Abstract

AIM: To evaluate Quality of life (QoL) in chronic heart failure (CHF) in relation to Neuroticism personality trait and CHF severity.

METHODS: Thirty six consecutive, outpatients with Chronic Heart Failure (6 females and 30 males, mean age: 54 ± 12 years), with a left ventricular ejection fraction ≤ 45% at optimal medical treatment at the time of inclusion, were asked to answer the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) for Quality of Life assessment and the NEO Five-Factor Personality Inventory for personality assessment. All patients underwent a symptom limited cardiopulmonary exercise testing on a cycle-ergometer, in order to access CHF severity. A multivariate linear regression analysis using simultaneous entry of predictors was performed to examine which of the CHF variables and of the personality variables were correlated independently to QoL scores in the two summary scales of the KCCQ, namely the Overall Summary Scale and the Clinical Summary Scale.

RESULTS: The Neuroticism personality trait score had a significant inverse correlation with the Clinical Summary Score and Overall Summary Score of the KCCQ (r = -0.621, P < 0.05 and r = -0.543, P < 0.001, respectively). KCCQ summary scales did not show significant correlations with the personality traits of Extraversion, Openness, Conscientiousness and Agreeableness. Multivariate linear regression analysis using simultaneous entry of predictors was also conducted to determine the best linear combination of statistically significant univariate predictors such as Neuroticism, VE/VCO2 slope and VO2 peak, for predicting KCCQ Clinical Summary Score. The results show Neuroticism (β = -0.37, P < 0.05), VE/VCO2 slope (β = -0.31, P < 0.05) and VO2 peak (β = 0.37, P < 0.05) to be independent predictors of QoL. In multivariate regression analysis Neuroticism (b = -0.37, P < 0.05), the slope of ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide output during exercise, (VE/VCO2 slope) (b = -0.31, P < 0.05) and peak oxygen uptake (VO2 peak), (b = 0.37, P < 0.05) were independent predictors of QoL (adjusted R2 = 0.64; F = 18.89, P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: Neuroticism is independently associated with QoL in CHF. QoL in CHF is not only determined by disease severity but also by the Neuroticism personality trait.

Keywords: Chronic heart failure, Five-Factor Personality Inventory, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, Quality of Life

Core tip: Of the patients with chronic heart failure (CHF), those who are experiencing low Quality of Life (QoL) show higher morbidity, hospitalization rates and mortality. There is a link between low QoL, low adherence to pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical treatment as well as exercise training rehabilitation, and high anxiety and depression levels. The personality of the patient has been also found to play a role in affecting QoL and therefore prognosis. Taking into account that the personality trait of Neuroticism, has been found to affect QoL in chronically ill individuals, this study explores its possible role in predicting QoL in CHF population in relation to disease severity.

INTRODUCTION

The quantification of patients’ Quality of life (QoL) is becoming a useful endpoint in the study of chronic heart failure (CHF), not only as a marker of health care quality, but also as a tool for monitoring patients over time[1,2]. The evaluation of patients’ QoL as well as of factors that are pertinent to it are considered as important for the prognosis in CHF, as QoL has been shown to identify patients with more severe syndrome[3-6] and at greater risk for hospitalization or death[7-9]. QoL is closely related to exercise intolerance, and exercise capacity improvement by exercise training in CHF improved QoL and reduced mortality and cardiac events[10,11]. Furthermore, QoL in CHF has been associated with psychological factors such as depression, anxiety and personality. Depressed as well as anxious CHF patients were found to have poor QoL[12], with depression being a strong predictor of QoL even after adjustment with disease severity[13].

However the role of personality in the QoL of CHF has been largely overlooked, as most studies have focused on the role of depression and anxiety as the main psychological determinants. The personality trait that has been most widely studied in CHF population is type-D, which was found to be independently associated with impaired QoL in CHF[14], anxiety and depression[15], and increased mortality[16]. Another well documented personality trait, Neuroticism, has been demonstrated to affect QoL in chronically ill individuals as well as to be correlated with increased levels of anxiety and depression[17-21]. However, there have been only a few reports indicating a possible role of Neuroticism to predict QoL[22] and prognosis in CHF patients[23,24].

Therefore, the personality trait of Neuroticism constitutes an interesting but yet not well explored factor in the relationship between personality and QoL in patients with CHF. The aim of this study is to investigate the role of Neuroticism in QoL in CHF in relation to CHF severity. We hypothesized that Neuroticism affects QoL in patients with stable CHF, independently of the disease severity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The study population consisted of 36 consecutive stable CHF outpatients (6 women and 30 men), with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 45% at optimal medical treatment at the time of inclusion, who were referred to our laboratory from the Heart Failure Clinic of the Medical School of the University of Athens, during the years 2008-2009, in order to perform a symptom-limited cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET), as a part of heart failure evaluation.

Patients were excluded from the study if there was any contraindication for a CPET according to the American Thoracic Society/American College of Chest Physicians Statement on CPET[25] and if there was a history of moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or cancer disease or other systemic inflammatory chronic illness. Patients enrolled in the study had no history of a known psychiatric disorder or psychiatric/psychological treatment. Patients who were on psychotropic medication or who received any form of psychotherapy treatment were excluded of the study. None of the patients had a history of psychiatric hospitalization in the past. Baseline demographic data and clinical characteristics of all patients are presented in Table 1. Informed consent was obtained from all patients, as approved by the Human Study Committee of our Institution.

Table 1.

Demographic data and clinical characteristics in all chronic heart failure patients (n = 36)

| Age, yr | 54 ± 12 |

| Gender, (M/F) | 30/6 |

| BMI, kg/m² | 28.3 ± 4.9 |

| NYHA class I/II/III | (10/20/6) |

| LVEF | 33% ± 10% |

| CHF Etiology | |

| Non-ischemic | 18 (50%) |

| Ischemic | 18 (50%) |

| Medical treatment | |

| ACE inhibitors | 88% |

| β-blockers | 85% |

| Diuretics | 85% |

| Spironolactone | 52% |

| Amiodarone | 35% |

| Digitalis | 11% |

| Nitrates | 20% |

| Antiplatelets | 44% |

| Anticoagulants | 23% |

Continuous variables values are presented as means ± SD. BMI: Body mass index; NYHA: New York Heart Association; LVEF: Left ventricle ejection fraction; ACE: Angiotensin-converting enzyme; CHF: Chronic heart failure.

Design of the study

All patients underwent an incremental symptom-limited CPET, and the day of exercise testing they were administered a questionnaire consisted of a self-rating psychometric tests battery to complete in their home. Data collection was obtained from patients’ questionnaire responses and analyzed by an expert clinician to psychiatric disorders.

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

All patients performed a symptom-limited CPET on an electro-magnetically braked cycle ergometer (Ergoline 800; Sensor Medics, Anaheim, California, United States). The work rate increment was estimated by using Hansen et al[26]’s equation in order to attain test duration of 8-12 min. Measurements were recorded for 2 min at rest, for 3 min of unloaded pedaling before exercise, during exercise and for recovering period. Oxygen saturation was measured continuously by pulse oximetry, heart rate and rhythm were monitored by a MAX1, 12-lead ECG System (Marquette), arterial pressure was measured every 2 min with a mercury sphygmomanometer. Oxygen uptake (VO2), carbon dioxide output (VCO2) and ventilation (VE) were measured breath-by-breath. All patients were verbally encouraged to exercise to exhaustion, as defined by intolerable leg fatigue or dyspnea.

Cardiopulmonary measurements

The gas exchange measurements served to calculate VO2 at peak exercise (VO2 peak, mL/kg per minute), anaerobic threshold (AT, mL/kg per minute), and VE/VCO2 slope between exercise onset and AT. The peak values for VO2, VCO2, and VE were calculated as the average of measurements made during the 20-s period before exercise was terminated. AT was determined using the V-slope technique[27], and the result was confirmed graphically from a plot of ventilatory equivalent for oxygen (VE/VO2) and carbon dioxide (VE/VCO2) against time. The ventilatory response to exercise was calculated as the slope by linear regression of VE vs VCO2 from the beginning of exercise to AT, where the relationship is linear, calculated as in previous study[28].

Personality measurements

Personality traits were assessed with the widely used NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI, Greek version), which is a 60-item self-report questionnaire based on the five factor model of personality. The NEO-FFI[29] is a shortened version of the NEO-PI-R (Costa and McCrae 1992). Patients rate each item on a five-point Likert-like scale. Each item-score ranges on a scale from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (4). The instrument is designed to measure each of the well-established five factors of personality: Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness. The Five Factor Model of personality[29,30] is a personality concept that includes behavioral, emotional as well as cognitive personality patterns.

Neuroticism reflects distress-proneness, negative emotions and chronic emotional maladjustment, stress reactivity and instability. Extraversion refers to positive mood, sociability, need for stimulation, vigor, quantity and intensity of preferred interpersonal interactions as well as activity level and capacity for enjoyment. Openness refers to openness to experience as well as active seeking and appreciation of experiences for their own sake, and also involves entailing interest in novel ideas, aesthetic and intellectual sensibility. Agreeableness is an interpersonal factor reflecting altruism, trust, amicability, and also refers to the kind of interactions a person prefers along a continuum from compassion to antagonism. Conscientiousness involves organization, persistence, control, reliability, diligence, and also assesses the degree of achievement-orientated behavior and motivation in goal-directed behavior.

Quality of life measurements

As a measurement of QoL in CHF patients the Greek version of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire was used. The KCCQ is a 23-item, disease specific questionnaire that quantifies the domains of health status that are symptoms (frequency, severity, change over time), physical limitations, a heart failure specific assessment of their quality of life and self-efficacy domain that is a measure of patients’ knowledge of how to best manage their disease. The psychometric properties of the KCCQ have been well documented[3].

The use of the KCCQ in outpatient clinical practice can both quantify patients’ health status and provide insight into their prognosis[8]. QoL identifies CHF patients at risk for hospitalization or death, as a low KCCQ score is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in patients with CHF[7]. Studies have been shown that cross-sectional variations[7,8] as well as changes in serial health status assessments[9] in KCCQ scores are prognostic indicators of subsequent mortality as well as hospitalizations due to CHF.

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD. A P value of 0.05 or lower was considered as statistically significant. All variables were tested for normal distribution. Pearson’s coefficient was used to assess correlations between the study variables. A multivariate linear regression analysis using simultaneous entry of predictors was performed to examine which variables were correlated independently to QoL scores in the two summary scales of the KCCQ that are the overall summary scale (OSS) and the clinical summary scale (CSS). The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Statistics 17.0) software was used to analyze the data.

RESULTS

Psychometric and cardiopulmonary exercise testing measurements are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Psychometric and cardiopulmonary exercise testing measurements in all chronic heart failure patients (n = 36)

| KPLS | 85 ± 14 |

| KSSS | 64 ± 21 |

| KSFS | 86 ± 16 |

| KSBS | 80 ± 19 |

| KTSS | 82 ± 17 |

| KSES | 67 ± 27 |

| KQOLS | 57 ± 24 |

| KSLS | 75 ± 26 |

| KOSS | 75 ± 17 |

| KCSS | 85 ± 14 |

| Neuroticism | 16 ± 5 |

| Extraversion | 29 ± 8 |

| Openness | 25 ± 5 |

| Agreeableness | 26 ± 6 |

| Conscientiousness | 30 ± 5 |

| VO2 peak, mL/kg per minute | 15.9 ± 4.4 |

| WRp, Watt | 99 ± 41 |

| VE/VCO2 slope | 35 ± 7 |

| AT, mL/kg per minute | 9.7 ± 2.4 |

KCCQ: Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; KPLS: Kansas Physical Limitation Score; KSSS: Kansas Symptom Stability Score; KSFS: Kansas Symptom Frequency Score; KSBS: Kansas Symptom Burden Score; KTSS: Kansas Total Symptom Score; KSES: Kansas Self-Efficacy Score; KQOLS: Kansas Quality of Life Score; KSLS: Kansas Social Limitation Score; KOSS: Kansas Overall Summary Score; KCSS: Kansas Clinical Summary Score; VO2 peak: Peak oxygen uptake; WRp: Peak work rate; VE/VCO2 slope: The slope of ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide output during exercise; AT: Anaerobic threshold.

Correlation analysis

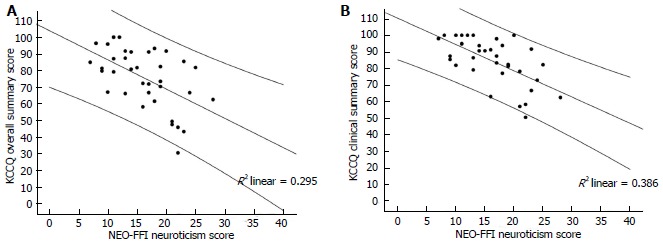

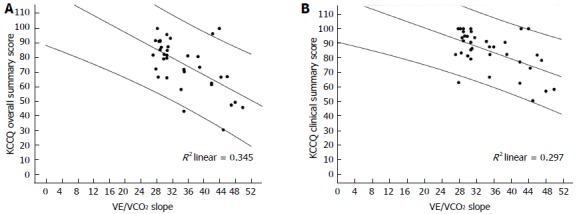

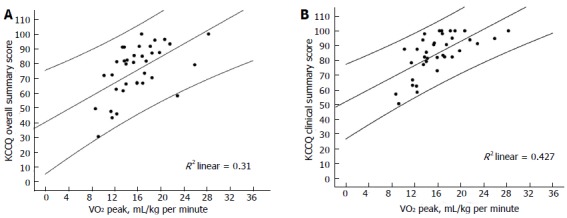

The correlations between KCCQ QoL measurements and NEO-FFI personality parameters, by means of Pearson’s coefficients showed a strong relationship between QoL and Neuroticism (Table 3 and Figure 1). KCCQ summary scales did not show significant correlations with the personality traits of Extraversion, Openness, Conscientiousness and Agreeableness (Table 3). QoL as measured by the OSS and CSS subscales of the KCCQ, had also a significant correlation with CHF severity (Figures 2 and 3) as expressed by VE/VCO2 slope (r = -0.59, P < 0.001 and r = -0.55, P < 0.001, respectively) and VO2 peak (r = 0.56, P < 0.001 and r = 0.65, P < 0.001, respectively).

Table 3.

Pearson’s Simple Correlations between Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Quality of Life and NEO Five-Factor Inventory personality parameters

| KPLS | -0.53b | -0.01 | 0.31 | -0.15 | -0.03 |

| KSSS | -0.30 | -0.02 | -0.06 | -0.17 | -0.15 |

| KSFS | -0.54b | -0.31 | -0.09 | -0.41 | -0.24 |

| KSBS | -0.57b | -0.27 | -0.15 | -0.27 | -0.37 |

| KTSS | -0.61b | -0.29 | -0.09 | -0.35 | -0.32 |

| KSES | 0.00 | -0.14 | -0.24 | -0.28 | -0.42 |

| KQOLS | -0.38a | -0.13 | -0.02 | -0.26 | -0.31 |

| KSLS | -0.39a | -0.12 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| KOSS | -0.54b | 0.05 | 0.08 | -0.19 | -0.07 |

| KCSS | -0.62b | -0.08 | 0.10 | -0.28 | -0.10 |

| Neuroticism | Extraversion | Openness | Agreea- bleness | Conscien- tiousness |

The statistical significance was set at P value < 0.05.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01. KCCQ: Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; KPLS: Kansas Physical Limitation Score; KSSS: Kansas Symptom Stability Score; KSFS: Kansas Symptom Frequency Score; KSBS: Kansas Symptom Burden Score; KTSS: Kansas Total Symptom Score; KSES: Kansas Self-Efficacy Score; KQOLS: Kansas Quality of Life Score; KSLS: Kansas Social Limitation Score; KOSS: Kansas Overall Summary Score; KCSS: Kansas Clinical Summary Score; NEO-FFI: NEO Five-Factor Inventory.

Figure 1.

Scattergrams of correlation of Quality of Life subscales (Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Overall Summary Score, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Clinical Summary Score) with NEO- Five-Factor Inventory Neuroticism personality trait (A and B, respectively).

Figure 2.

Scattergrams of correlations of Quality of Life (Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Overall Summary Score, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Clinical Summary Score) with VE/VCO2 slope (A and B, respectively).

Figure 3.

Scattergrams of correlation of Quality of Life (Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Overall Summary Score, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Clinical Summary Score) with VO2 peak (A and B, respectively).

Model of predictors of Quality of life

A univariate linear regression was performed to examine which variables were significantly correlated to QoL scales, including age, Body Mass Index, Personality traits, VE/VCO2 slope and VO2 peak.

Multivariate linear regression analysis using simultaneous entry of predictors was conducted to determine the best linear combination of statistically significant univariate predictors such as Neuroticism, VE/VCO2 slope and VO2 peak, for predicting KCCQ Overall Summary Score. The results show that Neuroticism (β = 0.32, P < 0.05), VE/VCO2 slope (β = 0.41, P < 0.05) are independent predictors of QoL (adjusted R2 = 0.51, F = 13.33, P < 0.001), with VO2 peak showing a trend (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multiple linear regression analyses of predictors of Quality of Life

| Variables | KCCQ summary scales | |||||||

|

KCCQ Overall Summary Score adjusted R2 = 0.51; F = 13.33,

P < 0.001 |

KCCQ Clinical Summary Score adjusted R2 = 0.64; F =18.89,

P < 0.001 |

|||||||

| B | SE | beta | Sig. | B | SE | beta | Sig. | |

| Neuroticism | -1.02 | 0.43 | -0.32 | P < 0.05 | -0.95 | 0.31 | -0.37 | P < 0.05 |

| VE/VCO2 slope | -1.01 | 0.32 | -0.41 | P < 0.05 | -0.6 | 0.23 | -0.31 | P < 0.05 |

| VO2 peak | 1.04 | 0.55 | 0.26 | NS | 1.16 | 0.39 | 0.37 | P < 0.05 |

KCCQ: Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; VE/VCO2 slope: The slope of ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide output during exercise; VO2 peak: Peak oxygen uptake.

Multivariate linear regression analysis using simultaneous entry of predictors was also conducted to determine the best linear combination of statistically significant univariate predictors such as Neuroticism, VE/VCO2 slope and VO2 peak, for predicting KCCQ Clinical Summary Score. The results show Neuroticism (β = -0.37, P < 0.05), VE/VCO2 slope (β = -0.31, P < 0.05) and VO2 peak (β = 0.37, P < 0.05) to be independent predictors of QoL (Table 4). Even after accounting for CHF etiology, no changes emerged concerning the predictors in the two models described above.

DISCUSSION

This study provides confirming evidence for the hypothesis that personality factors affect QoL in CHF. More specifically, in our study the personality trait of Neuroticism is associated with QoL independently of the CHF severity. To our knowledge this study is the first to show that the personality trait of Neuroticism, estimated by the NEO-FFI, affects QoL, in CHF patients after adjustment for disease severity evaluated by a symptom-limited cardiopulmonary exercise test.

Previous researchers have reported that Neuroticism, estimated by the Eysenk Personality Inventory, can predict the mental health component of the generic QoL, after adjustment for disease severity (assessed by the 6-min walk distance)[22]. A positive correlation between Neuroticism and depression was also found by the same research group in CHF patients[24]. In a prospective cohort study, Murberg et al[23] using the Eysenk Personality Questionnaire have shown that Neuroticism, predicts mortality in CHF independently of the disease severity (assessed by the pro-ANP biochemical prognostic marker). In our study, the Neuroticism trait emerged as an independent predictor of QoL in CHF patients, even after adjustment for the most robust prognostic indicators of mortality, namely cardiopulmonary exercise, stress test parameters, confirming previous reports. Furthermore, CHF patients enrolled at the present study were receiving modern optimal medical treatment including beta-blockers, ACE-inhibitors, aldosterone antagonists.

Recently, other studies have examined the relationship between personality and QoL and demonstrated that type D personality is independently associated with impaired health status in CHF[14,31]. Previous data have also supported the finding that the relationship between personality type-D and CHF is not confounded by disease severity, assessed by BNP measurements[32]. In the present study we have shown that the personality trait of Neuroticism, affects independently QoL in CHF patients. The relationship between type-D personality and Neuroticism has been previously studied and a positive relationship was found between them in both subscales of the type-D evaluation tool DS14, namely the Negative Affectivity and Social Inhibition[33]. Other psychological factors such as depression and anxiety have also been associated with decreased QoL in CHF patients[12].

Our data have shown that CHF patients who score high on the Neuroticism scale have low QoL independently of the severity of the CHF as expressed by VE/VCO2 slope and VO2 peak, strong predictors of mortality[28]. Because of the cross-sectional design of the study, the results are by definition bidirectional. Nevertheless it could plausibly be assumed that the direction of the relationship is rather from Neuroticism to impaired QoL, as personality traits are usually formed before the age of 30 and tend to remain stable through the rest of adulthood[34-37]. As supported by epidemiological data, CHF usually occurs mainly after the age of 30, increasing incidence with aging[38,39]. Thus it can be inferred that the development of Neuroticism personality trait precedes the development and progress of CHF.

Chronic stress pattern and autonomic dysregulation might explain the relationship between Neuroticism and QoL found in our data. The personality trait of Neuroticism is correlated to chronic anxiety[40]. Neuroticism leads to a dysfunctional pattern of stress management as well as a pattern of frequent experience of negative feelings in everyday life, and that means vulnerability to common psychological stressors. This chronic inadequate stress management predisposes to autonomic nervous dysfunction[41] and cardiovascular dysregulation[42,43]. The relationship between chronic stress and cardiovascular dysfunction is also well known in animals[44]. A recent study has shown that type-D personality is correlated to impaired heart rate recovery[45], an index of parasympathetic abnormality. This index is related to psychological distress and QoL and is a strong independent predictor of mortality[46] and poor QoL[47] in CHF patients. It could be assumed that this autonomic nervous system dysregulation is a possible mechanism that might mediate the relationship between Neuroticism and decreased health status in CHF patients. Future studies are needed to evaluate the possible association of Neuroticism with autonomic nervous system impairment in CHF patients.

Our study supports the hypothesis that a more holistic approach is preferable, when evaluating a patient with chronic heart failure, a finding of significant clinical importance. A low KCCQ score is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in outpatients with CHF[7-9] and according to the findings of present study, this is not only related to disease severity but also predicted by a high NEO-FFI Neuroticism score. Patients scoring high in the Neuroticism personality trait have lower QoL independently of CHF severity, therefore, Neuroticism may constitute a prognostic factor for these patients. The knowledge of the severity of the Neuroticism trait could also affect the treatment options, as it can help with the identification of patients that probably need additional psychological or psychiatric care to cope with their heart disease.

Certain limitations of the study should be taken into account during result interpretation. This study is cross-sectional, therefore not designed to prove causality. Intervention studies targeting Neuroticism with prospective design are needed for clarifying the direction of the relationships between Neuroticism, CHF severity and QoL, in terms of their predictive value for clinical outcome. No structured clinical interview was used as a screening tool for psychopathology in this non-psychiatric setting sample of ambulatory patients of the outpatient Heart Failure Clinic. Due to the small number of female patients in our sample, it was not possible to perform gender-specific analysis and/or between-gender comparisons. Duration of disease variables was not included in the analysis, but disease severity estimation was based only on current measurements via the CPET and the psychometric evaluation. Although duration of diagnosis it is not theoretically possible to affect personality traits of the patients, it might affect QoL. Due to the small sample size it was not possible to control for anxiety and depression levels. Larger sample size and sophisticated statistical methods could help to further highlight the association between Neuroticism, CHF severity and QoL. A prospective study of exercise rehabilitation program effects could lead to better exploration of the role of Neuroticism to QoL and disease severity. The role of Neuroticism in other chronic illnesses beyond CHF should be also investigated in future studies.

In conclusion, Neuroticism personality trait predicts independently QoL in CHF patients after adjustment for CHF severity. Notwithstanding the limitations of a small study, we propose that a more flexible approach to CHF diagnosis, which includes personality dimensions along with a description of CHF symptoms, may result in a more inclusive and useful diagnostic scheme for treating people with chronic heart failure. Taking into account the relationship between Neuroticism and QoL, personality factors could probably help to explain at least partially some of the mortality risk in CHF patients previously predicted by poor QoL. Psychiatric interventions might possibly be incorporated into the treatment of these patients to improve QoL and possibly prognosis.

COMMENTS

Background

Measuring and exploring factors that affect Quality of life (QoL) is important for chronic heart failure (CHF) patients in order to monitor their treatment course and assessing prognosis, as well as for evaluating treatment interventions’ and health services effectiveness. Patients that are experiencing low QoL present higher morbidity, hospitalization rate and mortality. QoL in CHF is related to exercise capacity and adherence to rehabilitation programs and low QoL is related to exercise training intolerance. Of the psychological factors that affect QoL, anxiety and depression levels have been shown to play an important role, but the role of personality traits of the CHF patient hasn’t been well understood yet. Taking into account that the personality trait of Neuroticism, has been demonstrated to affect QoL in chronically ill individuals, there is a need for exploration of its possible role as a predictor of QoL in patients with CHF.

Research frontiers

Of the available generic and disease-specific tools for describing dimensions of QoL in CHF, the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire is a self-reported, disease specific questionnaire that is considered reliable and valid for this population. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing has emerged over the years as a very useful modality for assessing variables related to exercise capacity and with CHF severity in this population.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Previous researchers have reported that Neuroticism, estimated by the Eysenk Personality Inventory (EPI), can predict the mental health component of the generic QoL, after adjustment for disease severity assessed by the 6-min walk distance. Also a prospective cohort study using the Eysenk Personality Questionnaire (EPQ), an expanded version of EPI, has shown that Neuroticism predicts mortality in CHF independently of the disease severity assessed by the pro-ANP biochemical prognostic marker. These study provides additional evidence for the hypothesis that personality factors affect QoL in CHF. More specifically, these found that the personality trait of Neuroticism is associated with QoL independently of the CHF severity. To these knowledge this study is the first to show that the personality trait of Neuroticism, estimated by the Five-Factor Personality Inventory, affects QoL, in CHF patients after adjustment for disease severity evaluated by a symptom-limited cardiopulmonary exercise test, the “gold” standard for the assessment of exercise capacity in these patients.

Applications

The results of this study showed that not only disease severity but also the personality characteristic of Neuroticism can affect patients’ QoL, therefore worsening prognosis of CHF. The personality of CHF patient has to be taken into account during CHF treatment and rehabilitation programs, and a tailor-made individualized psychosocial intervention by a mental health professional might help improving patients QoL and consequently CHF prognosis.

Terminology

CHF population in this manuscript refers to patients with Chronic Heart Failure, that are currently been stabilized in optimal medical treatment and their left ventricle ejection fraction remains less than 45%. CPET refers to CardioPulmonary Exercise Testing that is used for evaluation of the patient in terms of heart function and exercise capacity. This evaluation is also important for exercise training rehabilitation of the CHF patient.

Peer review

This is a very interesting and novel observational study of the effect of neuroticism on quality of life of a Greek cohort of chronic heart failure patients. The paper reads well overall and reports some novel findings.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Brugts JJ, Lymperopoulos A, Nunez-Gil IJ S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Spertus J. Selecting end points in clinical trials: What evidence do we really need to evaluate a new treatment? Am Heart J. 2001;142:745–747. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.119135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Normand SL, Rector TS, Neaton JD, Piña IL, Lazar RM, Proestel SE, Fleischer DJ, Cohn JN, Spertus JA. Clinical and analytical considerations in the study of health status in device trials for heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005;11:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juenger J, Schellberg D, Kraemer S, Haunstetter A, Zugck C, Herzog W, Haass M. Health related quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure: comparison with other chronic diseases and relation to functional variables. Heart. 2002;87:235–241. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Athanasopoulos LV, Dritsas A, Doll HA, Cokkinos DV. Comparative value of NYHA functional class and quality-of-life questionnaire scores in assessing heart failure. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2010;30:101–105. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181be7e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Athanasopoulos LV, Dritsas A, Doll HA, Cokkinos DV. Explanation of the variance in quality of life and activity capacity of patients with heart failure by laboratory data. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:375–379. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328333e962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heidenreich PA, Spertus JA, Jones PG, Weintraub WS, Rumsfeld JS, Rathore SS, Peterson ED, Masoudi FA, Krumholz HM, Havranek EP, et al. Health status identifies heart failure outpatients at risk for hospitalization or death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:752–756. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soto GE, Jones P, Weintraub WS, Krumholz HM, Spertus JA. Prognostic value of health status in patients with heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;110:546–551. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136991.85540.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kosiborod M, Soto GE, Jones PG, Krumholz HM, Weintraub WS, Deedwania P, Spertus JA. Identifying heart failure patients at high risk for near-term cardiovascular events with serial health status assessments. Circulation. 2007;115:1975–1981. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.670901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flynn KE, Piña IL, Whellan DJ, Lin L, Blumenthal JA, Ellis SJ, Fine LJ, Howlett JG, Keteyian SJ, Kitzman DW, et al. Effects of exercise training on health status in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1451–1459. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, Keteyian SJ, Cooper LS, Ellis SJ, Leifer ES, Kraus WE, Kitzman DW, Blumenthal JA, et al. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1439–1450. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung ML, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Rayens MK. The effects of depressive symptoms and anxiety on quality of life in patients with heart failure and their spouses: testing dyadic dynamics using Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faller H, Steinbüchel T, Störk S, Schowalter M, Ertl G, Angermann CE. Impact of depression on quality of life assessment in heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2010;142:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.12.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiffer AA, Pedersen SS, Widdershoven JW, Hendriks EH, Winter JB, Denollet J. The distressed (type D) personality is independently associated with impaired health status and increased depressive symptoms in chronic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005;12:341–346. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000173107.76109.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spindler H, Kruse C, Zwisler AD, Pedersen SS. Increased anxiety and depression in Danish cardiac patients with a type D personality: cross-validation of the Type D Scale (DS14) Int J Behav Med. 2009;16:98–107. doi: 10.1007/s12529-009-9037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiffer AA, Smith OR, Pedersen SS, Widdershoven JW, Denollet J. Type D personality and cardiac mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2010;142:230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.12.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jerant A, Chapman BP, Franks P. Personality and EQ-5D scores among individuals with chronic conditions. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:1195–1204. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9401-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapman BP, Duberstein PR, Sörensen S, Lyness JM. Personality and perceived health in older adults: the five factor model in primary care. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61:P362–P365. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.6.p362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duberstein PR, Sörensen S, Lyness JM, King DA, Conwell Y, Seidlitz L, Caine ED. Personality is associated with perceived health and functional status in older primary care patients. Psychol Aging. 2003;18:25–37. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilhooly M, Hanlon P, Cullen B, Macdonald S, Whyte B. Successful ageing in an area of deprivation: part 2--a quantitative exploration of the role of personality and beliefs in good health in old age. Public Health. 2007;121:814–821. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodwin R, Engstrom G. Personality and the perception of health in the general population. Psychol Med. 2002;32:325–332. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701005104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westlake C, Dracup K, Creaser J, Livingston N, Heywood JT, Huiskes BL, Fonarow G, Hamilton M. Correlates of health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2002;31:85–93. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2002.122839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murberg TA, Bru E, Svebak S, Tveterås R, Aarsland T. Depressed mood and subjective health symptoms as predictors of mortality in patients with congestive heart failure: a two-years follow-up study. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1999;29:311–326. doi: 10.2190/0C1C-A63U-V5XQ-1DAL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Westlake C, Dracup K, Fonarow G, Hamilton M. Depression in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005;11:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Thoracic Society; American College of Chest Physicians. ATS/ACCP Statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:211–277. doi: 10.1164/rccm.167.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansen JE, Sue DY, Wasserman K. Predicted values for clinical exercise testing. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;129:S49–S55. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.129.2P2.S49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beaver WL, Wasserman K, Whipp BJ. A new method for detecting anaerobic threshold by gas exchange. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1986;60:2020–2027. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.6.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nanas SN, Nanas JN, Sakellariou DCh, Dimopoulos SK, Drakos SG, Kapsimalakou SG, Mpatziou CA, Papazachou OG, Dalianis AS, Anastasiou-Nana MI, et al. VE/VCO2 slope is associated with abnormal resting haemodynamics and is a predictor of long-term survival in chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costa PT, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Digman J. Personality Structure: Emergence of the 5-Factor Model. Annu Rev Psychol. 1990:417–440. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedersen SS, Herrmann-Lingen C, de Jonge P, Scherer M. Type D personality is a predictor of poor emotional quality of life in primary care heart failure patients independent of depressive symptoms and New York Heart Association functional class. J Behav Med. 2010;33:72–80. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9236-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pelle AJ, van den Broek KC, Szabó B, Kupper N. The relationship between type D personality and chronic heart failure is not confounded by disease severity as assessed by BNP. Int J Cardiol. 2010;145:82–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Fruyt FDJ. Type D personality: A Five-Factor Model perspective. Psychol Health. 2002;17:671–683. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costa PT, McCrae RR. Personality in adulthood: a six-year longitudinal study of self-reports and spouse ratings on the NEO Personality Inventory. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:853–863. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.5.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terracciano A, Costa PT, McCrae RR. Personality plasticity after age 30. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2006;32:999–1009. doi: 10.1177/0146167206288599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCrae RR, Costa PT, Arenberg D. Constancy of adult personality structure in males: longitudinal, cross-sectional and times-of-measurement analyses. J Gerontol. 1980;35:877–883. doi: 10.1093/geronj/35.6.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costa PT, McCrae RR, Zonderman AB, Barbano HE, Lebowitz B, Larson DM. Cross-sectional studies of personality in a national sample: 2. Stability in neuroticism, extraversion, and openness. Psychol Aging. 1986;1:144–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cowie MR, Mosterd A, Wood DA, Deckers JW, Poole-Wilson PA, Sutton GC, Grobbee DE. The epidemiology of heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:208–225. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cowie MR, Wood DA, Coats AJ, Thompson SG, Poole-Wilson PA, Suresh V, Sutton GC. Incidence and aetiology of heart failure; a population-based study. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:421–428. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brandes M, Bienvenu OJ. Personality and anxiety disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8:263–269. doi: 10.1007/s11920-006-0061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watkins LL, Blumenthal JA, Carney RM. Association of anxiety with reduced baroreflex cardiac control in patients after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2002;143:460–466. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.120404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grippo AJ, Johnson AK. Stress, depression and cardiovascular dysregulation: a review of neurobiological mechanisms and the integration of research from preclinical disease models. Stress. 2009;12:1–21. doi: 10.1080/10253890802046281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lucini D, Di Fede G, Parati G, Pagani M. Impact of chronic psychosocial stress on autonomic cardiovascular regulation in otherwise healthy subjects. Hypertension. 2005;46:1201–1206. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000185147.32385.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sgoifo A, Pozzato C, Costoli T, Manghi M, Stilli D, Ferrari PF, Ceresini G, Musso E. Cardiac autonomic responses to intermittent social conflict in rats. Physiol Behav. 2001;73:343–349. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00455-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Känel R, Barth J, Kohls S, Saner H, Znoj H, Saner G, Schmid JP. Heart rate recovery after exercise in chronic heart failure: role of vital exhaustion and type D personality. J Cardiol. 2009;53:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nanas S, Anastasiou-Nana M, Dimopoulos S, Sakellariou D, Alexopoulos G, Kapsimalakou S, Papazoglou P, Tsolakis E, Papazachou O, Roussos C, et al. Early heart rate recovery after exercise predicts mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2006;110:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Känel R, Saner H, Kohls S, Barth J, Znoj H, Saner G, Schmid JP. Relation of heart rate recovery to psychological distress and quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16:645–650. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283299542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]