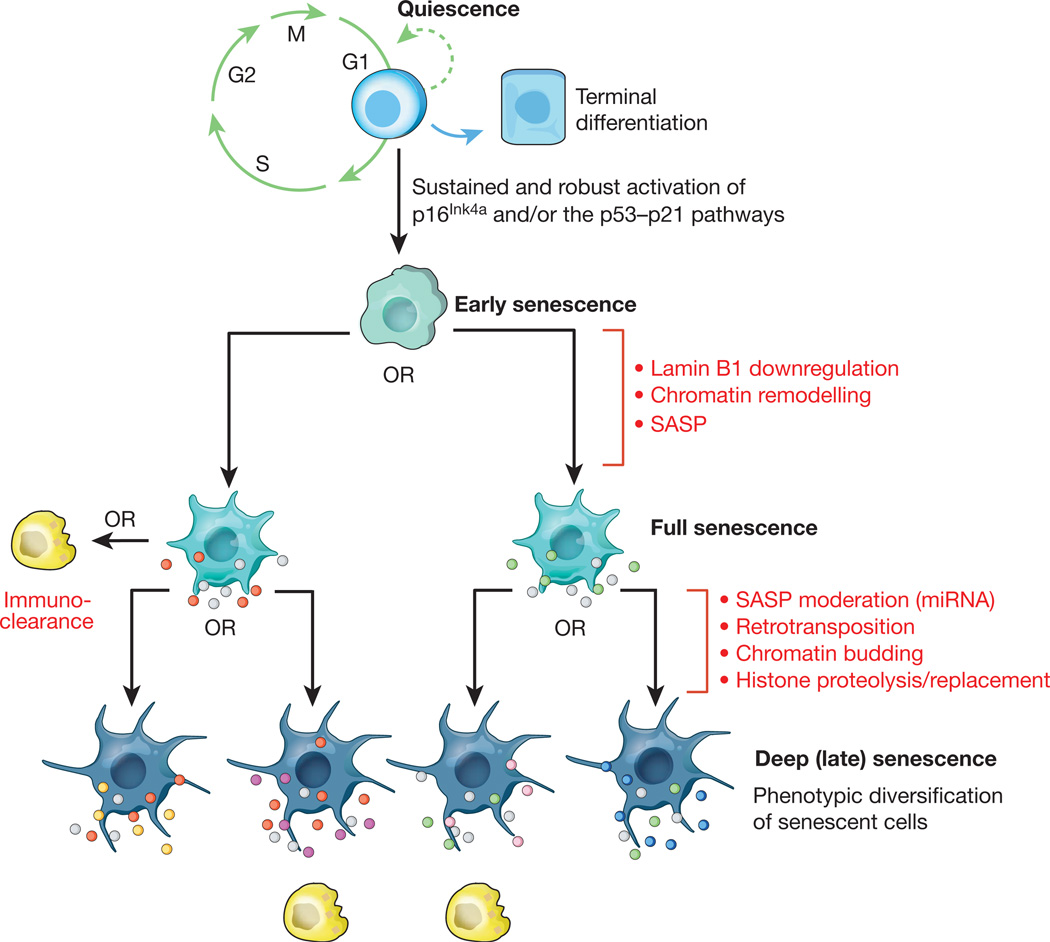

Figure 2. Hypothetical multi-step senescence model.

Mounting evidence suggests that cellular senescence is a dynamic process driven by epigenetic and genetic changes. The initial step represents the progression from a transient to a stable cell-cycle arrest through sustained activation of the p16Ink4a and/or p53–p21 pathways. The resulting early senescent cells progress to full senescence by downregulating lamin B1, thereby triggering extensive chromatin remodelling underlying the production of a SASP. Certain components of the SASP are highly conserved (grey dots), whereas others may vary depending on cell type, nature of the senescence-inducing stressor, or cell-to-cell variability in chromatin remodelling (red and green dots). Progression to deep or late senescence may be driven by additional genetic and epigenetic changes, including chromatin budding, histone proteolysis and retrotransposition, driving further transcriptional change and SASP heterogeneity (yellow, magenta, pink and blue dots). It should be emphasized that although the exact nature, number and order of the genetic and epigenetic steps occurring during senescent cell evolution are unclear, it is reasonable to assume that the entire process is prone to SASP heterogeneity. The efficiency with which immune cells (yellow) dispose of senescent cells may be dependent on the composition of the SASP. Interestingly, the proinflammatory signature of the SASP can fade due to expression of particular microRNAs late into the senescence program, thereby perhaps allowing evasion of immuno-clearance99.