Abstract

We recently introduced sulfated pentagalloylglucopyranoside (SPGG) as an allosteric inhibitor of factor XIa (FXIa) (Al-Horani et al., J. Med Chem. 2013, 56, 867–878). To better understand the SPGG–FXIa interaction, we utilized eight SPGG variants and a range of biochemical techniques. The results reveal that SPGG’s sulfation level moderately affected FXIa inhibition potency and selectivity over thrombin and factor Xa. Variation in the anomeric configuration did not affect potency. Interestingly, zymogen factor XI bound SPGG with high affinity, suggesting its possible use as an antidote. Acrylamide quenching experiments suggested that SPGG induced significant conformational changes in the active site of FXIa. Inhibition studies in the presence of heparin showed marginal competition with highly sulfated SPGG variants but robust competition with less sulfated variants. Resolution of energetic contributions revealed that nonionic forces contribute nearly 87% of binding energy suggesting a strong possibility of specific interaction. Overall, the results indicate that SPGG may recognize more than one anion-binding, allosteric site on FXIa. An SPGG molecule containing approximately 10 sulfate groups on positions 2 through 6 of the pentagalloylglucopyranosyl scaffold may be the optimal FXIa inhibitor for further preclinical studies.

Introduction

The clinical burden of venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains high despite advances in the design of new anticoagulants. It is estimated that annual VTE incidence is approximately 500–1200 per million people and the second episode incidences increase nearly 10–40%.1 A key reason for the occurrence of second episodes is the adverse effects associated with all anticoagulants used today, which limit a physician’s employment of an effective, long-term strategy. Two major classes of traditional anticoagulants, heparins and coumarins, suffer from elevated bleeding tendency in addition to other agent-specific adverse effects. Recent introduction of target-specific oral anticoagulants (TSOAs), including dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban, was expected to eliminate bleeding risk, yet growing number of studies are suggesting that bleeding continues to be a problem in measures that at times is equivalent to that observed with warfarin.2−4 Further, the TSOAs suffer from nonavailability of an effective antidote to rapidly reverse bleeding consequences without raising the possibility of thrombosis. Another aspect that is being brought to light is the high protein binding capability of TSOAs, especially rivaroxaban and apixaban, which thwarts efforts to reduce their anticoagulant effects through dialysis.

Current anticoagulants target two key enzymes of the common pathway of the coagulation cascade, thrombin and factor Xa. Whereas the heparins and coumarins indirectly target the two pro-coagulant enzymes, the TSOAs target them directly. No molecule has reached the clinic that targets other enzymes of the cascade to date. Yet, several other protein/enzyme targets are viable alternatives, including factors Va, VIIa, VIIIa, IXa, XIa and XIIa, and are beginning to be pursued.5 The logic in pursuing these factors is that blocking a side arm of a highly interlinked system is likely to only partially impair the system and not induce complete dysfunction. Thus, inhibiting factors belonging to either the intrinsic or extrinsic pathway of coagulation can be expected to reduce thrombotic tendency while maintaining blood’s natural ability to clot.

One coagulation factor that is gaining keen interest with regard to developing safer anticoagulant therapy is factor XIa (FXIa). Several epidemiological observations in humans and investigational studies in animals indicate that inhibiting FXIa is likely to be associated with minimal risk of bleeding. Severe factor XI deficiency (10–20% of the normal) appears to protect against venous thrombosis6 and ischemic stroke.7 Likewise, hemophilia C, a genetic defect arising from loss of function mutations in the factor XI gene, results only in mild bleeding consequences and this can be easily corrected by replacement with soluble, recombinant zymogen, factor XI.8−11 With regard to studies in mice, targeted deletion of the factor XI gene resulted in a complete absence of occlusive clot formation in FeCl3-induced carotid artery12 and inferior vena cava thrombosis models.13 Yet, interestingly, the deletion did not affect tail bleeding times, suggesting an absence of a hemostatic defect.12,14 Similar results were obtained with studies in the baboon,15,16 rabbit,17 and rat.18 These studies lead to the growing evidence that inhibiting the factor XI arm of coagulation affects the pathologic consequences of coagulation more than the hemostatic function. Thus, a new paradigm gaining support in terms of anticoagulation therapy is that inhibitors of FXIa may exhibit a much safer profile than that observed with current TSOAs, heparins, and coumarins.

Human FXIa is a 160 kDa disulfide-linked homodimer. Each monomer contains a N-terminal heavy chain made up of four tandem Apple domains A1 through A4 and a C-terminal light chain containing the trypsin-like catalytic domain.19,20 No other coagulation enzyme is known to function in vivo as a dimer, and FXIa is unusually interesting factor in this respect. Another special structural feature of FXIa is that it possesses multiple regions of high electropositivity, which can engage highly anionic molecules such as sulfated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), particularly heparin,21−24 and polyphosphate.25 FXIa possesses heparin-binding sites in the A3 domain of the heavy chain (K252, K253, and K255)21,22 and in the catalytic domain (K529, R530, R532, K536, and K540).23,24 Whereas the A3 domain site is primarily involved in template-mediated processes, such as ternary complexation with plasma glycoprotein antithrombin, the catalytic domain site is more involved in allosteric modulation of FXIa’s functional activity, resulting in inhibition of both small peptide and macromolecular substrate cleavage.23,24,26 Another region of high electropositivity arises from the R504, K505, R507, and K509 group of residues located in the autolysis loop of FXIa, which also contributes to modulation of serpin specificity.24

The heparin-binding sites on coagulation factors present major opportunities for developing novel coagulation modulators of the future.27 These sites are typically cooperatively linked to the catalytic site, as demonstrated particularly for FXIa,26 which affords the ability to allosterically inhibit the enzyme. Allosteric inhibition of coagulation enzymes is a novel paradigm for developing clinically relevant anticoagulants and offers major advantages over the traditional orthosteric inhibition mechanism employed today. Whereas active site inhibitors offer dose as the only parameter for fine modulation of the anticoagulation state, allosteric inhibitors can offer two independent parameters, dose and efficacy, to induce a targeted anticoagulation state. Allosterism relies on the efficiency of transmission of energy from the remote site to the catalytic site. This energetic coupling inherently depends on the structure of the ligand, which may or may not induce full conformational change, resulting in efficacy that is decoupled from the level of saturation of the allosteric site, i.e., the dose. This can result in variable efficacies of inhibition (<100%) that may prove to be value in developing safer anticoagulants. That it is possible to achieve variable efficacy of inhibition has been recently shown for few sulfated benzofurans inhibiting thrombin.28,29

Despite the advantages of allosteric inhibitors, most of synthetic small molecules reported to inhibit FXIa are orthosteric inhibitors. These include several scaffolds such as neutral cyclic peptidomimetics,30 arginine-containing acyclic peptidomimetics,31−33 aryl boronic acids,34 bromophenolic carbamates,35 and tetrahydroisoquinolines,36 which are being pursued at various levels. We recently discovered three types of sulfated allosteric inhibitors of FXIa including sulfated pentagalloylglucoside (SPGG),37 sulfated quinazolinone (QAO),38 and monosulfated benzofurans.39 Whereas SPGG was based on a polysulfated aromatic scaffold, sulfated QAO and benzofurans were based on a monosulfated hydrophobic scaffold. Although structurally completely different, these groups of molecules allosterically inhibited FXIa and induced human plasma anticoagulation. However, much remains to be understood for advancing the paradigm of allosteric anticoagulants introduced by these interesting molecules. In this work, we study the interaction of SPGG and its eight variants at a molecular level to elucidate aspects of structure–function relationships, the forces involved in this interaction, and the mechanism of inhibition. We find moderate variation in potency of FXIa inhibition as a function of SPGG’s sulfation level but no effect on the efficacy and allosteric mechanism of inhibition. Further, chemical synthesis of a representative molecule of the most abundant species, i.e., decasulfated species, revealed comparable inhibition, efficacy, and specificity profiles to the parent SPGG variants. Interestingly, despite the presence of significant number of anionic groups, nonionic forces dominate the SPGG–FXIa interaction under physiologic conditions. Further, SPGG was found to bind both FXIa and its zymogen factor XI with similar affinities. Most interestingly, competitive inhibition studies in the presence of heparin suggest that different SPGG variants appear to recognize different anion-binding sites. These results enhance fundamental understanding on SPGG–FXIa interaction and suggest avenues for further rational design of advanced molecules.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Characterization of Variants of SPGG

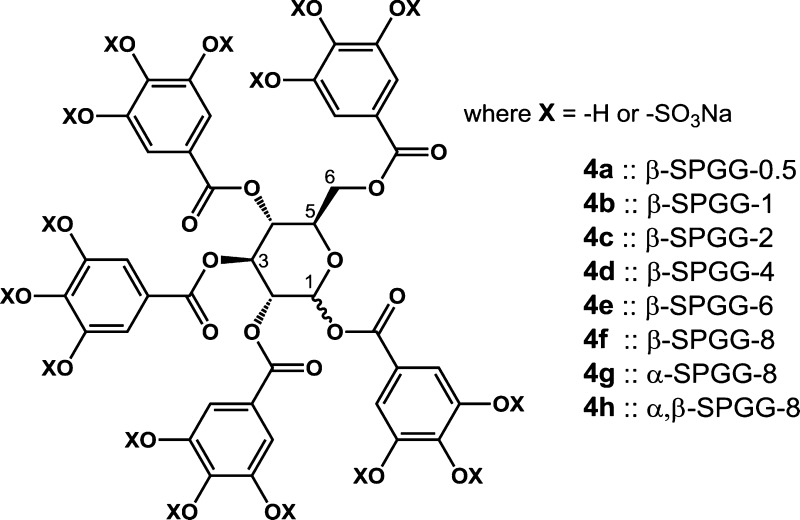

Our previous work reported the discovery of SPGG,37 which is labeled as β-SPGG-2 (4c, see Scheme 1) in this work for appropriateness and clarity. β-SPGG-2 was synthesized using a three-step protocol involving DCC-mediated esterification of β-d-glucopyranose with 3,4,5-tribenzyloxybenzoic acid followed by palladium-catalyzed hydrogenation to obtain precursor 3a. The polyphenolic precursor 3a was sulfated under microwave conditions for 2 h at 90 °C using trimethylamine–sulfur trioxide complex to prepare β-SPGG-2.37 The label refers to a SPGG variant containing the β anomer of glucose and prepared following 2 h of sulfation.37 This initial discovery of potent antifactor XIa activity, which was found to translate to potent anticoagulation in human plasma and blood, brought forward questions on the roles of anomeric configuration, level of sulfation, and nature of forces involved in binding.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of SPGG Derivatives (4a–4h) and the Decasulfated Species (5).

(a) 3,4,5-Tribenzyloxybenzoicacid or 3,5-dibenzyloxybenzoic acid (5 equiv), DCC (5 equiv), DMAP (5 equiv), CH2Cl2, reflux, 24 h, 85–90%; (b) H2 (g) (50 psi), Pd(OH)2/C (20%), CH3OH/THF, rt, 10 h, >92%; (c) N(CH3)3-SO3 (5 equiv/OH), CH3CN (2 mL), MW, 90 °C, 0.5–8 h, 66–72%.

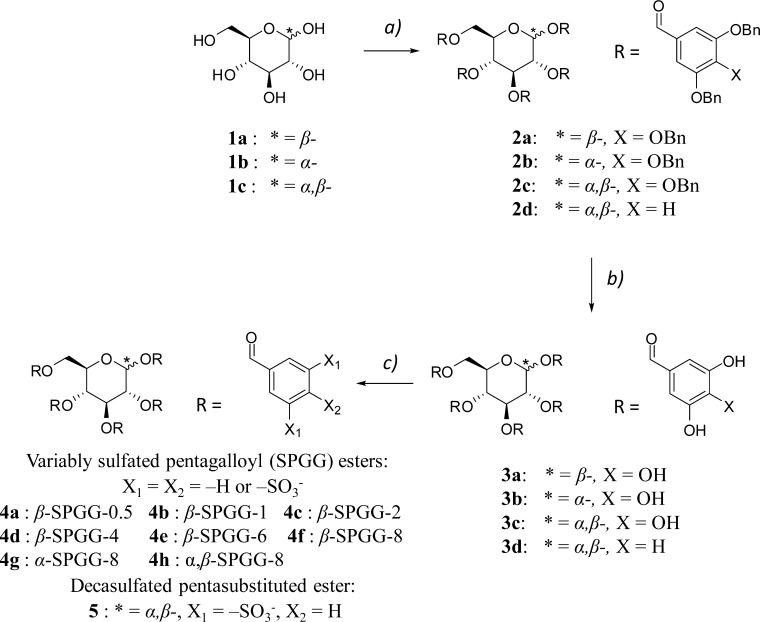

High resolution UPLC-MS analysis indicated that β-SPGG-2 (4c) was composed of hepta- to dodeca-sulfated species (Figure 1A). A simple analysis suggests that 455–6455 distinct hepta- to dodeca-sulfated species are theoretically possible for β-SPGG-2, although some of these are more easily formed than others. We reasoned that the potency of β-SPGG-2 could be significantly improved through a higher level of sulfation, which could also help enhance the homogeneity of the preparation. In fact, if the precursor can be per-sulfated, a single homogeneous product can be realized. Yet, per-sulfation of polyphenolics is extremely difficult and no per-sulfated molecule has been synthesized to date that contains pentadeca sulfate groups on a small scaffold, such as that of pentagalloyl glucopyranoside (PGG) (3a–3c) (Scheme 1). Yet, we hypothesized that the proportion of undeca-, dodeca-, and higher sulfated species could be enhanced by extending the sulfation time. Thus, variants including β-SPGG-0.5 (4a), β-SPGG-1 (4b), β-SPGG-2 (4c), β-SPGG-4 (4d), β-SPGG-6 (4e), and β-SPGG-8 (4f) were synthesized by sulfation of β-PGG (3a) for 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h, respectively, under otherwise identical conditions. Likewise, α-SPGG-8 (4g) and α,β-SPGG-8 (4h) were synthesized by sulfating α-PGG (3b) and PGG (3c), each obtained from the respective α-d-glucose and α,β-d-glucose, for 8 h. The configuration of the anomeric carbon in each variant was determined by measuring the [α]D20 in acetone (c = 1%) of the corresponding polyphenolic precursor. Consistent with literature,40 the specific rotations of the precursors were found to be +25.2° for β-, +65.5° for α-, and +57.9° for α,β-derivative.

Figure 1.

Reversed phase-ion pairing UPLC–MS analysis of β-SPGG-2 (4c) (A) and β-SPGG-8 (4f) (B). Both 4c and 4f (and likewise other SPGG variants 4a–4h) could be resolved into peaks corresponding to components with varying levels of sulfation from hepta- to trideca-sulfated PGG scaffold (see also Supporting Information Figures S1 and S2). The proportion of higher sulfated species increases from 4a through 4h.

The detailed compositional profile of these SPGG variants was measured using reversed-phase ion-pairing UPLC-ESI-MS analysis, as described in our earlier work.37 For variants 4c and 4f, the profiles indicated the presence of doubly charged molecular ion peaks at 1207, 1297, 1388, 1478, 1569, 1661, and 1750 m/z, which corresponded to hepta-, octa-, nona-, deca-, undeca-, dodeca-, and trideca- sulfated species, respectively (Figure 1). Each of these peaks was a composite of multiple peaks, which implied the presence of several regioisomers of identical sulfation level. The proportion changed from 5 (hepta-), 10, 19, 42, 17, 7, and 0 (trideca-) % for 2 h sulfation to 3, 8, 18, 34, 24, 8 and 5% for 8 h sulfation, respectively. This implied that tridecasulfated species were present in β-SPGG-8 (4f, Figure 1B) but not in β-SPGG-2 (4c). Likewise, the proportion of undeca- and dodeca- sulfated species increased as the sulfation time increased from 2 to 8 h. In contrast, shortening the sulfation time to 0.5 h resulted in absence of dodeca- and tridecasulfated species in β-SPGG-0.5 (see Figure S1 and Table S1 in Supporting Information). The microwave synthesis of the different variants was highly reproducible as assessed by the similarity of UPLC-ESI-MS profiles across at least three independent synthetic batches (Supporting Information Figures S1,S2 and Table S1). Using the distribution of peaks and their corresponding molecular masses, the average molecular weights (Mr) of the Na+ forms of β-SPGG-0.5 (4a), β-SPGG-1 (4b), β-SPGG-2 (4c), β-SPGG-4 (4d), β-SPGG-6 (4e), and β-SPGG-8 (4f) were calculated to be 1923, 1940, 1962, 1975, 1960, and 1982, respectively. Likewise, the UPLC-ESI-MS profiles for α-SPGG-8 (4g) and α,β-SPGG-8 (4h) indicated Mr values of 2071 and 2090, respectively (Supporting Information Figures S1,S2 and Table S1). The Mr data suggests a difference of ∼190 Da between β-SPGG-0.5 and α,β-SPGG-8, which could be thought of as an increase of two −OSO3Na groups.

A decasulfated species (5) was also synthesized as a representative SPGG molecule in an essentially homogeneous form corresponding to the most abundant species present in each SPGG variant. Molecule 5 was synthesized using the protocol described above, except for replacing 3,4,5-tribenzyloxybenzoic acid with 3,5-dibenzyloxybenzoic acid. Following esterification, hydrogenation, and sulfation, 5 was obtained in quantitative yields. NMR and UPLC-MS were used to establish its structural homogeneity and chemical identity. Molecule 5 was found to have 10 sulfate groups, as expected based on per-sulfation, with a molecular weight of 1438.71 (see Supporting Information).

Inhibition of FXIa by SPGG Variants

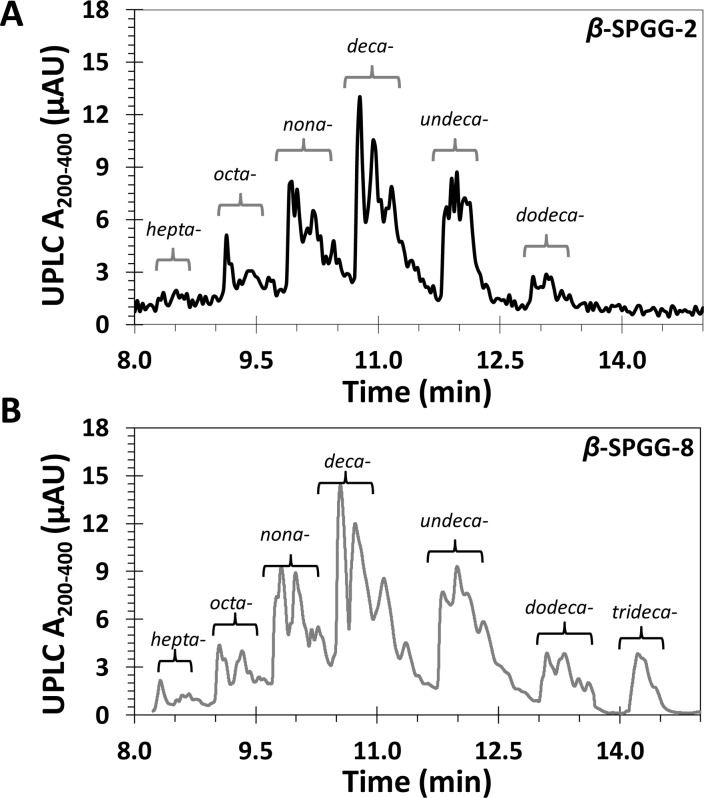

Each SPGG variant was evaluated for its potential to inhibit FXIa hydrolysis of S-2366, a chromogenic small peptide substrate, at pH 7.4 and 37 °C. A dose-dependent reduction in FXIa activity was observed (Figure 2), which was analyzed using the logistic eq 1. The IC50s spanned 0.15–1.77 μg/mL (72–920 nM), reflecting a moderate range of potencies (Table 1). The efficacies were found to be in the range of 84–100%, with Hill slopes in the range of 1.0–1.6 (except for 4a). This implies that extending the sulfation time from 2 (β-SPGG-2) to 8 h (β-SPGG-8) improved the potency by ∼5-fold without any significant effect on the efficacy or Hill slope of inhibition. Interestingly, altering the anomeric carbon configuration (α-, α,β-, or β-) did not appear to impact in any meaningful way. Thus, the three −OSO3Na groups present on aryl moiety of the anomeric carbon are not involved in interaction with FXIa. This may imply that the C-1 aromatic ring could be replaced with a C-1 methyl group without affecting potency. Interestingly, shortening the sulfation time from 2 to 1 h did not significantly reduce the potency (0.80–1.01 μg/mL), but further decrease in the sulfation time to 0.5 h significantly reduced the potency by more than 2-fold (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Direct inhibition of full-length factor XIa by variably sulfated SPGG variants as well as the synthesized decasulfated species. The inhibition of factor XIa by 4f (○), 4e (●), 4d (Δ), 4c (■), 4b (◇), 4a (▲), and 5 (□) was studied at pH 7.4 and 37 °C, as described in Experimental Procedures. Solid lines represent sigmoidal dose–response fits using eq 1 to the data to calculate the IC50, ΔY, and HS values.

Table 1. Inhibition Parameters for SPGG Variantsa.

| factor XIa |

thrombin | factor Xa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mr | IC50 (μg/mL) | IC50 (nM) | HS | ΔY | IC50 (μg/mL) | IC50 (μg/mL) | |

| β-SPGG-0.5 (4a) | 1923 | 1.77 ± 0.05b | 920 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 94 ± 3 | ∼403c | >2375 |

| β-SPGG-1 (4b) | 1940 | 1.01 ± 0.05 | 521 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 93 ± 4 | ∼381 | 770 ± 103 |

| β-SPGG-2 (4c) | 1962 | 0.80 ± 0.02 | 408 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 100 ± 2 | >500 | ∼338 |

| β-SPGG-4 (4d) | 1975 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 203 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 98 ± 2 | >500 | ∼634 |

| β-SPGG-6 (4e) | 1960 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 153 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 92 ± 3 | ∼323 | ∼495 |

| β-SPGG-8 (4f) | 1982 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 76 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 97 ± 2 | >500 | ∼515 |

| α-SPGG-8 (4g) | 2071 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 72 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 95 ± 3 | ∼657 | 244 ± 14 |

| α,β-SPGG-8 (4h) | 2090 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 77 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 84 ± 2 | ∼237 | 207 ± 43 |

| 5 | 1439 | 2.70 ± 0.03 | 1420 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 100 ± 4 | >213 | >798 |

IC50, HS, and ΔY values were obtained following nonlinear regression analysis of direct inhibition of human factor XIa, thrombin, and factor Xa in pH 7.4 buffer at 37 °C. Inhibition was monitored by spectrophotometric measurement of the residual enzyme activity. See details under Experimental Procedures.

Errors represent standard error calculated using global fit of the data.

Estimated value based on the highest concentration of the inhibitor used in the experiment.

FXIa inhibition by decasulfated derivative 5 was generally similar to β-SPGG-2 (4c) except for its ∼3.5-fold reduced potency. This suggested that the 10 sulfate groups carry good FXIa inhibition potential but not the best. The result further supports the idea that specific 3-D orientation of groups on the SPGG scaffold are important for optimal FXIa inhibition. One plausible reason for the reduced potency exhibited by 5 is the absence of phenolic group at the para positions. It is possible that these p-OH groups in the most abundant species present in β-SPGG-8 and/or β-SPGG-2 enhance potency through hydrogen bonding. Another explanation is that other decasulfated regioisomers with a different pattern of 3,4- or 3,5-disulfates may be more important.

Inhibition of Factor Xa and Thrombin by SPGG Variants

To assess the specificity features of SPGG variants, two closely related coagulation enzymes were studied. Using appropriate small peptide-based chromogenic substrates, the fractional residual thrombin and factor Xa activities were measured. The SPGG variants displayed 228–3433-fold selectivity against thrombin and factor Xa (Table 1). This implies a high level of specificity for targeting FXIa. More specifically, β-SPGG-0.5 (4a) and β-SPGG-1 (4b) appear to exhibit equivalent or better selectivity profile relative to β-SPGG-2 (4c) despite the slight reduction in potency against FXIa. On the other hand, higher sulfated species, e.g., 4g and 4h, displayed lower selectivity index against thrombin and factor Xa (Table 1). Also, α-isomeric variants appear to inhibit factor Xa (IC50 = 207 or 244 μg/mL) but are not worth studying further because of weak potency (>100 μM). Finally, the decasulfated derivative 5 was found to maintain a good selectivity against both thrombin and FXa (>79-fold and 296-fold, respectively).

Kinetics of β-SPGG-8 (4f) Inhibition of FXIa

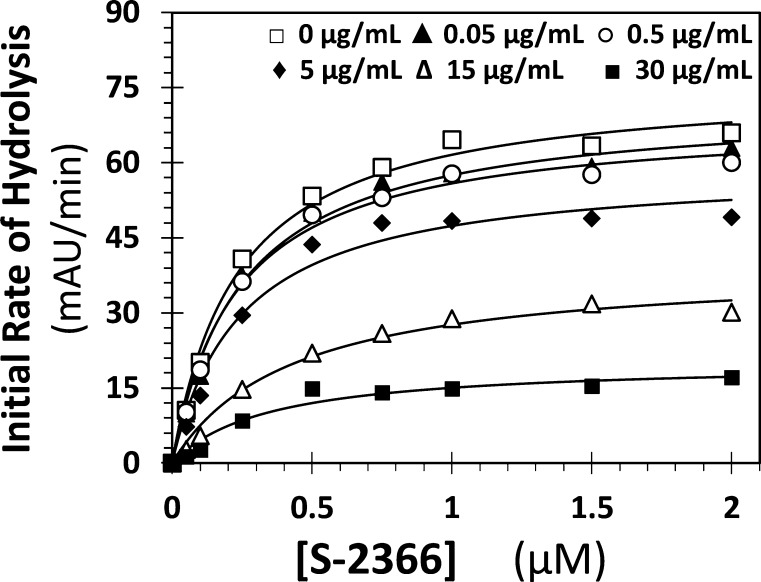

Earlier, we reported that β-SPGG-2 (4c) is an allosteric inhibitor of factor XIa.37 To assess whether a higher level of sulfation alters this mechanism, the kinetics of S-2366 hydrolysis by full-length human FXIa was performed in the presence of 0–30 μg/mL β-SPGG-8 at pH 7.4 and 37 °C (Figure 3). The characteristic hyperbolic profiles were fitted using the standard Michaelis–Menten kinetic equation to calculate the apparent KM and VMAX (see Supporting Information Table S2). The KM for S-2366 remained essentially invariant (0.24–0.36 mM), while the VMAX decreased steadily from 76 ± 2 mAU/min in the absence of β-SPGG-8 to 20 ± 2 mAU/min at 30 μg/mL β-SPGG-8. This implies that β-SPGG-8 does not affect the formation of Michaelis complex but induces a significant dysfunction in the catalytic apparatus, suggesting a noncompetitive inhibition mechanism. Thus, higher sulfation of the SPGG scaffold does not change the mechanism of factor XIa inhibition and presumably intermediate levels of sulfation also retain the noncompetitive mechanism.

Figure 3.

Michaelis–Menten kinetics of S-2366 hydrolysis by full-length factor XIa in the presence of β-SPGG-8. The initial rate of hydrolysis at various substrate concentrations was measured in pH 7.4 buffer as described in Experimental Procedures using the wild-type full-length factor XIa. β-SPGG-8 concentrations are 0 (□), 0.05 (▲), 0.5 (○), 5 (◆), 15 (Δ), and 30 μg/mL (■). Solid lines represent nonlinear regressional fits to the data using the standard Michaelis–Menten equation to calculate the VMAX and KM.

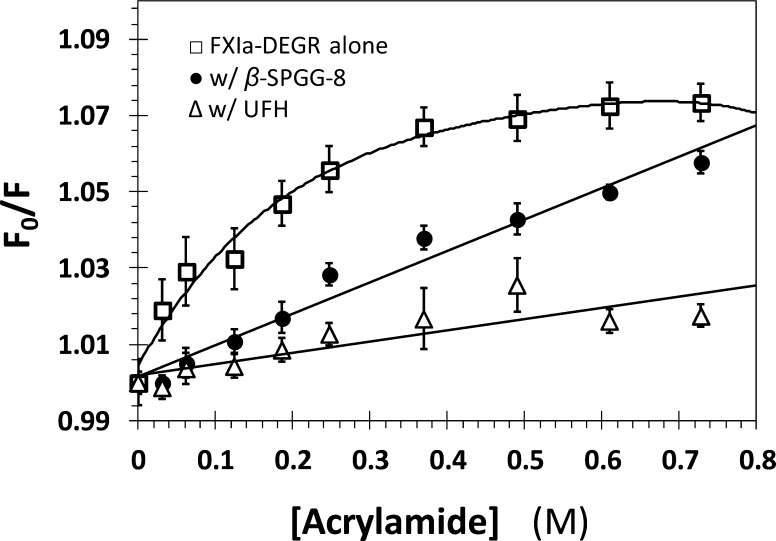

Allosteric Quenching of an Active Site Probe

The kinetic mechanism of inhibition supports the hypothesis that SPGG variants appear to remotely affect the conformation of the catalytic triad of FXIa. We predicted that this effect may extend to regions beyond the catalytic triad. To assess this, we studied the quenching of fluorescence of DEGR-FXIa, a dansyl-labeled variant, by acrylamide in the presence and absence of β-SPGG-8 (4f). DEGR-FXIa contains the fluorophore at the end of the EGR tripeptide (P1–P3 residues), which is covalently attached to the catalytic Ser. This implies that the dansyl group senses the electrostatics and dynamics around the P4 position. Dextran sulfate and hypersulfated heparin have been earlier shown to reduce the quenching of DEGR-FXIa by acrylamide.26 Figure 4 shows the quenching of DEGR-FXIa fluorescence by acrylamide with and without 20 μM β-SPGG-8 or 20 μM UFH. Acrylamide quenches FXIa’s fluorescence both in the absence and presence of ligands in a dose-dependent manner. Yet, the efficiency of quenching is dramatically different. Whereas considerable saturation is observed for FXIa alone with increasing quencher concentrations, no such effect is noted in the presence of the two allosteric ligands. Considering that FXIa is a physiological dimer,18,19 the significant nonlinearity of quenching suggests the possibility of two slightly different fluorophores, which are being differentiated by the quencher. Indeed, it is possible to isolate FXIa with only half-functional unit.18,19 This implies that acrylamide is able to sense protein dynamics for dimeric FXIa. In contrast, both β-SPGG-8 and UFH stem quenching to only about 50% of that observed in their absence at 350 mM acrylamide. At the same time, essentially no saturation of quenching is observed in their presence. In fact, the profiles follow the traditional one-fluorophore Stern–Volmer linear relationship well. This suggests that either one or both dansyl fluorophore(s) is(are) sterically less accessible to the quencher all or part of the time. A simple explanation for this behavior is that both β-SPGG-8 and UFH induce conformational changes in and around the active site that reduce steric and dynamic accessibility to probes as small as the acrylamide.

Figure 4.

Quenching of dansyl fluorescence of DEGR-factor XIa by acrylamide in the absence (□) and presence of 20 μM β-SPGG-8 (●) and 20 μM UFH (Δ). Fluorescence intensity at 547 (λEX = 345 nm) was recorded following sequential addition of acrylamide. Solid lines represents fits to the data using either eq 2 (●, Δ) or 3 (□).

Thermodynamic Affinity of SPGG Variants for FXIa

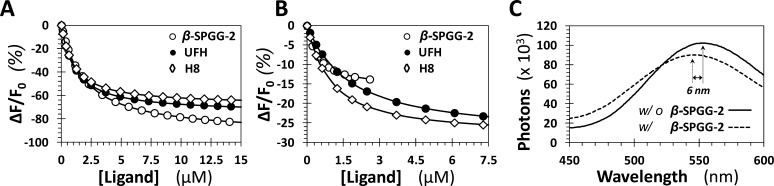

Although the inhibition potency of SPGG variants has been rigorously defined, their thermodynamic affinity remains unknown. A fundamental question that arises here is whether thermodynamic affinity, i.e., KD, is in the range of IC50 as predicted by Cheng and Prusoff41 for allosteric inhibitors. In general, the affinity of saccharide and nonsaccharide ligands for various coagulation proteins, such as antithrombin, thrombin, and FXIa, have been measured using intrinsic42−44 as well as extrinsic38,45 fluorescence probes. For example, heparins induce a 30–40% increase in intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of antithrombin,42 while sucrose octasulfate decrease the intrinsic fluorescence of thrombin by 5–10%.44 For nonsaccharide ligands, sulfated tetrahydroisoquinolines45 and low molecular weight lignins43 induce a decrease in antithrombin and plasmin fluorescence, while sulfated QAO dimers induce a 50–90% increase in the fluorescence of DEGR-FXIa.38 Thus, we used both tryptophan and dansyl as probes of FXIa interaction to measure the affinity of β-SPGG-2 (4c), β-SPGG-8 (4f), UFH, and H8.

A saturating decrease of ∼94% in the intrinsic fluorescence of FXIa was measured for β-SPGG-2 at pH 7.4 and 37 °C, which could be fitted using the standard quadratic binding eq 4 to calculate a KD of 2.0 ± 0.2 μM (Figure 5A). Likewise, β-SPGG-2 binding to DEGR-FXIa induced a 16 ± 1% loss in the fluorescence of the dansyl group (Figure 5B), which implied an affinity of 0.44 ± 0.1 μM (Table 2). It was interesting to find that the emission wavelength of DEGR-FXIa underwent a significant 6 nm blue-shift in the presence of saturating β-SPGG-2 as compared to that in its absence (Figure 5C), further supporting the conclusion of long-range conformational coupling between β-SPGG-2 and the active site of FXIa. The higher sulfated variant β-SPGG-8 displayed very similar properties as β-SPGG-2 (not shown). These findings suggest that β-SPGG-2 (and β-SPGG-8) bind potently to FXIa. The inhibition potency of 0.41 μM for β-SPGG-2 (Table 1) is essentially identical to the thermodynamic affinity of 0.44 μM, supporting the classic allosteric mechanism of inhibition. At the same time, a small difference in affinity was noted for two types of measurements: tryptophan and dansyl fluoresence. At the present time, the reason for this difference is not clear.

Figure 5.

Spectrofluorimetric measurement of the affinity of full-length factor XIa (A) and factor XIa–DEGR (B) for β-SPGG-2, UFH, and H8 at pH 7.4 and 37 °C using intrinsic tryptophan (A, λEM = 348 nm, λEX = 280 nm) or dansyl (B, λEM = 547 nm, λEX = 345 nm) fluorescence. Solid lines represent nonlinear regressional fits using quadratic eq 4. (C) Change in the fluorescence emission spectrum of DEGR-factor XIa (λEX = 345 nm) induced by the interaction with β-SPGG-2 at pH 7.4 and 37 °C.

Table 2. Dissociation Equilibrium Constants (KD) and Maximal Fluorescence Change (ΔFMAX) for the Interactions of SPGG Variants, UFH, and H8 with Human Factor XIa and DEGR-Factor XIaa.

| enzyme | KD (μM) | ΔFMAX (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-SPGG-2 (4c) | factor XIab | 2.0 ± 0.2 | –94 ± 2 |

| DEGR-factor XIac | 0.4 ± 0.1 | –16 ± 1 | |

| β-SPGG-8 (4f) | factor XIa | 1.9 ± 0.2 | –94 ± 2 |

| DEGR-factor XIa | 0.20 ± 0.07 | –16 ± 1 | |

| UFH | factor XIa | 1.1 ± 0.3 | –75 ± 3 |

| DEGR-factor XIa | 1.6 ± 0.5 | –29 ± 2 | |

| H8 | factor XIa | 0.9 ± 0.2 | –68 ± 2 |

| DEGR-factor XIa | 0.9 ± 0.2 | –29 ± 1 | |

Errors represent standard error calculated using global fit of the data.

Measured using the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence change in pH 7.4 buffer at 37 °C. See Experimental Procedures for details.

Measured using the dansyl fluorescence change in pH 7.4 buffer at 37 °C. See Experimental Procedures for details.

To compare the FXIa−β-SPGG-2 interaction with that of UFH and H8, the affinities of the latter two saccharides were measured using intrinsic tryptophan (plasma FXIa) and dansyl fluorescence (DEGR-FXIa). Both UFH and H8 showed a saturating decrease in tryptophan fluorescence, albeit with a smaller ΔFMAX of 75 ± 3% and 68 ± 2%, respectively (Table 2, Figure 5A). In contrast, the ΔFMAX of DEGR-FXIa complexes with UFH and H8 decreased more than that for DEGR-FXIa−β-SPGG-2 complex (Table 2, Figure 5B). The KDs calculated for UFH and H8 by both methods were essentially identical and in-between those measured for β-SPGG-2 using the two probes (Table 2). Finally, the emission wavelength of DEGR-FXIa in the presence of UFH and H8 displayed ∼2 nm and ∼3 nm blue-shift, respectively (see Supporting Information Figure S3), as compared to that in their absence. These results indicate that β-SPGG-2 interaction with FXIa appears to exhibit similar biochemical properties as that for UFH and H8. Measurable differences are evident in the maximal fluorescence changes and affinity for DEGR-FXIa interaction with the three ligands, but overall, these properties suggest that allosteric interaction of β-SPGG-2 with FXIa is generally similar to that of the heparins.

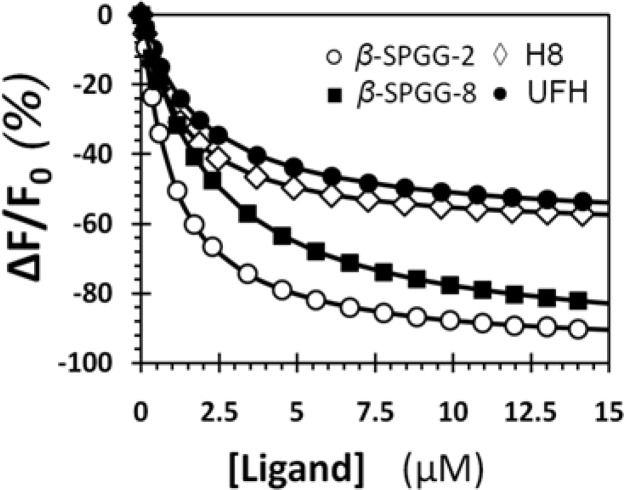

Thermodynamic Affinity of SPGG Variants for Factor XI, the Zymogen

The zymogen factor XI also possesses anion-binding site(s) in the manner similar to FXIa.21,22,46 Although these sites on the zymogen are yet to be fully characterized, we wondered whether SPGG variants would recognize FXI. Such an interaction, if potent and specific, would be extremely useful because it would support the idea that the zymogen could be effectively used as an SPGG scavenging agent in hypothetical events of accidental overdose. The FXI affinities of β-SPGG-2 and β-SPGG-8 were measured using intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence, which decreased by 95–97% at pH 7.4 and 37 °C, giving KDs of 1.0 ± 0.2 and 1.8 ± 0.2 μM, respectively (Figure 6). This is a striking result because it implies that both SPGG variants bind to the zymogen with approximately the same affinity as the enzyme. Although not absolutely necessary, the equivalence of affinities may indicate equivalence of the anion-binding site(s) on the two proteins. Likewise, the affinities of UFH and H8 for FXI were found to be 1.2 ± 0.3 and 1.8 ± 0.4 μM, respectively (Figure 6), suggesting similarity between SPGG variants and sulfated saccharides.

Figure 6.

Spectrofluorimetric measurement of the affinity of full-length factor XI for β-SPGG-2 (○), β-SPGG-8 (■), UFH (●), and H8 (◇) at pH 7.4 and 37 °C using intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (λEM = 348 nm, λEX = 280 nm). Solid lines represent nonlinear regressional fits using quadratic eq 4

Interestingly, SPGG Variants Compete Variably with UFH for Binding to the Catalytic Domain of FXIa

Heparin binds to FXIa in two sites; in the A3 domain (K252, K253, and K255) and in the catalytic domain (K529, R530, R532, K535, and K539). To identify whether SPGG variants engage the A3 domain or the catalytic domain or both, we studied β-SPGG-2 and β-SPGG-8 inhibition of recombinant catalytic domain (FXIa-CD) and compared the results to that of the full-length FXIa. The IC50s were measured using chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assay under physiologically relevant conditions (Table 3). CD-FXIa was inhibited by β-SPGG-2 with an IC50 of 1.19 ± 0.08 μg/mL as opposed to 0.80 ± 0.02 μg/mL for the full length FXIa. β-SPGG-8 inhibited CD-FXIa with an IC50 of 0.9 ± 0.1 μg/mL as opposed to 0.15 ± 0.01 μg/mL for the full length FXIa. This suggested that the two SPGG variants bind potently to the catalytic domain alone. Whereas the difference between IC50s is small, or most probably insignificant, for β-SPGG-2, the difference is more substantial for β-SPGG-8. However, even this difference could possibly arise from the difference in glycosylation of the two proteins; human plasma full-length FXIa and recombinant CD-FXIa. Thus, we suggest that SPGG variants primarily target the catalytic domain of FXIa.

Table 3. Inhibition of Full-Length Human Factor XIa and Recombinant Factor XIa Catalytic Domain (CD-FXIa) by β-SPGG-2 and β-SPGG-8 at pH 7.4 and 37 °Ca.

| SPGG variant | FXIa variant | IC50 (μg/mL) | HS | ΔY |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-SPGG-2 (4c) | full-length | 0.80 ± 0.02b | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 100 ± 2 |

| CD-FXIa | 1.19 ± 0.08 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 106 ± 6 | |

| β-SPGG-8 (4f) | full-length | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 97 ± 2 |

| CD-FXIa | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 97 ± 8 | |

IC50, HS, and ΔY values were obtained following nonlinear regression analysis of direct inhibition of human factor XIa, thrombin, and factor Xa in pH 7.4 buffer at 37 °C. Inhibition was monitored by spectrophotometric measurement of the residual enzyme activity. See details under Experimental Procedures.

Errors represent standard error calculated using global fit of the data.

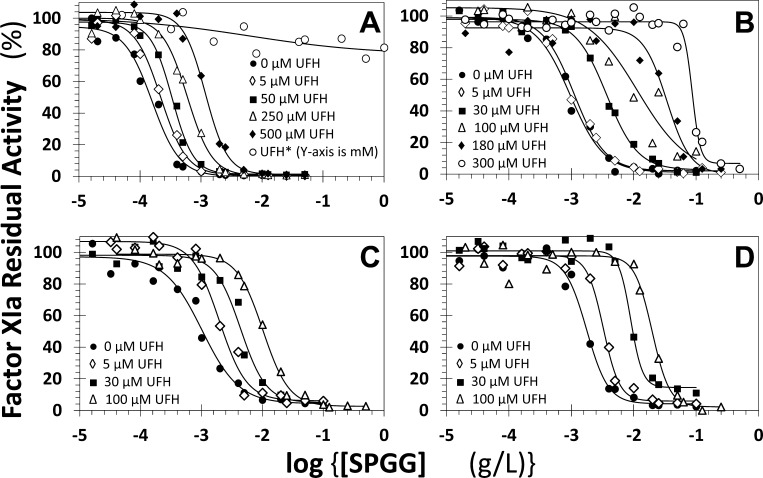

To further assess if the SPGG variants bind close to the heparin-binding site, we measured the IC50s of FXIa inhibition by four SPGG variants in the presence of increasing concentrations of UFH. The logic behind these experiments is that inhibition by SPGG variants should be made more and more dysfunctional as the concentration of UFH increases if the two ligands compete well (the polysaccharide does not inhibit FXIa). Figure 7A shows the change in dose–response profiles of β-SPGG-8 (4f) inhibiting FXIa in the presence of UFH at pH 7.4 and 37 °C. As the concentration of UFH increased from 0 to 500 μM, the IC50 of FXIa inhibition increased from 0.16 to 1.17 μg/mL, a 7.3-fold change. This suggests very weak competition between the two ligands. In contrast, the IC50 of FXIa inhibition by β-SPGG-2 (4c) increased from 0.96 to 86.2 μg/mL, a 86-fold change, as UFH increased from 0 to 300 μM (Figure 7B). This suggested a much more substantial competition between β-SPGG-2 (4c) and UFH (see Supportion Information Table S3). Likewise, there was approximately a 10-fold increase in the IC50 of FXIa inhibition by β-SPGG-0.5 (4a) and β-SPGG-1 (4b) in the presence of only 100 μM UFH (Figure 7C,D). In combination, the results suggest that SPGG variants 4a–4c that are relatively less sulfated than variant 4f compete much better with UFH. Alternatively, less sulfated variants appear to bind to the heparin-binding site on the catalytic domain, whereas the higher sulfated SPGG variant perhaps recognizes anion-binding sites beyond the heparin-binding site on the catalytic domain. This aspect is discussed more in the Conclusions and Significance section.

Figure 7.

Competitive direct inhibition of factor XIa by β-SPGG-8 (4f) (A), β-SPGG-2 (4c) (B), β-SPGG-1 (4b) (C), and β-SPGG-0.5 (4a) (D) in the presence of UFH. The inhibition was determined spectrophotometrically at pH 7.4 and 37 °C. Solid lines represent fits by the dose–response eq 1 to obtain the IC50,predicted, as described in Experimental Procedures. The concentrations of UFH selected for the study are provided.

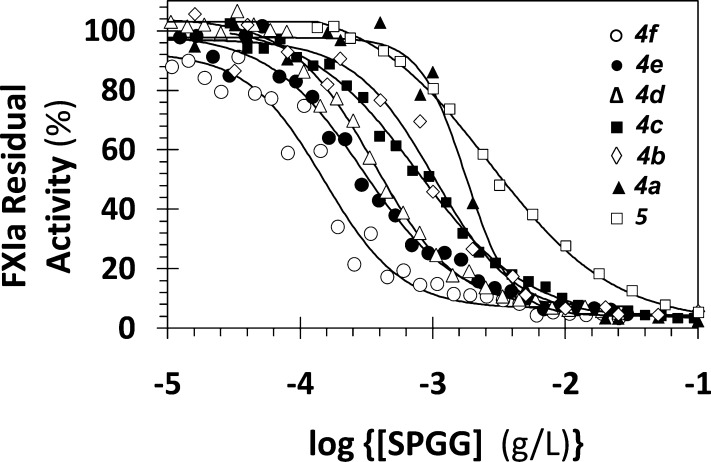

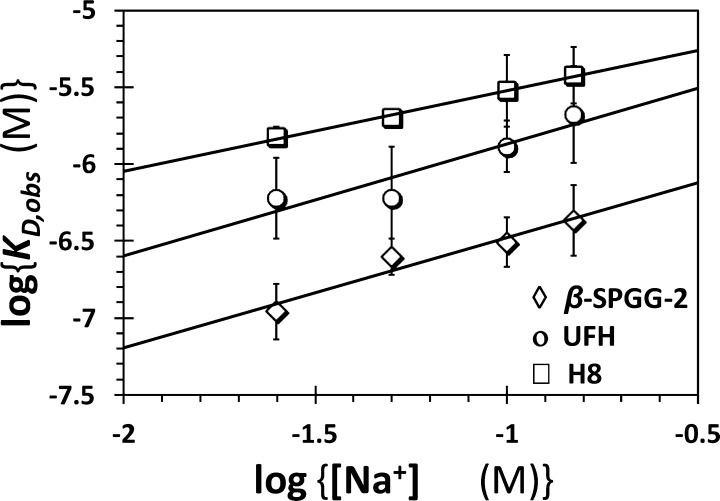

Contribution of Ionic and Nonionic Forces to β-SPGG-2–FXIa Interaction

Although the SPGG–FXIa interaction is likely to be electrostatically driven, nonionic forces may contribute to a significant extent, as noted for heparin–antithrombin interaction.42 A high nonionic binding energy component enhances the specificity of interaction because most nonionic forces, e.g., hydrogen bonding, cation−π interactions, and others depend strongly on the distance and orientation of interacting pair of molecules.47 In comparison, ionic bonds are nondirectional and less dependent on distance, which tends to enhance initial interaction but offer less selectivity of recognition. To determine the nature of interactions between β-SPGG-2 and FXIa, the observed equilibrium dissociation constant (KD,obs) was measured as a function of ionic strength of the medium at pH 7.4 and 37 °C. The KD,obs for β-SPGG-2 binding to DEGR-factor XIa was measured in spectrofluorometric titrations at various salt concentrations, as described above. The KD,obs decreased ∼4-fold from 0.44 ± 0.10 to 0.11 ± 0.02 μM as the salt concentration decreased from 150 to 25 mM (see Table S4 and Figures S4 and S5).

The protein–polyelectrolyte theory42,48 indicates that the contribution of nonionic forces to an interaction, similar to FXIa–SPGG, can be quantified from the intercept of a double log plot (Figure 8). The slope of such a linear profile corresponds to the number of ion-pair interactions (Z) and the fraction of monovalent counterions released per negative charge following ligand binding (Ψ), while the intercepts correspond to the nonionic affinity (KD,NI). β-SPGG-2 exhibited a slope of 0.71 ± 0.13 and intercept of −5.77 ± 0.16 (Table 4). This indicates a binding energy due to ionic forces (ΔG0I) of ∼1.0 kcal/mol at pH 7.4, I 0.15, and a binding energy due to nonionic forces of ∼8.21 kcal/mol (ΔG0NI). Similarly, fluorescence titrations were performed for UFH and H8 interacting with DEGR-FXIa, and the results are presented in Figure 8 and Table 4. The free energies of binding due to ionic forces (ΔG0I) at pH 7.4, I 0.15 were calculated to be 1.03 and 0.75 kcal/mol for UFH and H8, respectively, while the nonionic contribution was 7.38 and 7.08 kcal/mol, respectively (Table 4).

Figure 8.

Dependence of the equilibrium dissociation constant of β-SPGG-2–DEGR-factor XIa complex on the concentration of sodium ion in the medium at pH 7.4 and 37 °C. The KD,obs of β-SPGG-2 (◇), UFH (○), and H8 (□) binding to DEGR-factor XIa was measured through spectrophotometric titrations. Solid lines represent linear regression fits using eq 5. Error bars in symbols represent standard deviation of the mean from at least two experiments. Symbols without apparent error bars indicate that the standard error was smaller than the size of the symbol.

Table 4. Salt Dependence of Affinity Studies for β-SPGG-2, UFH, and H8 at pH 7.4 and 37 °C.

| slopea | Za | intercepta | KD,NI (μM) | ΔG0NI (kcal/mol) | ΔG0NI (%)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-SPGG-2 | 0.71 ± 0.13c | 0.87 ± 0.16 | –5.77 ± 0.16 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 8.2 ± 0.1 | 88.6 |

| UFH | 0.73 ± 0.20 | 0.89 ± 0.24 | –5.14 ± 0.25 | 7.2 ± 0.3 | 7.3 ± 0.03 | 87.4 |

| H8 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 0.64 ± 0.04 | –5.00 ± 0.04 | 10.1 ± 0.4 | 7.1 ± 0.02 | 90.5 |

Slope, Z, and intercept were calculated from linear regressional analysis of log KD,obs versus log[Na] as defined by eq 4.

Nonionic binding energy contribution to the total is expressed as percentage.

Error represent standard error calculated using global fit of the data.

In combination, the results for β-SPGG-2 interacting with FXIa are similar to that for UFH and H8. Although each of these molecules is highly negatively charged, the resolution of the nature of forces involved in recognition shows that nearly 88.6% of binding energy for β-SPGG-2 arises from nonionic forces. The nonionic contribution is 87.4% and 90.5% for UFH and H8, respectively (Table 4). The number of ion-pairs formed in the interaction for β-SPGG-2, UFH, and H8 are 0.875, 0.908, and 0.654, respectively. This suggests that β-SPGG-2 most probably utilizes site(s) on FXIa similar to heparins. β-SPGG-2 is the first small GAG mimetic with such a high nonionic binding energy contribution and may encompass interactions that afford highly selective recognition. The origin of the nonionic interactions is unclear at the present time, however, the majority of forces most probably arise from hydrogen bonds with multiple sulfate groups. It is unlikely that cation−π interactions play any significant role in β-SPGG-2 interactions because such interactions should be nonexistent for UFH and H8, both of which also exhibit high proportion of nonionic contribution.

SPGG Variants Mainly Target the Intrinsic Coagulation Pathway and Do Not Affect the Serpin Pathway of Anticoagulation

Our earlier studies on human plasma anticoagulation indicated that SPGG primarily targets the intrinsic pathway of coagulation, as predicted on the basis of direct FXIa inhibition.37 To assess whether altered sulfation levels modify this property, we measured the prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) of pooled human plasma in the presence of β-SPGG-2 and β-SPGG-8. The concentrations of β-SPGG-2 and β-SPGG-8 required to double APTT were measured to be 49 and 10 μM, respectively (Table 5). In comparison, the PT values were measured to be 152 and 155 μM, respectively, for the two SPGG variants. These results imply that the SPGG variants retain their intrinsic pathway targeting ability, as expected. Furthermore, the 5-fold higher potency of β-SPGG-8 relative to β-SPGG-2 in APTT assay was identical to the difference observed in chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assay.

Table 5. Plasma Clotting Times of Two SPGG Variantsa.

| concentration |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| inhibitor | plasma | test | (μg/mL) | (μM) |

| β-SPGG-2 (4c) | normal | APTT | 96 | 49 |

| PT | 298 | 152 | ||

| β-SPGG-8 (4f) | normal | APTT | 20 | 10 |

| PT | 308 | 155 | ||

| factor XI-deficient | APTT | 77 | 39 | |

| antithrombin-deficient | APTT | 22 | 11 | |

| heparin cofactor II-deficient | APTT | 23 | 12 | |

Prolongation of clotting time as a function of concentration of SPGG variants in either the activated partial thromboplastin time assay (APTT) or the prothrombin time assay (PT). Clotting assays were performed in duplicate (SE ≤ 5%) as described in the Experimental Procedures.

We also used PT and APTT assays to uncover other possible targets of SPGG variants, if any, in exhibiting anticoagulation. In particular, antithrombin and heparin cofactor II are two serpins that have been known to possess heparin binding sites that mediate indirect inhibition of coagulation proteases.42,49 Thus, if SPGG variants exhibit plasma anticoagulation by binding to these serpins, then their absence should increase APTT. A 2-fold increase in APTT required β-SPGG-8 at 11 or 12 μM levels in plasma deficient in antithrombin or heparin cofactor II, respectively (Table 5). This suggests that the anticoagulant potency of β-SPGG-8 remains unaffected by the absence of two key serpins. Yet, a 4-fold increase in β-SPGG-8 levels is necessary to induce anticoagulation in plasma deficient of FXI (Table 5). Thus, the pooled plasma studies indicate that the anticoagulant activity of SPGG variants arises primarily from inhibition of the intrinsic coagulation pathway and does not involve two key heparin-binding serpins.

Conclusions and Significance

Although FXIa is similar to other trypsin-related coagulation enzymes, it is fundamentally different on structural and mechanistic fronts. It functions as a dimer, whereas all other factors function as monomers.50 Additionally, FXI can be activated to FXIa in a stepwise manner with widely different rates of activation,50 suggesting a strong possibility that the two monomers are sampling different conformational states in a dimer. This suggests a fairly high level of cooperativity between the two monomers. The occurrence of such cooperativity is critical for allosteric induction of function/dysfunction. The acylamide quenching studies (Figure 4) support the idea that SPGG variants are able to exploit the dynamics inherent in FXIa to allosterically affect the conformational state of the catalytic domain. Such allosteric modulation bodes well for discovering variable efficacy inhibitors. Although each SPGG variant was found to induce ∼100% inhibition efficacy (Table 1), appropriate structural variation in the scaffold, or pendant groups, may be able to modulate the inherent dynamics so as to induce less than perfect efficacy. A future goal of the program would be to discover variable efficacy modulators rather than inhibitors of FXIa.

The analysis of forces contributing to FXIa–SPGG interaction led to a rather unexpected result. Despite the presence of numerous sulfate groups on a small scaffold, ionic forces were not the dominant contributors. This is in striking contrast to interactions of proteins with natural GAGs, e.g., heparin, that display 40–80% ionic contribution,42,51 and similar to interactions of proteins with aromatic GAG mimetics, e.g., sulfated flavonoids and sulfated lignins.52,53 This work adds to the growing body of evidence that aromatic mimetics of GAGs inherently bind proteins with higher nonionic binding energy, which is expected to induce higher specificity of interaction.

Although we could not prepare per-sulfated variant of SPGG and the difference in the level of sulfation was only about two sulfate groups across the range studied, key results were revealed by studying the eight variants. One, higher levels of sulfation, as with β-SPGG-8, appear to enhance interactions with thrombin and factor Xa, which implies a loss of specificity (probably 2–3-fold). This implies that although the potency against FXIa increases, this may not be desirable. Two, too low a level of sulfation, as with β-SPGG-0.5, is also not desirable because the potency reduces significantly. A moderate level of sulfation, e.g., corresponding to β-SPGG-1 or β-SPGG-2, is likely to exhibit optimal combination of potency and specificity. Compositional profile (Figure 1) reveals that this corresponds to about decasulfated PGG scaffold. Considering anomeric SPGG variants yield identical results, this implies that the presence of 10 sulfate groups on aromatic rings at positions 2 through 6 on the α/β-glucose scaffold. On the basis of results with inhibitor 5, we hypothesize that these 10 sulfate groups could be distributed equally at positions 3 and 5 of the five aromatic rings, as observed earlier on sulfation of the 3,4,5-trihydroxyphenyl scaffold.54,55 This provides an approximate optimal SPGG structure that can be expected to show desired inhibition function without loss of specificity. Yet, this does not imply that all 10 sulfate groups distributed in an essentially symmetric fashion are all important for FXIa recognition. It is more likely that fewer sulfate groups placed at key positions induce allosteric dysfunction of FXIa. In fact, results with inhibitor 5 indicate that a more potent variant is perhaps likely to arise from a slightly different arrangement of sulfate groups. Identification of this SPGG species is important and likely to be challenging. Perhaps advanced studies involving site-directed mutagenesis, X-ray cocrystallography and/or GOLD-based combinatorial virtual library screening of all possible SPGG species binding to FXIa may help identify the best SPGG variant to pursue in preclinical studies.

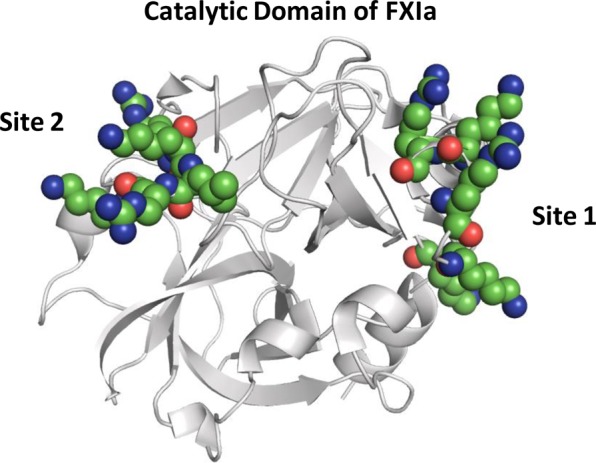

A key result achieved in these studies relates to competitive studies with UFH. Different SPGG variants display different levels of competition with UFH (Figure 7). Whereas effective competition with UFH was apparent for less sulfated variants (β-SPGG-2, −1 and −0.5), the inhibitory effect of β-SPGG-8 could not be displaced with UFH. This suggests significant differences in interactions between SPGG variants. As described in the Introduction, the catalytic domain of FXIa possesses two distinct electropositive sites. Site 1 is the traditional heparin-binding site and consists of residues K529, R530, R532, K536, and K540 (Figure 9).23 This site is approximately 24 Å away from another group of basic residues (R504, K505, R507, and K509), which have been implicated in inhibition mechanism involving serpins.24 Site 1, or the heparin-binding site, is known to be allosterically coupled to the catalytic triad,24 but unambiguous information on such coupling is lacking for site 2. This work suggests that higher sulfated level enhances binding to both sites, presumably simultaneous, and induces allosteric inhibition. In contrast, lower sulfated variants bind preferentially to site 1 only to induce allosteric inhibition. If so, the work suggests that even site 2 is allosterically linked to the catalytic triad in an inhibitory fashion because presence of high levels of UFH, which is expected to compete effectively with the ligand bound at site 1, is not able to reverse inhibition. The results have major implications for clinical relevance and highlight directions to undertake for future SPGG-based allosteric modulators.

Figure 9.

Structure of factor XIa catalytic domain. The crystal structure of factor XIa (PDB ID: 2FDA) shows the presence of two highly electropositive sites that are hypothesized to engage SPGG variants. Site 1 is the traditional heparin-binding site and contains residues K529, R530, R532, K536, and K540, while site 2 is another site containing residues R504, K505, R507, and K509. FXIa is shown in cartoon representation (gray), where the residues in the catalytic domain I and II are shown as spheres colored by atom type.

A final result of considerable clinical value is the discovery that SPGG variants bind to zymogen factor XI with essentially identical affinity as FXIa. Comparison of crystal structures of FXI and FXIa reveals that sites 1 and 2 (above) of the catalytic domain are equally exposed and oriented in both proteins (not shown). This could be the reason for equivalence of affinities of SPGG variants. The results suggest that zymogen FXI could be used to scavenge excessive SPGG from plasma/blood, if needed. This might provide a fine avenue for a simple antidote therapy. Such a tool is expected to be very important for addressing issues observed with the current TSOA therapy.

In conclusion, we have identified important structural constituents that govern selective, allosteric inhibition of FXIa. Our work has led to the discovery that zymogen factor XI could possibly be used as an antidote in a hypothetical anticoagulation therapy with SPGG. The results suggest the possibility that SPGG may recognize more than one anion-binding site on FXIa and highlight directions to undertake in achieving clinical relevance.

Experimental Procedures

Chemicals and Reagents

Organic solvents for synthesis and UPLC analysis were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI) or Fisher (Pittsburgh, PA) and used as such. Chemical reactions sensitive to air or moisture were carried out under nitrogen atmosphere in oven-dried glassware. Reagent solutions, unless otherwise noted, were handled under a nitrogen atmosphere using syringe techniques. n-Hexylamine for ion-pairing UPLC was from Acros Organics (Morris Plains, NJ). Bovine UFH was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). H8 was purchased from V-Laboratories (Covington, LA). 3,4,5-Tribenzyloxybenzoic acid, 3,5-dibenzyloxybenzoic acid, α-d-glucose, β-d-glucose, and α,β-d-glucose were purchased from TCI America (Philadelphia, PA).

Pooled normal human plasma for coagulation assays was purchased from Valley Biomedical (Winchester, VA). Activated partial thromboplastin time reagent containing ellagic acid (APTT-LS), thromboplastin-D, and 25 mM CaCl2 were obtained from Fisher Diagnostics (Middletown, VA). FXI deficient plasma was from Haematologic Technologies (Essex Junction, VT), whereas antithrombin and heparin cofactor II deficient plasmas were from Affinity Biologicals Inc. (Ancaster, ON).

Proteins and Chromogenic Substrates

Human plasma proteins including thrombin, factors Xa, XIa, FXIa-DEGR, and XI were obtained from Haematologic Technologies (Essex Junction, VT). Stock solutions of factors XIa, XI, and thrombin were prepared in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% PEG8000, and 0.02% Tween80. Stock solution of factor Xa was prepared in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 100 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 0.1% PEG8000, and 0.02% Tween80. Chromogenic substrates including Spectrozyme TH (H-d-cyclohexylalanyl-Ala-Arg-p-nitroanilide) and Spectrozyme factor Xa (methoxycarbonyl-d-cyclohexylglycyl-Gly-Arg-p-nitroanilide) were obtained from American Diagnostica (Greenwich, CT). S-2366 (l-PyroGlu-Pro-Arg-p-nitroaniline HCl) was obtained from Diapharma (West Chester, OH). FXIa-CD was a gift from Dr. Alireza Rezaie of Saint Louis University.

Chromatography and Spectroscopic Analysis

Analytical TLC was performed using UNIPLATE silica gel GHLF 250 μ precoated plates (ANALTECH, Newark, DE). Flash chromatography was performed using Teledyne ISCO Combiflash RF system (Lincoln, NE) and disposable normal phase silica cartridges of 30–50 μ particle size, 230–400 mesh size, and 60 Å pore size. The mobile phase gradients in flash chromatography used hexanes/EtOAc and CH2Cl2/CH3OH mixtures for resolving unsulfated precursors. Sulfated derivatives were purified using Sephadex G10 size exclusion chromatography with deionized water as the mobile phase. The quaternary ammonium counterion of sulfate moieties was exchanged for sodium ion using SP Sephadex-Na cation exchange chromatography. Regeneration of the cation exchange column was performed with 500 mL of 2 M NaCl solution.

Each compound was characterized using 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, which was performed using Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer in either CDCl3, acetone-d6, or D2O. Signals (in ppm) are either relative to the internal standard (tetramethyl silane, TMS) or to the residual peak of the solvent. The NMR data are reported as chemical shift (ppm), multiplicity of signal (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, dd = doublet of doublet, m = multiplet), coupling constants (Hz), and integration. ESI-MS profiles were recorded using Waters Acquity TQD MS spectrometer in positive or negative ion mode. Samples were dissolved in acetonitrile or water and infused at a rate of 20–100 μL/min. Mass scans were obtained, as reported earlier.37 Briefly, for unsulfated intermediates, mass scans were obtained in the range of 200–700 amu with a scan time of 1 s. Ionization conditions (capillary voltage = 3–4 kV, cone voltage = 30–230 V , extractor voltage = 3 V, Rf lens voltage = 0.1 V, source block temperature = 150 °C, desolvation temperature = ∼250 °C) were optimized for each compound to maximize parent ion signal. For the sulfated products, a Waters Acquity H-class UPLC system equipped with a photodiode array detector and TQD MS was used. A reversed-phase Waters BEH C18 column of particle size 1.7 μm and 2.1 mm × 50 mm dimensions at 30 ± 2 °C was used for resolving components. Solvent A consisted of 25 mM n-hexylamine in water containing 0.1% (v/v) formic acid, while solvent B consisted of 25 mM n-hexylamine in acetonitrile–water mixture (3:1 v/v) containing 0.1% (v/v) formic acid. Resolution of each SPGG variant into distinct peaks was achieved with a flow rate of 500 μL/min and a linear gradient of 3% solvent B per min over 20 min starting with an initial composition of 20% (v/v) solvent B. The sample was first detected by UV absorbance in the range of 190–400 nm and then by ESI-MS in positive ion mode (capillary voltage = 4 kV, cone voltage = 20 V, desolvation temperature = 350 °C, nitrogen gas flow = 650 L/h). Mass scans were collected multiple times in the range of 1000–2048 amu within 0.25 s and coadded to enhance signal-to-noise ratio. On the basis of the UPLC-ESI-MS profiles, the purity of the synthesized SPGG variants was found to be greater than 95%.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of SPGG Variants

The synthesis of SPGG variants was achieved by chemical sulfation of pentagalloyl-d-glucopyranoside anomeric derivatives (β-PGG (3a), α-PGG (3b), or their natural mixture (3c)) (see Scheme 1). The synthesis of the precursors 3a, 3b, or 3c was achieved in two steps: DCC-mediated esterification with 3,4,5-tribenzyloxybenzoic acid and palladium-catalyzed per-debenzylation, from either α-glucose or β-glucose (or their natural mixture), respectively, following methods reported in the literature (see Supporting Information).40 Eight variants of SPGG (Scheme 1), labeled as β-SPGG-0.5 (4a), β-SPGG-1 (4b), β-SPGG-2 (4c), β-SPGG-4 (4d), β-SPGG-6 (4e), β-SPGG-8 (4f), α-SPGG-8 (4g), and α,β-SPGG (4h), were quantitatively synthesized following the protocol of microwave-assisted sulfation with N(CH3)3:SO3 complex, reported earlier for nonsaccharide GAG mimetics,37,54,55 except for varying the reaction time from 0.5 to 8 h, as denoted by the number following the SPGG label. These derivatives were characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and UPLC-MS, as described earlier.37 The UPLC profile of the derivatives in combination with MS identification of component masses was used to calculate the average molecular weights of the SPGG variants (see Supporting Information Table S1 and Figures S1 and S2). On the basis of the UPLC-ESI-MS profile, SPGG variants do not contain any species other than the sulfated PGG species. Thus, the purity of these variants is estimated to be higher than 95%. Similar procedure was used to synthesize the decasulfated derivative 5.

Direct Inhibition Studies

Direct inhibition of the desired enzyme by 4a–4h and 5 was measured using a chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assay on a microplate reader (FlexStation III, Molecular Devices), as reported earlier.37 Briefly, to each well of a 96-well microplate containing 85 or 185 μL of 20–50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 100–150 mM NaCl, 0.1% PEG8000, and 0.02% Tween80 at either 37 °C (factors XIa and Xa) or 25 °C (thrombin) was added 5 μL of SPGG variant (or vehicle) and 5 μL of the enzyme. The final concentrations of the enzymes were 0.765 nM (FXIa), 6 nM (thrombin), and 1.09 nM (factor Xa). After 10 min incubation, 5 μL of 6.9 mM S-2366 or 1.0 mM Spectrozyme TH or 2.5 mM Spectrozyme FXa, was rapidly added and the residual enzyme activity was measured from the initial rate of increase in A405. Relative residual enzyme activity (Y, activity in the presence of inhibitor to that in its absence) as a function of the concentration of SPGG variant was fitted using logistic eq 1 to obtain the potency (IC50), efficacy (ΔY = YM – Y0) and Hill slope (HS) of inhibition. In this equation, YM and Y0 are the maximal and minimal values of Y.

| 1 |

Michaelis–Menten Kinetics of S-2366 Hydrolysis by FXIa in the Presence of β-SPGG-8 (4f)

The initial rate of S-2366 hydrolysis by 0.765 nM FXIa was obtained from the linear increase in A405 corresponding to less than 10% consumption of the substrate. The initial rate was measured at various S-2366 concentrations (0.01–2.0 mM) in the presence of fixed concentrations of β-SPGG-8 (4f) in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% PEG8000, and 0.02% Tween80 at 37 °C. The data was fitted using the standard Michaelis–Menten to determine the KM and VMAX of catalysis.

Inhibition of FXIa by SPGG Variants in the Presence of UFH

Inhibition of FXIa by SPGG variants 4a, 4b, 4c, or 4f was performed in the presence of UFH using the 96-well microplate format. A 5 μL solution of SPGG variant (0–10 mg/mL) and 5 μL of FXIa (0.765 nM final concentration) with 5 μL of UFH (0–500 μM) in 80 μL 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% PEG8000 was incubated at 37 °C for 5 min followed by addition of 5 μL of 6.9 mM S-2366. The initial rate of substrate hydrolysis was measured from the change in A405, and the IC50 was calculated using eq 1.

Quenching of DEGR-FXIa Fluorescence with Acrylamide

Acrylamide quenching of DEGR-FXIa fluorescence was studied in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% PEG8000 at 37 °C. Fluorescence emission of DEGR-FXIa at 547 nm (λEX = 345 nm) was measured in the absence and presence of 20 μM β-SPGG-8 (4c) or 20 μM UFH following the addition of increasing concentrations of the quencher (Q) acrylamide (0–0.6 M). The excitation and emission slits were set to 1.0 and 1.5 mm, respectively. Quenching of the DEGR-FXIa fluorescence intensity was fitted using the classic linear Stern–Volmer eq 2 or its quadratic derivative eq 3, as described by Lakowicz.56 In these equations, F0 and F are the fluorescence intensities in the absence and presence of the quencher, respectively, and K1 and K2 are two different Stern–Volmer constants for fluorophores present in DEGR-FXIa.

| 2 |

or

| 3 |

Fluorescence Spectroscopy-Based Measurement of the Binding Affinity

Fluorescence experiments were performed using a QM4 spectrofluorometer (Photon Technology International, Birmingham, NJ) in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% PEG8000 at 37 °C. The affinity of FXIa, factor XI or DEGR-FXIa for either SPGG variants, UFH or H8, was measured using either the change in the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (λEM =340 nm, λEX = 280 nm) or dansyl fluorescence (λEM = 547 nm, λEX = 345 nm) at varying concentrations of the ligand (L). The titrations were performed by adding aliquots of 200–250 μM aqueous solution of β-SPGG-2 (4c), β-SPGG-8 (4f), UFH, or H8 to 105 nM FXIa or FXI, or 250 nM DEGR-FXIa and monitoring the fluorescence intensity at the appropriate λEM. The excitation and emission slits were set to 1.0 and 1.5 mm, respectively. The observed change in fluorescence (ΔF) relative to initial fluorescence (F0) was fitted using eq 4 to obtain the dissociation constant (KD) and the maximal change in fluorescence (ΔFMAX) at saturation. Fluorescence emission spectra of DEGR-FXIa (250 nM) in the absence and presence of 20 μM β-SPGG-2 (4c), 20 μM UFH, or 20 μM H8 were also recorded using λEX of 345 nm. The λEM was scanned from 350–600 nm in increments of 1 nm. The excitation and emission slit widths were set at 1.0 and 1.5 mm, respectively.

| 4 |

Salt Dependence of Affinity of DEGR-FXIa for β-SPGG-2 (4c), UFH, and H8

The affinities of DEGR-FXIa for β-SPGG-2 (4c), UFH, and H8 were measured using the change in the fluorescence of the active site dansyl group, as described above, at 37 °C in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.1% PEG8000 and varying salt concentration (25, 50, 100, and 150 mM NaCl). Titrations were performed by adding aliquots of a solution of β-SPGG-2 (4c) (35–95 μM), UFH (50 μM), or H8 (50 μM) to a fixed concentration of DEGR-FXIa (250 nM) and using eq 4 to calculate the KD. The contributions of ionic and nonionic binding energies to the interactions were obtained from slope and intercept of the linear plot of log KD,obs versus log [Na+], according to eq 5. In this equation, KD,NI is the dissociation constant at [Na+] = 1 M and slope “m” = Z × Ψ, where Z is the number of ion-pairs formed upon binding and Ψ is the fraction of monovalent counterions released per negative charge following interaction.42

| 5 |

Effects of SPGG Variants on the PT and APTT of Pooled Human Plasmas

The effect of two SPGG variants (4c and 4f) on human plasma clotting was measured in a standard one-stage recalcification assay with a BBL Fibrosystem fibrometer (Becton-Dickinson, Sparles, MD), as described previously.37 For prothrombin time (PT) assays, thromboplastin-D was reconstituted according to the manufacturer’s directions and warmed to 37 °C. Then 10 μL of the SPGG variant solution, to give the desired concentration, was brought up to 100 μL with citrated human plasma, incubated for 30 s at 37 °C, followed by addition of 200 μL of prewarmed thromboplastin-D, and time to clot was meausred. For the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) assay, 10 μL of SPGG solution was mixed with 90 μL of citrated human plasma and 100 μL of prewarmed APTT reagent (0.2% ellagic acid). After incubation for 4 min at 37 °C, clotting was initiated by adding 100 μL of prewarmed 25 mM CaCl2 and time to clot was determined. The data were fit to a quadratic trend line, which was used to determine the concentration of the inhibitor necessary to double the clotting time. Effect of β-SPGG-8 (4f) on APTT using FXIa-deficient human plasma, antithrombin-deficient human plasma, or heparin cofactor II-deficient human plasma was studied in a similar fashion. Clotting time in the absence of an anticoagulant was determined in a similar fashion using 10 μL of deionized water and was found to be 18.5 s for PT and 42.5 s for APTT in case of normal human plasma, 31.5 s for APTT using antithrombin-deficient plasma, 35.7 s for APTT using heparin cofactor II-deficient plasma, and 140 s for APTT using FXIa-deficient plasma.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Nehru Viji S. and Akul Y. Mehta of VCU for preparing Figure 9 and performing UPLC-MS experiments, respectively. This work was supported by grants HL090586 and HL107152 from the National Institutes of Health to U.R.D. and a Mid-Atlantic Affiliate postdoctoral fellowship to R.A.A.-H. from the American Heart Association (grant 12POST10930004).

Glossary

Abbreviations Used

- APTT

activated partial thromboplastin time

- FXIa-CD

catalytic domain of factor XIa

- DEGR-FXIa

DEGR-labeled factor XIa

- FXIa-WT

the wild-type factor XIa

- GAG

glycosaminoglycan

- H8

heparin octasaccharide

- HBS

heparin-binding site

- PGG

penta-galloylglucoside

- QAO

quinazolinone

- SPGG

sulfated penta-galloylglucoside

- UFH

unfractionated heparin

- TSOA

target-specific oral anticoagulants

- VTE

venous thromboembolism

Supporting Information Available

General procedures for chemical synthesis (esterification, deprotection, and sulfation) as well as the characterization data for molecules 4a, 4b, 4c, 4f, 2d, 3d, and 5. Representative UPLC profiles, salt dependent studies, and all fluorescence spectroscopy experiments. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

R.A.A.-H. performed all the studies and prepared the initial draft of manuscript; U.R.D. supervised the study and finalized the paper.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Ruppert A.; Lees M.; Steinle T. Clinical burden of venous thromboembolism. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2010, 26, 2465–2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutescu E. A.; Dager W. E.; Kalus J. S.; Lewin J. J. III; Cipolle M. D. Management of bleeding and reversal strategies for oral anticoagulants: clinical practice considerations. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2013, 70, 1914–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cove C. L.; Hylek E. M. An updated review of target-specific oral anticoagulants used in stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation, venous thromboembolic disease, and acute coronary syndromes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2013, 2, e000136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates S.; Sarode R. Novel thrombin and factor Xa inhibitors: challenges to reversal of their anticoagulation effects. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2013, 20, 552–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Montfoort M. L.; Meijers J. C. M. Anticoagulation beyond direct thrombin and factor Xa inhibitors: indications for targeting the intrinsic pathway?. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 110, 223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girolami A.; Ruzzon E.; Tezza F.; Scandellari R.; Vettore S.; Girolami B. Arterial and venous thrombosis in rare congenital bleeding disorders: a critical review. Haemophilia 2006, 12, 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon O.; Steinberg D. M.; Koren-Morag N.; Tanne D.; Seligsohn U. Reduced incidence of ischemic stroke in patients with severe factor XI deficiency. Blood 2008, 111, 4113–4117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwenberg E. C.; Meijers J. C. M.; Monia B. P.; Levi M. Coagulation factor XI as a novel target for antithrombotic treatment. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 8, 2349–2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligsohn U. FXI deficiency in humans. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2009, 7, 84–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusga S.; Salomon O. Factor XI deficiency. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2009, 35, 416–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez K.; Bolton-Maggs P. Factor XI deficiency. Haemophilia 2008, 14, 1183–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen E. D.; Gailani D.; Castellino F. J. FXI is essential for thrombus formation following FeCl3-induced injury of the carotid artery in the mouse. Thromb. Haemost. 2002, 87, 774–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Smith P. L.; Hsu M. Y.; Gailani D.; Schumacher W. A.; Ogletree M. L.; Seiffert D. A. Effects of factor XI deficiency on ferric chloride induced vena cava thrombosis in mice. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006, 4, 1982–1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Cheng Q.; Xu L.; Feuerstein G. Z.; Hsu M. Y.; Smith P. L.; Seiffert D. A.; Schumacher W. A.; Ogletree M. L.; Gailani D. Effects of factor IX or factor XI deficiency on ferric chloride-induced carotid artery occlusion in mice. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005, 3, 695–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber A.; Hanson S. R. Factor XI-dependence of surface- and tissue factor-initiated thrombus propagation in primates. Blood 2003, 102, 953–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker E. I.; Marzec U. M.; White T. C.; Hurst S.; Rugonyi S.; Mccarty O. J.; Gailani D.; Gruber A.; Hanson S. R. Prevention of vascular graft occlusion and thrombus-associated thrombin generation by inhibition of factor XI. Blood 2009, 113, 936–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita A.; Nishihira K.; Kitazawa T.; Yoshihashi K.; Soeda T.; Esaki K.; Imamura T.; Hattori K.; Asada Y. Factor XI contributes to thrombus propagation on injured neointima of the rabbit iliac artery. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006, 4, 1496–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher W. A.; Seiler S. E.; Steinbacher T. E.; Stewart A. B.; Bostwick J. S.; Hartl K. S.; Liu E. C.; Ogletree M. L. Antithrombotic and hemostatic effects of a small molecule factor XIa inhibitor in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 570, 167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gailani D.; Smith S. B. Structural and functional features of factor XI. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2009, 7, 75–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley J.; McEwan P. A.; Gailani D. Structure and function of factor XI. Blood 2010, 115, 2569–2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho D. H.; Badellino K.; Baglia F. A.; Walsh P. N. A binding site for heparin in the apple 3 domain of factor XI. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 16382–16390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M.; Abdel-Razek T.; Sun M. F.; Gailani D. Characterization of a heparin-binding site on the heavy chain of factor XI. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 31153–31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badellino K. O.; Walsh P. N. Localization of a heparin binding site in the catalytic domain of FXIa. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 7569–7580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Sun M. F.; Gailani D.; Rezaie A. R. Characterization of a heparin-binding site on the catalytic domain of factor XIa: mechanism of heparin acceleration of factor XIa inhibition by the serpins antithrombin and C1-inhibitor. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 1517–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. H.; Smith S. A.; Morrissey J. H. Polyphosphate is a cofactor for the activation of factor XI by thrombin. Blood 2011, 118, 6963–6970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha D.; Badellino K. O.; Marcinkiewicz M.; Walsh P. N. Allosteric modification of factor XIa functional activity upon binding to polyanions. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 7593–7600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai U. R. The promise of sulfated synthetic small molecules as modulators of glycosaminoglycan function. Future Med. Chem. 2013, 5, 1363–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu P. S.; Abdel Aziz M. H.; Sarkar A.; Mehta A. Y.; Zhou Q.; Desai U. R. Designing allosteric regulators of thrombin. Exosite 2 features multiple subsites that can be targeted by sulfated small molecules for inducing inhibition. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 5059–5070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu P. S.; Liang A.; Mehta A. Y.; Abdel Aziz M. H.; Zhou Q.; Desai U. R. Rational design of potent, small, synthetic allosteric inhibitors of thrombin. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 5522–5531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanessian S.; Larsson A.; Fex T.; Knecht W.; Blomberg N. Design and synthesis of macrocyclic indoles targeting blood coagulation cascade Factor XIa. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 6925–6928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.; Deng H.; Jin L.; Pandey P.; Quinn J.; Cantin S.; Rynkiewicz M. J.; Gorga J. C.; Bibbins F.; Celatka C. A.; Nagafuji P.; Bannister T. D.; Meyers H. V.; Babine R. E.; Hayward N. J.; Weaver D.; Benjamin H.; Stassen F.; Abdel-Meguid S. S.; Strickler J. E. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of peptidomimetic inhibitors of fXIa as novel anticoagulants. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 7781–7791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H.; Bannister T. D.; Jin L.; Babine R. E.; Quinn J.; Nagafuji P.; Celatka C. A.; Lin J.; Lazarova T. I.; Rynkiewicz M. J.; Bibbins F.; Pandey P.; Gorga J.; Meyers H. V.; Abdel-Meguid S. S.; Strickler J. E. Synthesis, SAR exploration, and X-ray crystal structures of factor XIa inhibitors containing an α-keto-thiazole arginine. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 3049–3054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher W. A.; Seiler S. E.; Steinbacher T. E.; Stewart A. B.; Bostwick J. S.; Hartl K. S.; Liu E. C.; Ogletree M. L. Antithrombotic and hemostatic effects of a small molecule factor XIa inhibitor in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 570, 167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarova T. I.; Jin L.; Rynkiewicz M.; Gorga J. C.; Bibbins F.; Meyers H. V.; Babine R.; Strickler J. Synthesis and in vitro biological evaluation of arylboronic acids as potential inhibitors of factor XIa. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 5022–5027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan M. S.; Carroll A. R.; Wessling D.; Jobling M.; Avery V. M.; Davis R. A.; Feng Y.; Xue Y.; Oster L.; Fex T.; Deinum J.; Hooper J. N.; Quinn R. J. Clavatadine A, a natural product with selective recognition and irreversible inhibition of factor XIa. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 3583–3587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan M. L.; Wong P. C.; Wang C.; Woerner F.; Smallheer J. M.; Barbera F. A.; Bozarth J. M.; Brown R. L.; Harpel M. R.; Luettgen J. M.; Morin P. E.; Peterson T.; Ramamurthy V.; Rendina A. R.; Rossi K. A.; Watson C. A.; Wei A.; Zhang G.; Seiffert D.; Wexler R. R. Tetrahydroquinoline derivatives as potent and selective factor XIa inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 955–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Horani R. A.; Ponnusamy P.; Mehta A. Y.; Gailani D.; Desai U. R. Sulfated pentagalloyl-glucoside is a potent, allosteric, and selective inhibitor of factor XIa. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 867–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karuturi R.; Al-Horani R. A.; Mehta S. C.; Gailani D.; Desai U. R. Discovery of allosteric modulators of factor XIa by targeting hydrophobic domains adjacent to its heparin-binding site. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 2415–2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argade M. D.; Mehta A. Y.; Sarkar A.; Desai U. R. Allosteric inhibition of human factor XIa: Discovery of monosulfated benzofurans as a class of promising inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 3559–3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanbabaee K.; Lötzerich K. Efficient total synthesis of the natural products 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-galloyl-d-glucopyranose, 1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-galloyl-β-d-glucopyranose and the unnatural 1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-galloyl-α-d-glucopyranose. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 10725–10732. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.-C.; Prusoff W. H. Relationship between the inhibition constant (KI) and the concentration of the inhibitor which causes 50% inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973, 22, 3099–3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai U. R.; Petitou M.; Björk I.; Olson S. T. Mechanism of heparin activation of antithrombin. Role of individual residues of the pentasaccharide activating sequence in the recognition of native and activated states of antithrombin. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 7478–7487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry B. L.; Abdel Aziz M.; Zhou Q.; Desai U. R. Sulfated, low-molecular-weight lignins are potent inhibitors of plasmin, in addition to thrombin and factor Xa: novel opportunity for controlling complex pathologies. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 103, 507–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai B. J.; Boothello R.; Mehta A. Y.; Scarsdale J. N.; Wright H. T.; Desai U. R. Interaction of thrombin with sucrose octasulfate. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 6973–6982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Horani R. A.; Liang A.; Desai U. R. Designing nonsaccharide allosteric activators of antithrombin for accelerated inhibition of factor Xa. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 6125–6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y.; Verhamme I. M.; Smith S. A.; Cheng Q.; Sun M. F.; Sheehan J. P.; Morrissey J. H.; Gailani D. Factor XI anion-binding sites are required for productive interactions with polyphosphate. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 11, 2020–2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosier P. D.; Krishnasamy C.; Kellogg G. E.; Desai U. R. On the specificity of heparin/heparan sulfate binding to proteins. Anion-binding sites on antithrombin and thrombin are fundamentally different. PLoS One 2012, 7, e48632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascotti D. P.; Lohman T. M. Thermodynamics of charged oligopeptide–heparin interactions. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 2908–2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefsen D. M. Heparin cofactor II. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1997, 425, 35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y.; Verhamme I. M.; Smith S. B.; Sun M. F.; Matafonov A.; Cheng Q.; Smith S. A.; Morrisey J. H.; Gailani D. The dimeric structure of factor XI and zymogen activation. Blood 2013, 121, 3962–3969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]