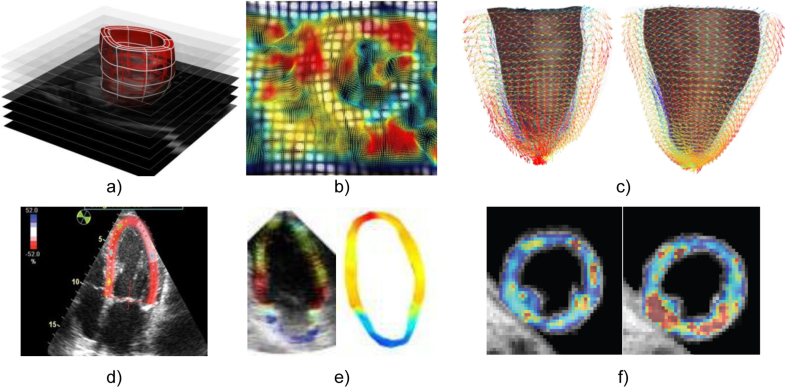

Fig. 4.

Illustration of techniques used to capture the mechanical information available in images. (a) Computational mesh of the left ventricle fitted to the domain of the myocardium from the end-diastolic frame of a MRI dynamic short axis stack (Lamata et al., 2011). (b) Tagged MRI frame of a short axis view of the left ventricle with an overlay of a colour encoded deformation field estimated from it by image registration (Chandrashekara et al., 2004). (c) Computational mesh fitted to in vivo DT-MRI data (Toussaint et al., 2013) at two instants of the cardiac cycle, systole (left) and diastole (right), with vectors pointing in the direction of the first eigenvector (fibre), colour encoded with respect to the elevation angle (red to blue, +45 to −45). (d) Echocardiographic speckle tracking (Ledesma-Carbayo et al., 2005). (e) Echocardiography-based electromechanical wave imaging (EWI), illustrating the motion maps (left) and the EWI isochrones (right; both colour coded from 0 ms, red, to 300 ms, blue; Provost et al., 2011b). (f) Elastography by the methods described in (Robert et al., 2009): the panel illustrates the shear modulus in a healthy volunteer at two time points of the cardiac cycle (image courtesy of Dr. R. Sinkus, KCL).