Abstract

Although family caregivers of patients with lung and other cancers show high rates of psychological distress, they underuse mental health services. This qualitative study aimed to identify barriers to mental health service use among 21 distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients. Caregivers had not received mental health services during the patient’s initial months of care at a comprehensive cancer centre in New York City. Thematic analysis of interview data was framed by Andersen’s model of health service use and Corrigan’s stigma theory. Results of our analysis expand Andersen’s model by providing a description of need variables (e.g., psychiatric symptoms), enabling factors (e.g., finances), and psychosocial factors associated with caregivers’ nonuse of mental health services. Regarding psychosocial factors, caregivers expressed negative perceptions of mental health professionals and a desire for independent management of emotional concerns. Additionally, caregivers perceived a conflict between mental health service use and the caregiving role (e.g., prioritizing the patient’s needs). Although caregivers denied stigma associated with service use, their anticipated negative self-perceptions if they were to use services suggest that stigma may have influenced their decision to not seek services. Findings suggest that interventions to improve caregivers’ uptake of mental health services should address perceived barriers.

Keywords: stigma, psychological distress, barriers, mental health service use, family caregivers, lung cancer

Introduction

In the United States, an estimated 4.6 million people care for a family member with cancer at home (National Alliance for Caregiving, 2009). Family caregivers provide more than half of the care needed by cancer patients (Blum & Sherman, 2010), and caregiving demands may adversely affect caregivers’ mental health (Kim & Given, 2008; Northouse et al., 2012). Research suggests that as many as 50% of cancer patients’ family caregivers experience significant anxiety or depressive symptoms (M. Braun et al., 2007; Fridriksdóttir et al., 2011; Lambert et al., 2013; Mosher et al., 2013a). Moreover, caregivers’ anxiety and depressive symptoms often persist during the initial months following the patient’s cancer diagnosis (Choi et al., 2012; Lambert et al., 2012). Elevated anxiety and depressive symptoms among cancer patients’ caregivers have been associated with health risk behaviours such as sleep disturbances (Gibbins et al., 2009) and smoking (Weaver et al., 2011).

Despite their high rates of psychological distress (M. Braun et al., 2007; Fridriksdóttir et al., 2011), family caregivers of cancer patients typically underuse mental health services in the U.S. (Mosher et al., 2013a; Vanderwerker et al., 2005; Wolff et al., 2007). For example, fewer than half (46%) of advanced cancer patients’ caregivers with a psychiatric disorder sought mental health care (Vanderwerker et al., 2005). In a nationally representative survey of family caregivers of chronically disabled community-dwelling older adults, including those with cancer, less than 5% of caregivers reported participating in a caregiver support group or using respite services (Wolff et al., 2007).

Caregiver-reported barriers to mental health service use have rarely been examined (Vanderwerker et al., 2005). Understanding caregivers’ reasons for not accessing mental health services is necessary for guiding the development of programs to promote appropriate service use. Thus, this study provides an in-depth exploration of factors contributing to nonuse of mental health services among distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients. We chose to focus on caregivers of lung cancer patients, as this disease may be especially distressing for caregivers due to its typically poor prognosis, high physical symptom burden (Spiro et al., 2008), and attributions of blame or stigma related to tobacco use (Lobchuk et al., 2008; Milbury et al., 2012).

Mental Health Service Use Theory

Andersen’s (1995) Behavioural Model of Health Service Use was the organizing framework for the current research. This widely acknowledged model has been applied to the study of mental health service use (Dhingra et al., 2010; Elhai & Ford, 2007). The model proposes the following individual and contextual determinants of healthcare use: (1) need for services as indicated by psychiatric symptoms and perceptions of functional capacity or coping abilities; (2) enabling factors, including family and community resources and their accessibility; and (3) predisposing factors such as demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age, race, education) and beliefs (e.g., attitudes towards health services, knowledge of services, values); (Andersen, 1995). Population-based studies of mental health service use in the U.S. have partially supported the Andersen model, suggesting that evaluated need for services (i.e., patient-reported psychiatric symptoms) and certain predisposing factors (e.g., age, gender) and enabling factors (e.g., health insurance, income) predict service use (Dhingra et al., 2010; Elhai & Ford, 2007). However, little attention has been paid to psychosocial predisposing factors in population-based surveys, including attitudes, knowledge, and values that may influence service use (Mojtabai et al., 2011; Sareen et al., 2007).

One psychosocial factor linked to nonuse of mental health services is internalized stigma (Livingston & Boyd, 2010; Vogel et al., 2006). This form of stigma occurs when affected individuals accept stereotypes about mental illness, expect social rejection, and believe that they are less valued because of their psychiatric symptoms (Corrigan et al., 2005; Corrigan et al., 2006; Livingston & Boyd, 2010). Thus, according to stigma theory (Corrigan, 2004; Corrigan et al., 2005), people may refrain from seeking mental health services in order to avoid the harmful consequences of psychiatric labels, such as feelings of inferiority or inadequacy. Results of a meta-analysis suggested that internalized stigma is negatively associated with treatment adherence among people with mental illness (Livingston & Boyd, 2010); however, findings regarding the impact of stigma on mental health service use have varied across definitions of stigma and sample characteristics (e.g., clinical versus non-clinical samples) (e.g., Cooper et al., 2003; Eisenberg et al., 2009; Golberstein et al., 2009; Rüsch et al., 2009; Vogel et al., 2006).

Internalized stigma may be especially relevant to understanding nonuse of mental health services among distressed family caregivers of medically ill patients, as the caregiving role involves societal expectations of emotional strength and prioritization of the patient’s needs above one’s own needs (Thomas et al., 2002). Thus, family caregivers may consider professional support seeking to be a sign of weakness or an acknowledgement of failure as a support provider. However, this hypothesis has yet to be examined in qualitative or quantitative research with family caregivers.

The Present Study

The goal of this qualitative study was to identify barriers to mental health service use among distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients. To achieve this goal, we conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with distressed caregivers who had not accessed mental health services during the initial months of the patient’s care at a cancer centre in the U.S. The ready availability of comprehensive mental health services at the cancer centre allowed us to examine individual barriers to service use. We aimed to extend Andersen’s (1995) model of health service use and stigma theory (Corrigan, 2004; Corrigan et al., 2005) by clarifying the need, enabling, and psychosocial predisposing factors involved in distressed family caregivers’ decision to not seek mental health services.

Methods

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from a comprehensive cancer centre in New York City between September 2009 and June 2010. The cancer centre’s institutional review board approved all study procedures. Purposive sampling was used to ensure diversity with regard to patient gender, age, racial or ethnic background, and disease stage. Patient eligibility was confirmed via medical record review and consultation with oncologists. During an oncology clinic visit, lung cancer patients identified and provided permission to contact their primary family caregiver (i.e., the person responsible for the majority of their unpaid, informal care) and collect cancer-related information from their medical record. All caregivers were enrolled within 12 weeks of the patient’s new visit to the cancer centre’s thoracic oncology clinic. Trained research assistants screened caregivers for eligibility and completed the informed consent process in clinic or via telephone. Eligible caregivers were fluent in English, at least 18 years of age, and reported anxiety or depressive symptoms exceeding the clinical cutoff (≥8) on the Anxiety or Depression subscales of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Bjelland et al., 2002; Zigmond & Snaith, 1983) at the time of recruitment. This measure has shown adequate reliability and validity (Bjelland et al., 2002). Coefficient alphas for Anxiety and Depression subscales in the current study were .69 and .76, respectively. Following study enrolment, all participants received brochures outlining comprehensive mental health services (i.e., psychiatric, psychological, and social work services) at the cancer centre. The types of available services and their contact information were discussed with each participant.

Data Collection

Caregivers completed standardized telephone assessments of their health, well-being, and mental health service utilization at baseline and three months later. Caregivers who had not received mental health services (i.e., individual or group psychotherapy or psychiatric medication) during the 3-month study period were invited to participate in an in-depth, semi-structured telephone interview so as to examine barriers to mental health service use.

Interviews were conducted within three weeks of the follow-up assessment by an experienced master’s level qualitative methodologist. The interview protocol included questions about caregivers’ greatest challenges in caring for the patient, their attitudes towards mental health services, and their service preferences. Interviews ranged from 35 to 50 minutes and were digitally recorded. Qualitative findings regarding challenges in caring for the patient have been published (Mosher et al., 2013b). The present analysis focused on caregivers’ responses to questions regarding their attitudes toward mental health services. During the interview, caregivers were first asked to select one of three statements that best described their current situation with regard to seeking mental health services: (1) “You have tried to get help, but are still waiting”; (2) “You have not yet tried but may do so in the future”; or (3) “You would not consider seeking professional help for emotional concerns.” Subsequent questions assessed their perceptions of mental health services: “When you think about getting professional help such as counselling for emotional concerns, what thoughts come to mind?” and “How do you think you would feel if you spoke with a counsellor about your concerns?” Further questions were tailored to the caregiver’s situation with regard to mental health service seeking. Specifically, caregivers who had tried to obtain mental health services were asked to describe the steps that they had taken to access services and reasons for nonuse of services despite their efforts to obtain them. Caregivers who indicated that they had not yet tried counselling but may do so in the future were asked to describe anything that might make them reluctant to try counselling. Finally, caregivers who indicated that they would not consider seeking professional help for emotional concerns were asked to elaborate (i.e., “Could you tell me more about this?”). The interviewer asked follow-up questions to obtain a detailed narrative and to explore whether caregivers perceived stigma associated with seeing a counsellor. Caregivers received $25 for participating in this interview.

Caregivers reported their demographic information at baseline. Patients’ medical information (i.e., lung cancer type and stage, date of diagnosis, and treatments received) were collected from medical records.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and imported into Atlas.ti software for thematic analysis (V. Braun & Clarke, 2006). Thematic analysis is a method of qualitative analysis that involves identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns or themes across a data set. This type of analysis is not tied to a specific theory and is compatible with various theoretical approaches (V. Braun & Clarke, 2006). For the current study, a theoretical thematic analysis was conducted rather than an inductive one. Specifically, the analysis of barriers to mental health service use was framed by Andersen’s (1995) model of health service use and stigma theory (Corrigan, 2004; Corrigan et al., 2005). Two members of the research team read all transcripts and generated initial codes. The researchers then independently coded the transcripts in Atlas.ti and met regularly to discuss the codes and reconcile differences until complete agreement was reached. Finally, the researchers sorted the codes into broader themes and checked to ensure that data within themes were consistent, and that the themes were distinguishable from one another.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Most lung cancer patients (97%, 136/140) who were approached regarding this study identified a family caregiver. Nearly all patients (96%, 131/136) permitted the research assistant to contact their caregiver. Eighty percent of caregivers agreed to be screened for psychological distress using the HADS to determine their eligibility status, 18% declined to participate, and 2% were unable to be reached via phone. Primary reasons for declining study participation were personal stress, concerns about the time commitment, and a desire to focus on patient care. Nearly half of caregivers (46%, 48/105) met the clinical cutoff (score ≥ 8) for significant anxiety or depressive symptoms on the HADS (Bjelland et al., 2002). Most eligible caregivers (96%, n = 46) consented to participate in this study.

Forty-three caregivers (93%) completed the baseline telephone assessment, and 36 caregivers completed the follow-up telephone assessment (78% retention). Reasons for study withdrawal included personal illness, patient death, concerns about the time commitment, and inability to reach the caregiver via phone. Distressed caregivers who reported non-use of mental health services at follow-up were consecutively invited to participate in the qualitative interview. All of the caregivers (n = 23) completed the interview, but data from two caregivers could not be analysed because the digital recordings were not audible. With 21 participants, the research team determined that thematic saturation had been reached. Saturation is the point at which no new narrative content codes emerge in the data analysis, and further interviews are not expected to significantly alter the content codes.

Demographic and medical characteristics of the sample appear in Table 1. Caregivers were, on average, 53 years old, married, female, Caucasian, and college-educated (mean = 15 years of education). The majority of caregivers reported an annual household income of more than $100,000, and all caregiver had health insurance. Caregivers were spouses/partners (67%) or adult children (33%) of the patient. All of the patients were diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer, and 67% had stage III or IV disease. Patients were, on average, 6 weeks from the lung cancer diagnosis at baseline. None of the caregivers were bereaved at the time of the qualitative interview.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 21).

| Variable | n (%) | Mean (SD)a | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver sex—female | 16 (76%) | ||

| Type of relationship | |||

| Spouse/partner | 14 (67%) | ||

| Adult child | 7 (33%) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 15 (71%) | ||

| African American/Black | 4 (19%) | ||

| Other | 2 (10%) | ||

| Caregiver age (years) | 53 (12) | 30 to 71 | |

| Caregiver marital status | |||

| Married or marriage equivalent | 20 (95%) | ||

| Divorced | 1 (5%) | ||

| Caregiver annual household income (median) | > $100,000 | ||

| Caregiver has health insurance | 21 (100%) | ||

| Caregiver education (years) | 15 (2) | 11 to 19 | |

| Caregiver employment status | |||

| Working full or part time | 14 (67%) | ||

| Retired | 5 (24%) | ||

| Homemaker or unemployed | 2 (10%) | ||

| Weeks since patient’s lung cancer diagnosis at baseline | 6 (5) | .14 to 15 | |

| Non-small cell lung cancer stage | |||

| Early stage (I or II) | 6 (29%) | ||

| Late stage (III or IV) | 14 (67%) | ||

| Missing | 1 (5%) | ||

| Type of lung cancer treatment | |||

| Surgery | 10 (48%) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 15 (71%) | ||

| Radiation | 7 (33%) | ||

SD = standard deviation.

Qualitative Findings

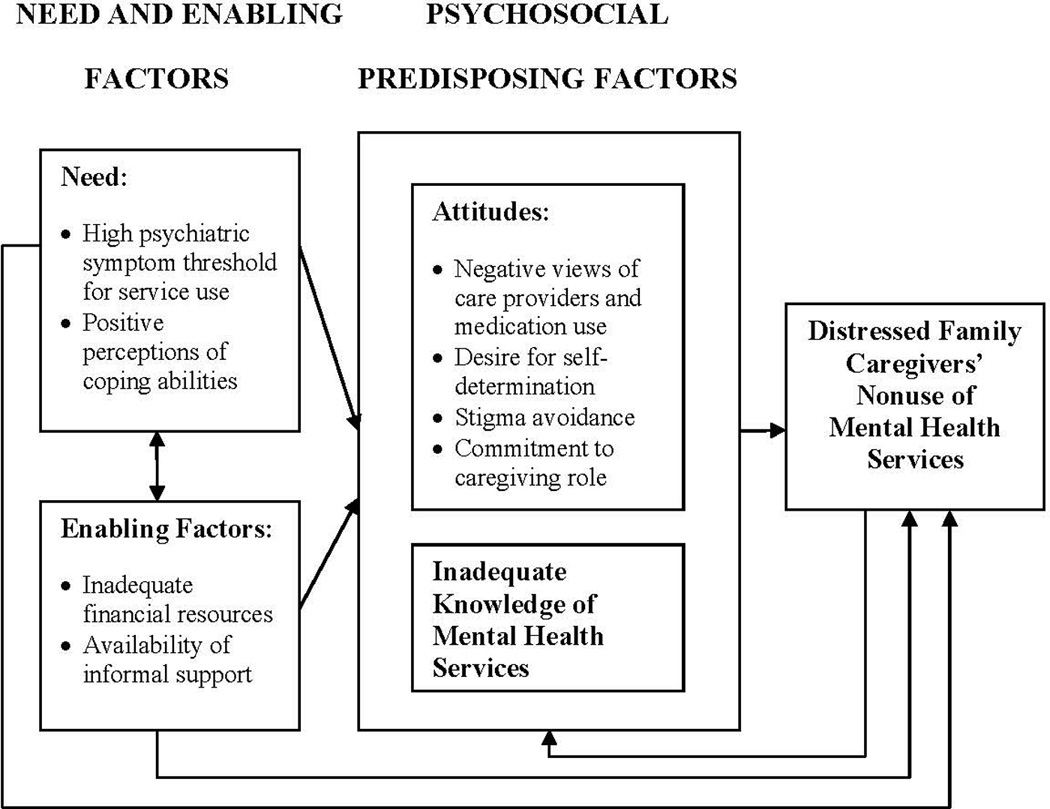

Drawing upon Andersen’s (1995) model, our thematic analysis (V. Braun & Clarke, 2006) identified three sets of interrelated factors contributing to caregivers’ decision to not seek mental health services: need (i.e., degree of psychiatric symptoms and coping abilities), enabling factors (i.e., financial resources, availability of informal support), and psychosocial predisposing factors (i.e., attitudes and knowledge of mental health services) (see Figure 1). Each of these sets of factors is described below.

Figure 1.

The role of need, enabling, and psychosocial predisposing factors in distressed family caregivers’ nonuse of mental health services

Need

Mental health service use was often characterized as a “last resort” or an option if psychosocial needs or circumstances became unbearable. For example, the wife of one patient stated that she would seek professional support if “several catastrophic events occurred simultaneously” and she was unable to cope with these events. The husband of another patient also described the point of professional help-seeking as a time of crisis: “If I am … constantly depressed or constantly angry and it’s not dissipating or I can’t pull myself out and have a positive outlook, then it is time for me to seek some type of professional help. Or any tendency to … end it all, I would have to go seek professional help.” Thus, the threshold for mental health service use for many caregivers was severe psychiatric symptoms (e.g., suicidal ideation) or an inability to manage disease and treatment-related concerns.

Enabling factors

Consistent with Andersen’s (1995) model, caregivers also identified enabling factors involved in their decision to not seek mental health services. These enabling factors included their degree of financial resources and the availability of informal support.

Financial resources

A number of caregivers noted the expense associated with mental health care when discussing reasons for their nonuse of services. As the female partner of one patient said, “there’s only so many sessions you can have through [health insurance] coverage … by the time you get ready to open up [to a therapist], the sessions are over.” She then stated her preference to discuss concerns with friends so that she can “take as much time as [she] needs.” The wife of another patient also cited expenses as a barrier to mental health service use and noted that all services would be “paid for out of pocket” until a high deductible for their insurance policy was met. Thus, although all caregivers had health insurance, their policy’s coverage of mental health services was often characterized as inadequate, and alternative nonprofessional sources of support were sought.

Availability of informal support

Many caregivers perceived their informal support system to be sufficient for coping with life’s challenges. Family members were the most frequently mentioned source of support. For example, the wife of one patient described receiving “constant phone calls” from her “tremendous support group” consisting of various family members. When asked to describe how talking to family members was helpful, the daughter of another patient said that “it either validates what I’m thinking, or they can help me think of other solutions.”

Several caregivers said that they sought assistance from family members or friends with relevant healthcare expertise. One patient’s daughter described this assistance: “one of my good friends is an oncology nurse and she was able to give me a lot of information about what my mother was going through … I felt like the more information I knew, the more control I had over the situation … so that was good for me.” Another female partner of a patient said that she received free counselling sessions from several friends who were licensed therapists. Thus, caregivers often perceived professional support seeking as unnecessary due to the receipt of support from informal sources.

Psychosocial predisposing factors

Caregivers identified two domains of psychosocial predisposing factors informing their decision to not receive mental health care: attitudes and inadequate knowledge of mental health services. Attitudes included negative views of mental health care providers and psychiatric medication use, the desire for self-determination (i.e., privacy and independence) and stigma avoidance, and commitment to the caregiving role (e.g., prioritization of the patient’s needs above their own needs). Each of these psychosocial predisposing factors is described below.

Attitudes

Care providers and medication use

A number of caregivers described mental health professionals as lacking the compassion or knowledge required to address their situation. As the wife of one patient stated, “They [mental health professionals] don’t really care. They’re not a friend … they’re detached; they’re looking at us as a number … it’s not like I’m talking to a friend or a family member that has feelings for us.” Another patient’s daughter expressed reluctance to seek counselling because the therapist would not have a “realistic view” of her family relations. A third caregiver, a patient’s wife, also voiced her lack of confidence in mental health professionals’ ability to help: “I don’t feel they can tell me anything. They could listen to me, but what could they do? I don’t want to go on any medication.”

Several caregivers stated their desire to avoid taking psychiatric medication, but only one caregiver expressed concerns about their addictive potential. Negative views of psychiatric medication and counselling did not appear to stem from personal experience with the mental health care system; in fact, nearly all prior experiences with mental health professionals were characterized as helpful.

Self-determination and stigma avoidance

As caregivers described their attitudes toward mental health services, they frequently voiced a desire for self-determination or independent management of emotional concerns, as illustrated by the following comment from a patient’s wife: “I can’t think of any [mental health] services that would help me … because I need to be in control and I need to be able to do it … I wouldn’t want somebody else doing that.” The husband of a patient expressed a similar perspective: “it’s like a roller coaster. I will be down one day and I’ll pull myself up the next day. I always feel like I can handle it myself … I will pull myself out of that depression.”

When asked to describe how they would feel if they spoke with a counsellor about their concerns, caregivers said that it would be “embarrassing” or “awkward.” The daughter of a patient summarized this perspective: “I’m not really comfortable talking about myself and my own issues … so I think I’d feel really vulnerable.” Similarly, other caregivers described mental health service use as a sign of “weakness” or “emotional fragility.” Although many caregivers anticipated negative self-perceptions and social reactions if they were to use mental health services, nearly all caregivers denied stigma associated with service use in response to direct questioning. Thus, caregivers often endorsed key aspects of internalized stigma related to mental health care (e.g., negative feelings about the self, anticipated negative reactions of others) while rejecting the term “stigma” to characterize this experience.

Several caregivers stated that their tendency to manage emotional concerns without professional support stemmed from their upbringing or cultural background. One patient’s husband who immigrated to the United States from an Asian country contrasted his upbringing with American culture: “We always feel physical health is different from mental health … you’re not supposed to be [mentally] sick. You … adjust to it yourself. But … in the United States … the cultural values are different. People don’t really think a mental health issue is weird or strange. It’s just a normal health problem.” A patient’s wife who immigrated to the United States from Europe shared a similar perspective: “in Europe you were raised to keep your opinions, your woes, your pain, your suffering … to yourself. No one else is interested.”

Caregiving role

In addition to recognizing the role of culture in their avoidance of mental health services, a number of caregivers characterized self-care as a low priority due to caregiving responsibilities. The daughter of a patient summarized this viewpoint: “I wouldn’t have ever gone to a professional because I wouldn’t want to have time away from [my mother] or the kids … it would feel too indulgent.” Similarly, two caregiving husbands shared the concern that they would be “taking time away” from their ill wives if they were to seek mental health care. Focusing on the patient’s needs to the neglect of self and showing emotional strength were viewed as expected aspects of the caregiving role.

Knowledge of mental health services

Some caregivers expressed interest in mental health services, but noted challenges in obtaining adequate information about them. This information included the location of services, the therapist’s background and credentials, and the degree to which their insurance policy covered the service. Caregivers stated that hospital staff did not provide referrals to counselling services or support groups. The daughter of a patient described an ideal referral: “if you handed me the whole tool kit and said … ‘I looked into your insurance. This is what is covered … this person deals with family members of terminally ill people with lung cancer. Here’s their number,’ I probably would call because it would all be taken care of for me.” Thus, some caregivers desired a comprehensive approach to mental health referrals.

Discussion

Family caregivers of cancer patients show high rates of psychological distress (M. Braun et al., 2007; Fridriksdóttir et al., 2011), but typically underuse mental health services (Mosher et al., 2013a; Vanderwerker et al., 2005). Thus, the present study sought to identify key barriers to mental health service use among distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients. Participating caregivers had not received mental health services during the patient’s initial months of care at a comprehensive cancer centre in the U.S., despite their widespread availability at the centre. Results of our analysis expand Andersen’s (1995) model of health service use and stigma theory (Corrigan, 2004; Corrigan et al., 2005) by providing an in-depth understanding of need, enabling, and psychosocial predisposing factors (i.e., attitudes, knowledge) associated with nonuse of mental health services in a cancer caregiving context.

Caregivers expressed several interrelated attitudes that informed their decision to not seek mental health care. Specifically, many caregivers stated a strong preference to independently manage emotional concerns. Showing this emotional strength was viewed as a normative aspect of the caregiving role. Conversely, participants characterized professional support seeking as a sign of weakness that elicited negative self-perceptions and social reactions. For example, their description of mental health service use as an “indulgent” activity that reduced time with family suggested that service use threatened their self-concept as a caregiver devoted to the patient’s needs. Interestingly, although caregivers reported key aspects of internalized stigma related to mental health service use (e.g., anticipation of negative social reactions and self-perceptions), almost all caregivers denied stigma associated with service use in response to direct questioning. In contrast, stigma has been endorsed as a barrier to mental health service use by a significant minority of people with mental illness in the U.S. (Mojtabai et al., 2011). In this study, caregivers’ denial of stigma may have been a defensive response. Alternatively, this denial may reflect cultural norms of tolerance toward mental health service use in New York City rather than expected personal consequences of service use.

Many caregivers also expressed negative opinions of mental health professionals’ ability to provide assistance. Mental health professionals were often viewed as lacking the compassion, knowledge, or skills to adequately address their situation. These results converge with evidence from population-based surveys that the perceived ineffectiveness of mental health services is a common barrier to seeking services in both clinical and non-clinical samples (Mojtabai et al., 2011; Sareen et al., 2007). Views of mental health professionals in the current sample were rarely associated with negative personal experiences with the mental health care system. In fact, many caregivers noted their limited knowledge of therapist credentials and the practical aspects of seeking mental health care.

In addition to a lack of familiarity with mental health services, caregivers noted the expense, even with health insurance coverage, and the availability of informal support as factors contributing to their decision to not seek services. Consistent with these findings, general population surveys have found that costs are a commonly perceived barrier to mental health service use in the U.S. (Mojtabai et al., 2011; Sareen et al., 2007). Reliance on other sources of support has not been assessed as a barrier to service use in national surveys, but was cited as a key reason for nonuse of a Cancer Counselling Centre by 32% of cancer patients with health insurance (Eakin & Strycker, 2001). These contextual or enabling factors may be especially relevant to understanding the mental health service use of patients and families coping with serious illness, which often impacts finances and the receipt of social support.

Given the availability of informal support and the perceived social and financial costs of seeking mental health services, caregivers frequently characterized service use as a “last resort.” Specifically, caregivers stated that severe life circumstances or psychiatric symptoms might prompt them to seek mental health services. Two potential explanations for this finding warrant further study. First, caregivers may have been avoiding internalized stigma associated with service use. Another possibility is that caregivers normalized their moderate levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms or viewed them as problems that did not require professional management. Additional research is needed to better understand laypeople’s taxonomy of mental illness and the extent to which it differs from that held by healthcare professionals.

Limitations of the present study should be noted. Although this sample was relatively diverse in terms of age, ethnic background, and patient medical characteristics (e.g., disease stage, treatments received), the majority of participants were women of middle to upper class socioeconomic status. Whether findings would generalize to men and people of lower socioeconomic status requires study. In addition, this research focused on distressed family caregivers who had not received mental health services because we were interested in barriers to service use. Conducting interviews with distressed family caregivers who received mental health services would allow us to expand our conceptual model of service use by identifying factors that facilitate service use. Furthermore, barriers to mental health service use identified in the present study should be explored in greater depth by both qualitative and quantitative research with larger sample sizes. Longitudinal data collection would allow us to gain a better understanding of factors influencing mental health care decision-making during different phases of the caregiving trajectory.

The present findings have important implications for health service use theory, especially its application to family caregivers’ mental health care decisions. First, results expand our understanding of the “beliefs” aspect of Andersen’s (1995) model of health service use. Specifically, findings suggest that negative opinions of mental health professionals, a desire for independence and privacy, and conformity to societal expectations for family caregivers (e.g., self-sacrifice) are attitudinal factors that contribute to nonuse of services among family caregivers of cancer patients. Although caregivers denied stigma associated with mental health service use, their anticipated negative self-perceptions and embarrassment if they were to use services suggest that stigma warrants further study and conceptual refinement in relation to mental health care decision-making. In the context of familial lung cancer, caregivers seeking mental health services may face stigma associated with their mental health condition as well as stigma related to their loved one’s disease. In addition, financial resources and the availability of informal support, contextual factors that often change during periods of illness, were identified as relevant to understanding family caregivers’ mental health care decisions. Finally, caregivers’ high psychiatric symptom threshold for service use points to a different taxonomy of mental illness among laypeople relative to that of professionals, which should be explored in future research.

Findings also have implications for intervention research and clinical practice. Specifically, results suggest that interventions designed to improve uptake of mental health services among distressed family caregivers may be more effective if prior knowledge of services is assessed and misconceptions of mental health professionals are addressed. In addition, such interventions would address practical aspects of service use (e.g., costs) and target self-perceptions associated with service use. For example, the belief that mental health service use is a sign of weakness could be discussed. This process of mental health referral may be integrated into assessments conducted by oncologists, nurses, and other healthcare professionals. Another important direction for future research and practice is designing more palatable services for caregivers that overcome practical barriers to service use. Specifically, technology-based interventions may help reduce stigma and expenses associated with service use and improve the reach of services to those with family caregiving responsibilities.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Grant No. R03CA139862 from the National Cancer Institute. CM was supported by F32CA130600 from the National Cancer Institute and KL2 RR025760 (A. Shekhar, PI) from the National Center for Research Resources. P30CA008748 supported the Behavioral Research Methods Core Facility used in conducting this investigation. The authors would like to thank the study participants, the thoracic oncology team at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and Heather A. Jaynes, Elyse Shuk, and Scarlett Ho for their assistance.

Contributor Information

Catherine E. Mosher, Department of Psychology, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, 402 North Blackford Street, LD 124, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA, Phone: 1-317-274-6769, Fax: 1-317-274-6756, cemosher@iupui.edu.

Barbara A. Given, University Distinguished Professor, College of Nursing, Michigan State University, 1355 Bogue Street, Room C383, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA, Phone: 1-517-342-3872, Fax: 1-517-353-8612, Barb.Given@hc.msu.edu

Jamie S. Ostroff, Behavioral Science Service, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 641 Lexington Avenue, 7th Floor, New York, NY 10022, USA, Phone: 1-646-888-0041, Fax: 1-212-888-2584, ostroffj@mskcc.org.

References

- Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;52:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum K, Sherman DW. Understanding the experience of caregivers: A focus on transitions. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2010;26:243–258. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M, Mikulincer M, Rydall A, Walsh A, Rodin G. Hidden morbidity in cancer: Spouse caregivers. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:4829–4834. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Choi CW, Stone RA, Kim KH, Ren D, Schulz R, Given CW, Given BA, Sherwood PR. Group-based trajectory modeling of caregiver psychological distress over time. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;44:73–84. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9371-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AE, Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Mental illness stigma and care seeking. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2003;191:339–341. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000066157.47101.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW. How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist. 2004;59:614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Kerr A, Knudsen L. The stigma of mental illness: Explanatory models and methods for change. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 2005;11:179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Barr L. The self-stigma of mental illness: Implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:875–884. [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra SS, Zack M, Strine T, Pearson WS, Balluz L. Determining prevalence and correlates of psychiatric treatment with Andersen's behavioral model of health services use. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:524–528. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.5.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eakin EG, Strycker LA. Awareness and barriers to use of cancer support and information resources by HMO patients with breast, prostate, or colon cancer: patient and provider perspectives. Psycho-Oncology. 2001;10:103–113. doi: 10.1002/pon.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Downs MF, Golberstein E, Zivin K. Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Medical Care Research and Review. 2009;66:522–541. doi: 10.1177/1077558709335173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Ford JD. Correlates of mental health service use intensity in the National Comorbidity Survey and National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:1108–1115. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.8.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridriksdóttir N, Saevarsdóttir T, Halfdánardóttir SI, Jónsdóttir A, Magnúsdóttir H, Ólafsdóttir KL, Guethmundsdóttir G, Gunnarsdóttir S. Family members of cancer patients: Needs, quality of life and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Acta Oncologica. 2011;50:252–258. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.529821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbins J, McCoubrie R, Kendrick AH, Senior-Smith G, Davies AN, Hanks GW. Sleep-wake disturbances in patients with advanced cancer and their family carers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2009;38:860–870. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golberstein E, Eisenberg D, Gollust SE. Perceived stigma and help-seeking behavior: longitudinal evidence from the healthy minds study. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:1254–1256. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.9.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Given BA. Quality of life of family caregivers of cancer survivors: across the trajectory of the illness. Cancer. 2008;112:2556–2568. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SD, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C, Stacey F. Walking a mile in their shoes: anxiety and depression among partners and caregivers of cancer survivors at 6 and 12 months post-diagnosis. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21:75–85. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1495-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SD, Jones BL, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C. Distressed partners and caregivers do not recover easily: adjustment trajectories among partners and caregivers of cancer survivors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;44:225–235. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JD, Boyd JE. Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;71:2150–2161. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobchuk MM, Murdoch T, McClement SE, McPherson C. A dyadic affair: who is to blame for causing and controlling the patient's lung cancer? Cancer Nursing. 2008;31:435–443. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000339253.68324.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milbury K, Badr H, Carmack CL. The role of blame in the psychosocial adjustment of couples coping with lung cancer. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;44:331–340. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9402-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Sampson NA, Jin R, Druss B, Wang PS, Wells KB, Pincus HA, Kessler RC. Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:1751–1761. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher CE, Champion VL, Hanna N, Jalal SI, Fakiris AJ, Birdas TJ, Okereke IC, Kesler KA, Einhorn LH, Given BA, Monahan PO, Ostroff JS. Support service use and interest in support services among distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2013a;22:1549–1556. doi: 10.1002/pon.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher CE, Jaynes HA, Hanna N, Ostroff JS. Distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients: An examination of psychosocial and practical challenges. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013b;21:431–437. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1532-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving. National Alliance for Caregiving: Caregiving in the U.S., 2009. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.caregiving.org/data/Caregiving_in_the_US_2009_full_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Northouse L, Williams AL, Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:1227–1234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Wassel A, Michaels P, Larson JE, Olschewski M, Wilkniss S, Batia K. Self-stigma, group identification, perceived legitimacy of discrimination and mental health service use. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;195:551–552. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.067157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Jagdeo A, Cox BJ, Clara I, ten Have M, Belik SL, de Graaf R, Stein MB. Perceived barriers to mental health service utilization in the United States, Ontario, and the Netherlands. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:357–364. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro SG, Douse J, Read C, Janes S. Complications of lung cancer treatment. Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2008;29:302–317. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1076750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C, Morris SM, Harman JC. Companions through cancer: the care given by informal carers in cancer contexts. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;54:529–544. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwerker LC, Laff RE, Kadan-Lottick NS, McColl S, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric disorders and mental health service use among caregivers of advanced cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:6899–6907. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel DL, Wade NG, Haake S. Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53:325–337. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Augustson E, Atienza AA. Smoking concordance in lung and colorectal cancer patient-caregiver dyads and quality of life. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2011;20:239–248. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JL, Dy SM, Frick KD, Kasper JD. End-of-life care: Findings from a national survey of informal caregivers. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:40–46. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]