Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV), which describes physical and/or sexual assault of a spouse or sexually intimate companion, is a common health care issue across the globe. However, existing health outcomes studies are limited. Additionally, no study to our knowledge has specifically focused on the relationship between IPV and sexual health among Latina immigrants in southwestern United States. Through the use of photovoice methodology and a community-based participatory research approach, we assessed these types of relationships drawing on data gathered from 22 Latina survivors of IPV and 20 community stakeholders in El Paso, Texas. Participants identified two major themes: the different expressions of domestic violence and the need for access to sexual and reproductive health services. Community stakeholders and participants identified practical and achievable recommendations and actions including the development of a promotora training program on IPV and sexual health. This assessment extends beyond HIV and STI risk behaviors and highlights disease prevention within a wellness and health promotion framework.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, Latinas, immigrants, border health, photovoice methodology, sexual and reproductive health

Introduction

This article explores the use of photovoice methodology and community-based participatory research approaches to assess the relationship between intimate partner violence (IPV) and sexual health among Latina immigrants in southwestern United States. Although IPV cuts across sociodemographic categories such as class, race/ethnicity, gender, and culture, Latinas are disproportionately affected by this problem (Breiding, Black, & Ryan, 2008; Fedovskiy, Higgins, & Paranjape, 2008; González-Guarda, Vasquez, Urrutia, Villarruel, & Peragallo, 2011; Moynihan, Gaboury, & Onken, 2008; Raj & Silverman, 2002; Tjaden, 2000). IPV is a widespread public health concern that has been associated with myriad negative physical and mental health consequences (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2010; Valentine, Rodriguez, Lapeyrouse, & Muyu, 2011). For example, battered Latinas are at higher risk for depression, suicide, posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol/drug abuse or dependence, and poor physical health relative to women in non-abusive relationships (Fedovskiy et al., 2008; Golding, 1999; González-Guarda, Peragallo, Vasquez, Urrutia, & Mitrani, 2009). Pregnant Latinas are even more disproportionally affected by IPV. A 2008 study found that 92 of 210 pregnant Latinas studied over the course of 1 year reported intimate partner abuse. Social support was lower for the 92 abused women, who also reported higher levels of stress coupled with social undermining by their partners. As expected, pregnant Latinas who were exposed to abuse were more likely to be depressed (41.3%) or have posttraumatic stress disorder (16.3%) than their nonabused counterparts (18.6% and 7.6%, respectively; Rodriguez et al., 2008).

National data are scarce, but a number of small-scale, community-based studies indicate that IPV is an important cause of morbidity and mortality (Abbott, 1997; Crandall, Schwab, Sheehan, & Esposito, 2009; Gilbert, El-Bassel, Chang, Wu, & Roy, 2012) and is an important factor affecting women's sexual and reproductive health (Heise, Ellsberg, & Gottemoeller, 1999; Rahman, Nakamura, Seino, & Kizuki, 2012; Sarkar, 2008). Some forms of IPV include sexual coercion and unwanted sexual contact. Forced sex is associated with a range of gynecological and reproductive health problems, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), unwanted pregnancy, vaginal bleeding or infection, fibroids, decreased sexual desire, genital irritation, pain during intercourse, chronic pelvic pain, and urinary tract infections (Kishor, 2012; Maman, Campbell, Sweat, & Gielen, 2000; Schafer et al., 2012). Studies have also documented that violence greatly limits married women's ability to use contraceptives and other health services and resources, including HIV- and STI-screening venues (Cho & Kim, 2012; Guruge & Humphreys, 2009; McCarraher, Martin, & Bailey, 2006).

Photovoice methodology has been used to address complex health issues affecting Latinas. However, little is known about the potential of the photovoice method to help understand IPV and its effects on sexual health specifically among Latinas in southwestern United States. This methodology uses photography and group dialogue as a means for marginalized and vulnerable individuals to deepen their understanding of a community issue or concern (e.g., IPV and sexual and reproductive health). Photovoice is indebted to theoretical literatures focusing on education and critical consciousness, feminist theory, action research, and nontraditional approaches to documentary photography (Catalani & Minkler, 2010). Photovoice serves as a means to empower participants to record and reflect on their situation from their own perspectives, thus promoting critical dialogue and knowledge about individuals and community issues. The ultimate aim of this method is to trigger social change through group discussions capable of influencing policy and decision makers. Instead of being passive in the research process, participants become actively engaged in recording their own experiences as coresearchers who collect data, frame discussions, and conduct the analysis.

This study took place in the U.S.–Mexico border region, a distinct geographic, economic, cultural, and social area. The social and economic problems of the border region include poverty, health disparities, social inequalities, low-wage assembly jobs, and irregular agricultural and seasonal employment (Lusk, Staudt, & Moya, 2012). The border between the United States and Mexico is 1,993 miles long, and U.S.–Mexico border crossings are among the busiest in the world (Mendoza, Ruiz, & Escárzaga, & Ford, 2002). El Paso, Texas, shares a border with Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua. El Paso is the fourth largest city in Texas, with a population of 800,647. Over 80% of El Paso residents are Hispanic, (primarily of Mexican and Mexican American origin), part of the largest minority group in the United States, with three quarters of the population of El Paso speaking a language other than English at home. The annual median household income is $36,078 (Newswire, 2011; Rahman et al., 2012).

Poverty, coupled with the lack of health insurance, makes it difficult for individuals in the area to access sexual and reproductive health services (Deusdad-Ayala, Moya, & Chavez-Baray, 2012; McGuire, 1985). In addition, Texas ranks last in the United States in prenatal care during the first trimester of pregnancy (Kishor, 2012), and family planning clinics in Texas serve only 32% of women in need of contraceptive services (Schafer et al., 2012). Furthermore, mental health services in the border region lag behind the nation. Although the border is a minority-majority region, minorities have less access to physical and mental health services. The situation is aggravated by a difference in the type of treatment individuals from different ethnic groups receive (Villalobos & Islas, 2012).

Research on the incidence and prevalence of IPV among Latinas in El Paso, Texas, is scant at best. Thus, there is a dire need to collect comprehensive behavioral data on cases involving IPV and family violence in the region. Border communities remain beyond the scope of national and state efforts regarding issues of IPV (Rocha, Mata, Tyroch, McLean, & Blough, 2006). Our study responds to this need by presenting and analyzing data on survivors of IPV while providing policy recommendations to implement public health initiatives at the local, state, and national levels that will be particularly beneficial to vulnerable women in border communities.

Method

Photovoice Method

We applied the photovoice method to collect data presented in this study. This method uses five key concepts: (a) images provide both insight and a learning opportunity, which in turn influence individuals' health and well-being; (b) images affect policy by influencing the way we look at the world and the way we see ourselves and therefore have the potential to influence decision makers and the broader society as well; (c) individual community members should actively participate in creating and defining the images that shape public health policy; (d) the involvement of policy and decision makers, and particularly community stakeholders who can affect change, from the beginning of a study is central to the study's success; and (e) both individual and community advocacy efforts aimed at mobilizing and empowering participants are required to effect social change (Garcia et al., 2013; Wang & Burris, 1997).

Establishing Relationships With Community Stakeholders

We also used community-based participatory research approaches to guide our study. This project represents an example of a creative, resourceful, and interdisciplinary partnership of community members and academicians committed to improving the quality of life of women and families. The study builds on the long-standing collaboration between academic institutions, community-based organizations, and governmental agencies, comprising the University of Texas at El Paso, the Ventanilla de Salud of the General Mexican Consulate in El Paso, the Programa Compañeros in Ciudad Juarez, the Public Health Department of the City of El Paso, the Diocesan Migrant and Refugee Services, the University Centennial Museum and Gardens, Familias Triunfadoras, and the Fiscalia Especializada en Atención a Victimas y Ofendidos del Delito en Chihuahua (Crime Victims Unit of the State of Chihuahua Mexico). As a result of this project, we expanded our collaboration with other agencies and research institutions such as the HIV Center at Columbia University, Indiana University–Bloomington, the Center Against Family Violence, Paso del Norte Health Foundation, and Centro de Crisis Casa Amiga in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Furthermore, an advisory committee consisting of 20 community and academic members was formed in the early stages of the study to assist with the project development and dissemination of findings.

Sampling and Recruitment

Study participants comprised a convenience sample of 22 Mexican migrant women who were victims/survivors of IPV. Demographic characteristics can be found in Table 1. The principal investigator (PI) and study director recruited participants from two community-based agencies serving the needs of Latinas affected by IPV (the Diocesan Migrant and Refugee Services and Familias Triunfadoras). Inclusion criteria included being a Latina, Spanish-speaking, and victim/survivor of IPV.

TABLE 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Group 1 | Group 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants | 11 | 11 | |

| Ethnicity | Mexican-origin migrants | Mexican-origin migrants | |

| Domestic violence experience (%) | 100 | 100 | |

| Age range (average), years | 16a–50 (38) | 19–72 (45.5) | |

| Years of formal education (average) | 9–20 (14.6) | 6–17 (11.5) | |

| Health insurance (type) | 1 (private plan) | 2 (Medicaid) | |

| Occupation | 3 | Domestic work | 0 |

| 2 | Service industry | 1 | |

| 6 | Professional | 3 | |

| 1 | Student | 3 | |

| 1 | Unemployed | 9 | |

| 0 | Volunteer promotora (community health worker) | 6 | |

Daughter of one of the participants. We received parental consent.

Public health literature technically defines domestic violence as violent acts perpetrated by a family member against another family member, most often referring to women's experience of violence by an intimate partner. For the purpose of this study we operationalized IPV as follows: any act of gender-based violence perpetrated against a partner in an intimate relationship that resulted in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion, or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2010).

Thirty-two women met the inclusion criteria and were invited to participate; 25 attended the initial orientation, and 22 women agreed to participate, eventually completing the photovoice project. Three participants did not complete the phtotovoice process due to work commitments and personal obligations. Participants received an incentive of US$10 and educational materials (e.g., T-shirts, stress balls, brochures, and health materials) for each session.

Procedures

The institutional review board of the University of Texas at El Paso approved the study. A signed consent form was obtained from each participant, with a copy of the signed form provided to each individual. Each participant received information on the risks and benefits associated with participating in the project. Study procedures included conducting photovoice training, facilitation, themes selection, and data analysis.

Conducting Photovoice Training

First, we formed two groups each comprising 11 Latinas. Two facilitators, a cofacilitator/observer, and a research assistant conducted a total of five sessions per group. During these sessions, participants were introduced to the project, key concepts, and components of the photovoice methodology: core values, agenda and project goals, introduction to the use of photovoice, techniques to capture images associated with lived experiences, and ethics and safety issues associated with taking and using photography. Each participant received a disposable camera to document and describe her unique lived experiences and perspectives on domestic violence. Participants later selected photographs and images for the group discussions. Group dialogue facilitated critical thinking, allowing participants to collectively uncover their skills and cope with their shared experiences of IPV. The two groups came together in the fifth session and chose to integrate their work into a single project gallery. Participants collaboratively selected the photographs, stories, and final themes for public presentation of the gallery. The director and curator of the University of Texas at El Paso Museum collaborated with project participants in order to create a layout and reproduce the photographs in a format appropriate for a gallery presentation. Project participants were responsible for the final approval of all photographs and stories presented in the public gallery. The project lasted 6 months from participant recruitment to dissemination of study findings. Photovoice training and facilitation of sessions lasted 5 months.

Both of the project facilitators are Latina women with knowledge of issues related to IPV. One is a psychologist with a doctoral degree and extensive experience working on issues of IPV and sexual and reproductive health among women in the U.S.–Mexico border. The other has a doctoral degree in interdisciplinary health sciences and is a licensed social worker with vast experience in sexuality education, U.S.–Mexico border health issues, and the photovoice methodology. There was a third cofacilitator/observer, a Latino graduate social work student with experience working with vulnerable populations. The women gathered once a week at two training sites (the community setting in San Elizario, Texa, a rural town outside of the City limits; and the University of Texas at El Paso campus, which is centrally located) for the group discussions. Each discussion was audio recorded for data analysis.

When participants encountered difficulties with the community sites, operating cameras, transportation to the training site, or were otherwise not able to attend the group discussion for any reason, researchers (facilitators) conducted a formative evaluation to address these needs. In addition, research staff received input and support from the advisory committee, comprising community stakeholders with knowledge and expertise on IPV and sexual and reproductive health issues.

Themes Selection

Project facilitators encouraged participants to take photos related to the following themes: (a) lived experiences as victims/survivors of IPV, (b) the impact of IPV on sexual and reproductive health, and (c) recommendations to address IPV and improve sexual and reproductive health. Participants self-selected the photos for discussion and were guided by the facilitators to provide thoughtful interpretation and analysis. We did not assume literacy among the project participants, and we purposely chose a camera for which the ability to read numbers was unnecessary.

Participatory Analysis Using Critical Reflection and Dialogue

As part of the unique methodological approach used in this study, the project's facilitators, research assistant/observer, advisory committee, and participants were all included in the process of data analysis. The researchers (experienced in qualitative methods) reviewed each of the photovoice group audio recordings to capture the major elements and themes. Participants engaged in a three-pronged process of participatory analysis: (a) selecting those photographs that most accurately reflected their realities and concerns, (b) contextualizing the photos through stories about what the photographs mean, and (c) codifying the issues and themes that emerged from their stories. This process was based on the concept of critical consciousness (Freire, 2000) as well as concepts from feminist theory (Wang & Burris, 1997).

Participants selected the photographs and defined the course of discussion. Each participant selected photographs (i.e., three to four per session) that they felt were most significant or liked best from each roll of film taken. The participants then contextualized their photos through group discussions. Women shared stories about their own photographs and defined the meaning of their images. Researchers and participants conducted their discussions in Spanish. Participants framed their stories in terms of questions spelling the acronym SHOWeD in English: What do you See here? (¿Qué ve usted aquí?); What is really Happening here? (¿Qué es lo que realmente está pasando?); How does this relate to Our lives? (¿Cómo se relaciona esto con nuestras vidas?); Why does this problem or strength Exist? (¿Porqué existe esta situación, problema o fortaleza?); What can we Do about it? (¿Qué podemos nosotros hacer al respecto?; Wallerstein & Bernstein, 1988). The PI (primary author) secured authorization from Nina Wallerstein (author of the SHOWeD method), to translate and adapt the SHOWeD acronym into Spanish. This set of questions helped the participants identify the problems and assets and critically discuss the determinants of their situation to ultimately develop recommendations and strategies for changing the situation.

Participants also wrote down personal anecdotes. All of the women had at least a fifth-grade education and were capable of speaking and writing in their native language, Spanish. Group observers (undergraduate fine arts student and a graduate social work student) documented the project activities and group process. The photographs and accompanying stories were displayed at each session, and researchers read the stories out aloud to participants. Participants voted on the stories and photographs that best represented their perspectives and then grouped the photographs into emerging themes. The final stage was codifying, a process rooted in the understanding that the participatory approach may generate multiple meanings from a single photograph. At this stage, participants identified multiple dimensions arising from the discussion process, including key issues and themes (Wang & Burris, 1997). Once all the thematic analysis sessions were complete, the researchers conducted a final analysis with participants in which the themes from the two groups were consolidated. The two groups came together as one to finalize themes, plan the exhibition event, and prepare a “Call to Action” to present to policy and decision makers.

Ethical Considerations

Several issues and challenges arise when conducting research with victims of IPV (Wagman, Francisco, Glass, Sharps, & Campbell, 2008). We developed protocols for facilitators that provided concrete guidelines to help clarify the ethical dilemmas that researchers frequently face when working with victims of IPV, including emotional distress and safety of the victims. Additionally, research staff was trained on the use of the personalized safety plan, which included discussions on general safety skills and strategies to use during a violent encounter. Fortunately, there were no reports of adverse events, including incidents of emotional distress or other safety concerns. Finally, written consent was obtained from all participants to share their photos and written anecdotes.

Results

Between March and July 2012, the 22 participants produced a total of 198 photographs and accompanying stories. The participants' ages ranged from 16 to 72 years. For a complete list of participant characteristics, see Table 1.

Each group of participants organized photographs and accompanying themes into categories. Two major themes emerged: “Expressions of Domestic Violence” and “Effects of IPV on Sexual and Reproductive Health.” Participants also came up with policy recommendations, which were coded as “Recommendations to Improve IPV and Sexual and Reproductive Health Services.”

Expressions of Domestic Violence

A wide range of domestic violence issues were identified, including stigma and discrimination from community and family members, loneliness and isolation, fear of dying and suicidal thoughts, financial and economic abuse, physical and emotional abuse, and sexual coercion. To protect participants' identity and confidentiality, we assigned them pseudonyms during the data-coding process.

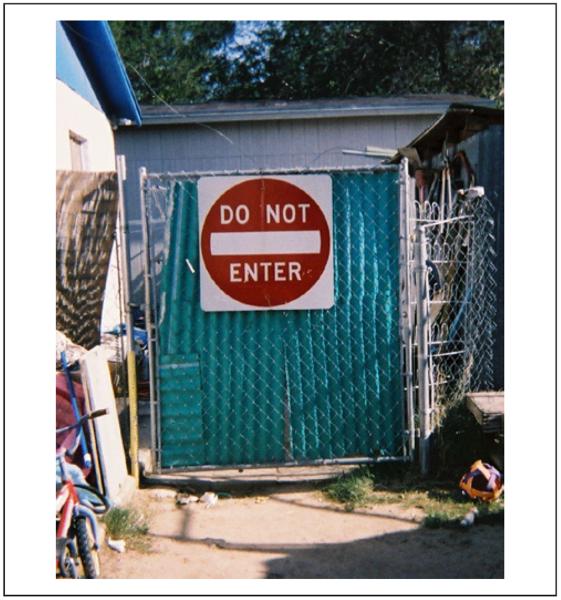

Some of the participants talked about denial, isolation, shame, fear, emotional violence, and discrimination and how these experiences affected their lives. Norma took the photo in Figure 1 and elaborated,

When you are part of an abusive relationship and a person tries to talk about it (violence), we immediately hang the “stop” sign. We isolate ourselves from everyone that tries to make us deal with the situation that we try to avoid. I lived this way for fear of being pointed at and discriminated against. To accept that we are victims is seen as something bad and shameful within our families and society. (Photograph and story by Norma, 40, translated from Spanish)

FIGURE 1. Stop.

NOTE: “When you are part of an abusive relationship and a person tries to talk about it (violence), we immediately hang up the `stop' sign. We isolate ourselves from everyone that tries to make us deal with the situation that we try to avoid. I lived this way for fear of being pointed at and discriminated. To accept that we are victims is seen as something bad and shameful within our families and society” (Norma, 40).

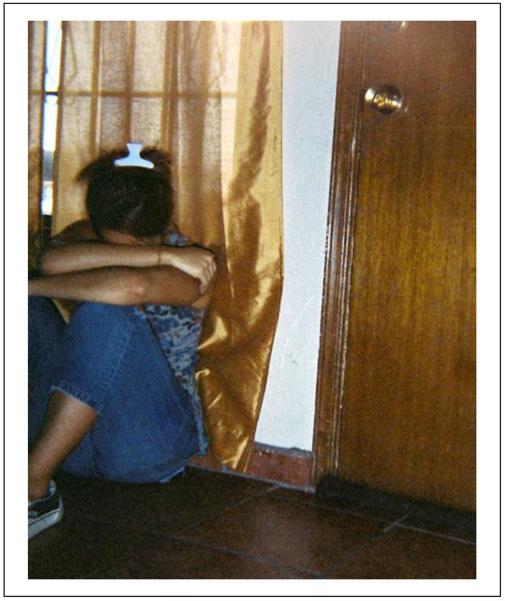

Many participants reflected on their feelings of hopelessness, humiliation, loneliness, fear, and isolation from resources and services due to physical, sexual, and verbal abuse. Figure 2, which consists of a staged photograph used for the purpose of the project, captures Maria's concern:

She [another group participant], I, just like you, suffered physical, mental, and sexual violence. I was scared to face reality due to fear, shame, and ignorance; I put up with blows, humiliations and offensive comments for a long time. I was scared of speaking out and asking for help. Little by little I was sinking into a dark hole. I said “Enough!” I had the courage to stop the domestic violence, raise my voice, and ask for help. Today, I live free, relaxed, and ready to move on. Now I tell you. Just like me, give yourself the courage to decide and say, “Enough.” (Photograph and story by Maria, 43, translated from Spanish)

FIGURE 2. I, Like You.

NOTE: “I, just like you, suffered physical, mental and sexual violence. I was scared to face reality due to fear, shame and ignorance. I put up with blows, humiliations and offensive comments for a long time. I was scared of speaking out and asking for help. Little by little I was sinking into a dark hole. I said “Enough!” I had the courage to stop the domestic violence, raise my voice, and ask for help. Today, I live free, relaxed, and ready to move on. Now I tell you. Just like me, give yourself the courage to decide and say enough” (Maria, 43).

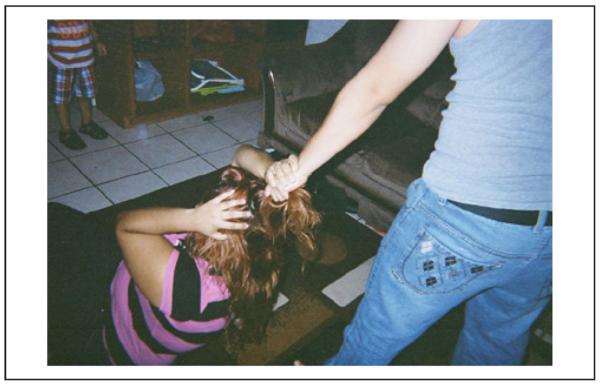

Other participants talked about the fear of death and other mental health issues as a result of domestic violence. Imelda took the photo in Figure 3 and explained,

She was afraid of dying when she suffered through emotional and physical abuse. She got a feeling of desperation and loneliness as a result of her immigration status (undocumented) and from not having any family nearby. She has fought on her own to take care of her daughters, even though she has had a partner for four years, and he is her daughter's stepfather. Her husband, an American (U.S.) citizen, sometimes gets home late and drunk. He torments and tells her that he won't “give her the immigration papers.” She went into depression, and when she heard the train passing by her house, occasionally thought about suicide. She has no support from any family member. However, having a career and the love for her daughters has made her stronger to keep going. She keeps quiet for fear of getting deported or separated from her daughters. We allow the abuse, more so if we are undocumented. Raise your voice. Share your experiences. Report the aggressor. Look for help. You are not alone. You have rights. Use the resources. (Imelda, 35, translated from Spanish)

FIGURE 3. Desperation and Desolation.

NOTE: “She was afraid of dying when she suffered through emotional and physical abuse. She got a feeling of desperation and loneliness as a result of her immigration status and from not having any family nearby. She has fought on her own to take care of her daughters, even though she has had a partner for four years but he is her daughter's stepfather. Her husband, an American citizen, sometimes gets home late and drunk. He torments her and tells her that he won't “give her the immigration papers.” She fell into depression, and when she heard the train passing by her house, she would occasionally think about suicide. She has no support from any family member. However, having a career and the love for her daughters has made her strong enough to keep going. They keep quiet for fear of getting deported or separated from her daughters. We allow the abuse, more so if we are undocumented. Raise your voice. Share your experiences. Report the aggressor. Look for help. You are not alone. You have rights, use the resources” (Imelda, 35).

Although most of the participants were not aware of the legal resources available for battered women, some were aware of these resources and expressed their willingness to seek legal assistance (i.e., protective order, Violence Against Women Act, U-Visa) and denounce violence. Maria explained,

Physical and emotional abuse affects everything in our lives. In my sister, [abuse] affected her nerves. She now has facial paralysis. We need to help women so that they recognize when they're being abused so they can escape and not allow humiliation. Leaving the fear behind, reporting the aggressor, seeking shelter and protection is vital. The Violence Against Women Act grants protection to women so they can get on with their life. Without economic independence they may not have enough money and may end up in the streets. I also lived with domestic violence. (Maria, 41, translated from Spanish)

Sexual and Reproductive Health

All of our participants talked about how IPV affected their physical and mental health, reduced their sexual autonomy, and increased the risk of HIV and STIs. All of the women felt that the risk of sexual assault affected their quality of life and impaired their daily activities. A common theme that emerged from the qualitative data was sexual assault and coercion from the perpetrator. Berenice explained,

Covering the negligee with the hands and saying, “No more,” being forced to have sexual intercourse, without feeling respected or loved, learning to say no. All of this because we are being subjected to the rules of our generation, culture or husband (or partner), we don't exercise the right to have or not to have intercourse. How far does our sensuality go and where does the line of abuse start? Let's learn to say when and how we want to have sexual intercourse. (Berenice, 34, translated from Spanish)

Lulu added:

I felt like dirty water after being forced to have sex: dirty, used, and worthless. I thought it was my duty to have sexual intercourse with my husband even if I didn't want to. When he wanted to have intercourse, instead of telling me that he wanted me, he said I want to “use you,” and that made me feel like a disposable object. This made me feel humiliated and subdued. As women we must not allow them (men) to degrade us and see us as objects. There should be respect and understanding in a relationship. (Lulu, 47, translated from Spanish)

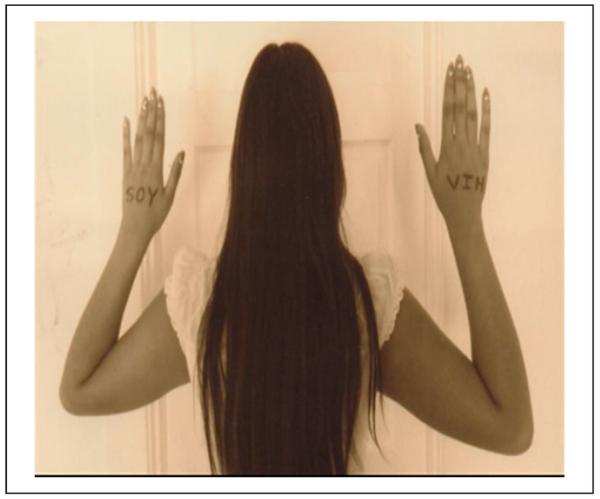

Most participants reported STIs from their partners and were afraid to seek medical care because of their status. Elsa's emotions are captured in Figure 4 and underscored the urgent need to increase education and resources regarding HIV and STIs:

Many women aren't happy and live with fear and they're afraid to say they have a sexually transmitted disease such as HIV/AIDS for the risk of being stigmatized or discriminated against. We need more education to stop the stigma and discrimination of people with HIV/AIDS or any another STD. (Elsa, 37, translated from Spanish)

FIGURE 4. Shame.

NOTE: “Many women aren't happy, they live with fear and are afraid to say they have a sexually transmitted disease such as HIV/AIDS for the risk of being pointed at or discriminated. We need more education to stop the discrimination against other people.” (Elsa, 37).

A salient theme was the socialization of women in Mexican culture as the primary caretakers of their families. Mexican cultural standards prescribe women the role of caring for the needs of their spouse (or partner), children, family, and the household, and this domestic role is of utmost importance. Berenice's story is an illustration of how these behaviors, attitudes, and practices are embedded in cultural norms. Using metaphors and symbols like cooking appliances, mechanic tools, a menstrual cycle calendar, and birth control pills, Berenice describes her own understanding of the importance of self-care:

We are all familiar with the first four tools (two mechanic and two kitchen appliances), but not as familiar with the last two (birth control pills and menstrual flow chart). As women we assume we have to take care of others (family), fix things or situations, but we rarely take care of ourselves. If I ask myself: “When did I do my last mammogram? When did I get a gynecological exam? What did I recently teach my daughter about her self-care?” We must raise our self-esteem and accept ourselves as valuable and important. In our home and in our personal life we need greater awareness of the right tools for personal care. (Berenice, 34, translated from Spanish)

Recommendations From Participants

Participants discussed and proposed a “Call to Action” that included several items to help prevent and address IPV and improve sexual and reproductive health. These included increasing the visibility of people affected by domestic violence, working for equality, raising awareness, increasing prevention services, identifying strategies to reach affected victims and aggressors, allocating funding and resources for domestic violence, and increasing the quality of and access to sexual and reproductive health. A list of these action items can be found in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Recommendations From Participants

| Call to Action to Improve Women's Health |

|---|

| 1. Increase the visibility of people affected by violence through promoting their stories, lived experiences, hopes, and aspirations. |

| 2. Equality will be achieved when violence and threats are eliminated from battered women's lives. |

| 3. Raise awareness about violence against women and promote sexual and reproductive health. Advocate for the reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act and U-Visa Program. |

| 4. Include prevention and attention to violence in every work setting to increase the level of knowledge about the effect of domestic violence on women, their health, and their family, including children and aggressors. |

| 5. Establish strategies to increase services and reach battered women and aggressors. |

| 6. Increase funding for services and interventions for women, girls, and aggressors. |

| 7. Provide quality access to sexual and reproductive health. |

| 8. Promote education as an empowerment tool for women. |

Action Items Identified by Community Stakeholders

The study's investigators recruited 20 members for the advisory committee to serve as influential policy and decision makers. The advisory committee members provided a productive and safe setting for the women to present their perspectives and problems for which they sought action. Members also identified audiences and venues for the women to present their photo gallery and the “Call to Action.” As a result of the partnership, the women presented their gallery and concerns at local conferences, academic settings, community forums, and the Mexican Consulate's office in El Paso. The project investigators organized these presentations and several community projects have been initiated as a result of this partnership. The first exhibit consisted of 34 panels and was presented by participants at the University Museum during the official closure of the XII Binational Health Week. Federal, state, and local health authorities from Mexico and the United States attended the event, providing an opportunity for study participants to present their “Call to Action” and encourage key health officials to make a public commitment to address IPV and sexual and reproductive health. Additionally, the project gallery traveled to more than 15 local, states, national and international forums, allowing participants to present their work at both local and statewide events. In addition, the cofacilitator and graduate student produced a bilingual 12-minute interactive documentary titled “Voices and Images of Migrant Women, Domestic Violence, Sexual and Reproductive Health” based on project participants perspectives on IPV and the photo-voice project experiences. A summary of these action items and projects initiated can be found in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Action Items Identified by Stakeholders and Projects Initiated

| Action Items | Projects Initiated |

|---|---|

| • 15 bilingual Photovoice gallery presentations | • Monthly follow-up meetings with project participants and community partners |

| • Presentation of “Call to Action,” an event open to the public where women presented their photos and advocated for social justice and policy action | • Successfully submitted, acquired, and completed a promotora (community health worker) training project |

| • Increase local, national, and binational media coverage of the impact of IPV on Latinas in the U.S.-Mexico border region | • The establishment of a system to connect and refer participants to health, legal aid agencies, human services, and educational programs |

| • Promote through policy reports, presentations at local, state, national, and international conferences and advocacy memorandums the reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act and U-Visa program | • A dissemination strategy to promote IPV prevention programs in Mexico |

NOTE: IPV = intimate partner violence.

DISCUSSION

Our study used evidence-based data to demonstrate that IPV is a major public health issue affecting Latinas in the border region. Our findings have salient implications for women's reproductive, sexual, and mental health outcomes and resonate with the limited research on IPV that has found that intersecting factors of gender, violence, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and legal status expose Latinas to multiple vulnerabilities and negative health effects. For Latinas, it appears that income (Cunradi, Caetano, Clark, & Schafer, 2000), education (Denham et al., 2007), and employment (Cunradi et al., 2000) may be associated with IPV. In addition, isolation, fear of deportation, lack of family support, and limited access to social services perpetuate IPV and prevent women from seeking protective and support services (Adams & Campbell, 2012; Fuchsel, Murphy, & Dufresne, 2012; Moynihan et al., 2008; Raj & Silverman, 2002). However, given the socioeconomic disadvantages faced by Latinos in the United States, it is essential to obtain a deeper understanding of these variables and how they relate to IPV.

Study participants identified several barriers to sexual and reproductive health: limited (or no) access to health, legal, and social services (including the use of immigration status by their intimate partner as a form of manipulation); fear of deportation and separation from children; limited English proficiency; and the lack of health insurance. In our study, only three participants had health insurance (two have Medicaid and one has private insurance). The inability to access physical and mental health services interfered with their ability to prevent, screen, and address IPV and adequately fulfill sexual and reproductive health needs. In particular, the state legislature in Texas has cut reproductive health care funding, causing the shutdown of numerous family-planning clinics in low-income communities. Latinas and African American communities have been some of the hardest hit by these funding cuts, since they typically reside in low-income areas. In addition, lack of sensitivity by family members and police officers discouraged some of the participants from seeking protective orders and emergency shelters for their children and themselves. The long-term effects of such legislative policies remain unknown, and more health policy research is needed to further understand this particular issue.

Participants discussed the importance of legislation (e.g., Violence Against Women Act and U-Visas) and mandates at the local, state, and national levels and indicated that few initiatives are in place to integrate a response to IPV into reproductive and sexual health services. Pragmatic responses and feasible solutions can address these widespread concerns. Even relatively low-resource initiatives can make a difference by ensuring that Latinas' experiences are validated and that they are not judged or blamed for the violence they report. A consensus emerged among the study participants: the use of promotoras (community health worker) to better reach and address IPV and sexual and reproductive health concerns in the U.S.–Mexico border region and beyond. The community health worker or promotora model can be used to disseminate information on IPV and connect affected women to resources, including legal aid and sexual and reproductive health agencies. Promotoras act as the bridge between governmental and nongovernmental systems and the communities they serve (World Health Organization, 2007).

In settings with more resources, participants identified the need to train service providers and other public health authorities to better understand the prevalence of IPV among women as well as the importance of prevention, service provision, and screening for them and their children. Participants identified the need for culturally and linguistically competent prevention and intervention programs as essential to addressing IPV. In addition, they pointed to a need to develop tools and skills that will help vulnerable Latinas navigate the complex health, social, legal, and educational systems they encounter.

Some study limitations are worth mentioning. As previously stated, the participants consisted of a convenience sample of Latinas in El Paso, Texas; thus, causation must be taken into consideration when generalizing the results to other groups. More research is needed to advance a more comprehensive understanding of the state of IPV and sexual and reproductive health for Latinas. In particular, longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the prevalence of IPV among Latinas over time. In addition, our study was limited to Mexican-origin migrant women who have experienced IPV. Future research could expand to include a more diverse group of women to better understand the challenges of a representative sample of the many groups of immigrant women living in the U.S.–Mexico border region, including Central American women who might have experienced violence crossing several borders on their journey to the United States. Furthermore, data are needed to document the unique health challenges associated with IPV affecting male-to-female transgender Latinas in the border region.

Despite its limitations, the findings from this study have several important implications for research, practice, and policy. The high prevalence of IPV and lack of sexual and reproductive health services within this population underscore the need to conduct more research about the risk factors, consequences of IPV, and sexual and reproductive health needs in the Latina community. Researchers need to develop more innovative and creative ways to address the various socioeconomic, environmental, linguistic, and cultural barriers that have traditionally kept Latinas from participating in research.

Implications for Practice and Policy

The effect of IPV on mental, sexual, and reproductive health is real and has important health implications for Latinas. Service providers, clinicians, and decision makers working with Latinas need to be acutely aware of IPV and sexual and reproductive health conditions prevalent among this population. Being knowledgeable about the prevalence of IPV in this population will support ongoing screenings for signs and symptoms of IPV during routine health and human service visits.

The qualitative data gathered from the photovoice group discussions were supplemented with photos and images, which revealed the broader context of sexual health in the lived experiences of women who have experienced IPV. During group discussions, participants identified barriers to health services and explained the ways that structural barriers at the policy, cultural, and institutional levels trickle down to the community and individual to block access to services for battered women. Photovoice group discussion participants also described how structural barriers like stigma, discrimination, humiliation, oppression, economic control, and fear have forced victims of IPV to hide their struggles and health concerns from family members, employers, health providers, and policy officers. Therefore, new strategies are needed to better reach and serve the concerns of this particular population.

Interventions must both disrupt the negative effects of barriers and bolster the protective factors of Latinas. Study participants clearly indicated that community engagement and community-based organizations are central to moderating barriers and promoting access to IPV, sexual, and reproductive health services. Successfully addressing sexual and reproductive health among victims of IPV will require a real effort to address structural barriers. Activities must be addressed that aim to increase Latinas' protective factors and positive perception of themselves and to reduce relationship stressors that may relate to income, education, and immigration status.

Addressing structural barriers remains essential to realizing the potential of comprehensive health promotion interventions and programs for victims of IPV. Investments in the development of health and mental health service professionals and workers and new interventions and programs must be accompanied by efforts to increase access to IPV prevention and services. Policies to increase Latina women's access to health care (e.g., the Affordable Health Care Act 2010, Medicaid expansion, increased resources of community health centers, and community-based organizations providing care to vulnerable and underserved populations) could help more women access the health services that they so urgently need.

As a result of this project, we trained 20 promotoras in the U.S.–Mexico border region on IPV issues. These issues included the effect of IPV on reproductive and sexual health (including the transmission of HIV and other STIs), and the need to channel IPV resources into vulnerable communities. Promotoras received a 180-hour training that equipped them with fundamental IPV knowledge, advocacy and leadership skills. On completion of the training program, promotoras conducted further outreach in their communities and their social networks to share their knowledge with friends, family, and neighbors through various activities including group presentations, one-on-one outreach, and community health fairs. Our ultimate goal is to educate and empower Latinas and immigrants in order to reduce the incidence of IPV, improve access to sexual and reproductive health services, and work toward the ultimate goal of social justice.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of the photovoice project for their sharing their experiences, insight, and strengths. We appreciate the help of the students and volunteers. We are grateful to the members of the Advisory Committee and partner organizations for their advice and support, and the University of Texas at El Paso Centennial Museum, the College of Health Sciences, and the Department of Language and Linguistics of the University of Texas at El Paso. Omar Martinez is supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (Behavioral Research in HIV Infection; T32 MH19139 Behavioral Sciences Research in HIV infection; PI: Theo Sandfort, PhD). Funding for this study was provided by the College of Health Sciences CAP2 grant (PI: Eva Moya, PhD). This study received institutional review board approval from the University of Texas at El Paso (336186-1) on June 4, 2012.

REFERENCES

- Abbott J. Injuries and illnesses of domestic violence. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1997;29:781–785. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70200-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams ME, Campbell J. Being undocumented & intimate partner violence (IPV): Multiple vulnerabilities through the lens of feminist intersectionality. Women's Health & Urban Life. 2012;11:15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence in eighteen U.S. states/ territories, 2005. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalani C, Minkler M. Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education & Behavior. 2010;37:424–451. doi: 10.1177/1090198109342084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Kim W. Intimate partner violence among Asian Americans and their use of mental health services: Comparisons with White, Black, and Latino victims. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health. 2012;14:809–815. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9625-3. doi:10.1007/s10903-012-9625-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall M, Schwab J, Sheehan K, Esposito T. Illinois trauma centers and intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:2096–2108. doi: 10.1177/0886260508327702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Clark C, Schafer J. Neighborhood poverty as a predictor of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States: A multilevel analysis. Annals of Epidemiology. 2000;10:297–308. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham AC, Frasier PY, Hooten EG, Belton L, Newton W, Gonzalez P, Campbell MK. Intimate partner violence among Latinas in eastern North Carolina. Violence Against Women. 2007;13:123–140. doi: 10.1177/1077801206296983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deusdad-Ayala B, Moya E, Chavez-Baray SM. Domestic violence against migrant women at the border: The case study of El Paso, Texas. Spanish Journal Social Work. 2012;12:13–21. doi:10.5218/prts.2012.0002. [Google Scholar]

- Fedovskiy K, Higgins S, Paranjape A. Intimate partner violence: How does it impact major depressive disorder and post traumatic stress disorder among immigrant Latinas? Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health. 2008;10:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. 30th Anniversary ed. Bloomsbury Academic; London, England: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchsel CLM, Murphy SB, Dufresne R. Domestic violence, culture, and relationship dynamics among immigrant Mexican women. Affilia: Journal of Women & Social Work. 2012;27:263–274. doi:10.1177/0886109912452403. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia CM, Aguilera-Guzman RM, Lindgren S, Gutierrez R, Raniolo B, Genis T, Clausen L. Intergenerational photovoice projects: Optimizing this mechanism for influencing health promotion policies and strengthening relationships. Health Promotion Practice. 2013;14:695–705. doi: 10.1177/1524839912463575. doi:10.1177/1524839912463575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert L, El-Bassel N, Chang M, Wu E, Roy L. Substance use and partner violence among urban women seeking emergency care. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:226–235. doi: 10.1037/a0025869. doi:10.1037/a0025869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14:99–132. [Google Scholar]

- González-Guarda RM, Peragallo N, Vasquez EP, Urrutia MT, Mitrani VB. Intimate partner violence, depression, and resource availability among a community sample of Hispanic women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2009;30:227–236. doi: 10.1080/01612840802701109. doi:10.1080/01612840802701109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Guarda RM, Vasquez EP, Urrutia MT, Villarruel AM, Peragallo N. Hispanic women's experiences with substance abuse, intimate partner violence, and risk for HIV. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2011;22:46–54. doi: 10.1177/1043659610387079. doi:10.1177/1043659610387079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guruge S, Humphreys J. Barriers affecting access to and use of formal social supports among abused immigrant women. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 2009;41(3):64–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottemoeller M. Ending violence against women (Population Reports, Series L, No. 11) Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health; Baltimore, MD: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kishor S. Married women's risk of STIs in developing countries: The role of intimate partner violence and partner's infection status. Violence Against Women. 2012;18:829–853. doi: 10.1177/1077801212455358. doi:10.1177/1077801212455358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusk M, Staudt K, Moya E. Social justice in the U.S.- Mexico border region. Springer; New York, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Campbell J, Sweat MD, Gielen AC. The intersections of HIV and violence: Directions for future research and interventions. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50:459–478. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarraher DR, Martin SL, Bailey PE. The influence of method-related partner violence on covert pill use and pill discontinuation among women living in La Paz, El Alto and Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2006;38:169–186. doi: 10.1017/S0021932005025897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire WJ. Attitudes and attitude change. In: Lindzey G, Aronson E, editors. Handbook of social psychology. Vol. 2. Random House; New York, NY: 1985. pp. 233–346. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza G, Ruiz A, Escárzaga EF, Ford R. Diagnostic of Healthcare Services: Vol. 2. United States-Mexico border: United States. Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization, United States-Mexico Border Field Office; El Paso, TX: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan B, Gaboury MT, Onken KJ. Undocumented and unprotected immigrant women and children in harm's way. Journal of Forensic Nursing. 2008;4:123–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-3938.2008.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control . The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Newswire PR. Texas gains the most in population since the census: First population estimates since 2010 show slowest national growth since the 1940s. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb11-215.html.

- Rahman M, Nakamura K, Seino K, Kizuki M. Intimate partner violence and use of reproductive health services among married women: Evidence from a national Bangladeshi sample. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:913. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-913. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Silverman J. Violence against immigrant women: The roles of culture, context, and legal immigrant status on intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:367–398. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha NA, Mata AG, Jr., Tyroch AH, McLean S, Blough L. Trauma registries as a potential source for family violence and other cases of intimate partner violence for border communities: Indicator data trends from 2000–2002. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology. 2006;34:87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MA, Heilemann MV, Fielder E, Ang A, Nevarez F, Mangione CM. Intimate partner violence, depression, and PTSD among pregnant Latina women. Annals of Family Medicine. 2008;6:44–52. doi: 10.1370/afm.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar NN. The impact of intimate partner violence on women's reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2008;28:266–271. doi: 10.1080/01443610802042415. doi:10.1080/014436 10802042415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer KR, Brant J, Gupta S, Thorpe J, Winstead-Derlega C, Pinkerton R, Dillingham R. Intimate partner violence: A predictor of worse HIV outcomes and engagement in care. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2012;26:356–365. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0409. doi:10.1089/apc.2011.0409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P. Prevalence and consequences of male-to-female and female-to-male intimate partner. Violence Against Women. 2000;6:142–161. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JM, Rodriguez MA, Lapeyrouse LM, Muyu Z. Recent intimate partner violence as a prenatal predictor of maternal depression in the first year postpartum among Latinas. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2011;14:135–143. doi: 10.1007/s00737-010-0191-1. doi:10.1007/s00737-010-0191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalobos G, Islas AA. Mental health disparities and social justice in the US-Mexico border region. In: Lusk M, Staudt K, Moya E, editors. Social justice in the U.S.-Mexico border region. Springer; Dordrecht, Netherlands: 2012. pp. 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- Wagman J, Francisco L, Glass N, Sharps PW, Campbell JC. Ethical challenges of research on and care for victims of intimate partner violence. Journal of Clinical Ethics. 2008;19:371–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Empowerment education: Freire's ideas adapted to health education. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15:379–394. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior. 1997;24:369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Community health workers: What do we know about them? The state of evidence on programmes, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes of using community health workers. Author; Geneva, Switzerland: 2007. [Google Scholar]