domain was cloned using the primer pair (5′-TCC CCC CGG G A TGA AGC CAC CCG TCA TAG TCA CGC GCG AC-3′ and 5′-AAC TGC AGT CAA TCA TCA TCA TGC TGA TTC AAG G-3′). The amplicon and binary vector pCHF3 were digested by XmaI with PstI and ligated together. The resulted plasmid was subsequently transformed into agrobacterium GV3101 and further transformed into Arabidopsis thaliana Col-0 by the floral dipping method [81]. Surface-sterilized seeds were sown on 0.5× Linsmaier and Skoog modified basal medium (1.0% w/v phytogel and 1.5% w/v sucrose) and grown for 5 days at 25°C under 25 μmol∙s−1∙m−2 white light in a Percival E-30B growth chamber.

Yeast two-hybrid assay

A lexA-based Y2H system was used to test protein-protein interactions in yeast. The targeted yeast two-hybrid assay was performed as described in [33].

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analyses

The amino acid sequences of the Type-I AHL proteins were aligned using MUSCLE [82,83] and were further manually adjusted. Bayesian inference analysis was performed with the MrBayes 3.2.1 on XSEDE tool on CIPRES Science Gateway for 20 million generations with convergence at 0.022 [84]. The amino acid sequences of the Type-II and -III AHL proteins were aligned and manually adjusted. Bayesian inference analysis was performed with the MrBayes 3.2.1 for 10 million generations with convergence at 0.017. Generations were both sampled every 10,000 generations and the first 25% was set as burn-in.

Secondary and tertiary structure prediction

The amino acid sequences of the PPC domains were retrieved from the coding sequences of Gm06g01650.1, TaAHL1 (Taq1) and TaAHL3 (Taq3). The secondary and tertiary structures were predicted using the RaptorX Structure Prediction Server [85,86]. The tertiary structure figures were prepared using Pymol version 1.3 (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Schrodinger, LLC).

Inference of gene duplication and loss event

The plant species tree was adapted from the one in the Phytozome database [46]. The gene trees obtained from Bayesian inference analysis for each of the two AHL clades were reconciled with the plant species tree individually by Notung 2.6 [87] with default parameters. The orthologous and paralogous genes were further inferred by the Notung 2.6 program [87].

Availability of supporting data

The wheat AHL genes, TaAHL1 and TaAHL3 were deposited into NCBI GenBank (Accession numbers: TaAHL1/Taq1, KJ461850; TaAHL3/Taq3, KJ461851). All supporting data are included as additional files and have been uploaded to LabArchives, LLC. DOI: 10.6070/H4PC30B2.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative competitive grant # 2013-67013-21666 of the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (to M. M. N.), the O.A. Vogel Wheat Research Fund (to M.M.N.) and the Washington Grain Commission (to M. M. N.). This project was also supported by Global Plant Sciences Initiative Research Fellowship (Washington State University, to J. Z.), Pacific Seed Association Fellowship (to J. Z.), Maguire International Seed Technology Fellowship (to J. Z.), Lindahl Memorial Scholarship (to J. Z.) and Roscoe & Francis Cox Scholarship (to J. Z.). We are also grateful for support from the Brubbaken and Reinbold Monocot Breeding Fund (to M. M. N.).

Abbreviations

- AHL

AT-hook motif nuclear localized

- PPC/DUF296

Plant and prokaryote conserved/domain of unknown function #296

- SOB3

Suppressor of phytochrome B-4 #3

- ESC

ESCAROLA

- HRC

HERCULES

- Al

Arabidopsis lyrata

- At

Arabidopsis thaliana

- Bd

Brachypodium distachyon

- Bra

Brassica rapa

- Cpa

Carica papaya

- Cs

Cucumis sativus

- Gm

Glycine max

- Mdp

Malus domestica

- Mes

Manihot esculenta

- Mt

Medicago truncatula

- Os

Oryza sativa

- Pp

Physcomitrella patens

- Ppa

Prunus persica

- Pt

Populus trichocarpa

- Rc

Ricinus communis

- Sb

Sorghum bicolor

- Sm

Selaginella moellendorffii

- Vv

Vitis vinifera

- Zm

Zea mays

- A

Angiosperms

- B

Brassicaceae

- Em

Embryophyta

- Eu

Eudicots

- F

Fabidae (Eurosids I)

- G

Grasses

- Mp

Malpighiales

- Mv

Malvidae (Eurosids II)

- NF

Nitrogen fixing

- T

Tracheophyta (vascular plants)

Additional files

Chromosomal Locations of AHL Genes Identified in Arabidopsis thaliana . The AHL genes that are resulted from gene duplication were paired with red (adjacent pairs) and blue (distant pairs) lines.

Chromosomal Locations of AHL Genes Identified in Oryza sativa .

Amino acid sequences of the AHL proteins used in the analysis.

Sequence logo analysis of PPC domain of AHL proteins. Sequence logo analysis of the Type-A PPC domain (a) and Type-B PPC domain (b) in land-plant AHL proteins. The conserved six-amino-acid region was pointed out by the red boxes.

Amino acid sequences of wheat TaAHL1, TaAHL3 and soybean Gm06g01650.1. The AT-hook motif is underlined with green. The PPC domain is underlined with blue.

Alignment of two Arabidopsis thaliana AHLs, AtAHL27 and AtAHL29, with soybean Gm06g01650.1. The AT-hook motif is underlined with green. The PPC domain is underlined with blue.

Sequence logo analysis of the AT-hook motifs. Sequence logo analysis of the Type-I AT-hook motif from (a) the land-plant AHLs that only contain Type-I, not Type-II AT-hook, and from (b) the AHLs that also contain Type-II AT-hook. Sequence logo analysis of the Type-II AT-hook motif in (c) the AHLs that only contain Type-II, not Type-I AT-hook, and (d) the AHLs that also contain Type-I AT-hook. The star symbol represents the core sequence of the AT-hook motif. The conserved sequence downstream of the core sequences in Type-I and Type-II AT-hook motifs were pointed out by the triangle and diamond symbols accordingly.

PPC/DUF296 Genes Identified in Selected Picoeukaryotes and Prokaryotes.

Intron-mediated transcriptional enhancement of AHL genes in Arabidopsis thaliana . (a) Topology of the exon and intron arrangement of Arabidopsis thaliana AHL genes. (b) The intron-mediated enhancement scores of the first/second/third/fourth intron were shown. The grey line represents a score of 10, which indicates moderate capability of transcriptional enhancement. (c) The intron-mediated enhancement scores of each intron in AtAHLs were listed. The abilities of transcriptional enhancement were categorized with strong (orange color), relatively strong (light orange), moderate (light blue) and weak (no color).

Expression analysis of the AHL genes in Arabidopsis thaliana using Genevestigator V3.0. Similarities between expression profiles of AHL genes were calculated using Manhattan Distance method (www.genevestigator.com) [67]. Type-I AHLs were labeled in blue color. Type-II AHLs were labeled in green color. Type-III AHLs were labeled in red color.

Expression Analysis of the AHL Genes in Zea mays Using Genevestigator V3.0. Similarities between expression profiles of AHL genes were calculated using Pearson Correlation method (www.genevestigator.com) [67]. Type-I AHLs were labeled in blue color. Type-II AHLs were labeled in green color. Type-III AHLs were labeled in red color.

Inferred orthologs and paralogs of the Clade-A AHL genes in land plant species.

Inferred orthologs and paralogs of the Clade-B AHL genes in land plant species.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JZ conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, collected the sequences, performed bioinformatics analysis, cloned Gm06g01650.1-PPC sequence, performed its related transgenic study and wrote the manuscript. DSF performed the yeast two-hybrid analysis and participated in writing the manuscript. JQ cloned TaAHL1/Taq1 and TaAHL3/Taq3 from wheat. EHR participated in the design of the study, participated in performing the bioinformatics analysis and writing the manuscript. MMN participated in the design and coordination of the study and writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jianfei Zhao, jianfei.zhao@email.wsu.edu.

David S Favero, david.favero100@email.wsu.edu.

Jiwen Qiu, Email: jiwenqiu@wsu.edu.

Eric H Roalson, Email: eric_roalson@wsu.edu.

Michael M Neff, Email: mmneff@wsu.edu.

References

- 1.Floyd S, Bowman JL. The ancestral developmental tool kit of land plants. Int J Plant Sci. 2007;168(1):1–35. doi: 10.1086/509079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang H, Bowers JE, Wang X, Ming R, Alam M, Paterson AH. Synteny and collinearity in plant genomes. Science. 2008;320(5875):486–488. doi: 10.1126/science.1153917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ligrone R, Duckett JG, Renzaglia KS. Major transitions in the evolution of early land plants: a bryological perspective. Ann Bot. 2012;109(5):851–871. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pires ND, Dolan L. Morphological evolution in land plants: new designs with old genes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367(1588):508–518. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lynch M, Conery JS. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science. 2000;290(5494):1151–1155. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sterck L, Rombauts S, Vandepoele K, Rouze P, Van de Peer Y. How many genes are there in plants (… and why are they there)? Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10(2):199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson D, Werck-Reichhart D. A P450-centric view of plant evolution. Plant J. 2011;66(1):194–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nam J, Kim J, Lee S, An GH, Ma H, Nei MS. Type I MADS-box genes have experienced faster birth-and-death evolution than type II MADS-box genes in angiosperms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(7):1910–1915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308430100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mondragon-Palomino M, Theissen G. MADS about the evolution of orchid flowers. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13(2):51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shan H, Zahn L, Guindon S, Wall PK, Kong H, Ma H, DePamphilis CW, Leebens-Mack J. Evolution of plant MADS box transcription factors: evidence for shifts in selection associated with early angiosperm diversification and concerted gene duplications. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26(10):2229–2244. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smaczniak C, Immink RG, Angenent GC, Kaufmann K. Developmental and evolutionary diversity of plant MADS-domain factors: insights from recent studies. Development. 2012;139(17):3081–3098. doi: 10.1242/dev.074674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jimenez S, Lawton-Rauh AL, Reighard GL, Abbott AG, Bielenberg DG. Phylogenetic analysis and molecular evolution of the dormancy associated MADS-box genes from peach. BMC Plant Biol. 2009;9:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnani E, Sjolander K, Hake S. From endonucleases to transcription factors: evolution of the AP2 DNA binding domain in plants. Plant Cell. 2004;16(9):2265–2277. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.023135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S, Soltis PS, Wall K, Soltis DE. Phylogeny and domain evolution in the APETALA2-like gene family. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23(1):107–120. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shigyo M, Hasebe M, Ito M. Molecular evolution of the AP2 subfamily. Gene. 2006;366(2):256–265. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rashid M, Guangyuan H, Guangxiao Y, Hussain J, Xu Y. AP2/ERF transcription factor in rice: genome-wide canvas and syntenic relationships between monocots and eudicots. Evol Bioinform Online. 2012;8:321–355. doi: 10.4137/EBO.S9369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dolan L. Plant evolution: TALES of development. Cell. 2008;133(5):771–773. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JH, Lin H, Joo S, Goodenough U. Early sexual origins of homeoprotein heterodimerization and evolution of the plant KNOX/BELL family. Cell. 2008;133(5):829–840. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hay A, Tsiantis M. KNOX genes: versatile regulators of plant development and diversity. Development. 2010;137(19):3153–3165. doi: 10.1242/dev.030049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ooka H, Satoh K, Doi K, Nagata T, Otomo Y, Murakami K, Matsubara K, Osato N, Kawai J, Carninci P, Hayashizaki Y, Suzuki K, Kojima K, Takahara Y, Yamanoto K, Kikuchi S. Comprehensive analysis of NAC family genes in Oryza sativa and Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Res. 2003;10(6):239–247. doi: 10.1093/dnares/10.6.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu T, Nevo E, Sun D, Peng J. Phylogenetic analyses unravel the evolutionary history of NAC proteins in plants. Evolution. 2012;66(6):1833–1848. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu R, Qi G, Kong Y, Kong D, Gao Q, Zhou G. Comprehensive analysis of NAC domain transcription factor gene family in Populus trichocarpa. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:145. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Floyd SK, Zalewski CS, Bowman JL. Evolution of class III homeodomain-leucine zipper genes in streptophytes. Genetics. 2006;173(1):373–388. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.054239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prigge MJ, Clark SE. Evolution of the class III HD-Zip gene family in land plants. Evol Dev. 2006;8(4):350–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2006.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cote CL, Boileau F, Roy V, Ouellet M, Levasseur C, Morency MJ, Cooke JE, Seguin A, MacKay JJ. Gene family structure, expression and functional analysis of HD-Zip III genes in angiosperm and gymnosperm forest trees. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:273. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toledo-Ortiz G, Huq E, Quail PH. The Arabidopsis basic/helix-loop-helix transcription factor family. Plant Cell. 2003;15(8):1749–1770. doi: 10.1105/tpc.013839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li X, Duan X, Jiang H, Sun Y, Tang Y, Yuan Z, Guo J, Liang W, Chen L, Yin J, Ma H, Wang J, Zhang D. Genome-wide analysis of basic/helix-loop-helix transcription factor family in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006;141(4):1167–1184. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.080580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pires N, Dolan L. Origin and diversification of basic-helix-loop-helix proteins in plants. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27(4):862–874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin-Trillo M, Cubas P. TCP genes: a family snapshot ten years later. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15(1):31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mondragon-Palomino M, Trontin C. High time for a roll call: gene duplication and phylogenetic relationships of TCP-like genes in monocots. Ann Bot. 2011;107(9):1533–1544. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcr059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preston JC, Hileman LC. Parallel evolution of TCP and B-class genes in Commelinaceae flower bilateral symmetry. Evodevo. 2012;3:6. doi: 10.1186/2041-9139-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujimoto S, Matsunaga S, Yonemura M, Uchiyama S, Azuma T, Fukui K. Identification of a novel plant MAR DNA binding protein localized on chromosomal surfaces. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;56(2):225–239. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-3249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao J, Favero DS, Peng H, Neff MM. Arabidopsis thaliana AHL family modulates hypocotyl growth redundantly by interacting with each other via the PPC/DUF296 domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(48):E4688–E4697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219277110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aravind L, Landsman D. AT-hook motifs identified in a wide variety of DNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(19):4413–4421. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.19.4413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huth JR, Bewley CA, Nissen MS, Evans JN, Reeves R, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. The solution structure of an HMG-I(Y)-DNA complex defines a new architectural minor groove binding motif. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4(8):657–665. doi: 10.1038/nsb0897-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin LY, Nakano H, Nakamura S, Uchiyama S, Fujimoto S, Matsunaga S, Kobayashi Y, Ohkubo T, Fukui K. Crystal structure of Pyrococcus horikoshii PPC protein at 1.60 A resolution. Proteins-Struct Func Bioinf. 2007;67(2):505–507. doi: 10.1002/prot.21270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin LY, Nakano H, Uchiyama S, Fujimoto S, Matsunaga S, Nakamura S, Kobayashi Y, Ohkubo T, Fukui K. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of a conserved domain in plants and prokaryotes from Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3. Acta Crystallograph Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2005;61:414–416. doi: 10.1107/S1744309105007815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsushita A, Furumoto T, Ishida S, Takahashi Y. AGF1, an AT-hook protein, is necessary for the negative feedback of AtGA3ox1 encoding GA 3-oxidase. Plant Physiol. 2007;143(3):1152–1162. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.093542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Endt DV, Silva MSE, Kijne JW, Pasquali G, Memelink J. Identification of a bipartite jasmonate-responsive promoter element in the Catharanthus roseus ORCA3 transcription factor gene that interacts specifically with AT-hook DNA-binding proteins. Plant Physiol. 2007;144(3):1680–1689. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.096115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rashotte AM, Carson SD, To JP, Kieber JJ. Expression profiling of cytokinin action in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;132(4):1998–2011. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Street IH, Shah PK, Smith AM, Avery N, Neff MM. The AT-hook-containing proteins SOB3/AHL29 and ESC/AHL27 are negative modulators of hypocotyl growth in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2008;54(1):1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang C. United States Patent (US6,717,034 B2) 2004. Method for Modifying Plant Biomass. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yun J, Kim YS, Jung JH, Seo PJ, Park CM. The AT-hook motif-containing protein AHL22 regulates flowering initiation by modifying FLOWERING LOCUS T chromatin in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(19):15307–15316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.318477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lim PO, Kim Y, Breeze E, Koo JC, Woo HR, Ryu JS, Park DH, Beynon J, Tabrett A, Buchanan-Wollaston V, Nam HG. Overexpression of a chromatin architecture-controlling AT-hook protein extends leaf longevity and increases the post-harvest storage life of plants. Plant J. 2007;52(6):1140–1153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu H, Zou Y, Feng N. Overexpression of AHL20 negatively regulates defenses in Arabidopsis. J Int Plant Biol. 2010;52(9):801–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goodstein DM, Shu S, Howson R, Neupane R, Hayes RD, Fazo J, Mitros T, Dirks W, Hellsten U, Putnam N, Rokhsar DS. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D1178–D1186. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim HB, Oh CJ, Park YC, Lee Y, Choe S, An CS, Choi SB. Comprehensive analysis of AHL homologous genes encoding AT-hook motif nuclear localized protein in rice. BMB Rep. 2011;44(10):680–685. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2011.44.10.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Merchant SS, Prochnik SE, Vallon O, Harris EH, Karpowicz SJ, Witman GB, Terry A, Salamov A, Fritz-Laylin LK, Marechal-Drouard L, Marshall WF, Qu LH, Nelson DR, Sanderfoot AA, Spalding MH, Kapitonov VV, Ren Q, Ferris P, Lindquist E, Shapiro H, Lucas SM, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Cardol P, Cerutti H, Chanfreau G, Chen CL, Cognat V, Croft MT, Dent R, et al. The Chlamydomonas genome reveals the evolution of key animal and plant functions. Science. 2007;318(5848):245–250. doi: 10.1126/science.1143609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prochnik SE, Umen J, Nedelcu AM, Hallmann A, Miller SM, Nishii I, Ferris P, Kuo A, Mitros T, Fritz-Laylin LK, Hellsten U, Chapman J, Simakov O, Rensing SA, Terry A, Pangilinan J, Kapitonov V, Jurka J, Salamov A, Shapiro H, Schmutz J, Grimwood J, Lindquist E, Lucas S, Grigoriev IV, Schimitt R, Kirk D, Rokhsar DS. Genomic analysis of organismal complexity in the multicellular green alga Volvox carteri. Science. 2010;329(5988):223–226. doi: 10.1126/science.1188800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Worden AZ, Lee JH, Mock T, Rouze P, Simmons MP, Aerts AL, Allen AE, Cuvelier ML, Derelle E, Everett MV, Foulon E, Grimwood J, Gundlach H, Henrissat B, Napoli C, McDonald SM, Parker MS, Rombauts S, Salamov A, Von Dassow P, Badger JH, Coutinho PM, Demir E, Dubchak I, Gentemann C, Eikrem W, Gready JE, John U, Lanier W, Lindquist EA, et al. Green evolution and dynamic adaptations revealed by genomes of the marine picoeukaryotes Micromonas. Science. 2009;324(5924):268–272. doi: 10.1126/science.1167222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palenik B, Grimwood J, Aerts A, Rouze P, Salamov A, Putnam N, Dupont C, Jorgensen R, Derelle E, Rombauts S, Zhou K, Otillar R, Merchant SS, Podell S, Gaasterland T, Napoli C, Gendler K, Manuell A, Tai V, Vallon O, Piganeau G, Jancek S, Heijde M, Jabbari K, Bowler C, Lohr M, Robbens S, Werner G, Dubchak I, Pazour GJ, et al. The tiny eukaryote Ostreococcus provides genomic insights into the paradox of plankton speciation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(18):7705–7710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611046104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Derelle E, Ferraz C, Rombauts S, Rouze P, Worden AZ, Robbens S, Partensky F, Degroeve S, Echeynie S, Cooke R, Saeys Y, Wuyts J, Jabbari K, Bowler C, Panaud O, Piegu B, Ball SG, Ral JP, Bouget FY, Piganeau G, De Baets B, Picard A, Delseny M, Demaille J, Van de Peer Y, Moreau H. Genome analysis of the smallest free-living eukaryote Ostreococcus tauri unveils many unique features. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(31):11647–11652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604795103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schnable PS, Ware D, Fulton RS, Stein JC, Wei F, Pasternak S, Liang C, Zhang J, Fulton L, Graves TA, Minx P, Reily AD, Courtney L, Kruchowski SS, Tomlinson C, Strong C, Delehaunty K, Fronick C, Courtney B, Rock SM, Belter E, Du F, Kim K, Abbott RM, Cotton M, Levy A, Marchetto P, Ochoa K, Jackson SM, Gillam B, et al. The B73 maize genome: complexity, diversity, and dynamics. Science. 2009;326(5956):1112–1115. doi: 10.1126/science.1178534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goff SA, Ricke D, Lan TH, Presting G, Wang R, Dunn M, Glazebrook J, Sessions A, Oeller P, Varma H, Hadley D, Hutchison D, Martin C, Katagiri F, Lange BM, Moughamer T, Xia Y, Budworth P, Zhong J, Miguel T, Paszkowski U, Zhang S, Colbert M, Sun WL, Chen L, Cooper B, Park S, Wood TC, Mao L, Quail P, et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica) Science. 2002;296(5565):92–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu J, Hu S, Wang J, Wong GK, Li S, Liu B, Deng Y, Dai L, Zhou Y, Zhang X, Cao M, Liu J, Sun J, Tang J, Chen Y, Huang X, Lin W, Ye C, Tong W, Cong L, Geng J, Han Y, Li L, Li W, Hu G, Li J, Liu Z, Qiu Q, Li T, Wang X, et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica) Science. 2002;296(5565):79–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1068037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.International Brachypodium Initiative Genome sequencing and analysis of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Nature. 2010;463(7282):763–768. doi: 10.1038/nature08747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paterson AH, Bowers JE, Bruggmann R, Dubchak I, Grimwood J, Gundlach H, Haberer G, Hellsten U, Mitros T, Poliakov A, Schmutz J, Spannagl M, Tang H, Wang X, Wicker T, Bharti AK, Chapman J, Feltus FA, Gowik U, Grigoriev IV, Lyons E, Maher CA, Martis M, Narechania A, Otillar RP, Penning BW, Salamov AA, Wang Y, Zhang L, Carpita NC, et al. The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature. 2009;457(7229):551–556. doi: 10.1038/nature07723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reddy AS, Marquez Y, Kalyna M, Barta A. Complexity of the alternative splicing landscape in plants. Plant Cell. 2013;25(10):3657–3683. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.117523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Staiger D, Brown JW. Alternative splicing at the intersection of biological timing, development, and stress responses. Plant Cell. 2013;25(10):3640–3656. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.113803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vitulo N, Forcato C, Carpinelli EC, Telatin A, Campagna D, D’Angelo M, Zimbello R, Corso M, Vannozzi A, Bonghi C, Lucchin M, Valle G. A deep survey of alternative splicing in grape reveals changes in the splicing machinery related to tissue, stress condition and genotype. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14(1):99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nyiko T, Kerenyi F, Szabadkai L, Benkovics AH, Major P, Sonkoly B, Merai Z, Barta E, Niemiec E, Kufel J, Silhavy D. Plant nonsense-mediated mRNA decay is controlled by different autoregulatory circuits and can be induced by an EJC-like complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(13):6715–6728. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morello L, Breviario D. Plant spliceosomal introns: not only cut and paste. Curr Genomics. 2008;9(4):227–238. doi: 10.2174/138920208784533629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parra G, Bradnam K, Rose AB, Korf I. Comparative and functional analysis of intron-mediated enhancement signals reveals conserved features among plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(13):5328–5337. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmutz J, Cannon SB, Schlueter J, Ma J, Mitros T, Nelson W, Hyten DL, Song Q, Thelen JJ, Cheng J, Xu D, Hellsten U, May GD, Yu Y, Sakurai T, Umezawa T, Bhattacharyya MK, Sandhu D, Valliyodan B, Lindquist E, Peto M, Grant D, Shu S, Goodstein D, Barry K, Futrell-Griggs M, Abernathy B, Du J, Tian Z, Zhu L, et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature. 2010;463(7278):178–183. doi: 10.1038/nature08670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Velasco R, Zharkikh A, Affourtit J, Dhingra A, Cestaro A, Kalyanaraman A, Fontana P, Bhatnagar SK, Troggio M, Pruss D, Salvia S, Pindo M, Baldi P, Castelletti S, Cavaiuolo M, Coppola G, Costa F, Cova V, Dal Ri A, Goremykin V, Komjanc M, Longhi S, Magnago P, Malacarne G, Malnoy M, Micheletti D, Moretto M, Perazzolli M, Si-Ammour A, Vezzulli S. The genome of the domesticated apple (Malus x domestica Borkh.) Nat Genet. 2010;42(10):833–839. doi: 10.1038/ng.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hruz T, Laule O, Szabo G, Wessendorp F, Bleuler S, Oertle L, Widmayer P, Gruissem W, Zimmermann P. Genevestigator v3: a reference expression database for the meta-analysis of transcriptomes. Adv Bioinformatics. 2008;2008:420747. doi: 10.1155/2008/420747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jin Y, Luo Q, Tong H, Wang A, Cheng Z, Tang J, Li D, Zhao X, Li X, Wan J, Jiao Y, Chu C, Zhu L. An AT-hook gene is required for palea formation and floral organ number control in rice. Dev Biol. 2011;359(2):277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arabidopsis Interactome Mapping Consortium Evidence for network evolution in an Arabidopsis interactome map. Science. 2011;333(6042):601–607. doi: 10.1126/science.1203877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gallavotti A, Malcomber S, Gaines C, Stanfield S, Whipple C, Kellogg E, Schmidt RJ. BARREN STALK FASTIGIATE1 is an AT-hook protein required for the formation of maize ears. Plant Cell. 2011;23(5):1756–1771. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.084590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reeves R. Molecular biology of HMGA proteins: hubs of nuclear function. Gene. 2001;277(1–2):63–81. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00689-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lomvardas S, Thanos D. Modifying gene expression programs by altering core promoter chromatin architecture. Cell. 2002;110(2):261–271. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00822-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fusco A, Fedele M. Roles of HMGA proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(12):899–910. doi: 10.1038/nrc2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kishi Y, Fujii Y, Hirabayashi Y, Gotoh Y. HMGA regulates the global chromatin state and neurogenic potential in neocortical precursor cells. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(8):1127–1133. doi: 10.1038/nn.3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Allen GC, Spiker S, Thompson WF. Use of matrix attachment regions (MARs) to minimize transgene silencing. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;43(2–3):361–376. doi: 10.1023/A:1006424621037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pascuzzi PE, Flores-Vergara MA, Lee TJ, Sosinski B, Vaughn MW, Hanley-Bowdoin L, Thompson WF, Allen GC. In vivo mapping of arabidopsis scaffold/matrix attachment regions reveals link to nucleosome-disfavoring poly(dA:dT) tracts. Plant Cell. 2014;26(1):102–120. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.121194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vaughn JP, Dijkwel PA, Mullenders LH, Hamlin JL. Replication forks are associated with the nuclear matrix. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18(8):1965–1969. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.8.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Franco-Zorrilla JM, Lopez-Vidriero I, Carrasco JL, Godoy M, Vera P, Solano R. DNA-binding specificities of plant transcription factors and their potential to define target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(6):2367–2372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316278111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Century K, Reuber TL, Ratcliffe OJ. Regulating the regulators: the future prospects for transcription-factor-based agricultural biotechnology products. Plant Physiol. 2008;147(1):20–29. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.117887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gonzalez N, Beemster GT, Inze D. David and Goliath: what can the tiny weed Arabidopsis teach us to improve biomass production in crops? Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12(2):157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Huala E, Dickerman AW, Garcia-Hernandez M, Weems D, Reiser L, LaFond F, Hanley D, Kiphart D, Zhuang M, Huang W, Mueller LA, Bhattacharyya D, Bhaya D, Sobral BW, Beavis W, Meinke DW, Town CD, Somerville C, Rhee SY. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): a comprehensive database and web-based information retrieval, analysis, and visualization system for a model plant. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(1):102–105. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16(6):735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Miller MA, Pferffer W, Schwartz T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. Proceedings of the Gateway Computing Environments Workshop. 2010;14:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kallberg M, Margaryan G, Wang S, Ma J, Xu J. RaptorX server: a resource for template-based protein structure modeling. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1137:17–27. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0366-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kallberg M, Wang H, Wang S, Peng J, Wang Z, Lu H, Xu J. Template-based protein structure modeling using the RaptorX web server. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(8):1511–1522. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]