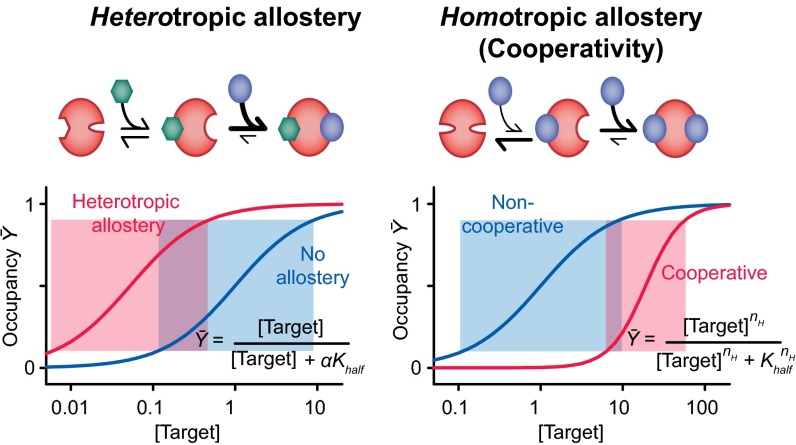

Fig. 1.

Nature often controls the shape and position of ligand–response curves via allostery. (Left) In heterotropic allostery, the binding of one ligand to a receptor increases or decreases the affinity with which a second, different ligand binds, shifting the placement of the binding curve without altering its shape and thus without altering the width of its useful dynamic range (shaded boxes) or, in turn, its sensitivity to small changes in target concentration. (Right) In homotropic allostery, in contrast, the binding of one copy of target ligand changes the affinity with which additional copies of the same ligand bind, altering both the placement and the shape of the binding curve. The latter effect allows the system to respond more (positive cooperativity) or less (negative cooperativity) sensitively to changes in target ligand concentration. For positive cooperativity, receptor occupancy is a higher (than unity) order function of target concentration, with the exponent, nH, being known as the Hill coefficient.