Abstract

Liver resection is the gold standard treatment for certain liver tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma and metastatic liver tumors. Some patients with such tumors already have reduced liver function due to chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, or chemotherapy-associated steatohepatitis before surgery. Therefore, complications due to poor liver function are inevitable after liver resection. Although the mortality rate of liver resection has been reduced to a few percent in recent case series, its overall morbidity rate is reported to range from 4.1% to 47.7%. The large degree of variation in the post-liver resection morbidity rates reported in previous studies might be due to the lack of consensus regarding the definitions and classification of post-liver resection complications. The Clavien-Dindo (CD) classification of post-operative complications is widely accepted internationally. However, it is hard to apply to some major post-liver resection complications because the consensus definitions and grading systems for post-hepatectomy liver failure and bile leakage established by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery are incompatible with the CD classification. Therefore, a unified classification of post-liver resection complications has to be established to allow comparisons between academic reports.

Keywords: Complication, Liver failure, Bile leakage, Renal failure, Ascites, Coagulation disorder, Surgical site infection

Core tip: The large degree of variation in the post-liver resection morbidity rates reported by previous studies might be due to a lack of consensus regarding the definitions and classification of post-liver resection complications. The Clavien-Dindo classification of postoperative complications is widely accepted internationally. However, it is difficult to apply to some major post-liver resection complications. Therefore, a unified classification of post-liver resection complications has to be established to allow comparisons between academic reports.

INTRODUCTION

Liver resection has become a safe operation, and its mortality rate is now almost zero, which is much lower than the rate seen a decade ago[1-3]. Liver resection is the best curative option for patients with certain types of liver cancer such as hepatocellular carcinoma[4,5] and metastatic liver cancer[6], as it is cost effective and results in a shorter period of disease-related suffering. To reduce the invasiveness of surgery, laparoscopic procedures have been widely adopted for various types of liver resection[2,7-9]. Preliminary clinical studies have demonstrated that compared with open surgery laparoscopic liver resection results in fewer surgical complications, less intraoperative bleeding, and shorter hospital stays whilst achieving similar oncological outcomes[2,10].

Although the mortality rates described by previous studies were similar, the reported post-liver resection morbidity rates varied markedly due to the use of different definitions for each complication. In fact, the overall morbidity rate of open liver surgery has been reported to range from 4.1% to 47.7%[2,11]. Dindo et al[12] attempted to unify the definitions of post-liver resection surgical complications by developing their own grading system (Table 1), which has been widely accepted according to surgical academic reports. However, a classification of the complications seen after hepatobiliary surgery produced by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS)[13] was incompatible with the definitions outlined in Clavien’s classification. For example, cases that involve surgical or radiological interventions performed under general anesthesia (categorized as IIIb under the Clavien-Dindo classification) are rarely seen in the clinical setting. Furthermore, patients who suffer organ failure usually exhibit multiple complications, and thus, it is difficult to identify a single cause of the organ failure.

Table 1.

Comparison between the modified grading system and the Clavien-Dindo classification

| Modified grades | Clavien-Dindo classification | |

| Grade A | GradeI | Any deviation from the normal postoperative course that did not require special treatment |

| Grade II | Cases requiring pharmacological treatment | |

| Grade B | Grade IIIa | Cases requiring surgical or radiological interventions without general anesthesia |

| Grade C | Grade IIIb | Cases requiring surgical or radiological interventions performed under general anesthesia |

| Grade IVa | Life-threatening complications involving single organ dysfunction | |

| Grade D | Grade IVb | Life-threatening complications involving multiple organ dysfunction |

| Grade V | Cases that resulted in death |

Therefore, we reviewed the definitions of post-liver resection surgical complications and have developed a simple grading and classification system to allow academic reports to be compared.

POST-HEPATECTOMY LIVER FAILURE

Liver failure is the most serious complication after liver resection and can be life-threatening[14,15]. The etiologies of post-hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) include a small remnant liver[16], vascular flow disturbance[17], bile duct obstruction[15], drug-induced injury[18], viral reactivation[19], and severe septic conditions[15]. In 2011, the ISGLS defined PHLF as a postoperative reduction in the ability of the liver to maintain its synthetic, excretory, and detoxifying functions, which is characterized by an increased international normalized ratio and concomitant hyperbilirubinemia on or after postoperative day 5[13]. Treatments for PHLF must be selected carefully based on the etiology of the condition. Since it was proposed, most reports have employed the ISGLS definitions of PHLF (Table 2). In addition to the latter definitions, our grading system also includes information about the management strategies that are typically employed to treat each PHLF grade (Table 2).

Table 2.

Grading system and representative management strategies for post-hepatectomy liver failure

| Grades | Definition | Management strategies |

| Grade A | No change in the patient’s clinical management strategy required or manageable with medication | Diuretics, selective digestive decontamination, lactulose, glucagon-insulin therapy, stronger neo-minophagen C |

| Grade B | Manageable without invasive treatment | FFP transfusion, hyperbaric oxygen therapy |

| Grade C | Invasive treatment required | Plasma exchange, artificial liver support, surgery (including liver transplantation) |

Artificial liver support is including high-flow hemodialysis with FFP transfusion. FFP: Fresh frozen plasma.

BILE LEAKAGE

Bile leakage (BL) is a major complication of liver resection. The incidence of BL is reported to be 4.0% to 17%[20], and a previous meta-analysis did not find any difference in the incidence of BL between open and laparoscopic cases[21]. BL is defined as an increased bilirubin concentration in the drain or intra-abdominal fluid; i.e., a bilirubin concentration at least 3 times greater than the simultaneously measured serum bilirubin concentration[22]. Once BL develops, it can sometimes lead to complications and can become difficult to manage without interventional radiology (IVR). One of our representative Grade C cases is shown in Figure 1. BL is usually managed with extensive IVR, and reoperations are rarely required. The ISGLS has also developed a grading system for BL[22]. Although the different grades of PHLF are well defined based on clinical symptoms and the management strategies employed, the definitions of each BL grade are too subjective. Therefore, our grading system includes clinical examples (Table 3).

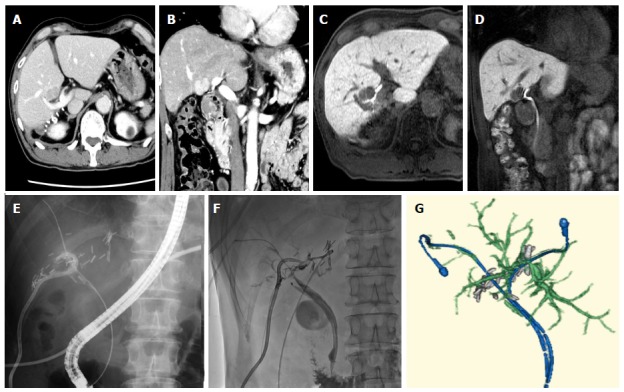

Figure 1.

Representative grade C case in bile leakage. A 67-year-old man had hepatocellular carcinoma (diameter: 2 cm; A: Axial view; B: Coronal view) in segment S5 of his liver (located at the bifurcation of the bile duct in the hilar plate) (C: Axial view; D: Coronal view). The tumor was resected via enucleation; E: Bile leakage was detected and so endoscopic retrograde cholangiodrainage was performed together with percutaneous drainage of the resected pouch; F: Subsequently, stenosis of the left hepatic duct due to bile duct ischemia occurred. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiodrainage was performed via the B3 duct; G: Three-dimensional reconstruction based on CT images obtained before the patient was discharged from hospital. CT: Computed tomography.

Table 3.

Grading system and representative management strategies for bile leakage

| Grades | Definition | Management strategies |

| Grade A | No change in the patient’s clinical management strategy required or manageable with simple drainage | Drainage within 7 d Antibiotic administration |

| Grade B | Manageable with interventional procedures | Drainage for 7 or more day, ethanol injection, fibrin paste injection, single ENBD, single EBD, single PTBD, PTPE, TAE |

| Grade C | Cases involving pneumoperitoneum, inflammation, multiple organ failure, or reoperation | Complicated IVR (combinations with any Grade Bs) Reoperation |

ENBD: Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage; EBD: Andoscopic biliary drainage; PTBD: Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage; PTPE: Percutaneous transcatheter portal embolization; TAE: Transcatheter arterial embolization; IVR: Interventional radiology.

ACUTE RENAL FAILURE

Acute renal failure (ARF) is associated with various postoperative complications. Renal failure is closely associated with PHLF and can lead to hepatorenal syndrome (HRS). The International Ascites Club (IASC) defined HRS using the following criteria[23-25]: (1) cirrhosis and ascites are present; (2) the patient’s serum creatinine level is greater than 1.5 mg/dL (or 133 mmol/L); (3) no sustained improvement in the serum creatinine level (to a level of 1.5 mg/dL or less) is seen at least 48 h after diuretic withdrawal and volume expansion with albumin (recommended dose: 1 g/kg body weight per day up to a maximum of 100 g of albumin/d); (4) shock is absent; (5) the patient is not currently taking nor have they recently been taking nephrotoxic drugs; (6) parenchymal kidney disease, as indicated by proteinuria of greater than 500 mg/d, microhematuria ( > 50 red blood cells/high power field), and/or abnormal renal ultrasonography, is absent (Verna EC1, Wagener G, Renal interactions in liver dysfunction and failure).

On the other hand, post-liver resection ARF is still poorly defined. Therefore, we have proposed a grading system for post-liver resection ARF (Table 4). The management of ARF mainly involves dehydration and the use of diuretics[26]. Most cases of Grade A and Grade B ARF are reversible and manageable via the latter approach. We defined cases in which the patient could not pass urine without continuous diuretic use as Grade B. On the other hand, Grade C cases were defined as those in which the patient required hemodialysis.

Table 4.

Grading system and representative management strategies for acute renal failure

| Grades | Definition | Management strategies |

| Grade A | Increase in serum creatinine level of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL from the baseline or 1.5 to 2-fold increase from the baseline | Dehydration |

| Urinary output of less than 0.5 mL/kg per hour for more than 6 h | Diuretics | |

| Grade B | Two-fold increase in the serum creatinine level from the baseline | Continuous mannitol + diuretics |

| Urinary output of less than 0.5 mL/kg per hour for more than 12 h | ||

| Grade C | Dialysis treatment required (serum K > 6.0 mEq, BE < -10, uremia, hypouresis that lasts for more than three days) | Hemodialysis |

ASCITES

Ascites is a common complication in patients who exhibit liver dysfunction or cirrhosis after liver resection[27]. One of the possible pathogenic mechanisms of the ascites seen after liver resection is portal flow resistance at the sinusoidal level due to a reduction in the volume of the portal vascular bed[28]. Hepatic outflow block can also cause increased portal flow resistance[29]. The acute phase after liver resection tends to involve edema in the interstitial organ space, which leads to increased portal flow resistance. The management of ascites after liver resection focuses on decreasing the patient’s portal pressure[27,28]. The use of diuretics or sodium restriction can decrease systemic flow volume, and ascites can also be controlled by decreasing edema in the inter-organ space or establishing a systemic shunt. Invasive management aims to decrease the patient’s portal pressure through mechanical interventions. The IASC previously released statements containing revised definitions of ascites (Table 5); however, they were too abstract to use in academic studies. So, we proposed a modified grading system for post-operative ascites after liver resection (Table 6).

Table 5.

Grading system and representative management strategies for ascites

| Grades | Definition in International Ascites Club (2003) | Definition in International Ascites Club (1996) |

| Grade A | Detected only on United States | Mild |

| Grade B | Moderate symmetrical distention of the abdomen | Moderate |

| Grade C | Marked abdominal distention | Massive or tense |

Table 6.

Grading system and representative management strategies for ascites

| Grades | Definition | Management strategies |

| Grade A | Requiring any changes in the clinical management strategy or manageable with medication | Diuretics, sodium restriction |

| Ascites discharge < 1000 mL/d in the drainage case | ||

| Grade B | Grade A ascites that lasts for more than 2 wk or requires peritoneal puncture | Peritoneal puncture |

| Ascites discharge < 2000 mL/d in the drainage case | ||

| Grade C | Invasive treatment required | Denver peritoneovenous shunt, TIPS, PSE, splenectomy |

TIPS: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; PSE: Partial splenic embolization.

SURGICAL SITE INFECTIONS (SUPERFICIAL, ORGAN AND DEEP) AND WOUND DEHISCENCE

Surgical site infections (SSI) are common after all types of surgery and are classified into superficial, deep incisional, and organ/space SSI. Although several classifications of SSI have been proposed[30], the definitions developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are widely used internationally[31]. According to the CDC, SSI are infections that occur within 30 d of surgery or within one year if an implant is present[31]. In addition, one of the following criteria must be met: (1) purulent drainage from an incision (incisional infection) or from a drain below the fascia (deep infection); (2) a surgeon or attending physician diagnosing an SSI; (3) an infective organism being isolated from a culture of fluid or tissue obtained from the surgical wound (for incisional infections); (4) spontaneous dehiscence or a surgeon deliberately re-opening the wound in the presence of fever or local pain, unless subsequent cultures were negative, or an abscess being detected during direct examinations (for deep infections). However, the grading of SSI based on symptoms and the management strategy employed is difficult. Therefore, we proposed that SSI should be graded based on how long they take to cure (Table 7 for superficial SSI and wound dehiscence, Table 8 for deep and organ/space SSI). Using this new grading system, it is very easy and simple to grade SSI objectively.

Table 7.

Grading system for superficial SSI and wound dehiscence

| Grades | Definitions | Management strategies |

| Grade A | Manageable within 2 wk | Small open wound, outpatient service |

| Grade B | Requiring any management 2 wk and more | Large open wound, inpatient service |

| Grade C | Any management required under general anesthesia |

Table 8.

Grading system for deep and organ/space surgical site infections

| Grades | Definitions | Management strategies |

| Grade A | Manageable without requiring any additional perioperative management within 2 wk | Antibiotics, simple drainage |

| Grade B | Requiring any management 2 wk and more | Additional drainage, irrigation |

| Grade C | Any management required under general anesthesia |

COAGULATION DISORDERS

Coagulation disorders are a common complication after liver resection[32,33]. Most coagulation and anti-coagulant factors are synthesized by the liver, and the ability to synthesize such factors rapidly deteriorates after liver resection in cirrhotic patients and those who experience marked hepatic volume loss[20]. In addition, most patients who are scheduled to undergo liver resection present with thrombocytopenia due to portal hypertension. Therefore, a prolonged prothrombin time, a prolonged thrombin time, elevated levels of fibrinogen degradation products, and a low platelet count are common after liver resection[34]. As we have mentioned in the ascites section, portal hypertension can occur after liver resection due to an increase in portal flow resistance[17]. Therefore, coagulation disorders should be divided into two different grades based on whether the patient displays normal or abnormal preoperative platelet levels (Table 9).

Table 9.

Grading system and representative management strategies for coagulation disorders

| Grades | Definition | Managements |

| Grade A | Does not require any change in the clinical management strategy | Vitamin K, ATIII, LMWH, SPI, UFH, and DS |

| Plat < 10 × 104 (preoperative Plat was within normal range) | ||

| 30% reduction in Plat (preoperative Plat was abnormal) | ||

| Grade B | Medication required for more than 5 d | Platelet transfusion |

| Plat < 5 × 104 (preoperative Plat was within normal range) | ||

| 60% reduction in Plat (preoperative Plat was abnormal) | ||

| Grade C | Intensive care treatment required and involved the failure of other organs |

Plat: Platelet count; ATIII: Anti-thrombin; LMWH: Low molecular weight heparin; SPI: Synthetic protease inhibitor; UFH: Unfractionated heparin; DS: Danaparoid sodium.

PNEUMONIA AND RESPIRATORY DISORDER

Postoperative pneumonia and respiratory disorder (PPN/RD) was rarely seen after liver resection recently except in the elderly cases[35,36]. Definition of the PPN/RD was shown in Table 10. Clinical sign of the PPN/RD is systemic inflammatory response syndrome with any radiological imaging findings[37]. Management will be taken by administrating susceptible anti-biotics with oxygen supply. Acute lung injury (ALI) is defined by PaO2/FiO2 ratios < 300 and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is defined by PaO2/FiO2 ratios < 200[38]. In our grading, ALI is in Grade A and ARDS is in the grade B (Table 10). Our grading is not only defined PPN/RD after liver resection but also after other general surgery.

Table 10.

Grading system and representative management strategies for pneumonia and respiratory disorder

| Grades | Definition | Managements |

| Grade A | Meet SIRS criteria with imaging findings in less than 50% of the lung field or PaO2/FiO2 < 300 | Antibiotics and oxygen |

| Sputum suction | ||

| Grade B | Meet SIRS criteria with imaging findings in 50% and more of the lung field or PaO2/FiO2 < 200 | Antibiotics and oxygen, IPPV, NPPV, bronchoscopy for sputum suction |

| Grade C | Requiring ventilator support | Ventilator |

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria is defined as two or more of the following clinical signs: bodily temperature > 38 °Cor < 36 °C, heart rate > 90/min, respiratory rate > 20 /min or PaCO2 < 32 mmHg, WBC > 12000/μL or < 4000 /μL or immature cells > 10%. Pneumonia imaging is any of airspace opacity, lobar consolidation, or interstitial opacities. SIRS: Systemic inflammatory response syndrome; IPPV: Intermittent positive-pressure breathing; NPPV: Nasal positive-pressure ventilation.

CONCLUSION

The complications seen after liver resection are different from those encountered after other types of surgery because the liver produces most serum proteins, which play a major role in maintaining systemic homeostasis, and liver resection affects liver function. Therefore, post-liver resection complications tend to be severe. The risk factors for complications after liver resection depend on the pathological background of the liver itself[39]. In patients with normal liver function, the operative time, fresh frozen plasma transfusion requirement, tumor size, and retinol binding protein levels are independent risk factors for complications[40]. On the other hand, the PT and the indocyanine green retention value at 15 min are independent risk factors for complications in cirrhotic patients[40]. Therefore, consensus definitions and grading systems are necessary to allow comparisons between academic reports. Our grading system incorporates established consensus definitions and statements, such as those for PHLF and BL, and attempts to establish objective definitions for grading other complications. We hope that our grading system will be used to describe the complications experienced after liver resection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ms. Ayaka Saigo for her help with this article.

Footnotes

Supported by A Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (No. 26461921) to T. Mizuguchi, (No. 26461920) to M, Meguro and (No. 25861207) to S. Ota

P- Reviewer: Inoue K, Roller J S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Delis SG, Madariaga J, Bakoyiannis A, Dervenis Ch. Current role of bloodless liver resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:826–829. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i6.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizuguchi T, Kawamoto M, Meguro M, Shibata T, Nakamura Y, Kimura Y, Furuhata T, Sonoda T, Hirata K. Laparoscopic hepatectomy: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and power analysis. Surg Today. 2011;41:39–47. doi: 10.1007/s00595-010-4337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asiyanbola B, Chang D, Gleisner AL, Nathan H, Choti MA, Schulick RD, Pawlik TM. Operative mortality after hepatic resection: are literature-based rates broadly applicable? J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:842–851. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0494-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu KT, Wang CC, Lu LG, Zhang WD, Zhang FJ, Shi F, Li CX. Hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical study of long-term survival and choice of treatment modalities. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3649–3657. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i23.3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fong ZV, Tanabe KK. The clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States, Europe, and Asia: A comprehensive and evidence-based comparison and review. Cancer. 2014;120:2824–2838. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang P, Chen Z, Huang WX, Liu LM. Current preventive treatment for recurrence after curative hepatectomy for liver metastases of colorectal carcinoma: a literature review of randomized control trials. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3817–3822. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i25.3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buell JF, Cherqui D, Geller DA, O’Rourke N, Iannitti D, Dagher I, Koffron AJ, Thomas M, Gayet B, Han HS, et al. The international position on laparoscopic liver surgery: The Louisville Statement, 2008. Ann Surg. 2009;250:825–830. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e3181b3b2d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simillis C, Constantinides VA, Tekkis PP, Darzi A, Lovegrove R, Jiao L, Antoniou A. Laparoscopic versus open hepatic resections for benign and malignant neoplasms--a meta-analysis. Surgery. 2007;141:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Croome KP, Yamashita MH. Laparoscopic vs open hepatic resection for benign and malignant tumors: An updated meta-analysis. Arch Surg. 2010;145:1109–1118. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaillard M, Tranchart H, Dagher I. Laparoscopic liver resections for hepatocellular carcinoma: current role and limitations. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4892–4899. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i17.4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spolverato G, Ejaz A, Hyder O, Kim Y, Pawlik TM. Failure to rescue as a source of variation in hospital mortality after hepatic surgery. Br J Surg. 2014;101:836–846. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahbari NN, Garden OJ, Padbury R, Brooke-Smith M, Crawford M, Adam R, Koch M, Makuuchi M, Dematteo RP, Christophi C, et al. Posthepatectomy liver failure: a definition and grading by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS) Surgery. 2011;149:713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernal W, Wendon J. Acute liver failure. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2525–2534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcea G, Maddern GJ. Liver failure after major hepatic resection. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:145–155. doi: 10.1007/s00534-008-0017-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pulitano C, Crawford M, Joseph D, Aldrighetti L, Sandroussi C. Preoperative assessment of postoperative liver function: the importance of residual liver volume. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:445–450. doi: 10.1002/jso.23671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nobuoka T, Mizuguchi T, Oshima H, Shibata T, Kimura Y, Mitaka T, Katsuramaki T, Hirata K. Portal blood flow regulates volume recovery of the rat liver after partial hepatectomy: molecular evaluation. Eur Surg Res. 2006;38:522–532. doi: 10.1159/000096292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leise MD, Poterucha JJ, Talwalkar JA. Drug-induced liver injury. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kubo S, Nishiguchi S, Hamba H, Hirohashi K, Tanaka H, Shuto T, Kinoshita H, Kuroki T. Reactivation of viral replication after liver resection in patients infected with hepatitis B virus. Ann Surg. 2001;233:139–145. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200101000-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin S, Fu Q, Wuyun G, Wuyun T. Management of post-hepatectomy complications. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7983–7991. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i44.7983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiong JJ, Altaf K, Javed MA, Huang W, Mukherjee R, Mai G, Sutton R, Liu XB, Hu WM. Meta-analysis of laparoscopic vs open liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6657–6668. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i45.6657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koch M, Garden OJ, Padbury R, Rahbari NN, Adam R, Capussotti L, Fan ST, Yokoyama Y, Crawford M, Makuuchi M, et al. Bile leakage after hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: a definition and grading of severity by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery. Surgery. 2011;149:680–688. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verna EC, Wagener G. Renal interactions in liver dysfunction and failure. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2013;19:133–141. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32835ebb3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angeli P, Sanyal A, Moller S, Alessandria C, Gadano A, Kim R, Sarin SK, Bernardi M. Current limits and future challenges in the management of renal dysfunction in patients with cirrhosis: report from the International Club of Ascites. Liver Int. 2013;33:16–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2012.02807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lata J. Hepatorenal syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4978–4984. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i36.4978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitra A, Zolty E, Wang W, Schrier RW. Clinical acute renal failure: diagnosis and management. Compr Ther. 2005;31:262–269. doi: 10.1385/comp:31:4:262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senousy BE, Draganov PV. Evaluation and management of patients with refractory ascites. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:67–80. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salerno F, Guevara M, Bernardi M, Moreau R, Wong F, Angeli P, Garcia-Tsao G, Lee SS. Refractory ascites: pathogenesis, definition and therapy of a severe complication in patients with cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2010;30:937–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kubota K, Makuuchi M, Takayama T, Harihara Y, Watanabe M, Sano K, Hasegawa K, Kawarasaki H. Successful hepatic vein reconstruction in 42 consecutive living related liver transplantations. Surgery. 2000;128:48–53. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.106783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson AP. Postoperative surveillance, registration and classification of wound infection in cardiac surgery--experiences from Great Britain. APMIS. 2007;115:996–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13:606–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stellingwerff M, Brandsma A, Lisman T, Porte RJ. Prohemostatic interventions in liver surgery. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2012;38:244–249. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1302440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan FS, Ng SY, Ho KY, Lee SY, Chung AY, Poopalalingam R. Abnormal coagulation profile after hepatic resection: the effect of chronic hepatic disease and implications for epidural analgesia. J Clin Anesth. 2012;24:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ben-Ari Z, Osman E, Hutton RA, Burroughs AK. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in liver cirrhosis: fact or fiction? Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2977–2982. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koperna T, Kisser M, Schulz F. Hepatic resection in the elderly. World J Surg. 1998;22:406–412. doi: 10.1007/s002689900405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirokawa F, Hayashi M, Miyamoto Y, Asakuma M, Shimizu T, Komeda K, Inoue Y, Takeshita A, Shibayama Y, Uchiyama K. Surgical outcomes and clinical characteristics of elderly patients undergoing curative hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1929–1937. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelly E, MacRedmond RE, Cullen G, Greene CM, McElvaney NG, O’Neill SJ. Community-acquired pneumonia in older patients: does age influence systemic cytokine levels in community-acquired pneumonia? Respirology. 2009;14:210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raghavendran K, Napolitano LM. Definition of ALI/ARDS. Crit Care Clin. 2011;27:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mizuguchi T, Nagayama M, Meguro M, Shibata T, Kaji S, Nobuoka T, Kimura Y, Furuhata T, Hirata K. Prognostic impact of surgical complications and preoperative serum hepatocyte growth factor in hepatocellular carcinoma patients after initial hepatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:325–333. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0711-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mizuguchi T, Kawamoto M, Meguro M, Nakamura Y, Ota S, Hui TT, Hirata K. Prognosis and predictors of surgical complications in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with or without cirrhosis after hepatectomy. World J Surg. 2013;37:1379–1387. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-1989-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]