SUMMARY

Using 51V magic angle spinning solid-state NMR spectroscopy and Density Functional Theory calculations we have characterized the chemical shift and quadrupolar coupling parameters for two eight-coordinate vanadium complexes, [PPh4][V(V)(HIDPA)2] and [PPh4][V(V)(HIDA)2]; HIDPA = 2,2′-(hydroxyimino)dipropionate and HIDA = 2,2′-(hydroxyimino)diacetate. The coordination geometry under examination is the less common non-oxo eight coordinate distorted dodecahedral geometry that has not been previously investigated by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Both complexes were isolated by oxidizing their reduced forms: [V(IV)(HIDPA)2]2- and [V(IV)(HIDA)2]2-. V(IV)(HIDPA)22- is also known as amavadin, a vanadium-containing natural product present in the Amanita muscaria mushroom and responsible for vanadium accumulation in nature. The quadrupolar coupling constants, CQ, are found to be moderate, 5.0 to 6.4 MHz while the chemical shift anisotropies are relatively small for vanadium complexes, −420 and 360 ppm. The isotropic chemical shifts in the solid state are −220 and −228 ppm for the two compounds, and near the chemical shifts observed in solution. Presumably this is a consequence of the combined effects of the increased coordination number and the absence of oxo groups. Density Functional Theory calculations of the electric field gradient parameters are in good agreement with the NMR results while the chemical shift parameters show some deviation from the experimental values. Future work on this unusual coordination geometry and a combined analysis by solid-state NMR and Density Functional Theory should provide a better understanding of the correlations between experimental NMR parameters and the local structure of the vanadium centers.

Keywords: solid-state NMR, magic angle spinning, MAS, 51V, quadrupolar, chemical shift, EFG, CSA, amavadin, HIDA, HIDPA, non-oxo, eight coordinate

Introduction

Vanadium has a diverse coordination chemistry and can be found routinely in environments with coordination numbers ranging from three to eight giving rise to many complexes that have useful chemical and biochemical properties.1, 2 Even though vanadium is a trace element in biological systems, it is an essential cofactor in a number of enzymes, also acts as an insulin enhancing agent and has been found as a natural product in the mushroom Amanita muscaria.2–8 The biological activity of vanadium complexes and proteins is determined by the specific chemical environment of the vanadium centers. The application of 51V NMR to study solid vanadium-containing complexes that are of biological relevance has grown rapidly in recent years9–25 due to the ability to acquire high quality magic angle spinning spectra of both the central and satellite NMR transitions of the 51V (I = 7/2). Studies have demonstrated that both the quadrupolar coupling and the chemical shift anisotropy, which can be determined from the solid-state NMR spectra, are sensitive to the local vanadium environment and can be used to understand changes in the local molecular orbital structure and ground state charge distribution at the vanadium.9–24 Therefore, it is important to determine the 51V solid-state NMR parameters of less common coordination geometries in vanadium complexes.

In nature, one of the highest concentrations of vanadium can be found in the Amanita muscaria mushrooms.6, 7 Vanadium levels as high as 400 mg/kg of mushroom have been reported.7 The vanadium is found in the mushroom as an eight coordinate complex, amavadin (Figure 1), in a highly distorted cubic geometry that does not include the common V=O bonds.26, 27 While amavadin shows unique redox capabilities including peroxidative halogenation28, 29 and oxygen activation,30 its role in the biological processes of the Amanita mushroom is unknown. Information about the electronic properties of the vanadium center may be important for understanding the chemical properties and the function of this unusual molecule. Furthermore, it is known that the redox potential of the amavadin is different by 100 mV from that of the simpler analog, whereas electron transfer processes to the vanadium are indistinguishable.31

Figure 1.

The structure of a) [PPh4][V(V)(HIDA)2]·CH2Cl2 and b) [PPh4][V(V)(HIDPA)2]·H2O. The structures were obtained from the Cambridge Crystal Structure database; depository names YAPHOM and YAPHUS, respectively. Hydrogen atoms are color coded white, carbon atoms- grey, nitrogen atoms- blue, oxygen atoms- red, and vanadium atoms- green.

The structure of the vanadium in amavadin does not change dramatically upon oxidation. The oxidized amavadin complex and its analog thus offer a unique opportunity to study an eight coordinate vanadium geometry and to compare the effect that such coordination has on the electric field gradient (EFG) and chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) in the solid state. Recently, the role of each steric factor in the unique eight coordinate geometry of the amavadin complex has been explored using DFT calculations, structural analysis and solution 51V chemical shifts.32 These studies revealed that the unusual deshielding of the 51V resonances for amavadin and analogs can be attributed to a number of structural increments from regular substituent effects, and that the largest contribution arises from the non-oxo nature of these complexes.32 The variation that diastereomeric isomers had on the chemical shifts was considered to be minor. In this study, we present 51V solid-state NMR spectra of the oxidized form of the natural product amavadin, (PPh4)[V(V)(HIDPA)2], and one of its analogs, (PPh4)[V(V)(HIDA)2]; HIDPA and HIDA stand for the basic forms of 2,2′-(hydroxyimino)dipropionate and 2,2′-(hydroxyimino)diacetate, respectively. The NMR parameters for the two compounds are discussed in terms of coordination environment and compared to the current body of of 51V solid-state NMR data for other vanadium complexes. Surprisingly, the results reveal moderate quadrupolar coupling constant and small chemical shift anisotropies for both oxidized amavadin and its analog indicative of symmetric electronic charge distribution at the vanadium center. The DFT calculations predict accurately the electric field gradient tensor whereas the computed chemical shift anisotropy tensors show discrepancies with the experiment suggesting unusual electronic environment in these rare eight-coordinate non-oxo vanadium complexes.

Results and Discussion

51V Solid-State NMR Parameters

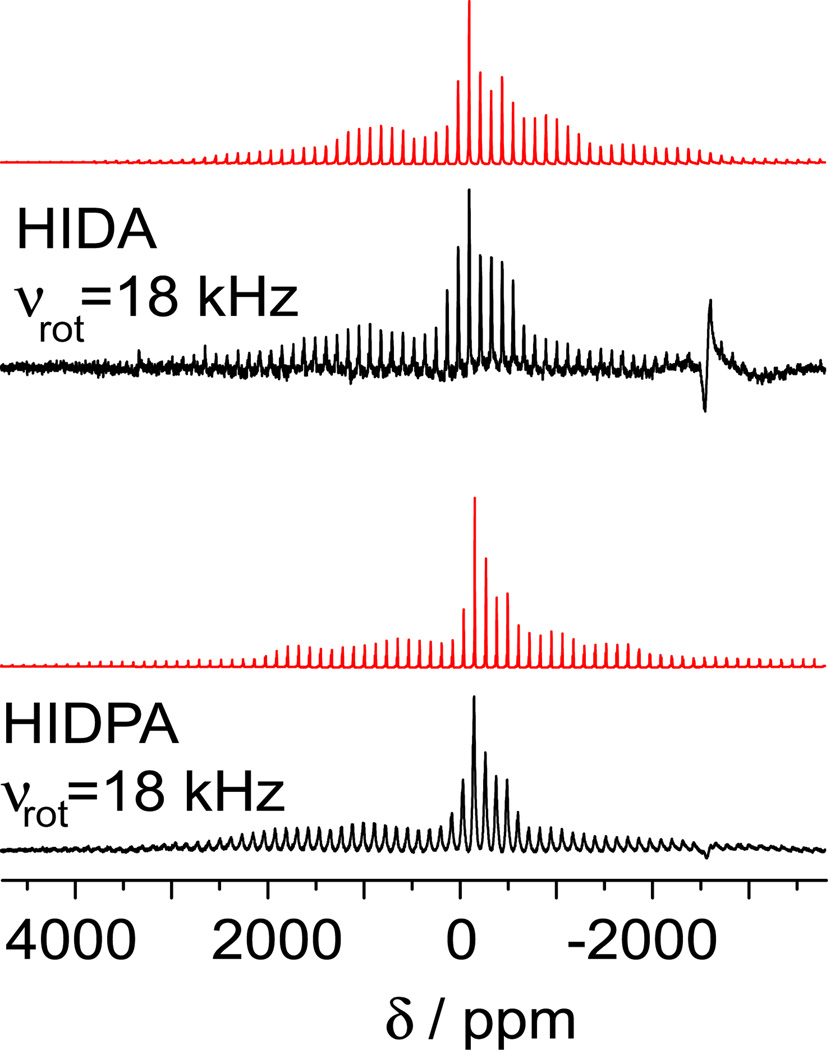

The NMR spectra of the two eight-coordinate complexes acquired at 14.1 T and three magic angle spinning (MAS) frequencies are shown in Figure 2. The spectra are typical of vanadium coordination complexes and contain NMR signal from both the central and satellite transitions. Using SIMPSON,33 numerical simulations of the spectra were performed, and the 51V chemical shift and quadrupolar coupling parameters were extracted, Table 1. The high quality of the fits is illustrated in Figure 3 using the spectra for HIDA and HIDPA complexes acquired with the MAS frequency of 18 kHz. The isotropic chemical shift in the HIDA complex, δiso = −220 ppm while in HIDPA δiso = −268 ppm. These values are significantly less shielded than those observed for seven-coordinate complexes, where the isotropic shifts typically ranged from −570 to −680 ppm. Similarly, in solution the 51V resonances for the oxidized amavadin complex and its analog are reported to be significantly less shielded than in the corresponding six- and seven-coordinate complexes. Specifically, the oxidized form of amavadin, [V(V)(HIDPA)2]−, showed chemical shifts ranging from −281 ppm34 to −252 ppm;35 and for the analog, [V(V)(HIDA)2]-the corresponding shift was −263 ppm.36 Therefore, these compounds exhibit unusual chemical shifts both in solution and in the solid state, and this behavior has been attributed to the unique geometric and electronic structure of these complexes.

Figure 2.

Solid-state 51V NMR spectra of the two complexes obtained at 14.1 T and different MAS rates. The signal observed at −600 kHz is from the copper coil.

Table 1.

Experimental and Calculated 51V Solid-State NMR Parameters for the Eight Coordinate Non-Oxo Amavadin-Type Vanadium(V) Complexes

| Compound | Method (geometry) |

CQ / MHz | ηQ | δiso / ppm | δσ / ppm | ησ | α / β /γ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIDA | Experiment | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | −220 ± 5 | −420 ± 20 | 0.5 ± 0.05 | −45 / 0 / 90 |

| b3lyp/6–311+G(d,p) (X-ray) |

−4.38 | 1.0 | −615 | −131 | 0.426 | ||

| b3lyp/6–311+G(d,p) (optimized) |

5.42 | 0.89 | −561 | −131 | 0.03 | ||

| b3lyp/6–311+G(d,p) | 5.27 | 0.91 | −557 | −136 | 0.04 | ||

| b3lyp/6–311++G | 4.59 | 0.99 | −611 | −136 | 0.04 | ||

| b3lyp/tzvp | −3.51 | 0.65 | −577 | −141 | 0.03 | ||

| PBE1PBE/6–311+G(d,p) | 5.34 | 0.89 | −609 | −115 | 0.02 | ||

| PBE1PBE/6–311++G | 4.66 | 0.96 | −673 | −115 | 0.02 | ||

| PBE1PBE/tzvp | −3.41 | 0.64 | −638 | −120 | 0.02 | ||

| PBEPBE/6–311+G(d,p) | −4.48 | 0.93 | −340 | 245 | 0.08 | ||

| PBEPBE/6–311++G | −4.02 | 0.85 | −363 | 246 | 0.08 | ||

| PBEPBE/tzvp | −2.96 | 0.34 | −354 | 245 | 0.09 | ||

| HIDPA | Experiment | 6.4 ± 0.2 | 0.45 ± 0.1 | −268 ± 0.1 | −360 ± 8 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 90 / 0 / 90 |

| b3lyp/6–311+G(d,p) (X-ray) |

−6.03 | 0.49 | −630 | −102 | 0.47 | ||

| b3lyp/6–311+G(d,p) (optimized) |

7.33 | 0.45 | −572 | −103 | 0.03 | ||

| b3lyp/6–311+G(d,p) | 7.20 | 0.46 | −573 | −109 | 0.03 | ||

| b3lyp/6–311++G | 6.53 | 0.49 | −630 | −108 | 0.03 | ||

| b3lyp/tzvp | 4.63 | 0.55 | −591 | −114 | 0.03 | ||

| PBE1PBE/6–311+G(d,p) | 7.25 | 0.45 | −628 | −85 | 0.03 | ||

| PBE1PBE/6–311++G | 6.44 | 0.49 | −695 | −85 | 0.02 | ||

| PBE1PBE/tzvp | 4.47 | 0.57 | −655 | −90 | 0.04 | ||

| PBEPBE/6–311+G(d,p) | 6.00 | 0.53 | −353 | 251 | 0.07 | ||

| PBEPBE/6–311++G | 5.27 | 0.59 | −376 | 254 | 0.07 | ||

| PBEPBE/tzvp | 3.46 | 0.72 | −364 | 257 | 0.07 | ||

The chemical shift parameters are defined such that |δzz − δiso|≥|δxx− δiso|≥|δyy−δiso|, δiso=(δzz + δyy + δxx)/3, δσ=δzz − δiso, and ησ=(δyy − δxx)/δσ.The components of the chemical shift tensor are δii =(vii - vref)/vref (ii = zz, xx, yy).

The EFG parameters are CQ = eQVZZ/h and ηQ = (VXX − VYY)/VZZ where |VZZ|≥|VYY|≥|VXX|, e is the electron charge and h is Planck’s constant.

Figure 3.

Experimental (black) and simulated (red) spectra of the two complexes obtained while spinning the samples at 18 kHz at 14.1 T.

Smaller isotropic shifts observed for [V(V)(HIDPA)2]− and [V(V)(HIDA)2]− suggest that on average the mixing between the high energy occupied and low energy unoccupied molecular orbitals is better in these eight coordinate complexes than in complexes with lower coordination numbers.37 The anisotropy of the chemical shift is also smaller than that observed typically in seven coordinate complexes, and resembles more the anisotropy of a five- or six-coordinate complex. The smaller anisotropy indicates that the magnitude of the vanadium shielding is similar in all directions, suggesting a relatively symmetric molecular orbital environment at the vanadium atom. Given the fact that these complexes contain no V=O groups, the high symmetry at the distorted cubic vanadium atoms can be readily reconciled.

To rationalize the detected moderate quadrupolar coupling constant, the electronic charge distribution at the vanadium site needs to be analyzed. Based on simple point charge models, vanadium in a site of cubic symmetry will experience no electric field gradient. However, when the ideal symmetry is broken an electric field gradient will be created at the vanadium site. The magnitude of these changes correlates directly to the magnitude of the electric field gradient and therefore, to the measured quadrupolar interaction parameters. Based on the NMR spectra it is determined that the quadrupolar coupling constants for the HIDA and HIDPA complexes are 5.0 and 6.4 MHz, respectively. The asymmetry parameters of the EFG tensor are 0.2 and 0.45 for the HIDA and HIDPA, respectively. These values can be considered average in size; typically the 51V CQ values for coordination complexes studied to date range from ca. 3 MHz to as high as 8.3 MHz. Therefore, it can be concluded that despite the high coordination number, the distribution of charge in the vicinity of the vanadium atom deviates from spherical symmetry.

In addition to the chemical shift and EFG tensor parameters, the Euler angles that define the relative orientation of the two tensors can be found by fitting the spinning sidebands envelope of the satellite transitions. Due to the low signal-to-noise ratio in the outer satellites as well as the lack of well-defined features in the envelope the error on the angles is large. Despite this, it is clear that β is close to 0° in both complexes, placing Vzz along δzz; the angles used in the simulations are listed in Table 1.

DFT Calculations of the NMR Parameters

Quantum chemical calculations of 51V NMR parameters have provided a valuable link between experimental NMR observables and the structure of vanadium complexes.17, 18, 23, 24, 32, 38–42 Table 1 contains the results of calculations performed on the HIDA and HIDPA complexes using three functionals, b3lyp, PBE1PBE, and PBEPBE, and three basis sets, 6–311++G(d,p), 6–311++G, and tzvp as available in the Gaussian03 program.43 The results obtained for the quadrupolar coupling constant and the asymmetry parameters of the EFG tensor for the HIDPA complex are in good agreement with experiment. The CQ calculated for the HIDA complex is also well reproduced while the ηQ parameter shows a greater deviation from experiment. Calculations using b3lyp and PBE1PBE functionals and 6–311+G(d,p) or 6–311++G basis sets yield good agreement with experiment while calculations performed with PBEPBE functional (all basis sets) and those using a tzvp basis set (all functionals) underestimate the CQ. All calculations were performed using a single molecule without the inclusion of counterions. Given the good agreement of the EFG calculations with the experiment, we conclude that the EFG at the vanadium is almost completely determined by the vanadium complex. Longer-range influences from counterions and neighboring complexes are negligible and need not be considered further.

Unlike the EFG calculations, the calculated magnetic shieldings (where the shieldings have been converted to chemical shifts as described in the methods section) show greater deviations from the experimental values. The calculated δiso values are significantly more shielded than the experimental results while the calculated anisotropies of the tensor are smaller than the experimental values. The worst agreement between experiment and theory is reached when PBEPBE functional is used: the sign of the chemical shift anisotropy is incorrect (Table 1). Further analysis of the computational results reveals that the largest discrepancies arise from the δxx and δyy components of the tensor, both of which are much more shielded than experimentally observed. To understand the possible source of the error we assume that the calculated orientation of the EFG in the molecular frame is correct; this is a good assumption given the success of the EFG calculation. Using our experimental Euler angles we note that δzz should be parallel to Vzz, i.e. β = 0°. According to the calculations, Vzz is oriented along the approximate N-V-N axis, see Figure 4. The shielding along this axis, δzz, is dictated by the molecular orbitals in the perpendicular plane. In the case of HIDA, this plane consists mostly of bonds between the vanadium and the carboxy oxygens. Conversely, the δxx and δyy components of the chemical shift tensor contain contributions from the oxyamine portion of the ligands. Since it is δxx and δyy that are reproduced less well in the calculations, it is likely that it is the coordination of the oxyamines to the vanadium that is the source of the discrepancies in the calculations. Similar behavior was reported in a previous study of vanadium complexes with oxyamine ligands where substantial errors were observed for δzz, the chemical shift component perpendicular to the oxyamine plane.24, 32 The fact that even at this level of theory difficulties are encountered in describing the interaction between the three-membered oxyamine-vanadium is consistent with the well-known problems with calculations of these strained compounds. The lower calculated anisotropies suggest that the molecule is less symmetric than the models used and indicate that the calculations underestimate the bonding between the vanadium and the oxyamine unit when using the X-ray structures.

Figure 4.

The orientation of the EFG tensor with respect to the HIDA complex as determined by the DFT calculations. Hydrogen atoms are color coded white, carbon atoms- grey, nitrogen atoms- blue, oxygen atoms- red, and vanadium atoms- green.

Interpreting 51V NMR Parameters in terms of Molecular Structure

From an NMR and chemistry perspective the results for the non-oxo eight-coordinate oxidized amavadin-type complexes presented here provide a key data set that allows us to expand our understanding of the dependence of the 51V anisotropic solid-state NMR parameters on the vanadium coordination environment. These studies are the first in which vanadium compounds lacking a V=O group and exhibiting eight-coordination geometry are investigated by solid-state NMR, and thus will test the possibility that NMR can assist chemists in the characterization and identification of new vanadium-containing compounds. For the 51V NMR to be used as a predictive tool typically the NMR parameters for related series of compounds are compiled into a database, and empirically observed trends are subsequently used for building structural models for new compounds. In order to establish such correlations between 51V NMR parameters and chemical structures a wide range of vanadium compounds of different coordination geometries and ligand sets has to be investigated. We have started building such a database using 51V solid-state NMR to characterize vanadium(V) in an extensive range of chemical and geometric environments from various classes of compounds and with different coordination geometries,17, 23, 24 and can therefore examine the current results together with those from our prior work. The most fundamental correlations that are often made are those between the chemical shift anisotropy (or the isotropic chemical shift), or the CQ, and the coordination number of the atom of interest. For example, such correlations for 29Si have provided a valuable method for characterizing the local environment of different silicon atoms in a range of silicate materials; similarly correlations for aluminum have been observed.44 Additionally, geometric factors such as bond angle and length often produce trends in the NMR parameters such as those observed for 17O in glasses and 31P in phosphates.45, 46 The situation becomes more complex for transition metals which can have a wider range of geometries and coordination numbers, but some trends have also been suggested such as for 139La coordination complexes and even 51V in inorganic vanadia compounds.47, 48

In solution state a number of correlations between isotropic chemical shifts and coordination geometry have been reported for various vanadium complexes, although the empirical relationships are typically observed within classes of related molecules.1, 9, 49–51 For example, the chemical shifts of oxovanadates generally follow the degree of polymerization with the systematic changes in the 51V shifts between monomer, dimer, tetramer, and pentamer.1 Similarly, the chemical shifts for oxovanadium(V) complexes with diethanolamine and derivatives follow a pattern that varies with the substitutions on the diethanolamine.49, 50 Chemical shift changes for vanadium alkoxides have been observed to vary with the steric bulk of alkoxides, and are found to be indicative of the coordination number of the vanadium.9 Solution studies of peroxovanadium(V)1 and hydroxylamine1, 51 complexes have demonstrated that both of these classes of compounds are significantly different from the more common six-coordinate coordination complexes and are akin to molecules investigated in this work.

All of the above correlations in the solid state and in solution are typically established in a series of related compounds or in materials where the identity of the coordinating atoms or ligands is preserved, and only geometric-structural changes occur. In an attempt to decipher possible empirical correlations between the 51V solid-state NMR parameters and the molecular structure features we have analyzed the aggregate of solid-state NMR data that we have generated in this work and in our several prior studies.17, 23, 24 These studies span a broad range of bioinorganic vanadium(V) complexes with different coordination numbers and different ligand sets, and thus represent the existing information available without any attempt to divide the molecules into the different classes of complexes.

Figure 5 shows a plot of a derived quadrupolar parameter versus the coordination number for a majority of the vanadium complexes for which 51V solid-state NMR data are available.9, 17, 23–25, 52, 53 The derived quadrupolar parameter, , takes into account the asymmetry parameter of the EFG tensor as well as CQ and is useful because it can be extracted based solely on the second-order quadrupolar shift.9 Perhaps not surprisingly, there is no clear trend in these graphs that would provide a useful correlation between the NMR observables and coordination number. For the quadrupolar coupling, the lowest values are observed for four and six coordinate complexes. This is likely the result of the fact that vanadium coordination geometry is close to tetrahedral and octahedral in these complexes. However, quadrupolar parameters close to 7 and 8 MHz can also be observed for four and eight coordinate vanadium, similar magnitudes as seen for the other coordination numbers. Clearly, the ability of vanadium to form non-ideal coordination geometries leads to a wide range of quadrupolar values.

Figure 5.

Plots of the NMR parameters as a function of the vanadium coordination number (CN).

Figure 5 also shows the chemical shift parameters, δσ and δiso, versus the coordination number. Interestingly, these graphs show more clustering as a function of the coordination number. The chemical shift anisotropy, δσ decreases systematically as coordination number increases; excluding the eight coordinate complexes. This would be consistent with what has been reported for vanadia-based inorganic solids, where it has been observed that typically six-coordinate vanadium has larger chemical shift anisotropies than the four-coordinate species.47 The trend is broken by the eight-coordinate complexes studied here, and may reflect the fact that the electronic and geometric environments are different from those in most compounds studied previously. Alternatively, the current findings might indicate that the bonding environment in the vicinity of the vanadium is better described as six-coordinate, i.e., the oxyamine fragment should be treated as a single coordination position, an argument also put forth previously in the literature for oxyamine-type complexes.51 While clustering of the δiso values is also present, there is no linear trend in δiso as a function of coordination number. The results suggest that for vanadium δσ, and not δiso, is the more useful measure of the vanadium local structure, as has been observed previously.17, 18, 24

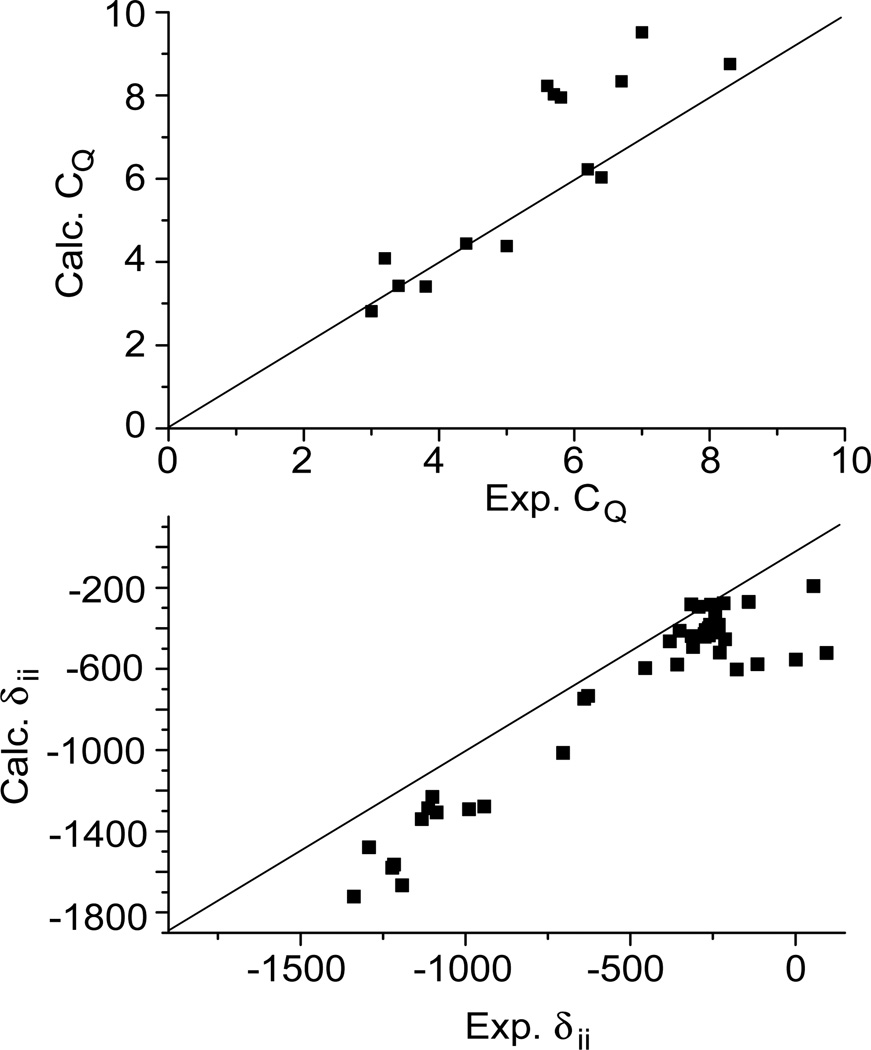

Given the spread in the NMR parameter database as a function of coordination number, it is desirable that calculations be obtained as a link between the experimental parameters and the local structure in the vicinity of the vanadium. As has been shown above and in previous studies, DFT calculations of NMR parameters can be reasonably accurate when standard basis sets and functionals are used. Figure 6 shows a plot of experimental CQ and δii (ii = xx,yy,zz) values for all the complexes that we have addressed previously by solid-state NMR and DFT calculations; calculations were performed using b3lyp functional and 6–311+G** or 6–311+G basis sets in Gaussian.17, 23, 24 From these plots it is evident that good agreement can be achieved between experiment and calculation. Typically the CQ is predicted to within 15 % of the experimental values, while the δii values are underestimated by 50 to 200 ppm. It is interesting that for the chemical shift calculations the errors seem to be systematic. It has been previously reported that the typical agreements between experimental results and theoretical chemical shift predictions are of the order of 100 ppm for 51V.23, 39 Previous investigations using different levels of theory have also revealed that, after a certain threshold, larger basis sets did not significantly improve the chemical shift parameters.23 This suggests that the systematic deviation either arises from a fundamental ill representation in the calculations of a particular structural unit, or from a systematic issue in the atom positions obtained from single crystal X-ray diffraction. The relatively low resolution of the X-ray structure of amavadin complexes34 may be one possible source of the discrepancy between the experimental and calculated shieldings. However, the rigidity of the ligand leaves little room for changes in the geometry of this complex. Indeed, DFT calculations using geometry-optimized structures have not improved the accuracy of the computed shieldings (Table 1). The possibility that some of the error is due to the calculated shielding of the reference compound VOCl3, should also be considered, although this error is not expected to account for all of the observed discrepancies. Combined these results provide important benchmark data for which the analysis using both theory and experiment can be developed for future applications.

Figure 6.

Plots of the experimental vs. calculated NMR parameters for all vanadium(V) complexes studied by solid-state NMR and DFT computational methods. The solid lines represent perfect agreement between calculation and experiment.

Experimental Section

Materials and methods

Vanadyl acetylacetonate, [VO(acac)2] (99.99%), 2-bromopropionic acid (≥99%), bromoacetic acid (≥99%), tetraphenylphosphonium chloride (98%), zinc acetate dihydrate (98%) and Dowex HCR-W2 strong acid resin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid, ceric ammonium nitrate ([NH4]2[Ce(NO3)6], 98%) and hydroxylamine hydrochloride (NH2OH·HCl, 98%) were purchased from Fisher Scientific. All compounds were used as received, and distilled deionized water was used in all syntheses. The ligands HIDPA = 2,2′-(hydroxyimino)dipropionate and HIDA = 2,2′-(hydroxyimino)diacetate and corresponding vanadium(IV) and vanadium(V) complexes were prepared with slight modifications of the reported syntheses.34, 35, 54–58

Ligand synthesis: HIDA = 2,2′-(hydroxyimino)diacetate

Hydroxylamine hydrochloride (3.47 g, 0.05 mol) was neutralized with 10 mL of 5 M NaOH. Bromoacetic acid (13.90 g, 0.10 mol) was slowly neutralized with 20 mL of 5 M NaOH maintaining the solution temperature at or below 0°C. The hydroxylamine solution was then chilled to ~0°C in a salt/ice bath. The bromoacetic acid solution was then added dropwise to the hydroxylamine solution, and care was taken to maintain the solution mixture at 0°C. An additional 20 mL of 5 M NaOH were slowly added to the mixture, which was then allowed to stand for ~72 hours in a refrigerator (~4°C).

The mixture was then acidified to pH 4.0 with 1 M HCl. To this solution zinc acetate dihydrate (11.0 g, 0.0684 mol) was added. The mixture was allowed to stand overnight at ambient temperature. The resulting zinc complex was then filtered off, washed with 10 mL of ice-cold water and dried over P2O5.

The zinc complex (3.0 g, 0.014 mol) obtained as described above was dissolved in 25 mL of water by dropwise addition of concentrated HCl until the solution was clear. This solution was loaded onto an acidic Dowex HCR-W2 cation exchange resin (column size 2.5 cm × 30 cm) and eluted with 0.2 M NaOH. The fraction containing the product was dried in a rotary evaporator at ambient temperature over P2O5. The 1H NMR spectra were similar to those reported previously.34, 35, 54–57

HIPDA = 2,2′-(hydroxyimino)dipropionate

HIPDA was synthesized using the above procedure except that 2-bromopropionic acid was employed in place of bromoacetic acid. The product was confirmed using 1H NMR spectroscopy; this is a low yielding reaction (<10% yield), and the material formed is less pure than in the reaction producing the HIDA ligand.

[Ca(H2O)5][V(IV)(HIDA)2]·H2O

The compound was prepared with [VO(acac)2] (2.65 g, 10.0 mmol), HIDA (3.15 g, 21.1 mmol) and CaCl2 (1.11 g, 10.0 mmol) in H2O (100 mL). Blue prismatic crystals were obtained from H2O–isopropyl alcohol using the slow liquid-diffusion technique at 293 K as described previously.58

[Ca(H2O)5][V(IV)(HIPDA)2]·H2O

The compound was prepared following the above procedure for [Ca(H2O)5][V(IV)(HIDA)2]·H2O except that HIPDA was used in place of HIDA. Blue crystalline product was obtained from H2O–MeOH-isopropyl alcohol using the slow liquid-diffusion technique at 293 K as reported before.27 This product was stable in the solid state and stored at −20 °C.

[PPh4][V(V)(HIDA)2]·CH2Cl2

[Ca(H2O)5][V(IV)(HIDA)2]·H2O was oxidized in H2O by addition of one equivalent of [NH4]2[Ce(NO3)6] following the reported synthesis.34 The red [V(V)(HIDA)2]− formed in solution was isolated by the addition to the CH2Cl2 solution of two equivalents of PPh4Cl. [PPh4][V(V)(HIDA)2] thus formed was more soluble in the organic layer, which was separated from the aqueous layer using a separatory funnel. Solid product was isolated by evaporating CH2Cl2, and the purity of the material was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy (51V δiso = −263 ppm).34 The 1H NMR spectra and elemental analysis showed that excess PPh4Br was present in this sample. The solid-state NMR spectra were recorded within one month after preparation and before evidence for any sample decomposition.

[PPh4][V(V)(HIPDA)2]·H2O

[PPh4][V(V)(HIPDA)2] was prepared using the procedure reported previously,34 and the purity was determined by NMR spectroscopy.34 This sample contained <5 % of an impurity that formed vanadate in solution, and the rest of the compound had the characteristic triplet–peak pattern with the central peak at 51V δiso=−269 ppm as reported previously for the samples containing [V(V)(HIPDA)2] with different stereoisomers.34,34 The solid-state NMR spectra were recorded within one month after preparation and before evidence for any sample decomposition.

Solid-State NMR spectroscopy

Solid-state 51V NMR spectra were acquired on a Tecmag Discovery spectrometer, interfaced with a wide bore 9.4 T Magnex magnet, and operating at a frequency of 105.23 MHz (9.4T) for 51V. Spectra were also collected on a Varian InfinityPlus spectrometer operating at 157.61 MHz (14.1 T). Vanadium chemical shifts were referenced to neat VOCl3, δiso = 0.0 ppm, used as an external reference.59 This sample was also used to calibrate the 90° pulse widths, which were set to 4.0 µs (γB1/2π ≈ 62 kHz) and 3.2 µs (γB1/2π ≈ 76 kHz) at 9.4 and 14.1 T, respectively. The magic angle was set by maximizing the number of rotational echoes observed in the 23Na NMR free induction decay of solid NaNO3. The angle was set for each sample; accurate setting of the MA is critical when acquiring spectra from the satellite transitions of quadrupolar nuclei over a broad frequency range.60 A 4 mm Doty XC4 MAS probe was used for acquiring all the spectra at 9.4 T while a 3.2 mm Varian T3 MAS probe was used at 14.1 T. The temperature was 20 °C during all experiments and controlled to within +/− 1 degree with a Varian VT controller. For each sample, spectra at several MAS frequencies were acquired. The MAS frequency was controlled by the Tecmag and Varian automated control units to within 5 Hz. All spectra were acquired using a one-pulse experiment with either 1µs or 0.8 µs pulse, a spectral width of 2 MHz, and a recycle delay of 1 s. Proton decoupling did not significantly improve the spectra and was therefore not used. The NMR spectra were processed with Gaussian line broadening functions of 100 Hz, and baseline corrections. Spectra of the entire manifold of central and satellite transitions were simulated with SIMPSON,33 using finite excitation pulses corresponding to the experimental conditions.

Computations

Gaussian0343 was used to calculate the vanadium magnetic shielding and EFG tensors. The b3lyp,43 PBE1PBE,61, 62 and PBEPBE61, 62 functionals were employed; for each method three basis sets were used for all atoms, the 6–311+G(d,p), 6–311++G, and tzvp, as available in the Gaussian package. The coordinates utilized in the calculations were obtained from single-crystal x-ray diffraction data34. Carbon-hydrogen bond lengths were fixed as 1.09 Å in the non-optimized structures. An additional calculation of NMR parameters was performed for both compounds at the b3lyp/6–311+G(d,p) level of theory with geometry-optimized structures at the same level of theory. The NMR parameters for reference VOCl3 were calculated using geometry-optimized structures for each method. The calculated principal components of the magnetic shielding tensor, σii (i = 1, 2, or 3), were converted to the principal components of the chemical shift tensor, δii, using the relation δii = δiso(ref)− δii, where δiso(ref) is the calculated isotropic magnetic shielding of the geometry-optimized reference molecule VOCl3.

Conclusion

We have reported the first 51V solid-state NMR spectra of eight-coordinate non-oxo vanadium complexes. The two complexes, the oxidized forms of amavadin and its analogue, show moderate quadrupolar couplings and chemical shift anisotropies. The isotropic chemicals shifts are less shielded than in the other complexes reported and may reflect the lack of V=O group or the high coordination state. DFT calculations reproduce the experimental EFG parameters well while they reproduce poorly the chemical shifts relating to the oxyamine coordination to the vanadium. The fact that NMR parameters in solution and in the solid state are in close agreement suggests that the unusual coordination environments of these molecules are properly described experimentally. The origin of the discrepancy between theory and experiment for this unusual non-oxo coordination geometry is not understood at this time and needs future exploration. Examination of the available data of solid-state NMR parameters for vanadium(V) complexes of different coordination geometries reveals no simple all-inclusive empirical trends between NMR parameters and coordination number. The overall success of the DFT calculations, however, provides a reliable link between experimental solid-state NMR and structure that makes 51V solid-state NMR a valuable characterization method.

Supplementary Material

BRIEFS.

51V MAS NMR spectroscopy and DFT calculations have been used to study the unusual eight-coordinate non-oxo coordination geometry of oxidized amavadin and its analogues, [PPh4][V(V)(HIDPA)2] and [PPh4][V(V)(HIDA)2]. The computed electric field gradient tensors are in good agreement with the experimental results while chemical shift tensors show some discrepancy with experiment. This work illustrates that unusual coordination geometries can help develop a better understanding of the link between NMR parameters and structure.

Acknowledgments

T.P. acknowledges financial support of the National Science Foundation (CHE-0750079) and the National Institutes of Health (P20-17716, COBRE individual subproject). K.J.O thanks the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada for financial support. D.C.C acknowledges financial support of the Institute of General Medicine at the National Institutes of Health (GM40525) and the National Science Foundation (CHE-0628260 and CHE-0750079).

References

- 1.Crans DC, Smee JJ, Gaidamauskas E, Yang LQ. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:849–902. doi: 10.1021/cr020607t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rehder D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1991;30:148–167. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crans DC, Mahroof-Tahir M, Johnson MD, Wilkins PC, Yang LQ, Robbins K, Johnson A, Alfano JA, Godzala ME, Austin LT, Willsky GR. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2003;356:365–378. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crans DC, Yang LQ, Jakusch T, Kiss T. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:4409–4416. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rehder D. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:957–964. doi: 10.1039/b717565p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertrand D. Bull. Soc. Chim. Biol. 1943;25:194–197. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meisch HU, Reinle W, Schmitt JA. Naturwissenschaften. 1979;66:620–621. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buglyo P, Crans DC, Nagy EM, Lindo RL, Yang LQ, Smee JJ, Jin WZ, Chi LH, Godzala ME, Willsky GR. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:5416–5427. doi: 10.1021/ic048331q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crans DC, Felty RA, Chen HJ, Eckert H, Das N. Inorg. Chem. 1994;33:2427–2438. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckert H, Wachs IE. J. Phys. Chem. 1989;93:6796–6805. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayakawa S, Yoko T, Sakka S. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1993;66:3393–3400. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayakawa S, Yoko T, Sakka S. J. Solid State Chem. 1994;112:329–339. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang WL, Todaro L, Francesconi LC, Polenova T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:5928–5938. doi: 10.1021/ja029246p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang WL, Todaro L, Yap GPA, Beer R, Francesconi LC, Polenova T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:11564–11573. doi: 10.1021/ja0475499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen UG, Jakobsen HJ, Skibsted J. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:2135–2145. doi: 10.1021/ic991243z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nielsen UG, Jakobsen HJ, Skibsted J. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:420–429. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pooransingh N, Pomerantseva E, Ebel M, Jantzen S, Rehder D, Polenova T. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:1256–1266. doi: 10.1021/ic026141e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pooransingh-Margolis N, Renirie R, Hasan Z, Wever R, Vega AJ, Polenova T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:5190–5208. doi: 10.1021/ja060480f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rehder D, Polenova T, Buhl M. Annu. Rep. NMR Spectrosc. 2007;62:50–116. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skibsted J, Jacobsen CJH, Jakobsen HJ. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:3083–3092. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skibsted J, Nielsen NC, Bildsøe H, Jakobsen HJ. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1992;188:405–412. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skibsted J, Nielsen NC, Bildsøe H, Jakobsen HJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:7351–7362. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bolte SE, Ooms KJ, Baruah B, Crans DC, Smee JJ, Polenova T. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;128:052317/052311–052317/052311. doi: 10.1063/1.2830239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ooms KJ, Bolte SE, Smee JJ, Baruah B, Crans DC, Polenova T. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:9285–9293. doi: 10.1021/ic7012667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nica S, Buchholz A, Rudolph M, Schweitzer A, Waechtler M, Breitzke H, Buntkowsky G, Plass W. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2008:2350–2359. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bayer E, Kneifel H. Z .Naturforsch Pt. B. 1972;B 27 207-&. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berry RE, Armstrong EM, Beddoes RL, Collison D, Ertok SN, Helliwell M, Garner CD. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1999;38:795–797. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990315)38:6<795::AID-ANIE795>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reis PM, Silva JAL, da Silva J, Pombeiro AJL. Chem. Commun. 2000:1845–1846. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reis PM, Silva JAL, Palavra AF, da Silva J, Kitamura T, Fujiwara Y, Pombeiro AJL. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2003;42:821–823. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirillova MV, Kuznetsov ML, Da Silva JAL, Da Silva MFC, Da Silva J, Pombeiro AJL. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:1828–1842. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nawi MA, Riechel TL. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1987;136:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geethalakshmi KR, Waller MP, Buhl M. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:11297–11307. doi: 10.1021/ic701650y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bak M, Rasmussen JT, Nielsen NC. J. Magn. Reson. 2000;147:296–330. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armstrong EM, Beddoes RL, Calviou LJ, Charnock JM, Collison D, Ertok N, Naismith JH, Garner CD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:807–808. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lenhardt J, Baruah B, Crans DC, Johnson MD. Chem. Commun. 2006:4641–4643. doi: 10.1039/b610751f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lenhardt JM, Baruah B, Crans DC, Johnson MD. Pure Appl. Chem. 2008 in revision. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramsey NF. Physical Review. 1950;78:699–703. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buhl M. J. Comput. Chem. 1999;20:1254–1261. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buhl M, Hamprecht FA. J. Comput. Chem. 1998;19:113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buhl M, Parrinello M. Chem. Eur. J. 2001;7:4487–4494. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20011015)7:20<4487::aid-chem4487>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buhl M, Schurhammer R, Imhof P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:3310–3320. doi: 10.1021/ja039436f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waller MP, Buhl M, Geethalakshmi KR, Wang D, Walter T. Chem. Eur. J. 2007;13:4723–4732. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frisch MJT, Schlegel GW, Scuseria HB, Robb GE, Cheeseman MA, Montgomery JR, Jr, Vreven JA, Kudin T, Burant KN, Millam JC, Iyengar JM, Tomasi SS, Barone J, Mennucci V, Cossi B, Scalmani M, Rega G, Petersson N, Nakatsuji GA, Hada H, Ehara M, Toyota M, Fukuda K, Hasegawa R, Ishida J, Nakajima M, Honda T, Kitao Y, Nakai O, Klene H, Li M, Knox X, Hratchian JE, Cross HP, Bakken JB, Adamo V, Jaramillo C, Gomperts J, Stratmann R, Yazyev RE, Austin O, Cammi AJ, Pomelli R, Ochterski C, Ayala JW, Morokuma PY, Voth K, Salvador GA, Dannenberg P, Zakrzewski JJ, Dapprich VG, Daniels S, Strain AD, Farkas MC, Malick O, Rabuck DK, Raghavachari AD, Foresman K, Ortiz JB, Cui JV, Baboul Q, Clifford AG, Cioslowski S, Stefanov J, Liu BB, Liashenko G, Piskorz A, Komaromi P, Martin I, Fox RL, Keith DJ, Al-Laham T, Peng MA, Nanayakkara CY, Challacombe A, Gill M, Johnson PMW, Chen B, Wong W, Gonzalez C MW, Pople JA. Wallingford, CT : Gaussian, Inc.; 2004. Editon edn. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mackenzie KJD, Smith ME. Multinuclear Solid-State NMR of Inorganic Materials. Oxford: Pergamon; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clark TM, Grandinetti PJ, Florian P, Stebbins JF. Phys. Rev. B. 2004;70:0642021–0642028. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turner GL, Smith KA, Kirkpatrick RJ, Oldfield E. J. Magn. Reson. 1986;70:408–415. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lapina OB, Mastikhin VM, Shubin AA, Krasilnikov VN, Zamaraev KI. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 1992;24:457–525. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Willans MJ, Feindel KW, Ooms KJ, Wasylishen RE. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;12:159–168. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crans DC, Ehde PM, Shin PK, Pettersson L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:3728–3736. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crans DC, Shin PK. Inorg. Chem. 1988;27:1797–1806. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keramidas AD, Miller SM, Anderson OP, Crans DC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:8901–8915. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Basler W, Lechert H, Paulsen K, Rehder D. J. Magn. Reson. 1981;45:170–172. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mafra L, Almeida Paz FA, Shi F-N, Fernandez C, Trindade T, Klinowski J, Rocha J. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2006;9:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderegg G, Koch E, Bayer E. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1987;127:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Felcman J, Cândida M, Vaz TA, Fraústo Da Silva JJR. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1984;93:101–108. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koch E, Kneifel H, Bayer E. Z. Naturforsch. B. 1986;41b:359–362. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith PD, Harben SM, Beddoes RL, Helliwell M, Collison D, Garner CD. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1997:685–691. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith PD, Berry RE, Harben SM, Beddoes RL, Helliwell M, Collison D, Garner CD. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1997:4509–4516. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harris RK, Becker ED, De Menezes SMC, Goodfellow R, Granger P. Pure Appl. Chem. 2001;73:1795–1818. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shubin AA, Lapina OB, Bondareva VM. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999;302:341–346. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997;78:1396–1396. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.