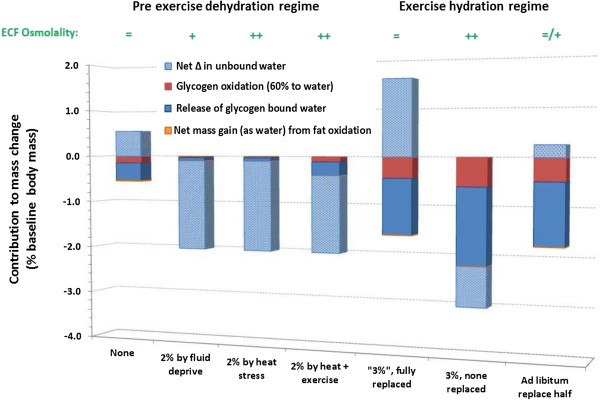

Figure 3.

Indicative contributions of different sources to changes in body mass for hypohydration induced before or during strenuous exercise.Bar A represents starting exercise euhydrated when rehydrated from an overnight fast (14 h), whereas bars B–D represent starting exercise 2% hypohydrated obtained as primary hypohydration (fluid deprivation alone over 24 h: B), heat stress alone (C) or light exercise in the heat (D). Bars E–G each represent strenuous intermittent or endurance exercise sufficient to oxidise 300 g of glycogen in a 70-kg person and produce 3% 'hypohydration’ (mass deficit), with full 'rehydration’ (3% mass restoration: E), no rehydration (F) or ad libitum rehydration (G; see [11]). Within the bars, 'Glycogen bound water’ (solid blue) refers to water that was previously complexed to and possibly within [94] glycogen before its oxidation. This contribution was assumed to be 2.7 times larger than the mass of glycogen oxidised, based on estimations in the literature of 3–4 times larger [95]. 'Unbound water’ (stippled light blue) refers to water that is not bound to glycogen molecules or created during oxidative metabolism. The mass difference from triglyceride metabolism is small (13% net gain, as water), so this component is difficult to see. A 10% energy deficit was assumed with 24 h of primary hypohydration [70]. An additional 111 g of glycogen oxidation in F versus E is based on measurements with 2–4% dehydration during exercise in temperate and hot laboratory environments [30,32], and an additional 30 g is estimated for G versus E. Bars E and G only show the appearance of not summating to 3% gross mass exchange because some of the ingested fluid would cancel out an attenuated mass of glycogenolysis-released water. See text for more interpretation of these differing circumstances and discussion of the implications, suffice to say here that the net volume of free water exchange depends on the hydration protocol used and thus needs to be considered when interpreting physiological, psychological and performance effects of dehydration studies.