Abstract

Objectives

Latinos are the fastest-growing immigrant group in the USA. Yet, little is known about the emotional well-being of this population, such as the links among family, neighbourhood context and Latino immigrant youth mental health. Understanding this link will help determine which contexts negatively impact Latino immigrant youth mental health.

Design

Drawing data from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighbourhoods collected in 1994–1995 and 1997–1999, this study examined links between Latino youth’s internalising behaviours, based on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), and neighbourhood characteristics as a function of immigrant status. The sample included 1040 (aged 9–17) Latino immigrant youth seen twice over three years and identified as first, second or third generation. In this study, neighbourhoods are made up of two to three census tracts that reflect similar racial/ethnic and socioeconomic composition. Using hierarchical linear regression models, the study also explored links between internalising behaviours and neighbourhood characteristics, including concentrated disadvantage, immigrant concentration and residential stability.

Results

First- and second-generation youth had higher internalising behaviour scores (i.e., worse mental health) than third-generation youth after controlling for youth internalising behaviours at Wave 1, maternal depression and family characteristics. First- and second-generation youth were more likely to live in high immigrant-concentrated neighbourhoods and first-generation youth were more likely to live in residentially unstable neighbourhoods. Controlling for neighbourhood clusters eliminated the immigrant-generation internalising association. However, second-generation Latino youth living in neighbourhoods with higher residential stability had higher levels of internalising behaviour problems compared to first- and third-generation youth living in similar neighbourhoods.

Conclusions

We found that the interaction between immigrant generation and neighbourhood context helps to explain differences observed in the mental health of second-generation immigrant youth, a result that may help other communities in the USA and other countries better understand the factors that contribute to immigrant youth well-being.

Keywords: Latinos, immigrant youth, internalising behaviours, neighbourhoods

Immigration brings about change for the immigrants as well as their families (e.g., children). In the USA, children of immigrants are among the fastest-growing segments of the population (Hernandez 2004). Based on 2000 US Census data, Hernandez (2004) estimated that Latino children of immigrants make up 62% of all children of immigrants. It is expected that by the year 2020, Latino children of immigrants will comprise 30% of the nation’s children, making Latinos the largest group among immigrant families (Infoplease 2009). Given the rapid growth in the number of Latino children, it is important to understand the mental health of this population. Social science research has largely focused on immigrant adults; much less is known about the mental health of youth born to immigrant parents or immigrant youth themselves (Harris 1999, Kao 1999, Harker 2001, Portes and Rumbaut 2001). One measure of mental health status includes an assessment of depressive and anxious behaviours (i.e., internalising behaviours). High levels of internalising behaviours have been linked to poor outcomes such as mental health problems and substance abuse (Ollendick and King 1994, King et al. 2004). Given the importance of examining factors associated with youth mental health, it is vital that we explore the links that are relative to Latino immigrant youth, a severely understudied population.

A few studies have examined symptoms of depression and anxiety among Latinos (Loukas and Prelow 2004, Smokowski and Bacallao 2007, Varela et al. 2007). However, these studies grouped immigrant groups together and overlooked the role played by immigrant generation in the link between generation and depressive or internalising behaviours. Differential experiences may result from belonging to a given immigrant generation. For example, immigrant families whose parents are foreign-born and children are born in the USA (i.e., second-generation children) are considered mixed-status families (Fix and Zimmermann 1999) and face differential access to benefits (e.g., health care). To differentiate between immigrant generations, social scientists (Sampson et al. 2005, Leventhal et al. 2006) have defined three generations: first generation (both parents are foreign-born and child is foreign-born), second generation (at least one foreign-born parent and US-born child) and third generation (both parents and child are US-born). Yet these groupings are rarely applied. In addition to overlooking immigrant generation and its link to youth mental health, the role that neighbourhood context plays in immigrant youth mental health has yet to be examined empirically. This latter point is important, given that Latino immigrant families are more likely than whites to live in poor and marginalised neighbourhoods (Sampson and Sharkey 2008).

The following literature review focuses on the two primary issues under consideration in the study: immigrant youth well-being and links between neighbourhood context and youth well-being.

Immigrant generation and well-being

Few studies (Glover et al. 1999) have examined links between immigrant generation and child mental health outcomes. Their results have been equivocal. Harris (1999), who studied more than 20,000 youth in grades 7 through 12, and Harker (2001), whose sample included 13,350 seventh- through twelfth-graders, found that first-generation youth exhibited lower levels of depression than their second- and third-plus-generation immigrant counterparts. In her sample of 24,559 eighth-graders, Kao (1999) found lower levels of self-efficacy and a lesser sense of control among first-and second-generation Latino immigrants relative to third-generation immigrants. In a sample of 2200 twelve- to seventeen-year-olds, Roberts and Sobhan (1992) found that Mexican youths, particularly girls, reported higher levels of depression compared to Black and White adolescents. Others (Spencer and Markstrom-Adams 1990, Garcia-Coll et al. 1996, Cuellar and Roberts 1997) have delved more deeply into the factors associated with immigrant mental health, such as socioeconomic status (SES) and race/ethnicity, to provide more critical analyses of the processes associated with immigration youth mental health.

Recent studies (Yu et al. 2003, Xue et al. 2005) have pointed to a variety of risk factors that might be associated with internalising behaviours during adolescence, including SES, parental depression and neighbourhood residence. For example, numerous studies (Duncan et al. 1994, Lipman and Offord 1997) examining the associations between family SES and children’s mental health outcomes have indicated that low SES is associated with more depressive behaviours in children. Some scholars (Aber et al. 1997) have contended that the effects of poverty are direct, impacting the child’s access to good nutrition, housing and other basic necessities. Other researchers (Guo and Harris 2000) have argued that the negative effects of poverty are indirect, acting primarily to decrease parents’ mental health and impoverish home environments. Furthermore, numerous studies (Biederman et al. 2001) have shown a link between maternal depression and anxiety and internalising behaviours among youth. Other studies (Brooks-Gunn and Duncan 1997, Beiser et al. 2002, Pachter et al. 2006) have shown a link between high rates of depression among poor mothers and higher rates of child and adolescent internalising behaviours, which is also evident in minority and immigrant populations.

How these factors are specifically associated with internalising behaviours and Latino youth is not known. Parents of first-generation Latino youth are less educated, poorer and less likely to be English-proficient (Capps et al. 2004, Cabrera et al. 2006). However, such families are more likely to have two parents in the home and strong parental support (Formoso et al. 2000, Shields and Behrman 2004). While immigrant families are more likely to be poor, they appear to be better off than White families in terms of family disruption and negative neighbourhood influences. According to Capps et al. (2004), children of immigrants are much more likely to live in two-parent homes compared to ‘natives.’ Shields and Behrmann (2004) found that only 16% of youth born to immigrants live in single-parent families (relative to 26% of youth born to native parents), and even in these single-parent families, youth of immigrants are more likely to be surrounded by a large extended family and large social networks within the community. These intact families and strong community bonds may help to reduce the effects of poverty on child internalising behaviours in immigrant populations. Furthermore, children living in two-parent families exhibit better mental health outcomes compared to children in single-parent households (McLanahan and Sandfur 1994, Waldfogel et al. 2010). Still, parent marital status does not completely protect children, especially immigrant children who are significantly more likely to live in poverty despite living with two parents. Two-parent immigrant families are much less likely to have both parents working, and when they are working, their wages are comparatively low. This wage gap potentially impacts youth’s access to resources (Elmelech et al. 2002, Capps et al. 2004, Cauthen and Dinan 2006).

In addition, immigrant youth may encounter risk factors that extend beyond the home and into the neighbourhood. The following section explores the link between neighbourhood context and youth mental health.

Neighbourhood context and youth mental health

Although links between neighbourhood characteristics and youth mental health have been studied, only a few studies (Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000, Fauth et al. 2007) have examined Latino youth specifically. Among the few that have done so, Aneshensel and Sucoff’s (1996) study of the effects of neighbourhood context on a subsample of Latino youth within a larger, racially/ethnically diverse sample of youth, showed that generally Latino youth living in neighbourhoods with high concentrations of Latinos and low SES exhibited lower levels of depressive behaviours than other Latino youth in the study.

Links have been found between neighbourhood characteristics and youth mental health outcomes (Klebanov et al. 1997, Spencer et al. 1997). For example, residing in a low-SES neighbourhood is associated with higher levels of internalising behaviour (Aneshensel and Sucoff 1996, Chase-Lansdale et al. 1997). Several national and regional studies (Sampson and Groves 1989, Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000) have suggested that residing in low-SES neighbourhoods is associated with increased internalising behaviours, along with higher crime and delinquent behaviour rates. In a randomised trial of moving from public housing in poor neighbourhoods to rental housing in non-poor neighbourhoods, girls in the moving group had lower levels of depressive symptoms compared to girls in the control group (Fauth et al. 2007).

More recently, Xue et al. (2005) found that, in a sample of Latino, African American and non-Latino whites, higher levels of depressive behaviours were present among children aged 5–11 who lived in poor neighbourhoods, even after controlling for family-level characteristics and maternal mental health.

The effects of residential stability on youth outcomes have also been examined (Sampson and Groves 1989, Ennett et al. 1997). However, these studies focused on delinquent behaviours such as substance use and criminal activity. With the exception of the Xue et al. (2005) study, to our knowledge no study has examined links between residential stability and youth depressive behaviours. Residential stability may be more important for youth who were born in the USA compared to first-generation youth who have experienced a major residential relocation, which may mean that residential stability of the receiving neighbourhood is important than for later immigrant generations. Immigrant concentration might be most important for first-generation Latino youth, who may be looking to connect with other immigrants, and less important for later generations (second and third). Given the limited amount of empirical evidence, it is not clear whether neighbourhood poverty, immigrant concentration or residential stability will be linked to internalising behaviour of immigrant youth.

This study aims to address these gaps in the literature by examining links among child, family and neighbourhood characteristics and youth internalising behaviours among a sample of first-, second- and third-generation Latino youth. Using a broad sample of immigrants and controlling for a variety of other factors that have been shown to link with internalising behaviours, this study provides a unique look at factors associated with internalising behaviours among youth who are immigrants or have immigrant parents. This study has three specific goals. The first goal is to determine the extent to which internalising behaviours (e.g., depressive, anxious and withdrawn symptoms) as measured by the Child Behavior Check List (CBCL) are linked with immigrant status among a sample of first-, second- and third-generation Latino youth. The second goal is to determine whether family-level characteristics account for any such generational differences in youth internalising behaviours, controlling for baseline internalising behaviours. The third goal is to determine, by examining links between internalising behaviours and neighbourhood characteristics, whether these links depend on Latino youth immigrant status. The sample comes from the Project on Human Development on Chicago Neighbourhoods and is representative of all Hispanic youth residing in the city of Chicago in the mid-1990s.

Method

Study design

The Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighbourhoods (PHDCN) is a longitudinal study aimed at advancing our understanding of the experiences of children who are growing up in US cities at the turn of this century. The present study uses data from the PHDCN to answer our research questions. Three waves of data on families in 80 neighbourhoods were collected in 1994–1995, 1997–1999 and 2000–2002; this study is based on the first two of these waves. Neighbourhoods were sampled from 343 neighbourhood clusters; these are made up two to three census tracts reflecting similar racial/ethnic and socioeconomic composition and containing approximately 8000 people (Sampson et al. 1997). These neighbourhoods were derived using a two-stage random selection procedure that included neighbourhoods by race and ethnic composition (creating seven categories) and socioeconomic status (low, medium and high). The major geographic boundaries used to construct the neighbourhood clusters included railroad tracks, parks, freeways, etc. In addition, knowledge of Chicago’s local neighbourhoods and cluster analyses of census data guided the construction of neighbourhood clusters so that they were relatively homogeneous with respect to racial/ethnic mix, socioeconomic status, housing density and family structure. Children were selected to participate in the study based on place of residence (i.e., one of the 80 selected neighbourhoods) and age cohort (0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15 and 18) at Wave 1 (similarly to Sampson et al. 1997, Browning et al. 2004). The design of this study makes it possible to explore individual- and neighbourhood-level differences in children’s internalising behaviours, particularly among children of immigrant parents. In the current study we use the first two waves of data. The response rate at Wave 1 was 75%; at Wave 2 the response rate was 86%.

Sample

The present study is based on 1040 Latino youth from three cohorts (9, 12 and 15); mean age was 12. Descriptive statistics for the study sample are shown in Table 1. The Latino sample was 47% of the total sample of youth at these ages. The study focused on three immigrant groups: first generation (24%), second generation (59%) and third generation and beyond (17%).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the overall study sample and by immigrant generation.

| Variable | First generation (n = 250) |

Second generation (n = 611) |

Third generation (n = 179) |

Total (N = 1040) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean internalising score Wave 1 | ||||

| M (SD) | 9.77 (7.31) | 9.42 (7.89) | 7.51 (7.17)* | 9.18 (7.66) |

| Mean internalising score Wave 2 | ||||

| M (SD) | 11.02 (8.73) | 10.16 (8.28) | 8.64 (7.39)* | 10.12 (8.27) |

| Youth characteristics Ethnicity(%) | ||||

| Mexican | 80 | 77 | 70** | 76 |

| Puerto Rican | 12 | 17 | 25 | 17 |

| Other Latino | 8 | 6 | 5 | 7 |

| Age | ||||

| M (SD) | 12.27 (2.41) | 11.82 (2.44) | 11.85 (2.46)* | 11.93 (2.44) |

| Girls (%) | 45 | 50 | 49 | 49 |

| Parent characteristics Needs-to-income ratio | ||||

| M (SD) | 0.95 (0.69) | 1.43 (0.96) | 1.89 (1.28)*** | 1.39(1.01) |

| Education (%) | ||||

| Less than high school | 51 | 40 | 6*** | 37 |

| Some high school | 18 | 19 | 26 | 20 |

| High school graduate | 14 | 16 | 16 | 15 |

| Some post-high school | 13 | 20 | 41 | 22 |

| College or more | 4 | 5 | 11 | 6 |

| Marital status (%) | ||||

| Married | 74 | 67 | 60** | 68 |

| Single | 14 | 20 | 27 | 19 |

| Partnered | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| Maternal depressive Symptoms (%) | 26 | 20 | 20 | 22 |

Note: Reference group for the significant tests were third-generation immigrant youth.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p <0.001.

Measures

Child characteristics

Child characteristics include immigrant generation, gender and age. Child immigration status was determined using mother’s report of the child’s country of origin, her own country of origin and the child’s father’s country of origin, thereby deriving three immigrant generations. Each immigrant generation is defined as follows: first generation includes adolescents born outside of the USA with two parents born outside the USA (24%); second generation refers to US-born adolescents with at least one foreign-born parent (59%); and third generation refers to all US-born adolescents with no foreign-born parent (17%). Two dummy variables were coded to reflect child immigration status (first and second generations), with third-generation youth as the reference group. Age was used as a continuous variable (M=11.93; SD=2.44). Gender was dummy coded (0=male; 1=female).

Parent characteristics

Parent information includes family income-to-needs ratio, maternal education and maternal marital status. Family income-to-needs ratio, a continuous variable, is used as the family income indicator. This ratio is constructed by dividing the reported total annual family income by the official poverty threshold for the respective household size at the time of data collection (i.e., 1995). An income ratio of 1 or <1 indicates poverty (Garcia-Coll et al. 1996). Maternal education was dummy-coded, using mothers with more than a high school education as the reference group. Two dummy variables were coded to indicate marital status (single or partnered), with married as the reference group.

Maternal mental health

PHDCN assessed mothers’ depressive symptoms and major depression using the Comprehensive International Diagnostic Interview short form (CIDI-SF), an international protocol employed by the World Health Organization (Kessler et al. 1998). This instrument screens for a major depressive episode during the 12-month period preceding the interview. The purpose of the screener is to identify individuals who have a high probability of being classified with major depression (Kessler et al. 1998), but does not provide a clinical diagnosis of major depression. The CIDI-SF is a highly valid and reliable diagnostic instrument that has demonstrated 93% classification accuracy for major depressive disorders (Kessler et al. 1998).

Probability scores are based on standard cut points and are dichotomised to indicate whether or not a woman has major depression (e.g., has a probability score of ≥0.55). Neither the severity nor the duration of major depression was assessed in this study. Thirteen per cent of mothers met the depression criteria (a probability score of ≥0.55); they were coded ‘1’ and non-depressed mothers were coded ‘0’. This control variable was necessary because these mothers were reporting on their adolescents’ internalising problems and because a correlation exists between maternal reports of depression and her ratings of her child (Fergusson et al. 1993, Boyle and Pickles 1997). Twenty-two per cent of mothers were classified as depressed. Mothers of first-generation youth had the highest rates of depressive symptoms (26%) compared to mothers of second- and third-generation youth (20% each).

Neighbourhood characteristics

Neighbourhood-level factors include concentrated disadvantage, residential stability and immigrant concentration, as developed by Sampson et al. (1997). Concentrated disadvantage was derived from a factor analysis of the 343 clusters in Chicago. The six items identified were: (1) percentage of households below the poverty line, (2) percentage of residents receiving public assistance, (3) percentage of unemployed residents, (4) percentage of African American residents, (5) percentage of female-headed households and (6) density of children. Immigrant concentration, an additional, oblique factor, reflects neighbourhood differences on race and ethnicity and immigration. This factor is made up of two items: (1) percentage of immigrant residents and (2) percentage of Latino residents. Residential stability includes the percentage of residents living in the same house as five years earlier and the percentage of owner-occupied homes, as per Sampson et al. (1997).

Internalising Behaviours

Internalising behaviours were measured from parent reports using the CBCL (Achenbach 1991), a widely used instrument (Wadsworth et al. 2001, Meurs et al. 2009). The CBCL yields separate scores based on subscales for total problems, internalising problems and externalising problems.

Three subscales from the CBCL were used to assess internalising behaviours: withdrawal, somatic complaints and depressive/anxious behaviours. Parents used a 3-point Likert scale to report how true the statements were of their child during the past six months (0=not true; 1=somewhat true; 2=very true). The Withdrawn subscale includes such questions as ‘How true is it that the child would rather be alone?” The Somatic Complaints subscale assesses the child’s physical well-being, for example whether or not the child experienced dizziness or nausea during the past six months. The third subscale, which assesses depressive/anxious behaviours, is composed of questions about the child’s feeling state. For example, parents were asked if their child felt unloved or worthless during the past six months. In this research, raw scores were used for analyses as per Meurs et al. (2009). Scores from the three subscales were summed to produce a total internalising score for Wave 1 (M=9.18, SD=7.66) and Wave 2 (M=10.12, SD=8.27). Higher scores indicate more internalising problems.

Analytic strategy

Analyses of variance and chi-square tests were completed as a preliminary step to the documentation and comparison of similarities in study variables across immigrant generations. Given the interest in neighbourhood context, the researcher then formulated two-level hierarchical linear models in which youth were nested within neighbourhoods, using HLM software (Raudenbush et al. 2001). Thus, the analysis was proceeded in steps. First, the proportion of variance in mean internalising behaviours between neighbourhoods (i.e., the intraclass correlation coefficient or ICC)1 was evaluated. Next, a level-1 model that addressed child immigrant status, age and gender was estimated; differences in adolescents’ internalising behaviours by immigrant status were of particular interest. After this, a comprehensive set of family characteristics was included in the level-1 model (including Wave 1 internalising scores), followed by the addition of neighbourhood-level predictors consisting of concentrated disadvantage, immigrant composition and residential stability. This sequence of models was used to determine links between individual- and neighbourhood-level characteristics and Latino immigrant youth’s internalising behaviours. Note that all continuous variables were standardised as z-scores so that the coefficients from the multivariate, multi-level models can be interpreted as effect sizes.

Results

Descriptive statistics

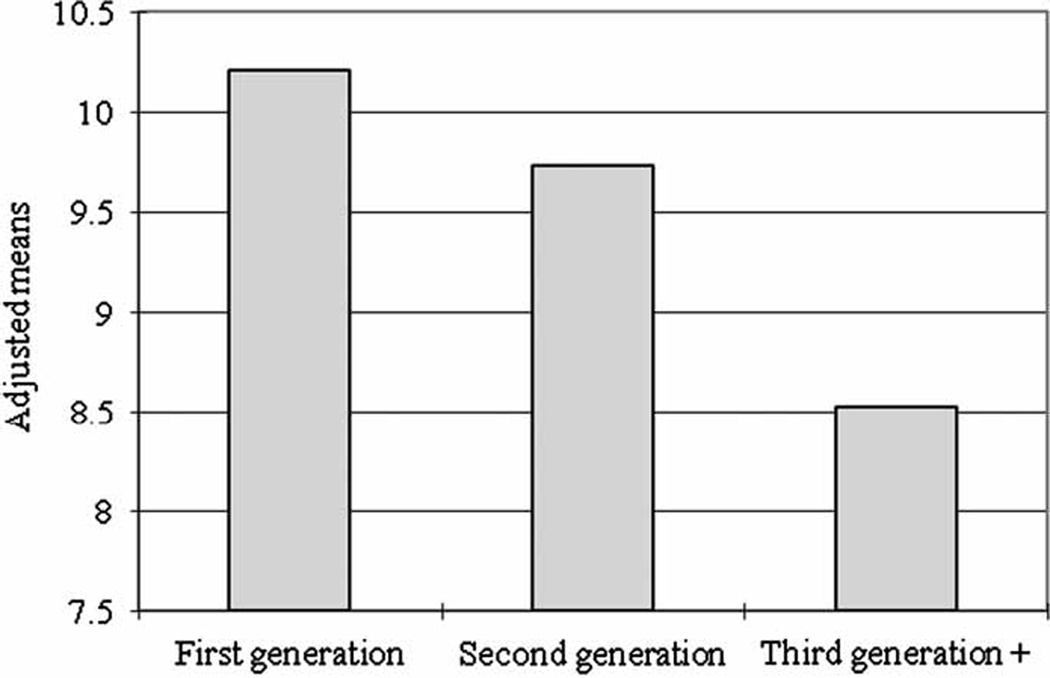

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics about the sample. Specifically, it shows that more than one-third of adolescents had mothers with less than a high school education (37%). The majority of adolescents came from married households (68%). The majority of adolescents were identified as Mexican (76%), less than one-fifth (17%) were identified as Puerto Rican; the rest were from other Latin American countries (7%). Boys and girls were represented in equal proportions. Table 1 also shows that first- and second-generation youth had higher internalising scores compared to third-generation youth at Waves 1 and 2. Results from an ANOVA test indicate that without controlling for anything else, differences among the three groups’ internalising behaviour scores in Waves 1 and 2 are statistically significant (F(2, 828)=5.32, p<0.05, F(2, 828)=3.39, p<0.05, respectively), with a significant difference between first- and third-generation youth. Figure 1 includes adjusted mean internalising scores at Wave 2 by immigrant generation. First- and second-generation youth scored higher than third-generation youth (p<0.01 and p<0.05, respectively), adjusted for youth and family characteristics and Wave 1 internalising scores.

Figure 1.

Depiction of the adjusted mean mental health scores by immigrant generation.

Note: Adjusted for gender, age, Wave 1 internalising behaviour, family income-to-needs ratio, maternal education, marital status and depression. The 95% confidence intervals are 10.74–9.56 for first-generation youth; 10.16–9.28 for second-generation youth; and 9.46–7.82 for third-generation youth.

Significantly more Mexican adolescents were represented in the sample compared to Puerto Rican2 and ‘other’ Latino adolescents; this was true across generations (x2(4, N=1040)=13.99, p<0.01). Second-generation adolescents were significantly younger than their counterparts (F(2, 828)=3.22, p<0.05). First-generation adolescents had lower income-to-needs ratios compared to the other two groups. Results from an ANOVA indicate that differences among the three groups are significantly different (F (2, 907)=41.97, p<0.001). The majority of first- and second-generation adolescents had parents with less than a high school education. In contrast, 52% of third-generation adolescents had mothers with more than a high school education (x2 (8, N=1040)=117.28, p<0.001). The majority of adolescents had parents who were married. First-generation adolescents were more likely to have married mothers (x2 (4, N=1040)=12.86, p<0.01). First-generation adolescents also had the highest proportion of depressed mothers, as measured by the CIDI-SF. In summary, compared to third-generation youth, first-generation adolescents had higher levels of internalising behaviours and were more likely to live in a two-parent household, live with a mother without a high school education and have a mother who was depressed.

The distribution of adolescents living in the various neighbourhoods by immigrant generation is shown in Table 2. Specifically, we examined neighbourhoods with high or low levels of certain characteristics. ‘Low’ and ‘high’ neighbourhoods were created by dividing the data into the bottom and top 50% for each neighbourhood variable. Low-concentrated disadvantage ranges from −1.38 to −0.17. High-concentrated disadvantage includes factor scores from −0.16 to 3.72. Low immigrant concentration ranges from −1.24 to −0.28 and high immigrant concentration ranges from −0.24 to 2.27. Low residential stability ranges from −2.16 to −0.08 and high residential stability ranges from −0.07 to 2.32. Equal proportions of all immigrant generations lived in low- and high-concentration disadvantaged neighbourhoods. The majority of youth in our study, regardless of immigration status, lived in high-immigrant neighbourhoods. Compared to first- and second-generation adolescents, third-generation adolescents are less likely to live in high-immigrant neighbourhoods (x2 (2, N=1040)=26.68, p<0.001). A higher proportion (58% versus 42%) of first-generation adolescents lived in low than high residentially stable neighbourhoods. A lower proportion (41% versus 59%) of third-generation adolescents lived in low- than high-stability neighbourhoods. An equal proportion of second-generation youth lived in low and high residential stable neighbourhoods (x2 (2, N=1040) =11.81, p<0.01). In summary, first-generation youth are more likely to live in high immigrant and low residentially stable neighbourhoods than second- and third-generation youth, with second-generation youth in between.

Table 2.

Proportion of low and high levels of neighbourhood composition for the overall sample and by immigrant generation.

| Variable | First generation (n = 250) |

Second generation (n = 611) |

Third generation (n = 179) |

Total (N = 1040) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentrated disadvantage | ||||

| Low | 47 | 50 | 51 | 49 |

| High | 53 | 50 | 49 | 51 |

| Immigrant concentration | ||||

| Low | 5 | 7 | 18*** | 8 |

| High | 95 | 93 | 82 | 92 |

| Residential stability | ||||

| Low | 58 | 51 | 41** | 51 |

| High | 42 | 49 | 59 | 49 |

Note: ‘Low’ and ‘high’ neighbourhoods were created by dividing the data into the bottom and top 50% for each neighbourhood variable. Low concentrated disadvantage ranges from −1.38 to −0.17. High concentrated disadvantage includes factor scores from −0.16 to 3.72. Low immigrant concentration ranges from −1.24 to −0.28 and high immigrant concentration ranges from −0.24 to 2.27. Low residential stability ranges from −2.16 to −0.08 and high residential stability ranges from −0.07 to 2.32.

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

Immigrant generation and internalising behaviours

Here we report results from our first models that test the links between immigrant generation and internalising behaviours. Results show that first-generation children’s internalising scores were 0.20 standard deviations higher than third-generation adolescents’ scores (β=0.20, p<0.05) after controlling for youth characteristics. We also found that older Latino immigrant youth had significantly higher internalising scores (β =0.06, p<0.05) (see Model 1, Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of heirarchial linear modeling (HLM) results examining the associations between neighbourhood characteristics and immigrant youth mental health (N = 1040).

| Variable | Model 1 Coefficient (SE) |

Model 2 Coefficient (SE) |

Model 3 Coefficient (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.17 (0.07)* | −0.11 (0.08) | −0.08 (0.09) |

| Concentrated disadvantage | - | - | −0.12 (0.11) |

| Immigrant concentration | - | - | −0.04 (0.09) |

| Residential stability | - | - | −0.06 (0.09) |

| Youth immigrant generation | |||

| First generation | 0.20 (0.08)* | 0.13 (0.07)* | 0.07 (0.10) |

| Concentrated disadvantage | - | - | 0.04 (0.15) |

| Immigrant concentration | - | - | 0.07 (0.12) |

| Residential stability | - | - | 0.03 (0.12) |

| Second generation | 0.13 (0.08) | 0.07 (0.07) | 0.06 (0.08) |

| Concentrated disadvantage | - | - | 0.10 (0.12) |

| Immigrant concentration | - | - | 0.00 (0.10) |

| Residential stability | - | - | 0.20 (0.09)* |

| Third generation | Omitted | Omitted | Omitted |

| Youth gender | |||

| Male | Omitted | Omitted | Omitted |

| Female | 0.07 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.02 (0.04) |

| Youth age (years) | 0.06 (0.03)* | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.03) |

| Wave 1 internalising score | 0.40 (0.03)*** | 0.40 (0.04)*** | |

| Family income | |||

| Income/needs ratio | 0.00 (0.03) | −0.02 (0.03) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | Omitted | Omitted | |

| Cohabitating | 0.02 (0.08) | 0.03 (0.08) | |

| Single | −0.02 (0.07) | −0.02 (0.07) | |

| Maternal education | |||

| Less than high school | −0.13 (0.07) | −0.12 (0.08) | |

| Some high school | 0.01 (0.08) | 0.01 (0.08) | |

| High school | 0.00 (0.09) | 0.00 (0.09) | |

| Beyond high school | Omitted | Omitted | |

| College | −0.19 (0.09)* | −0.19 (0.09)* | |

| Maternal mental health | |||

| Depressed | 0.34 (0.07)*** | 0.33 (0.07)*** | |

| Variance components | |||

| Between neighbourhood | 0.05*** | 0.03** | 0.03** |

| Within neighbourhood | 0.80 | 0.63 | 0.62 |

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

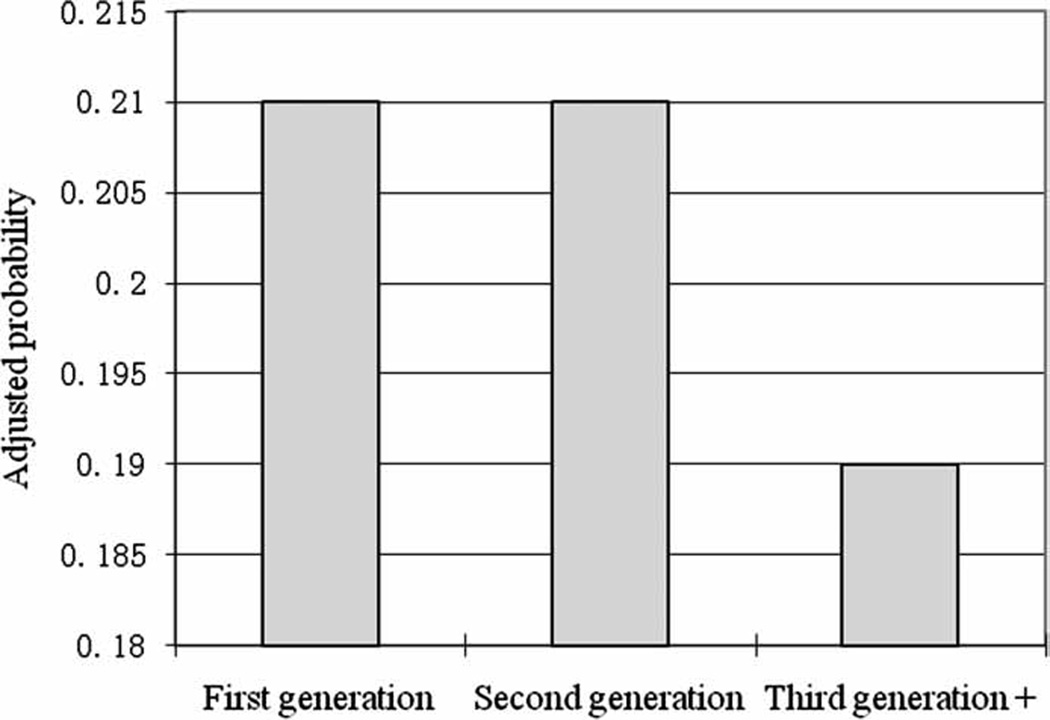

Next we compared the adjusted probability of maternal depressive symptoms across the three generations (see Figure 2). As shown in Figure 2, adjusting for youth and family characteristics, mothers of first- and second-generation youth were more likely to be depressed than third-generation youth (F(2, 903)=4.39, p<0.05). Model 2 explores whether family characteristics explain any differences by immigrant generation that were found in our first model. Results indicated that the immigrant status effect persists even though it is reduced somewhat (see Model 2, Table 3). First-generation youth had significantly higher internalising scores compared to third-generation youth (β =0.13, p<0.05) even after controlling for family characteristics and Wave 1 internalising behaviour scores. Also, adolescents’ internalising scores at Wave 1 are significantly correlated with internalising scores at Wave 2 (β =0.40, p<0.001). As expected, immigrant adolescents of mothers with more education had lower internalising scores (β =−0.19, p<0.05). Adolescents of depressed mothers were significantly more likely to have higher internalising behaviour scores compared to adolescents of non-depressed mothers (β =0.34, p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Depiction of the adjusted probability of maternal depression.

Note: Adjusted for gender, age, Wave 1 internalising behaviour, family income-to-needs ratio and maternal education and marital status. The 95% confidence intervals are 0.217–0.203 for mothers of first-generation youth; 0.215–0.205 for mothers of second-generation youth; and 0.199–0.181 for mothers of third-generation youth.

Neighbourhood characteristics and immigrant youth internalising behaviours

Results for the unconditional HLM model indicate significant between-neighbourhood variation in Hispanic immigrant adolescents’ internalising behaviours, with an intraclass correlation of 6%. This variation allows for further exploration of neighbourhood effects.

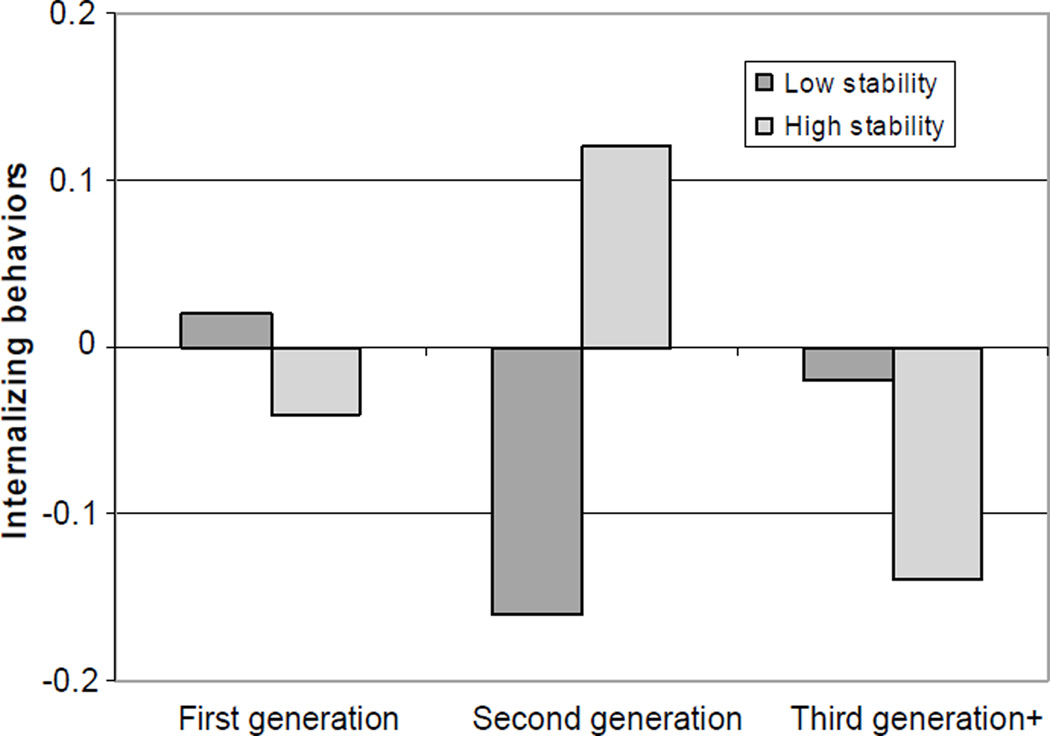

The final set of models was conducted using multilevel analyses and included three neighbourhood variables: concentrated disadvantage, immigrant concentration and residential stability (see Model 3, Table 3). These sets of analyses allowed us to identify links between neighbourhood level characteristics and internalising behaviours while controlling for individual- and family-level variables.3 The results showed that youth’s internalising scores at Wave 1, maternal depressive symptoms and maternal education continued to be significant predictors of adolescents’ internalising scores at Wave 2 (β =0.40, p<0.001; β =0.33, p<0.001; β =−0.19 and p<0.05, respectively). No main effect was found among the three neighbourhood predictors. The addition of neighbourhood-level predictors caused the first-generation coefficient to become non-significant. In other words, the main effect found in our previous models for first-generation youth disappeared after controlling for neighbourhood conditions. The results were never significant for second-generation youth. In addition, an interaction between residential stability and child immigration status was found. The association of residential stability with adolescents’ internalising behaviours differed by generational status (β =0.20, p<0.05). Figure 3 illustrates these associations. Second-generation youth living in neighbourhoods with higher residential stability were more likely to have higher internalising scores than those in neighbourhoods with lower residential stability. For first-generation youth, residential stability significantly affected an adolescent’s internalising scores. As shown in Figure 3, higher levels of residential stability were associated with lower levels of internalising behaviours for third-generation youth, although the association was not statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Depiction of the differential effect of neighbourhood residential stability by immigrant generation.

Note: Standard deviations in the y-axis. The 95% confidence intervals are 0.26 to −0.22 in low-residential-stability neighbourhood and 0.20 to −0.28 in high-residential-stability neighbourhood for first-generation youth; 0.02 to −0.34 in low-residential-stability neighbourhood and 0.30 to −0.06 in high-residential-stability neighbourhood for second-generation youth; and 0.16 to −0.20 for low-residential-stability neighbourhood and 0.04 to −0.32 in high-residential-stability neighbourhood for third-generation youth.

Discussion

Links between neighbourhood context and youth well-being are being studied (Raudenbush and Sampson 1999), although teasing out the effects of family processes (e.g., parenting), SES and other family- and neighbourhood-level characteristics has been difficult due to selection bias and study design. Associations between neighbourhood characteristics (e.g., income) and youth mental health have been examined, but data sets not designed to represent families nested within neighbourhoods are often used (Klebanov et al. 1997, Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000). Furthermore, there is a lack of focus on longitudinal data that centre on Latino immigrants – a growing segment of the population. Our study addressed these gaps by identifying links between Latino adolescents’ immigration status and youth-, family- and neighbourhood-level characteristics as well as internalising behaviours based on parent reports.

We found that first-generation adolescents had significantly higher internalising behaviour scores compared to third-generation adolescents. Older adolescents were also significantly more likely to have higher internalising behaviour scores. Although some evidence suggests that first-generation youth possess protective factors, such as two-parent homes, they also experience stressors that may make them more vulnerable to mental health problems. Unlike second- and third-generation youth, first-generation youth may have to grapple with language issues, pressure to adapt to the host culture, low SES (Harris 1999) and possibly legal status.

Adolescents of depressed mothers also exhibited higher internalising behaviours even after controlling for neighbourhood-level characteristics. According to the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2002), Latino mothers have a higher lifetime prevalence of depression compared to other racial and ethnic mothers; this is especially so for Latino mothers experiencing poverty and lack of access to health care. Our preliminary analysis shows that mothers of first- and second-generation youth are more likely to be depressed than mothers of third-generation youth. Given the evidence showing a link between maternal depression and youth mental health (Petterson and Albers 2001, Gotlib and Goodman 2002, Ensminger et al. 2003, Hammen and Brennan 2003) and the findings revealed in the present study, it will be necessary to control for maternal depressive symptoms when examining links between immigrant generation and youth’s internalising behaviours to better understand the mechanism through which maternal depression impacts immigrant youth mental health. On a positive note, mothers with higher education reported significantly lower internalising behaviours (i.e., better mental health) in their immigrant youth.

Results from the multilevel analyses showed a significant (6%) between-neighbourhood variation, which suggests that differences in the depressive and anxious behaviours of Latino adolescents in this study can be explained by neighbourhood characteristics. This result would be consistent with other studies (Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000) on neighbourhood effects that show neighbourhood effects are small to modest and account for 5–10% of the variance in child and adolescent outcomes.

After controlling for family and neighbourhood characteristics, results indicate that the effect of Wave 1 internalising behaviours on youth internalising behaviours persisted. However, after neighbourhood characteristics are controlled for, these generational differences disappeared. Previous studies (Bender 2007) have shown that untreated mental health needs tend to persist over time. Although we did not assess mental health service use, the literature (Kataoka et al. 2002) suggests that the majority of child and youth mental health needs go unmet. First-generation youth’s access to mental health services may be even more limited. This will be an important variable to account for in future studies.

Results from our multilevel model that controlled for neighbourhood characteristics showed an interaction between adolescent immigration status and residential stability of neighbourhoods. While residential stability has been shown to be an indicator of positive psychological and physical outcomes (Boardman 2004), some evidence indicates that residential stability mixed with other neighbourhood characteristics (e.g., low neighbourhood affluence) is associated with poor health outcomes (Browning and Cagney 2003). We found that for second-generation youth in our study, high residential stability was associated with worse mental health outcomes. We suggest that second-generation adolescents negotiate multiple worlds: immigrant parents, immigrant neighbourhoods and US-born frames of reference. In other words, second-generation adolescents tend to live between immigrant and US experiences (Suarez-Orozco and Suarez-Orozco 1995). Unlike first-generation adolescents who were born outside the USA, second-generation adolescents are native-born with native-born rights (e.g., automatic citizenship) and native-born experiences. However, having at least one immigrant parent separates them both from first-generation adolescents and from third-generation adolescents who live in a US-born family. Researchers refer to these adolescents as living within mixed status parentage and suggest that they may experience tension between immigrant and native identities. Children of immigrants are often told by their parents how fortunate they are and are given a clear picture (often negative) of what life in the homeland was like. In comparison, adolescents whose parents are born in the USA are less likely to have a family homeland story (Suarez-Orozco and Suarez-Orozco 1995). Thus, adolescents who were born in the USA and had at least one foreign-born parent (that is, the second generation) may feel both immigrant and native references. Living in a place where residential instability is high may also be perceived as having reduced opportunities for upward mobility.

Although previous studies (Gil et al. 1994, Kwak 2003) have pointed to acculturation as an explanation for differences in mental health outcomes among immigrant youth, we suggest that the process is more complex collectively than at the individual level. Therefore, understanding acculturation requires a more careful examination of the context in which these youth grow and develop. The present study is among the few that aim to identify the complex factors impacting youth mental health. For example, we suggest that differences in immigrant youth mental health and the differences found here can be linked to the context in which these adolescents live. First-generation adolescents may move into ‘receiving’ neighbourhoods that are composed primarily of other arriving Latino immigrant families and where residential stability is low. Given the economic constraints and other factors (e.g., immigration status), these high-immigrant, low-residential-stability neighbourhoods tend to be the only choice for arriving families. In contrast, stressors may increase as families move out of these receiving neighbourhoods.

Limitations

We believe this study makes a number of important contributions; however, four limitations must be noted. First, the outcomes of interest are based on parental reports which may be inherently biased and potentially influenced by parenting values and parental mental health. To address this limitation, we controlled for caregiver depressive symptoms in our multivariate models. Data on parenting values, however, were not available. Second, generalisability of the results beyond large immigrant cities such as Chicago must be acknowledged. The analysis was limited to the city of Chicago, which was ranked the third-largest city in the USA in 1990, after New York and Los Angeles, and also has a large immigrant population as the larger cities do (Gibson 1998). These factors make it difficult to generalise the results to smaller cities in the USA and to other cities where residential stability might not only be seen as a benefit but may also provide protective factors among minorities (Warner and Rountree 1997). However, given the rates of mental health diagnoses and risk factors observed among Latino and other immigrant youth in large urban cities (Yeh et al. 2002), it is reasonable to expect to find similar results among other immigrant youth (e.g., Asian immigrant youth) in large immigrant cities such as San Diego (Yeh et al. 2002, Driscoll et al. 2008). These results may also be extended to other countries that experience a high influx of immigrants, for example in Europe where second-generation Turkish immigrant youth do not reap all of the same benefits as second-generation immigrants from other countries (e.g., Morocco) and may experience poorer mental health as a result (Crul and Vermeulen 2003). However, the political and social climate of the host country may have an impact on the well-being of its immigrant populations (Nolan 2009) and should therefore be examined further, as should disparities in perception across immigrant groups to help explain (e.g., why second-generation Latino immigrant youth in the current study fared worse compared to first- and third-generation Latino immigrant youth).

A third limitation is the issue of neighbourhood clusters and their reliability as proxies for neighbourhood experience among Latino children in Chicago. The census tracts selected to represent neighbourhood clusters in this study may not reflect the area boundaries that members of those tracts define as neighbourhoods and may not fully capture the lived experiences of Latino immigrant youth in Chicago. Therefore, efforts should be made to define neighbourhoods using communities and neighbourhoods whose boundaries are based on the perceptions of residents and that take into account other defining neighbourhood features that impact youth experiences and well-being (Rankin and Quane 2002).

Last is the issue of selection bias. Attempts were made to address this issue by including covariates that might be related to participants’ neighbourhood choices in the model. However, there may be other variables that were not collected in the study but might be related to neighbourhood choice. Therefore, causal inference based on our findings should not be made.

Implications

Few studies on immigrants have considered links between neighbourhood residence and immigrant status. Additional studies are necessary to understand how context affects immigrant adolescents’ mental health outcomes on the global level. Nonetheless, these findings suggest that adolescent offspring of immigrants in the USA face multiple risks including marginalisation, which is often encountered by immigrant populations, and limited neighbourhood resources, which is often found in economically impoverished neighbourhoods. Children of immigrants in the USA may experience cumulative disadvantages, which may be manifested through depressive and anxious behaviours. Acculturation is often cited as an explanation for differences in mental health outcomes among immigrant youth (Gil et al. 1994). The current study goes beyond acculturation measures to examine how neighbourhood context impacts immigrant youth’s mental health. As shown here, residential stability is associated with poorer mental health in second-generation immigrant youth. Given that programmes and interventions can be offered in targeting communities, a neighbourhood that seems to be well established and has a high concentration of second-generation immigrant youth might be an ideal location for implementing a mental health intervention.

However, given the important role maternal mental health plays in youth wellbeing, interventions at the individual and neighbourhood levels are clearly needed to help adolescents, their families and their communities address the mental health needs of this country’s immigrant youth.

Key messages.

While neighbourhood characteristics may help explain individual differences among the youth in our study, those same characteristics may interact with individual characteristics (e.g., immigrant generation) as shown in our study.

The experiences of second-generation immigrant youth may differ in significant ways from the experiences of first- and third-generation youth because of the unique perspectives that may result from living between worlds.

The experiences of second-generation immigrant youth in our study may reflect those found among other second-generation immigrant youth in large urban cities in the USA and in other immigrant countries.

Additional individual and neighbourhood variables should be further explored to more fully explain the mental health disparities across immigrant generations.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the primary funders of PHDCN, including the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the National Institute of Justice and the National Institute of Mental Health. Additional support for this study was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health’s Science and Ecology of Early Childhood Development Initiative. Additional support was provided to the first author by the RAND Corporation and the Labor and Population Department and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Minority Supplement (R01HD41486-01S1). The findings reported in this paper do not necessarily represent the views of the funders. We are also grateful to Felton Earls, Rob Sampson, Steve Raudenbush, and our other PHDCN colleagues for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

The intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated by summing the between- and within-neighbourhood components produced by the unconditional HLM model with random effects and dividing the sum by the between-neighbourhood variance.

First-generation Puerto Ricans were grouped with Mexicans and other Latinos for the following reasons. First, first-generation Puerto Rican are different from first-generation Latino youth because they are automatically considered as the US citizens, a fact that creates differential access to resources if first-generation immigrant youth are not documented. By definition, second- and third-generation youth are citizens and also likely to be similar in terms of language and acculturation (e.g., first-generation are more likely to speak Spanish primarily). Second, sample size limited our ability to conduct separate analyses for the various Latino subgroups.

All neighbourhood variables are continuous.

References

- Aber JL, et al. The effects of poverty on child health and development. Annual Review of Public Health. 1997;18:463–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Sucoff CA. The neighborhood context of adolescent mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;37:293–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiser M, et al. Poverty, family process and the mental health of immigrant children in Canada. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(2):202–227. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender E. Diagnosis, treatment of youth for depression fell after FDA alert. Psychiatry News. 2007;42(12):1. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, et al. Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(10):1673–1679. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman JD. Stress and physical health: the role of neighborhoods as mediating and moderating mechanisms. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;58(12):2473–2483. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MH, Pickles AR. Influence of maternal depressive symptoms on ratings of childhood behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25(5):399–412. doi: 10.1023/a:1025737124888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ. The effects of poverty on children. The Future of Children. 1997;7:55–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Cagney KA. Moving beyond poverty: neighborhood structure, social processes, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(4):552–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Neighborhood context and racial differences in adolescent sexual behavior. Demography. 2004;41(4):697–720. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N, et al. Parental interactions with Latino infants: variation by country of origin and English proficiency. Child Development. 2006;74(5):1190–1207. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capps R, et al. The health and well-being of young children of immigrants. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cauthen NK, Dinan KA. Immigrant children: America’s future. New York, NY: National Center for Children in Poverty; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The health of minority women fact sheet: women’s health week focuses on minority females. Washington, DC: National Women’s Health Information Center; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale PL, et al. Neighborhood and family influences on the intellectual and behavioral competence of preschool and early school-age children. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Aber JL, et al., editors. Neighborhood poverty: context and consequences for children. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Russell Sage; 1997. pp. 79–118. [Google Scholar]

- Crul M, Vermeulen H. The second generation in Europe. International Migration Review. 2003;37(4):965–986. [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I, Roberts RE. Relations of depression, acculturation, and socioeconomic status in a Latino sample. Latino Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1997;19(2):230–238. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll AK, Russell ST, Crockett LJ. Parenting styles and youth well-being across immigrant generations. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29:185–209. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK. Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Development. 1994;65(2):296–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmelech Y, et al. Children of immigrants: a statistical profile. New York, NY: National Center for Children in Poverty; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, et al. School and neighborhood characteristics associated with school rates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38(1):55–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger ME, et al. Maternal psychological distress: adult sons’ and daughters’ mental health and educational attainment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:1108–1115. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000070261.24125.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauth R, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Welcome to the neighborhood? Long-term impacts of moving to low-poverty neighborhoods on poor children’s and adolescents’ outcomes. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17(2):249–284. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. The effect of maternal depression on maternal ratings of child behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21(3):245–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00917534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fix M, Zimmermann W. Assessing the new federalism policy, Brief A-55. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 1999. All under one roof: mixed-status families in an era of reform. [Google Scholar]

- Formoso D, Gonzalez NA, Aiken LS. Family conflict and children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior: protective factors. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(2):175–199. doi: 10.1023/A:1005135217449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Coll CT, et al. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67(5):1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson C. [Accessed 21 May 2012];Population of the 100 largest cities and other urban places in the United States. 1998 [online]. Available from: http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0027/twps0027.html.

- Gil AG, Vega WA, Dimas JM. Acculturative stress and personal adjustment among Hispanic adolescent boys. Journal of Community Psychology. 1994;22(1):43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Glover SH, et al. Anxiety symptomatology in Mexican-American adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1999;8(1):47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Goodman SH. Introduction. In: Goodman SH, Gotlib IH, editors. Children of depressed parents: mechanisms of risk and implications for treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Guo G, Harris KM. The mechanisms mediating the effects of poverty on children’s intellectual development. Demography. 2000;37(4):431–447. doi: 10.1353/dem.2000.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Brennan PA. Severity, chronicity, and timing of maternal depression and risk for adolescent offspring diagnoses in a community sample. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:253–260. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harker K. Immigrant generation, assimilation, and adolescent psychological wellbeing. Social Forces. 2001;79(3):969–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM. The health status and risk behavior of adolescents in immigrant families. In: Hernandez DJ, editor. Children of immigrants: health, adjustment, and public assistance. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. pp. 286–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez DJ. Demographic change and the life circumstances of immigrant families. The Future of Children. 2004;14(2):17–49. [Google Scholar]

- Infoplease. [Accessed 6 Apr 2009];Hispanic Americans: census facts. 2009 [online]. Available from: http://www.infoplease.com/spot/hhmcensus1.html. [Google Scholar]

- Kao G. Hernandez DJ. Children of immigrants: health, adjustment, and public assistance. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. Psychological well-being and educational achievement among immigrant youth; pp. 410–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, et al. The World Health Organization composite international diagnostic interview, short form (CIDI-SF) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1998;7:172–185. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99:1548–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanov PK, et al. Are neighborhood effects on young children mediated by features of the home environment? In: Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood poverty: context and consequences for children. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Russell Sage; 1997. pp. 119–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak K. Adolescents and their parents: a review of intergenerational family relations for immigrant and non-immigrant families. Human Development. 2003;46:115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(1):309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Xue Y, Brooks-Gunn J. Immigrant differences in school-age children’s verbal trajectories: a look at four racial/ethnic groups. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1359–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipman EL, Offord DR. Psychosocial morbidity among poor children in Ontario. In: Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Consequences of growing up poor. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. pp. 239–287. [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Prelow HM. Externalizing and internalizing problems in low-income Latino early adolescents: risk, resource and protective factors. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2004;24:250–273. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Sandfur G. Growing up with a single parent: what hurts, what helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Meurs I, et al. Intergenerational transmission of child problem behaviors: a longitudinal, population-based study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:138–145. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318191770d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan B. Promoting the well-being of immigrant youth. University College Dublin, Working Paper 09/09; 2009. Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, King NJ. Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of internalizing problems in children: the role of longitudinal data. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62(5):918–927. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin BH, Quane JM. Social contexts and urban adolescent outcomes: the interrelated effects of neighborhoods, families, and peers on African-American youth. Social Problems. 2002;49:79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, et al. HLM 5: hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Sampson RJ. Ecometrics: toward a science of assessing ecological settings, with application to the systematic social observation of neighborhoods. Sociological Methodology. 1999;29:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Sobhan M. Symptoms of depression in adolescence: a comparison of Anglo, African, and Hispanic Americans. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1992;21(6):639–651. doi: 10.1007/BF01538736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachter LM, et al. Do parenting and the home environment, maternal depression, neighborhood, and chronic poverty affect child behavioral problems differently in different racial-ethnic groups? Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1329–1338. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petterson SM, Albers AB. Effects of poverty and maternal depression on early child development. Child Development. 2001;72:1794–1813. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Legacies: the story of the immigrant second generation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Groves WB. Community structure and crime: testing social-disorganization theory. American Journal of Sociology. 1989;94(4):774–802. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff J, Raudenbush SW. Social anatomy of racial and ethnic disparities in violence. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(2):224–232. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.037705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Sharkey P. Neighborhood selection and the social reproduction of concentrated racial inequality. Demography. 2008;45(1):1–29. doi: 10.1353/dem.2008.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields MK, Behrman RE. Children of immigrant families: analysis and recommendations. The Future of Children. 2004;14(2):4–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Bacallao M. Acculturation, internalizing mental health symptoms, and self-esteem: cultural experiences of Latino adolescents in North Carolina. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2007;37(3):273–292. doi: 10.1007/s10578-006-0035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, et al. Neighborhood and family influences on young urban adolescents’ behavior problems: a multisample, multisite analysis. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood poverty: context and consequences for children. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Russell Sage; 1997. pp. 62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Markstrom-Adams C. Identity processes among racial and ethnic minority children in America. Child Development. 1990;61(2):290–310. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Orozco C, Suarez-Orozco M. Transformations: immigration, family life and achievement motivation among Latino adolescents. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Varela RE, et al. Internalizing symptoms in Latinos: the role of anxiety sensitivity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:429–440. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth ME, et al. Latent class analysis of child behavior checklist anxiety/ depression in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(1):106–114. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200101000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldfogel J, Craigie TA, Brooks-Gunn J. Fragile families and child well-being. The Future of Children. 2010;20(2):87–112. doi: 10.1353/foc.2010.0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner B, Rountree PW. Local social ties in a community and crime model: questioning the systemic nature of informal social control. Social Forces. 1997;44:520–536. [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, et al. Neighborhood residence and mental health problems of 5- to 11-year olds. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(5):554–563. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh M, et al. Referral sources, diagnoses, and service types of youth in public outpatient mental health care: a focus on ethnic minorities. Journal of Behavioral Services and Research. 2002;29:45–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02287831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu SM, et al. Acculturation and the health and well-being of U.S. immigrant adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33(6):479–488. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00210-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]