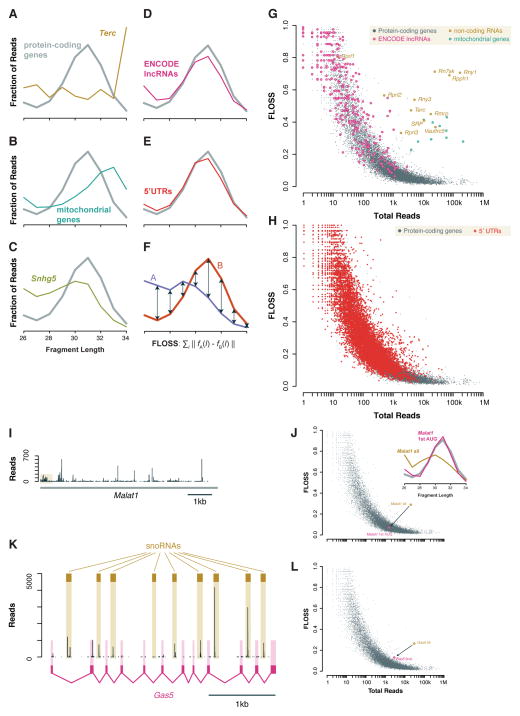

Figure 1. Fragment length analysis distinguishes true ribosome footprints on coding and non-coding sequences.

(A – E) Distribution of fragment lengths mapping to nuclear coding sequences (CDSes) compared to (A) the telomerase RNA Terc, (B) mitochondrial coding sequences, (C) snoRNA host gene Snhg5, (D) ENCODE lncRNAs, and (E) 5′ UTRs of protein-coding genes, in ribosome profiling data from emetine-treated mESCs. (F) Metric comparing the similarity of two length distributions. (G) Fragment length analysis plot of total reads per transcript and FLOSS relative to the nuclear coding sequence average. An FLOSS cutoff is based on an extreme outlier threshold for annotated coding sequences. LncRNAs resemble annotated, nuclear protein-coding genes, whereas functional RNAs and mitochondrial coding sequences are distinct. (H) As (G), comparing 5′ UTRs and coding sequences of nuclear-encoded mRNAs. (I) Read count profile on Malat1 with an inset showing ribosomes on a non-AUG uORF and the first reading frame at the 5′ end of the transcript. An inset shows the fragment length distribution for the first reading frame, which matches the overall coding sequence average, and the whole transcript, which does not. (J) Fragment length analysis showing the shift from the entire Malat1 transcript, which contains substantial background, to the first Malat1 reading frame, which contains true ribosome footprints. (K) Read count profile acros the primary Gas5 transcript with the snoRNAs and the fully-spliced transcript shown. (L) As (J) for the primary Gas5 transcript, containing snoRNA precursors, and the fully spliced product.