Introduction

Much has been written about the scope of pharmacy practice in Canada over the past decade. The benefits of pharmacists to the primary care team, in terms of both cost and patient health, are well documented, as are the reasons why community pharmacists have yet to widely adopt this new role.1-3 Barriers commonly reported by pharmacists generally involve issues of time, money, training and lack of support from patients and other health care professionals.4-6 Despite these self-perceived barriers, expectations of pharmacists continue to increase, as do support and funding, particularly in Alberta.

Alberta, a worldwide leader in pharmacy practice, has given pharmacists one of the largest scopes of practice and amount of financial support in the world. Despite this, uptake of pharmacy services remains largely superficial. Pharmacists in Alberta are able to prescribe and adapt medications, administer medications by injection and develop patient care plans, but they average fewer than 2 of these services per pharmacy per day.7-9

The continued support for pharmacy services in Alberta brings into question whether the aforementioned barriers are the only issues holding back pharmacists. Indeed, evidence suggests that removing self-reported barriers is not sufficient to promote practice change.5 Rosenthal et al.10 provided a unique explanation of this poor uptake of clinical services. These authors hypothesized that pharmacists themselves are holding back practice change by undervaluing their own training and being unable to apply their knowledge in the novel ways expected from a primary care clinician. I believe that the ideas suggested by Rosenthal et al. are likely a major contributor to the lack of uptake of practice change, but I also believe that the issue comes back to a more basic problem: Many pharmacists do not perceive the necessity of change.

The process of change

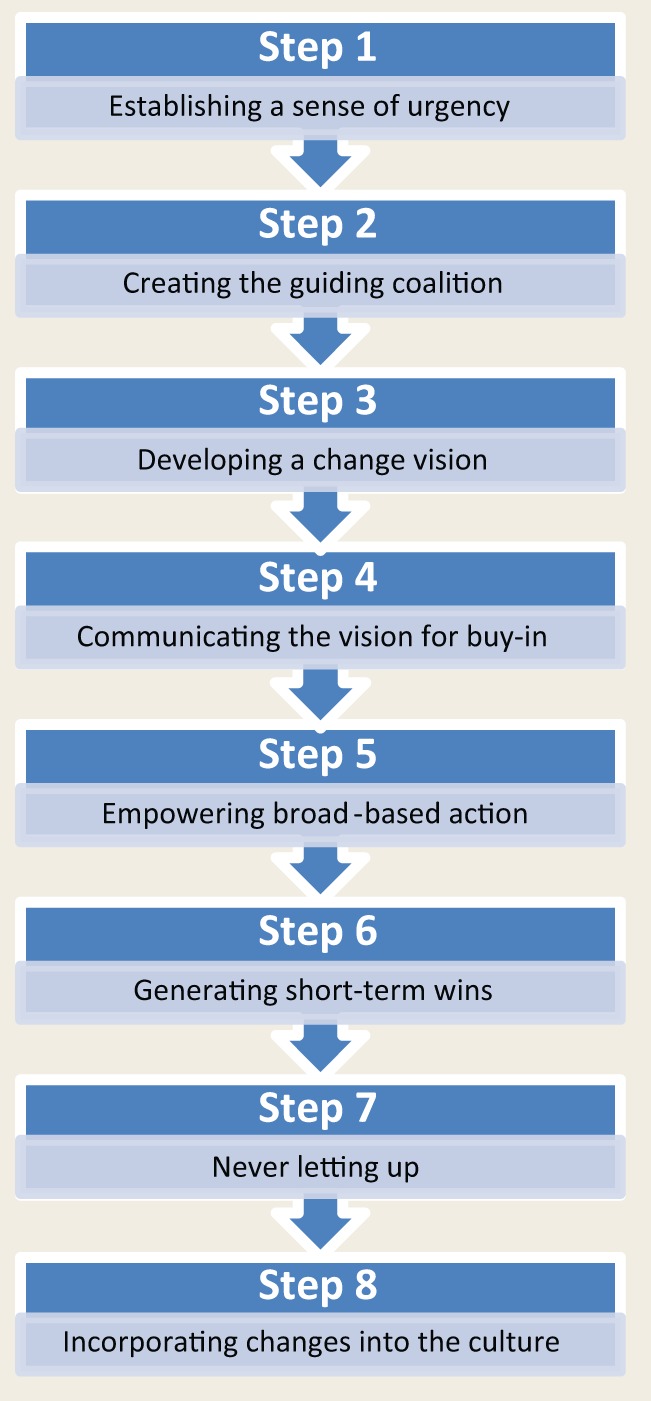

The changes being implemented in pharmacy are similar to those seen in any major organization. As such, one would anticipate the success of change to depend on similar factors. Kotter’s11 8-Step Process for Leading Change gives insight into how successful practice change may occur (Figure 1).12 Of key importance is “establishing a sense of urgency.” Without the perceived need for change, individuals will not make the efforts that are required for change to be successful. I propose that many pharmacists themselves do not see the need to change because they already view themselves as patient-focused and essential to the health care system.

Figure 1.

Kotter’s 8-Step Process for Leading Change

Self-perception of current role

Another study by Rosenthal et al.13 examined pharmacists’ first response when asked, “What does a pharmacist do?” Forty-five percent of pharmacists gave a product-focused definition of their role, compared with only 29% who gave a patient-centred answer (Table 1).13,14 This seemingly contrasts with a 2009 study on Canadian community pharmacists’ perception of their role potential in primary care.15 This study surveyed pharmacists about tasks they felt were important for them to complete. There was an overwhelming support for expanded tasks, such as medication selection and monitoring drug therapy.15 I believe this can be explained by the specifics of how pharmacists currently practise.

Table 1.

Definitions of dispensing and patient-focused care14

| Dispensing (product-focused care) | Interpretation and evaluation of a prescription, selection and manipulation or compounding of a pharmaceutical product, labelling and supply of the product in an appropriate container according to legal and regulatory requirements, and the provision of information and instructions by a pharmacist, or under the supervision of a pharmacist, to ensure the safe and effective use by the patient. |

| Patient-focused care | The merging of several models of health care practice including patient education, self-care and evidence-based care into 4 broad areas of intervention: communication with patients, partnership with patients, health promotion and delivery of care. |

WINNER OF CAPSI 2013 STUDENT LITERARY CHALLENGE

Pharmacists traditionally have served an unofficial role in recommending and monitoring drug therapy through suggestions to prescribers. The expanding scope of practice largely permits pharmacists the authority and responsibility to manage those decisions independent of a prescriber. As noted by Rosenthal et al.,10 this would move pharmacists to the forefront of primary care and force pharmacists to risk more judgment from both the patient and the physician. This puts pharmacists into an area in which they are generally uncomfortable. Pharmacists may feel they already are practising in an expanded capacity and thus it makes little sense to support additional changes that would only increase the potential risks to themselves, with no foreseeable benefit to the health care system or their practice. Ultimately, there is no perceived sense of urgency to promote practice change, and many pharmacists have remained resistant to the changes within their profession.

Will pharmacists always be essential?

There is also the self-perceived essentialness of pharmacists in the dispensing process. Pharmacists pride themselves on being able to provide information to patients to ensure safe and effective prescription use and view themselves as drug experts who can provide meaningful and relevant drug information to patients and other health care providers. While this is an important role in health care, nearly half of pharmacists have made it their primary concern over patient-focused activities.15 The reality is that new technologies and procedures are increasingly reducing the need for pharmacists in the dispensing process and basic drug information purposes. Technician regulation in Alberta has granted a large portion of the dispensing process to technicians.16 Technologies such as electronic health records and telehealth, along with registered technicians, are currently used in Alberta hospitals to permit assessment of prescriptions by only a few pharmacists within a remote dispensary for hundreds of patients. It is not unlikely that community pharmacies will adopt a similar model if it proves cost-effective. Additionally, improved technology is providing other health care providers access to easy-to-use drug information and interaction checks, which again reduces the necessity of pharmacists in these areas. Many pharmacists mistakenly believe that dispensing and drug information will provide a reliable and stable future, and this belief contributes to the difficulties many pharmacists have in accepting the risks of their expanded scope.

Going forward: Embracing changes and new futures

Much research has been conducted to determine what pharmacists believe is holding back their profession, but more is needed to truly discern the role pharmacists have in this. The current views that pharmacists are already fulfilling their expanded role in health care and that their current positions are essential have led many pharmacists to view change as unnecessary. Without the belief of necessity, the likelihood of a successful change process will be greatly reduced. However, an increasing proportion of pharmacists view their role as patient-focused and have taken the steps to advance their practice. Enrollment in Alberta’s Additional Prescribing Authorization (APA) continues to increase, and more than 5% of pharmacists have obtained their APA.8 It is hoped that this signals that pharmacists are becoming aware of the necessity of their expanded scope and will embrace their new position in the primary care system. ■

Footnotes

At the time of writing, Joshua Torrance was a student of the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding:The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, et al. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:955-64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schumock GT, Butler MG, Meek PD, et al. Evidence of the economic benefit of clinical pharmacy services: 1996-2000. Pharmacotherapy 2003;23:113-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malone DC, Carter BL, Billups SJ, et al. An economic analysis of a randomized, controlled, multicenter study of clinical pharmacist interventions for high-risk veterans: the IMPROVE study. Pharmacotherapy 2000;20:1149-58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centered care. BMJ 2001;322:444-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bergson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA 2006;296:2848-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Preference of patients for patient centered approach to consultation in primary care: observational study. BMJ 2001;322:1-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alberta Health. Ministerial Order 23/2013. Edmonton (AB): Alberta Health; 2013. Available: http://www.health.alberta.ca/documents/MO-23-2014-PharmacyCompensation.pdf (accessed Oct. 15, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alberta College of Pharmacists. 2012-2013 annual report. Edmonton (AB): Alberta College of Pharmacists; 2013. Available: https://pharmacists.ab.ca/Content_Files/Files/AR2012-13_May13.pdf (accessed Oct. 14, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alberta Pharmacists’ Association. Pharmacy service framework in numbers. RxPress 2013;13:14 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosenthal MM, Austin Z, Tsuyuki RT. Are pharmacists the ultimate barrier to pharmacy practice change? Can Pharm J (Ott) 2010;143:37-42 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotter International. The 8-step process for leading change. Available: www.kotterinternational.com/our-principles/changesteps (accessed Oct. 14, 2013).

- 12. Tsuyuki RT, Schindel TJ. Changing pharmacy practice: the leadership challenge. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2008;141:174-80 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rosenthal MM, Breault RR, Austin Z, Tsuyuki R. Pharmacists’ self-perception of their professional role: insights into community pharmacy culture. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2011;51:363-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Canadian Pharmacists Association. Blueprint for pharmacy: implementation plan. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2011. Available: http://blueprintforpharmacy.ca/docs/pdfs/2011/05/11/BlueprintImplementationPlan.pdf?Status=Master (accessed Oct. 14, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dobson RT, Taylor JG, Henry CJ, et al. Taking the lead: community pharmacists’ perception of their role potential within the primary care team. Res Social Adm Pharm 2009;5:327-36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Government of Alberta. Alberta regulation 129/2006: health professions act: pharmacists and pharmacy technicians profession regulation. Edmonton (AB): Government of Alberta; 2006. Available: http://142.229.230.30/1266.cfm?page=2006_129.cfm&leg_type=Regs&isbncln=9780779758197&display=html (accessed Oct. 14, 2013). [Google Scholar]