Abstract

Antiretroviral drug absorption and disposition in cervicovaginal tissue is important for the effectiveness of vaginally or orally administered drug products in preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) of HIV-1 sexual transmission to women. Therefore, it is imperative to understand critical determinants of cervicovaginal tissue pharmacokinetics. This study aimed to examine the mRNA expression and protein localization of three efflux transporters, P-glycoprotein (P-gp), multidrug resistance-associated protein 4 (MRP4), and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP), in the lower genital tract of premenopausal women and pigtailed macaques. Along the human lower genital tract, the three transporters were moderately to highly expressed compared to colorectal tissue and liver, as revealed by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). In a given genital tract segment, the transporter with the highest expression level was either BCRP or P-gp, while MRP4 was always expressed at the lowest level among the three transporters tested. The immunohistochemical staining showed that P-gp and MRP4 were localized in multiple cell types including epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells. BCRP was predominantly localized in the vascular endothelial cells. Differences in transporter mRNA level and localization were observed among endocervix, ectocervix, and vagina. Compared to human tissues, the macaque cervicovaginal tissues displayed comparable expression and localization patterns of the three transporters, although subtle differences were observed between the two species. The role of these cervicovaginal transporters in drug absorption and disposition warrants further studies. The resemblance between human and pigtailed macaque in transporter expression and localization suggests the utility of the macaque model in the studies of human cervicovaginal transporters.

Introduction

Strategies to enhance cervicovaginal tissue drug exposure of topically or orally administered drug products are needed to develop products with greater effectiveness. Topical products (microbicides) and oral products incorporating antiretroviral drugs have been considered for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) of male-to-female sexual transmission of HIV-1.1–4 Some encouraging results have emerged,1,5 however, reproducible and robust success has not been achieved in clinical trials to date.1,5,6 Pharmacokinetic studies have linked the suboptimal outcomes to insufficient drug exposure in the tissues of the lower genital tract.5,7–10 It has been shown that poor adherence is one factor that contributes to the low tissue exposure level achieved in these studies.5,6 Optimal adherence may be difficult to achieve in a large, unconfined population. For this reason, alternative strategies are needed to enhance the absorption and retention of PrEP drugs in the cervicovaginal tissue so that the negative impact of low adherence can be minimized and the “window of forgiveness” for missed doses can be lengthened for once-daily or coitally dependent products. Indeed it has been suggested that the success of the PrEP products rests on the ability to achieve adequate drug exposure in the mucosal tissues, and that one goal of future microbicide trials is to achieve the maximally tolerable drug concentrations in the lower genital tract.5,10

Toward this goal, it is imperative to identify critical determinants that contribute to cervicovaginal tissue drug exposure. The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters play an important role in the pharmacokinetics of many antiretroviral drugs.9,11–15 We have previously examined the mRNA expression of antiretroviral-related efflux and uptake transporters in human cervicovaginal tissue by using conventional reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and found that a number of ABC transporters were highly expressed.16 Among those highly expressed, P-glycoprotein (P-gp), multidrug resistance-associated protein 4 (MRP4), and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) are most relevant to antiretroviral drugs. Their substrates span all classes of antiretroviral drugs used in AIDS treatment and/or microbicide development, such as the entry inhibitor maraviroc, most protease inhibitors, the reverse transcriptase inhibitors tenofovir and zidovudine, and the integrase inhibitor raltegravir.9,11–13,17 It is very possible that these transporters function to limit the cervicovaginal tissue exposure of antiretroviral drugs as they do in other tissues and physiologic barriers such as enterocytes and the blood–brain barrier.18 Further investigation of the feasibility of using transporter inhibitors to increase drug exposure in the cervicovaginal tissue is warranted.

However, functional investigation of cervicovaginal transporters is hampered by a lack of detailed characterization of cervicovaginal transporters in both human and preclinical models used in microbicide testing. The human female lower genital tract is composed of endocervix, ectocervix, and vagina, which are anatomically and physiologically distinct from each other. Different regions of the genital tract have different thicknesses of the protective epithelial layers, and have varying types and amounts of submucosal immune cells. A differential response to the same immunologic stimuli has been reported,19–22 and regionally dependent susceptibility to HIV-1 infection has been suggested among different parts of the lower genital tract. The endocervix as well as the transformation zone between the endocervix and ectocervix were more vulnerable to HIV-1 infection compared to the ectocervix and vagina as examined in a macaque model.3,23 In addition, the replication rate of HIV-1 was shown to be significantly higher in the infected ectocervix compared to the infected vagina, as was demonstrated in a human cervicovaginal tissue explant model.24 Hence, different parts of the female lower genital tract may require different regional levels of drug concentration for successful inhibition of HIV-1 transmission. If this is the case, then regionally specific pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) relationships will be needed for future microbicide development.

Thus, it is necessary to obtain a detailed understanding of the regionally specific transporter expression and localization in the lower genital tract of both human and preclinical models used in microbicide screening. This information is important for delineating the role of transporters in the various regions of the lower genital tract. In addition, this information is critical for further understanding the in vitro–in vivo correlations between the human and preclinical models in microbicide testing, and is helpful in better determining the validity of such models used in the functional study of cervicovaginal transporters. The most widely used model for the screening of PrEP product efficacy and safety is the macaque.25–27 The current study examined the mRNA expression and protein localization of P-gp, MRP4, and BCRP in the endocervix, ectocervix, and vagina of premenopausal women and pigtailed macaques. To our knowledge, this is the first detailed characterization of cervicovaginal transporters that compares humans and macaques. Results from this study will facilitate future evaluation of the functional role of cervicovaginal transporters in tissue drug exposure.

Materials and Methods

Human and pigtailed macaque tissues

All human tissues (endocervix, ectocervix, vagina, sigmoid colon, and liver) were obtained through the Tissue Procurement Facility at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center under IRB approved protocols. The gender and age range of the tissue donors and tissue usage information are summarized in Supplementary Table S1 (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid). Female pigtailed macaque tissues (endocervix, ectocervix, vagina, colorectum, and liver) were obtained from the Washington National Primate Research Center at the University of Washington through the Tissue Distribution Program. The animals were maintained in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The ages of the three macaques used in this study were 12.6, 18.7, and 17.6 years.

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen), and contaminating genomic DNA was eliminated using the Turbo DNase kit (Ambion). All the genital tract tissue samples included epithelial and stromal parts. For the endocervix, ectocervix, and vagina, 100–200 mg of tissue was used for each sample. For liver and colorectal tissue, 50–100 mg of tissue was used for each sample. The cDNA was synthesized using the Superscript III first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed in a CFX Touch 96 instrument (Bio-Rad) using Ssofast Evergreen mastermix (Bio-Rad). The PCR program consisted of an initial denaturation of 95°C×30 s, 40 cycles of 95°C×5 s and 60°C×5 s, followed by a melt curve analysis heating from 65°C to 95°C with 0.5°C increments. The primer sequences for P-gp, BCRP, MRP4, and internal control glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) are listed in Table 1. Primers for human transporters were also used to detect macaque transporters due to the similarity between human and macaque transporter mRNA sequences. The efficiency of PCR reactions was confirmed using the relative standard curve method with serially diluted liver or colon cDNA. The mRNA levels of transporters were normalized to that of GAPDH using the 2-ΔCt method.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences for Detecting P-Glycoprotein, Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 4, Breast Cancer Resistance Protein, and Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase in Human and Macaque Tissues

| Common gene name (official gene symbol) | GenBank accession no. | Primer sequence 5′ to 3′ |

|---|---|---|

| P-gp (ABCB1) | NM_000927 | Forward: CCCATCATTGCAATAGCAGG |

| Reverse: TGTTCAAACTTCTGCTCCTGA | ||

| MRP4 (ABCC4) | NM_005845 | Forward: AAGTGAACAACCTCCAGTTCCAG |

| Reverse: GGCTCTCCAGAGCACCATCT | ||

| BCRP (ABCG2) | NM_004827 | Forward: CAGGTCTGTTGGTCAATCTCACA |

| Reverse: TCCATATCGTGGAATGCTGAAG | ||

| GAPDH | NM_001256799 | Forward: GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT |

| Reverse: GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG |

P-gp, P-glycoprotein; MRP4, multidrug resistance-associated protein 4; BCRP, breast cancer resistance protein; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Immunohistochemical staining

The staining work was conducted by the Research Histology Service of the University of Pittsburgh. Human and macaque tissues (endocervix, ectocervix, vagina, and sigmoid colon/colorectum) were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for over 24 h and embedded in paraffin. Five-micrometer sections were made and deparaffinized using xylene. Antigen retrieval was performed by steaming the slides in the pH 9 retrieval buffer (Dako) for 40 min. The slides were treated with 3% H2O2 for 8 min, followed by blocking in Avidin/Biotin block solution (Vector) for 15 min and blocking in nonserum protein block for 10 min. The following primary antibodies purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. were applied to slides with overnight incubation at 4°C: rabbit anti-human P-gp polyclonal antibody (H-241 clone, 1:15 dilution), mouse anti-human BCRP monoclonal antibody (BXP-21 clone, 1:20 dilution), and mouse anti-human MRP4 monoclonal antibody (F6 clone, 1:50 dilution).

The following secondary antibodies were applied: biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Vector) diluted in goat serum (1:200) was used for P-gp and biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG (Vector) diluted in horse serum (1:200) was used for BCRP and MRP4. After the addition of secondary antibodies, the slides were incubated for 30 min at room temperature. ABC Elite reagents (Vector) were applied afterwards and slides were incubated for 30 min, followed by AEC chromogen (Skytec) incubation for color development. The slides were then counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted with Crystal Mount (Sigma). In the negative control staining for a transporter protein in a given tissue, the nonimmunized IgG purified from the species in which the primary antibody was raised was used instead of the primary antibody.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism software. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc test was used to compare (1) the mRNA level of a given transporter across different tissue types in a species (human or macaque) and (2) different transporters in a given tissue type in a species. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. If two groups were identified to be significantly different, a Student's t-test would be conducted to obtain the exact p values.

Results

mRNA level of P-gp, MRP4, and BCRP in human and macaque cervicovaginal tissues

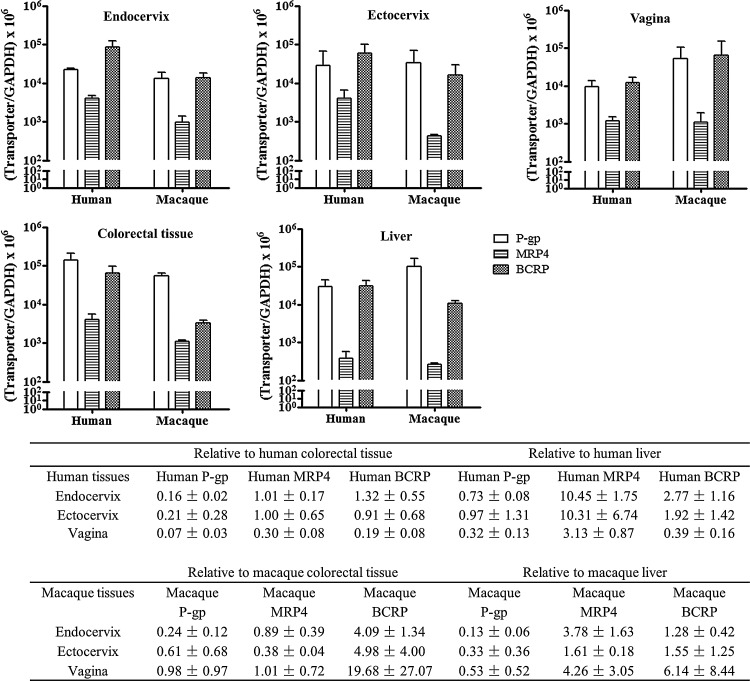

The general tendency of transporter expression found in the human lower genital tract was that P-gp, MRP4, and BCRP were moderately to highly expressed compared to the positive controls (colorectal tissue and liver) in both human and macaque tissues (Fig. 1). With respect to the GAPDH-normalized mRNA levels, either P-gp or BCRP appeared to be the highest in a given human or macaque genital tract tissue, while MRP4 always appeared to be the lowest. In human endocervix, the BCRP level was significantly higher than the P-gp (p=0.012) and MRP4 (p=0.004) levels. In human ectocervix, the BCRP level was significantly higher than the MRP4 level (p=0.012). In human vagina, P-gp (p=0.002) and BCRP levels (p=0.001) were significantly higher than the MRP4 level, while no difference between P-gp and BCRP was observed in human vagina. In macaque genital tract tissues, no significant difference was observed among the three transporters (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

mRNA expression of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) (□), multidrug resistance-associated protein 4 (MRP4) (▤), and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) ( ) in human and macaque cervicovaginal tissues. The expression in endocervix, ectocervix, vagina, sigmoid colon/colorectum, and liver was examined in tissues from four to six human subjects or three macaques. The table summarizes the transporter expression levels in genital tract tissues relative to the expression levels in colorectal tissue or liver. Each sample was measured once in triplicate, and the average value was used to reflect the expression level in this sample. The data shown represent the mean±standard deviation of all samples in a given group.

) in human and macaque cervicovaginal tissues. The expression in endocervix, ectocervix, vagina, sigmoid colon/colorectum, and liver was examined in tissues from four to six human subjects or three macaques. The table summarizes the transporter expression levels in genital tract tissues relative to the expression levels in colorectal tissue or liver. Each sample was measured once in triplicate, and the average value was used to reflect the expression level in this sample. The data shown represent the mean±standard deviation of all samples in a given group.

Further statistical analyses were conducted to compare the expression of each transporter across different tissues. In humans, each of the genital tract tissues (endocervix, ectocervix, and vagina) displayed a several fold lower (statistically significant) expression level in P-gp compared to the sigmoid colon, but there was no difference between genital tract tissues and liver in P-gp expression (Fig. 1). Within the genital tract, human P-gp expression was highest in the ectocervix, followed by the endocervix and vagina, but there was no significant difference among these three tissue types (Fig. 1). For MRP4, there were significant differences between the human endocervix (p<0.001) and liver and between the ectocervix (p=0.007) and liver, but no difference existed between the genital tract and colon (Fig. 1). Within the genital tract, human MRP4 expressions in the endocervix and ectocervix were similar, while the vaginal MRP4 level was significantly lower than the endocervical level (p<0.001) (Fig. 1). For BCRP, there was no difference between genital tract tissues and controls. Within the genital tract, human BCRP expression was highest in the endocervix, followed by the ectocervix and vagina, and there was a significant difference between the endocervix and vagina (p=0.002) (Fig. 1). In macaques, the three transporters were also moderately to highly expressed in the endocervix, ectocervix, and vagina, compared to macaque liver and colorectum. For each of the three transporters examined in macaque, there was no significant difference in transporter mRNA level among the endocervix, ectocervix, and vagina, nor was there any difference between genital tract tissues and positive control tissues (colorectum and liver) (Fig. 1).

The transporter expression levels in female genital tract relative to colorectal or liver levels are summarized in the table anchored to Fig. 1. Compared to humans, the macaque P-gp level in the vagina and BCRP level in the vagina were much higher than those levels in corresponding human tissues, but significant differences were not found due to the high variability among different macaques.

Overall, P-gp, MRP4, and BCRP were moderately to highly expressed at the mRNA level in the lower genital tract tissues of humans and macaques compared to the positive control tissues. The cervicovaginal expression patterns of the three transporters were generally comparable between human and macaque.

Protein localization of P-gp, MRP4, and BCRP in human and macaque cervicovaginal tissues

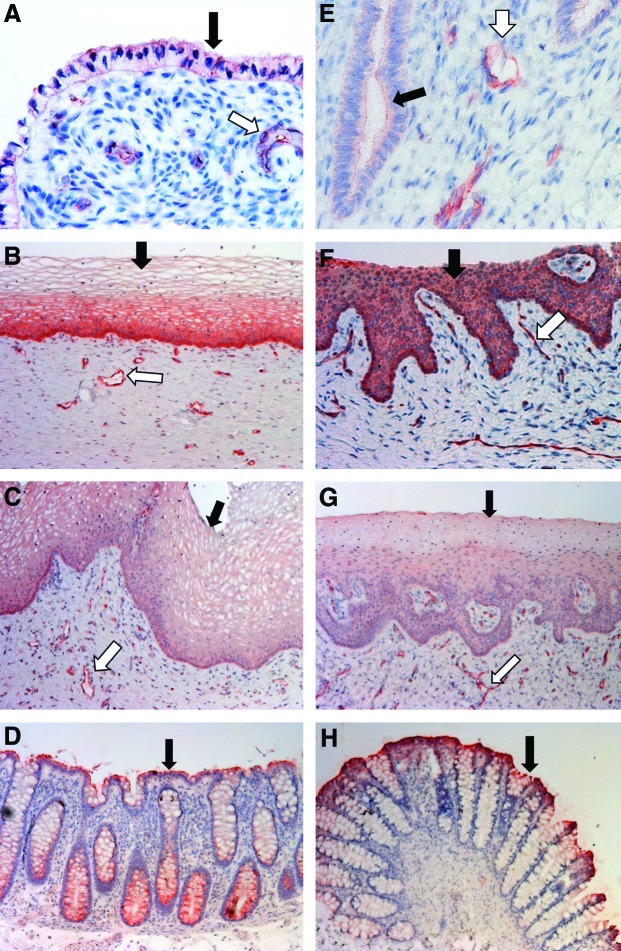

For P-gp staining in human tissues, the apical membrane of the columnar epithelial cells of the sigmoid colon (positive control) was stained strongly positive, while the colonic vascular endothelial cells were not stained (Fig. 2D). In the endocervix, ectocervix, and vagina, the epithelial cells facing the cervicovaginal lumen as well as the endothelial cells of the blood and lymphatic vessels running through the stromal tissue were stained positive (Fig. 2A–C). Among the epithelial cells of the three kinds of genital tract tissues, the stratified squamous epithelial cells in ectocervical tissue showed most intensive staining (Fig. 2B). In ectocervix, the basal layer of the ectocervical epithelium, which is composed of a single layer of columnar cells, showed even more intense staining compared to the uppermost layers (Fig. 2B). Notably, the uppermost layers predominantly displayed plasma membrane staining for P-gp, while the basal layer of the epithelium displayed cytosol staining (Fig. 2B). This difference was possibly due to a more abundant P-gp distribution in subcellular organelles in the basal layer epithelial cells as reported in other cell types.28,29 The staining of the endocervical and vaginal epithelial cells appeared to be weaker than that of the ectocervical epithelial cells (Fig. 2C). In addition, the difference in staining signal intensity between the uppermost and basal epithelial layers in human vagina was less evident than the difference observed in the ectocervix (Fig. 2C). However, the staining of the stromal vascular endothelial cells in human endocervix and vagina was as strong as it was in the ectocervix.

FIG. 2.

Localization of P-gp protein in human and macaque cervicovaginal tissues. (A–D) Endocervix, ectocervix, vagina, and sigmoid colon of women. (E–H) Endocervix, ectocervix, vagina, and colorectum of pigtailed macaques. Black arrows: epithelial cells; white arrows: vascular endothelial cells. Magnification: 40×for (A) and (E), 10×for (B, C, D, F, G, H). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid

The positive staining of P-gp in the human lower genital tract and colorectal tissue corresponded to their moderate to high level mRNA expression (Fig. 1). For P-gp staining in macaque tissues, the staining patterns were generally similar to those of human tissues (Fig. 2E–H). However, differences had been observed between the two species. In the epithelial cells of the macaque ectocervix and vagina, the staining signal was found in the cytoplasm rather than preferentially distributed on the plasma membrane (Fig. 2F and G). Moreover, there was no clear difference in signal intensity between different layers of the epithelium in the macaque ectocervix and vagina. The similarity between human and macaque in P-gp staining was consistent with the similarity in mRNA expression between these two species. The staining results for human and macaque P-gp are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the Immunohistochemical Staining Results of P-Glycoprotein, Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 4, and Breast Cancer Resistance Protein in Human and Macaque Tissues

| P-gp | MRP4 | BCRP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue type | Cell type | Human | Macaque | Human | Macaque | Human | Macaque |

| Endocervix | Columnar epithelial cells | ● | ● | ●● | ●● | ◯ | ◯ |

| Vascular endothelial cells | ●● | ●● | ◯ | ◯ | ●● | ●● | |

| Ectocervix | Squamous epithelial cells | ●● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ◯ |

| Vascular endothelial cells | ●● | ●● | ● | ● | ●● | ●● | |

| Vagina | Squamous epithelial cells | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ◯ |

| Vascular endothelial cells | ●● | ●● | ● | ● | ●● | ●● | |

| Sigmoid colon (human) or colorectum (macaque) | Columnar epithelial cells | ●● | ●● | ● | ● | ●● | ● |

| Vascular endothelial cells | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ● | ◯ | ● | |

◯, not detected; ●, positively stained; ●●, strongly positive.

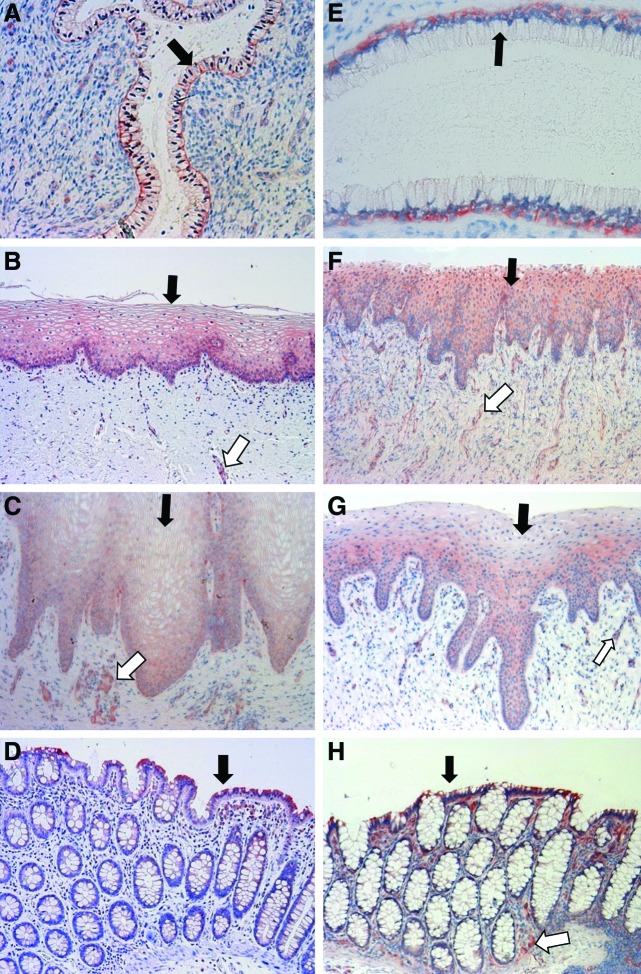

For MRP4 staining in human tissues, the columnar epithelial cells of the colorectum gave a moderately positive signal, while no staining was found in the vascular endothelial cells of the colon tissue (Fig. 3D). Among genital tract tissues, the most intense staining was observed on the basolateral membrane of the columnar epithelial cells in the endocervix. However, no staining signal can be readily observed in the vascular endothelial cells of the endocervix (Fig. 3A). Compared to the endocervix, the staining of ectocervical and vaginal epithelial cells appeared to be weaker. The staining of vascular endothelial cells in the ectocervix and vagina appeared to be more obvious than that in the endocervix (Fig. 3A–C). For MRP4 staining in macaque tissues, the staining of the columnar epithelial cells in the macaque colorectum appeared to be less evident, while the vascular endothelial cells displayed stronger staining compared to those cells in the human sigmoid colon (Fig. 3D and H). In the macaque endocervix, the staining pattern was identical to that of the human endocervix (Fig. 3E).

FIG. 3.

Localization of MRP4 protein in human and macaque cervicovaginal tissues. (A–D) Endocervix, ectocervix, vagina, and sigmoid colon of women. (E–H) Endocervix, ectocervix, vagina, and colorectum of pigtailed macaques. Black arrows: epithelial cells; white arrows: vascular endothelial cells. Magnification: 20×for (A), 40×for (E), 10×for (B, C, D, F, G, H). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid

In the macaque ectocervix and vagina, the cytoplasmic staining was the major staining pattern for MRP4, and no positive staining on the plasma membrane could be observed (Fig. 3F and G). In the human ectocervix, vagina, and colorectum, the MRP4 staining appeared weaker than the signal of P-gp (Figs. 2 and 3), which was in line with the lower mRNA level of MRP4 in these tissues. The stronger MRP4 staining signal in the human endocervix and ectocervix compared to the vagina was consistent with several fold higher MRP4 mRNA levels in the endocervix and ectocervix (Fig. 1). In addition, the similarity between human and macaque in MRP4 staining corresponded to the similarity in mRNA levels (Fig. 1). The staining results for human and macaque MRP4 are summarized in Table 2.

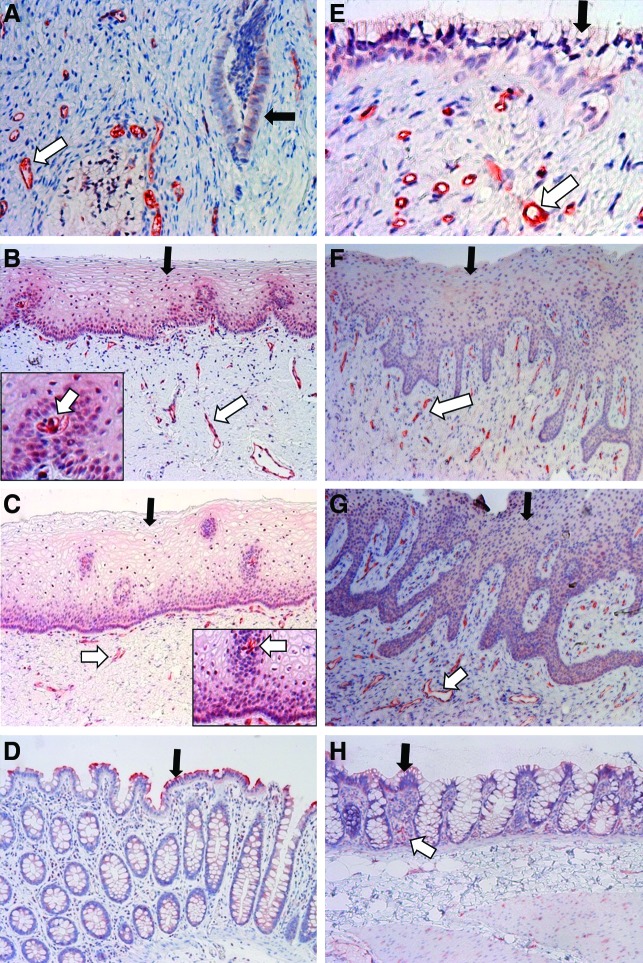

For BCRP staining in human tissues, the epithelial cells of the human sigmoid colon exhibited a strong positive signal, while the staining of vascular endothelial cells was not observed in the colon (Fig. 4D). For the genital tract tissues, the staining was not observed in the plasma membrane of epithelial cells. However, a positive staining signal was found in the nucleus of a subset of ectocervical and vaginal epithelial cells (Fig. 4B and C). Intense staining was observed for the vascular endothelial cells within the stromal tissue of the endocervix, ectocervix, and vagina (Fig. 4A–C). Notably, strongly positive staining of blood vessels running through the epithelial layers of human ectocervix and vagina could be observed (Fig. 4B and C), which clearly distinguished these vessels from surrounding epithelial cells. For BCRP staining in macaque tissues, the staining patterns were generally similar to those of human tissues (Fig. 4E–H). However, differences were observed between the two species. The nucleus staining was not observed in the epithelial cells of the macaque ectocervix and vagina (Fig. 4F and G). In addition, the epithelial cells of the macaque colorectum appeared to have weaker staining compared to their human counterparts, while the staining of vascular endothelial cells was more obvious compared to those cells in the human colon (Fig. 4D and H). The strong staining signal of BCRP in the human and macaque genital tract tissues was in line with the high mRNA level of BCRP in these tissues. The staining results for human and macaque BCRP are summarized in Table 2.

FIG. 4.

Localization of BCRP protein in human and macaque cervicovaginal tissues. (A–D) Endocervix, ectocervix, vagina, and sigmoid colon of women. (E–H) Endocervix, ectocervix, vagina, and colorectum of pigtailed macaques. The insets of (B) and (C) are enlarged epithelial areas that contain intensely stained intraepithelial blood vessels and the positively stained epithelial nuclei. Black arrows: epithelial cells; white arrows: vascular endothelial cells. Magnification: 40×for (A) and (E), 10×for (B, C, D, F, G, H). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid

Discussion

The observed patterns of mRNA expression and protein localization of the three transporters in human sigmoid colon and liver, which were used as positive control tissues in our study, were consistent with the studies published by other groups.30–35 With respect to the transporters in the human female genital tract, we validated the findings on cervical tissue P-gp and BCRP, which were previously reported by other researchers and our group.16,35,36 Furthermore, we extended the characterization of these two transporters to the human vagina. To our knowledge, this study is the first to characterize MRP4 protein localization in the human lower genital tract. In addition, this is the first characterization of efflux transporters in the cervicovaginal and colorectal tissues of the pigtailed macaque, which is a widely used model for microbicide testing.25–27

There has been an urgent need to identify critical determinants of cervicovaginal tissue drug PK/PD to optimize PrEP strategies.6,16,37 Efflux transporters and uptake transporters have been reported to pump out or influx many antiretroviral drugs.9,38,39 In addition, cytochrome P450 (CYP) metabolizing enzymes play a role in the metabolic activation or inactivation of these drugs.40 If these transporters and CYP enzymes are present and functional in the cervicovaginal tissues, they will likely affect the distribution of topically or orally administered drugs to the sites of HIV-1 transmission. Our previous study has examined the mRNA expression of transporters and enzymes in the human lower genital tract (ectocervix and vagina) using conventional RT-PCR.16 Although a number of efflux transporters (P-gp, BCRP, MRP4, MRP5, and MRP7) were found to be expressed at moderate to high levels compared to liver, only a limited number of uptake transporters, such as OCT2 and ENT1 was found to be positively expressed in both the epithelium and stroma of the ectocervix and vagina.16 OAT1 and OAT3, the major uptake transporters for tenofovir, were not detectable by RT-PCR in these tissues.16 The majority of CYP isoforms, such as CYP3A4, were not detectable or were expressed at much lower levels compared to the liver.16 The relatively high mRNA levels of efflux transporters suggest that they may be more important regulators than uptake transporters or CYP enzymes in drug exposure in the cervicovaginal tissues.

In addition to relatively high expression levels, extensive studies have tested the feasibility of inhibiting efflux transporters to increase drug exposure in tissues.9,18,41–43 The most frequently tested approach is coadministration of transporter inhibitors.42,43 Another promising approach is to encapsulate the drug into lipid nanoparticles so that the drug will enter the cell via alternative routes and the transporter efflux could be minimized.42 Compared to efflux transporters, there is much less information on the strategies available to enhance the uptake transporter function and get more drug molecules into the cell. Therefore, the relatively high expression levels of P-gp, MRP4, and BCRP in cervicovaginal tissues, the high relevance of these transporters to antiretroviral drugs, and the availability of multiple approaches to overcome the efflux activity led us to focus on the three efflux transporters in follow-up studies.

The cervicovaginal pharmacokinetics of many antiretroviral drugs may be affected by P-gp, MRP4, and BCRP, given their expression and localization in the female genital tract. Tenofovir and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) are undergoing active development toward drug products used in topical or oral PrEP. They can be effluxed by MRP4 and P-gp, respectively.9,11,18 The entry inhibitor maraviroc is a P-gp substrate and is undergoing development in combination with dapivirine or tenofovir toward a combination microbicide (http://www.ipmglobal.org/our-work/ipm-product-pipeline/maraviroc).12 In addition to transporting the aforementioned drugs used for HIV prevention, P-gp, MRP4, and BCRP also transport drugs that are frequently used in highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) against acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). All protease inhibitors and integrase inhibitors are P-gp substrates, and some nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors, including lamivudine, didanosine, stavudine, and zidovudine, are BCRP substrates.9 The transporters present in the female genital tract may affect the drug concentration in these tissue compartments, and may alter drug efficacy and the amount of infective viral particles in cervicovaginal tissues and fluids. This may, in turn, impact the rate of HIV sexual transmission from females to males. Overall, the transporters examined in this study may affect the pharmacokinetics and effectiveness of many drugs used in HIV prevention and/or AIDS treatment.

Because P-gp and MRP4 transporters appeared to be expressed at different levels along the female genital tract, it is possible that they will affect drug pharmacokinetics in a region-specific manner. For example, the MRP4 protein is localized with higher density in the endocervical epithelial cells compared to the ectocervix and vagina. Even if the same tenofovir dose is administered to the patient intravaginally or orally, different segments of the female genital tract may have differential exposure due to differential efflux activities. A detailed pharmacokinetic analysis during the conduction of preclinical and clinical PrEP studies appears necessary to examine whether the transporter activity significantly reduces the drug concentration in certain areas of the genital tract under certain conditions. Should this occur, a dose adjustment might be necessary, not to achieve the same drug level along the genital tract, but to ensure that the drug concentration in each part of the genital tract is above the effective concentration required for efficacy.

It should be noted that all the possible effects of cervicovaginal transporters are based on the assumption that a positive mRNA and protein expression correlate with efflux activity and a significant role in drug pharmacokinetics. However, there are a number of reasons as to why the transporter activity is not observed in pharmacokinetic analysis despite a high expression level. First, posttranslational modifications of transporter proteins have been reported for some types of tissues and cells.44,45 These modifications can be critical to transporter activity and are tissue dependent. Therefore, positive expression does not necessarily predict transport activity, and the difference in mRNA expression levels between different tissues does not necessarily result in functionally different outcomes in efflux activity.

Even if the positively expressed transporters possess activity, they do not necessarily exert a significant impact on the pharmacokinetics of every substrate. First, the drug entry and retention in a given tissue site are determined by multiple factors, including the drug's passive transcellular and paracellular permeability. A transporter substrate with high passive permeability may be less affected by transporter-mediated active efflux compared to substrates with lower passive permeability. In addition, efflux transporters can be saturated when the substrate concentration is high,18 and the transporter effect may not be seen in this scenario. Therefore, transporters may play a role under certain conditions, e.g., when the tissue drug concentration drops below the saturation level. Furthermore, very few transporters may in fact be enough to efflux most drug molecules depending on their activity and/or capacity. Therefore, the differential expression/localization of a given transporter in different tissues will not necessarily translate to functionally different outcomes in efflux of a substrate, because multiple other transporters may have the same expression pattern and the overall efflux activity for this substrate remains the same across tissues. Functional studies are needed to characterize the influence of cervicovaginal transporters on a series of commonly used antiretroviral drugs under conditions relevant to PrEP drug use.

The region-specific mRNA and protein characterization reported in this study could help rationalize future functional studies. The transporters examined in this study are localized in multiple cell types, including columnar (glandular) epithelial cells, squamous epithelial cells, and vascular endothelial cells. The tissue-associated immune cells are also presumably positive in transporter expression, because the immune cells purified from blood demonstrated positive expression and activity of multiple transporters.9,44 This suggested that each transporter may affect various aspects of substrate absorption and disposition. For topically (vaginally) administered drugs, the efflux transporters located on the luminal (columnar and squamous) epithelial cells provide a mechanism that can directly limit drug penetration into tissue, which could be similar to that observed for the enterocytes lining the small intestine.9 As the columnar (glandular) epithelial cells are responsible for the secretion of mucosal fluid, the transporters located in this type of cell likely will affect the secretion of absorbed drugs from tissue to the mucosal fluid. The transporters located on the venous/lymphatic endothelium may have a role in the blood/lymphatic drainage from tissue to systemic blood/lymph circulation. For the orally administered drugs, the transporters on the venous/lymphatic endothelium may limit the distribution from blood/lymph to cervicovaginal tissues, and the transporters on glandular epithelial cells may function to efflux the drug from tissue to lumen.

Thus, to study a transporter's role in PrEP, it is critical to understand its comprehensive role in controlling drug exposure in the entire tissue and not just its function in a specific type of cell. When utilizing in vitro models to study transporter function, it appears necessary to employ multiple cell lines corresponding to the multiple cell types that carry transporter protein in the female genital tract. When utilizing animal models for functional characterization, it is prudent to ensure that the animal's genital tract has different regions anatomically similar to human tissues and that patterns of transporter expression and localization are comparable to those patterns in humans. In this study, the pigtailed macaque showed expression and localization patterns of cervicovaginal P-gp, MRP4, and BCRP comparable to humans. In addition, the macaque is considered to be a biologically relevant model for PrEP efficacy assessment.25–27 Therefore, with the utilization of the macaque model, the overall impact of transporters on the pharmacokinetics and efficacy of PrEP drugs can be evaluated in the same model. These attributes suggest that the macaque is a good model to study the functionality of cervicovaginal transporters. The similarity in transporter expression between humans and macaques also confirmed the utility of macaques in microbicide safety and efficacy testing, especially when the three efflux transporters will affect the absorption and disposition of the tested drug.

A detailed functional characterization of efflux transporters in the cervicovaginal tissues will facilitate PrEP optimization in multiple aspects. First, this information is useful for the optimization of PrEP drug candidates and formulations. If the transporters play a significant role in drug distribution into the cervicovaginal tissues, then nonsubstrate drugs may be better candidates than transporter substrates, if all other attributes are similar. Alternatively, the substrates could be chemically modified to remove transporter binding moieties while at the same time retain antiviral activity. Some antiretroviral drugs, such as protease inhibitors, are potent inhibitors of efflux transporters through competitive binding.9 Some pharmaceutical excipients, such as pluronic P85, inhibit transporter efflux by temporarily inhibiting intracellular ATPase activity and/or modulating cell membrane fluidity.43 It has been reported that nanosized drug delivery systems could fuse with the cell membrane and release the encapsulated drug molecules within the cells. Encapsulating drugs into such delivery systems could circumvent the direct contact of these drugs with the membrane-bound efflux transporters.42 The utilization of these strategies to overcome transporter efflux may increase drug exposure and efficacy in HIV prevention if the transporters' role is significant. In addition, the information on cervicovaginal transporter function will help explain and predict transporter-mediated drug–drug interaction and interindividual variability in antiretroviral pharmacokinetics and efficacy in the female genital tract.38 The genotyping of the transporter coding sequence may help predict the transporter activity in each patient and enable the individualized dosing of PrEP drug products.

Collectively, this study has provided detailed characterization of the mRNA expression and protein localization of the three most relevant efflux transporters in the lower genital tract of humans and pigtailed macaque. The information obtained from the current study will facilitate further investigations of the role of transporters in drug pharmacokinetics in the female lower genital tract. The results from future transporter functionality studies will, in turn, accelerate the development of novel approaches, which could improve the local pharmacokinetics and efficacy of microbicides and other drugs that are intended for the female lower genital tract.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Drs. Dorothy Patton, Pamela Moalli, and Raman Venkataramanan for their assistance with tissue acquisition. We would also like to thank Drs. Ian McGowan and Charlene Dezzutti for their help with instrument use. In addition, we acknowledge Ms. Yvonne Cosgrove Sweeney for the critical review of this article. The Tissue Distribution Program was supported by the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (ORIP) of the National Institutes of Health under grant P51OD010425. Other research work reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award AI082639. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, et al. : Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science 2010;329(5996):1168–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramjee G: Microbicide research: Current and future directions. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010;5(4):316–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haase AT: Targeting early infection to prevent HIV-1 mucosal transmission. Nature 2010;464(7286):217–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutler B. and Justman J: Vaginal microbicides and the prevention of HIV transmission. Lancet Infect Dis 2008;8(11):685–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams JL. and Kashuba AD: Formulation, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of topical microbicides. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2012;26(4):451–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romano J, Kashuba A, Becker S, Cummins J, Turpin J, and Veronese Fon behalf of the Antiretroviral Pharmacology in HIV Prevention Think Tank Participants: Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics in HIV Prevention; Current Status and Future Directions: A Summary of the DAIDS and BMGF Sponsored Think Tank on Pharmacokinetics (PK)/Pharmacodynamics (PD) in HIV Prevention. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2013;29(11):1418–1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor S. and Davies S: Antiretroviral drug concentrations in the male and female genital tract: Implications for the sexual transmission of HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010;5(4):335–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dumond JB, Yeh RF, Patterson KB, et al. : Antiretroviral drug exposure in the female genital tract: Implications for oral pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis. AIDS 2007;21(14):1899–1907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kis O, Robillard K, Chan GN, and Bendayan R: The complexities of antiretroviral drug-drug interactions: Role of ABC and SLC transporters. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2010;31(1):22–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karim SS, Kashuba AD, Werner L, and Karim QA: Drug concentrations after topical and oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis: Implications for HIV prevention in women. Lancet 2011;378(9787):279–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imaoka T, Kusuhara H, Adachi M, Schuetz JD, Takeuchi K, and Sugiyama Y: Functional involvement of multidrug resistance-associated protein 4 (MRP4/ABCC4) in the renal elimination of the antiviral drugs adefovir and tenofovir. Mol Pharmacol 2007;71(2):619–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abel S, Back DJ, and Vourvahis M: Maraviroc: Pharmacokinetics and drug interactions. Antivir Ther 2009;14(5):607–618 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Transporter Consortium Giacomini KM, Huang SM, et al. : Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010;9(3):215–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuetz JD, Connelly MC, Sun D, et al. : MRP4: A previously unidentified factor in resistance to nucleoside-based antiviral drugs. Nat Med 1999;5(9):1048–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuda Y, Takenaka K, Sparreboom A, et al. : Human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors interact with ATP binding cassette transporter 4/multidrug resistance protein 4: A basis for unanticipated enhanced cytotoxicity. Mol Pharmacol 2013;84(3):361–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou T, Hu M, Cost M, Poloyac S, and Rohan L: Expression of transporters and metabolizing enzymes in the female lower genital tract: Implications for microbicide research. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2013;29(11):1496–1503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez-Novoa S, Labarga P, Soriano V, et al. : Predictors of kidney tubular dysfunction in HIV-infected patients treated with tenofovir: A pharmacogenetic study. Clin Infect Dis 2009;48(11):e108–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giacomini KM, Huang SM, Tweedie DJ, et al. : Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010;9(3):215–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Africander D, Louw R, Verhoog N, Noeth D, and Hapgood JP: Differential regulation of endogenous pro-inflammatory cytokine genes by medroxyprogesterone acetate and norethisterone acetate in cell lines of the female genital tract. Contraception 2011;84(4):423–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharkey DJ, Macpherson AM, Tremellen KP, and Robertson SA: Seminal plasma differentially regulates inflammatory cytokine gene expression in human cervical and vaginal epithelial cells. Mol Hum Reprod 2007;13(7):491–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGowin CL, Popov VL, and Pyles RB: Intracellular Mycoplasma genitalium infection of human vaginal and cervical epithelial cells elicits distinct patterns of inflammatory cytokine secretion and provides a possible survival niche against macrophage-mediated killing. BMC Microbiol 2009;9:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burgener A, Tjernlund A, Kaldensjo T, et al. : A systems biology examination of the human female genital tract shows compartmentalization of immune factor expression. J Virol 2013;87(9):5141–5150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Q, Estes JD, Schlievert PM, et al. : Glycerol monolaurate prevents mucosal SIV transmission. Nature 2009;458(7241):1034–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dezzutti CS, Uranker K, Bunge KE, et al. : HIV-1 infection of female genital tract tissue for use in prevention studies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;63(5):548–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veazey RS, Shattock RJ, Klasse PJ, and Moore JP: Animal models for microbicide studies. Curr HIV Res 2012;10(1):79–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patton DL, Sweeney YT, and Paul KJ: A summary of preclinical topical microbicide rectal safety and efficacy evaluations in a pigtailed macaque model. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36(6):350–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patton DL, Cosgrove Sweeney YT, and Paul KJ: A summary of preclinical topical microbicide vaginal safety and chlamydial efficacy evaluations in a pigtailed macaque model. Sex Transm Dis 2008;35(10):889–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solazzo M, Fantappie O, Lasagna N, et al. : P-gp localization in mitochondria and its functional characterization in multiple drug-resistant cell lines. Exp Cell Res 2006;312(20):4070–4078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munteanu E, Verdier M, Grandjean-Forestier F, et al. : Mitochondrial localization and activity of P-glycoprotein in doxorubicin-resistant K562 cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2006;71(8):1162–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ufer M, Hasler R, Jacobs G, et al. : Decreased sigmoidal ABCB1 (P-glycoprotein) expression in ulcerative colitis is associated with disease activity. Pharmacogenomics 2009;10(12):1941–1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bleasby K, Castle JC, Roberts CJ, et al. : Expression profiles of 50 xenobiotic transporter genes in humans and pre-clinical species: A resource for investigations into drug disposition. Xenobiotica 2006;36(10–11):963–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Englund G, Rorsman F, Ronnblom A, et al. : Regional levels of drug transporters along the human intestinal tract: Co-expression of ABC and SLC transporters and comparison with Caco-2 cells. Eur J Pharm Sci 2006;29(3–4):269–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hilgendorf C, Ahlin G, Seithel A, et al. : Expression of thirty-six drug transporter genes in human intestine, liver, kidney, and organotypic cell lines. Drug Metab Dispos 2007;35(8):1333–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta N, Martin PM, Miyauchi S, et al. : Down-regulation of BCRP/ABCG2 in colorectal and cervical cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006;343(2):571–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maliepaard M, Scheffer GL, Faneyte IF, et al. : Subcellular localization and distribution of the breast cancer resistance protein transporter in normal human tissues. Cancer Res 2001;61(8):3458–3464 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider J, Efferth T, Mattern J, Rodriguez-Escudero FJ, and Volm M: Immunohistochemical detection of the multi-drug-resistance marker P-glycoprotein in uterine cervical carcinomas and normal cervical tissue. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;166(3):825–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson CG, Cohen MS, and Kashuba AD: Antiretroviral pharmacology in mucosal tissues. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;63(Suppl 2):S240–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiser JJ, Aquilante CL, Anderson PL, et al. : Clinical and genetic determinants of intracellular tenofovir diphosphate concentrations in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;47(3):298–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Minuesa G, Huber-Ruano I, Pastor-Anglada M, et al. : Drug uptake transporters in antiretroviral therapy. Pharmacol Ther 2011;132(3):268–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rathbun RC. and Liedtke MD: Antiretroviral drug interactions: Overview of interactions involving new and investigational agents and the role of therapeutic drug monitoring for management. Pharmaceutics 2011;3(4):745–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marquez B. and Van Bambeke F: ABC multidrug transporters: Target for modulation of drug pharmacokinetics and drug-drug interactions. Curr Drug Targets 2011;12(5):600–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nieto Montesinos R, Beduneau A, Pellequer Y, and Lamprecht A: Delivery of P-glycoprotein substrates using chemosensitizers and nanotechnology for selective and efficient therapeutic outcomes. J Control Release 2012;161(1):50–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goole J, Lindley DJ, Roth W, et al. : The effects of excipients on transporter mediated absorption. Int J Pharm 2010;393(1–2):17–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Giraud C, Manceau S, and Treluyer JM: ABC transporters in human lymphocytes: Expression, activity and role, modulating factors and consequences for antiretroviral therapies. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2010;6(5):571–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stolarczyk EI, Reiling CJ, and Paumi CM: Regulation of ABC transporter function via phosphorylation by protein kinases. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2011;12(4):621–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.